« Prev Next »

My family still thinks it a bit strange that I'm a journalist. When I was younger, I was shy, and as a big ol' introvert, I'll often need a break after spending time with big groups of people. So it's strange to them that I've chosen a job that involves picking up the phone and cold calling people or approaching strangers and asking them questions.

The longer I've been a journalist, though, the more I've heard and collected comments from other reporters-great reporters-who are shy or who hesitate to approach subjects. There are lots of them. John McPhee, for instance, told NPR last year: "When I first go to interview someone is something I'm not very found of... it's hard to walk in through the door and start talking to somebody."

He gets around this problem in part by writing long stories, in which he gets to spend time with his subjects, instead of meeting new ones every day. For me, one trick is to remind myself that, always, inevitably, picking up the phone or going out the door will get me better, more interesting information. Often, I'll get it more quickly than if I tried to find it noodling around the internet. Plus, some of the best information isn't out there yet.

Last year, I was covering green technology, a topic which can get pretty geeky. There's a lot of research aimed at improving biofuels, for instance, and most of it has to do with finding better enzymes to digest different plant-based sources of energy more efficiently. (The more efficient the process, the more affordable and commercially viable biofuels will be.) This idea for this post started out along those lines: a team at Tulane had come up with a quirky fuel source: newspapers.

As they were aiming to get press attention, highlighting newspapers was a smart move. Journalists are suckers for newspapers. The real focus of the research, though, was a bacteria, called TU-103, which produced the biofuel butanol in an aerobic environment. And what I found more interesting than what it ate was where the team had found it-a bit of information that I learned only when I got on the phone.

The bacteria, it turned out, had come from New Orleans' Audubon Zoo. The bacteria that live in the digestive tracts of animals are really good at breaking down cellulose and other plant material into simpler compounds. Scientists are looking for bacteria and enzymes that do exactly that. In practice, that means that this particular team picked up feces samples from zoo animals and profiled the bacteria they found there.

But other teams, it turned out, had gone to Costa Rica to source bacteria from the guts of the many species of termites that live there. A team in Mississippi had look to panda poo. Less exotic creatures, like cows, had also had scientists poking around their rumens to find promising specimens. I thought the idea was fun enough that I wrote another post on it. (The New York Times thought it was an interesting idea, too, so I feel safe saying I was right!) It's experiences like these that remind myself of when I'm sitting there, convincing myself that I have enough material, that I don't need to call the next person on my list of potential interviewees. There's always another great fact out there.

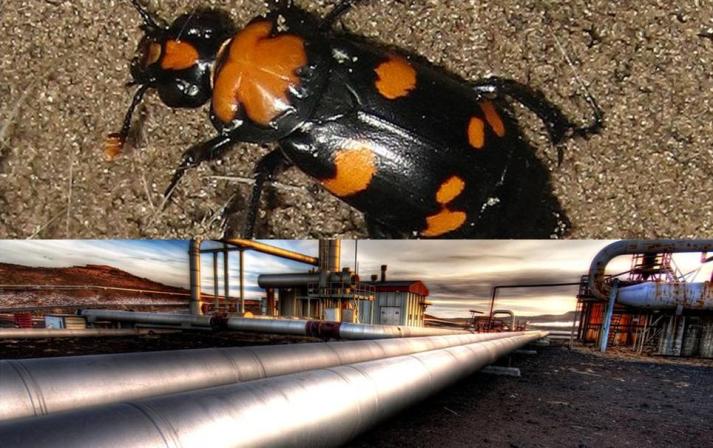

One of the stranger aspects of this lede, though, was that it was for a story about politics. American burying beetles live in significant numbers right in the path of the controversial Keystone XL pipeline, and environmental groups and TransCanada, the company building the pipeline, had been fighting over the proper timing of moving them. There was science involved-the inconvenient timing of the beetles' lifecycle was what had opened up the political sparring ground, and one of the most important interviews I did was with the biology professor who oversaw the work of moving them. But since it was a political story, most of the people I was talking to were interested in the American burying beetle less as a topic of scientific inquiry and more as a means to an end.

One of the first things you learn about science is that objectivity is paramount. In politics, the opposite is true. In environmental reporting, the two often collide, and political forces try to enlist the power of science's objectivity to prove that their particular viewpoint or goal is the correct one. Follow the political fight over natural gas drilling, for instance, and you'll find both drilling proponents and opponents citing scientific papers that support their position.

To a certain extent, these are legitimate disagreements: scientists don't always agree, and new evidence can call into question the prevailing theory. But in the most extreme version of this, one side will cling to the few studies that support their position, even when that work is well outside the prevailing scientific consensus. The example that comes up most often right now is the political argument over climate science, but it's not an exclusively right-wing trait: Keith Kloor, for instance, has been making the case for a while now that left-leaning environmentalists are just as guilty of cherry-picking science about the dangers of genetically-modified crops to shore up their dislike for the GMO industry.

As a reporter covering a political story where science plays a role, this can mean that it's that much more important to check where the science is coming from-who's funding it and what the background of the researchers is. But it can also mean that there are people out there who are familiar with the issue that you're writing about and are more committed to giving you accurate information about the science than political sources might be.

In the case of Keystone XL and the beetles, the political and legal logic of this particular fight led this giant company to hire a biology professor and a team of grad students to motor around Nebraska, setting traps for the beetles, an activity which involved burying large buckets in the ground and baiting them with dead rats. When I first heard about this issue, I knew that the story would work best if I could talk to that biology professor. TransCanada wasn't likely to have much to say about this unsavory project, but I wanted to talk to someone other than the environmental groups, who were interested in the beetles' fate but also in the larger political project of blocking the pipeline's construction. Although the professor was working for the company, he was also a scientist and probably cared more about the beetles than the environmental groups that had gone to court to defend them.

He turned out to be a great person to talk to, precisely because he was a scientist. He gave me great details about burying beetles and methods of trapping them. But he also ended up speaking candidly about the potential negative impact on the beetles (which the environmental groups wanted to play up and the company wanted to play down) and about the legal gray area that had let him capture them to begin with. It's not always that easy. But in this case, the combination of science and politics made the job I had to do that much more fun.

--

Image credits: American burying beetle: USFWS Mountain Prairie (from flickr); Pipeline: Trey Ratcliff (from flickr).

The book list was an ambitious list, and it included both classics in the subject and more modern books: Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, which I'd somehow never read, John McPhee's Encounters with the Archdruid, Bill McKibben's End of Nature, Thomas Friedman's Hot, Flat and Crowded, and many, many more. I didn't read all of the books on the list and I don't think I've ever written a piece solely about any of the books on that list I've actually read. But that reading informs the writing I do every day, and it helps me add context and depth.

The End of Nature, for instance, contains two tidbits I come back to over and over again. They're early in the book, when McKibben's covering James Hansen's work on climate change at NASA. This was Hansen's early work, in the late 1980s, when he was one of the first scientists to start talking about the dangers of climate change. He and his colleagues had started modeling the effects of increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and they thought that these changes—heat waves, in particular—"should begin to be obvious to the man in the street by the early 1990s at the latest," McKibben writes. And, he notes, warming was happening already: another group of scientists had found that the six warmest years on records were "in order, 1988, 1987, 1981, 1980, and 1986."

These two little bits of information are important to me because they show how hard it has been for scientists and journalists to talk about climate science—so much so that we're still telling the same stories as we were two decades ago, in the first popular book on the subject. It has not become obvious to the man on the street that climate change is happening (although this summer's heat wave did convince some people, at least for the moment). That's true even though the planet has continued to heat up: the six warmest years on record now are, in order, 2010, 2005, 1998, 2003, 2002 and 2009. Climate writers are still trying to figure out the best way to communicate these hard truths to people.

Because I so often want to reference it, I'm glad I invested in my own copy of this particular book. But some of the books that have helped me the most have come to me fortuitously, through the graces of the publishing industry. One of the lovely perks of working in the media is that people will send you books for free. If you can lay claim to a substantial enough audience, often all you have to do is ask for a review a copy of a book to have it sent right to your front door or delivered to your Kindle. Right now, for instance, I have a new history of drinking water on my desk that I'm very excited about. Vance Packard's The Waste Makers, published in 1960, helped me understand how long writers and thinkers have been arguing against disposable, advertising-driven consumer culture; I only thought of reading it because Ig Publishing sent me a copy of its re-released edition.

As an environmental journo, though, I also have to advocate for the other way to get books for free—taking them out of the library! It helps, of course, if you live somewhere like New York, where the public library system has basically every book you'd ever want to read and will deliver it to the branch most convenient to you. That's where the copy of the book I'm currently reading—Mark Fiege's The Republic of Nature—came from.

If some books help put science in historical context, Fiege's putting history in scientific context. He writes about some of the most familiar episodes of American history and manages to connect them to science. The Salem witch trails, he links to demanding land use practices of colonial farmers. When he writes about slavery, he focuses on the life cycle of cotton plants. Cross-breeding of cotton plants, for instance, leads to more productive varieties—so productive that some masters paid slaves to pick above their usual quota or to work on Sundays, in order to reap the largest harvest possible. These varieties of cotton, Fiege writes, changed the balance of power, even if just a little bit, between masters and slaves.

I don't know how this particular book might influence what I write in the future, but reading it still feels like a good investment. Perhaps it will shift the places I look for science stories: who would have imagined that there'd be an environmental angle to the Salem witch trials?

--

Image credit: Alexandre Duret-Lutz (from flickr).