A flight simulator developed by the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC), set up to challenge Boeing and Airbus in the passenger plane market. COMAC'S presence in Shanghai underlines the importance of access to finance and international talent for high-tech manufacturing. Credit: VCG VIA GETTY

Beijing and Shanghai are in a league of their own

China's political and economic centres connect on a scientific level.

1 November 2017

VCG VIA GETTY

A flight simulator developed by the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC), set up to challenge Boeing and Airbus in the passenger plane market. COMAC'S presence in Shanghai underlines the importance of access to finance and international talent for high-tech manufacturing.

Beijing and Shanghai, the most scientifically productive cities in China, also enjoy the highest city-to-city collaboration in the country. Last year, Beijing's contribution to journals included in the Nature Index, measured as weighted fractional count (WFC), was 1,693, and Shanghai's was 762. Together, they contributed to more papers than the next dozen cities combined. The two cities have also formed 382 bilateral institutional partnerships in 2016 — the highest city-pair in the country.

The strong scientific ties between Beijing and Shanghai have deep historical roots. Long before the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the two cities were centres of scholarship. In 1929, the National Academy of Peiping established nine departments, including physics, zoology and chemistry, in Beijing, and in the 1920s Academia Sinica set up medical and life sciences centres in Beijing and Shanghai. Many of these institutes were incorporated into the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in 1949 (although some of the Academia Sinica institutes moved to Taiwan that year).

Until the 1980s, when reforms began to open the economy to foreign investment, CAS and defence-related research organizations produced the majority of academic research in China, says policy analyst, Ning Li, at Eastern Washington University (EWU) in Cheney. “Very few Chinese universities did basic research,” he says. To this day, CAS remains the top contributor to the index, with 39 of its 110 institutes based in Beijing and 11 in Shanghai.

References:

- Municipal Bureau of Statistics for each city (2016)

- Guangdong Provincial Bureau of Statistics (2016)

- Tong, A. et al. Science and Technology Management Research 3, 1000–7695 (2017) (2014 data)

- United States Patent and Trademark Office (2016)

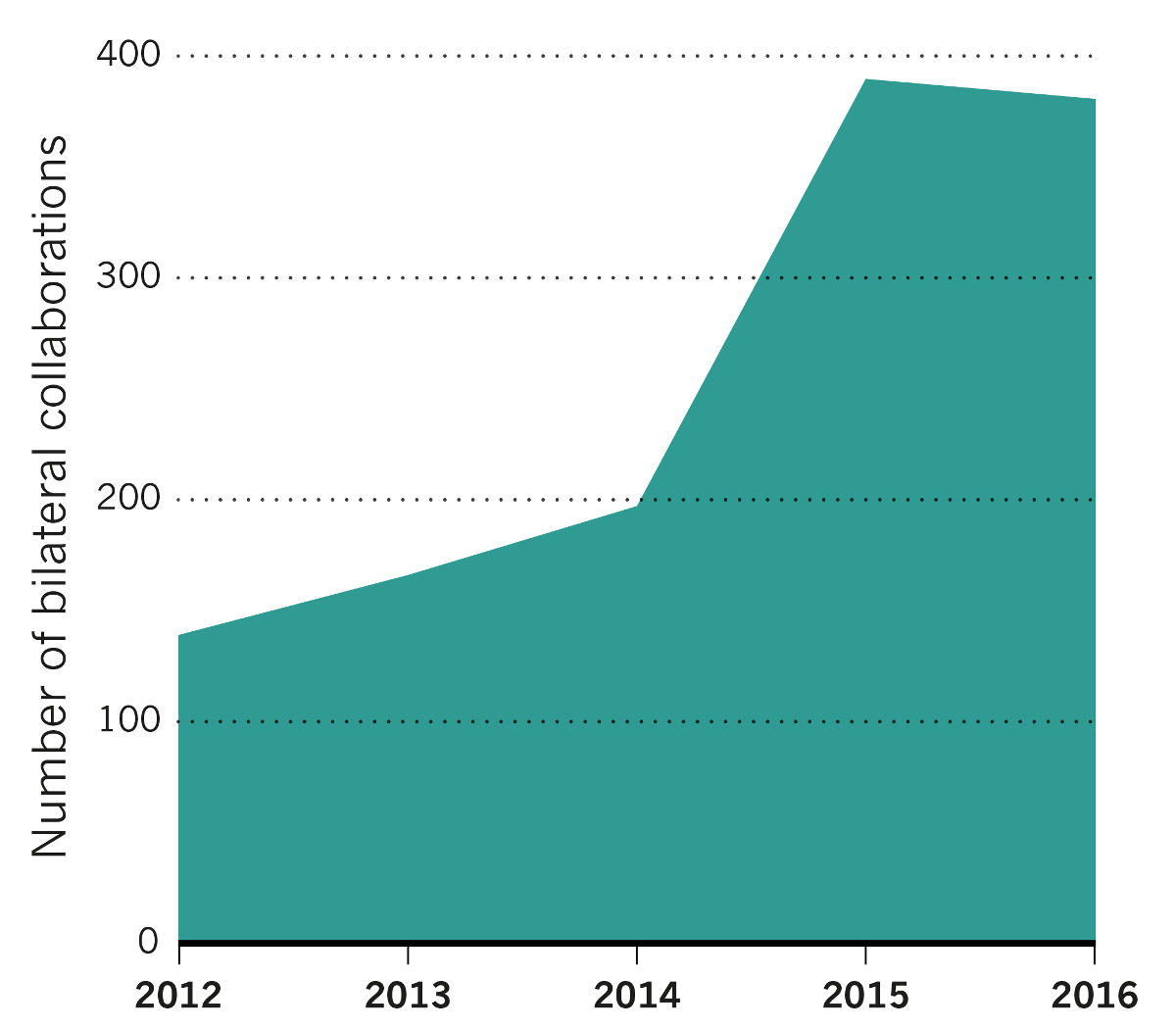

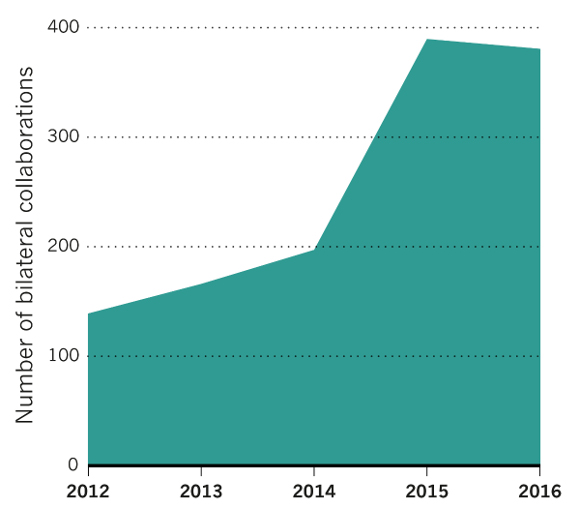

Bilateral Collaborations

The number of bilateral partnerships between an institution in Beijing and an institution in Shanghai has increased since 2012.

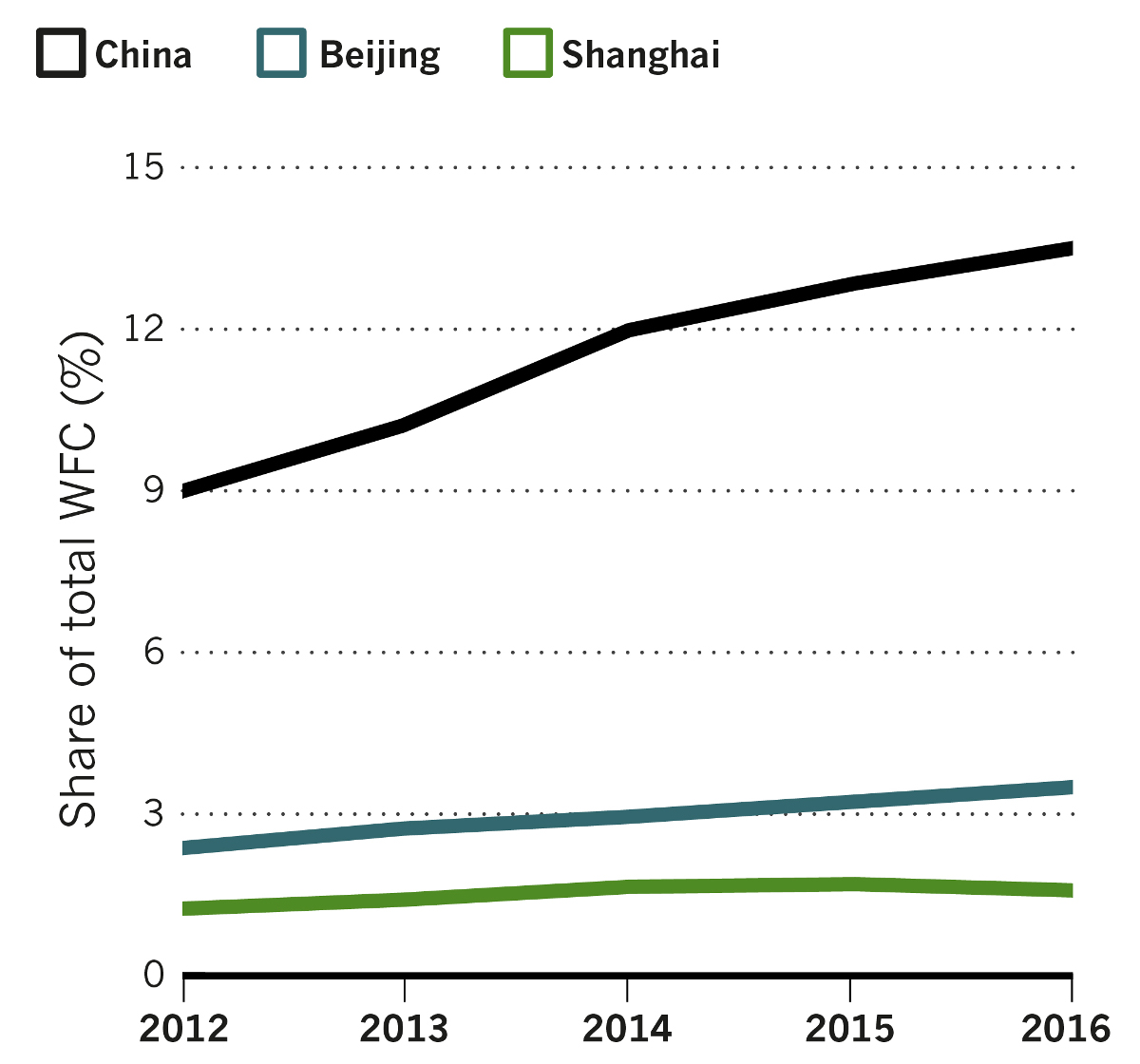

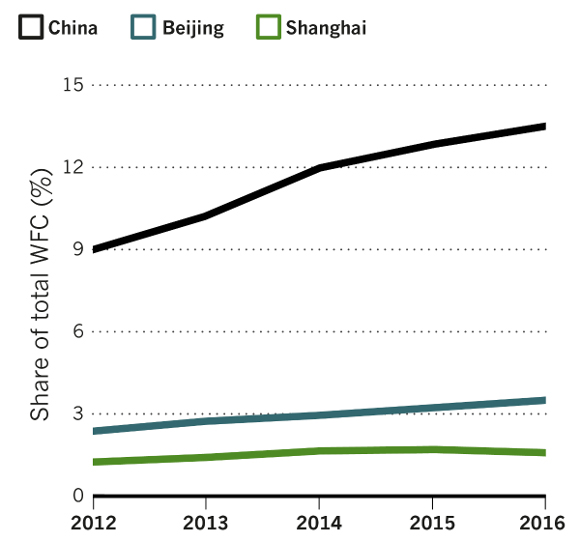

Share of output over time

City-level contribution to the share of authorship in the Nature Index, measured by the share of weighted fractional count (WFC) for that year, compared to China’s share.

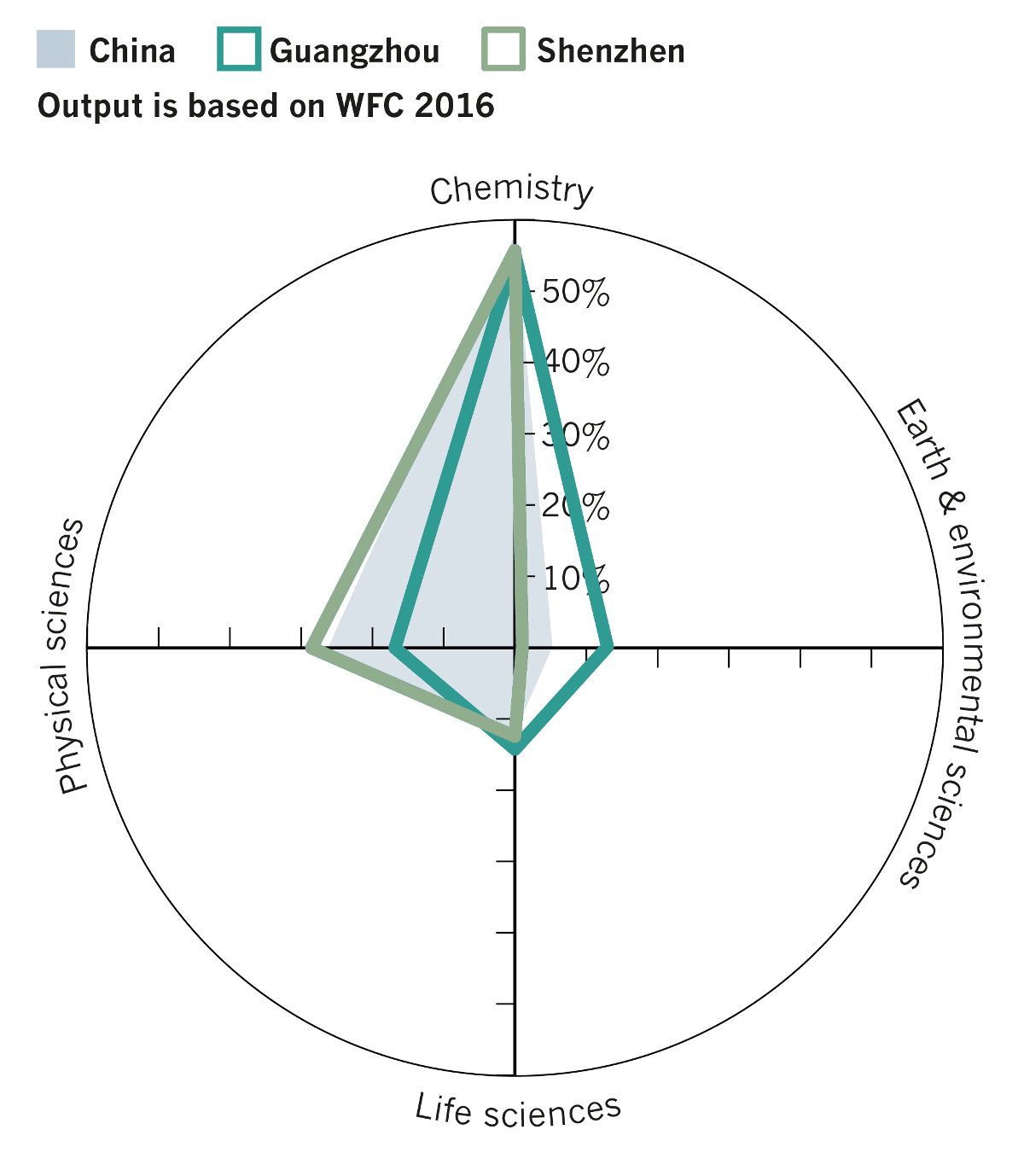

Subject strengths

Beijing and Shanghai contribute more to chemistry papers in the Nature Index than any other subject in the natural sciences.

Patterns of growth

China's economic rise dramatically boosted research activity across the country, and its two leading cities have been no exception. In 2016, Beijing's expenditure on research and development (R&D) was RMB148 billion (US$22 billion), accounting for 5.9% of its GDP, and Shanghai's was RMB103 billion (US$15.3 billion), accounting for 3.8% of its GDP. Between 2012 and 2016, researchers in Beijing increased their contribution to papers in the index by 43%, and Shanghai's contribution increased by 22%. These trends supported a national growth of 45% for the same period.

While sharing in the country's bounty, Beijing and Shanghai have followed different R&D paths. As the country's political centre, Beijing houses the national ministries, CAS headquarters, the China National Space Administration, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, as well as Peking University and Tsinghua University, among the top three universities in China in the Nature Index.

Beijing also retains the majority of headquarters for state-owned conglomerates, including the research wings of the China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation, the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, and the China Institute of Atomic Energy, all of which contributed to papers in the journals tracked by the index. Overall, more than 250 institutes in Beijing have contributed to the index in the past five years, compared to less than 150 in Shanghai.

But Shanghai, as China's finance and manufacturing metropolis, plays host to many more industrial research organizations than Beijing, says Du Debin, dean of the School of Urban and Regional Science at Shanghai-based East China Normal University. In 2008, for example, China set up the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC) in Shanghai to challenge the dominance of Boeing and Airbus in the passenger plane market. “COMAC's location in Shanghai confirms the importance of finance, markets and access to international talent in high-tech manufacturing,” Du says.

COMAC is not an isolated case. According to the Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau, by the end of 2016, the city was home to 411 foreign R&D centres — more than in any other city in China.

“Besides Shanghai's research infrastructure, the city is also more open to foreign investment,” says Li at EWU. It includes the country's first free-trade zone. What's more, he says the city's bureaucrats are more flexible in their enforcement of regulations to prioritize the needs of researchers and industry. While it could take months to ship living samples to Beijing due to stringent rules, for example, officials in Shanghai often approve shipments within a matter of days.

With many manufacturing bases located in the suburbs of Shanghai or the neighbouring provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, Shanghai is a more appealing destination for foreign R&D centres, says Li.

Adding to its appeal is a service industry that facilitates international commerce, for example with stores and restaurants open 24 hours.

Despite Shanghai's favourable environment for business, its residents tend to be risk-averse, says science policy analyst Cong Cao at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China. “Shanghai is quite conservative in terms of entrepreneurship,” he says. Beijing surpasses Shanghai as a destination for high-tech start-ups, particularly in the information technology sector. Its Zhongguancun area has become the capital of China's growing IT industry, chosen as the base for computer maker, Lenovo, and web services provider, Baidu, among other companies.

Friend and foe

Beijing and Shanghai both attract the best researchers from across the country and overseas. But Beijing's proximity to funding and decision-making bodies gives researchers in the capital a competitive edge when it comes to securing grants. “Our Beijing colleagues have an advantage because they are closer to science-related ministries, so they can lobby for funding and projects more easily,” says Ren Wei, a professor of physics at Shanghai University, who makes trips to Beijing to compete for major projects.

Incentives for cooperation remain strong. When seeking collaborations, scientists are often drawn to the top. “The best researchers in my fields are in Beijing and Shanghai, so it is natural that the two cities have the closest co-authorship in the Nature Index,” says Qiu Zilong, a neuroscientist at the CAS Institute of Neurology in Shanghai (which is part of the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences) (SIBS). In 2014, Qiu, working with colleagues at Beijing Normal University, identified a critical gene involved in neural plasticity during early postnatal development in mice, which was published in Nature Communications.

Many CAS institutes also promote cross-CAS collaborations that bring researchers from the two cities together. In the index, the most prolific institutional collaborations between the two cities involve the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and SIBS in Shanghai.

Zhang Shuangnan, a renowned astronomer at the Beijing-based CAS Institute of High Energy Physics, says many of his domestic collaborations are with Shanghai counterparts, such as the CAS Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, where some of his doctoral students are located. Zhang is currently working with colleagues at the CAS Shanghai Engineering Centre for Microsatellites, and French researchers, to develop a satellite for observing bright cosmic explosions known as gamma-ray bursts, which is scheduled to launch in 2021.