Abstract

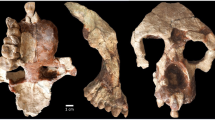

There are thousands of fossils of hominins, but no fossil chimpanzee has yet been reported. The chimpanzee (Pan) is the closest living relative to humans1. Chimpanzee populations today are confined to wooded West and central Africa, whereas most hominin fossil sites occur in the semi-arid East African Rift Valley. This situation has fuelled speculation regarding causes for the divergence of the human and chimpanzee lineages five to eight million years ago. Some investigators have invoked a shift from wooded to savannah vegetation in East Africa, driven by climate change, to explain the apparent separation between chimpanzee and human ancestral populations and the origin of the unique hominin locomotor adaptation, bipedalism2,3,4,5. The Rift Valley itself functions as an obstacle to chimpanzee occupation in some scenarios6. Here we report the first fossil chimpanzee. These fossils, from the Kapthurin Formation, Kenya, show that representatives of Pan were present in the East African Rift Valley during the Middle Pleistocene, where they were contemporary with an extinct species of Homo. Habitats suitable for both hominins and chimpanzees were clearly present there during this period, and the Rift Valley did not present an impenetrable barrier to chimpanzee occupation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ruvolo, M. E. Molecular phylogeny of the hominoids: inferences from multiple independent DNA sequence data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14, 248–265 (1997)

Darwin, C. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (John Murray, London, 1871)

Washburn, S. L. in Changing Perspectives on Man (ed. Rothblatt, B.) 193–201 (Univ. Chicago Press, Chicago, 1968)

Kortlandt, A. New Perspectives on Ape and Human Evolution (Univ. Amsterdam, Amsterdam, 1972)

Pilbeam, D. & Young, N. Hominoid evolution: synthesizing disparate data. C. R. Palevol. 3, 305–321 (2004)

Coppens, Y. East side story: the origin of mankind. Sci. Am. 270, 88–95 (1994)

Martyn, J. The Geologic History of the Country Between Lake Baringo and the Kerio River, Baringo District, Kenya (PhD dissertation, Univ. London, 1969)

Tallon, P. in Geological Background to Fossil Man (ed. Bishop, W. W.) 361–373 (Scottish Academic Press, Edinburgh, 1978)

McBrearty, S., Bishop, L. C. & Kingston, J. Variability in traces of Middle Pleistocene hominid behaviour in the Kapthurin Formation, Baringo, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 30, 563–580 (1996)

McBrearty, S. in Late Cenozoic Environments and Hominid Evolution: a Tribute to Bill Bishop (eds Andrews, P. & Banham, P.) 143–156 (Geological Society, London, 1999)

McBrearty, S. & Brooks, A. The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behaviour. J. Hum. Evol. 39, 453–563 (2000)

Deino, A. & McBrearty, S. 40Ar/39Ar chronology for the Kapthurin Formation, Baringo, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 42, 185–210 (2002)

Leakey, M., Tobias, P. V., Martyn, J. E. & Leakey, R. E. F. An Acheulian industry with prepared core technique and the discovery of a contemporary hominid at Lake Baringo, Kenya. Proc. Prehist. Soc. 35, 48–76 (1969)

Wood, B. A. & Van Noten, F. L. Preliminary observations on the BK 8518 mandible from Baringo, Kenya. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 69, 117–127 (1986)

Renaut, R. W., Tiercelin, J.-J. & Owen, B. in Lake Basins Through Space and Time (eds Gierlowski-Kordesch, E. H. & Kelts, K. R.) 561–568 (Am. Assoc. Petrol. Geol., Tulsa, Oklahoma, 2000)

Bishop, L. C., Hill, A. P. & Kingston, J. in Late Cenozoic Environments and Hominid Evolution: a Tribute to Bill Bishop (eds Andrews, P. & Banham, P.) 99–112 (Geological Society, London, 1999)

Johanson, D. C. Some metric aspects of the permanent and deciduous dentition of the pygmy chimpanzee (Pan paniscus). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 41, 39–48 (1974)

Dean, M. C. & Reid, D. J. Perikymata spacing and distribution on hominid anterior teeth. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 116, 209–215 (2001)

Swindler, D. R. Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-Human Primates (CUP, Cambridge, 2002)

Kinzey, W. G. in The Pygmy Chimpanzee (ed. Susman, R. L.) 65–88 (Plenum, New York, 1984)

Smith, B. H., Crummett, T. L. & Brandt, K. L. Ages of eruption of primate teeth: a compendium for aging individuals and comparing life histories. Yearb. Phys. Anthropol. 37, 177–232 (1994)

Kuykendall, K. L., Mahoney, C. J. & Conroy, G. C. Probit and survival analysis of tooth emergence ages in a mixed-longitudinal sample of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 89, 379–399 (1992)

Anemone, R. L., Watts, E. S. & Swindler, D. R. Dental development of known-age chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes (Primates, Pongidae). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 86, 229–241 (1991)

Skinner, M. F. & Hopwood, D. Hypothesis for the causes and periodicity of repetitive linear enamel hypoplasia in large, wild African (Pan troglodytes and Gorilla gorilla) and Asian (Pongo pygmaeus) apes. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 123, 216–235 (2004)

Uchida, A. Craniodental Variation Among the Great Apes (Harvard Univ. Peabody Mus., Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1996)

Johanson, D. C. An Odontological Study of the Chimpanzee with Some Implications for Hominoid Evolution (PhD dissertation, Univ. Chicago, 1974)

Kormos, R., Boesch, C., Bakarr, M. I. & Butynski, T. M. West African Chimpanzees: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (IUCN Publication Unit, Cambridge, 2003)

McGrew, W. C., Baldwin, P. J. & Tutin, C. E. G. Chimpanzees in a hot, dry and open habitat: Mt. Assirik, Senegal. J. Hum. Evol. 10, 227–244 (1981)

McGrew, W. C., Marchant, L. F. & Nishida, T. Great Ape Societies (CUP, Cambridge, 1996)

Kingston, J. D., Marino, B. & Hill, A. P. Isotopic evidence for Neogene hominid palaeoenvironments in the Kenya Rift Valley. Science 264, 955–959 (1994)

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank B. Kimeu, N. Kanyenze and M. Macharwas, who found the chimpanzee fossils reported here. Research in the Kapthurin Formation is carried out with the support of an NSF grant to S.M., and under a research permit from the Government of the Republic of Kenya and a permit to excavate from the Minister for Home Affairs and National Heritage of the Republic of Kenya. Both of these are issued to A. Hill and the Baringo Paleontological Research Project, an expedition conducted jointly with the National Museums of Kenya. We also thank personnel of the Departments of Palaeontology, Ornithology and Mammalogy of the National Museums of Kenya, Nairobi; A. Zihlman; and Y. Hailie-Selassie, L. Jellema and M. Ryan for curation and access to specimens. We express gratitude to A. Hill for his comments on the manuscript. We also thank G. Chaplin for drafting Fig. 1, B. Warren for preparing Figs 3 and 4, and A. Bothell for help with submission of the figures. We are grateful to J. Kelley, J. Kingston, M. Leakey, R. Leakey, C. Tryon, A. Walker and S. Ward for discussions. We thank G. Suwa for his remarks.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Reprints and permissions information is available at npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McBrearty, S., Jablonski, N. First fossil chimpanzee. Nature 437, 105–108 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04008

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04008

This article is cited by

-

Postcranial evidence of late Miocene hominin bipedalism in Chad

Nature (2022)

-

Similar patterns of genetic diversity and linkage disequilibrium in Western chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) and humans indicate highly conserved mechanisms of MHC molecular evolution

BMC Evolutionary Biology (2020)

-

Parturitions, menopause and other physiological stressors are recorded in dental cementum microstructure

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Ancient admixture from an extinct ape lineage into bonobos

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2019)

-

Food mechanical properties and isotopic signatures in forest versus savannah dwelling eastern chimpanzees

Communications Biology (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.