« Prev Next »

In today's podcast, Ilona talks to David Shenk, from theAtlantic.com. David is a writer and author of many books about the intersection of science and culture. His recent book, The Genius in All Of Us: Why Everything You Know About Genetics, Talent and IQ is Wrong, debuts in March 2010. In it he argues for a new way of thinking about genes and notions of inherited intelligence. David has advised the President's Council on Bioethics, and is a keen observer of how science is reported. Listen to this podcast to learn how David's arguments can inform how we judge aptitude, and how intelligence depends heavily on context. [16:59]

In today's podcast, Ilona talks to David Shenk, from theAtlantic.com. David is a writer and author of many books about the intersection of science and culture. His recent book, The Genius in All Of Us: Why Everything You Know About Genetics, Talent and IQ is Wrong, debuts in March 2010. In it he argues for a new way of thinking about genes and notions of inherited intelligence. David has advised the President's Council on Bioethics, and is a keen observer of how science is reported. Listen to this podcast to learn how David's arguments can inform how we judge aptitude, and how intelligence depends heavily on context. [16:59]

![]()

Full transcript

ILONA MIKO: Welcome to the latest edition of Nature Edcast by Nature Education. I'm Ilona Miko, and today we're talking to David Shenk from theAtlantic.com, about the genetic basis of intelligence. David is a writer and author of many books about the intersection of science and culture. His recent book, The Genius in All of Us: Why Everything You Know About Genetics, Talent and IQ is Wrong, debuts in March 2010, and in it he argues for a new way of thinking about genes. David has advised the President's Council on Bioethics, is an avid watcher of how science is reported, and he likes to think about how we consume it. Welcome, David.

DAVID SHENK: Thank you. Thanks so much for having me.

MIKO: Thanks for joining us. One of the main messages of your book is that intelligence or talent is not a thing but rather a process. Would you explain that, tell us what does that mean?

SHENK: In our culture, we tend to talk about people possessing a certain amount of intelligence or a certain type of talent. Each of us is said to be a gifted musician or athlete, or were not lucky enough to be gifted with those talents. Or people say we are born with a certain kind of intelligence — we're innately intelligent or we aren't. And we got all these myths and phrases that reinforce that idea — that talent and intelligence are these things that we possess and that we are largely born with. One of them, just one of the many, is the hole trope of IQ tests and this IQ number, this IQ score, that each of us supposedly has this kind of this that represents the amount of intelligence that we're born with. The trouble is that when you take, thankfully I should say, when you take a close look at what makes people really good at stuff, or really smart about stuff, and you look at the science behind that, and the science is getting so exciting in the last, say, decade or so, it turns out to be all about the acquisition of skills, about the changes that take place in the brain and the body as we acquire skills, as we acquire perspective, as we acquire intelligence. So if you look around at the people who were really studying this, you see people like Robert Sternberg of Tufts, who is perhaps our preeminent expert on intelligence now, who talks about intelligence being a set of competencies in development. It's all about development; it's not about something that you just kind of have born in some gene in your genome. The reason that this hasn't really been articulated well is that up until really recently, this process of development was basically impossible to see. I mean after all, if intelligence is made up of a series of skills — of competencies, and of talent (or musical or athletic or other sorts of talent) — are made up of all these different skills, they actually represent tiny, tiny, tiny increments of improvement over many, many, many years time. And how do you see those tiny little increments? How do you make that visible? And the science of that was very, very tricky. But thankfully we now have, thanks to people like Anders Ericsson and many, many other people setting the science of expertise (or people call it various things), we now have this whole body of science that's emerging that shows us — it's beginning to show us this process. So I'm trying to help people understand and think about intelligence and talent in a whole new way. I'm saying, let's reject the old paradigm of talent scarcity where we used to think of the world as being made up of some people who were lucky enough to be born with certain talents, and then some of those people were lucky enough to have their talent, their talent gems polished and turned into great achievers. And let's instead to imagine where the science is pointing us, which is to a world that has really an extraordinary amount of potential — where instead of talent scarcity, this just an incredible amount of talent potential, arguably in all of us. Obviously we're all different beings, and so the potential is going to be different. But it really is this idea that we really haven't tapped into so much of our talent. And let's think about that is a whole new paradigm. That's the basic argument of my book.

MIKO: One of the ways that you talk about this is that intelligence is not inherited, like one would think of the notion of the genome as a set of inherited genes that you get from your forebears. What is wrong with the analogy of the genome being a genetic blueprint? What other analogy could be used to help understand the malleability, as you say, of what we inherit?

SHENK: Yeah, well, it's a struggle to come up with the right metaphor, and I think that's one of the reasons that we've been stuck with this old distracting, arguably dangerous, metaphor for so long. What I'm doing in the book regarding genes is — and people will know that I'm not a scientist, or they're hearing it now, so I'm not pretending to be a scientist — I'm following the lead of just a whole bunch of really great scientists who are out there in the forefront, not only understanding the stuff, but also trying to articulate the other people, like Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb and Michael Meaney and Patrick Bateson, all these people who are trying to help us understand genes in a whole new way. And for example, Michael Meaney points out there are no genetic factors that can be studied independently of the environment. Everything about genes is about how genes interact with the environment. And we used to thinking of genes as possessing this kind of information that then becomes a certain trait or a set of traits. And it's true that genes do possess information, and genes have a huge influence on all of our traits — there's no question about that, and genetic differences do matter. But getting from point A to point Z, getting from the gene to the actual trait in question, is always going to involve this really, really interesting dynamic interaction between genes and the environment. It's genes getting, instead of genes being these robot actors who are kind of speaking the same lines all the time — the same gene that will always in the same thing no matter who possesses it — it's really something very different. It's genes being turned on and off all the time, constantly; genes expressing themselves and not expressing themselves, depending on the specific environment that they're in.

MIKO: So getting back to this notion of intelligence as heritable, where did that come from, the idea that intelligence was fixed and came somehow from your lineage? Where did that whole idea get started, about the genetics of intelligence?

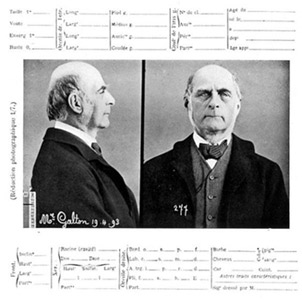

SHENK: Yeah well, the history of this is just absolutely fascinating. And we could talk for an hour about it. I'll try to give you just a few-minutes summary. The story really begins with a guy named Francis Galton, who was a distant cousin of Charles Darwin — and who actually lived near, fairly close to Darwin — and corresponded with him, and really was tracking Darwin's work as he was writing On the Origin of Species. And as soon as it came out, Galton immediately was one of the first people to take advantage (and really I think we can say, exploit, not in a mean-spirited way), but really try to exploit the power of Darwin's argument. And Galton had these very specific views about what made people great at stuff, what made people smart and talented. And his views were that they were inherited biologically. He was very, very certain about that, with frankly no evidence to back that up, but he was actually convinced of that. And he basically kind of appropriated Darwin's views into his argument, and shortly, ten years, after Darwin's book was written he published a book called Hereditary Genius, which argued that genius and intelligence were the result of these hereditary transmissions of physical gifts. And from there we started basically a century of these fairly prominent, or very prominent, scientists kind of passing on their ideas to one another and then plugging it into the science of the time. So after Galton comes Charles Spearman, who came up with this concept of general intelligence, which is kind of a statistical invention which he was actually convinced, like Galton was with his inherited thing. And he kind of passes on to Lewis Terman, who appropriated the IQ test, who then was very, very prominent in the early part of the 20th century, and again saying that this had to be a part of an original endowment — this IQ, this intelligence.

MIKO: So it seems to me that Galton has a lot to do with the beginning of the ideas of eugenics and of genetic determinism. And so, these days, of course we don't teach these in our classes, but we sort of take something that does them from Galton's early views, is the sort of artificial dichotomy of nature versus nurture: is something endemic to an organism, or is something learned by an organism by virtue of its interaction with its environment? So can you tell a little bit about how that's evolved, and how, whether or not, we can still use that in the way we teach our friends and our students about the origin of behavior and certain traits? And how can we use the new modern understanding of genetics to inform some of the ways we talk about it now in a more evolved state?

SHENK: Yeah, absolutely. Galton actually was the one who introduced in the phrase, nature and nurture, and he had taken it from Shakespeare and from one other source. And his purpose of using that phrase was really to turn it into nature versus nurture and basically to use it as a sell tool for furthering nature, frankly. So this is a very powerful phrase. It doesn't roll off the tongue (and I don't think I ever got to get rid of it), so my view is instead of arguing that we need to get rid of it, let's turn on its head and let's plug it in to what we now know. And whereas we're used to thinking of nature and nurture as these very separate things — nature representing our genetic inheritance, nurture representing our parents and our culture and our schools and so forth — the reality is that these things are constantly interacting and it's really not, this is not my idea (this really, Matt Ridley was the one who really expressed this beautifully not so long ago), but the idea is that it's now nature via nurture, or nature just constantly interacting with nurture. In my book, in drafts of my book, I actually played with like kind of interspersing the two words and coming up with this nature nurture nur-nur-nur. It didn't quite make it to the editing passes, but still I think it's, the idea is it's nature interacting with nurture, and if people kind of understand that they're not opposing one another and that is no real way to separate the two. We can't say, "Oh, there's this nature thing over here that gives you part of your intelligence or part of your talent. It really is this dynamic process that's going on.

MIKO: So how can we use this kind of viewpoint of intelligence that's becoming more popularized? How can we use in the classroom, like say, when educators teach the science of genetics? How can we use this to think about the potential of students?

SHENK: Well, I think the key is going back to this idea of process and helping people to realize that while none of us have entire control over who we are or where we came from or where were going, and there is many, many influences (not only genetic) that we can't control: we can't control our parents; we can't control so many things about our culture or our media. There are things that we can control, and we really can, together with our parents and our teachers and all the things that influence us and the choices we make, we really can have an amazing impact on our lives, on our abilities, if we have the right attitudes, if we are passionate about becoming better at a certain thing or a certain collection of things. The potential for malleability, for the way that we actually change the way our brain is shaped — this well known plasticity that we all have now.

MIKO: Do you think that this should change our ideas about testing and test results?

SHENK: Well, what we need to do with testing is just, we have to really get past this idea of that tests are revealing something about the core of ourselves that doesn't change. Tests are always revealing our abilities as they are in that moment. They're useful. They're useful to compare what we've learned and what we don't know, and what the teachers can then try to make up for and what strategy and what learning and teaching strategies are or are not working. But they're only revealing that point in time. They're not revealing any kind of core or limit or ceiling about what we are or who we can be.

MIKO: More like they're revealing a weakness or what a kid might need to work on.

SHENK: Exactly.

MIKO: Going forward. All right. Well, thanks, David, for joining us today. That was really interesting.

SHENK: My pleasure.

MIKO: Thank you for listening to this edition of Nature Edcast. You can find this podcast and others at nature.com/scitable. That's nature.com/s-c-i-t-a-b-l-e. Please join us again next time.

I liked "Nature via Nurture" phrase. It summarizes everything in this subject