Africa’s outbreak sentinels

How monitoring wildlife can prevent the next pandemic

In mid-December 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially certified the end of the Ebola outbreak that had affected residents of the Beni Health Zone in North Kivu Province, Democratic Republic of Congo. The declaration was made in accordance with WHO recommendations, 42 days after the second negative test of the last confirmed case.

The WHO reported a total of eleven cases (eight confirmed and three probable), of whom only two survived. Of the nine deaths, seven were in the community and two occurred at the Ebola Treatment Centre.

Vaccination and prompt public health responses had crucial roles in ensuring that this outbreak saw fewer cases than did previous Ebola outbreaks. But despite a lower case count, some researchers are frustrated at a perceived inability to take the required actions needed to stop the spread of zoonotic diseases, such as those caused by the related Ebola and Marburg viruses. These filoviruses have their reservoir in bats and will continue to pose a risk to the region unless a preventative, One Health approach is taken, say the researchers.

With the world more highly connected than ever before, a health threat in the Congolese jungle could quickly pose a major threat to global health. Any emerging infection is not just a local phenomenon but is of potential global importance.

Deforestation drives disease

Parrot’s Beak is a curved strip of land in Guinea, between the Meli River and Mokona River, that juts into Sierra Leone, just north of the country’s border with Liberia.

Parrot’s Beak is home to colonies of fruit bats that harbor Marburg virus, a relative of Ebola virus. Humans come in close proximity to the bats, which results in humans catching the virus and then transmitting Marburg to others via bodily fluids.

Fruit bats live in forests, but these are shrinking. More than 20 years before Guinea recorded the region’s first case of Marburg, the United Nations Environment Programme warned that the unique forests of the region had dramatically diminished over the past few decades, as civil war in Sierra Leone and Liberia pushed thousands of refugees into Parrot’s Beak.

Parrot’s Beak was covered with deep green forests in 1974, but civil wars pushed refugees into the area.

By 1999, much of the forest had been cut down for housing, charcoal and agriculture.

“People have cut down the forests for housing materials, wood for charcoal, and space to grow crops. Some commercial logging also played a role,” a NASA report notes.

The United Nations Environment Programme has attributed the disruption of the Parrot’s Beak ecosystem to newcomers creating their own family plots, which merged with existing areas of deforestation.

With the population of Parrot’s Beak continuing to grow, residents have become increasingly dependent on the environment for their livelihoods, such as farming. Increasing use of agriculture increases deforestation, which puts residents in closer proximity to wildlife, including bats, which in turn increases the risk of zoonotic diseases such as Ebola and Marburg.

Forests are cleared for agriculture, which increases the risk of zoonotic diseases. Credit: Evan Bowen-Jones / Alamy Stock Photo.

Forests are cleared for agriculture, which increases the risk of zoonotic diseases. Credit: Evan Bowen-Jones / Alamy Stock Photo.

A One Health approach

There is already an approach to the nexus of environmental, animal and human health: One Health. The WHO describes One Health as designing and implementing programs, policies, legislation and research in which multiple sectors communicate and work together to achieve better public health outcomes.

“The areas of work in which a One Health approach is particularly relevant include food safety, the control of zoonoses, and combating antibiotic resistance,” says the WHO in a Q&A on the topic.

Disrupting the interactions between the environment, animals and humans that increase the risk of emerging infectious diseases could have far-reaching effects. But actions to achieve a One Health approach, such as wildlife surveillance, are prioritized below vaccination, which some public health officials argue is a short-term approach. A One Health approach is especially important in countries such as Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, which border Parrot’s Beak, and where the WHO is concerned about the risk of emerging and re-emerging diseases.

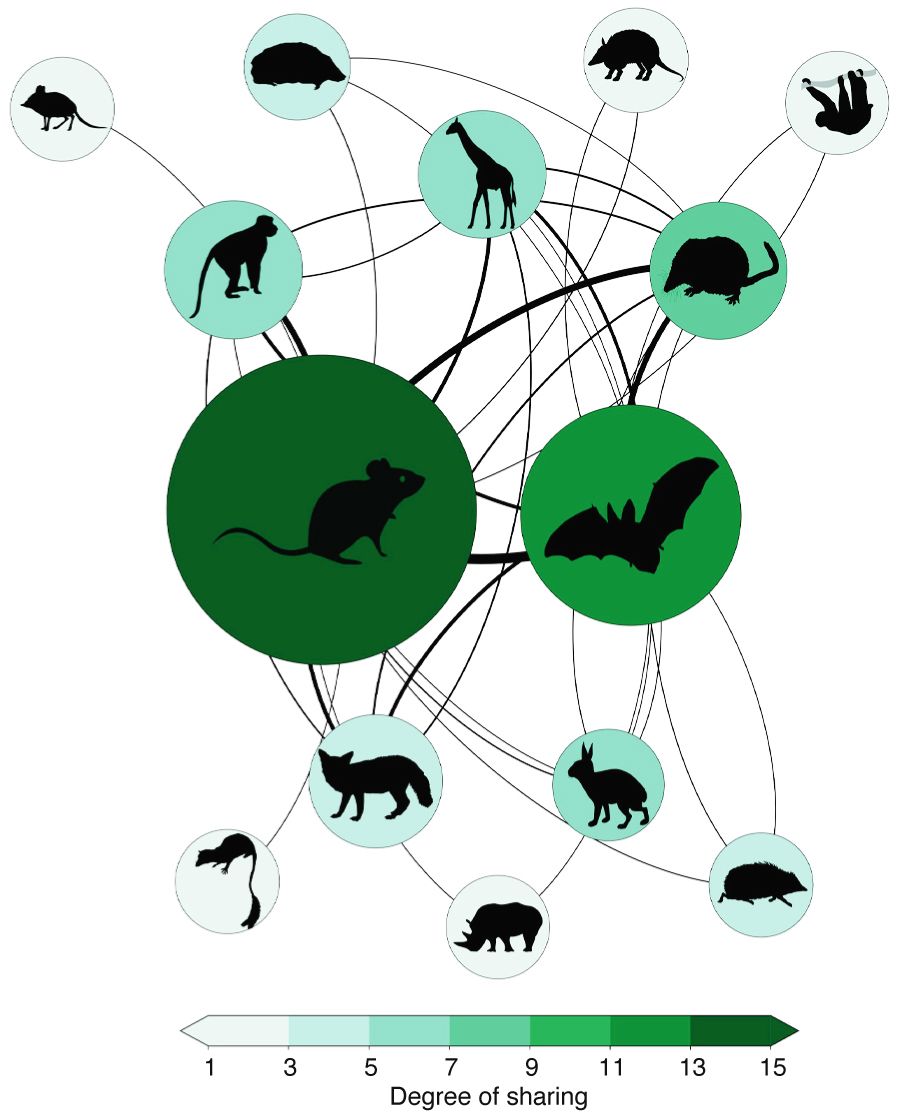

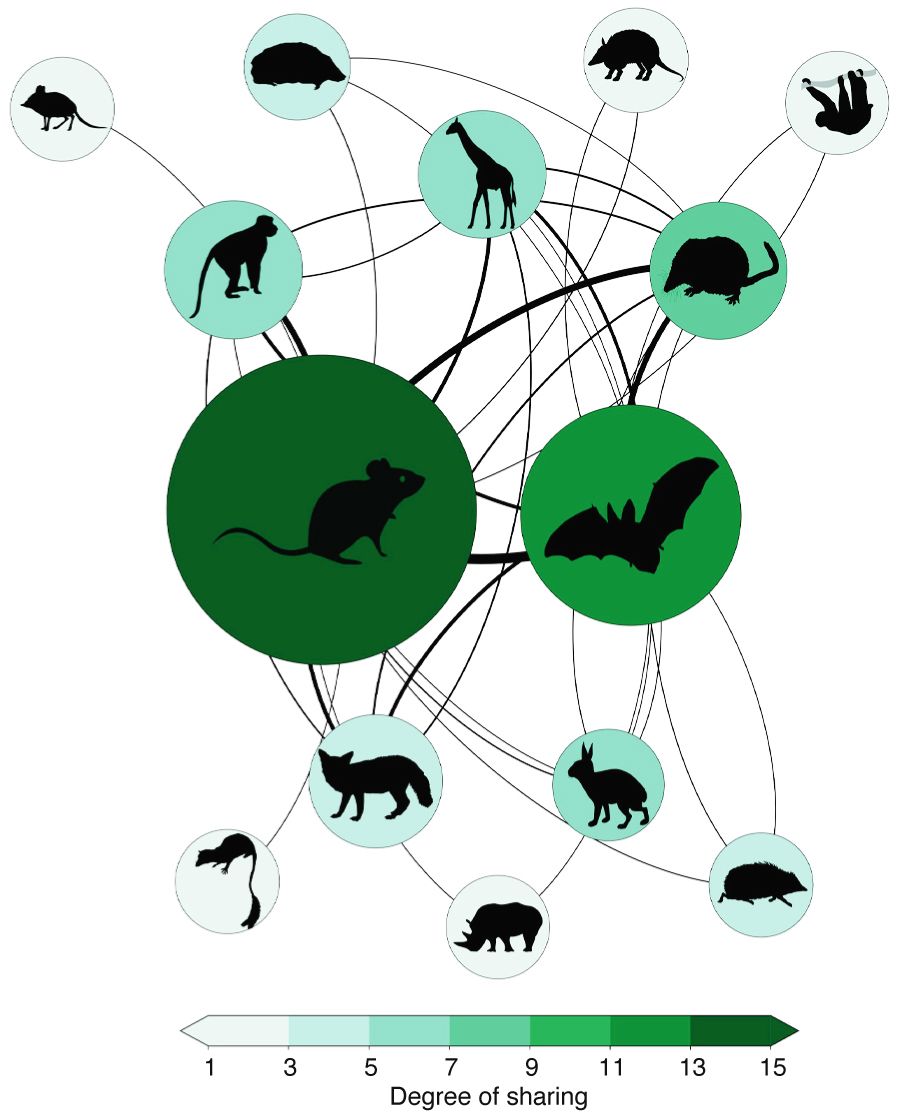

Viruses are shared between various mammal species, especially rodents and bats. Intensity of shading indicates the degree of sharing (key). Image: Carlson, C.J. et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w (2022).

In August 2021, when a suspected case of Ebola was identified in Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast), the person was found to have traveled there by road from Guinea. Pierre Dimba, Minister of Health of Cote d’Ivoire, told Nature Medicine that the top priority was quickly rolling out the vaccine against Ebola via a ring-vaccination method. According to Dimba, the One Health approach needs to be better researched before full implementation is feasible.

“One Health is very relevant because we're fighting different outbreaks at the same time. The interaction between wild animals and human beings gives rise to diseases like Ebola and Marburg. We have adopted a consultation approach and will review the report. We [however] need to accelerate research. We should have research at the local level to [be able to] anticipate this type of problem, and be able to react,” Dimba tells Nature Medicine.

Viruses are shared between various mammal species, especially rodents and bats. Intensity of shading indicates the degree of sharing (key). Image: Carlson, C.J. et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w (2022).

Viruses are shared between various mammal species, especially rodents and bats. Intensity of shading indicates the degree of sharing (key). Image: Carlson, C.J. et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w (2022).

One Health timeline

1821–1902: Rudolf Virchow coins the term ‘zoonosis’ to describe an infectious disease that passes from animals to humans.

1964: Calvin Schwabe, a veterinary epidemiologist at University of California Davis, coins the term ‘One Medicine’ to describe similarities between human and veterinary medicine.

1976: First outbreak of Ebola virus in the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire).

2004: The Manhattan Principles call for an international, interdisciplinary approach to prevent disease, which formed the basis for the One Health, One World concept.

2014: First outbreak of Ebola virus in west Africa, with 28,610 cases in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.

2015: Outbreaks of H5N1 highly pathogenic influenza virus in poultry across west Africa.

2016: First epidemic of Rift Valley fever virus in humans and animals in Niger.

2021: Endorsement of an Animal Health Strategy for Africa.

Credit: S. Fenwick/Springer Nature Limited.

Behavior changes

In November 2019, the WHO paved the way, for the first time, for the use of a vaccine against Ebola in high-risk countries with the pre-qualification of rVSV-ZEBOV (Ervebo/Merck). The vaccine, based on a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus that expresses the Ebola virus glycoprotein, is now a core pillar of Ebola preparedness and response in Africa.

Muhammed Afolabi, a researcher at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, co-authored a study that proposed the rollout of vaccination against Ebola in Africa. Afolabi notes that although routine use of the vaccine against Ebola will improve compliance and ensure that people receive both doses, use of vaccines is more straightforward than attempting to disrupt disease transmission via the One Health approach.

Outbreaks are caused by human activities such as wildlife trapping.

“We’ve heard the story of how an Ebola outbreak once started with a child innocently playing with droppings from bats. He got sick and soon infected his entire family. That was how it quickly spread within the community and across countries — spreading from Guinea to Sierra Leone and from Sierra Leone to Liberia,” says Afolabi.

Because human behaviors are difficult to change, many activities that bring humans in the region in contact with wildlife reservoirs of diseases cannot be stopped easily, notes Afolabi.

Viruses can jump from animals to humans through the eating of bushmeat.

“If you tell people don’t eat bats, they can argue that it is a delicacy they have been enjoying for ages. They will still do it. This is why vaccines will continue to be relevant in protecting people when they come in contact with the virus as a result of their activities and behaviors,” Afolabi tells Nature Medicine.

Daniela Manno, who has written on vaccines with Afolabi and is also at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, argues that vaccination and One Health do not have to be mutually exclusive, and that countries in Africa can pursue both.

Deforestation destroys animal habitats.

“The Ebola vaccine gives us a powerful tool to prevent outbreaks as prophylaxis in areas that are at risk of Ebola outbreaks. But we also need to look at why Ebola is coming back and the interactions between wildlife and human behavior. We probably have more things to understand about this virus. For me, the two things are actually working together in a way,” Manno tells Nature Medicine.

Images from Otu et al. Nat. Med. 27, 943–946 (2021).

Credit: Clement Meseko and Daniel Otokpa.

Outbreaks are caused by human activities such as wildlife trapping.

Outbreaks are caused by human activities such as wildlife trapping.

Viruses can jump from animals to humans through the eating of bushmeat.

Viruses can jump from animals to humans through the eating of bushmeat.

Deforestation destroys animal habitats.

Deforestation destroys animal habitats.

A nascent approach

On 1 November 2021, just before US President Joe Biden and other world leaders delivered their remarks at the COP26 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Scotland, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) held the opening ceremony for its inaugural One Health Conference.

Nick Nwankpa, director of the Pan African Veterinary Vaccine Center of African Union, remarked that zoonotic diseases have high socioeconomic effects in Africa, with endemic zoonoses such as Lassa fever and Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever heavily affecting low-income populations in both urban areas and rural areas.

“The challenge we face today is that most of the health systems in Africa are not adequately prepared to prevent and control both endemic and emerging zoonoses,” said Nwankpa at the meeting.

One Health approaches are still at an early stage in Africa. For example, the Animal Health Strategy for Africa, which provides guidance for One Health stakeholders, was endorsed by the continent's Heads of State and Government only as recently as 2021.

Yewande Alimi leads One Health activities for Africa CDC, the African Union and Member States and says that work on One Health officially commenced in February 2019, when a group of experts at Africa CDC, together with technical experts, developed a framework for One Health practices in Africa's national public health institutes.

Rwanda leads the way

Although the continent-wide strategy on One Health is still in its early stages, some countries are much further ahead. Rwanda stands out as a One Health pioneer, having started its One Health strategic plan in 2011, and has had an Infectious Disease Surveillance Response system since 1998.

Students at Rwanda’s University of Global Health Equity, which has pioneered One Health approaches. Credit: 64 Waves for UGHE.

Students at Rwanda’s University of Global Health Equity, which has pioneered One Health approaches. Credit: 64 Waves for UGHE.

At the Butaro-based University of Global Health Equity in Rwanda, Gloria Igihozo worked at the Center for One Health before moving to the Institute of Global Health. Rwanda has clear plans and policies for zoonotic infections, has integrated One Health approaches into university curricula in order to develop a One Health workforce, has developed multidisciplinary rapid response teams, and has created decentralized laboratories in the animal and human health sectors to strengthen surveillance.

“Rwanda’s integration of One Health into its response systems to infectious diseases and to COVID-19 demonstrates the importance of applying One Health principles into the governance of infectious diseases at all levels. Rwanda exemplifies how preparedness and response to outbreaks and pandemics can be strengthened through multisectoral collaboration mechanisms,” Igihozo’s team stated in a recent article.

In addition to their presence in Rwanda, One Health networks and initiatives are spatiotemporally spreading across Sub-Saharan Africa. But a study from Folorunso Fasina and colleagues from the Food and Agriculture Organization in Tanzania reports that these networks have skill gaps, especially in policy, budgeting, geography and environment.

Rwanda leads the way

Although the continent-wide strategy on One Health is still in its early stages, some countries are much further ahead. Rwanda stands out as a One Health pioneer, having started its One Health strategic plan in 2011, and has had an Infectious Disease Surveillance Response system since 1998.

At the Butaro-based University of Global Health Equity in Rwanda, Gloria Igihozo worked at the Center for One Health before moving to the Institute of Global Health. Rwanda has clear plans and policies for zoonotic infections, has integrated One Health approaches into university curricula in order to develop a One Health workforce, has developed multidisciplinary rapid response teams, and has created decentralized laboratories in the animal and human health sectors to strengthen surveillance.

“Rwanda’s integration of One Health into its response systems to infectious diseases and to COVID-19 demonstrates the importance of applying One Health principles into the governance of infectious diseases at all levels. Rwanda exemplifies how preparedness and response to outbreaks and pandemics can be strengthened through multisectoral collaboration mechanisms,” Igihozo’s team stated in a recent article.

In addition to their presence in Rwanda, One Health networks and initiatives are spatiotemporally spreading across Sub-Saharan Africa. But a study from Folorunso Fasina and colleagues from the Food and Agriculture Organization in Tanzania reports that these networks have skill gaps, especially in policy, budgeting, geography and environment.

Image: Students at Rwanda’s University of Global Health Equity, which has pioneered One Health approaches. Credit: 64 Waves for UGHE.

Risks from climate change

One source of potential funding for One Health approaches that tackle emerging infections could come from climate change grants. Climate change will increase the risk of zoonotic infections, according to a study recently published in Nature. Africa is the continent with the smallest contribution to greenhouse gas emissions but may be the worst hit by climate change. This uniquely positions the continent to receive funding for climate change adaptation and loss and damage from the world’s top emitters and richer countries, says Al-Hamndou Dorsouma, the African Development Bank’s officer in charge of climate change and green growth.

Hundreds of novel virus-sharing events among mammal species are projected to occur by 2070, mainly in Africa and Southeast Asia. Image: Carlson, C.J., et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w (2022).

Hundreds of novel virus-sharing events among mammal species are projected to occur by 2070, mainly in Africa and Southeast Asia. Image: Carlson, C.J., et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w (2022).

The WHO is working with African countries to position One Health approaches as part of climate adaptation, says Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa.

“We’ve also created a strong partnership with the United Nations Environment Programme, enabling countries themselves to establish mechanisms [whereby] health will be included, because we know that the results of climate change on health can be quite profound. And we are very interested in our countries benefiting from some of the financing for climate change and adaptation, so that some of the vector-borne infectious diseases can be prevented,” says Moeti.

Moeti admits that more needs to be done to integrate One Health approaches with policy on the environment and climate change.

Cooperation between countries

The disruption of human–wildlife interactions heightens the risk of emerging and re-emerging zoonotic diseases. Georges Ki-Zerbo, the WHO’s representative in Guinea, tells Nature Medicine that current measures are geared toward improving the surveillance of emerging infections so that cases can be quickly identified in communities and patients can be quickly isolated, in order to prevent major outbreaks.

“It is this improved surveillance that has helped us to identify cases of disease; it is also going to help us to quickly detect future cases,” says Ki-Zerbo.

Countries recognize that they need to work together, says Ki-Zerbo, as an outbreak of an emerging infection detected in one country could just as easily have been detected in another. Similarly, a single infected person in one location can easily and quickly travel across the region if countries do not integrate their plans and implement their response efforts.

“We cannot say we will no longer have such [outbreaks]. What is more important is our level of preparedness. We are making sure that we improve on testing and response,” he adds.

John Nkengasong, outgoing director of Africa CDC, has been arguing for a new public health order since before the COVID-19 pandemic. This would prioritize holistic preventive actions to tackle emerging infections while also boosting and improving responses.

Such an approach is needed to tackle any disease — whether it is COVID-19 or Ebola, says the Cameroonian virologist.

“We [Africa CDC] have been very clear that as a continent, we surely need a new public health order, and we have said this before the [COVID-19] pandemic and we are very insistent on this,” says Nkengasong.

He notes that strengthening Africa’s public health institutions and fostering regional collaborations are critical for achieving One Health goals and are essential for preventing and quickly responding to disease outbreaks.

“We believe strongly that there's a lot of power in regionalism. A lot of evidence is there to show what we've been able to achieve by coordinating within the African continent. And if you coordinate that more effectively, then it fits into the overall global architecture. I think we should really take this to heart,” Nkengasong adds.

Ki-Zerbo points to the importance of risk communication, in which residents are shown the daily activities that put them at risk of disease. This approach can be used to introduce a One Health approach to local communities while also helping them to stay safe.

“We need to be strategic in improving our risk communication that currently includes awareness on infection prevention and control measures, but we should also ensure that fatigue does not set in if we are directing different intervention efforts to the people,” says Ki-Zerbo.

In the end, the success of the One Health approach will not be with a bang, but with the lack of an outbreak. Another pandemic is inevitable, but One Health approaches, if more widely implemented, should make them less common.

Author information

Paul Adepoju

Freelance writer

Lagos, Nigeria

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Correction 17 June 2022: This article had incorrect details for the University of Global Health Equity in Rwanda and has been updated.