Abstract

Graphene nanoribbons display extraordinary optical properties due to one-dimensional quantum-confinement, such as width-dependent bandgap and strong electron–hole interactions, responsible for the formation of excitons with extremely high binding energies. Here we use femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy to explore the ultrafast optical properties of ultranarrow, structurally well-defined graphene nanoribbons as a function of the excitation fluence, and the impact of enhanced Coulomb interaction on their excited states dynamics. We show that in the high-excitation regime biexcitons are formed by nonlinear exciton–exciton annihilation, and that they radiatively recombine via stimulated emission. We obtain a biexciton binding energy of ≈250 meV, in very good agreement with theoretical results from quantum Monte Carlo simulations. These observations pave the way for the application of graphene nanoribbons in photonics and optoelectronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Slicing graphene into nanoribbons (GNRs) allows to open a bandgap in the graphene electronic structure, owing to the quasi-one-dimensional confinement1. This has important implications for electronic devices, such as GNR transistors2, and forms the basis of the emerging field of graphene nanoplasmonics3,4. Especially appealing is also the possibility to additionally tailor specific properties through edge-structure engineering, such as magnetic ordering in zigzag terminated GNRs5,6. Further improvements along these lines are envisaged on the basis of recent advances in fabrication7,8,9,10 and processing routes11,12. In particular, the bottom-up synthesis7,8 of GNRs based on molecular precursors designed on purpose has proven capable of reaching nanometric widths with atomically precise edges, a regime where the GNR properties are widely tunable1. While single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) cannot be prepared with single chirality and require further processing with surfactants for the sorting13,14, the bottom-up synthesis directly affords GNRs with a uniform chemical structure with 100% selectivity. Thus, prepared GNRs show well-defined electronic and optical properties, which are fully determined by their specific structure and can be further tuned by modulation of their width and edge configuration10,15,16 as well as by atomically controlled doping12,17. All of this holds promise for application in next-generation optoelectronic and photonic devices, as recently suggested by the realization of all-GNR-based heterojunctions12,18 and by other proposals for photovoltaic applications16,19,20.

In spite of this interest, the field of GNRs is still in its infancy and little is known about their photophysical properties, especially in the non-equilibrium regime. Extraordinary optical properties were predicted21,22,23, such as width-dependent bandgap and the formation of excitons with extremely high binding energies, which have been only recently demonstrated in bottom-up GNRs15,24,25,26. In particular, the pronounced excitonic effects26 are accompanied by a significant increase of the optical absorbance, as compared with graphene, for light that is linearly polarized along the ribbon axis. At this stage, the understanding of the excited-state relaxation dynamics of GNRs would offer not only a deeper insight into the fundamental physics of these ideal one-dimensional systems but also a benchmark for their integration in advanced optoelectronic devices27.

In the following, we apply resonant ultrafast pump–probe spectroscopy to nanometre-wide atomically precise GNRs obtained by a bottom-up solution synthesis8 to study the kinetics of excitons and their interactions in the saturation (that is, nonlinear) excitation regime. For high-excitation fluences, we observe bimolecular exciton annihilation and the concomitant ultrafast (≈1 ps) buildup of a stimulated emission (SE) signal from an excited biexciton state that is populated via a nonlinear process, a result that is extremely promising in view of applications of GNRs as tuneable active materials in lasers and light-emitting diodes.

Results

Linear absorption of GNRs

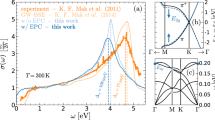

The GNRs studied here, characterized by cove-shaped edge morphology and hereafter labelled 4CNR (following the notation in ref. 16), were chemically synthesized as described in ref. 8. Their aromatic core structure, displayed in Fig. 1a (inset), features a modulated width of 0.7–1.1 nm, and is functionalized with long and branched alkyl chains (2-decyltetradecyl) at the outer benzene rings to guarantee dispersibility in organic solvents. The linear absorption spectrum of the GNR sample in tetrahydrofuran (THF) dispersion is shown in Fig. 1a (black curve), and compared with the simulated gas-phase spectrum obtained from ab initio GW plus Bethe–Salpeter (GW-BS) calculations (blue arrows), performed on H-passivated 4CNR (details concerning the calculations are reported in the Methods section). THF was chosen as a solvent to minimize aggregation of GNRs, which would significantly alter their optical properties. The effect of the solvent on the spectrum is instead expected to be minor (see, for example, ref. 28). The experimental spectrum is dominated by an optical transition of excitonic origin located at ≈570 nm, in good agreement with simulations. According to our GW-BS results, the first two excitons both arise from the linear combination of transitions among the two highest valence and two lowest conduction bands around the Γ point (mainly E12 and E21 transitions for the first and second exciton, respectively, as indicated in the band structure of Fig. 1b). In vacuum, excitons are tightly bound, with a giant binding energy of ∼1.5 eV (defined as the difference between the quasi-particle gap and the energy of the excitonic states), which is expected to diminish in presence of a dielectric environment.

(a) Linear absorption spectrum of the 4CNR sample in THF solution (black curve). A ball-and-stick model of the GNR without alkyl chains at the edges is shown in the inset. The experimental spectrum is compared with the result of GW-BS calculations, with excitonic transitions indicated by blue arrows. (b) GW quasi-particle band structure. The lines indicate the transitions that are mainly contributing to the first and second exciton. The 1.5 eV difference between the GW gap (b; grey area) and the excitonic transition reported in a defines the exciton binding energy in vacuum.

Ultrafast pump–probe spectroscopy of GNRs

We performed broadband pump–probe spectroscopy of the 4CNR samples using resonant excitation at 570 nm and white-light probing covering the 500–700 nm range, with an overall temporal resolution of ≈100 fs (see Methods for details of the experimental setup). Figure 2 shows the differential transmission (ΔT/T) spectra for different pump–probe delays (Fig. 2a), and the ΔT/T dynamics at 600 nm probe wavelength (Fig. 2b), when the sample is excited with a low fluence of ≈100 μJ cm−2. In the ΔT/T spectra we clearly distinguish two bands: (i) an intense photo-bleaching (PB) of the excitonic transition peaked at ≈570 nm, which we assign to ground-state depletion and/or phase space filling of the excited state; (ii) a relatively weak red-shifted photo-induced absorption (PA) band starting from ≈620 nm. Since these two bands have the same decay kinetics (Fig. 2b), we attribute the PA signal to excited-state absorption from the exciton to higher energy states or to the e–h continuum. The comparison of the ΔT/T spectra (Fig. 2a) for different pump–probe delays (from 500 fs to 50 ps) also highlights that the signal decays without any significant spectral evolution at this excitation fluence, thus indicating a simple relaxation mechanism of the excited state (either radiative via emission of photons and/or non-radiative via interaction with phonons).

To understand the carrier relaxation process, we can take as a reference the large amount of experimental results on SWNTs, since we expect them to display similar recombination dynamics. SWNTs also show complex, multi-component decay kinetics. In the low-excitation fluence regime, the long-lived (>5 ps) decay components in SWNTs have been reproduced with a bi-exponential model, which includes both the radiative and non-radiative lifetime29,30,31,32. Other studies describe these decay dynamics by a model for a diffusion-limited regime33,34 or geminate e–h recombination in one dimension35, thus leading to a power law (≈t−0.5) kinetics. Since a detailed study of the dynamics of these long-lived photoexcitations for GNRs is beyond the scope of this paper, we fit the kinetics of the PB signal at 600 nm probe wavelength with a simple bi-exponential decay model (Fig. 2b), which gives us the timescale of the relaxation processes. From the fit we obtain τ1≈6 ps and τ2≈330 ps, in good agreement with the results obtained for SWNTs30.

Instead, we concentrate on the ultrafast (<5 ps) decay dynamics, and in particular on their dependence on the excitation fluence, as we show in Fig. 3. The normalized ΔT/T spectra at different excitation fluences for a 1 ps pump–probe delay (Fig. 3a) display very similar, fluence-independent PB and PA spectral features, while for a 5 ps pump–probe delay (Fig. 3b) we unambiguously observe the buildup, with increasing fluence, of a positive and red-shifted ΔT/T peak, at ≈650 nm. From a general point of view, a positive ΔT/T signal in pump–probe experiments describes either a PB or a SE process. We here assign the peak at ≈650 nm to a SE process, since (i) it does not correspond to any resonant feature in the linear absorption spectrum (Fig. 1a), as also confirmed by simulations, being instead red-shifted with respect to the main excitonic transition (at ≈570 nm); and (ii) it appears with a ≈ps delay with respect to the pump pulse and only at high-excitation fluences. We note that photons produced by SE are identical (phase, energy and momentum) to the probe photons and thus can be detected in pump–probe experiments, at variance with those produced by spontaneous emission.

Normalized ΔT/T spectra of 4CNRs for different excitation fluences at a fixed pump–probe delay of (a) 1 ps and (b) 5 ps. The inset in a reports the peak amplitude of the signal at 600 nm probe wavelength as a function of the excitation fluence (bottom x axis) and the exciton linear density (top x axis). Excitation-fluence-dependent dynamics at (c) 600 nm probe wavelength and (d) 650 nm probe wavelength. The fit (diamonds) is obtained from the coupled rate-equations (described in the text) based on exciton–exciton annihilation in one dimension. Inset in c represents the dynamics on a 100 ps timescale for 100 μJ cm−2 (low) and 1 mJ cm−2 (high) fluences, together with the bi-exponential fit used in Fig. 2b.

Exciton–exciton annihilation and biexciton formation in GNRs

To clarify the origin of this SE signal, we concentrate on the fluence-dependent dynamics at the probe wavelengths of 600 nm, that is, the PB signal, and 650 nm, that is, the SE signal (Fig. 3c and d, respectively). We immediately observe that, for increasing fluence, the PB signal (Fig. 3c) displays a faster decay, while, correspondingly, the signal at 650 nm (Fig. 3d) undergoes a clear change in sign (from negative to positive) that corresponds to the delayed formation of the SE signal. First, let us analyse the fast PB decay at 600-nm probe wavelength (Fig. 3c). In semiconducting SWNTs the appearance of an ultrafast fluence-dependent decay component is explained by exciton–exciton annihilation, a two-exciton interaction process, in which one exciton recombines to the ground state and the other either dissociates into a free e–h pair or is promoted into a higher energy level36,37,38. Such process is also commonly observed in other one-dimensional semiconductors, such as conjugated polymers39,40, and it has been recently observed also in monolayer MoS2 (ref. 41). Theoretical calculations42 also predict that an Auger-like mechanism occurs in semiconducting armchair GNRs because of effectively enhanced Coulomb interaction. In their work, Konabe et al.42 find an exciton–exciton annihilation time in the order of few ps for 1.2–2.5 nm wide GNRs. After the initial ultrafast nonlinear decay process, the dynamics at all pump fluences are instead the same. This can be noticed by comparing the kinetics of the PB signal at high and low fluences over the full temporal range (inset in Fig. 3c). Being a two-body interaction process, exciton–exciton annihilation is expected to display a nonlinear dependence on the exciton density (see Methods for details) and/or the excitation fluence37, in agreement with our experimental results (inset in Fig. 3a).

Second, we need to understand the origin of the delayed formation of the SE signal at 650 nm (Fig. 3d). As we have already discussed, following exciton–exciton annihilation both free e–h pairs and/or higher energy-excited states can be formed. The first scenario has been observed in SWNTs, where the creation of charges in the high-excitation regime leads to the formation of trions43,44, which are detected as a negative (PA) and red-shifted ΔT/T signal. Clearly, this scenario is in contrast with our experimental results, which present a positive (SE) signal. Instead, the formation of a delayed and red-shifted SE signal in the high-excitation regime was observed in semiconducting quantum-dots (QDs)45,46,47,48, another prototype of quantum-confined systems. In the case of QDs, the SE signal was explained in terms of emission from biexcitons and the energy distance between the main exciton PB signal and the biexciton SE signal gives the biexciton binding energy, which is typically of the order of few tens of meV. For our GNRs, the SE peak corresponds to a much larger value for the biexciton binding energy, that is, Eb≈250 meV. This value is in accordance with the comparably larger exciton binding energies in GNRs, that are at least one order of magnitude larger than in QDs due to the reduced screening as well as the extreme two-dimensional and transversal confinements. The following photoexcitation scenario in GNRs thus emerges: at high-excitation fluences, exciton–exciton annihilation leads to the population of a radiative biexciton state, which then undergoes SE to the one-exciton level upon interaction with the probe pulse (Fig. 4a).

(a) Sketch of the energetic levels and the kinetic model described in the text. (b) Biexciton (XX) binding energy (Eb,XX) as a function of the lateral dimension (L), that is, width for GNRs (black squares) and diameter for SWNTs (grey circles). The data, obtained by guide-function QMC simulations, are shown in dimensionless exciton units, as detailed in the text. In these units, the binding energy of the 4CNR is ∼3.4 Ry*. The dashed line indicates the two-dimensional value of Eb,XX=0.77 Ry*.

Discussion

To support our assignment, we first compute the biexciton binding energy in GNRs by means of guide-function quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) simulations, using an envelope function approach with effective masses, as previously reported in ref. 49 for SWNTs. Full description of the method is reported in the Methods section. In Fig. 4b, we show the biexciton binding energy dependence on the lateral confinement in dimensionless exciton units, that is, distances are measured in units of the effective Bohr radius  and energies in units of the effective Rydberg

and energies in units of the effective Rydberg  , where μ is the reduced e–h mass, ɛ is the dielectric constant, aB is the Bohr radius and e is the electron charge. By considering an average reduced mass as obtained from ab initio calculations (computed as the weighted average relative to the E21 and E12 transitions, that is, μ=0.22), the average width of the 4CNR (w=0.84 nm), and the dielectric constant of the solvent (ɛ=7.5), we obtain a biexciton binding energy of 180 meV, in good agreement with the experimental result of 250 meV. The discrepancy with respect to experiments is reasonable in view of the simplified description scheme used here, which is not expected to capture all microscopic details.

, where μ is the reduced e–h mass, ɛ is the dielectric constant, aB is the Bohr radius and e is the electron charge. By considering an average reduced mass as obtained from ab initio calculations (computed as the weighted average relative to the E21 and E12 transitions, that is, μ=0.22), the average width of the 4CNR (w=0.84 nm), and the dielectric constant of the solvent (ɛ=7.5), we obtain a biexciton binding energy of 180 meV, in good agreement with the experimental result of 250 meV. The discrepancy with respect to experiments is reasonable in view of the simplified description scheme used here, which is not expected to capture all microscopic details.

In Fig. 4b, we also report the biexciton binding energy for SWNTs, calculated by the same approach49: for a SWNT of similar lateral dimension, we find a binding energy that is less than one-half of that of the 4CNR in dimensionless units. This can be understood by considering the different biexciton confinement, since in the case of SWNTs the biexciton wavefunction is delocalized over the whole circumference, whereas in GNRs it becomes strongly confined in the transversal direction. The value obtained for GNRs is quite large also in comparison with the biexciton binding energy Eb≈50 meV of different monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides obtained by recent transient absorption50 and photoluminescence experiments51.

To further confirm our interpretation, we finally reproduce the temporal evolution of the exciton (that is, decay of the PB signal) and the biexciton (that is, formation of the SE signal) populations with the following coupled rate-equations52,53,54:

where nE and nB are the exciton and biexciton population, respectively, k10 is the decay rate from the exciton to the ground state, k21 is the radiative decay rate from the biexciton to the exciton producing the SE signal and ke–e is the exciton annihilation rate constant (see Fig. 4a for the adopted model). The t−0.5 dependence of the exciton annihilation rate arises from the one-dimensional diffusion mechanism of excitons, and its divergence for t→0 is cured by truncating it for times shorter than the width of the instrumental response function (IRF) (≈100 fs in our case). The quality of the fit (Fig. 3c,d) further confirms the validity of our model. From the fit we find that k10≈0 ps and k21≈0.15 ps−1, meaning that both mechanisms occur on a timescale that is longer with respect to the temporal window (5 ps) that we use for this analysis.

It is worth noting that we can fit our experimental data considering that all the excitons that undergo exciton–exciton annihilation form biexcitons. In particular, we can exclude that the observed SE signal is because of the dissociation of excitons into free e–h carriers, since SE from electrons in the continuum is not expected. Another possibility is that free e–h pairs get trapped into low-energy states; for example, due to defects. Nevertheless, since the selection rules for emission and absorption of photons are the same, the presence of such bright low-energy states should be detectable also in the linear absorption spectrum, and thus this scenario can be also excluded by looking at the absorption spectrum and theoretical simulations in Fig. 1. Thus, although we cannot exclude that free e–h carriers are formed, we can strongly assert that the observed SE arises from biexcitons. Since our model is able to correctly reproduce also the amplitude of the pump–probe signal without additional loss channels, we conclude that biexciton formation upon exciton–exciton annihilation is extremely efficient. Finally, for a fixed pump–probe delay we can also evaluate the annihilation rate  , which corresponds to an initial ka≈2 ps−1 for a pump–probe delay of 180 fs, close to our temporal resolution, and thus to an annihilation lifetime of ≈0.5 ps, in excellent agreement with experimental results on SWNTs54 and theoretical calculations on GNRs42.

, which corresponds to an initial ka≈2 ps−1 for a pump–probe delay of 180 fs, close to our temporal resolution, and thus to an annihilation lifetime of ≈0.5 ps, in excellent agreement with experimental results on SWNTs54 and theoretical calculations on GNRs42.

In conclusion, we studied the transient photophysical properties of ultranarrow structurally well-defined GNRs by means of ultrafast pump–probe spectroscopy. We show that a nonlinear decay channel for the main excitonic transition sets in at high excitation densities, and, correspondingly, we unambiguously observe a red-shifted SE signal. Our experiments demonstrate that exciton–exciton annihilation populates a radiative biexciton state, with an extremely high binding energy ≈250 meV, in agreement with estimates from QMC simulations. The high efficiency we find for both exciton–exciton annihilation and biexciton formation is of great importance, not only for gaining fundamental understanding on strongly enhanced quantum effects in low-dimensional materials but also for its implications in GNR-based optoelectronic devices. Indeed, the clear observation of a strong SE is extremely promising in view of using GNRs as active light-amplifying materials in tuneable lasers and light-emitting diodes. Moreover, our results suggest that also multiple-exciton generation55,56,57 can be extremely efficient in GNRs since it is governed by the same exciton–exciton annihilation rate. A detailed understanding of the photophysics of biexcitons and the mechanism of multiple-exciton generation will help to improve the efficiency of photovoltaic devices, with GNRs acting as light absorbers.

Methods

Pump–probe experimental setup

The experimental setup used for pump–probe measurements has been described in detail elsewhere58. In brief, the setup is based on a regeneratively amplified Ti:sapphire laser (Coherent, Libra) producing 100 fs, 4 mJ pulses at 800 nm wavelength and 1 kHz repetition rate. The probe pulse is obtained by focusing a fraction of the laser beam in a 2-mm-thick sapphire plate to generate a broadband single-filament white-light continuum. The pump pulse, generated by an optical parametric amplifier, is centred at 570 nm (at resonance with the main excitonic transition) with a bandwidth of ≈10 nm, corresponding to ≈70 fs duration. The probe light transmitted by the sample is dispersed on an optical multichannel analyser equipped with fast electronics, allowing single-shot recording of the probe spectrum at the full 1 kHz repetition rate. By changing the pump–probe delay, we record two-dimensional maps of the differential transmission (ΔT/T) signal as a function of probe wavelength and delay. The temporal resolution (taken as full-width at half-maximum of pump–probe cross-correlation) is ≈100 fs over the entire probe spectrum.

Exciton linear density estimation

To estimate the exciton linear density reported in the inset of Fig. 3a, we proceed as follows: (i) we calculate the number of absorbed photons cm−2 from the measured pump fluence, the measured absorbance, and the pump photon energy (2.18 eV); (ii) we calculate the number of excitons cm−2 by considering an exciton photogeneration efficiency (Quantum Yield) of 96% based on optical pump—THz probe experiments on similar GNRs59; and (iii) we multiply this value by the concentration (0.0021, g l−1) of the dispersion and divide by the mass of a unit length of the GNRs (0.83 × 10−21 g nm−1). This estimate gives a density of ∼0.2–0.3 excitons nm−1 for pump fluences below 100 μJ cm−2, corresponding to an average distance between excitons of ∼4–5 nm. Such a value appears to be sufficient to prevent exciton–exciton interactions.

Coherent artefacts in pump–probe dynamics

The coupled-rate equations used to model the evolution of the exciton and biexciton populations are solved by taking into account both the IRF and possible coherent artefacts present in pump–probe measurements. For our experimental setup the IRF is the cross-correlation of the pump and probe pulses, and can be quite accurately modelled by a Gaussian function with ≈100 fs full-width at half-maximum. Possible coherent artefacts in pump–probe experiments are stimulated Raman amplification and cross-phase modulation (XPM)60. We fitted the initial 100 fs of the PB signal at 600 nm (Fig. 3c) including the IRF to reproduce the initial buildup and a Gaussian function (the same used for the IRF) to reproduce the initial ultrafast stimulated Raman amplification coherent artefact. For the SE dynamics at 650 nm (Fig. 3d), instead, we include also XPM, which we fit as the first derivative of a Gaussian function (the same used for the cross-correlation). Although extremely simple, this model correctly reproduces not only the evolution but also the initial steps of the pump–probe signal.

Thermal effects and sample heating

Time-resolved experiments were carried out at room temperature, assuming negligible temperature effects on the spectra on the basis of previous results on SWNTs (see, for example, ref. 61). Regarding the sample heating during experiments, we also expect negligible temperature changes upon photoexcitation. In fact, we can estimate a maximum increase in temperature of ∼0.1 K, based on a comparison with the work of Abdelsayed et al.62, and by considering the following parameters: volume of the sample (0.3 ml), THF heat capacity (123 J mol−1 K−1), density (889 kg m−3), molar mass (72 g mol−1) and laser total energy (∼100 nJ per pulse at 500 Hz for 10 min of irradiation, corresponding to 30 mJ). This indicates that we are working in a perturbative regime for what concerns thermal effects.

GW-BS calculations for the static absorption

The ground-state atomic structure of the 4CNR was optimized by using the PWscf code of the Quantum ESPRESSO package (ref. 63), which is based on a plane-wave pseudopotential implementation of density functional theory. Calculations were performed by employing local density approximation exchange correlation (xc) functional and norm-conserving pseudopotentials, with a cutoff energy for the wavefunctions of 60 Ry. The atomic positions within the cell were fully relaxed until forces were <5 × 10−4 Ry bohr−1, while the lattice constant along the periodic direction was optimized separately. The Brillouin zone was sampled with 16 k-points along the periodic direction. The Kohn-Sham band structure obtained for the optimized geometry was improved by introducing many-body corrections within the G0W0 approximation for the self-energy operator. Here, the dynamic dielectric function was obtained within the plasmon-pole approximation, by employing a box-shaped truncation of the Coulomb potential64 to remove the long-range interaction between periodic images. The optical absorption spectrum was then computed as the imaginary part of the macroscopic dielectric function starting from the solution of the BS equation, which allows for the inclusion of e–h interaction effects. The static screening in the direct term was calculated within the random-phase approximation with inclusion of local field effects; the Tamm–Dancoff approximation for the BS Hamiltonian was employed. The aforementioned GW-BS calculations, performed by using the YAMBO code (ref. 65), were carried out for the fully H-passivated 4CNR, that is, by removing the alkyl side chains, in order to make them computationally affordable. We have checked that the different passivation does not affect the band structure properties at the density functional theory and local density approximation level in the energy window of interest for the determination of the optical absorption. Similar results were reported in ref. 66.

The guide function quantum Monte Carlo approach

Atomistic simulations as the ones described above are presently unfeasible for the investigation of biexcitons in realistic systems. Here we resort to an effective model based on guide function QMC simulations, as previously reported in ref. 49 for SWNTs. For the (unnormalized) guide function we use

where r1,2 (ra,b) are the dimensionless positions of the two electrons (holes), and  is the distance between particles confined to the two-dimensional nanoribbon. The Monte Carlo simulation approach is the same as in ref. 49 with the only exception that we add a box-like confinement potential

is the distance between particles confined to the two-dimensional nanoribbon. The Monte Carlo simulation approach is the same as in ref. 49 with the only exception that we add a box-like confinement potential

along the transversal direction, with V0=1,000, β=20 and w the GNR width. In the simulations we use 20,000 walkers67, a time step of Δt=0.25 × 10−4, an equilibration interval of 20,000 and a measurement interval of 30,000 time steps. The smoothed confinement potential and the time step were chosen such that for ‘typical’ paths the inequality  holds68. We checked that the biexciton binding energy did not change substantially upon modifying Δt or other simulation parameters. The QMC approach has been able to predict quite accurately the biexciton binding energy of SWNTs. In fact, Colombier et al.69 detected the presence of biexcitons in SWNTs embedded in a gelatine matrix by means of nonlinear optical spectroscopy, reporting a binding of 106 meV energy for the (9, 7) tube. The QMC model predicts a value of the binding energy of ≈100 meV assuming a dielectric constant of ɛ=3 (instead of 2.3 as appropriate for a gelatin matrix). Such an overestimation in the case of small values of ɛ is known for phenomenological models, whereas for larger values of ɛ (like the one considered in this work, i.e., ɛ=7.5) the QMC model is expected to give results similar to more refined (though not yet atomistic) approaches, as discussed in ref. 70.

holds68. We checked that the biexciton binding energy did not change substantially upon modifying Δt or other simulation parameters. The QMC approach has been able to predict quite accurately the biexciton binding energy of SWNTs. In fact, Colombier et al.69 detected the presence of biexcitons in SWNTs embedded in a gelatine matrix by means of nonlinear optical spectroscopy, reporting a binding of 106 meV energy for the (9, 7) tube. The QMC model predicts a value of the binding energy of ≈100 meV assuming a dielectric constant of ɛ=3 (instead of 2.3 as appropriate for a gelatin matrix). Such an overestimation in the case of small values of ɛ is known for phenomenological models, whereas for larger values of ɛ (like the one considered in this work, i.e., ɛ=7.5) the QMC model is expected to give results similar to more refined (though not yet atomistic) approaches, as discussed in ref. 70.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Soavi, G. et al. Exciton-exciton annihilation and biexciton stimulated emission in graphene nanoribbons. Nat. Commun. 7:11010 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11010 (2016).

References

Castro Neto, A. H., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109–162 (2009).

Schwierz, F. Graphene transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 487–496 (2010).

Chen, J. et al. Optical nano-imaging of gate-tunable graphene plasmons. Nature 487, 77–81 (2012).

Rodrigo, D. et al. Mid-infrared plasmonic biosensing with graphene. Science 349, 165–168 (2015).

Son, Y.-W., Cohen, M. L. & Louie, S. G. Half-metallic graphene nanoribbons. Nature 444, 347–349 (2006).

Magda, G. Z. et al. Room-temperature magnetic order on zigzag edges of narrow graphene nanoribbons. Nature 514, 608–611 (2014).

Cai, J. et al. Atomically precise bottom-up fabrication of graphene nanoribbons. Nature 466, 470–473 (2010).

Narita, A. et al. Synthesis of structurally well-defined and liquid-phase-processable graphene nanoribbons. Nat. Chem. 6, 126–132 (2014).

Jacobberger, R. M. et al. Direct oriented growth of armchair graphene nanoribbons on germanium. Nat. Commun. 6, 8006 (2015).

Narita, A., Wang, X.-Y., Feng, X. & Müllen, K. New advances in nanographene chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 6616–6643 (2015).

Bennett, P. B. et al. Bottom-up graphene nanoribbon field-effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 253114 (2013).

Cai, J. et al. Graphene nanoribbon heterojunctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 896–900 (2014).

Yang, F. et al. Chirality-specific growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes on solid alloy catalysts. Nature 510, 522–524 (2014).

Omachi, H., Nakayama, T., Takahashi, E., Segawa, Y. & Itami, K. Initiation of carbon nanotube growth by well-defined carbon nanorings. Nat. Chem. 5, 572–576 (2013).

Narita, A. et al. Bottom-up synthesis of liquid-phase-processable graphene nanoribbons with near-infrared absorption. ACS Nano 8, 11622–11630 (2014).

Osella, S. et al. Graphene nanoribbons as low band gap donor materials for organic photovoltaics: quantum chemical aided design. ACS Nano 6, 5539–5548 (2012).

Kawai, S. et al. Atomically controlled substitutional boron-doping of graphene nanoribbons. Nat. Commun. 6, 8098 (2015).

Chen, Y.-C. et al. Molecular bandgap engineering of bottom-up synthesized graphene nanoribbon heterojunctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 156–160 (2015).

Yan, X., Cui, X., Li, B. & Li, L. Large, solution-processable graphene quantum dots as light absorbers for photovoltaics. Nano Lett. 10, 1869–1873 (2010).

Lee, S. L. et al. An organic photovoltaic featuring graphene nanoribbons. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 51, 9185–9188 (2015).

Prezzi, D., Varsano, D., Ruini, A., Marini, A. & Molinari, E. Optical properties of graphene nanoribbons: the role of many-body effects. Phys. Rev. B 77, 041404 (2008).

Yang, L., Cohen, M. L. & Louie, S. G. Excitonic effects in the optical spectra of graphene nanoribbons. Nano Lett. 7, 3112–3115 (2007).

Prezzi, D., Varsano, D., Ruini, A. & Molinari, E. Quantum dot states and optical excitations of edge-modulated graphene nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. B 84, 041401 (2011).

Ruffieux, P. et al. Electronic structure of atomically precise graphene nanoribbons. ACS Nano 6, 6930–6935 (2012).

Linden, S. et al. Electronic structure of spatially aligned graphene nanoribbons on Au(788). Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 216801 (2012).

Denk, R. et al. Exciton-dominated optical response of ultra-narrow graphene nanoribbons. Nat. Commun. 5, 4253 (2014).

Bonaccorso, F., Sun, Z., Hasan, T. & Ferrari, A. C. Graphene photonics and optoelectronics. Nat. Photon. 4, 611–622 (2010).

Ohno, Y. et al. Excitonic transition energies in single-walled carbon nanotubes: dependence on environmental dielectric constant. Phys. Status Solidi B Basic Solid State Phys. 244, 4002–4005 (2007).

Styers-Barnett, D. J., Ellison, S. P., Park, C., Wise, K. E. & Papanikolas, J. M. Ultrafast dynamics of single-walled carbon nanotubes dispersed in polymer films. J. Phys. Chem. A 109, 289–292 (2005).

Chou, S. et al. Phonon-assisted exciton relaxation dynamics for a (6,5)-enriched DNA-wrapped single-walled carbon nanotube sample. Phys. Rev. B 72, 195415 (2005).

Dyatlova, O. A. et al. Ultrafast relaxation dynamics via acoustic phonons in carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 12, 2249–2253 (2012).

Huang, L., Pedrosa, H. N. & Krauss, T. D. Ultrafast ground-state recovery of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 017403 (2004).

Russo, R. M. et al. One-dimensional diffusion-limited relaxation of photoexcitations in suspensions of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 74, 041405 (2006).

Allam, J. et al. Measurement of a reaction-diffusion crossover in exciton-exciton recombination inside carbon nanotubes using femtosecond optical absorption. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 197401 (2013).

Soavi, G. et al. High energetic excitons in carbon nanotubes directly probe charge-carriers. Sci. Rep. 5, 9681 (2015).

Ma, Y.-Z., Valkunas, L., Dexheimer, S. L., Bachilo, S. M. & Fleming, G. R. Femtosecond spectroscopy of optical excitations in single-walled carbon nanotubes: evidence for exciton-exciton annihilation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 157402 (2005).

Valkunas, L., Ma, Y.-Z. & Fleming, G. R. Exciton-exciton annihilation in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 73, 115432 (2006).

Huang, L. & Krauss, T. D. Quantized bimolecular auger recombination of excitons in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 057407 (2006).

Maniloff, E. S., Klimov, V. I. & McBranch, D. W. Intensity-dependent relaxation dynamics and the nature of the excited-state species in solid-state conducting polymers. Phys. Rev. B 56, 1876 (1997).

Stevens, M. A., Silva, C., Russel, D. M. & Friend, R. H. Exciton dissociation mechanisms in the polymeric semiconductors poly(9,9-dioctylfluorene) and poly(9,9-dioctylfluorene-co-benzothiadiazole). Phys. Rev. B 63, 165213 (2001).

Sun, D. et al. Observation of rapid exciton–exciton annihilation in monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Nano Lett. 14, 5625–5629 (2014).

Konabe, S., Onoda, N. & Watanabe, K. Auger ionization in armchair-edge graphene nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. B 82, 073402 (2010).

Santos, S. M. et al. All-optical trion generation in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 187401 (2011).

Matsunaga, R., Matsuda, K. & Kanemitsu, Y. Observation of charged excitons in hole-doped carbon nanotubes using photoluminescence and absorption spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 037404 (2011).

Levy, R., Hönerlage, B. & Grun, J. B. Time-resolved exciton-biexciton transitions in CuCl. Phys. Rev. B 19, 2326 (1979).

Klimov, V. I. et al. Optical gain and stimulated emission in nanocrystal quantum dots. Science 290, 314–317 (2000).

Kreller, F., Lowisch, M., Puls, J. & Hennenberger, F. Role of biexcitons in the stimulated emission of wide-gap II-VI quantum wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 2420 (1995).

Klimov, I. V. Spectral and dynamical properties of multiexcitons in semiconductor nanocrystals. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 58, 635–673 (2007).

Kammerlander, D., Prezzi, D., Goldoni, G., Molinari, E. & Hohenester, U. Biexciton stability in carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 126806 (2006).

Sie, E. J., Lee, Y.-H., Frenzel, A. J., Kong, J. & Gedik, N. Intervalley biexcitons and many-body effects in monolayer MoS2 . Phys. Rev. B 92, 125417 (2015).

You, Y. et al. Observation of biexcitons in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Phys. 11, 477–481 (2015).

Lüer, L. et al. Size and mobility of excitons in (6, 5) carbon nanotubes. Nat. Phys. 5, 54–58 (2009).

Martini, I. B., Smith, A. D. & Schwartz, B. J. Exciton-exciton annihilation and the production of interchain species in conjugated polymer films: comparing the ultrafast stimulated emission and photoluminescence dynamics of MEH-PPV. Phys. Rev. B 69, 035204 (2004).

Wang, F., Duckovic, G., Knoesel, E., Brus, L. E. & Heinz, T. F. Observation of rapid Auger recombination in optically excited semiconducting carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 70, 241403 (R) (2004).

Schaller, R. D. & Klimov, V. I. High efficiency carrier multiplication in PbSe nanocrystals: implications for solar energy conversion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 186601 (2004).

Wang, S., Khafizov, M., Tu, X., Zheng, M. & Krauss, T. D. Multiple exciton generation in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 10, 2381–2386 (2010).

Konabe, S. & Okada, S. Multiple exciton generation by a single photon in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 227401 (2012).

Polli, D., Lüer, L. & Cerullo, G. High-time-resolution pump-probe system with broadband detection for the study of time-domain vibrational dynamics. Rev. Sci. Intrum. 78, 103108 (2007).

Jensen, S. A. et al. Ultrafast photoconductivity of graphene nanoribbons and carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 13, 5925–5930 (2013).

Lorenc, M. et al. Artifacts in femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. B 74, 19–27 (2002).

Fantini, C. et al. Optical transition energies for carbon nanotubes from resonant raman spectroscopy: environment and temperature effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 147406 (2004).

Abdelsayed, V. et al. Photothermal deoxygenation of graphite oxide with laser excitation in solution and graphene-aided increase in water temperature. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 2804–2009 (2010).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Rozzi, C. A., Varsano, D., Marini, A., Gross, E. K. U. & Rubio, A. Exact Coulomb cutoff technique for supercell calculations. Phys. Rev. B 73, 205119 (2006).

Marini, A., Hogan, C., Grüning, M. & Varsano, D. Yambo: an ab initio tool for excited state calculations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 1392–1403 (2009).

Villegas, C. E. P., Mendoca, P. B. & Rocha, A. R. Optical spectrum of bottom-up graphene nanoribbons: towards efficient atom-thick excitonic solar cells. Sci. Rep 4, 6579 (2014).

Thijssen, J. M. Computational Physics Cambridge University Press (2007).

Hüser, M. H. & Berne, B. J. Circumventing the pathological behavior of path-integral Monte Carlo for systems with Coulomb potentials. J. Chem Phys. 107, 571–575 (1997).

Colombier, L. et al. Detection of a biexciton in semiconducting carbon nanotubes using nonlinear optical spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 197402 (2012).

Watanabe, K. & Asano, K. Biexcitons in semiconducting single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 83, 115406 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by MIUR PRIN Grant No. 20105ZZTSE, MIUR FIRB Grant No. RBFR12SWOJ, and MAE Grant No. US14GR12. It has been supported in part by the Austrian Science Fund FWF, under the SFB F49 NextLite, by NAWI Graz, the European Research Council grant on NANOGRAPH, DFG Priority Program SPP 1459 and European Union Projects MoQuaS. G.C., A.N., X.F. and K.M. acknowledge support by the EC under Graphene Flagship (contract no. CNECT-ICT-604391). Computing time was provided by the Center for Functional Nanomaterials at Brookhaven National Laboratory, supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract number DE-SC0012704.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N., Y. H., X.F. and K.M. prepared the GNR sample. G.S., S.D.C., D.V., C.M. and G.C. performed the pump–probe experiments. G.S. and D.V. performed the data analysis and simulation with the coupled-rate equations model. D.P., U.H. and E.M. performed the simulations on the exciton and biexciton binding energies. G.S., D.P. and G.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors designed the research and discussed the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Soavi, G., Dal Conte, S., Manzoni, C. et al. Exciton–exciton annihilation and biexciton stimulated emission in graphene nanoribbons. Nat Commun 7, 11010 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11010

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11010

This article is cited by

-

Versatile optical manipulation of trions, dark excitons and biexcitons through contrasting exciton-photon coupling

Light: Science & Applications (2023)

-

Photophysics of nanographenes: from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to graphene nanoribbons

Photosynthesis Research (2022)

-

Lightwave-driven scanning tunnelling spectroscopy of atomically precise graphene nanoribbons

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the graphene era

Science China Chemistry (2019)

-

Diels–Alder polymerization: a versatile synthetic method toward functional polyphenylenes, ladder polymers and graphene nanoribbons

Polymer Journal (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.