« Prev Next »

"Some scientists may dismiss this matter forthwith, on the ground that ecology has no relation to right and wrong. To such I reply that science, if not philosophy, should by now have made us cautious about dismissals." — Aldo Leopold (1933, emphasis added).

The dogma that science and ethics belong to separate universes of discourse, nor ever the twain should have permissible intercourse and legitimate issue, was a foundational pillar of twentieth-century philosophy. Facts and values, ethics and science, ises and oughts belong to hermetically sealed compartments of thought and speech. Thus the very idea that ecology has an ethical perspective conjures up the specter of the "Is-Ought Dichotomy": the derivation of oughts from ises, values from facts, ethics from science. Now, however, the twentieth-century is over and philosophy's once adamantine pillars of "wisdom" are — one by one — turning to dust and blowing away. The sciences and the facts they disclose do inform our values and transform our ethics — and well they should. The scientific fact, for example, that Homo sapiens is a single species, originating in Africa and, from there, spreading all across the planet, makes belief in the superiority of a single human "race" untenable. Indeed racism is based on the false belief that race is a biological taxon analogous to species, but we know now — thanks to the human genome project, thanks to science — that it is not. We properly correct false values — racism, misogyny, homophobia, xenophobia — by appeal to the facts disclosed by science all the time.

What false values might be corrected by appeal to ecology? As any textbook in ecology will note, ecology is the study of the distribution and abundance of living organisms and the relationships of organisms with their environments, which include other organisms as well as inanimate factors such as soil, water, and air. Human manipulations of natural environments almost always entrain unanticipated and very often unwelcome consequences — the "side effects" of our actions as we wistfully call them. Under the sway of pre-ecological scientific reductionism and atomism, we once conceived the natural environment to consist of an inanimate surface on which plants and animals were arrayed rather like furniture on the floor of a big room. If we were unhappy with the way the living furniture of the Earth was arranged, we could rearrange it, better to our liking, by removing some species (bison, prairie flora, wolves) and importing others (cattle, wheat, horses). More technically put, we conceived of organisms as "externally related" to one another and to their inanimate environments. Evolutionary ecology conceives of organisms as "internally related" to one another and to their inanimate environments, through mutual adaptation. Ecosystems may not be as tightly integrated as ecologists once supposed, but few ecologists would assert that organisms independently adapted to similar environmental gradients are completely independent of all the others. Therefore, human manipulations of natural environments can have catastrophic side effects, which ultimately can grievously harm us humans in a variety of ways. Overgrazing domestic stock can cause soil erosion and even desertification and thus diminish food production; introduced organisms can become crop pests or carry some of the diseases that afflict us; the extinction of species can deprive us of potential resources, especially medicines. Thus ecology warrants what some philosophers have called a "hermeneutic of suspicion" when someone proposes significantly to manipulate the environment for some alleged benefit. In the current Age of Ecology we require at least a benefit-cost analysis of any such proposal and often an environmental impact statement before we allow it cautiously to proceed. Even if we assume a narrow anthropocentrism — that only human interests count morally — ecology has clear ethical implications.

Ecology is not only a science, it is also a worldview. Through the lens of ecology, we now view the components of the natural environment as internally related, whereas before the advent of ecology, we viewed the components of the natural environment as externally related. Ecology grew out of evolutionary biology and so viewing the environment through its lens also brings into focus an evolutionary as well as ecological ethical perspective. Not only does ecology inform our conception of the natural environment it reforms our conception of who we are as human beings. That, in turn, entails a reformed conception of the proper human relationship with the natural environment. Both the religious and philosophical legacies of Western civilization portrayed human beings as set apart from the rest of nature and licensed to treat the environment as a pool of "natural resources," valuable only to the extent that it satisfies vaunted human desires or preferences — whether impulsive desires or considered preferences. In other words, we have inherited a two-and-half millennium tradition of narrow anthropocentrism from Western civilization. From an evolutionary point of view, however, Homo sapiens, is, like all others, an evolved species. Certainly we have evolved some very special and unique abilities, but do they entitle us to consider ourselves as uniquely privileged in comparison with all other species? The evolutionary-ecological worldview is humbling. It is also inspiring: we discover ourselves to be the scions of a biological ancestry going back in time some three and a half billion years. We can look back on our evolutionary family tree with wonder, awe, and pride in our parentage. And we can look with sympathy and compassion on our living "fellow-voyagers" in the "odyssey of evolution" and experience "a sense of kinship" with them — our companions on this incredible journey (Leopold 1949). So seen, we begin to value them intrinsically as well as instrumentally — no longer, that is, as mere means to our selfish human ends and purposes.

How can we fruitfully portray the way organisms and their environments are "internally related?" Several conceptual "paradigms" have dominated ecology in its more than century-old history as a science. Plants and animals were sometimes conceived to be related to one another as working parts of a machine. Thus, in the spirit of the first of the ethical implications of ecology reviewed here, Aldo Leopold (1953) famously wrote, "If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. . . . To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering." By other ecologists, plants and animals were conceived to be related to one another as cells in super-sized organisms and the species, of which they were specimens, to function as organs in super-sized organisms (Clements 1905). Such an organismic conception of the natural environment would suggest an even stricter application of the so-called "precautionary principle," to which Leopold alludes — because tinkering with highly integrated organisms is even riskier than tinkering with complex machines.

Another perennial paradigm in ecology conceives the internal relationships among plants and animals with one another and with their inanimate environments as like the internal relationships of the members of a human community or society with one another and with the community as a whole. In human communities or societies, individuals perform specialized roles, trades, or professions. They are doctors and lawyers and butchers and bakers and candlestick makers; they are farmers and factory workers and college professors and caterers; they are bus boys and bus drivers and preachers and politicians. These specialized roles or professions are internally related because one cannot be a college professor unless there are colleges and college students, nor can one be a lawyer unless there are laws crafted by politicians. In the economy of nature, as in the human economy, plants and animals also divide themselves into various specialized "roles" or professions. The three great guilds in the economy of nature are the producers, the consumers, and the decomposers. The producers are the green plants, the "autotrophs," that use solar radiation to assemble themselves from atmospheric carbon dioxide, water, and "nutrients" (various mineral elements that they find in the soils in which they root themselves, such as phosphorous, potassium, iron, and calcium). The consumers are the herbivorous animals that feed directly on plants, the omnivorous animals that eat both plants and other animals, the carnivorous animals that eat the omnivores and smaller carnivores, and the large carnivores at the top of the "food chain." The decomposers eat the dead bodies of plants and animals and reduce them to the elemental nutrients from which the plants compose themselves, thus completing a cycle, which goes on and on — slowing changing (evolving) as it goes — year after year, decade after decade, century after century, millennium after millennium.

Here we need to interject an important caveat. Biotic communities, no less than the human communities to which they are compared, are composed of relatively autonomous members and are dynamic, not just in evolutionary terms, but also in many other ways (Pickett and Ostfeld 1995). The autonomous members of biotic communities, just as do the autonomous members of human communities, come and go for various reasons — including opportunity to make a living (or the lack thereof), competitive advantage (or disadvantage), violent disturbance (or shelter from such), or just random shuffling and wander lust. Biotic communities, like the human communities to which they are compared, do not exist as static units nor do they move around as units (McIntosh 1975).

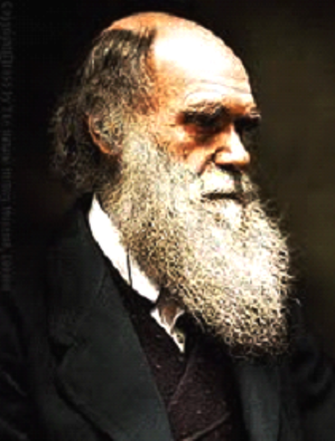

We human beings are, as the community analogy suggests, simultaneously members both of various human communities and economies and also of various "biotic communities" and the global "economy of nature." Thanks to Charles Darwin himself, followed today by a whole host of evolutionary psychologists, we now know that human ethics evolved by natural selection as a means to the end of social integration. As Darwin (1874) colorfully put it, "No tribe could hold together if murder, robbery, treachery, etc., were common; consequently such crimes within the limits of the same tribe ‘are branded with everlasting infamy'" — that is, such behaviors are declared to be "crimes," to be immoral, unethical, anti-social (tellingly), wicked, bad, evil (Darwin, C. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, Second Edition. London: John Murray, 1874). Absent ethics, human communities could not hold together. But individual human survival depends on being a member of a well-integrated cooperative community. In our evolutionary past, to be a solitary human being was to be a dead human being — and a barren human being without offspring. To the end of holding together the communities enabling us to survive, flourish, and reproduce did our ethics get naturally selected.

Darwin goes on immediately to note that "such crimes" (murder, robbery treachery, etc.) that are branded with everlasting infamy "excite no such sentiment beyond these limits" — that is, the perceived boundaries of the tribe. As time has gone on, the limits of our human tribes have been expanded to nation states and now to the global village. Aldo Leopold attempted to push the boundaries of our sense of tribal or community membership further still, to the biotic community. Ecology, he wrote, "simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land"; an ecological ethic, Leopold (1949) concludes, "changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land — community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow members and also respect for the community as such." (Leopold, A. Sand County).

How then can we foster the ethical perspective of ecology? We first cultivate universal evolutionary-ecological literacy. We work to transform our global village from a collection of fractious neighborhoods enthralled by mutually contradictory primitive mythologies inherited from long-dead demagogues who lived in the darkness of ignorance many centuries before science shed light on who we are, whence we came, and where we live. The dissemination of evolutionary-ecological literacy and the ethical implications of the evolutionary-ecological worldview is the principal task of the present generation of ecological ethicists. Translating knowledge into policy and practice will be the principal task of the next.

Glossary

Ethics: A values-based system of constraints on individual behavior enabling social cooperation necessary for human flourishing

Dogma: A strongly held belief that is intractable to both logical and evidential criticism.

Universe of discourse: The shared language and meaning among members of a specialized community, such as scientists, philosophers, sportsmen, gamers, etc.

Value (verb transitive): The capacity to project onto various things and actions a range of subjectively originating characteristics or properties — such as good and bad, right and wrong, noble and ignoble, beauty and ugliness — in response to the objective characteristics or properties of those things and actions.

Value (noun): Subjectively originating characteristics or properties — such as good and bad, right and wrong, beauty and ugliness — as are projected onto various things and actions in response to the objective characteristics or properties of those things and actions.

Impulsive desires: Various things and actions that are spontaneously and uncritically desired.

Considered preferences: Various things, actions, or policies that are more desired than others after critical examination and reflection.

Reductionism: The belief that wholes are precisely equal to the sum of their parts in contrast to holism, the belief that wholes are greater than the sum of their parts.

Atomism: The belief that wholes are composed of smallest individual parts.

External relations: Relations among objects that do not affect the identity of the related objects, such as object A is to the right of object B.

Internal relations: Relations among objects that partially constitute the identities of the related objects, such as person A is the twin of person B.

Hermeneutic: A critical method of examining and interpreting various claims and beliefs.

Benefit-cost analysis: An economic exercise in which the benefits and costs of various alternative courses of action, policies, or regulations are expressed in a monetary metric and compared.

Odyssey: A wandering voyage with no predetermined destination.

Precautionary principle: Assigns the burden of proof that a new product or proposed project's benefits will greatly exceed its costs (including costs to human and environmental health) on the costs side of the benefit-cost analysis, such that the risk that costs will not approach or exceed the benefits must be ascertained to be negligible.

References and Recommended Reading

Bonner, J. T. Why Size Matters: From Bacteria to Blue Whales. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (2006).

Calder, W. A. Size, Function and Life History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (1984).

Bond, W. J. & van Wilgen, B. W. Fire and Plants. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall, 1996.

Cheverud, J. M. Relationships among ontogenetic, static, and evolutionary allometry. American Journal of Physiological Anthropology 59, 139-49 (1970).

Bond, W. J. & Keeley. J. E. Fire as a global ‘herbivore': the ecology and evolution of flammable ecosystems. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 20, 387-394 (2005).

Bowman, D. M. J. S., Balch, J. K. et al. Fire in the Earth system. Science 324, 481-484 (2009).

Trivers, R. L. Parental investment and sexual selection. In Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man 1871-1971. ed. Campbell, B. (London: Heinemann 1972), 136-179.

Parker, G. Sexual selection and sexual conflict. In Sexual Selection and Reproductive Competition in Insects. eds. Blum, M. S. & Blum, N. A. (New York: Academic Press, 1979), 123-166.

Clements, F. E. Research Methods in Ecology. Lincoln, NE: University Publishing Company (1905).

Darwin, C. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, Second Edition. London: John Murray (1874).

Leopold, A. The conservation ethic. Journal of Forestry 31, 634-643 (1933).

Leopold, A. A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There. New York: Oxford University Press (1949).

Leopold, A. Round River: From the Journals of Aldo Leopold. New York: Oxford University Press (1953).

McIntosh, R. P. H. A. Gleason, "individualistic ecologist," 1882-1975. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 102, 253-273 (1975)

Minteer, B. A. & Collins, J. P. Ecological ethics: building a new tool kit for ecologists and biodiversity managers. Conservation Biology 19, 1805-1812 (2005a).

Minteer, B. A. & Collins, J. P. Why we need an "ecological ethics." Frontiers in Ecology 3, 332-337 (2005b).

Pickett, S. T. A. & Ostfeld, R. S. 1995. The shifting paradigm in ecology. In A New Century of Natural Resource Management. eds. Knight, R. L. and Bates, S. F. (Washington: Island Press, 1995), 155-170.