Abstract

Light fields at terahertz and mid-infrared frequencies allow for the direct excitation of collective modes in condensed matter, which can be driven to large amplitudes. For example, excitation of the crystal lattice1,2 has been shown to stimulate insulator–metal transitions3,4, melt magnetic order5,6 or enhance superconductivity7,8,9. Here, we generalize these ideas and explore the simultaneous excitation of more than one lattice mode, which are driven with controlled relative phases. This nonlinear mode mixing drives rotations as well as displacements of the crystal-field atoms, mimicking the application of a magnetic field and resulting in the excitation of spin precession in the rare-earth orthoferrite ErFeO3. Coherent control of lattice rotations may become applicable to other interesting problems in materials research—for example, as a way to affect the topology of electronic phases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

ErFeO3 is an antiferromagnetic insulator that crystallizes in an orthorhombically distorted perovskite structure, as shown in Fig. 1a (space group: Pbnm). Because of the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction, the spins are canted and result in a small ferromagnetic moment (saturated by a 7.5 mT field10) along the c axis (Fig. 1b).

a, Crystal structure of ErFeO3, an orthorhombically distorted perovskite (Pbnm). b, Magnetic ordering. The spins of the iron ions order antiferromagnetically along a. Owing to the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction, a canting is induced out of the ab plane, resulting in a small ferromagnetic component along c. c, Eigenvectors of the highest-frequency phonons excited by the pump pulse. Singly degenerate infrared-active Bua and Bub phonons (calculated eigenvectors for ErFeO3). d, The motion of the ions results in an elliptically polarized phononic field due to the non-degenerate nature of the excited infrared-active phonons (16.17 THz and 17.03 THz). All Fe–O layers in the unit cell behave in a similar fashion.

In our experiments, femtosecond mid-infrared pulses at 20 THz frequency were tuned to drive the in-plane Bua and Bub phonons11. The eigenvectors of these modes are shown in Fig. 1c. The pump was linearly polarized and aligned at variable angles with respect to the a and b crystallographic axes. Due to the orthorhombic distortion in ErFeO3, the infrared-active modes along the two axes exhibit different eigenfrequencies and oscillator strengths. As a consequence, even when the modes are excited simultaneously (for example, with the light polarization at a 45° angle from either crystal axes), the two modes start with a nonzero relative phase, and advance in time at different rates. Hence, the total lattice polarization inside the material is elliptical (Fig. 1d). This is interesting, as coherent atomic loops12 can break time-reversal symmetry and stimulate a new class of opto-magnetic phenomena, which are independent of equilibrium multiferroicity13,14,15.

These considerations are validated here by mid-infrared pump, optical probe experiments performed at 100 K. The Faraday rotation of a linearly polarized near-infrared pulse (800-nm wavelength) was measured as a function of time delay after direct lattice excitation. As shown in Fig. 2a, the polarization of the probe was found to oscillate in time, revealing the coherent excitation of a number of Raman-active modes (Fig. 2b). These include Raman phonons of A1g + B1g and B1g symmetry (3.36 THz and 4.85 THz, respectively).

a, Pump-induced changes in the polarization of the probe as a function of pump–probe delay. The slow-varying component has been subtracted. Multi-component fast oscillations (grey) can be filtered out by a low-pass filter (1.5 THz cutoff) to reveal the slow oscillation associated with the magnon (red). The sample was kept at 100 K while the fluence of the pump pulse was 17.6 mJ cm−2. b, Power spectrum of the oscillatory signal. The three peaks correspond to: 0.75 THz, quasi-antiferromagnetic (q-AFM) magnon (red), and 3.36 THz and 4.85 THz, Raman phonons of symmetry A1g + B1g (orange) and B1g (blue), respectively. c, Cartoon of the spin motion (S1 and S2) for the q-AFM mode. The small ferromagnetic component along the c axis (green) oscillates in amplitude at the magnon frequency.

Strikingly, we also observed the excitation of a coherent quasi-antiferromagnetic magnetic mode (q-AFM, 0.75 THz) (ref. 16), associated with a modulation of the ferromagnetic moment along the c axis (Fig. 2c)17.

Figure 3a shows the pump-wavelength-dependent amplitude of this mode, plotted with the reflectivity of the material and the real part of the dielectric function. The magnitude of the magnetic mode was larger for wavelengths near the zero-crossing of the dielectric function (19.6 THz). The corresponding lattice-induced magnetization was estimated by normalizing the raw data against the penetration-depth mismatch between the pump and the probe (Fig. 3b, see Supplementary Section 6). The maximum precession amplitude was approximately 1.5% of the saturation magnetization. Also, as shown in Fig. 3c, this amplitude scaled quadratically with the electric field of the pump, indicating a response proportional to the product of two phonon coordinates.

a, Pump wavelength dependence of the measured Faraday rotation and real part of the dielectric function. The blue dots are the values of the coherent magnon amplitude derived from a fit of the oscillations and extrapolated to zero time delay. The solid grey line is a Lorentzian fit intended as a guide to the eye. The solid red curve is the static sample reflectivity measured by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The dashed line is a fit to the measured reflectivity. The real part of the dielectric function ɛ1 (solid purple line) is retrieved from the reflectivity via a Kramers–Krönig consistent fit. The dotted black line indicates the zero-crossing of ɛ1. All the measurements were made at a constant fluence of 20 mJ cm−2. b, Pump wavelength dependence of the magnetization change. To estimate the absolute change of magnetization we corrected the data of Fig. 1a for the penetration-depth mismatch between the pump and the probe (see Supplementary Section 6). c, Amplitude dependence on the pump field measured at 19.5 THz. The magnon amplitude scales quadratically with the pump electric field—linearly with the fluence. Indeed, the electric field (E) of a pulse can be estimated from its duration (Δτ) and the fluence (F) at the sample position. The connecting formula is  , where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity and c is the speed of light. d, Pump polarization dependence. Here are presented (light colours) the measured oscillations for different pump polarizations. The darker lines show the same data after application of a numerical low-pass filter (1.5 THz cutoff) to emphasize the magnon (when present). Upper curve: pump polarization directed along one crystallographic axis. Only the Raman-active phonon oscillations (light blue) can be detected, while the magnon vanishes (dark blue). Middle curve: pump polarization in between a and b. The two infrared-active phonons are excited with the same initial positive phase (Bub + Bua). In addition to the Raman phonons, the magnon appears (dark red). Lower curve: pump polarization rotated by 90°, in between −a and b. The two infrared-active phonons are excited with phases of opposite signs (Bub − Bua). The magnon experiences a π phase shift (dark orange). e, External magnetic field dependence. The phase of the magnon does not depend on the initial orientation of the magnetic order.

, where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity and c is the speed of light. d, Pump polarization dependence. Here are presented (light colours) the measured oscillations for different pump polarizations. The darker lines show the same data after application of a numerical low-pass filter (1.5 THz cutoff) to emphasize the magnon (when present). Upper curve: pump polarization directed along one crystallographic axis. Only the Raman-active phonon oscillations (light blue) can be detected, while the magnon vanishes (dark blue). Middle curve: pump polarization in between a and b. The two infrared-active phonons are excited with the same initial positive phase (Bub + Bua). In addition to the Raman phonons, the magnon appears (dark red). Lower curve: pump polarization rotated by 90°, in between −a and b. The two infrared-active phonons are excited with phases of opposite signs (Bub − Bua). The magnon experiences a π phase shift (dark orange). e, External magnetic field dependence. The phase of the magnon does not depend on the initial orientation of the magnetic order.

The coherent magnon oscillations were observed only for pump pulses polarized at +45° or −45°, in between the crystallographic a and b axes (Fig. 3d, red and orange lines). In contrast, when the pump electric field was directed along either one of the two crystallographic axes, only Raman phonons were detected (Fig. 3d, blue line). Hence, the magnetic response could be driven only when two different orthogonal phonon modes were excited. Moreover, the phase of the magnon oscillations switched sign when the pump polarization was rotated from +45° to −45°, revealing a dependence on the relative phase of the two driven phonons (Fig. 3d, red and orange lines).

Finally, the phase of the measured magnon oscillations did not change when the static magnetization was reversed (Fig. 3e), indicating that their direction was independent of the initial canting of the spins.

Let us consider the physical situation depicted in Fig. 1d, where the oxygen ions perform rotational motions. Qualitatively, these rotations are expected to modify the crystal field felt by the high-spin Fe3+ ion at the centre of the octahedron. This effect mixes the ground state t2g3eg2 electronic wavefunction18 at each Fe3+ ion with excited states, for which spin–orbit coupling is enhanced. Thus, the moving ions promptly perturb the angular momentum of the t2g3eg2 state, triggering a magnetic excitation. This effect has some analogy with the case of electronic Raman excitation of magnons19,20,21, in which visible light fields mix the ground state wavefunction with that of excited state orbitals.

Our results can be described by considering an effective Hamiltonian of the form Heff = iαabcQuaQub∗Mc. In this expression, αabc is the magneto-elastic susceptibility, antisymmetric over the first pair of indices αabc = −αbac, Qua and Qub∗ are the phonon eigenvectors and Mc is the static magnetization. Hence, the circularly polarized lattice motion behaves as an effective magnetic field [−∂Heff/∂Mc] = −iαabcQuaQub∗ directed perpendicular to the rotation plane (the ab plane in the present case, Fig. 1d). Moreover, the sign of the field depends on the rotation direction of the ions.

These arguments, and especially the directionality of the effective field as perpendicular to the rotation plane of the atoms, are validated by temperature-dependent measurements (Fig. 4).

a, Spin reorientation transition. In ErFeO3 for 87 K < T < 96 K, a change of easy axis takes place. As a consequence the spins (red) and the resulting ferromagnetic moment (green) rotate continuously from the c axis to the a axis. The spin configuration varies from Γ4(GxFz, magnetic space group: Pb′n′m; ref. 30) for T > TSRT to Γ2(GzFx, magnetic space group: Pbn′m′; ref. 30) for temperatures below the spin reorientation transition. b, Cartoon of the spin motion for the quasi-ferromagnetic mode. The small ferromagnetic component precesses around the a axis (light blue), resulting in a modulation of the magnetization along the b and c axes (purple arrows). c, Temperature dependence of the quasi-ferromagnetic (q-FM) magnon frequency. Owing to the spin reorientation transition the geometry of our experiment changes and we are able to excite exclusively the other magnon branch. The measured frequencies and the data from the literature (adapted from ref. 22) are in excellent agreement. The time-dependent traces for each temperature are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

When cooling below 96 K, ErFeO3 undergoes a spin reorientation transition (SRT)22, with a continuous rotation of the spin direction with respect to the crystallographic axes (Fig. 4a) and a progressive alignment of the total ferromagnetic moment with the a axis. Thus, for T < TSRT, the c-axis-oriented effective magnetic field associated with the atomic loops is no longer parallel to the ferromagnetic moment (S1 + S2), but becomes parallel to the antiferromagnetic moment (S1 − S2). As a consequence23,24, a different quasi-ferromagnetic (q-FM) mode is excited17 (Fig. 4b), with a frequency that depends strongly on the temperature (Fig. 4c)22.

The effects above are further clarified when compared to calculations of the lattice and spin dynamics in ErFeO3. We concentrate on the measurements taken at 100 K (T > TSRT) and on the excitation of the quasi-AFM mode reported in Figs 2 and 3. In the calculations reported in Fig. 5, we solved Maxwell’s equations in time and space (see Supplementary Section 7), simulating the lattice polarization along each axis as a mixture of driven Lorentz oscillators (Fig. 5a, b). The degree of rotation of the total polarization could then be estimated as (Pua+ub × ∂ Pua+ub/∂t) (see Supplementary Section 8). As shown in the calculations of Fig. 5c (light purple), a pulse of elliptical motion develops at the surface of the material immediately after the phonons have been excited with a linear polarization. This dynamical lattice rotation ‘propagates’ into the material at a speed of 0.4 × 108 m s−1 (13% c). This combination of two phonon-polaritons carries with it an effective magnetic field (Fig. 5d, see Supplementary Section 8) that results in the excitation of spin waves. Note that after a picosecond the rotation inverts its sign, although damping reduces the amplitude of the loops, causing a total breaking of time-reversal invariance.

a,b, Time-dependent polarization at the surface of the material. A 10 MV cm−1 amplitude, 130 fs duration pulse tuned around 19.5 THz initiates the phonon-polariton response of the material along axes a and b, respectively. c, Circularity of the surface polarization. Owing to the non-degenerate nature of the excited polar modes, the ions on each axis react to the same driver with different initial phases and evolve at different rates. Hence, the total lattice polarization inside the material is elliptical. Furthermore, the initial phase of the infrared-active phonons (light and dark purple) determines the initial direction of rotation of the ions and, consequently, the sign of the effective magnetic field. d, Elliptically polarized phonon-polariton propagation. The pair of phonon-polaritons propagates inside the material at a speed of 0.4 × 108 m s−1 and carries an effective magnetic field. e, Solution of the Landau–Lifshitz equation for the q-AFM magnon. We solved the Landau–Lifshitz equation in time for every layer of material (space resolution), considering as a driver the time-dependent phonon-generated atomic-loop amplitude of d. We then integrated only the signal seen by the propagating probe (oblique dotted blue line) for different pump–probe delays and normalized to the static magnetization value (inset e). A fitting parameter was used to match the simulated magnon amplitude with the measured one to estimate the value of the effective magnetic field generated by the phonons.

The magnon amplitude can be estimated at all points in time and space (Fig. 5e) by solving the Landau–Lifshitz equation25, driven by the calculated time- and space-dependent effective field of Fig. 5d. The phase-matched signal measured by the probe (dotted lines in Fig. 5e) is shown in the inset of Fig. 5e. By comparing the size of the calculated signal with the measured signal, we can recover the total amplitude of the magnetic precession and the effective magnetic field strength, which is estimated to be 36 mT for a fluence of 20 mJ cm−2.

Note that the effect reported here could be made larger by increases in the field strength, but also optimized by an appropriate choice of phonon resonances and by shaping the optical field to enhance phase matching. As the effect operates at mid-infrared and terahertz frequencies, it may become applicable in new devices that operate in this wavelength regime.

Finally, beyond the applications to magnetism discussed here, we note that control of ionic loops can be viewed as a perturbation of the Berry connection26,27, and in appropriate circumstances may be used to manipulate the topological properties of materials28,29 through phonons.

Methods

Experimental set-up.

The mid-infrared pulses used in the experiment were generated by difference frequency generation (DFG) in a GaSe crystal between the signal outputs of two optical parametric amplifiers (OPAs), pumped with 5-mJ, 800-nm wavelength pulses, 100 fs in duration, at a 1 KHz repetition rate delivered from a commercial regenerative amplifier. The two OPAs were seeded by the same white light continuum (WLC), producing phase-locked31 signal pulses (300 μJ, about 70 fs in duration, independently tunable from 1.2 μm to 1.5 μm). As a consequence, the generated mid-infrared transients were carrier-envelope-phase (CEP) stable (>6 μJ across the 18 to 36 THz range, about 100 fs in duration)32. The pump pulses were characterized by electro-optic sampling (Supplementary Section 2) and by a Michelson Fourier transform interferometer.

A small fraction of the regenerative amplifier output (100 fs in duration) was used to probe the Faraday rotation using a balanced detection configuration. A half-wave plate and polarizer were put in front of the sample to align the polarization of the incoming light along one of its crystallographic axes (a or b). The angle between pump (normal incidence) and probe was 18°. After the sample, a second half-wave plate and a Wollaston prism were used to balance the intensity on two identical diodes, whose differential signal was measured by a lock-in amplifier as a function of the pump–probe delay (an optical chopper was put on the mid-infrared beam).

A schematic representation of the set-up is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Sample.

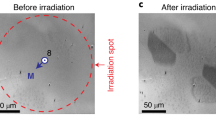

The sample used in the experiment is a bulk single crystal, 95 μm thick, c-cut, grown using the floating zone method.

During the measurements the sample was kept in an external magnetic field, directed along the c axis, and strong enough to saturate the small ferromagnetic moment.

The orthoferrite temperature was controlled with a cold finger cryostat.

The in-plane axes were determined by static birefringence measurements (Supplementary Section 3). The polarization resolved reflectivity was obtained by means of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Supplementary Section 4).

Simulations.

The dynamical properties of ErFeO3 were obtained by solving Maxwell’s equations in space (one-dimensional) and time for each axis (Supplementary Section 7). The lattice response was modelled by expressing the permittivity ɛr as a series of damped harmonic oscillators corresponding to the infrared-active phonons, plus a term ɛ∞ taking into account the permittivity due to high-energy excitations (Lorentz model):

The values of the plasma frequency ωp, the TO frequency ω0 and the damping Γ for each of the k phonons were extracted from a Lorentz fit to the static reflectivity measurements.

The atomic displacement and the resulting effective magnetic field were estimated from the calculated lattice polarization (Supplementary Section 8).

The magnetic dynamics was obtained by solving the Landau–Lifshitz equation following the approach developed in ref. 25. The calculated effective magnetic field was used as the source term.

Data availability.

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Först, M. et al. Nonlinear phononics as an ultrafast route to lattice control. Nat. Phys. 7, 854–856 (2011).

Subedi, A., Cavalleri, A. & Georges, A. Theory of nonlinear phononics for coherent light control of solids. Phys. Rev. B 89, 220301(R) (2014).

Rini, M. et al. Control of the electronic phase of a manganite by mode-selective vibrational excitation. Nature 449, 72–74 (2007).

Caviglia, A. D. et al. Ultrafast strain engineering in complex oxide heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 136801 (2012).

Först, M. et al. Driving magnetic order in a manganite by ultrafast lattice excitation. Phys. Rev. B 84, 241104(R) (2011).

Först, M. et al. Spatially resolved ultrafast magnetic dynamics launched at a complex-oxide hetero-interface. Nat. Mater. 14, 883–888 (2015).

Kaiser, S. et al. Optically induced coherent transport far above Tc in underdoped YBa2Cu3O6+δ . Phys. Rev. B 89, 184516 (2014).

Hu, W. et al. Optically enhanced coherent transport in YBa2Cu3O6.5 by ultrafast redistribution of interlayer coupling. Nat. Mater. 13, 705–711 (2014).

Mitrano, M. et al. Possible light-induced superconductivity in K3C60 at high temperature. Nature 530, 461–464 (2016).

Tsymbal, L. T. et al. Natural behavior of the magnetization under spontaneous reorientation: TmFeO3, ErFeO3 . Low Temp. Phys. 31, 277–282 (2005).

Gupta, H. C. et al. Lattice dynamic investigation of Raman and infrared wavenumbers at the zone center of orthorhombic RFeO3 (R = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm) perovskites. J. Raman Spectrosc. 33, 67–70 (2002).

Korenev, V. L. et al. Long-range p–d exchange interaction in a ferromagnet–semiconductor hybrid structure. Nat. Phys. 12, 85–91 (2016).

Kubacka, T. et al. Large-amplitude spin dynamics driven by a THz pulse in resonance with an electromagnon. Science 343, 1333–1336 (2014).

Katsura, H., Nagaosa, N. & Balatsky, A. V. Spin current and magnetoelectric effect in noncollinear magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 057205 (2005).

Spaldin, N. A. & Fiebig, M. The renaissance of magnetoelectric multiferroics. Science 309, 391–392 (2005).

Koshizuka, N. & Ushioda, S. Inelastic-light-scattering study of magnon softening in ErFeO3 . Phys. Rev. B 22, 5394–5399 (1980).

White, R. M., Nemanich, R. J. & Herring, C. Light scattering from magnetic excitations in orthoferrites. Phys. Rev. B 25, 1822–1836 (1982).

Pisarev, R. V. et al. Charge transfer transitions in multiferroic BiFeO3 and related ferrite insulators. Phys. Rev. B 79, 235128 (2009).

Fleury, P. A. & Loudon, R. Scattering of light by one- and two-magnon excitations. Phys. Rev. 166, 514 (1968).

Pershan, P. S., van der Ziel, J. P. & Malmstrom, L. D. Theoretical discussion of the inverse Faraday effect, Raman scattering, and related phenomena. Phys. Rev. 143, 574–583 (1966).

Kirilyuk, A., Kimel, A. V. & Rasing, T. Ultrafast optical manipulation of magnetic order. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2731–2784 (2010).

Yamaguchi, K. et al. Terahertz time-domain observation of spin reorientation in orthoferrite ErFeO3 through magnetic free induction decay. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 137204 (2013).

Iida, R. et al. Spectral dependence of photoinduced spin precession in DyFeO3 . Phys. Rev. B 84, 064402 (2011).

Kimel, A. V. et al. Ultrafast non-thermal control of magnetization by instantaneous photomagnetic pulses. Nature 435, 655–657 (2005).

Mikhaylovskiy, R. V. et al. Ultrafast optical modification of exchange interactions in iron oxides. Nat. Commun. 6, 8190 (2015).

Abedi, A., Maitra, N. T. & Gross, E. K. U. Correlated electron-nuclear dynamics: exact factorization of the molecular wavefunction. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 22A530 (2012).

Min, S. K., Abedi, A., Kim, K. S. & Gross, E. K. U. Is the molecular Berry phase an artifact of the Born–Oppenheimer approximation? Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 263004 (2014).

Sentef, M. A. et al. Theory of Floquet band formation and local pseudospin textures in pump–probe photoemission of graphene. Nat. Commun. 6, 7047 (2015).

Wang, Y. H. et al. Observation of Floquet–Bloch states on the surface of a topological insulator. Science 342, 453–457 (2013).

Deng, G. et al. The magnetic structures and transitions of a potential multiferroic orthoferrite ErFeO3 . J. Appl. Phys. 117, 164105 (2015).

Cerullo, G., Baltuška, A., Mücke, O. D. & Vozzi, C. Few-optical-cycle light pulses with passive carrier-envelope phase stabilization. Laser Photon. Rev. 5, 323–351 (2011).

Sell, A., Scheu, R., Leitenstorfer, A. & Huber, R. Field-resolved detection of phase-locked infrared transients from a compact Er:fiber system tunable between 55 and 107 THz. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 251107 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to A. Subedi, D. M. Juraschek, M. Fechner and N. A. Spaldin for sharing the calculated phonon eigenvectors and for useful discussions. We thank R. V. Pisarev for providing the samples. We additionally acknowledge support from J. Harms (for graphics), D. Nicoletti (for FTIR measurements) and G. Meier (for sample characterization). A.V.K., R.V.M. and D.B. thank I. Razdolski for fruitful discussions of the first experiments and Th. Rasing for continuous support. The research leading to these results received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement no. 319286 (QMAC). We acknowledge support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft via the excellence cluster ‘The Hamburg Centre for Ultrafast Imaging—Structure, Dynamics and Control of Matter at the Atomic Scale’. A.V.K., R.V.M. and D.B. acknowledge partial support by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) Grant No. 281043 (Femtospin).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Cavalleri conceived the project together with T.F.N. T.F.N. and A.Cartella built the mid-infrared pump/Faraday-rotation probe experimental set-up with help from A.Cantaluppi and M.F. T.F.N. and A.Cartella performed the measurements. A.Cartella and T.F.N. developed the 1D-FDTD code and performed the simulations with help from R.V.M. (for the solution of the Landau–Lifshitz equation). T.F.N. analysed the experimental data. A.V.K., R.V.M. and D.B. identified the material system for the project and helped in the analysis of the data. R.M. collaborated in the interpretation of the data. The manuscript was written by T.F.N. and A.Cavalleri, with feedback from all co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (PDF 892 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nova, T., Cartella, A., Cantaluppi, A. et al. An effective magnetic field from optically driven phonons. Nature Phys 13, 132–136 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3925

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3925

This article is cited by

-

Three-stage ultrafast demagnetization dynamics in a monolayer ferromagnet

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Phononic switching of magnetization by the ultrafast Barnett effect

Nature (2024)

-

Terahertz electric-field-driven dynamical multiferroicity in SrTiO3

Nature (2024)

-

Terahertz-field-driven magnon upconversion in an antiferromagnet

Nature Physics (2024)

-

Light makes atoms behave like electromagnetic coils

Nature (2024)