Abstract

Deficits in cognitive functioning and flexibility are seen following both chronic stress and modulation of endogenous cannabinoid (eCB) signaling. Here, we investigated whether alterations in eCB signaling might contribute to the cognitive impairments induced by chronic stress. Chronic stress impaired reversal learning and induced perseveratory behavior in the Morris water maze without significant effect on task acquisition. These cognitive impairments were reversed by exogenous cannabinoid administration, suggesting deficient eCB signaling underlies these phenomena. In line with this hypothesis, chronic stress downregulated CB1 receptor expression and significantly reduced the content of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonylglycerol within the hippocampus. CB1 receptor density and 2-arachidonylglycerol content were unaffected in the limbic forebrain. These data suggest that stress-induced downregulation of hippocampal eCB signaling contributes to problems in behavioral flexibility and could play a role in the development of perseveratory and ruminatory behaviors in stress-related neuropsychiatric disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Stress is a phenomenon during which an organism initiates a repertoire of physiological responses in an attempt to maintain homeostasis in the face of aversive stimuli. In the short term, these responses include mobilization of various autonomic and behavioral responses that are beneficial to the organism. However, chronic hyperactivity of neural pathways subserving these responses contributes to the pathogenesis of mental disorders such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (McEwen, 2003). This association between chronic exposure to stress and the induction of mental disorders provides an opportunity to study neural mechanisms contributing to their etiology. Furthermore, animal models such as the chronic mild or unpredictable stress model of depression have proved to be valuable tools in understanding the neurobiological relationship between stress and depression (Willner, 1997). For instance, many of the biochemical sequelae that are seen in some depressed patients are also seen in animals subjected to chronic unpredictable stress (CUS; Lopez et al, 1998). In addition to increased adrenal steroid secretion, these include increased cortical 5-HT2A receptors (Ossowska et al, 2001), decreased hippocampal 5-HT1A receptors (Lopez et al, 1998), downregulated glucocorticoid receptors (Froger et al, 2004), and increased levels of peripheral and central pro-inflammatory molecules (Grippo et al, 2003). These findings demonstrate that at least on a physiological level, the chronic unpredictable stress model is a reliable tool in examining possible biochemical changes underlying depressive states.

One neuroanatomical region sensitive to stress is the hippocampus, a region also highly associated with both affective diseases such as depression (McEwen, 2003) and with basic cognitive functioning and the regulation of learning and memory (McEwen, 2001). The hippocampus is very susceptible to stress-induced morphological and electrophysiological alterations. In particular, decrements in long-term potentiation (Alfarez et al, 2003; Pavlides et al, 2002) and dendritic atrophy and de-branching (Galea et al, 1997; Vyas et al, 2002) have been observed following long-term stress exposure. These physiological changes often correlate well with stress-induced impairments in learning, memory, and reversal learning in animals (Francis et al, 1995; de Quervain et al, 1998; Luine et al, 1994; Vasconcellos et al, 2003).

Recent evidence has accumulated suggesting that there are functional interactions between the endogenous cannabinoid (eCB) system and stress circuitry (Hill and Gorzalka, 2004; Patel et al, 2004), and furthermore that the eCB system is involved in both emotional regulation (Martin et al, 2002) and synaptic transmission in the hippocampus (Carlson et al, 2002). The association of eCB signaling and stress-related mental disorders may occur at multiple loci throughout the brain. However, the cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptor is found in abundance in the hippocampus (Herkenham et al, 1991), which, as previously mentioned, appears to be an important structure in the functional neuroanatomy of depression (McEwen, 2003). This receptor, which is located primarily on GABAergic interneurons within the hippocampus (Irving et al, 2000; Katona et al, 1999), negatively regulates adenylyl cyclase and calcium channels via coupling to Gi/o subunits, thus reducing neurotransmitter release. The CB1 receptor is responsive to exogenous cannabinoids, such as tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) from cannabis, as well as putative endogenous ligands, including 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG; Sugiura et al, 1995), which has shown to be formed in response to increased hippocampal neuronal activity (Stella et al, 1997). Hippocampal CB1 receptor activation, like stress, is associated with alterations in various cognitive tasks (Lichtman et al, 2002; Hampson and Deadwyler, 1998, 1999). In humans, cannabis consumption is known to cause impairments in learning, retention and memory retrieval (Pope et al, 2001; Solowij et al, 2002), an effect that has also been documented in animals treated with exogenous CB1 receptor ligands (Hampson and Deadwyler, 1998; Chaperon and Thiebot, 1999). These parallels suggest the possibility that eCB signaling in the hippocampus could play a functional role in the cognitive deficits seen following chronic stress.

The limbic forebrain is another neuroantomical region where convergence of stress and endocannabinoid signaling could be functionally significant. Structures in the limbic forebrain, such as the prefrontal cortex, are very sensitive to stress exposure (Mizoguchi et al, 2000) and are believed to mediate many higher order cognitive abilities such as behavioral flexibility (Miller, 2000). Like the hippocampus, limbic forebrain neurons express CB1 receptors, albeit to a lesser degree than the hippocampus (Herkenham et al, 1991). The functional role of receptors located in this region is even less well known than that of the receptors in the hippocampus. However, deficits in CB1 receptor signaling, as revealed through mice deficient in the CB1 receptor gene, result in specific impairments in cognitive flexibility as manifested through increased perseveratory behaviors (Varvel and Lichtman, 2002). Since the limbic forebrain is believed to regulate flexibility and decision making processes, it is possible that CB1 receptors located in this region play a functional role in behavioral inhibition and flexibility.

Mice deficient in the CB1 receptor gene also exhibit enhanced susceptibility to the anhedonic effects of chronic variable stress (Martin et al, 2002), suggesting that CB1 receptor activity may counteract or suppress some of the negative affective or cognitive effects induced by chronic exposure to unpredictable stress. Due to the ability of both chronic stress exposure and CB1 receptor activity to modulate cognitive function we tested the hypothesis that alterations in eCB signaling contribute to the cognitive impairments induced by chronic stress. Our data indicate that chronic, nonhabituating stress results in a decrease in functional eCB signaling within the hippocampus without affecting eCB activity in the limbic forebrain, and that the stress-induced impairment in reversal learning can be reversed by exogenous activation of CB1 receptors. These data suggest that pharmacological modulation of eCB signaling could represent a novel approach to the treatment of cognitive deficits that accompany a variety of anxiety-related neuropsychiatric disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Seventy-day-old male Long-Evans rats (300 g) housed in groups of three in triple mesh wire caging were used in this study. Colony rooms were maintained at 21°C, and on a reverse 12 h light/dark cycle, with lights off at 0900. All rats were given ad libitum access to Purina Rat Chow and tap water, except during deprivation periods of the stressing protocol (outlined below). Subjects were randomly assigned into two groups and were either subjected to 21 days of CUS (2–3 stressors a day from the following list: 30 min tube restraint; 30 min exposure to white noise/stroboscopic illumination; 5 min forced swim; 18 h food and/or water deprivation; 3 h cage rotation; 18 h social isolation), or acted as cage controls and were handled four times weekly. This chronic unpredictable stress paradigm has been successfully utilized in our laboratory (Brotto et al, 2001) to examine the effects of stress on copulatory behavior and is adapted from the chronic mild stress paradigm (see Willner, 1997). All treatments of animals were approved by the Canadian Council for Animal Care and the standards of the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of British Columbia. Testing groups were divided into subsets that were used for either behavioral analysis (n=9 or 10) or for biochemical analyses (n=4–6). Animals used for all biochemical assays were rapidly decapitated in the morning after the 21st day of stress exposure following 12 h of overnight social isolation. Brains were removed and the hippocampus and limbic forebrain (all tissue rostral to the amygdala, excluding the olfactory bulbs) were sectioned and frozen in liquid nitrogen within 5 min of decapitation and stored at −80°C until analysis. Trunk blood was also collected upon decapitation for measurement of plasma corticosterone.

Tissue Preparation for Endocannabinoid Quantification

Brain tissue samples were subjected to a lipid extraction process exactly as described previously (Patel et al, 2003). The content of both 2-AG and the other major eCB ligand, anandamide (AEA; Devane et al, 1992) within lipid extracts were determined using isotope-dilution liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry as described previously (Patel et al, 2003).

CB1 Receptor Binding Assays and Western Blots

To make membranes, dissected brain sections were homogenized in 5 ml TME buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 3 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4 with Tris base) using a Dounce homogenizer. Membranes were centrifuged at 17 500g for 20 min, and the resulting pellet was resuspended by homogenizing in 2–2.5 ml TME buffer+1 mM sodium orthovanadate. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

CB1 receptor binding assays were performed using a Multiscreen Filtration System with Durapore 1.2-μM filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Incubations (total volume=0.2 ml) were performed with TME buffer containing 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (TME/BSA). Membranes (10 μg protein per incubate) were added to the wells containing 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, or 2.5 nM 3H-CP 55 940. In total, 10 μM Δ9-THC was used to determine nonspecific binding.

For Western blotting procedures, all membranes were made to a 3 mg/ml final concentration in TME buffer. Laemmli loading buffer (4 ×) was added to each sample, and samples denatured at 65°C for 5 min. Protein samples were loaded onto a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, separated by electrophoresis, and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Nonspecific membrane binding was blocked at 4°C with an overnight incubation in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.2% Tween-20 (PBST) and 2% milk. Primary anti-rCB1 antibody was diluted 1:300 in PBST/milk, and incubated with the membrane overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (diluted 1:3000 in PBST/milk) for 45 min at room temperature.

Corticosterone Assays

Upon collection of trunk blood, samples were stored overnight at 4°C and centrifuged the following morning at 10g for 10 min. Plasma was removed and centrifuged again at 10g for 10 min. Bound plus free serum corticosterone was measured through radioimmunoassay, using a previously validated method (Weinberg and Bezio, 1987). Antiserum was obtained from Immunocorp Montreal, Canada and tracer was obtained from Mandel Scientific, Guelph, Canada. Dextran coated charcoal was used to absorb and precipitate free steroids after incubation.

Behavioral Analysis

The Morris water maze (MWM) used in this experiment was a large, circular pool (193 cm diameter) that was filled to a depth of 70 cm with water (22°C) that was made opaque through the addition of nontoxic white paint (Washable Dry Temp, Palmer Paint Products, Troy, MI, USA). The platform was a cylindrical jar (17 × 8.5 cm2) that had a square wire mesh platform on top that was submerged 3 cm below the surface of the water. Distinctive distal visual cues surrounded the pool and remained in place for the duration of the experiment. A computer-based automated tracking system (HVS Image, Hampton, UK) was used to calculate the swim speed and escape latencies (the time each subject required to locate the hidden platform after being released) of each subject.

Testing in the MWM began on day 16 of the stress regimen. All testing in the MWM occurred in the morning prior to the induction of any stressors that day. Animals were trained in a standard protocol for acquisition and reversal learning that has been previously described (Varvel and Lichtman, 2002). Briefly, rats were trained with five acquisition sessions that consisted of four trials per day with an intertrial interval of 30 s. During the acquisition period, the hidden platform remained in the same fixed position, which was randomly determined for each rat. On day 22, after five sessions of acquisition training, all rats were subjected to a reversal test in which the platform was moved to the opposite side of the tank, but all other testing factors remained constant. For reversal testing, subjects in both the stress and control groups were divided up into two subgroups: administration of vehicle (1:1:18 Tween 80: dimethyl sulfoxide/saline) or 10 μg/kg HU-210 (Tocris-Cookson, Bristol, UK). Subjects received an injection of either vehicle or HU-210 30 min prior to the first of four reversal trials. As in the acquisition task, all rats were released from the same point, but the platform was moved to the opposite quadrant of the pool. Escape latencies and amount of time spent in each quadrant of the pool were analyzed.

Statistics

Comparison of the effects of CUS on CB1 receptor binding and protein expression, as well as on eCB synthesis and plasma corticosterone values, were carried out using an independent t-test. Behavioral data in the MWM was analyzed using a two-factor analysis of variance, and post hoc analysis performed using a Tukey HSD test. Significance was established against an alpha level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Biochemical Changes in the eCB System Induced by Chronic Stress

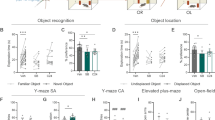

Animals exposed to 21 days of CUS exhibited increased concentrations of plasma corticosterone (t(8)=−3.2, p<0.05) when compared to nonstressed animals (stressed animals: 17.3±3.4 dg/ml; control animals: 3.4±1.1 dg/ml; mean±SEM), indicating that the paradigm used elicited a nonhabituating stress response. Following CUS, rats exhibited a 50% reduction in CB1 receptor protein expression in the hippocampus (t(9)=2.5, p<0.05) compared to nonstressed controls (Figure 1a). In addition, stressed animals exhibited a 40% reduction in the Bmax of CB1 receptor binding (t(22)=3.1, p<0.01) without a change in the KD of the receptor for [3H]CP55940 (t(22)=1.2, NS) (Table 1). In the limbic forebrain, no differences in CB1 receptor protein (t(6)=0.4, NS), Bmax (t(22)=0.3, NS) or KD for [3H]CP55940 (t(22)=0.1, NS) were observed between CUS-treated rats and cage controls (Figure 1b and Table 1).

Effect of 21 days of chronic stress on CB1 receptor protein expression as determined through Western blot analysis in the hippocampus (a) and limbic forebrain (b). Values are denoted as means±SEM of band density (in arbitrary units). Representative Western blot pairs are seen next to the graphs. *Significantly different from control (p<0.05) (n=4/group).

Stressed animals exhibited a 40% reduction in 2-AG content (t(7)=4.9, p<0.005), AEA content was not significantly altered (t(8)=2.0, NS) (Figure 2a). In the limbic forebrain, there were no differences in 2-AG (t(8)=0.3, NS) or AEA (t(8)=1.2, NS) content between CUS-exposed rats and cage controls (Figure 2b).

Behavioral Changes Induced by Chronic Stress and Their Reversal Following Cannabinoid Agonist Administration

Behavioral testing in the MWM task began after 16 days of exposure to CUS. Stressed animals exhibited no cognitive deficits during the acquisition phase of the task in which the animals learned the location of a platform that provided an escape from the water (F(1, 6)=0.3, NS). Daily escape latency times during acquisition training can be viewed in Figure 3a. However, during reversal trials, in which the platform was placed on the opposite quadrant of the water maze, stressed animals exhibited a deficit in learning the location of the new platform (F(3, 34)=2.4, p<0.05). This deficit was not accompanied by any significant changes in swim speed (F(3, 34)=1.8, NS) (data not shown). Post hoc analysis indicated that there were no significant differences in escape latency in the first two trials of reversal learning, but on the third and fourth trials the stressed animals were significantly impaired compared to the nonstressed group (p<0.05). Analysis of the percent time spent in each quadrant during the reversal trials indicated that the escape latency deficit seen in the stressed animals was paralleled by an increased percentage of time spent in the quadrant in which the platform had originally been placed (F(3, 34)=3.4, p<0.01). Post hoc analysis revealed that stressed animals spent significantly more time in the trained quadrant in trials 3 and 4 (p<0.05). Exogenous administration of 10 μg/kg of the CB1 receptor agonist HU-210, prior to the reversal task, completely blocked the deficits in reversal learning and perseveratory behavior seen following CUS (p<0.05; Figure 3b and c).

Effect of chronic stress and subsequent exogenous cannabinoid treatment on acquisition and reversal tasks in the Morris water maze. (a) CUS exposure did not have an effect on escape latency during platform acquisition in the MWM (n=18/group). (b) Chronic stress (S) impaired reversal learning in the MWM as relative to nonstressed (NS) animals. Pretreatment of rats with 10 μg/kg HU-210 (CB), a selective and potent CB1 receptor agonist, prevented the deficit in reversal learning seen in vehicle-treated (V) stressed animals (V) (n=9 or 10/group). (c) Stressed animals were found to spend a higher proportion of time in the training quadrant, an effect that was attenuated by pretreatment with HU-210. *Significantly different (p<0.05) from all other groups (n=9 or 10/group).

DISCUSSION

These experiments demonstrate that exposure of rats to CUS for 21 days is associated with robust reductions in both 2-AG content and CB1 receptor density within the hippocampus, and the induction of perseveratory behavior in the MWM. Rats that had been subjected to CUS exhibited difficulties in learning a new platform location when it was shifted to the opposite side of the maze. This increase in escape latency was paralleled by an increase in the percent of time spent in the initial training quadrant, indicating that the stressed animals were perseverating. The cognitive impairments induced by CUS were strikingly similar to those observed in CB1−/− mice, which also show impairments in extinction and perseveratory behavior in a variety of cognitive tasks including the MWM (Varvel and Lichtman, 2002), suggesting that the cognitive impairments induced by chronic stress could be a consequence of deficient eCB signaling. This enhanced perseveratory behavior was attenuated by pharmacological enhancement of CB1 receptor activity, consistent with mediation by deficient eCB signaling. This suggests that a physiological response to CUS is a significant attenuation of eCB signaling in the hippocampus, which in turn could contribute to the cognitive impairments induced by chronic stress. However, this suggestion remains speculative until it is verified through pharmacological antagonism of the eCB system and other experiments are carried out to address the causal nature of the relationship. Chronic stress was found to have no effect on either CB1 receptor binding or synthesis of the endogenous ligands in the limbic forebrain, another region that is highly activated during environmental stress (Bubser and Deutch, 1999).

In the present studies, exposure to CUS did not influence acquisition of learning the MWM. This finding was surprising, as exposure to chronic stressors is typically shown to impair spatial learning (Luine et al, 1994). However, many of these studies utilized chronic, homotypic stress paradigms (eg chronic restraint), which are known to induce dendritic atrophy in the hippocampus not seen in animals exposed to a variable stress paradigm such as the one utilized here (Vyas et al, 2002). However, it should be noted that there are discrepancies in the literature on the effects of chronic stress on spatial learning. While many studies suggest a decrement occurs (Vasconcellos et al, 2003; Touyarot et al, 2004; Luine et al, 1994), others suggest that there may be an enhancement under some conditions (Bartolomucci et al, 2002). Clearly, the mechanisms contributing to the effects of stress on cognitive functioning require further investigation.

It is interesting that chronic stress resulted in both downregulation of CB1 receptors and a decrease in 2-AG content in the hippocampus. Several studies have demonstrated that chronic treatment of rats (Breivogel et al, 1999) and mice (Sim-Selley and Martin, 2002) with CB1 receptor agonists results in downregulation of the CB1 receptor. However, these studies were conducted using high doses of agonists with long biological half-lives. In contrast, Romero et al (1995) demonstrated that i.p. administration of anandamide once daily for 5 days resulted in a significant increase in CB1 receptor density in the hippocampus with no effect in the limbic forebrain. Thus, these studies provide evidence that moderate activation of CB1 receptor activity can result in its upregulation in the hippocampus. By analogy, it is possible that the stress-induced decrease in hippocampal eCB content drives the decrease in CB1 receptor density due to withdrawal of a trophic factor for CB1 receptor expression, in this case, its ligand.

Alternatively, the change in CB1 receptor density and eCB content could occur independently, both driven by the physiologic changes that accompany stress but not dependent on each other. Interestingly, it has been suggested that glucocorticoids (GC) exert negative regulation over CB1 receptor transcription (Mailleux and Vanderhaeghen, 1993). This idea was supported here as this stress protocol induced both elevated GC levels and reduced hippocampal CB1 receptor density. However, the lack of downregulation of CB1 receptors in the limbic forebrain suggests that the mechanisms involved in regulation of CB1 receptor density in the hippocampus must include more than GC changes. Di et al (2003) have recently shown that GCs stimulate eCB synthesis through a nongenomic, fast-acting mechanism, which contrasts with the present findings in the hippocampus and suggests that the modulation of eCB content by chronic exposure to unpredictable stress is not solely GC mediated and likely brain region specific.

It is possible that increased leptin levels could be driving the decrease in eCB content in the hippocampus seen in this study. The satiety peptide leptin is known to decrease brain eCB content (Di Marzo et al, 2001). Since leptin production is elevated following chronic unpredictable stress (Gamaro et al, 2003), it is possible that increased leptin levels could be driving the decrease in eCB content in the hippocampus seen in this study. It is interesting in light of this argument that rats given free access to a highly palatable food for 10 weeks, which significantly elevates plasma leptin concentrations, exhibit a 30–50% decrease in CB1 receptor density in the hippocampus (Harrold et al, 2002). It is also possible that changes in other neurotransmitter systems could be mediating the changes in eCB levels; however, due to the fact that stress stimulates excitatory transmission in the hippocampus (McEwen and Magarinos, 1997), one would actually expect an increase and not a decrease in eCB levels (Stella et al, 1997). At present, it is difficult to speculate on the exact mechanism of action of these physiological changes, given that the biosynthetic pathways of eCB synthesis are not well understood.

A growing body of evidence suggests that eCB activity plays a crucial role in cognitive processes that require inhibition of a previously learned behavior, such as extinction or reversal learning. Genetic deletion of the CB1 receptor gene results in animals that exhibit perseveration during reversal learning (Varvel and Lichtman, 2002) or an inability to extinguish aversive memories in fear conditioning paradigms (Marsicano et al, 2002). This study complements these previous data by showing that deficits in flexibility are apparent when eCB signaling is blunted in the hippocampus, suggesting that deficits in eCB signaling in areas of the limbic forebrain, such as the prefrontal cortex, are not required for inhibition of a behavioral strategy. This does not preclude the idea that forebrain structures play a fundamental role in the manifestation of cognitive flexibility, but suggests that the ability of eCB signaling to affect this behavior is likely mediated through its actions in the hippocampus. It is known that glutamatergic projections originating from the ventral subiculum of the hippocampus terminate in the prelimbic region of the prefrontal cortex (PFC; Carr and Seasack, 1996), forming a connection which could subserve such an interaction. Given that CB1 receptor activation inhibits hippocampal GABA release (Katona et al, 1999), our data suggest that CUS could increase local GABAergic tone and thus decrease the activity of this hippocampal–PFC pathway. Thus, modulation of prefrontal cortical activity could ultimately mediate the disturbance in higher order cognitive tasks that was seen here; however, this hypothesis requires further investigation.

Aside from demonstrating that deficits in cognitive flexibility are associated with attenuated endocannabinoid signaling in the hippocampus, this study also demonstrates that these behavioral changes, previously only attained through genetic manipulation of mice or pharmacological blockade of the CB1 receptor (Varvel and Lichtman, 2002; Marsicano et al, 2002), can be induced through environmental manipulations. Recently, it was shown that enriched environmental exposure results in 10-fold elevations in hippocampal eCB content (Wolf and Matzinger, 2003), which together with the data presented here suggest that hippocampal eCB signaling is vulnerable to environmental changes, becoming blunted during periods of prolonged stress and elevated following enrichment. Owing to the association between affective disease and stress, and the fact that the CUS paradigms have been shown to model many of the neurochemical disturbances seen in depression (Lopez et al, 1998; Ossowska et al, 2001; Willner, 1997), these findings also suggest that the eCB system may be another system that could be disturbed in depression, and thus play a role in the manifestation of some of the symptoms of affective disease.

Several research groups have suggested that eCB signaling in the hippocampus plays a functional role in the forgetting process (Terranova et al, 1996; Hampson and Deadwyler, 1998; Varvel and Lichtman, 2002), an idea supported by our findings that blunted hippocampal eCB signaling was associated with deficits in behavioral flexibility. Interestingly, many stress-related mental diseases, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, are characterized by problems with forgetting and behavioral flexibility that are manifested as pathological tendencies to ruminate or perseverate on negative information (Bagby et al, 1999; Gold and Chrousos, 2002; Heresco-Levy et al, 2002; King, 2002). Considering the present evidence and previous evidence from other laboratories, one may postulate that stress-induced deficits in cognitive flexibility are mediated in part by stress-induced reductions in hippocampal eCB signaling. If stress-induced attenuation of eCB signaling is involved in the manifestation of perseveratory and ruminatory behavior, then pharmacological manipulation of this system could prove to be a novel approach to treatment of these cognitive symptoms.

References

Alfarez DN, Joels M, Krugers HJ (2003). Chronic unpredictable stress impairs long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal CA1 area and dentate gyrus in vitro. Eur J Neurosci 17: 1928–1934.

Bagby RM, Rector NA, Segal ZW, Joffe RT, Levitt AJ, Kennedy SH et al (1999). Rumination and distraction in major depression: assessing responses to pharmacological treatment. J Affect Disord 55: 225–229.

Bartolomucci A, de Biurrun G, Czeh B, van Kampen M, Fuchs E (2002). Selective enhancement of spatial learning under chronic psychosocial stress. Eur J Neurosci 15: 1863–1866.

Breivogel CS, Childers SR, Deadwyler SA, Hampson RE, Vogt LJ, Sim-Selly LJ (1999). Chronic Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol treatment produces a time-dependent loss of cannabinoid receptors and cannabinoid receptor-activated G proteins in rat brain. J Neurochem 73: 2447–2459.

Brotto LA, Gorzalka BB, LaMarre AK (2001). Melatonin protects against the effects of chronic stress on sexual behavior in male rats. Neuroreport 12: 3465–3469.

Bubser M, Deutch AY (1999). Stress induces fos expression in neurons of the thalamic paraventricular nucleus that innervate limbic forebrain sites. Synapse 32: 13–22.

Carlson G, Wang Y, Alger BE (2002). Endocannabinoids facilitate the induction of LTP in the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci 5: 723–724.

Carr DB, Seasack SR (1996). Hippocampal afferents to the rat prefrontal cortex: synaptic targets and relation to dopamine terminals. J Comp Neurol 369: 1–15.

Chaperon F, Thiebot MH (1999). Behavioral effects of cannabinoid agents in animals. Crit Rev Neurobiol 13: 243–281.

de Quervain DG, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL (1998). Stress and glucocorticoids impair retrieval of long term memory. Nature 394: 787–790.

Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G et al (1992). Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 258: 1946–1949.

Di S, Malcher-Lopes R, Halmos KC, Tasker JG (2003). Non-genomic glucocorticoid inhibition via endocannabinoid release in the hypothalamus: a fast feedback mechanism. J Neurosci 23: 4850–4857.

Di Marzo V, Goparaju SK, Wang L, Liu J, Batkai S, Jarai Z et al (2001). Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake. Nature 410: 822–825.

Francis DD, Zaharia MD, Shanks N, Anisman H (1995). Stress-induced disturbances in Morris water maze performance: interstrain variability. Physiol Behav 58: 57–65.

Froger N, Palazzo E, Boni C, Hanoun N, Saurini F, Joubert C et al (2004). Neurochemical and behavioral alterations in glucocorticoid receptor-impaired transgenic mice after chronic mild stress. J Neurosci 24: 2787–2796.

Galea LA, McEwen BS, Tanapat P, Deak T, Spencer RL, Dhabhar FS (1997). Sex differences in dendritic atrophy of CA3 pyramidal neurons in response to chronic restraint stress. Neuroscience 81: 689–697.

Gamaro GD, Prediger ME, Lopes JB, Dalmaz C (2003). Interactions between estradiol replacement and chronic stress on feeding behavior and on serum leptin. Pharmacol Bioc Behav 76: 327–333.

Gold PW, Chrousos GP (2002). Organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in melancholic and atypical depression: high vs low CRH/NE states. Mol Psychiatry 7: 254–275.

Grippo AJ, Francis J, Beltz TG, Felder RB, Johnson A (2003). Elevated cytokines in the chronic mild stress animal model of depression. Soc Neurosci Abstr 927: 10.

Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA (1998). Role of cannabinoid receptors in memory storage. Neurobiol Dis 5: 474–482.

Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA (1999). Cannabinoids, hippocampal function and memory. Life Sci 65: 715–723.

Harrold JA, Elliott JC, King PJ, Widdowson PS, Williams G (2002). Down-regulation of cannabinoid-1 (CB-1) receptors in specific extrahypothalamic regions of rats with dietary obesity: a role for endogenous cannabinoids in driving appetite for palatable food? Brain Res 952: 232–238.

Heresco-Levy U, Kremer I, Javitt DC, Goichman R, Reshef A, Blanaru M et al (2002). Pilot-controlled trial of D-cycloserine for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 5: 301–307.

Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC (1991). Characterization and localization of cannabinoid receptors in the rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. J Neurosci 11: 563–583.

Hill MN, Gorzalka BB (2004). Enhancement of the anxiety-like response to the cannabinoid receptor agonist HU-210 following chronic stress. Eur J Pharmacol 24: 291–295.

Irving AJ, Coutts AA, Harvey J, Rae MJ, Mackie K, Bewick GS et al (2000). Functional expression of cell surface cannabinoid CB(1) receptors on presynaptic inhibitory terminals in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience 98: 253–262.

Katona I, Sperlagh B, Sik A, Kafalvi A, Vizi ES, Mackie K et al (1999). Presynaptically located CB1 cannabinoid receptors regulate GABA release from axon terminals of specific hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci 19: 4544–4558.

King NS (2002). Perseveration of traumatic re-experiencing in PTSD; a cautionary note regarding exposure based psychological treatments for PTSD when head injury and dysexecutive impairment are also present. Brain Injury 16: 65–74.

Lichtman AH, Varvel SA, Martin BR (2002). Endocannabinoids in cognition and dependence. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 66: 269–285.

Lopez JF, Chalmers DT, Little KY, Watson SJ (1998). Regulation of serotonin1A, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid receptor in rat and human hippocampus: implications for the neurobiology of depression. Biol Psychiatry 43: 547–573.

Luine V, Villegas M, Martinez C, McEwen BS (1994). Repeated stress causes reverible impairments of spatial memory performance. Brain Res 639: 167–170.

Mailleux P, Vanderhaeghen JJ (1993). Glucocorticoid regulation of cannabinoid receptor messenger mRNA levels in the rat caudate-putamen: an in-situ hybridization study. Neurosci Lett 156: 51–53.

Marsicano G, Wotjak CT, Azad SC, Bisogno T, Rammes G, Cascio MG et al (2002). The endogenous cannabinoid system controls extinction of aversive memories. Nature 418: 530–534.

Martin M, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Maldonado R, Valverde O (2002). Involvement of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in emotional behavior. Psychopharmacology 159: 379–387.

McEwen BS (2001). Plasticity of the hippocampus: adaptation to chronic stress and allostatic load. Ann NY Acad Sci 933: 265–277.

McEwen BS (2003). Mood disorders and allostatic load. Biol Psychiatry 54: 200–207.

McEwen BS, Magarinos AM (1997). Stress effects on morphology and function of the hippocampus. Ann NY Acad Sci 821: 271–284.

Miller EK (2000). The prefrontal cortex and cognitive control. Nat Rev Neurosci 1: 59–65.

Mizoguchi K, Yuzurihara M, Ishige A, Sasaki H, Chui D-H, Tabira T (2000). Chronic stress induces impairment of spatial working memory because of prefrontal dopaminergic dysfunction. J Neurosci 20: 1568–1574.

Ossowska G, Nowa G, Kata R, Klenk-Majewska B, Danilczuk Z, Zebrowski-Lupina I (2001). Brain monoamine receptors in a chronic unpredictable stress model in rats. J Neural Transm 108: 311–319.

Patel S, Cravatt BF, Hillard CJ (2004). Synergistic interactions between cannabinoids and environmental stress in the activation of the central amygdalae. Neuropsychopharmacology, doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300535.

Patel S, Rademacher DJ, Hillard CJ (2003). Differential regulation of the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-arachidonylglycerol within the limbic forebrain by dopamine receptor activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306: 880–888.

Pavlides C, Nivon LG, McEwen BS (2002). Effects of chronic stress on hippocampal long-term potentiation. Hippocampus 12: 245–257.

Pope Jr HG, Gruber AJ, Hudson JI, Huestis MA, Yurgelun-Todd D (2001). Neuropsychological performance in long-term cannabis users. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58: 909–915.

Romero J, Garcia L, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ, Cebeira M, Ramos JA (1995). Changes in rat brain cannabinoid binding sites after acute or chronic exposure to their endogenous agonist, anandamide, or to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 51: 731–737.

Sim-Selley LJ, Martin BR (2002). Effect of chronic administration of R-(+)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3-[(morpholinyl)methyl]pyrrolo[1,2,3-de]-1,4-benzoxazinyl]-(1-naphthalenyl)methanone mesylate (WIN55212-2) or Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol on cannabinoid receptor adaptation in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303: 36–44.

Solowij N, Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Babor T, Kadden R, Miller M et al (2002). Cognitive functioning of long term heavy cannabis users seeking treatment. JAMA 287: 1123–1131.

Stella N, Schweitzer P, Piomelli D (1997). A second endogenous cannabinoid that modulates long-term potentiation. Nature 388: 773–778.

Sugiura T, Kondo S, Sukagawa A, Nakane S, Shinoda A, Itoh K et al (1995). 2-Arachidonylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in the brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 215: 89–97.

Terranova JP, Storme JJ, Lafon N, Perio A, Rinaldi-Carmona M, Le Fur G et al. (1996). Improvement of memory in rodents by the selective CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonist, SR 141716. Psychopharmacology 126: 165–172.

Touyarot K, Venero C, Sandi C (2004). Spatial learning impairment induced by chronic stress is related to individual differences in novelty reactivity: search for neurobiological correlates. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29: 290–305.

Varvel SA, Lichtman AH (2002). Evaluation of CB1 receptor knockout mice in the Morris water maze. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 301: 915–924.

Vasconcellos AP, Tabajara AS, Ferrari C, Rocha E, Dalmaz C (2003). Effect of chronic stress on spatial memory in rats is attenuated by lithium treatment. Physiol Behav 79: 143–149.

Vyas A, Mitra R, Shankaranarayana Rao BS, Chattarji S (2002). Chronic stress induces contrasting patterns of dendritic remodeling hippocampal and amygdaloid neurons. J Neurosci 22: 6810–6818.

Weinberg J, Bezio S (1987). Alcohol-induced changes in pituitary–adrenal activity during pregnancy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 11: 274–280.

Willner P (1997). Validity, reliability and utility of the chronic mild stress model of depression: a 10 year review and evaluation. Psychopharmacology 134: 319–329.

Wolf S, Matzinger P (2003). Relax—endogenous cannabinoids in enriched mice. 13th Annual Symposium on the Cannabinoids, p 89.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH Grant R01-DA016967 and an Independent Investigator Award from NARSAD to CJH; a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) grant to BBG; an NSERC postgraduate scholarship and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) Research Training Award to MNH; an NIH-NRSA grant (F30 DA15575) to SP; an NIH-NRSA grant (F32 DA16510) to DJR. We like to thank Maric Tse, Indy Gill, Eda Karacabeyli and Wayne Yu for their technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hill, M., Patel, S., Carrier, E. et al. Downregulation of Endocannabinoid Signaling in the Hippocampus Following Chronic Unpredictable Stress. Neuropsychopharmacol 30, 508–515 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300601

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300601

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

How depression and antidepressant drugs affect endocannabinoid system?—review of clinical and preclinical studies

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2024)

-

Role of mesolimbic cannabinoid receptor 1 in stress-driven increases in cocaine self-administration in male rats

Neuropsychopharmacology (2023)

-

The antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of cannabinoids in chronic unpredictable stress: a preclinical systematic review and meta-analysis

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

Chronic mild stress paradigm as a rat model of depression: facts, artifacts, and future perspectives

Psychopharmacology (2022)

-

The effects of FAAH inhibition on the neural basis of anxiety-related processing in healthy male subjects: a randomized clinical trial

Neuropsychopharmacology (2021)