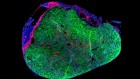

Attitudes in Germany to biological techniques such as genetic modification reflect deep-seated concerns.Credit: Michael Gottschalk/Photothek/Getty

In most parts of the world, including Berlin, you could — if you wished — do some simple molecular-biology tricks in your kitchen. You might, for instance, insert the gene for the green fluorescent protein into harmless Escherichia coli, and cause the bacteria to glow green. But do so in the German state of Bavaria, and you could go to prison.

Germany’s attitudes towards biology can seem inconsistent, but they stem from a deep fear of repeating history. Many of the country’s politicians see biology as a terrifying business. They sense the nervousness of their electorate towards anything that smacks of interfering with nature — the atrocious experiments done on people by the Nazis continue to resonate. Politicians are also exquisitely attuned to the more fundamental, evolutionary fear of unleashing uncontrollable disease.

These concerns present a dilemma because those politicians would also like biology — now a major, highly competitive international business — to contribute to the German economy, and overzealous regulations make the country a less attractive place for scientists to develop it. Strict monitoring and control over experimental biology is non-negotiable: mistakes could lead to catastrophic consequences for health or the environment, should pathogens or, say, invasive plant species accidentally escape from labs. But overextension of these regulations into areas of biology known to be safe is counterproductive.

Although European Union member states are obliged to comply with EU legislation on genetically modified (GM) organisms, they have some flexibility over how those rules are written into their national laws. In Germany, regulations for GM organisms are strict: it is the only country in which infringement can lead to imprisonment of up to three years. And Germany’s federal system leads to another complication, because each of the country’s 16 states hold responsibility for how the rules are implemented.

It’s time the country took a rational look at the inconsistencies that have arisen, and began to do something about it. Help in getting the public to accept this process could come from an unlikely source: do-it-yourself (DIY) biologists, sometimes known as biohackers. Despite an unfair reputation in some quarters for being unpredictable and threatening, many DIY biologists merely want to follow their curiosity independent of the formal culture of institutions. Some are artists who want to express themselves in green fluorescent protein rather than paint, or otherwise engage intellectually with what they see as the most important scientific and societal revolution of our time. Indeed, in doing so, biohackers could help to inject a sense of proportionality into the German public consciousness, with their diverse public displays of safe — and marvellous — biology. And that would help biologists, including those who work on GM organisms, who need public support for their work.

An incident earlier this year exemplifies the role that biohackers can have, and the respect they deserve from authorities and mainstream scientists. Bavarian authorities discovered pathogenic bacteria‚ some antibiotic-resistant, in a CRISPR kit sent from a supplier in California. These kits allow DIY biologists to make small, targeted edits to the genomes of supplied microorganisms. The US company involved, Odin, is a main source for DIY biologists because it markets and sells biological reagents to individuals. The Bavarian authorities sent its analysis of the kit to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), which assessed the risk of infection for healthy users of the supplies and deemed it very low. The three pathogens involved are commonly found in the environment, including the human gut — and the ECDC declared the risk of increasing the burden of multi-drug resistance genes in the environment to be insignificant. Germany has now banned all imports from Odin, except to certified high-safety-level labs. Where the contamination came from is unclear. (Odin did not reply to Nature’s request for comment.)

DIY biologists were appalled to learn of it, not only because experiments could fail if kits don’t contain what they are supposed to, but also because they want to remain working within the law. But they were also frustrated by the refusal of Bavarian authorities to let them see the data — a concern also shared by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg, which agreed to analyse three other samples of microorganisms supplied by Odin and collected by the DIYers from different sources. Scientists at the laboratory cultured one of the bacterial colonies and fully sequenced its genome (the other samples failed to grow). The results, now online, confirm contamination. The effort also highlights the commitment of biohackers to open science and responsible procedures.

Such test cases could help Germany to develop a more rational approach to evaluating the promise and perils of biology — and so encourage a German public perception that biology does not always need to be locked up in a lab.