Abstract

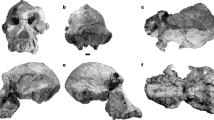

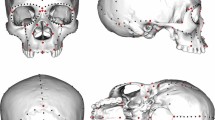

Homo neanderthalensis has a unique combination of craniofacial features that are distinct from fossil and extant ‘anatomically modern’ Homo sapiens (modern humans). Morphological evidence, direct isotopic dates1 and fossil mitochondrial DNA from three Neanderthals2,3 indicate that the Neanderthals were a separate evolutionary lineage for at least 500,000 yr. However, it is unknown when and how Neanderthal craniofacial autapomorphies (unique, derived characters) emerged during ontogeny. Here we use computerized fossil reconstruction4 and geometric morphometrics5,6 to show that characteristic differences in cranial and mandibular shape between Neanderthals and modern humans arose very early during development, possibly prenatally, and were maintained throughout postnatal ontogeny. Postnatal differences in cranial ontogeny between the two taxa are characterized primarily by heterochronic modifications of a common spatial pattern of development. Evidence for early ontogenetic divergence together with evolutionary stasis of taxon-specific patterns of ontogeny is consistent with separation of Neanderthals and modern humans at the species level.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Stringer, C. B. & Gamble, C. In Search of the Neanderthals: Solving the Puzzle of Human Origins (Thames and Hudson, London, 1993).

Krings, M. et al. A view of Neandertal genetic diversity. Nature Genet. 26, 144–146 (2000).

Ovchinnikov, I. V. et al. Molecular analysis of Neanderthal DNA from the northern Caucasus. Nature 404, 490–493 (2000).

Zollikofer, C. P. E., Ponce de León, M. S. & Martin, R. D. Computer-assisted paleoanthropology. Evol. Anthropol. 6, 41–54 (1998).

Bookstein, F. L. Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1991).

Rohlf, F. J. in Contributions to Morphometrics (eds Marcus, L., Bello, E. & García-Valdecasas, A.) 131–159 (Consejo superior de investigaciones científicas, Madrid, 1993).

Tillier, A.-M. in The Human Revolution. Behavioural and Biological Perspectives on the Origins of Modern Humans (eds Mellars, P. & Stringer, C. B.) 286–297 (Edinburgh Univ. Press, Edinburgh, 1989).

Rak, Y., Kimbel, W. H. & Hovers, E. A Neanderthal infant from Amud Cave, Israel. J. Hum. Evol. 26, 313–324 (1994).

Dean, M. C., Stringer, C. B. & Bromage, T. G. Age at death of the Neanderthal child from Devil's Tower, Gibraltar and the implications for studies of general growth and development in Neanderthals. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 70, 301–309 (1986).

Stringer, C. B., Dean, M. C. & Martin, R. D. in Primate Life History and Evolution (ed. DeRousseau, C. J.) 115–152 (Wiley-Liss, New York, 1990).

Williams, F. l. E. in Neanderthals on the Edge (eds Stringer, C. B., Barton, R. N. E. & Finlayson, J. C.) 257–267 (Oxbow Books, Oxford, 2000).

Zollikofer, C. P. E., Ponce de León, M. S., Martin, R. D. & Stucki, P. Neanderthal computer skulls. Nature 375, 283–285 (1995).

Ponce de León, M. S. & Zollikofer, C. P. E. New evidence from Le Moustier 1: computer-assisted reconstruction and morphometry of the skull. Anat. Rec. 254, 474–489 (1999).

Ponce de León, M. S. Neanderthal Ontogeny: a Geometric Morphometric Analysis of Cranial Growth. PhD thesis, Univ. Zürich (2000).

O'Higgins, P. & Jones, N. Facial growth in Cercocebus torquatus: an application of three-dimensional geometric morphometric techniques to the study of morphological variation. J. Anat. 193, 251–272 (1998).

Rak, Y. The Neanderthal: a new look at an old face. J. Hum. Evol. 15, 151–164 (1986).

Trinkaus, E. The Neandertal face: evolutionary and functional perspectives on a recent hominid face. J. Hum. Evol. 16, 429–443 (1987).

Schwartz, J. H. & Tattersall, I. Significance of some previously unrecognized apomorphies in the nasal region of Homo neanderthalensis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 10852–10856 (1996).

Rosas, A. Occurrence of Neanderthal features in mandibles from the Atapuerca-SH site. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 114, 74–91 (2001).

Enlow, D. H. Facial Growth 3rd edn (Saunders, Philadelphia, 1990).

Lieberman, D. E., Pearson, O. M. & Mowbray, K. M. Basicranial influence on overall cranial shape. J. Hum. Evol. 38, 291–315 (2000).

Franciscus, R. G. & Trinkaus, E. Determinants of retromolar space presence in Pleistocene Homo mandibles. J. Hum. Evol. 28, 577–595 (1995).

Lieberman, D. E. in Development, Growth and Evolution (eds O'Higgins, P. & Cohn, M. J.) 85–122 (Linn. Soc. Lond., London, 2000).

Maureille, B. & Bar, D. The premaxilla in Neandertal and early modern children: ontogeny and morphology. J. Hum. Evol. 37, 137–152 (1999).

Lieberman, D. E. Sphenoid shortening and the evolution of modern human cranial shape. Nature 393, 158–162 (1998).

Lieberman, D. E., Ross, C. F. & Ravosa, M. J. The primate cranial base: ontogeny, function, and integration. Yb. Phys. Anthropol. 43, 117–169 (2000).

Lieberman, D. E. & McCarthy, R. C. The ontogeny of cranial base angulation in humans and chimpanzees and its implications for reconstructing pharyngeal dimensions. J. Hum. Evol. 36, 487–517 (1999).

Tattersall, I. & Schwartz, J. H. Morphology, paleoanthropology and Neanderthals. New Anat. 253, 113–117 (1998).

Ubelaker, D. H. Human Skeletal Remains. Excavation, Analysis, Interpretation (Chicago Univ. Press, Chicago, 1978).

Zollikofer, C. P. E. & Ponce de León, M. S. Tools for rapid prototyping in the biosciences. IEEE Comp. Graph. Appl. 15, 48–55 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to R. D. Martin and P. Stucki for support of our research. C. B. Stringer's continuous help and advice is gratefully acknowledged. We thank C. Howell, J.-J. Jaeger, D. Lieberman, J. Schwartz and C. Pryce for valuable comments on an earlier version of this paper. We appreciate the help of the following curators in providing access to fossil specimens: J.-J. Cleyet-Merle, J.-M. Cordy, V. Kharitonov, M. Marinot, F. Menghin, R. Orban, I. Pap, Y. Rak, C. B. Stringer, B. Vandermeersch. We also thank the radiologists, physicists and technicians engaged in fossil computer tomography scanning: E. Berenyi, G. Bijl, P. Dondelinger, V. Dousset, W. Fuchs, S. Louryan, V. Makarenko, U. Shreter, N. Strickland and C. L. Zollikofer. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and a habilitation grant of the Canton of Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Tables 1 to 3

Table 1: Description of the Neanderthal and the "anatomically modern" Homo sapiens (AMH) sample. (XLS 21 kb)

Table 2: Definitions of the cranial and mandibular landmarks.

Table 3: Statistics of relative warp analyses of the cranio-mandibular, cranial and mandibular landmark configurations.

NeanderthalToSapiens.mov

The animation shows shape transformation of an average Neanderthal skull into an average AMH skull while size is held constant. (MOV 587 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ponce de León, M., Zollikofer, C. Neanderthal cranial ontogeny and its implications for late hominid diversity. Nature 412, 534–538 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/35087573

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/35087573

This article is cited by

-

Evolutionary development of the Homo antecessor scapulae (Gran Dolina site, Atapuerca) suggests a modern-like development for Lower Pleistocene Homo

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Less tautology, more biology? A comment on “high-density” morphometrics

Zoomorphology (2020)

-

Creating diversity in mammalian facial morphology: a review of potential developmental mechanisms

EvoDevo (2018)

-

The Suitability of 3D Data: 3D Digitisation of Human Remains

Archaeologies (2018)

-

Neanderthal-Derived Genetic Variation Shapes Modern Human Cranium and Brain

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.