In 2013 Mériam's husband kidnapped their daughter and left to join the jihad in Syria. Once there he began sending chilling text messages back home, expressing his wish to die as a martyr alongside their child. By the time our disindoctrination team got to Mériam, she was distraught. We advised her to keep communicating with her husband and to follow one basic rule: Do not confront him about his ideology or his plan. Instead focus on his memories. Remind him about the day you met, the birth of your child, the places you visited together.

For 10 months, nothing. Then one day, for no apparent reason, there was a change. He had remembered a romantic evening at a restaurant, a moment of peace. This was good news. His emotions were not yet dead. Eventually he agreed to meet Mériam at a hotel on the Turkish border. There she reclaimed her child, her husband was arrested and they all returned to France.

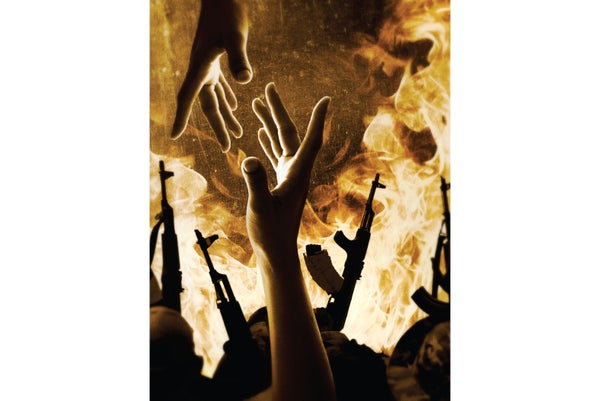

Mériam's case illustrates a fundamental truth we have discovered in our work with more than 500 families in France who had a loved one caught up in Islamic extremism: There is no room for reason. You must reach out to radical recruits using emotion—which is easier said than done. As soon as Mériam received her husband's reply, all she wanted to do was tell him that his plan was crazy and that he urgently needed to come home. We convinced her to stay calm, to continue to revive his past memories and to remember that her husband had lost touch with a great part of his humanity.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

How did he become so lost in the first place? How did he become a pawn in the radicalization machine?

Recruiting Steps

In our experience, many kinds of people are vulnerable—from teenagers who are flunking out to those who are first in their class. Radical Islam not only lures Muslims, it attracts Christians and even Jews, who make up about 3 percent of our caseload. Most had been uninvolved in religion. Some 50 percent are not recent immigrants; they are from families living in France for many generations. Also, only 30 percent of the families who ask us for help come from working-class backgrounds. Perhaps they are more fearful of authorities than middle-class families, who usually have more confidence in publicly funded institutions and contact us sooner.

Despite this diversity, extremists enlist everyone using the same four steps. First, they isolate the recruit—most often a teenager or young adult—from his or her social environment. Ideological recruitment rhetoric, often on the Internet, convinces them that they live in a world in which adults and society lie—about food safety, medicine and vaccinations, history and politics. The recruiters mix verifiable facts with unverifiable elements so that susceptible young people snared in their web start to doubt everything. They tell them that “secret societies”—a Zionist conspiracy, the Illuminati, the Freemasons—are “buying up the planet.”

Against this backdrop, a young recruit soon finds himself—the target is often a male—in a peculiar situation. In the familiar and secure atmosphere of his room, he goes from YouTube link to YouTube link, feeling drawn into precisely the world he wants to reject. Recruiting Web sites cleverly reference films such as The Matrix, in which the protagonist, Neo, wonders if he should take a pill that will wake him up and show him the truth about reality or if he should go on sleeping, blissfully oblivious.

At this stage, the recruit abruptly stops seeing his friends, deeming them blind to reality. He abandons his hobbies because they prevent him from participating in the “revolution.” He also stops going to school, believing his teachers are paid to make him docile and prevent him from exposing the ubiquitous lies. Eventually he shuns his family. If his parents do not agree with him, they, too, must be blind, asleep or, worse, sellouts to the system.

During the second phase of recruitment, handlers tell the isolated teen that only true Islam can renew and reawaken him. He gets a clear message that he is among the chosen people, who are more discerning than the rest. To be integrated into that group, he will adopt clothing that erases his individual look. He will disappear into the common group identity. This transformation begins to dissolve his memories of his past. From that point on, the group thinks for him. His family, if they are in touch, finds it impossible to have a discussion. He answers only with words from the Prophet, out of context, which he keeps repeating, as if some other entity is thinking for him.

In the third step, a now fully indoctrinated teenager will adhere completely to the radical group's ideology. He is convinced that he is chosen and accepted into a community possessing the truth. The supposed purity and importance of the group are very powerful concepts at work in his mind. He believes that he must not associate with or be contaminated by anyone who does not think as it does.

The fourth and last stage of recruitment is dehumanization. Initially other people are dehumanized: all those who do not follow the recruit's same path of “awakening” are considered not really human; killing them is not a crime and is even a duty. Then dehumanization applies to the recruit, too, as the ideas and emotions of the group supplant his own. Within the group itself, emotional ties among individuals exist only through the group. For example, we tried to “rehumanize” one woman by reviving her ties with her husband. But this approach failed miserably because, as the team later realized, she had an emotional connection to him only because he was also radicalized and planned to die for “the cause.” The barbaric acts of cruelty that radical groups engage in, such as suicide bombings and decapitations, further destroy a recruit's sense of humanity.

Breaking the Spell

Once victims have been fully radicalized via these four phases, what are the chances of getting them to reconnect with their past and future? Recovery always begins by rekindling an emotional connection with family members. The problem is that by the time the family contacts us for help, the break is often complete: the teen no longer considers his parents his parents. We must then work patiently and deftly to rebuild these attachments.

Fortunately, the human brain always preserves traces of past feelings, which can surface at unexpected moments. Parents need to think of pivotal events in their child's life and recall their interactions. This process is exceptionally difficult on parents. Some young people destroy images in the house forbidden by radical rhetoric, break the televisions (seen as vectors of the Illuminati ideology) or refuse to eat (for fear of pork gelatin in the food). The only way to tap their emotions is by recalling remnants of their former life—perhaps a childhood photograph, enlarged and left around the house, or a souvenir from a family trip. Such tactics can have surprising results. As long as parents remain extremely patient (for months, they must not attempt to address the problem with rational arguments), this method eventually bears fruit.

“Resensitized,” a teenager may then, using one excuse or another, reluctantly consent to go to a support-group meeting. At this point, our team jumps into action. For instance, we assisted one family whose son, in the course of being radicalized, was focused on rejecting alcohol. His own jihad was to destroy any trace of alcohol in the house: deodorants, perfumes, food products—all had to go. For several months his parents had worked toward an emotional reactivation, little by little. And then, for Mother's Day, the teen gave his mother a bottle of perfume. She called us in tears. We told her we would be there in two hours.

We brought former recruits with us—as we always do—so that they could talk about their experiences. In these interactions, we have these volunteers answer our questions so that it appears as if they, too, are seeking our perspective. They talk about the huge discrepancy they encountered between their expectations and the reality of the radical group they had joined. We select former recruits whose experiences match the victim's [see “Recruitment 2.0” at bottom]. Hearing testimonies that mirror their own story, teenagers will often wise up to the formulaic recruitment they underwent. The veterans are adamant: The radical groups are not what you think they are. The recruit's dream is actually a nightmare. The shock of such revelations is brutal.

Restoring Reason

At that precise moment, the teenager starts to think for himself again. He begins his own analysis, reflecting and dissecting. Confronted at last with reality, he typically breaks down after about three hours in conversation with us and the other recruits—and runs into the arms of his parents. A complete emotional and cognitive reversal takes place at that point. The teenager enters a new phase that could be called remission. He typically reveals entire recruitment networks—information that we share with authorities.

We may think the game is now won, but it is not. Two weeks later the young recruit will typically call us back, accusing us of trying to “put him to sleep.” Meanwhile, to his support group, he will usually express astonishing ambivalence. For example, one teen explained: “One day I told myself that my recruiters were terrorists, bloody executioners who played football with severed heads, and I was wondering how they could call what they were doing a religious activity. An hour later I was sure that those who wanted to disindoctrinate me were working for the Zionists and that we needed to kill them.”

It is essential for the teen to continue to question who is telling the truth and whom to trust. This process helps to nurture a healthy state of doubt. The use of former recruits is central to our success because they introduce doubt, little by little, one personal account at a time. The survivor support groups last for six months.

Sometimes new recruits have their own doubts from the start. One woman we helped had joined the jihad in hopes of entering a world in which everyone would be like her and would love her. She believed she was embracing values of solidarity and brotherhood while stepping away from material possessions. So no wonder she was very surprised to discover her comrades in the Middle East passing around watches and ISIS T-shirts, strutting around with their Kalashnikovs and driving luxury cars. She felt intense suspicion that was difficult to explore at first, but as her doubts accumulated, her reason returned.

Today the recruiting machine is operating at full speed: five families call us every week. They represent just the tip of the iceberg. Public authorities have gone as far as they can in monitoring jihadist Web sites. Families and teachers must also confront the problem head-on and teach young people about this shadow world that exists online and how it is being used to mislead them. Too many adults have no idea of what is out there or its psychological impact. Many have no idea of what is happening with their own children until one day they wake up in hell.

Recruitment 2.0

How terror networks are evolving to attract girls

During the past few years ISIS’s recruitment techniques have advanced. They now deliberately adapt how they pitch their radical ideology to the cognitive and emotional needs of the teens they target. Recruiters get adolescents to express themselves online to understand their motivations. Then each teen receives a personalized offer according to his or her psychological “profile” (below). To a young altruist, recruiters pitch a humanitarian mission: save the children who are victims of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. Those who want to run away? Come be with people who share your values. The depressed? Fight in a great battle that will lead to the end of the world. In our experience, the following individualized approaches are particularly effective in recruiting girls.

“Abused” Profile

To a young girl who has been abused, recruiters will promise marriage to a bearded prince, armed with a Kalashnikov, and life forever covered with a niqab (a guarantee that she will never have to approach another man besides this warrior). We estimate that up to 70 percent of the girls recruited in this way are untreated rape victims.

“Guilty” Profile

In a typical scenario, a teen girl opens up online to a “friend”—a recruiter who discovers that she saw her 14-year-old brother die when she was little. Ever since then, she has believed that she will not live past 14, because she is the one who should have died on that day. The recruiter promises her an explosives belt. It will be strapped to her body, and she will die and be guaranteed to join her brother in paradise within the hour.

“Humanitarian” Profile

A third victim wants to sign up as a nurse in Burkina Faso and says so on her Facebook profile. For several weeks her page is flooded with pictures of dying children in Syria. These pictures come with a structured discourse that twists her intentions into planning terrorist attacks instead.