Abstract

We analyzed the mitochondrial DNA extracted from 14 human skeletal remains from the Doigahama site in Japan to clarify the genetic structure of the Doigahama Yayoi population and the relationship between burial style and kinship among individuals. The sequence types obtained in this study were compared with those of the modern Japanese, northern Kyushu Yayoi and ancient Chinese populations. We found that the northern Kyushu Yayoi populations belonged to the groups that include most of the modern Japanese population. In contrast, most of the Doigahama Yayoi population belonged to the group that includes a small number of the modern Japanese population. These results suggest that the Doigahama Yayoi population might have contributed less to the formation of the modern Japanese population than the northern Kyushu Yayoi populations. Moreover, when we examined the kinship between individuals in the Doigahama site, we found that the vicinal burial of adult skeletons indicated a maternal kinship, although that of juvenile skeletons did not. The vicinal burial style might have been influenced by many factors, such as paternal lineages, periods and geographical regions, as well as maternal lineages. In addition, skeletons considered to be those of shamans or leaders had the same sequence types. Their crucial social roles may have been inherited through maternal lineage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the generally accepted ‘dual structure model’ proposed by Hanihara1 with regard to population history in Japan, modern Japanese people have two morphologically and genetically distinguishable ancestral populations. One of them is the indigenous Jomon population as Neolithic hunter-gatherers. The other is the immigrant population that migrated from East Asia to the southwestern part of Japan, bringing with them metal technologies and rice cultivation after the end of the Jomon period.1, 2, 3, 4

After the beginning of the subsequent Aeneolithic Yayoi period, the mixing of the indigenous Jomon population and the immigrant post-Jomon populations progressed.1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Skeletal remains of the immigrant post-Jomon populations show a marked difference in morphological characteristics from those of the Jomon population, along with a closer similarity to the East-Asian populations and the post-Jomon Japanese population. The immigrant post-Jomon populations and their descendants have contributed considerably to the formation of the majority of the modern Japanese population.2, 5, 6, 8, 12, 13

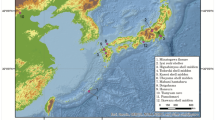

The immigrant post-Jomon populations (the immigrant Yayoi populations) were mainly distributed in northern Kyushu and southwestern Honshu in the Yayoi period. Many northern Kyushu Yayoi sites, most of which existed from the middle to late phases of the Yayoi period, are located on the inland plains of northern Kyushu (Figure 1). By contrast, most of the southwestern Honshu Yayoi sites, which existed from the early to middle phases of the Yayoi period, are located on the northwest coast of the southwestern end of Honshu. The most representative burial site of the southwestern Honshu Yayoi sites is the Doigahama site (Figure 1).

As to the regional differences in the immigrant Yayoi populations, there are many differences in the social and osteomorphological characteristics between the northern Kyushu Yayoi populations and the Doigahama Yayoi population. The lifestyle of the northern Kyushu Yayoi populations is believed to have differed from that of the Doigahama Yayoi population. The northern Kyushu Yayoi populations subsisted mainly on rice agriculture, whereas the Doigahama Yayoi population survived mainly by fishing and gathering.14 In addition, there is a great difference in the funerary customs between the northern Kyushu and Doigahama sites. Most of the skeletons at the sites in northern Kyushu were buried in jar coffins (Kamekan), but this burial style was not found at the Doigahama site, where stone coffins (Sekikan) and pits (Dokoubo) are common.15 In addition, many osteomorphological studies have been carried out on the skeletal remains from the sites in northern Kyushu and Doigahama.3, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Dodo et al.3 reported, on the basis of cranial nonmetric traits, that the protohistoric and historic Japanese were more closely related to the northern Kyushu Yayoi populations than to the Doigahama Yayoi population. These differences between the northern Kyushu sites and the Doigahama site provide us with important information for investigating the regional variations in the immigrant Yayoi populations and the influence of the immigrant Yayoi populations on the formation of the modern Japanese population.

At present, it is necessary to weigh new findings from human genetic studies with data from traditional fields of study, such as archeology and anatomy, using an interdisciplinary and integrated approach to clarify anthropological questions. Until the late 1970s, it was difficult to analyze small quantities of DNA extracted from ancient human remains. In the 1980s, as a result of the development of the PCR technique, it became possible to amplify small quantities of DNA samples.22, 23 Subsequently, this method of DNA amplification has been widely used for analyzing the kinships and phylogenetic characteristics of ancient human remains.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33

In Japan, DNA extracted from ancient human remains was first analyzed in the late 1980s. Using molecular biological methods, kinship and phylogenetic analyses of ancient human remains were carried out.34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Analyses of DNA from the Yayoi period were carried out mainly on skeletal remains from northern Kyushu.35, 36, 37 By contrast, analysis of DNA from the Doigahama site has not yet been carried out.

In this study, we analyzed mtDNA extracted from the Doigahama Yayoi population to examine its genetic structure. To outline the genetic structure of the Doigahama Yayoi population, a phylogenetic network was constructed from the mtDNA sequence types. On the basis of the phylogenetic network, six radiation groups were identified, and the frequency distributions of these radiation groups in the Doigahama Yayoi population were compared with those of the northern Kyushu Yayoi populations, the ancient Chinese populations and the modern Japanese population. In addition, we discuss the consistency between the molecular genetic data and the osteomorphological and archeological data, as discussed comprehensively by Oota et al.,37 Sato et al.43 and others.

In addition, we examined some interesting kinships among the individuals buried at the Doigahama site. By analyzing the funerary custom at the archeological site, we can clarify a part of the social structure of the ancient population. Archeological and morphological evidence has often been used to estimate the kinships of ancient human skeletal specimens.44, 45, 46, 47, 48 However, it is difficult to examine the kinship with accuracy based on only morphological evidence. In this study, DNA analyses on the remains, which have involved some interesting data in previous archeological and morphological studies, were carried out to investigate the relationship between burial style and kinships at the Doigahama site.

Materials and methods

Samples

More than 300 Yayoi skeletal remains were excavated from the Doigahama site between 1953 and 2000. The preservation of the skeletal remains was relatively good for most of the specimens. However, as the osteomorphological study of the skeletal remains from the Doigahama site is still underway, the number of samples available for DNA analysis is limited. In this study, we could use only 14 skeletal remains that were stored at the Doigahama site anthropological museum (Table 1). We analyzed the hypervariable (HV) region I of the control region in the mtDNA that was extracted from the specimens.

Contamination precautions

During each step of the handling of the samples, precautions were taken to minimize the risk of contamination and also to detect any potential contamination.49, 50, 51

The equipment used (dental drills, drill tips, mills and pipettes) and the bench were treated with a DNA contamination removal solution (DNA-OFF, TaKaRa, Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Shiga, Japan and 12% liquid sodium hypochlorite) and with ultraviolet (UV) irradiation. The disposable equipment (tubes and filtered pipette tips) was irradiated with UV rays. The samples were always handled by researchers wearing gloves, face masks, laboratory coats and caps.

To detect any potential contamination, extraction and amplification blanks were used as negative controls, and the sequence types of individuals who were involved in the study were defined by using fingernail and hair follicle samples. In addition, DNA extraction that included the cutting of bone samples was independently performed at least twice, and at least three PCR amplifications were performed for each extract to assess the reproducibility of the results.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from bone samples (Table 1). Samples were soaked in a 12% liquid sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 min, washed several times with distilled water and then allowed to air dry. The outer surface of the samples was removed at a depth of 1−2 mm using a dental drill. The samples were then washed with distilled water and allowed to air dry. The dried samples were exposed to UV irradiation for 15 min. Next, the samples were frozen with liquid nitrogen, and then pulverized in a mill (Cryo-Press CP-50W, Microtech Nichion, Funabashi, Chiba, Japan). DNA was extracted from ∼0.4 g of the pulverized sample using the Geneclean Kit For Ancient DNA (MP Biomedicals United States, Solon, OH, USA).

DNA amplification

A primer set was designed to amplify a segment, HVI, which has been described in previous studies involving mtDNA from ancient human remains in Japan.36, 37, 40, 41, 42, 52 Primer MT1 corresponds to the HVI segment (nucleotide position (n.p.) 16185−16439 of the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS)) (Table 2).

PCR amplifications were performed in 20 μl of the reaction mixture containing 1−2 μl of the ancient DNA extract, 0.2 μl (1 Unit) of Taq DNA polymerase (Ex Taq, TaKaRa), 2 μl of 10 × Ex Taq buffer, 1.6 μl of dNTP mixture, 0.04 μl (100 pmol μl−1) of each primer and 1 μl of DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide). The PCR reaction mixture was treated with 0.2 μl Uracil N-glycosylase (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) to excise the uracil that resulted from the hydrotic deamination of cytosine. DNA is decayed by many environmental factors after the death of an organism. This is referred to as postmortem DNA damage and can generate miscoding lesions in ancient DNA analyses. Hydrotic deamination of cytosine is considered to be one of the major causes of postmortem DNA damage.53, 54, 55 The amplification of DNA was performed under the following conditions: 36 °C for 10 min and 94 °C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 52 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 4 min.

DNA analysis

The PCR products were checked on a 2.5% agarose gel and purified using the ExoSAP-IT reagent (GE Healthcare Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ, USA). A set of primers (Seq MT1) was designed for sequencing; primer set Seq MT1 (L16236 and H16350) was used to sequence the HVI segment (Table 2). Sequencing reactions were performed using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit v3.1 (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The sequencing reaction products were analyzed using a Genetic Analyzer 3100 system (Applied Biosystems). The sequences from each region not containing primer regions were compared with the rCRS.56

Results and Discussion

In all, 13 of the 14 specimens were successfully amplified and sequenced for the HVI (16204–16419) segment (Table 3). Unfortunately, mtDNA obtained from the fourteenth specimen, identified as individual no. 88B, could not be amplified. As the sequence types of individuals who were involved in this study differed from those of the ancient specimens, the possibility of modern DNA contamination was considered low.

Among the skeletal remains, five individuals, nos 1301, 1405, 1406, 1903 and 88A, shared the same sequence type for the HVI segment. No nucleotide difference was recognized in HVI. Three other individuals, nos 1, 124 and 1601, also shared the same sequence type for the HVI segment. Among these individuals, T → C substitution was discovered at the 16209 position (16209T → C) in HVI. Consequently, six types of mtDNA sequences containing two of the above-mentioned types were recognized.

A homology search (BLAST search) was conducted using the mtDNA data samples obtained from the East-Asian populations in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) (Table 4). Only individual no. 1305 shared the same HVI sequence type with the modern mainland Japanese population.57, 58 The other individuals (excluding no. 913) shared the same HVI sequence type with a small percentage of the East-Asian populations.59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72

The sequence type of individual no. 913 did not correspond to that of the modern East-Asian populations. This result might be caused by postmortem DNA damage. However, as described above, the PCR reaction mixture was treated with Uracil N-glycosylase so as to excise uracil resulting from the hydrotic deamination of cytosine. The sequence type, which was not observed in the modern East-Asian populations, might have become extinct as a result of the genetic drift. In addition, the sequence type might be found through further analyses of past or modern East-Asian populations.

Phylogenetic analysis based on frequency distributions of DNA sequence types

The control region of mtDNA is often used for phylogenetic analysis because it is known as the region for which the evolutionary rate is several times higher than the coding region of mtDNA.73, 74 Many previous studies have been carried out on the control region sequence types of ancient populations that existed geographically close to the Doigahama Yayoi population, such as the northern Kyushu Yayoi and the ancient Chinese populations.52, 75, 76, 77 In this study, we analyzed the control region for examining the genetic structure of the Doigahama Yayoi population. As a preliminary analysis of the phylogenetic relationships of the Doigahama Yayoi population, the HVI sequence types obtained in this study were compared with those of the northern Kyushu Yayoi, modern Japanese and ancient Chinese populations that have previously been reported by other researchers, and a phylogenetic network was constructed to outline the phylogenetic characteristics of the Doigahama Yayoi population.

The HVI segments from the 13 Doigahama Yayoi specimens were added to the phylogenetic reference network constructed from the HVI segments of 1298 modern Asian and circum-Pacific individuals.76 The segments from the 35 specimens from the Kuma-Nishioda Yayoi site in northern Kyushu52 and 50 modern Japanese specimens57 were added as objects of comparison in the Japanese archipelago. Moreover, segments from 13 specimens from the 2500-year-old Linzi population (Shandong province, China)77 and 34 specimens from the 2000-year-old Linzi population75 were added as East-Asian populations contemporary with the Yayoi populations (Figure 2).

A phylogenetic network constructed from sequence types of hypervariable region I (HVI). Large circles denote backbone types 1, 3, 7, 9, 13, 25, 113, 138 and 173.76 The numbers on the branches are the nucleotide positions where base substitutions have occurred (add 16 000 to these numbers to obtain the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS)). • Denotes sequence types for the 2500-year-old Linzi population.77  Denotes sequence types for the 2000-year-old Linzi population.37 ○Denotes sequence types for the modern Japanese population.57

Denotes sequence types for the 2000-year-old Linzi population.37 ○Denotes sequence types for the modern Japanese population.57  Denotes sequence types for the Kuma-Nishioda Yayoi population.52

Denotes sequence types for the Kuma-Nishioda Yayoi population.52  Denotes sequence types for the Doigahama Yayoi population (present study). The numbers next to the small circles indicate the number of individuals in the sequence type.

Denotes sequence types for the Doigahama Yayoi population (present study). The numbers next to the small circles indicate the number of individuals in the sequence type.

On the basis of the phylogenetic reference network, six radiation groups were identified. Group I was characterized by n.p.16223C → T, without n.p.16362T → C. Group II was characterized by n.p.16362T → C, without n.p.16319G → A. Group III was characterized by base substitutions at n.p.16223, 16319 and 16362. Group IV was characterized by no nucleotide difference at n.p.16217, n.p.16223, n.p.16304, n.p.16319 and n.p.16362. Group V was characterized by n.p.16217T → C, without nucleotide difference at n.p.16223 and 16362. Group VI was characterized by n.p.16304T → C, without nucleotide differences at n.p.16223 and n.p.16362.

With regard to the Doigahama Yayoi specimens, only 1 individual belonged to group I; the other 12 individuals belonged to group IV. In all, 5, 2, 1, 21, 1 and 3 individuals from the 2500-year-old Linzi site belonged to groups I, II, III, IV, V and VI, respectively. For the individuals from the 2000-year-old Linzi site, 3, 4, 1 and 5 individuals belonged to groups I, II, V and VI, respectively. A total of 34 individuals and 1 individual from the Kuma-Nishioda Yayoi site belonged to groups I and V, respectively. In the modern Japanese population, 21, 21, 1, 3 and 4 individuals belonged to groups I, II, IV, V and VI, respectively.

The frequency distributions of six radiation groups in the Doigahama Yayoi and other populations are shown in Figure 3. We compared the frequency distributions of radiation groups in the Doigahama Yayoi population with those of the Kuma-Nishioda Yayoi population (one of the northern Kyushu Yayoi populations). The Doigahama Yayoi population showed a high frequency for group IV (92%), whereas the Kuma-Nishioda Yayoi population showed a high frequency for group I (97%).

There is another important study on the Takuta-Nishibun Yayoi population in northern Kyushu: Oota et al.37 analyzed the HVI segments (n.p.16224–n.p.16391) of 14 remains from the Takuta-Nishibun site. As two informative sites (n.p.16217 and n.p.16223), which were used to determine the radiation groups I, IV and V, were not analyzed in their study, the data collected from the Takuta-Nishibun Yayoi population were not added to the phylogenetic network in this study. As the sequence type (n.p.16362T → C, without base substitution at n.p.16319) was found in 9 of the 14 individuals from the Takuta-Nishibun Yayoi population, these individuals belonged to group II (64%). Consequently, the Takuta-Nishibun Yayoi population might show a high frequency for group II. In addition, their study showed that many of the mtDNA sequence types from the Takuta-Nishibun Yayoi population belonged in the same cluster with those of the modern Japanese population.37

The modern Japanese population showed high frequencies for groups I (42%) and II (42%). The northern Kyushu Yayoi populations also showed high frequencies for these groups. In contrast, the Doigahama Yayoi population had a high frequency for group IV, for which the modern Japanese population showed a low frequency (2%). These findings suggest that the Doigahama Yayoi population might have contributed less to the modern Japanese gene pool than to the northern Kyushu Yayoi population. As described in the ‘Introduction’ section, it is suggested that there were many differences between the northern Kyushu Yayoi populations and the Doigahama Yayoi population in several morphological and archeological studies.3, 14, 15, 18, 19 The genetic results of this study support these previous morphological and archeological studies.

The 2500-year-old Linzi population (group I: 15%, group II: 6%, group III: 3%, group IV: 65%, group V: 3%, group VI: 9%) resembled the 2000–2300-year-old Doigahama Yayoi population with respect to the high frequency for group IV. It was suggested that there were phylogenetically similar populations in China and Japan during the ancient period, from 2500 to 2000 years ago.

On the other hand, the low frequencies of group IV in the modern East-Asian populations were reported by Wang et al.77 In addition, their study indicated that the 2500-year-old Linzi populations showed less genetic resemblance to modern East-Asian populations.77 These findings suggest that more than one ancient population, which had different phylogenetic characteristics from modern East-Asian populations, existed in the past in East Asia. This is informative for estimating the phylogenetic relationships among ancient East-Asian populations. The resemblance between the ancient populations in China and Japan might support the notion that ancient China is the place from which the Doigahama Yayoi population immigrated. The amount of genetic data is still not sufficient enough to discuss the phylogenetic relationships among the ancient East-Asian populations. Further genetic studies are required to shed light on the phylogenetic relationships among the ancient East-Asian populations.

Kinship analyses

Kinship relationships were examined by focusing on particularly interesting individuals in the Doigahama Yayoi population who were successfully sequenced in this study. Two categories of interest were identified. The first category involved two cases of vicinal burials (skeletons that were buried side by side) (nos 1405 and 1406 and nos 1903 and 1904, respectively). The second category involved skeletons that were believed to have had the same social role in the Doigahama population (nos 1 and 124).

As the present analysis covered only segments from the control region, these results are insufficient to determine the presence of kinship. Furthermore, if the population has small variability of the mtDNA sequence types, a concordance of sequence types does not always show the presence of a kinship. For these reasons, in this study, the possibility of a maternal kinship was examined using DNA analyses for the individuals, for which the possibility of kinship has been suggested in the archeological findings.

Cases of vicinal burials

Case A: nos 1405 and 1406

On the basis of the morphological evidence, both individuals were estimated to be middle-aged males. It is believed that no. 1405 was buried soon after no. 1406 (Table 1).78 They were buried opposite each other. No. 1405 was buried in a face-up position that was common at the Doigahama site, whereas no. 1406 was buried in a facedown position that was extremely rare at the Doigahama site.

Ritual tooth extraction was observed in both skulls. The teeth extracted from each individual differ. In no. 1405, the bilateral upper and lower lateral incisors were extracted, whereas in no. 1406, the bilateral upper canines were extracted. This custom has been observed frequently in skulls from ancient Japan during the Jomon and Yayoi periods. Harunari79 and Nakahashi80 have suggested that the type of tooth extraction might depend on differences in ancestry (and/or origin).

In the osteomorphological study, the skeletons differed not only by the size of the neurocranium but also in the length of the femur. In particular, the estimated body height differed greatly for each skeleton (no. 1405: 164.78 cm; no. 1406: 158.01 cm).81 There was little morphological similarity between these two individuals, although it is noted that the skeletal measurements of the femur and cranium show a family resemblance.82 As a whole, although the skeletons were buried side by side, the archeological and morphological findings were different.

The mtDNA analysis showed that both skeletons contained the same sequence types (Table 3). As the analysis covered only segments of the control region, this result is insufficient to determine the presence of kinship, but it suggests that the skeletons might have been buried side by side on the basis of their maternal lineage. As their burial times were relatively close to one another, a high level of consanguinity was considered likely; for example, they were believed to be brothers, or nephew and uncle, or cousins.

In this case, although many findings, such as burial positions, tooth extraction types and osteomorphological features, differed between these two individuals, the mtDNA sequences showed that the skeletons might be related along a maternal lineage. The differences in the archeological and morphological findings between the specimens might indicate some relationships other than the maternal lineage.

Case B: nos 1903 and 1904

According to the excavator's report, no. 1903 was determined to be 4-years-old, and no. 1904 was 15.83 It has been estimated that no. 1903 was buried after no. 1904 (Table 1).84 Ritual tooth extraction was not observed in either skull, and there was no overt difference in the archeological findings between them. Moreover, as there is a large age difference between them, and the skeletons were in an immature stage, it was difficult to make a comparison using skeletal measurements. It has been suggested that the skeletons might have been buried on the basis of kinship because they were buried side by side.

Their mtDNA sequence types were different. In no. 1903, there was no nucleotide difference in HVI. On the other hand, in no. 1904, a 16266 C → T base substitution was observed in HVI. These results indicate that the skeletons were not related along the maternal lineage.

Using molecular biological methods, Adachi et al.40, 42 reported kinship analysis for skeletal specimens found in double burials excavated from the Jomon site. However, as there are many different factors, such as period, geographical region and burial style, between their study and our study, it is difficult to compare the results. The association between burial style and kinship is not entirely clear for individuals buried vicinally, as indicated by Cases A and B in this study. To clarify this association, it is necessary to accumulate more data with regard to the kinship between individuals and to analyze the data obtained from archeological and morphological findings.

In addition, to identify kinship relationships, it is necessary to examine the paternal as well as the maternal lineage. Many researchers have analyzed autochromosomes extracted from ancient human remains and have used them to examine the paternal lineage.30, 31, 33, 35 However, in general, ancient DNA is often highly damaged, which makes it rather difficult to analyze. It is hoped that a highly accurate and simple technique for ancient DNA analysis will be developed.

Adult skeletons that were believed to have the same social role in the Doigahama Yayoi population

The skeletal remains of individual no. 1, which were excavated along with a piece of cormorant skeleton, were estimated to be those of a middle-aged female. This was the only skeleton excavated along with bird bones from the Doigahama site. Individual no. 124, estimated to be a middle-aged adult male, was excavated with 12 stone arrow tips and 2 arrow tips made of shark teeth. Moreover, the skeleton had two bracelets made of cone shells (made from Tricornis latissimus, an organism that lives in the subtropical and tropical areas of the Pacific Ocean) on his right arm.

Owing to this unique burial style, it was suggested that these skeletons might have been those of shamans (or leaders) among the Doigahama Yayoi population.85 In addition, individual no. 1 showed ritual tooth extraction of the bilateral upper and lower lateral incisors. For no. 124, as the facial bones of the skull were fragmented, it was difficult to examine the whole of the alveolar bone. However, alveolar closure was observed in the right upper lateral incisor. Thus, it is possible that the lateral incisor was extracted from the skeleton during ritual tooth extraction. In this case, teeth extraction types might correspond with one anther. The skeletons were buried relatively close to each other, but not side by side. For this reason, these skeletons have never been examined in terms of their kinships.

mtDNA sequencing showed that the skeletons shared the same sequence types (Table 3). In both skeletons, a base substitution of 16209T → C was observed. Thus, the skeletons might have been related through a maternal lineage. These results suggest that the role of shaman might have been passed down through the maternal line in the Doigahama Yayoi population.

Kurosaki et al.35 reported that the two skeletons believed to be those of shamans or leaders at the Hanaura Yayoi site in northern Kyushu were not related along maternal and paternal lineages. These results differed from those of our study. These facts might suggest some regional differences in social structures during the Yayoi period.

Conclusions

We analyzed the segments of control regions in mtDNA extracted from 14 ancient human skeletal remains that were excavated from the Doigahama site. We amplified and sequenced mtDNA control regions from 13 of the 14 specimens. The HVI sequence types from specimens excavated from the Doigahama site were compared with those of the modern Japanese population, the northern Kyushu Yayoi populations and the ancient populations of the Shandon province of China. Although the analysis is preliminary, the results suggest that the Doigahama Yayoi population might have contributed less to the modern Japanese gene pool than the northern Kyushu Yayoi population.

Moreover, we examined the kinship among particularly interesting individuals in the Doigahama site. Our results showed that the two adult skeletons (nos 1405 and 1406) buried vicinally might have been related along a maternal lineage, but the two juvenile skeletons (nos 1903 and 1904) buried vicinally were not related. In cases of vicinal burials, individuals may or may not be related along a maternal lineage and it can be concluded that the styles of vicinal burials might have been influenced by many complex factors, such as paternal lineages, periods and geographical regions. In addition, our results showed that the adult skeletons (nos 1 and 124) that were believed to be those of shamans (or leaders) in the Doigahama Yayoi population might have been related along a maternal lineage, although the skeletons did not receive vicinal burials. This fact suggests that their crucial social roles might have been inherited along a maternal lineage in the Doigahama Yayoi population.

References

Hanihara, K. Dual structure model for the population history of the Japanese. Jpn Rev. 2, 1–33 (1991).

Kanaseki, T. The question of the Yayoi people. in Symposium on Japanese Archaeology Vol. 4 (ed Sugihara, S.) 238–252 (Kawade Shobo, Tokyo, 1956) (in Japanese).

Dodo, Y., Ishida, H. & Saitou, N. Population history of Japan: a cranial nonmetric approach. in The Evolution and Dispersal of Modern Humans in Asia (eds Akazawa, T., Aoki, K. & Kimura, T.) 479–492 (Hokusen-sha, Tokyo, 1992).

Yamaguchi, B. Skeletal morphology of the Jomon people in Japanese as a Member of the Asian and Pacific Populations (ed Hanihara, K.) 53–63 (International Research Center for Japanese Studies. Nan’un-do, Kyoto, 1992) (in Japanese).

Turner, C. G. II. Late Pleistocene and Holocene population history of East Asia based on dental variation. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 73, 305–321 (1987).

Turner, C. G. II. Major features of sundadonty and sinodonty, including suggestions about East Asian microevolution, population history, and late Pleistocene relationships with Australian Aboriginals. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 82, 295–317 (1990).

Brace, C. L., Brace, M. L. & Leonard, W. L. Reflections on the face of Japan: a multivariate craniofacial and odontometric perspective. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 78, 93–113 (1989).

Brace, C. L. & Hunt, K. D. A nonracial craniofacial perspective on human variation: A(ustralia) to Z(uni). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 82, 341–360 (1990).

Dodo, Y. & Ishida, H. Population history of Japan as viewed from cranial nonmetric variation. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon. 98, 269–287 (1990).

Kozintsev, A. Ainu, Japanese, their ancestors and neighbours: cranioscopic data. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon. 98, 247–267 (1990).

Kozintsev, A. Prehistoric and recent populations of Japan: multivariate analysis of cranioscopic data. Arctic Anthropol. 29, 104–111 (1992).

Lahr, M. M. The Evolution of Modern Human Diversity: A Study of Cranial Variation (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996).

Ossenberg, N. S., Dodo, Y., Maeda, T. & Kawakubo, Y. Ethnogenesis and craniofacial change in Japan from the perspective of nonmetric traits. Anthropol. Sci. 114, 99–115 (2006).

Matsushita, T. Sharekoube ga kataru. Nihonnjin no ruutsu to mirai. [Talking by crania. Roots and future of the Japanese.] (Nagasaki Shinbunsha, Nagasaki, 2001) (in Japanese).

Aikens, C. M. & Higuchi, T. Prehistory of Japan (Academic Press, New York, 1982).

Ushijima, Y. The human skeletal remains from the Mitsu site, Saga prefecture, a site associated with the “Yayoishiki” period of prehistoric Japan. Jinruigaku Kenkyu 1, 273–303 (1954) (in Japanese).

Zaitsu, H. On the limb bones of certain Yayoi-period ancients, excavated at the Doigahama site, Yamaguchi prefecture. Jinruigaku Kenkyu 3, 320–349 (1956) (in Japanese).

Kanaseki, T., Nagai, M. & Sano, H. Craniologic studies of the Yayoi-period ancients, excavated at the Doigahama site, Yamaguchi prefecture. Jinruigaku Kenkyu 7 (Suppl.), 1–36 (1960) (in Japanese with English summary).

Kanaseki, T. The question of the Yayoi people. in Symposium on Japanese Archaeology Vol. 3 (ed Wajima, S.) 460–471 (Kawade Shobo, Tokyo, 1966) (In Japanese).

Matsushita, T., Wakebe, T., Sakuma, M., Nakatani, S., Naito, Y. & Ishida, H. An anthropological study on the human skeletons of Yayoi period excavated from Takuta-Nishibun Shell Mound, Saga prefecture. Kaibogaku Zasshi 59, 411 (1984) (in Japanese).

Nakahashi, T. & Nagai, M. Morphological characteristics of the Yayoi people. in Study of Yayoi Culture Vol. 1 (eds Nagai, M., Kanaseki, H., Nasu, T. & Sahara, M.) 23–51 (Yuzankaku shuppan, Tokyo, 1989) (in Japanese).

Saiki, R. K., Scharf, S., Faloona, F., Mullis, K. B., Hors, G. T., Erlich, H. A. et al. Enzymatic amplification of beta-globin genomic sequences and restriction site analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Science 230, 1350–1354 (1985).

Saiki, R. K., Gelfand, D. H., Stoffel, S., Scharf, S. J., Higuchi, R., Horn, G. T. et al. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science 239, 487–491 (1988).

Pääbo, S., Gifford, J. A. & Wilson, A. C. Mitochondrial DNA sequences from a 7000-year old brain. Nucleic Acid. Res. 16, 9775–9787 (1988).

Stone, A. C. & Stoneking, M. Ancient DNA from a pre-Columbian Amerindian population. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 92, 463–471 (1993).

Stone, A. C. & Stoneking, M. Analysis of ancient DNA from a prehistoric Amerindian cemetery. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 354, 153–159 (1999).

Handt, O., Hoss, M., Krings, M. & Pääbo, S. Ancient DNA: methodological challenges. Experientia 50, 524–529 (1994).

Krings, M., Stone, A. C., Schmitz, R. W., Krainitzki, H., Stoneking, M. & Pääbo, S. Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans. Cell 90, 19–30 (1997).

Krings, M., Capelli, C., Tschentscher, F., Geisert, H., Meyer, S., von Haeseler, A. et al. A view of Neandertal genetic diversity. Nat. Genet. 26, 144–146 (2000).

Keyser, C., Crubezy, E. & Ludes, B. Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis of a 2000-years-old necropolis in the Egyin Gol valley of Mongolia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73, 247–260 (2003).

Ricaut, F., Keyser, C., Cammaert, L., Crubezy, E. & Ludes, B. Genetic analysis and ethnic affinities from two Scytho-Siberian skeletons. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 123, 351–360 (2004).

Ricaut, F., Kolodesnikov, S., Keyser, C., Alekseev, A., Crubezy, E. & Ludes, B. Molecular genetic analysis of 400-year-old human remains found in two Yakut burial sites. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 129, 55–63 (2006).

Clisson, I., Keyser, C., Francfort, H. P., Crubezy, E., Samashev, Z. & Ludes, B. Genetic analysis of human remains from a double inhumation in frozen kurgan in Kazakhstan (Berel site, Early 3rd Century BC). Int. J. Legal Med. 116, 304–308 (2002).

Horai, S., Hayasaka, K., Murayama, K., Wate, N., Koike, H. & Nakai, N. (1989) DNA amplification from ancient human skeletal specimens and their sequence analysis. Proc. Jpn Acad. 65 (Ser. B), 229–233 (1989).

Kurosaki, K., Matsushita, T. & Ueda, S. Individual DNA identification from ancient human remains. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 53, 638–643 (1993).

Shinoda, K. & Kunisada, T. Analysis of ancient Japanese society through mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 4, 294–297 (1994).

Oota, H., Saitou, N., Matsushita, T. & Ueda, S. A genetic study of 2000-year-old human remains from Japan using mitochondrial DNA sequences. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 98, 133–145 (1995).

Shinoda, K., Matsumura, H. & Nishimoto, T. Genetical and morphological analysis on kinship of Nakazuma Jomon people using mitochondrial DNA and tooth crown measurement. Zoo-archaeology 11, 1–21 (1998) (in Japanese with English summary).

Shinoda, K. & Kanai, S. Intracemetery genetic analysis at the Nakazuma Jomon site in Japan by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Anthropol. Sci. 107, 129–140 (1999).

Adachi, N., Dodo, Y., Ohshima, N., Doi, N., Yoneda, M. & Matsumura, H. Morphologic and genetic evidence for kinship of juvenile skeletal specimens from a 2000 years-old double burial of Usu-Moshiri site, Hokkaido, Japan. Anthropol. Sci. 111, 347–363 (2003).

Adachi, N., Umetsu, K., Takigawa, W. & Sakaue, K. Phylogenetic analysis of the human ancient mitochondrial DNA. J. Archaeol. Sci. 31, 1339–1348 (2004).

Adachi, N., Suzuki, T., Sakaue, K., Takigawa, W., Ohshima, N. & Dodo, Y. Kinship analysis of the Jomon skeletons unearthed from a double burial at the Usu-Moshiri site, Hokkaido, Japan. Anthropol. Sci. 114, 29–34 (2006).

Sato, T., Amano, T., Ono, H., Ishida, H., Kodera, H., Matsumura, H. et al. Origins and genetic features of the okhotsk people, revealed by ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis. J. Hum. Genet. 52, 618–627 (2007).

Hanihara, K., Yamaguchi, A. & Mizoguchi, Y. Statistical analysis on kinship among skeletal remains excavated from a Neolithic site at Uwasato, Iwate Prefecture. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon 91, 49–68 (1983) (in Japanese with English summary).

Doi, N., Tanaka, Y. & Funakoshi, K. An approach on kinship among skeletal remains from Uenoharu tunnel-tombs, Oita Prefecture. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon 93, 206 (1985) (in Japanese with English title).

Matsumura, H. & Nishimoto, T. Statistical analysis on kinship of Nakazuma Jomon people using tooth crown measurements. Zoo-archaeology 6, 1–17 (1996) (in Japanese with English summary).

Alt, K. W., Pichler, S., Vach, W., Klima, B., Vlcek, E. & Sedlmeier, J. Twenty-five thousand-year-old triple burial from Dolni Vestonice: an ice age family? Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 102, 123–131 (1997).

Formicola, V. & Buzhilova, A. P. Double child burial from Sunghir (Russia): pathology and inferences for upper Paleolithic funerary practices. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 124, 189–198 (2004).

Pääbo, S., Irwin, D. M. & Wilson, A. C. DNA damage promotes jumping between templates during enzymatic amplification. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 4718–4721 (1990).

Pääbo, S., Poinar, H., Serre, D., Jaenicke-Despres, V., Heber, J., Rohland, N. et al. Genetic analysis from ancient DNA. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38, 645–679 (2004).

Bouwman, A. S., Chilvers, E. R., Brown, K. A. & Brown, T. A. Brief communication: identification of the authentic ancient DNA sequence in a human bone contaminated with modern DNA. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 131, 428–431 (2006).

Shinoda, K. Ancient DNA analysis of skeletal samples recovered from the Kuma-Nishioda Yayoi site. Bull. Natl Sci. Mus. Ser. D 30, 1–8 (2004).

Gilbert, M. T., Willerslev, E., Hansen, A. J., Barnes, I., Rudbeck, L., Lynnerup, N. et al. Distribution patterns of postmortem damage in human mitochondrial DNA. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 32–47 (2003).

Gilbert, M. T., Hansen, A. J., Willerslev, E., Rudbeck, L., Barnes, I., Lynnerup, N. et al. Characterization of genetic miscoding lesions caused by postmortem damage. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 48–61 (2003).

Hofreiter, M., Jaenicke, V., Serre, D., von Haeseler, A. & Pääbo, S. DNA sequences from multiple amplifications reveal artifacts induced by cytosine deamination in ancient DNA. Nucleic Acid. Res. 29, 4793–4799 (2001).

Andrews, R. M., Kubacka, I., Chinnery, P. F., Lightowlers, R. N., Turnbull, D. M. & Howell, N. Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 23, 147 (1999).

Tanaka, M., Cabrera, V. M., Gonzalez, A. M., Larruga, J. M., Takeyasu, T., Fuku, N. et al. Mitochondrial genome variation in Eastern Asia and peopling of Japan. Genome Res. 14, 1832–1850 (2004).

Tajima, A., Hayami, M., Tokunaga, K., Juji, T., Matsuo, M., Marzuki, S. et al. Genetic origins of the Ainu inferred from combined DNA analyses of maternal and paternal lineages. J. Hum. Genet. 49, 187–193 (2004).

Irwin, J. A., Saunier, J. L., Strouss, K. A., Diegoli, T. M., Sturk, K. M., O’Callaghan, J. E. et al. Mitochondrial control region sequences from a Vietnamese population sample. Int. J. Legal Med. 122, 257–259 (2008).

Yao, Y. G., Lu, X. M., Luo, H. R., Li, W. H. & Zhang, Y. P. Gene admixture in the silk road region of China: evidence from mtDNA and melanocortin 1 receptor polymorphism. Genes Genet. Syst. 75, 173–178 (2000).

Yao, Y. G., Kong, Q. P., Bandelt, H. J., Kivisild, T. & Zhang, Y. P. Phylogeographic differentiation of mitochondrial DNA in Han Chinese. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 635–651 (2002).

Yao, Y. G., Nie, L., Harpending, H., Fu, Y. X., Yuan, Z. G. & Zhang, Y. P. Genetic relationship of Chinese ethnic populations revealed by mtDNA sequence diversity. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 118, 63–76 (2002).

Yao, Y. G., Kong, Q. P., Man, X. Y., Bandelt, H. J. & Zhang, Y. P. Reconstructing the evolutionary history of China: a caveat about inferences drawn from ancient DNA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 214–219 (2003).

Yao, Y. G., Kong, Q. P., Wang, C. Y., Zhu, C. L. & Zhang, Y. P. Different matrilineal contributions to genetic structure of ethnic groups in the silk road region in China. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 2265–2280 (2004).

Li, H., Cai, X., Winograd-Cort, E. R., Wen, B., Cheng, X., Qin, Z. et al. Mitochondrial DNA diversity and population differentiation in southern East Asia. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 134, 481–488 (2007).

Horai, S., Murayama, K., Hayasaka, K., Matsubayashi, S., Hattori, Y., Fucharoen, G. et al. mtDNA polymorphism in East Asian populations, with special rerferece to the peopling of Japan. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 59, 579–590 (1996).

Kong, Q. P., Yao, Y. G., Liu, M., Shen, S. P., Chen, C., Zhu, C. L. et al. Mitochondrial DNA sequence polymorphisms of five ethnic populations from northern China. Hum. Genet. 113, 391–405 (2003).

Kong, Q.-P., Yao, Y.-G., Sun, C., Bandelt, H.-J., Zhu, C.-L. & Zhang, Y.-P. Phylogeny of east Asian mitochondrial DNA lineages inferred from complete sequences. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73, 671–676 (2003).

Kong, Q. P., Bandelt, H. J., Sun, C., Yao, Y. G., Salas, A., Achilli, A. et al. Updating the East Asian mtDNA phylogeny: a prerequisite for the identification of pathogenic mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 2076–2086 (2006).

Yao, Y. G. & Zhang, Y. P. Phylogeographic analysis of mtDNA variation in four ethnic populations from Yunnan Province: new data and a reappraisal. J. Hum. Genet. 47, 311–318 (2002).

Hill, C., Soares, P., Mormina, M., Macaulay, V., Clarke, D., Blumbach, P. B. et al. A mitochondrial stratigraphy for Island Southeast Asia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80, 29–43 (2007).

Tajima, A., Sun, C. S., Pan, I. H., Ishida, T., Saitou, N. & Horai, S. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms in nine aboriginal groups of Taiwan: implications for the population history of aboriginal Taiwanese. Hum. Genet. 113, 24–33 (2003).

Aquadro, C. & Greenberg, B. Human mitochondrial DNA variation and evolution: analysis of nucleotide sequences from seven individuals. Genetics 103, 287–312 (1983).

Brown, W., George, M. & Wilson, A. Rapid evolution of animal mitochondrial DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 76, 1967–1971 (1979).

Oota, H., Saitou, N., Matsushita, T. & Ueda, S. Molecular genetic analysis of remains of a 2000-year-old human population in China—and its relevance for the origin of the modern Japanese population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 64, 250–258 (1999).

Oota, H., Saitou, N. & Ueda, S. A large-scale analysis of human mitochondrial DNA sequences with special reference to the population history of east Eurasian. Anthropol. Sci. 110, 293–312 (2002).

Wang, L., Oota, H., Saitou, N., Jin, F., Matsushita, T. & Ueda, S. Genetic structure of a 2500-year-old human population in China and its spatiotemporal changes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 1396–1400 (2000).

Arifuku, H. Tracking summary. In Report of the 14th Excavation Research at the Doigahama Site (eds Matsushita, T. & Arifuku, F.) 8–17 (Educational committee of Hohokucho, Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi, 1996) (in Japanese).

Harunari, H. The meaning of ritual tooth ablation. Q, Archaeol. Stud. 20, 25–48 (1973) (in Japanese).

Nakahashi, T. Ritual tooth-ablation in Doigahama Yayoi people. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon 98, 483–507 (1990) (in Japanese with English summary).

Matsushita, T. Ancient human skeletons from 14th excavation research at the Doigahama site, Yamaguchi prefecture. in Report of the 14th Excavation Research at the Doigahama Site (eds Matsushita, T. & Arifuku, F.) 24–50 (Educational committee of Hohokucho, Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi, 1996) (in Japanese).

Doi, N. Osteometrical study of genetic and environmental influence on the shape of the human skeleton: I. Intra-familiar resemblances in the skeletal morphology of the Kanaseki-family and other familial series. J. Anthrop. Soc. Nippon 99, 437–462 (1991) (in Japanese with English summary).

Matsushita, T., Matsushita, R., Isobe, M., Nakano, E. & Nakano, N. Ancient human skeletons from 19th excavation research at the Doigahama site, Yamaguchi prefecture. in Report of the 19th Excavation Research at the Doigahama site (eds Matsushita, T., & Furushou, H.) 18–46 (Doigahama site anthropological museum, Yamaguchi, 2002) (in Japanese).

Furushou, H. Relics and remains in Report of the 19th Excavation Research at the Doigahama Site (eds Matsushita, T. & Furushou, H.) 7–17 (Doigahama Site Anthropological Museum, Yamaguchi, 2002) (In Japanese).

Yamada, Y. Issue of the Doigahama site. in Report of the 17th Excavation Research at the Doigahama Site (ed Yamada, Y.) 28–33 (Educational committee of Hohokucho and Doigahama site anthropological museum, Yamaguchi, 1999) (in Japanese).

Tsuboi, K. & Kanaseki, H. Value of the Doigahama site. in Report of Conservation Management Plan in the Doigahama site 1–22 (Educational Committee of Hohokucho, Yamaguchi, 1978) (in Japanese).

Matsushita, T. Ancient human skeletons from 13th excavation research at the Doigahama site, Yamaguchi prefecture. in Report of the 13th Excavation Research at the Doigahama Site (ed Okayasu, Y.) 19–33 (Educational Committee of Hohokucho, Yamaguchi, 1995) (in Japanese).

Matsushita, T. Ancient human skeletons from 16th excavation research at the Doigahama site, Yamaguchi prefecture. in Report of the 16th Excavation Research at the Doigahama Site (ed Yamada, Y.) suppl. 24–50 (Doigahama Site Anthropological Museum, Yamaguchi, 1998) (in Japanese).

Acknowledgements

We express sincere gratitude to Dr K Umetsu, Yamagata University, for helpful suggestions regarding the mtDNA analyses. We also thank the members of the Forensic Science Laboratory, Nagasaki Prefectural Police Headquarters and the members of the Doigahama Site Anthropological Museum for their help in conducting this research. We also thank all those who kindly provided us with fingernail and hair follicle samples for the DNA contamination analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Igawa, K., Manabe, Y., Oyamada, J. et al. Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Yayoi period human skeletal remains from the Doigahama site. J Hum Genet 54, 581–588 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2009.81

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2009.81