« Prev Next »

Chances are you've been through it before: the agony of falling in love and suffering a break-up.

Your heart bursts at the mention of their name. Every song on the radio seems to speak to you. Every mundane happening of your day serves as a sadistic reminder of things that once were.

We often speak about break-ups in terms of physical pain, but it is still not clear to what extent emotional pain reflects the biological happenings in the brain.

Is it painful? Yes. Permanent? Not so much.

So how does such a sudden loss affect the neural circuits that underlie behavior? And what does it take to get over the ‘brain-break' of a break-up?

The interruption of social ties and attachment elicit a body-wide distress response. In fact, brain regions that control responses to distress and physical pain, such as the dorsomedial thalamus and parts of the brainstem, have been shown to be particularly active in the brains of those suffering loss. These parts of the brain that control the pain response act up as if something awful is happening; from a psychological and physiological perspective, something awful often is happening.

Humans are wired for social interactions; our very health depends on making and maintaining healthy relationships. When we are close to a partner, our reward system activates, secreting powerfully rewarding neurotransmitters that make being close to our partners an immensely rewarding human experience. Furthermore, there is evidence that healthy social relationships even contribute to longer life expectancy. Given our dependence on relationships for good health, it makes sense that the pathways linked to social attachment are also responsible for physical pain. Loss is undeniably painful, and now there is physiological evidence to support this.

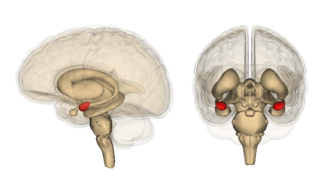

Many imaging studies suggest that activity between the amygdala and prefrontal regions of the brain regulate attention and sadness during pangs of grief. This might explain why it's so difficult to concentrate on anything during the mourning period that follows a break-up. Variations in this circuitry may even be used to distinguish between differences in grief style and indicate the individual's gender, since men seem more likely to distract, while women may be more likely to ruminate.

Going through a break up can also elicit feelings more closely related to that of addicts going through withdrawal.

When you experience feelings of love, the brain's reward system triggers the release of dopamine in the caudate nucleus and ventral tegmental areas. Furthermore, not only does this system provide pleasure at first, but over time, provides relief from distress, and can also resemble withdrawal when denied this kind of behavior or outcome.

It well may be. When we have lost something or when a relationship ends, the individual responds with sadness, a signal that we should give up a possibly senseless goal and try to obtain a new, more manageable one.

The good news, at least, is that according to studies on neural pathways and emotion, healing from a break-up comes down to re-wiring the brain. In fact, imaging studies suggest that heart-broken brains also show high activity in the areas of frontal cortex that inhibit our impulses and redirect behavior.

So the next time you find yourself thinking about that ex-someone, don't be so hard on yourself. Your brain is doing everything it can be doing to get over it.

As it turns out, time (and neural plasticity) heal all psychological wounds.