Abstract

Plant domestication was a pivotal accomplishment in human history, but also led to a reduction in genetic diversity of crop species compared to their wild ancestors. How this reduced genetic diversity affected plant–microbe interactions belowground is largely unknown. Here, we investigated the genetic relatedness, root phenotypic traits and rhizobacterial community composition of modern and wild accessions of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) grown in agricultural soil from the highlands of Colombia, one of the centers of common bean diversification. Diversity Array Technology-based genotyping and phenotyping of local common bean accessions showed significant genetic and root architectural differences between wild and modern accessions, with a higher specific root length for the wild accessions. Canonical Correspondence Analysis indicated that the divergence in rhizobacterial community composition between wild and modern bean accessions is associated with differences in specific root length. Along the bean genotypic trajectory, going from wild to modern, we observed a gradual decrease in relative abundance of Bacteroidetes, mainly Chitinophagaceae and Cytophagaceae, and an increase in relative abundance of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria, in particular Nocardioidaceae and Rhizobiaceae, respectively. Collectively, these results establish a link between common bean domestication, specific root morphological traits and rhizobacterial community assembly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rhizosphere microbiome has a profound impact on plant health and growth by providing key functions involved in nutrient acquisition, abiotic stress tolerance and protection against pathogen infection (Mendes et al., 2011, 2013; Bulgarelli et al., 2013). Edaphic factors and plant genotype shape, to a certain extent, the composition and metabolic activities of the bacterial communities in the rhizosphere (Berg and Smalla, 2009; Bulgarelli et al., 2012; Lundberg et al., 2012; Philippot et al., 2013). The effects of the plant genotype on rhizosphere microbiome composition has been proposed to be, at least in part, mediated by quantitative and qualitative differences in root exudate composition (Lakshmanan et al., 2012; Badri et al., 2013; Carvalhais et al., 2013; Lebeis et al., 2015). Hence, the composition of a particular rhizosphere microbial assemblage is dependent on the plant species (Turner et al., 2013; Ofek et al., 2014) and even on the cultivar of a given plant species (Peiffer et al., 2013).

Plant domestication was essential to human history but also resulted in a significant reduction in genetic diversity of crop species as compared to their wild ancestors (Doebley et al., 2006). Whether this reduction in genetic diversity affected specific root morphological traits and microbial diversity and activity in the rhizosphere is still largely unknown. To date, a limited number of studies have indicated that rhizosphere microbiome assembly may have been affected in modern cultivars of plants as compared to their wild ancestors (Bulgarelli et al., 2015; Leff et al., 2016; Pérez-Jaramillo et al., 2016). In this context, wild relatives and also landraces have been proposed to provide valuable new insight into plant traits and genes associated with microbiome assembly, allowing an integral role of microbiome assembly in future plant breeding programs. For most economically important food crops, however, little knowledge is available on the impact of plant domestication on root traits and rhizosphere microbiome assembly. Here, we determined the genetic relatedness and root morphological traits of wild and modern accessions of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and analyzed their rhizosphere microbiome composition. Common bean is the most important legume crop for low-income farmers in Latin America and Africa (Broughton et al., 2003; Akibode and Maredia, 2011). Wild common bean originated in central Mexico and spread throughout Central and South America (Gepts, 1998; Bitocchi et al., 2012; Desiderio et al., 2013). This wide distribution led to geographical isolation of wild common bean and resulted in well-characterized genetic pools (Gepts and Bliss, 1985). A vast collection of available accessions, ranging from wild relatives to highly productive modern varieties, makes common bean a good model system to investigate the impact of domestication on root phenotypic traits and on rhizobacterial community composition of an economically important food crop. Furthermore, common bean and other leguminous plant species provide excellent experimental systems to study the intertwined relationships between nodulation and rhizosphere microbiome assembly (Zgadzaj et al., 2016).

In this study, we adopted the approach of ‘going back to the roots’ (Pérez-Jaramillo et al., 2016) and selected eight Colombian accessions of common bean, including wild relatives, landraces and modern cultivars and characterized their genetic relatedness by Diversity Array Technology (Jaccoud et al., 2001). Subsequently, the selected bean accessions were grown in agricultural soil collected from the highlands of Antioquia, Colombia. Colombian mountains are considered an important center of common bean diversification where wild and landraces of common bean from the two main genetic pools (Mesoamerican and Andean) can still be found in their natural habitats (Gepts and Bliss, 1986). The selected common bean accessions were subjected to phenotypic analyses of different root traits as well as rhizobacterial community analyses by 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing.

Materials and methods

Selection of common bean accessions and Colombian soil

Two wild, three landraces and three improved varieties (modern cultivars) of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) were selected based on the following characteristics: they belong to the Colombian Mesoamerican genetic pool; landraces and modern accessions are the same race, they exhibit the Mesoamerican phaseolin protein type; they originate from the same altitudinal range; and they have the same growth type (that is, climbing instead of bushy). The latter characteristic is the case for all selected accessions, except for accession G5773, which is a bushy commercial variety widely distributed and commonly used in Latin America and Africa. The seeds were kindly provided by the Genetic Resources Program at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture—CIAT—in Palmira, Colombia. The plant passport is given in Supplementary Table S1. The soil used in this study was collected from an agricultural field in the rural area of the municipality of El Carmen de Viboral (Antioquia—Colombia, 6°4′55″ N, 75°20′3″W). Common bean has been cropped in this region for decades and soil conditions are optimal for the growth of several common bean varieties. The soil was collected at three random sites in the field from a depth up to 30 cm, air dried, passed through a 2-mm mesh sieve to remove (plant) debris and stored for further use. Physicochemical analyses were performed in the Soil Science Laboratory from the National University of Colombia in Medellín, using standard procedures (Supplementary Table S2).

Genotyping of common bean accessions

The bean seeds were surface-sterilized and germinated on filter paper wetted with sterile tap water. After 2–5 days, germinated seeds were transferred to 500-ml pots filled with agricultural soil. For each bean accession, two seedlings were transplanted to a pot (1 pot per accession), arranged randomly in a growth chamber (25 °C, 16 h daylight) and watered every day. After 10 days, the youngest leaf of each plant was collected and DNA was isolated with the PowerPlant Pro DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The manufacturer’s instructions were followed and the yield and quality of the DNA was assessed via agarose gel electrophoresis and a Qubit 2.0 fluorimeter (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Genome profiling was performed using the complexity genome reduction method developed by Diversity Arrays Technology Pty Ltd (DArT P/L, Bruce, Australia) (Jaccoud et al., 2001). A proprietary analytical pipeline developed by DArT P/L was used to produce single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) tables; in total 10 732 SNPs were obtained. The SNP calling was performed using a custom R script (R Core Team, 2015) and after filtering, a total of 7527 SNPs were retained for further analysis.

Plant genetic diversity

An identity-by-state distance matrix was constructed in PLINK (v. 1.9) (Chang et al., 2015) and a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was created using the Phylip software package (v.3.695). For the quantitative assessment of the number of groups in the panel, a Bayesian clustering analysis was performed using the model-based approach implemented in the STRUCTURE software (Pritchard et al., 2000). This approach uses multi-locus genotypic data to assign individuals to clusters or groups (K) without prior knowledge of their population affinities and assumes loci in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. The software was ran considering K-values ranging from 1 to 6 (hypothetical number of groups) with an admixture model with correlated allele frequencies. Each run was implemented with 20 000 burnin iterations followed by 200 000 MCMC (Markov Chain Monte Carlo) iterations for accurate parameter estimates. Five independent runs for each K were performed. The number of genetic groups was estimated using the STRUCTURE HARVESTER software (Earl, 2012), by the Evanno criterion (Evanno et al., 2005). A multidimensional scaling analysis was also performed using PLINK. The inbreeding coefficient and occurrence of homozygous segments were computed using the commands ‘–het’ and ‘—homozyg’ in PLINK. The number of homozygous regions as well as their genomic locations was determined for each bean accession. Similarity of bean accession G51283K1 to the other accessions was determined by computing pairwise identity-by-state. The genome was divided into 109 blocks and within each block pairwise identity-by-state was calculated for all bean accessions; zero is completely different and two is completely identical. The accession G51283K1 was compared with the whole genomes of G22304 and landrace G23998 as wild accessions, with modern accessions G5773 and G51695 as modern accessions and with landrace G50632I1. All the genetic diversity and homozygosity analyses were performed in PLINK (v1.9) and visualized in R.

Root morphology

Seeds were germinated as described above and transferred to 3 l pots filled with the agricultural soil described above. Three plants per genotype were used. The plants were grown under ambient environmental conditions, with an average temperature of 25 °C and 12 h of daylight. When the V4 stage (3rd trifoliate leaf) was reached, the plants were carefully harvested and the root system was gently washed with tap water until no more soil particles were attached to the roots. Subsequently the entire root system was dyed with methylene blue, laid out on a Scanjet G4050 Scanner (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and scanned with a resolution of 600 dpi. The images were then analyzed with the software WinRHIZO (Regent Instruments Inc., Quebec, QC, Canada), and several root measurements were recorded (Supplementary Table S3). After scanning, roots were dried and root dry weight (rdw) measured. Subsequently, we computed the specific root length (SRL) using the equation rl/rdw, and the root tissue density (D), using the equation rdw/rv (Martín-Robles et al., 2015). These parameters were calculated, normality and homogeneity of variances were checked using Shapiro–Wilk test and Levene’s test, respectively, and one way ANOVA and post hoc tests were used to assess differences in root morphology between the bean accessions.

Rhizospheric soil collection and DNA isolation

The same procedure for seed germination described above was followed. Seedlings were transferred to 3l pots containing the agricultural soil. For each accession, four replicates were used with one plant per replicate pot. The plants were arranged randomly in a greenhouse with ambient environmental conditions with an average temperature of 25 °C and 12 h of daylight. Four pots with the same amount of soil but without plants were used as controls and served as bulk soil samples. Plants were collected at flowering to synchronize microbiome analyses for all accessions at the same phenological growth stage. Rhizospheric soil was collected according to the method of Lundberg et al. (2012). Briefly, the entire root system was sampled from the pots, soil loosely attached to the roots was removed and subsequently the entire root system was divided in three parts and each was transferred to a 15 ml tube containing 5 ml of LifeGuard Soil Preservation Solution (Mo Bio Laboratories). The tubes were vigorously shaken, the roots were removed and at least 1 g (wet weight) of rhizospheric soil was recovered per sample for DNA isolation. For the bulk soils, approximately 1 g of soil was collected from each control pot and also submerged in 5 ml of LifeGuard solution. Root dry weight, number of days to reach flowering and the total numbers of nodules per root system were scored. To obtain rhizospheric DNA, a RNA PowerSoil DNA Elution Accessory Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions after a previous step for RNA extraction and elution with a RNA PowerSoil Total RNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories). Each obtained DNA sample was then cleaned with the PowerClean DNA Clean-Up Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories). Agarose gel electrophoresis and a ND1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) were used to check DNA yield and quality. DNA samples were stored at −80 °C until further use.

16S rRNA amplicon sequencing

The DNA extracted from the rhizosphere was used for amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA, targeting the variable V3-V4 regions (Forward Primer=5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′

Reverse Primer=5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) resulting in amplicons of approximately ~460 bp. Dual indices and Illumina sequencing adapters using the Nextera XT Index Kit were attached to the V3–V4 amplicons. Subsequently, library quantification, normalization and pooling were performed and MiSeq v3 reagent kits were used to finally load the samples for MiSeq sequencing. For more info please refer to the guidelines of Illumina MiSeq System (Illumina, 2013).

The RDP extension to PANDASeq (Masella et al., 2012), named Assembler (Cole et al., 2014), was used to merge paired-end reads with a minimum overlap of 10 bp and at least a Phred score of 25. Primer sequences were removed from the per sample FASTQ files using Flexbar version 2.5 (Dodt et al., 2012). Sequences were converted to FASTA format and concatenated into a single file. All reads were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using the UPARSE strategy by de-replication, sorting by abundance with at least two sequences and clustering using the UCLUST smallmem algorithm (Edgar, 2010). These steps were performed with VSEARCH version 1.0.10 (Rognes et al., 2015), which is an open-source and 64-bit multi-threaded compatible alternative to USEARCH. Next, chimeric sequences were detected using the UCHIME algorithm implemented in VSEARCH (Edgar et al., 2011). All reads before the dereplication step were mapped to OTUs using the usearch_global method implemented in VSEARCH to create an OTU table and converted to BIOM-Format 1.3.1 (McDonald et al., 2012). Finally, taxonomic information for each OTU was added to the BIOM file by using the RDP Classifier version 2.10 (Cole et al., 2014). All steps were implemented in a Snakemake workflow (Köster and Rahmann, 2012). The OTU table was filtered using QIIME (1.9.1) custom scripts (Kuczynski et al., 2012). The Bacteria domain was extracted using the command split_otu_table_by_taxonomy.py and singletons, doubletons and chloroplast sequences were discarded with the command filter_otus_from_otu_table.py, obtaining a filtered OTU table for further analysis.

Rhizobacterial diversity and link with genotypic and root phenotypic traits

The alpha diversity was calculated using QIIME customs scripts. The command alpha_rarefaction.py was used to rarefy the OTU table to counts up to 50 000 reads. This was the lowest sequencing depth obtained from a sample and therefore used as a threshold for rarefaction and alpha diversity calculations (Gotelli and Colwell, 2001). The alpha_diversity.py command was applied to rarefied data and observed OTUs, Shannon, Chao1 and Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity metrics were obtained. One-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD were performed in R. For the Beta-diversity calculations, the entire filtered OTU table was used and normalized using the function cumNorm from the R package metagenomeSeq (v.1.12) (Paulson et al., 2016). We used a cumulative-sum scaling method, which calculates the scaling factors equal to the sum of counts up to a particular quantile to normalize the read counts in order to avoid the biases generated with current sequencing technologies due to uneven sequencing depth (Paulson et al., 2013). Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix was calculated and used it to build Principal Coordinate Analyses and Constrained Principal Coordinate Analysis constrained by phylogenetic group, that is, ancestral (A1 and A2) and modern (M1 to M5), using the function capscale retrieved from Vegan package (Oksanen et al., 2016) (v.2.3-2) and implemented in the Phyloseq package (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013) (v.1.10), both in R. The nonparametric adonis test was used to assess the percentage of variation explained by the Phylogenetic grouping along with its statistical significance. Permutational multivariate analyses of variance were performed to evaluate the significance of the constrained principal coordinate analyses, both retrieved from Phyloseq and Vegan packages. A Regularized Canonical Correlation Analysis was also performed in order to graphically depict whether the genetic make-up of the bean accessions correlates with their rhizobacterial community structures, using the R package CCA (González and Déjean, 2012). The function rcc was used, which is an extension of the Canonical Correlation Analysis to seek correlations between two data matrices. Subsequently, the function plt.cc was used to generate the plots. Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA, Canoco 5.0) was also conducted with a complete set of cumulative-sum scaling normalized counts of the 16S rRNA data and the root morphological traits SRL, Root Density, Root Dry weight and Number of Nodules. The adjusted explained variation and unrestricted permutations were calculated to determine the significant contribution of each variable and Bonferroni corrections were applied to adjust the P-values. Constrained ordinations were built using rhizobacterial phyla or families together with plant genotypic and root morphological traits as explanatory variables.

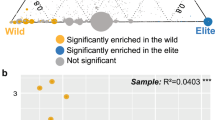

Species abundance distribution and differential abundance analysis

Species abundance distribution models were used to determine whether neutral or niche-based mechanisms were governing the bacterial assembly. We used the command Radfit from the R package Vegan to evaluate broken stick, pre-emption, log-normal, Zipf and Zipf–Mandelbrot rank abundance models and a zero-sum multinomial (ZSM) model using the TeTame2 software (Jabot et al., 2008). The comparison of the models fit was done based on the Akaike Information Criterion using the equation Akaike Information Criterion=−2 log-likehood+2 × npar (Mendes et al., 2014). Akaike Information Criterion values were compared, being the lowest selected as the best fit to the data (Dumbrell et al., 2010). To compare the differences in taxonomic composition and to assess whether some bacterial taxa were differentially abundant, we conducted a three-step analysis in which we assessed separately the read counts based on Phylum, Family and OTU level. For Phylum and Family level, custom R commands were used in order to aggregate all the reads according to the level chosen. For the OTU level analysis, the function calculateEffectiveSamples from the metagenomeSeq R package was applied to the filtered OTU table and features with less than the average number of effective samples in all features were removed. For the analysis at Phylum, Family and OTU level, we used normalized tables applying the cumulative-sum scaling normalization as described above. Then, a Zero-Inflated Gaussian Distribution Mixture Model was applied using the fitZig function from metagenomeSeq. With the coefficients from the model, we applied moderated t-tests between accessions using the makeContrasts and eBayes commands retrieved from the R package Limma (v.3.22.7) (Ritchie et al., 2015). Obtained P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction method. Differences in the abundance of taxa between accessions were considered significant when adjusted P-values were lower than 0.1 at Phylum and Family level, and 0.05 at OTU level. Volcano plots were built to graphically represent the results of the moderated t-tests using the R package ggplot2 (v.2.0.0) (Wickham, 2009). To graphically represent the results obtained at Phylum and Family level, a script developed by Bulgarelli et al. (2015) was adapted, in which relative abundance of read counts per mil was used, as well as box plot representations using the R package ggplot2. Taxa above 5‰ relative abundance were plotted for Phylum and Family level analysis. Treemap (v.3.7.3) was used to visualize the significantly abundant OTU’s, the annotated taxonomy, the adjusted P-value and per mil relative abundance in bubble graphs, in which the size of the bubbles indicates the relative abundance per mil of the raw read counts.

Data access and bioinformatic analyses

The sequence data are deposited at the European Nucleotide Archive under accession number PRJEB19467. Data, scripts and codes used for statistical and bioinformatic analyses are available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.580027and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.556538, respectively.

Results and discussion

Genetic relatedness of common bean accessions

Diversity Array Technology analysis resulted in 7527 SNPs as genetic markers for the eight selected local common bean accessions. Phylogenetic and Bayesian clustering approaches as well as multidimensional scaling allowed us to decipher the divergence among the selected bean accessions (Figures 1b and c; Supplementary Figure S1). Bean accessions G22304 and G23998, originally selected for this study as wild and landrace, respectively, showed strong genetic concordance and were classified as wild or ‘Ancestral’ accessions A1 and A2, respectively (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). For the accession G51283K1, selected originally as a wild, a genome-wide comparison showed that it is more similar to the modern bean accessions than to the wild accessions (Supplementary Figure S2). We postulate that G51283K1 is probably a weedy accession, that is, the product of a cross between wild common bean and a modern cultivar (Toro et al., 1990). Hence, accession G51283K1 was classified together with G50398, G14947, G51695 and G5773, as ‘Modern’. Hereinafter, these five accessions are referred to as M1–M5, respectively (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Accession G50632I1, selected as a landrace, did not show significant similarity with any of the other bean accessions and was named L1 (Figures 1b and c; Supplementary Figure S3). Inference of the genetic diversity of the selected bean accessions further supported our classification: accessions M1–M5 have a higher number of homozygous segments and higher inbreeding coefficients than landrace L1 and wild accessions A1 and A2 (Figures 1d and e). Accessions A1 and A2 originate from the same geographic area where several wild relatives of common bean have been collected (Blair et al., 2012) (Figure 1a). The proximity between collection sites might partly explain the genotypic similarities between these two wild accessions.

Origin and genetic structure of the common bean accessions. (a) Map of Colombia depicting the geographic origin, accession number and classification of the bean accessions based on DArT genotyping performed in this study; (b) Neighbor joining and phylogenetic relatedness; (c) STRUCTURE analysis (k=3); (d) Number of homozygous segments; (e) Inbreeding coefficients (F-values). Green color is assigned to ancestral accessions A1 and A2, blue to the landrace accession L1 and red to modern accessions M1–M5. DArT, Diversity Array Technology.

Root phenotypic traits of wild and modern bean accessions

Wild accessions A1 and A2 had a similar specific root length (SRL: ratio of root length and dry weight) and a similar root density (ratio of dry weight and volume), different from the other bean accessions (Figure 2). These results confirm and extend earlier results found for wild common bean as compared to cultivars (Martín-Robles et al., 2015). Taken together, a high SRL and small diameter point to thinner roots and may provide a higher efficiency of water search and uptake, traits that are important for wild beans to prosper and survive in the dry native habitats (Toro et al. 1990, Comas et al., 2013). When harvested at flowering stage, significant differences were observed between the bean accessions in the number of days to reach flowering, the root dry weight and the number of nodules (ANOVA, P<0.005; Supplementary Figure S4). Consistent with previous findings (Toro et al. 1990), bean plants of the ancestral group require more days to reach flowering than the modern accessions. Only A2 presented a significant higher number of nodules per root system, while no significant differences were found between the other accessions (Supplementary Figure S4c).

Root morphology parameters of common bean accessions. (a) Specific Root Length is the product of root length divided by the root dry weight, and (b) Root density is the product of root dry weight divided by root volume. Root length and root volume were determined by WinRHIZO. Statistically significant differences between group means for SRL and for Root Density were determined by one-way ANOVA (P<0.05). Three replicates per accession were used. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (Fisher LSD test).

The common bean rhizobacterial diversity

As root exudation profiles may change due to specific root architectural features (Marschner et al., 2002), we hypothesized that the observed contrasting root morphologies and the genetic divergence between accessions may affect the rhizobacterial community composition. Plants were harvested at flowering to synchronize microbiome analyses for all bean accessions at the same phenological stage. Through sequencing of the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA, 2.4 million quality reads were recovered, identifying 12 293OTUs at 97% sequence similarity (Supplementary Table S4). For the α-diversity, we observed a significant reduction in the rhizosphere of all bean accessions as compared to the bulk soil (ANOVA, P<0.05) (Supplementary Figures S5 and S6). Between accessions, however, we did not find significant differences in the diversity indexes, except for the number of observed OTUs which was higher for M1 than for A1 (Tukey HSD, P<0.05). Bray–Curtis metrics and Constrained Analyses of Principal Coordinates further showed that the microhabitat (soil, rhizosphere) explained 30.2% of the β-diversity, that is, the total variability in bacterial community structure between groups (PERMANOVA, P<0.001). Accordingly, a significant separation between rhizosphere and bulk soil was observed (PERMANOVA P<0.005) (Figure 3a). This selective pressure of the rhizosphere on microbiome composition is well known (Lakshmanan et al., 2012; Badri et al., 2013) and most likely driven by the quantity and quality of root exudates in combination with different growth rates, substrate utilization spectra and competitive abilities of the rhizobacterial genera. The results further showed that 13.5% of the total variability in rhizobacterial community composition was explained by the bean genotype (PERMANOVA, P<0.001). The constrained analysis of the principal coordinates by phylogenetic group was significant (PERMANOVA, P<0.005) (Figure 3b). A Regularized Canonical Correlation Analysis further confirmed that the genetic make-up of the wild bean accessions correlates with their rhizobacterial community composition (Supplementary Figure S7). These results are in accordance with previous findings on maize and barley, where the impact of the plant genotype shapes host-dependent rhizosphere bacterial communities (Peiffer et al., 2013; Bulgarelli et al., 2015).

Rhizosphere bacterial community structure of common bean. Constrained Analysis of Principal Coordinates (CAP) of 16S rRNA diversity in the rhizosphere of the eight common bean accessions used in this study, with (a) and without (b) 16S rRNA diversity in the bulk soil, respectively. CSS transformed reads were used to calculate Bray–Curtis distances and a constrained analysis was performed by microhabitat (a) (30.2% of the overall variance; P<0.005) and bean group (b) (13.47% of the overall variance; P<0.005). Statistical significance of the constrained analysis was assessed by Permanova (P<0.005). CSS, cumulative-sum scaling.

Niche-based processes in rhizobacterial community assembly

The SAD models and the comparison of Akaike Information Criterion values showed that the rhizobacterial species abundance in the rhizosphere of all accessions and in the bulk soil are explained by niche-based distributions (Supplementary Figure S8 and Supplementary Table S5). In the case of the rhizosphere environment, root exudation is a strong modulating factor of rhizobacterial communities, where several taxa can thrive and become highly abundant while other community members exhibit low abundance (Jones et al., 2009). We also tested a neutral model in order to generate a SAD to be compared with the other niche-based models. With this model, a parameter (m) which accounts for the immigration rate into local communities from a regional pool is obtained (Etienne, 2005). Values closer to 1 indicate no dispersal limitation. The m values for bulk soil samples were closer to 1 as compared to those of the rhizosphere samples, suggesting a possible effect of neutral-driven processes in the bulk soil and at the same time a stronger niche-driven process in the rhizosphere of all the bean accessions tested (Supplementary Table S6).

Linking rhizobacterial community composition with the common bean genotype

To determine which rhizobacterial taxa were affected in a bean genotype-dependent manner, a Zero-Inflated Gaussian model was used to assess the differential abundance. At phylum level, all eight bean accessions presented an enrichment of Proteobacteria and a lower abundance of Acidobacteria as compared to the bulk soil (Supplementary Figures S9a). The phyla Bacteroidetes and Verrucomicrobia were significantly more abundant in the rhizosphere of the wild bean accessions, whereas the Actinobacteria were more abundant in the rhizosphere of the modern bean accessions (FDR<0.1; Figures 4a and b). At family level, a significant increase in the relative abundance of the Rhizobiaceae and Sphingomonadaceae was observed for all bean accessions as compared to the bulk soil (Supplementary Figures S9b). Following the bean genotypic trajectory from A1 through M5 (based on inbreeding coefficient and homozygosity), we observed a gradual decrease in the relative abundance of Chitinophagaceae and Cytophagaceae, both of the Bacteroidetes phylum (FDR<0.1; Figures 4c and d). Following this same trajectory, gradual increases in relative abundance were observed for the Nocardiodaceae (Actinobacteria) and Rhizobiaceae (Proteobacteria) (Figures 4g and h) and to some extent also for the Streptomycetae (Figure 4f). For Bacillaceae, however, no specific pattern in relative abundance was observed along the bean genotypic trajectory; this family was significantly more abundant only in the M5 rhizosphere (Figure 4e).

Relative abundance of bacterial phyla and families in the rhizosphere of the different bean accessions. The relative abundance (‰) of the phyla and families of four replicates per accession was used. At phylum level, results are shown for (a) Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria, and (b) Firmicutes and Verrucomicrobia. At family level, results are shown for representatives of the Bacteroidetes (Chitinophagaceae (c) and Cytophagaceae (d)). For the Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, results are shown for Bacillaceae (e), Streptomycetaceae (f) and Nocardioidaceae (g). For the phylum Proteobacteria, the relative abundance of the Rhizobiaceae (h) is shown. Different letters indicate significant differences between accessions (moderated t-test, FDR<0.1).

Next, we zoomed in on specific OTUs that were differentially enriched or depleted among the bean accessions by using the filtered OTU table. Based on the inbreeding coefficients and number of homozygous segments (Figures 1d and e), bean accessions A1 and M5 were the most divergent and therefore compared first to see if this divergence was also reflected in the rhizobacterial community composition. We found 221 OTUs enriched in the A1 rhizosphere and 181 OTUs enriched in the M5 rhizosphere (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S7). A1 was significantly enriched with representatives of the Chitinophagaceae family (25 OTUs). The genus Dyadobacter from the Cytophagaceae family was particularly enriched in the rhizosphere of A1. For the M5 rhizosphere, three out of the 10 most abundant OTUs were significantly enriched, belonging to Rhizobium (OTU9047), Streptomyces (OTU7) and Burkholderiales (OTU8). Also enriched in M5 were two highly abundant OTUs of the genus Arthrobacter (OTU17 and OTU886) and several OTUs from the family Nocardioidaceae (13 OTUs) and the genus Lysobacter (8 OTUs). All microbiome comparisons between A1 and the other bean accessions showed similar enrichments (Supplementary Figures S10–S14). Collectively, these analyses showed that OTUs from Bacteroidetes and Verrucomicrobia were enriched in the rhizosphere of accession A1, whereas OTUs from Actinobacteria were consistently enriched in the rhizosphere of accession M5. Similarly, when comparing A2 to M4 and to M5, we observed that OTUs from Chitinophagaceae family were consistently enriched in the A2 rhizosphere (Supplementary Figures S15 and S16). Also when we merged the data of the individual bean accessions into a collective data set for each of the two bean genotypic groups (that is, ancestral and modern), similar overall patterns and differences in rhizobacterial community composition were observed: Bacteroidetes (8 OTUs) and Verrucomicrobia (5 OTUs) were enriched in the ancestral group, whereas the phylum Actinobacteria (2 OTUs) was enriched in the modern group (Supplementary Figure S17).

Differential abundance of bacterial OTUs between the wild bean accession A1 and modern bean accession M5. The comparison was made using a zero-inflated Gaussian distribution mixture model followed by moderated t-test and a Bayesian approach. Data from four replicates per accession was used. Only OTUs significantly enriched in one of the two accessions are shown (FDR<0.05). The largest circles represents Phylum level. The inner circles represent Class and Family level. The color of the circles represents the OTUs enriched in the rhizosphere of wild accession A1 (green) or of modern accession M5 (red), with the assigned Genus in italics. The size of the circle is the mean read relative abundance of the differentially abundant OTU.

Intriguingly, Bacteroidetes have also been reported at higher relative abundance in the rhizosphere of other wild plant species and wild crop relatives, including Cardamine hirsuta (Schlaeppi et al., 2014), Beta vulgaris subsp. maritima (Zachow et al., 2014) and Hordeum vulgare subsp. spontaneum (Bulgarelli et al., 2015). In human microbiome research, Bacteroidetes have received considerable attention for their association with low carbohydrate diets, lean mice and weight loss in humans (Ley et al., 2006; Turnbaugh et al., 2006; De Filippo et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2012). Considering the increased abundance of Bacteroidetes on the thin roots of wild relatives of common bean and the higher relative abundance of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria on the thicker roots of modern varieties, it is tempting to make an analogy of ‘lean beans’ and ‘obese beans’. Whether the association with Bacteroidetes might result in a healthier development for plants as shown for animals, and whether its increased abundance on the roots of the wild relatives is a signature of coevolution remains speculative and opens exciting avenues for further research. More specifically, the putative link between the abundance of this bacterial Phylum in the rhizosphere of wild crop relatives and its ability to degrade complex biopolymers (Thomas et al., 2011) will be subject of future experiments. Also in terms of plant health, the Chitinophagaceae family, which belongs to the Bacteroidetes, has been proposed for their potential role in protection against soil-borne pathogens (Yin et al., 2013; Chapelle et al., 2016).

Linking rhizobacterial community composition with root phenotypic traits

Canonical Correspondence Analysis revealed that the overall variation in rhizobacterial community composition is explained for 11.4% (Bonferroni adjusted P=0.002) by the different root phenotypic traits (Figure 6a), which resembles the percentage of variation (13.5%) in rhizobacterial composition explained by the common bean genotype (Figure 3b). Among the root morphological and phenological traits included in the analysis, the SRL was responsible for most of the explained variation (Bonferroni adjusted P=0.008) followed by the number of nodules (Bonferroni adjusted P=0.016). The percentages of explanation for the variables Root Density and Root Dry Weight were not statistically significant. Interestingly, the dissimilarities between wild accessions A1 and A2 appears to be largely driven by the number of nodules. When the explanatory variables are used together with the bacterial phyla (Figure 6b) and bacterial families (Figure 6c), the results show that the abundance of Bacteroidetes families is explained by SRL, in contrast to the abundance of Actinobacterial families.

Constrained Canonical Correspondence Analysis of 16S sequence data and root morphological traits. (a) Root morphological traits as explanatory variables for the divergence between the overall rhizobacterial community composition of the eight different bean accessions. The rhizobacterial community composition is based on CSS normalized counts. Green triangles represent the replicates of the wild bean accessions A1 and A2, blue squares represent the landrace accession L1, and red circles represent the modern bean accessions M1–M5. The colored arrows represent the root morphological traits: Number of nodules and Dry root weight (black), Specific Root Length (SRL) and Root Density (red). (b) Same as in (a) depicting the root morphological traits as explanatory variables for the divergence between the different bacterial phyla. Only phyla with a relative abundance higher than 1% are colored: Acidobacteria (orange), Actinobacteria (red), Bacteroidetes (green), Firmicutes (blue), Proteobacteria (yellow) and Verrucomicrobia (light blue). (c) Same as in (b), depicting the root morphological traits as explanatory variables for the divergence between the bacterial families. Here, only the bacterial families belonging to Actinobacteria (red), Bacteroidetes (green), Verrucomicrobia (light blue) and Firmicutes (blue) were highlighted. CSS, cumulative-sum scaling.

Conclusions

In this study, we found significant associations between the rhizobacterial community composition, the common bean genotype and specific root phenotypic traits. The phyla Bacteroidetes and Verrucomicrobia were consistently more abundant in the rhizosphere of wild common bean accessions, whereas representatives of the phyla Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria were enriched on roots of modern bean accessions. What the impact of the observed shifts in microbiome composition is on growth and health of common bean will be subject of future studies, ultimately providing an answer to the larger question if plant domestication compromised (or not) the beneficial effects of the rhizosphere microbiome. The divergence in rhizobacterial community composition between wild and modern bean accessions suggest a plant genetic basis of rhizosphere microbiome assembly. While these concepts apply also to other important food crops (for example, cereals), only with legumes it is possible to study how nodulation, the rhizosphere microbiota and the relationships between these two types of plant–microbe interactions are intertwined. In our study, only wild bean accession A2 presented a higher number of nodules per root system, while no significant differences were found between the other bean accessions. This suggests that symbiotic nitrogen fixation per se may not be the major driver of the root microbiome composition as was elegantly shown recently for Lotus japonicum (Zgadzaj et al., 2016). These results also imply that other or additional host-derived cues shape the bean rhizosphere microbiota. The relatively small sample size used in our study precludes a statistically robust GWAS analysis but did provide a well differentiated set of traits in wild and modern accessions associated with a number of bacterial taxa. In-depth genetic and phenotypic analyses of a larger population of plant accessions (Kraft et al., 2009) will be needed for the identification of genes or molecular markers that ultimately can be used in plant breeding programs for the recruitment of specific plant-beneficial microbial taxa.

References

Akibode S, Maredia M . (2011) Global and regional trends in production, trade and consumption of food legume crops. Report submitted to the CGIAR Standing Panel on Impact Assessment http://www.cgiar.org/our-research/crop-factsheets/beans/).

Badri DV, Chaparro JM, Zhang R, Shen Q, Vivanco JM . (2013). Application of natural blends of phytochemicals derived from the root exudates of Arabidopsis to the soil reveal that phenolic related compounds predominantly modulate the soil microbiome. J Biol Chem 288: 4502–4512.

Berg G, Smalla K . (2009). Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 68: 1–13.

Bitocchi E, Nanni L, Bellucci E, Rossi M, Giardini A, Zeuli PS et al. (2012). Mesoamerican origin of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) is revealed by sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: E788–E796.

Blair MW, Soler A, Cortés AJ . (2012). Diversification and population structure in common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). PLoS One 7: e49488.

Broughton WJ, Hernández G, Blair M, Beebe S, Gepts P, Vanderleyden J . (2003). Beans (Phaseolus spp.)—model food legumes. Plant Soil 252: 55–128.

Brown K, DeCoffe D, Molcan E, Gibson DL . (2012). Diet-induced dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and the effects on immunity and disease. Nutrients 4: 1095–1119.

Bulgarelli D, Garrido-Oter R, Münch PC, Weiman A, Dröge J, Pan Y et al. (2015). Structure and function of the bacterial root microbiota in wild and domesticated barley. Cell Host Microbe 17: 392–403.

Bulgarelli D, Rott M, Schlaeppi K, van Themaat EVL, Ahmadinejad N, Assenza F et al. (2012). Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature 488: 91–95.

Bulgarelli D, Schlaeppi K, Spaepen S, van Themaat EVL, Schulze-Lefert P . (2013). Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 64: 807–838.

Carvalhais LC, Dennis PG, Badri DV, Tyson GW, Vivanco JM, Schenk PM . (2013). Activation of the jasmonic acid plant defence pathway alters the composition of rhizosphere bacterial communities. PLoS One 8: e56457.

Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LCAM, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ . (2015). Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience 4: 7.

Chapelle E, Mendes R, Bakker PAHM, Raaijmakers JM . (2016). Fungal invasion of the rhizosphere microbiome. ISME J 10: 265–268.

Cole JR, Wang Q, Fish JA, Chai B, McGarrell DM, Sun Y et al. (2014). Ribosomal Database Project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D633–D642.

Comas LH, Becker SR, Cruz VMV, Byrne PF, Dierig DA . (2013). Root traits contributing to plant productivity under drought. Front Plant Sci 4: 442.

De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S et al. (2010). Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 14691–14696.

Desiderio F, Bitocchi E, Bellucci E, Rau D, Rodriguez M, Attene G et al. (2013). Chloroplast microsatellite diversity in Phaseolus vulgaris. Front Plant Sci 3: 1–15.

Dodt M, Roehr JT, Ahmed R, Dieterich C . (2012). FLEXBAR—flexible barcode and adapter processing for next-generation sequencing platforms. Biology 1: 895–905.

Doebley JF, Gaut BS, Smith BD . (2006). The molecular genetics of crop domestication. Cell 127: 1309–1321.

Dumbrell AJ, Nelson M, Helgason T, Dytham C, Fitter AH . (2010). Relative roles of niche and neutral process in structuring a soil microbial community. ISME J 4: 337–345.

Earl DA . (2012). STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour 4: 359–361.

Edgar RC . (2010). Search and clustering hundreds of times faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26: 2460–2461.

Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R . (2011). UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27: 2194–2200.

Etienne RS . (2005). A new sampling formula for neutral biodiversity. Ecol Lett 8: 253–260.

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J . (2005). Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol 14: 2611–2620.

Gepts P . (1998). Origin and evolution of common bean: past events and recent trends. HortScience 33: 1124–1130.

Gepts P, Bliss FA . (1985). F1 hybrid weakness in the common bean. J Hered 76: 447–450.

Gepts P, Bliss FA . (1986). Phaseolin variability among wild and cultivated common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris from Colombia. Econ Bot 40: 469–478.

González I, Déjean S . (2012). CCA: Canonical correlation analysis. R package version 1.2 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=CCA.

Gotelli NJ, Colwell RK . (2001). Quantifying biodiversity: procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol Lett 4: 379–391.

Illumina.. (2013). 16S Metagenomic sequencing library preparation http://support.illumina.com/downloads/16s_metagenomic_sequencing_library_preparation.html.

Jabot F, Etienne RF, Chave J . (2008). Reconciling neutral community models and environmental filtering: theory and an empirical test. Oikos 117: 1308–1320.

Jaccoud D, Peng K, Feinstein D, Kilian A . (2001). Diversity arrays: a solid state technology for sequence information independent genotyping. Nucleic Acids Res 29: e25.

Jones DL, Nguyen C, Finlay RD . (2009). Carbon flow in the rhizosphere: carbon trading at the soil–root interface. Plant Soil 321: 5–33.

Köster J, Rahmann S . (2012). Snakemake-a scalable bioinformatics workflow engine. Bioinformatics 28: 2520–2522.

Kraft P, Zeggini E, Ioannidis JPA . (2009). Replication in genome-wide association studies. Stat Sci 24: 561–573.

Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Walters WA, González A, Caporaso JG, Knight R . (2012). Using QIIME to analyze 16S rRNA gene sequences from microbial communities. Curr Protoc Chem Biol 1E: 1–20.

Lakshmanan V, Kitto SL, Caplan JL, Hsueh YH, Kearns DB, Wu YS et al. (2012). Microbe-associated molecular patterns-triggered root responses mediate beneficial rhizobacterial recruitment in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 160: 1642–1661.

Lebeis SL, Paredes SH, Lundberg DS, Breakfield N, Gehring J, McDonald M et al. (2015). Salicylic acid modulates colonization of the root microbiome by specific bacterial taxa. Science 349: 860–864.

Leff JW, Lynch RC, Kane NC, Fierer N . (2016). Plant domestication and the assembly of bacterial and fungal communities associated with strains of the common sunflower, Helianthus annuus. New Phytol 214: 412–423.

Ley RE, Peterson DA, Gordon JI . (2006). Ecological and evolutionary forces shaping microbial diversity in the human intestine. Cell 124: 837–848.

Lundberg DS, Lebeis SL, Paredes SH, Yourstone S, Gehring J, Malfatti S et al. (2012). Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome. Nature 488: 86–90.

Marschner P, Neumann G, Kania A, Weiskopf L, Lieberei R . (2002). Spatial and temporal dynamics of the microbial community structure in the rhizosphere of cluster roots of white lupin (Lupinus albus L.). Plant Soil 246: 167–164.

Martín-Robles N, Morente-López J, Milla R . (2015). Digging up the roots of crop evolution. Libro de resúmenes de comunicaciones del 4° Congreso Ibérico de Ecología, Coimbra, Portugal doi:10.7818/4IberianEcologicalCongress.2015.

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S . (2013). phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8: e61217.

McDonald D, Clemente JC, Kuczynski J, Rideout JR, Stombaugh J, Wendel D et al. (2012). The Biological Observation Matrix (BIOM) format or: how I learned to stop worrying and love the ome-ome. Gigascience 1: 7.

Masella AP, Bartram AK, Truszkowski JM, Brown DG, Neufeld JD . (2012). PANDAseq: paired-end assembler for illumina sequences. BMC Bioinform 13: 31.

Mendes LW, Kuramae EE, Navarrete AA, van Veen JA, Tsai SM . (2014). Taxonomical and functional microbial community selection in soybean rhizosphere. ISME J 8: 1577–1587.

Mendes R, Garbeva P, Raaijmakers JM . (2013). The rhizosphere microbiome: significance of plant beneficial, plant pathogenic, and human pathogenic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev 37: 634–663.

Mendes R, Kruijt M, de Bruijn I, Dekkers E, van der Voort M, Schneider JHM et al. (2011). Deciphering the rhizosphere microbiome for disease-suppressive bacteria. Science 332: 1097–1100.

Ofek M, Voronov-Goldman M, Hadar Y, Minz D . (2014). Host signature effect on plant root-associated microbiomes revealed through analyses of resident vs. active communities. Environ Microbiol 16: 2157–2167.

Oksanen J, Kindt R, Legendre P, O’Hara B, Simpson GL, Solymos P et al. (2016). vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.4-0 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

Paulson JN, Stine OC, Bravo HC, Pop M . (2013). Differential abundance analysis for microbial marker-gene surveys. Nat Methods 10: 1200–1202.

Paulson JN, Talukder H, Pop M, Bravo HC . (2016). metagenomeSeq: Statistical analysis for sparse high-throughput sequencing. Bioconductor package: 1.12.0 http://cbcb.umd.edu/software/metagenomeSeq.

Peiffer JA, Spor A, Koren O, Jin Z, Tringe SG, Dangl JL et al. (2013). Diversity and heritability of the maize rhizosphere microbiome under field conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 6548–6553.

Pérez-Jaramillo JE, Mendes R, Raaijmakers JM . (2016). Impact of plant domestication on rhizosphere microbiome assembly and functions. Plant Mol Biol 90: 635–644.

Philippot L, Raaijmakers JM, Lemanceau P, van der Putten WH . (2013). Going back to the roots: the microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nature Rev Microbiol 11: 789–799.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P . (2000). Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155: 945–959.

R Core Team.. (2015). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria https://www.R-project.org/.

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W et al. (2015). limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43: e47.

Rognes T, Mahé F, Flouris T, Quince C, Nichols B . (2015). VSEARCH version 1.0.16 https://github.com/torognes/vsearch.

Schlaeppi K, Dombrowski N, Oter RG, van Themaat EVL, Schulze-Lefert P . (2014). Quantitative divergence of the bacterial root microbiota in Arabidopsis thaliana relatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 585–592.

Thomas F, Hehemann JH, Rebuffet E, Czjzek M, Michel G . (2011). Environmental and gut bacteroidetes: the food connection. Front Microbiol 2: 93.

Toro O, Tohme J, Debouck D . (1990). Wild bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): description and distribution (International Board for Plant Genetics Resources (IBGPR) and Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT), Cali, Colombia).

Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI . (2006). An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444: 1027–1031.

Turner TR, Ramakrishnan K, Walshaw J, Heavens D, Alston M, Swarbreck D et al. (2013). Comparative metatranscriptomics reveals kingdom level changes in the rhizosphere microbiome of plants. ISME J 7: 2248–2258.

Wickham H . (2009) ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag: New York.

Yin C, Hulbert SH, Schroeder KL, Mavrodi O, Mavrodi D, Dhingra A et al. (2013). Role of bacterial communities in the natural suppression of Rhizoctonia solani Bare Patch Disease of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Appl Environ Microbiol 79: 7428–7438.

Zachow C, Müller H, Tilcher R, Berg G . (2014). Differences between the rhizosphere microbiome of Beta vulgaris ssp. maritima - ancestor of all beet crops - and modern sugar beets. Front Microbiol 5: 415.

Zgadzaj R, Garrido-Oter R, Jensen DB, Koprivova A, Schulze-Lefert P, Radutoiu S . (2016). Root nodule symbiosis in Lotus japonicus drives the establishment of distinctive rhizosphere, root, and nodule bacterial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: E7996–E8005.

Acknowledgements

JEP-J was financially supported by the Department of Science, Technology and Innovation of Colombia—COLCIENCIAS through the doctoral grant 568-2012-15517825. JMR and VJC were supported by the Dutch STW-program ‘Back to the Roots’ and RM by CNPq 443112/2014-2. We are grateful for the expert help from Dr O Toro (RIP), Dr D DeBouck and LG Santos at the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT, Cali, Colombia) in the selection of the bean accessions. We are also grateful to HA Pérez and JA Osorio for collecting the soil for the greenhouse experiments. We thank G Bongiorno and NM Robles for their valuable help in root phenotyping and JN Paulson for his expert advice in using the R package metagenomeSeq., this is publication 6290 of the NIOO-KNAW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez-Jaramillo, J., Carrión, V., Bosse, M. et al. Linking rhizosphere microbiome composition of wild and domesticated Phaseolus vulgaris to genotypic and root phenotypic traits. ISME J 11, 2244–2257 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.85

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.85

This article is cited by

-

Exploration of genes encoding KEGG pathway enzymes in rhizospheric microbiome of the wild plant Abutilon fruticosum

AMB Express (2024)

-

Influence of scion cultivar on the rhizosphere microbiome and root exudates of Phaseolus vulgaris in grafting system

Plant and Soil (2024)

-

Intra- and inter-annual changes in root endospheric microbial communities of grapevine are mainly deterministic

Plant and Soil (2024)

-

Effect of rootstock diversity and grafted varieties on the structure and composition of the grapevine root mycobiome

Plant and Soil (2024)

-

A symbiotic footprint in the plant root microbiome

Environmental Microbiome (2023)