« Prev Next »

The book list was an ambitious list, and it included both classics in the subject and more modern books: Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, which I'd somehow never read, John McPhee's Encounters with the Archdruid, Bill McKibben's End of Nature, Thomas Friedman's Hot, Flat and Crowded, and many, many more. I didn't read all of the books on the list and I don't think I've ever written a piece solely about any of the books on that list I've actually read. But that reading informs the writing I do every day, and it helps me add context and depth.

The End of Nature, for instance, contains two tidbits I come back to over and over again. They're early in the book, when McKibben's covering James Hansen's work on climate change at NASA. This was Hansen's early work, in the late 1980s, when he was one of the first scientists to start talking about the dangers of climate change. He and his colleagues had started modeling the effects of increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and they thought that these changes—heat waves, in particular—"should begin to be obvious to the man in the street by the early 1990s at the latest," McKibben writes. And, he notes, warming was happening already: another group of scientists had found that the six warmest years on records were "in order, 1988, 1987, 1981, 1980, and 1986."

These two little bits of information are important to me because they show how hard it has been for scientists and journalists to talk about climate science—so much so that we're still telling the same stories as we were two decades ago, in the first popular book on the subject. It has not become obvious to the man on the street that climate change is happening (although this summer's heat wave did convince some people, at least for the moment). That's true even though the planet has continued to heat up: the six warmest years on record now are, in order, 2010, 2005, 1998, 2003, 2002 and 2009. Climate writers are still trying to figure out the best way to communicate these hard truths to people.

Because I so often want to reference it, I'm glad I invested in my own copy of this particular book. But some of the books that have helped me the most have come to me fortuitously, through the graces of the publishing industry. One of the lovely perks of working in the media is that people will send you books for free. If you can lay claim to a substantial enough audience, often all you have to do is ask for a review a copy of a book to have it sent right to your front door or delivered to your Kindle. Right now, for instance, I have a new history of drinking water on my desk that I'm very excited about. Vance Packard's The Waste Makers, published in 1960, helped me understand how long writers and thinkers have been arguing against disposable, advertising-driven consumer culture; I only thought of reading it because Ig Publishing sent me a copy of its re-released edition.

As an environmental journo, though, I also have to advocate for the other way to get books for free—taking them out of the library! It helps, of course, if you live somewhere like New York, where the public library system has basically every book you'd ever want to read and will deliver it to the branch most convenient to you. That's where the copy of the book I'm currently reading—Mark Fiege's The Republic of Nature—came from.

If some books help put science in historical context, Fiege's putting history in scientific context. He writes about some of the most familiar episodes of American history and manages to connect them to science. The Salem witch trails, he links to demanding land use practices of colonial farmers. When he writes about slavery, he focuses on the life cycle of cotton plants. Cross-breeding of cotton plants, for instance, leads to more productive varieties—so productive that some masters paid slaves to pick above their usual quota or to work on Sundays, in order to reap the largest harvest possible. These varieties of cotton, Fiege writes, changed the balance of power, even if just a little bit, between masters and slaves.

I don't know how this particular book might influence what I write in the future, but reading it still feels like a good investment. Perhaps it will shift the places I look for science stories: who would have imagined that there'd be an environmental angle to the Salem witch trials?

--

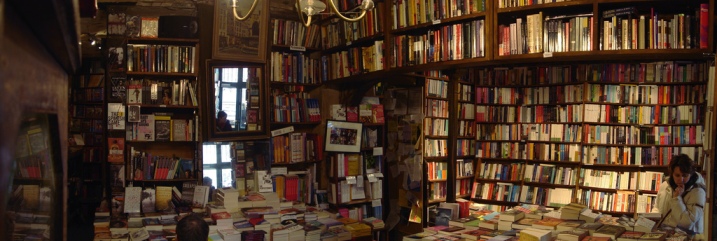

Image credit: Alexandre Duret-Lutz (from flickr).