Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine the surgical outcome of posterior layer advancement of the lower eyelid retractors (LER) with transcanthal canthopexy for involutional lower eyelid entropion.

Patients and methods

Fifty-one eyelids of 41 patients with involutional entropion and vertical and horizontal laxities that underwent posterior layer advancement of the LER with transcanthal canthopexy were retrospectively reviewed. As a control, we also reviewed previously reported data from 47 entropic eyelids of 37 patients with vertical and horizontal laxities that were successfully corrected using LER advancement and a lateral tarsal strip procedure. Surgical success was defined as the normal eyelid position without contact of any cilia to the globe at the last follow-up examination.

Results

All eyelids in the present study group were judged as successfully treated without recurrence after 13.9±9.2 months of follow up (mean±SD). The surgical time in the present study group (22.4±5.5 min) was significantly shorter than that in the control group (mean 31.3±4.9 min; P<0.001; Student’s t-test). None of the patients showed lateral canthal deformity after surgery.

Conclusions

Posterior layer advancement of the LER with transcanthal canthopexy provided complete surgical success with shorter surgical time without the risk of lateral canthal deformity. Posterior layer advancement of the LER with transcanthal canthopexy can be an option for correction of involutional lower eyelid entropion in patients with both vertical and horizontal laxities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recurrence is the most serious complication in involutional lower eyelid entropion repair. To reduce the risk of recurrence, surgeons need to address two main pathophysiological mechanisms of this entity: vertical and horizontal laxities.1, 2, 3 The vertical laxity is caused by looseness of the lower eyelid retractors (LER), and the horizontal laxity is mainly induced by the less tense canthal-supporting structures.3

We previously reported complete surgical success after a combination surgery of the posterior layer advancement of the LER (ie, LER advancement) with a lateral tarsal strip (LTS) procedure in 47 eyelids with vertical and horizontal laxities.1 The LER advancement is based on the double-layer anatomy of the LER, of which the posterior layer is the main vertical traction component of the lower eyelid.4, 5 A definite advancement and fixation of the posterior layer can securely correct the vertical laxity.1 The LTS tightens the lower eyelid horizontally at the lateral canthus.6 Although this combination surgery achieved a favourable result, the surgical time was long and the LTS occasionally caused a post-operative lateral canthal deformity.7

To address the above two drawbacks of our previous procedure,1 we used the transcanthal canthopexy instead of the LTS for correction of the horizontal laxity. The transcanthal canthopexy is an eyelid-tightening procedure at the lateral canthus with a suture without the risk of a post-operative lateral canthal deformity.8 The horizontal tension is generally weakened, however, after a certain postoperative period.7

We examined surgical outcomes of the LER advancement with transcanthal canthopexy for involutional entropion in patients with both vertical and horizontal laxities.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective chart review of all patients who underwent the LER advancement with transcanthal canthopexy for involutional entropion by two oculoplastic surgeons (YT and HK) between September 2012 and August 2015. Fifty-one eyelids (right, 23 eyelids; left, 28 eyelids) of 41 patients (average age, 76.4±8.3 years; range, 59–97 years) were included in this study (Group A). Two eyelids of two patients had a history of prior entropion surgery at another clinic (LER application in one patient and unknown in one patient). Information was collected from each patient’s medical records, including patient age, gender, follow-up periods, preoperative evaluation of the vertical and horizontal eyelid laxities, surgical time, surgical success, and complications, including lateral canthal deformity. To form a control group, we reviewed previously reported data from 47 entropic eyelids of 37 patients with vertical and horizontal laxities, which were successfully corrected using LER advancement with a LTS by the same oculoplastic surgeons between July 2005 and May 2013 (Group B).1 All patients in both groups were followed up for more than 6 months.

Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Aichi Medical University Hospital (No. 15–087), and the protocol adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. As this was not an interventional study, the IRB granted a waiver of a written informed consent from the patients for this study, based on the ethical guidelines for medical and health research involving human subjects established by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Nevertheless, the IRB requested that we present an outline of this study to the public via the Aichi Medical University website to provide an opportunity for patients to refuse participation. None of the patients declined participation. Patient records were anonymized prior to analysis.

The presence of the vertical lower eyelid laxity was judged by a sign of fornix fat prolapse while pulling the lower eyelid margin to the level of the inferior orbital rim.3 The horizontal lower eyelid laxity was evaluated with a pinch test, and medial and lateral distraction tests, as well as a snap-back test. The pinch test was judged as positive when the distance of the lower eyelid margin and the globe was more than 8 mm during anterior lower eyelid pulling.1, 9 A positive for the medial distraction test was defined as the lower punctum pulled beyond the midpoint of the lacrimal caruncle during medial lower eyelid pulling.1, 9 When the lower punctum was pulled beyond the midpoint between the plica and medial corneal limbus during lateral lower eyelid pulling, the lateral distraction test was judged as positive.1 The snap-back test was significant when the lower eyelid returned to the normal position with several blinks after an examiner pulled the lower eyelid inferiorly.1, 9

Surgical success was defined as the normal eyelid position without contact of any cilia to the globe at the last follow-up period.1 Conversely, recurrence was defined as turn of the eyelid margin towards the globe with contact of the cilia to the globe.1

The patient age, follow-up period, and surgical time were expressed as the mean±SD. The male to female and right to left ratios were statistically compared using the χ2-test for independent variables. The percentage of patients with a positive result of the eyelid laxity and the surgical success between the groups were compared using the Fisher's exact probability test. Statistical comparisons of patient age, follow-up period, and surgical time were carried out between the groups using Student’s t-test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics, version 22 software (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant in all the tests.

Surgical technique

Posterior layer advancement of the LER

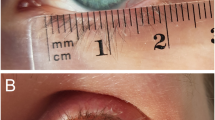

Local anaesthesia with 2 ml of 1% lidocaine and a 1 : 100 000 dilution of epinephrine was administered. A 20 mm skin incision was made horizontally at 3 mm below the cilia (Figure 1a). The layer under the orbicularis oculi muscle (OOM) was dissected towards the cilia. The anterior layer of the LER was detached inferiorly from the tarsal surface until the lower margin of the tarsal plate was exposed. At this point, dissection turned vertically along the lower tarsal edge to expose the conjunctiva. The posterior layer of the LER was then detached from the conjunctiva to 5 mm inferiorly (Figure 1b). At the site 1 mm below the junction of the anterior layer and the orbital septum, the orbital septum was incised transversely (Figure 1c), after which the sheet-like LER were exposed. The OOM in the eyelid margin was slightly debulked to facilitate outward rotation of the eyelid margin. Then, the site 2 mm below the edge of the posterior layer was initially fixed to the lower edge of the tarsal plate using a 6-0 polyvinylidene suture (Asflex, Kono Seisakusho, Chiba, Japan) with simultaneous advancement of the anterior layer as reinforcement for the posterior layer (Figure 1d). This suture is a stronger, smoother, and a more biologically inert material than is a polypropylene suture.10 We added two additional sutures and then the pre-tarsal OOM and the lower edge of the tarsus were secured at three points. Finally, the skin was sutured with 6-0 Asflex sutures.

Posterior layer advancement of the LER in the left lower eyelid. (a) A skin incision line is marked 3 mm below the cilia; (b) The posterior layer of the LER (arrowhead) is detached from the conjunctiva to 5 mm below the lower margin of the tarsus to expose the deep layer of the conjunctiva. The posterior layer is discerned from the anterior layer (arrow); (c) The orbital septum is incised to expose the anterior layer of the LER (arrow); (d) The full-thickness 2 mm advancement of the LER (the anterior layer, arrow; the posterior layer, arrowhead) is achieved.

Transcanthal canthopexy

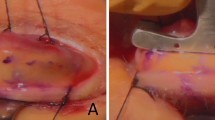

Local anaesthesia with 1 ml of 1% lidocaine and a 1 : 100 000 dilution of epinephrine was administered. A 10 mm skin incision was made along the lateral canthal rhytids, just anterior to the lateral orbital rim (Figure 2a). A stab incision was made at the lateral palpebral commissure or at the lower eyelid margin just medial to the commissure (Figure 2b). Needles with a double-armed 5-0 Prolene suture (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA) were inserted into the stab incision, passed through the periosteum of the lateral orbital rim, and pulled out from the skin incision area (Figure 2c). After a firm ligation of this suture, the skin was closed with 6-0 Asflex sutures (Figure 2d).

Transcanthal canthopexy in the same patient as shown in Figure 1. (a) A 10 mm skin incision line is marked along the lateral canthal rhytids, just anterior to the lateral orbital rim; (b) A stab incision is made at the lower eyelid margin just medial to the commissure; (c) A needle is inserted into the stab incision and pulled out from the skin incision; (d) The skin is closed.

Results

The patients’ data are shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences in the patients’ ages between the groups (P=0.644).1 In Group A, all eyelids showed positive results of the fornix fat prolapse and the medial distraction test before surgery. Positive results of pinch, lateral distraction, and snap-back tests were found in 46, 42, and 36 eyelids, respectively. In Group B, all eyelids showed positive results of the fornix fat prolapse and pinch, medial, and lateral distraction tests before surgery. Positive results of the snap-back test were observed in 43 eyelids. The percentage of patients with positive results of the lateral distraction and snap-back tests were lower in Group A than that in Group B (P<0.050).

All eyelids in both Groups A and B showed successful results without recurrence. The mean follow-up period in Group A was 13.9±9.2 months (range, 6–42 months), which tended to be shorter than that in Group B, although the difference was not significant (17.0±8.4 months, P=0.082).1 The mean surgical time in Group A was 22.4±5.5 min, which was significantly shorter than that in Group B (mean 31.3±4.9 min, P<0.001).1 None of the patients showed lateral canthal deformity after surgery.

Discussion

The LER advancement with transcanthal canthopexy achieved complete surgical success without recurrence. The surgical time of the LER advancement with transcanthal canthopexy was significantly shorter than that of the LER advancement with the LTS.1 In addition, none of the eyelids demonstrated a post-operative lateral canthal deformity in the present study, which occasionally occurred after the LTS.7 Although both combination procedures provided complete surgical success,1 the LER advancement with transcanthal canthopexy is a simpler and safer procedure than the LER advancement with the LTS.

The horizontal lower eyelid tension generally loosens within a certain postoperative period after transcanthal canthopexy,7 because a suture cannot make a long-lasting strong scar. However, none of the patients experienced recurrence in the observational period. Exposure of both the anterior and posterior layers of the LER during LER advancement induces cicatricial shrinkage around the LER in the horizontal direction.11 By adding transcanthal canthopexy, a cicatricial change more widely occurs around the laterally stretched LER. This may help maintain the horizontal tension postoperatively.

None of the previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of transcanthal canthopexy for repair of involutional entropion. Future studies are needed to examine surgical outcomes of combined transcanthal canthopexy and other entropion repairs correcting the vertical eyelid laxity, such as transconjunctival LER advancement,12, 13 the Wies procedure,14 and the Quickert sutures.15

A methodological limitation of the present study is its retrospective design and inclusion of the previously reported patient group. A prospective, randomized study will be necessary to accurately compare the surgical results between the groups. There were fewer eyelids with positive results in the lateral distraction and snap-back tests, and the follow-up period was shorter in Group A than in Group B, which may influence the effectiveness of any comparison between the groups. A future study is necessary to assess the usefulness of transcanthal canthopexy during a longer follow-up period in the aged patient group with the amount of eyelid laxity. Because this study included only Japanese patients, the results may not be applicable to other races. We evaluated the presence of the vertical lower eyelid laxity only by a sign of fornix fat prolapse.3 Examinations of lower eyelid excursion between extreme up and downgaze, the presence or absence of the lower eyelid skin crease, the depth of the inferior fornix, and passive elevation of the centre of the lower eyelid for evaluations of the vertical lower eyelid laxity, may provide more useful information for analysis of the results.3

In conclusion, the LER advancement with transcanthal canthopexy achieved complete surgical success with shorter surgical time without the risk of postoperative canthal deformity, compared with the LER advancement with the LTS.1 The LER advancement with transcanthal canthopexy can be an option for correction of involutional lower eyelid entropion in patients with both vertical and horizontal laxities.

References

Lee H, Takahashi Y, Ichinose A, Kakizaki H . Comparison of surgical outcomes between simple posterior layer advancement of lower eyelid retractors and combination with a lateral tarsal strip procedure for involutional entropion in a Japanese population. Br J Ophthalmol 2014; 98: 1579–1582.

Iuchi T, Takahashi Y, Kang H, Asamura S, Isogai N, Kakizaki H . Involvement of inward upper eyelid push on the lower eyelid during eyelid closure in development of involutional lower eyelid entropion. Eur J Ophthalmol, e-pub ahead of print 16 March 2016; doi:10.5301/ejo.5000770.

Beigi B, Kashkouli MB, Shaw A, Murthy R . Fornix fat prolapse as a sign for involutional entropion. Ophthalmology 2008; 115: 1608–1612.

Kakizaki H, Zhao J, Nakano T, Asamoto K, Zako M, Iwaki M et al. The lower eyelid retractor consists of definite double layers. Ophthalmology 2006; 113: 2346–2350.

Kakizaki H, Chan W, Madge SN, Malhotra R, Selva D . Lower eyelid retractors in Caucasians. Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 1402–1404.

Jordan DR, Anderson RL . The lateral tarsal strip revisited: the enhanced tarsal strip. Arch Ophthalmol 1989; 107: 604–606.

Gladstone HB, Moy RL . Suspension suture canthopexy: a minimally invasive procedure for correcting mild to moderate ectropion. J Cosmet Dermatol 2009; 8: 289–294.

Hamra ST . The zygorbicular dissection in composite rhytidectomy: an ideal midface plane. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998; 102: 1646–1657.

Olver J . Lacrimal assessment. In: Olver J (ed). Colour Atlas of Lacrimal Surgery. Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, 2001, pp 44–47.

http://www.konoseisakusho.jp/en/products/suture/pvdf.html. Accessed on 28 May 2016.

Kakizaki H . Lower eyelid retractors’ advancement for lower eyelid entropion repair. Papers 2011; 51: 94–102.

Khan SJ, Mayer DR . Transconjunctival lower eyelid involutional entropion repair: long-term follow-up and efficacy. Ophthalmology 2002; 109: 2112–2117.

Erb MH, Uzcategui N, Dresner SC . Efficacy and complications of the transconjunctival entropion repair for lower eyelid involutional entropion. Ophthalmology 2006; 113: 2351–2356.

Wies F . Surgical treatment of entropion. J Int Coll Surg 1954; 21 (6.1): 758–760.

Quickert MH, Rathbun E . Suture repair of entropion. Arch Ophthalmol 1971; 85: 304–305.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ishida, Y., Takahashi, Y. & Kakizaki, H. Posterior layer advancement of lower eyelid retractors with transcanthal canthopexy for involutional lower eyelid entropion. Eye 30, 1469–1474 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.150

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.150

This article is cited by

-

Postoperative changes in status of meibomian gland dysfunction in patients with involutional entropion

International Ophthalmology (2020)

-

Involutional lower eyelid entropion: causative factors and therapeutic management

International Ophthalmology (2019)