Credit: Cultura Creative (RF)/ Alamy Stock Photo

China's diaspora key to science collaborations

23 June 2016

Cultura Creative (RF)/ Alamy Stock Photo

Links formed by mainland China's large scientific diaspora and its increasing output of high-quality research make it an emerging centre of international collaboration.

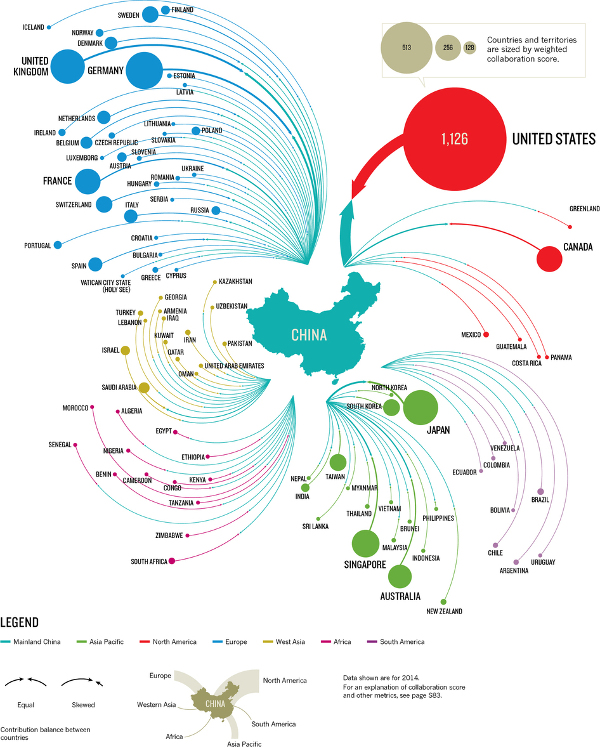

After more than a decade of strong investment in research and higher education, China is becoming an important partner for the scientific powerhouses of North America and Europe, and a growing hub for international collaboration. Mapping the many Chinese international collaborations in the Nature Index (see 'China's global network') demonstrates the extent to which Chinese scientists have become innovative contributors to, and leaders of, many international scientific communities.

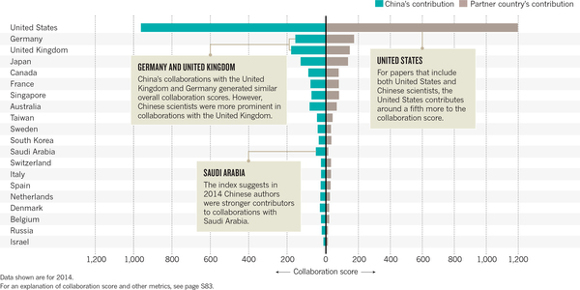

Like many nations, China's biggest collaborator in the Nature Index is the United States, the biggest index contributor overall, with a collaboration score more than five times that of its next strongest collaborating country, Germany. For China a contributing factor is the large number of Chinese researchers who have spent time in the global science superpower. A large diaspora of Chinese-heritage scientists around the world, particularly in the United States, have forged bonds between researchers in China and elsewhere. Indeed, more than 25% of scientists in the United States are from abroad and many of them are Chinese, notes Caroline Wagner, an associate professor who studies science and technology policy at the John Glenn College of Public Affairs, The Ohio State University in Columbus.

Small Multiples

In 2014, scientists from mainland China collaborated with counterparts in 94 other nations, making it one of the most connected countries in the Nature Index. Full size imageThe Chinese government has made huge efforts to incentivize a return to China by Chinese-born scientists. The Thousand Talent Program, operated by the Central Origination Department of the Communist Party is a prominent example of its efforts. “Many Chinese scholars have studied in the United States, and this contributes to international connections that continue after returning to China,” Wagner says.

Yet the growth in US–China collaboration has occurred in the absence of a supportive political mood in the United States. “We should be mindful of potential threats to the development of collaboration,” says Richard Suttmeier, professor of political science, emeritus, at the University of Oregon in Eugene.

“Concerns over national security and economic competitiveness, found in the United States, in China, and in other countries are probably not conducive to more robust patterns of collaboration,” Suttmeier adds.

However, collaborations between China and European countries have been partly driven by governmental efforts on all sides to exploit common interest and mutual benefits in strategic research areas, such as energy, public health and sustainable urbanization.

Recently, for example, the European Union and China launched a new co-funding mechanism to support joint research and innovation activities. Each year, more than €100 million from the EU's Horizon 2020 programme will be matched by at least 200 million yuan from Chinese programmes, for projects that involve European and Chinese participants. Before Horizon 2020, the EU ran the Framework Programme 7 from 2007 to 2013 in which China was the third largest international partner country, with 383 Chinese organizations participating in 274 collaborative research projects that garnered €35 million of funding from the EU.

Chinese policy is to encourage international cooperation in scientific research. Each of its government's three major agencies for science and technology — the Ministry of Science and Technology, the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Chinese Academy of Sciences — has its own international department to promote such collaborations.

Shared priorities

In the Nature Index, the number of collaborations between China and the UK has been rising quickly (see 'Pulling its weight'). At the University of Oxford, a combination of shared academic priorities, policy support and researcher exchanges are helping to drive this acceleration. “There are almost 200 Chinese academics in Oxford, and more than 4,000 Oxford alumni around China,” says Tao Dong, an immunologist at Oxford. Dong is also the Oxford-side founding director of a Centre for Translational Immunology (CTI) at Oxford, which is a joint venture between the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Oxford, as well as two other Chinese institutions. Dong believes that academic interest is the driving force for collaboration. “Research relevancy, mutual respect, and clear and up-front discussion on resources to facilitate research are essential.”

She adds that the support of key individuals in China, such as the Minister of Health, the mayor of Beijing, the president of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and the presidents and directors of universities and hospitals, has also been influential. “The CTI for example was endorsed as an area of collaborative research by the then Chinese Minister of Health during a visit of Oxford's VC to China.”

Alisdair Macdonald

China is a major contributor to its most significant international collaborations in the Nature Index in 2014. This graph shows the proportion of the total collaboration score that can be attributed to authors from mainland China. Full size imageResearch chemistry

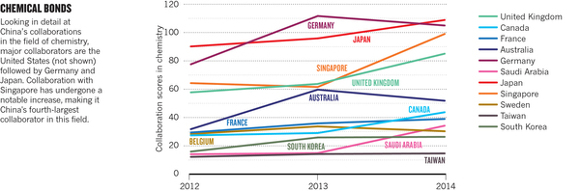

Much of the increase in China's output in the Nature Index since 2012 has been in chemistry. For example, there has been a dramatic rise in collaboration score between China and Singapore, with the partnership between the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) and the National University of Singapore (NUS) a notable example.

Two key players in this relationship are Benzhong Tang, in the Department of Chemistry at HKUST, who in 2001 discovered aggregation-induced emission, a novel photophysical phenomenon that enables light emission in the solid state, and Bin Liu, at the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at NUS, a bionanotechnology researcher investigating new materials. The collaboration has resulted in “more than 50 joint publications in high impact journals in the past four years”, says Liu. “The perfect matching of expertise and the nature of our complementary research has led to fruitful collaboration.”

“We work together not only to improve our own research, but also to help promote the whole community,” Liu adds. “There is now a quite large community of aggregation–induced–emission researchers.”

Alisdair Macdonald

Looking in detail at China's collaborations in the field of chemistry, major collaborators are the United States (not shown) followed by Germany, Japan and Singapore. Full size imagePhysical attraction

The United States aside, in the physical sciences China's international collaborations in the index are dominated by Germany. The relationship between the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) and the University of Stuttgart is particularly prominent.

These collaborations arise from practical, research-driven necessity, says Nan Zhao, a theoretical physicist at the Quantum Optics & Quantum Information group, Beijing Computational Science Research Center, who has coauthored papers with the scientists from USTC and Stuttgart.

“Some experiments simply cannot be done in China,” Zhao says. For instance, Germany's long history in the physical sciences means it has a capacity for sample preparation and manufacturing of experimental equipment that China lacks, says Zhao. German scientists, such as Zhao's collaborator Jörg Wrachtrup at Stuttgart, also provide valuable mentorship to their relatively inexperienced Chinese partners.

“Generally, we are 'students', and cannot start and lead an innovative research field yet”, says Zhao. Now based in Beijing, he has spent time at the University of Stuttgart, helping to build mutual understanding and trust with his collaborators.

“Innovative ideas are like sparks by chance, which cannot be planned or organized into projects. They can only be captured by deep and regular academic communication,” he says, “What the governments should not do is to set up barriers.”

By Peng Tian