« Prev Next »

An Introduction to Wildlife Management

Wildlife is a collective term for any non-domesticated species of animals or plants. In common usage, however, the term is generally applied to non-domesticated, vertebrate animals, typically terrestrial ones. Within this more restrictive definition, animals may be classified as either game or non-game species. Game species are those which either are or have been traditionally harvested by humans.

Game harvesting is the taking of wildlife by hunters or trappers, analogous to the harvesting of plants by farmers. Harvesting of wildlife is done for a variety of reasons. Game animals may yield valuable products. These products include furs, hides, bones, teeth (especially tusks), meat, and a variety of other products used in traditional ceremonies or medicines. For example, in South Africa, endangered vultures are illegally harvested for “sangomas” (witch doctors or traditional healers, depending on your point of view) to develop magic to allow the purchaser to be successful in playing lotteries, as vultures are assumed to be able to see into the future. Game animals are routinely hunted for sport or as part of cultural ceremonies, such as rites of passage. In western Kenya and Tanzania, killing lions was formerly an activity young Masaai men did as part of achieving “moran” (warrior) status. Animals may also be hunted or trapped for various mitigation purposes, such as reducing human-wildlife conflict. One of the most infamous examples of government-supported eradication of wildlife to mitigate conflict was the establishment of bounties on coyotes by the United States government in the early decades of the twentieth century. The end result was that coyotes evolved into smarter, more adaptable animals, and the species has now spread throughout the entire continental US whereas it was formerly found only in central and western states. More recently, in order to prevent collisions of birds with airplanes, shooting programs have been enacted at many airports. At John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City, more than 63,000 laughing gulls were shot during the 1990s, according to the US Fish and Wildlife Service (Dolbeer et al. 2003). Finally, within the last two decades, the dramatic growth of ecotourism, especially wildlife tourism, has led to a new valuation of game resources based on nonconsumptive uses such as wildlife photography, shark cage diving, “green” hunts (e.g., darting safaris, in which game animals are tranquilized rather than killed), and paid participation in wildlife research through such organizations as Earthwatch (Figure 1).

To prevent the depletion of wildlife resources, usage of species and their ecosystems must be regulated. These regulatory efforts may include setting harvest limits and methods, protecting wildlife habitat, educating the public, enforcing game laws, researching wildlife ecology, mitigating human-wildlife conflict, etc. Collectively, these activities are termed wildlife management.

Who Manages Wildlife?

In most countries, wildlife management is a governmental function: the exploitation of wildlife is regulated by an agency with the legal authority to enforce wildlife laws. In many countries, the central government may have primary management responsibility. In other countries, state or provincial governments have primary management responsibility. In North America there is a mix of these two. Wildlife are held in the public trust, and a combination of national, state, provincial, or tribal governments have responsibility. In other countries, notably South Africa, much game management is devolved to landowners who have ownership rights over the wildlife on their lands. In countries with no strong central government, with civil unrest, or with poor food security, little management authority may be exercised, placing game populations in extreme jeopardy.

In the absence of human influence, there is typically no need to manage wildlife, as ecosystems evolve some degree of self-regulation. However, nearly all ecosystems are now heavily impacted by human activities, including expansion of agriculture, logging, mining, and urbanization (all of which result from the growth of human populations). Game animals are among the first natural resources to be depleted by these activities, either to feed workers (as an alternative source of income for workers) or as collateral damage as other resources (e.g., timber, mineral resources) are exploited. As a result, in most situations game management is necessary to prevent the overexploitation or even extirpation of game species.

Nearly all countries participate in one or more treaties that govern the use of fish or wildlife resources. The broadest and best known treaty is CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), enacted in 1975. This treaty, of which 175 countries were signatories in 2010, prevents international trade in such products as elephant ivory, rhinoceros horn, skins or other parts of large cats, etc. (Figure 2). Even though these species may be common and even legally harvested in some countries, those countries are still prohibited from trading in these species to prevent the development of an illegal international market that may promote the endangerment of these animals.

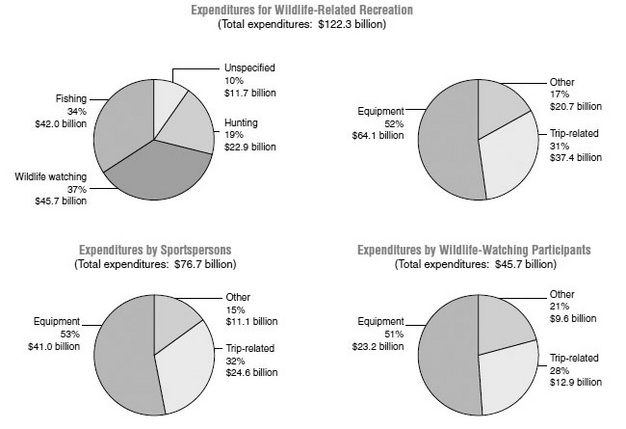

Governments and/or other governing agencies also manage the harvesting of wildlife for economic reasons. The sale of hunting and trapping licenses and taxes on hunting equipment and other expenditures by hunters are significant sources of income for some governments. For example, there is a federal excise tax on hunting equipment such as bows and ammunition in the US.

Excise taxes in 2009 generated nearly $473 million in apportionments returned to states in 2010 (US Fish and Wildlife Service 2010). The revenue supports wildlife restoration and educational programs at the state level. In addition, some states (e.g., Missouri) have enacted similar legislation, augmenting the resources available for game management.

The private sector also frequently has a direct economic interest in managing game resources. In post-apartheid South Africa, hunting and ecotourism have driven the rapid proliferation of private hunting ranches and game preserves, which are now a significant source of income and represent more land area than public reserves. Compiling data from a variety of sources, Bothma et al. (2009) estimate annual returns of as much as $259 USD per hectare from private nature reserves and ranches. As an ancillary benefit, much natural habitat is also preserved, which protects many non-game species as well.

However, wildlife management can incur certain costs through the destruction of crops or other property, opportunity lost (e.g., the maintenance of wildlife habitat that could otherwise be converted to agricultural or other production), maintaining reservoirs of diseases, or direct attacks on humans.

The Philosophical Evolution of Game Management Practices

These approaches to wildlife management frequently led to mismanaged game populations. In reaction, a managerial model developed, in which particular species are intensively managed as natural resources to provide sport or income, often by professional game managers. Examples include the pen-raising of game birds for release on shooting preserves in the UK and US, the intensive trade in individuals of desirable species among game ranches in South Africa, and hatchery management of many game fish, especially trout and salmon, particularly favored by European sport anglers.

Another reaction to mismanaged populations was the development of a legal approach to protecting wildlife resources. Strict laws to protect animals (as opposed to royal mandates) were developed and enforced. These laws typically established a public agency with responsibility for game management and the enforcement of related laws. These agencies usually have the authority to impose new regulations on game harvesting. Both the managerial and legal approaches to management are responses to the overexploitation or abuse of wildlife resources and/or their users. Traditional societies may also have socially-enforced rules concerning wildlife use, essentially informal laws developed to manage wildlife resources.

In the twentieth century, the rise of ecology as a science, a global awareness of environmental ethics, and the emergence of the multidisciplinary science of conservation biology have led to an ecological philosophy of wildlife management in which the rights of other species to exist and the interconnectedness of species and their resources are recognized. This approach values all wildlife, not just game species, and typically focuses on managing habitats and ecosystems, not just individual species, although the management of individual species is still common especially for species that are heavily harvested or endangered. (Figure 3).

The Future of Game Management

References and Recommended Reading

Recommended readings:

Begon, M., Townsend, C. R. et al. Ecology from Individuals to Ecosystems, 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Bolen, E. G. & Robinson, W. L. Wildlife Ecology and Management, 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003.

Bothma, J. du P., Suich, H., et al "Extensive wildlife production on private land in South Africa," in H. Suich, B. Child, et al. eds. Evolution & Innovation in Wildlife Conservation. London, UK: Earthscan Publications, 2009.

CITES Secretariat. Official website of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. (link)

Dolbeer, R., Chipman R., et al. Does shooting alter flight patterns of gulls: case study at John F. Kennedy International Airport. International Bird Strike Committee Conference. Warsaw, Poland. 2003. (link)

Ntiamoa-Baidu, Y. Wildlife and Food Security in Africa. New York, NY: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1997. (link)

Sinclair, A. R. E., Fryxell, J. M. et al. Wildlife Ecology, Conservation and Management, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2006.

U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, and U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau. 2006 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, 2006. (link)

U.S Fish and Wildlife Service. Certificate of apportionment of $472,719,710 of the appropriation for Pittman Roberston Wildlife Restoration (DVDA No. 15.611) to the states, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands for fiscal year 2010. (link)