Abstract

Most tetrapods have retained terrestrial locomotion since it evolved in the Palaeozoic era1,2, but bats have become so specialized for flight that they have almost lost the ability to manoeuvre on land at all3,4. Vampire bats, which sneak up on their prey along the ground, are an important exception. Here we show that common vampire bats can also run by using a unique bounding gait, in which the forelimbs instead of the hindlimbs are recruited for force production as the wings are much more powerful than the legs. This ability to run seems to have evolved independently within the bat lineage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Bats (Chiroptera) are the only mammals that fly, so their bodies differ from those of terrestrial mammals. As a result, most grounded bats can only shuffle awkwardly from a sprawled position4. However, the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) walks forwards, sideways and backwards5, and initiates flight with a single vertical jump from standing6. Captive D. rotundus have also been found to ‘hop’ at speeds exceeding 2.0 metres per second5.

To determine whether this hopping behaviour constitutes a stereotyped running gait by D. rotundus, we tested five adult males on a treadmill inside a Plexiglas cage. The animals used a walking gait at low treadmill speeds (0.12 to 0.56 m s−1) and a stereotyped running gait at high speeds (0.28 to 1.14 m s−1). The walking gait was similar to the typical lateral-sequence walking gait of other tetrapods7; however, the run was different from any gait previously described (Fig. 1; for methods and video, see supplementary information). We classify this novel gait as a run because it includes a notable aerial phase.

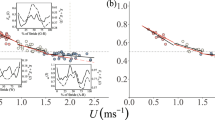

A tetrapod typically increases its speed while walking by increasing its stride frequency. At some transition speed, animals switch to a running gait that permits a further increase in speed, but at stride frequencies that are lower than would be predicted for high-speed walking8,9. Our kinematic data from D. rotundus fit this general stride-frequency–velocity relationship. In Fig. 2, the slopes of the stride-frequency–velocity regressions, which are best fits to the walking and running data, respectively, and are shown truncated at the intersection, are significantly different (t-test, P<0.0001, n=61). These regression lines indicate that common vampire bats, like other running tetrapods, keep their stride frequencies low by walking at low speeds and running at high speeds (Fig. 2).

The walking vampire bats used stride frequencies that were comparable to those of similarly sized terrestrial mammals (mice) over the same range of speeds (Fig. 2; blue line). When running, however, the bats used lower stride frequencies than mice8: this could be explained by the vampire bats' long forearms, which allow longer and fewer strides to be taken during running than can be achieved by mice.

The absence of a running gait in all other bat species so far surveyed indicates that running may have been lost early in the evolution of bats, evolving afresh in the vampires at a later time. We have shown that the hopping behaviour reported for D. rotundus in captivity5 is a running gait. But despite detailed knowledge of their roosting and foraging behaviour10,11, the selective benefit of running for these bats in the wild is not known. Presumably, vampire bats are most likely to run when manoeuvring around prey animals while feeding, and they may have used the gait more before the introduction of domestic livestock to the Americas in the sixteenth century11.

References

Gambaryan, P. P. Zh. Obshch. Biol. 63, 426–445 (2002).

Parchman, A. J., Reilly, S. M. & Biknevicius, A. R. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 1379–1388 (2003).

Vaughan, T. A. Univ. Kansas Publ. Mus. Nat. Hist. 12, 1–153 (1959).

Riskin, D. K., Bertram, J. E. A. & Hermanson, J. W. J. Exp. Biol. (in the press).

Altenbach, J. S. Spec. Publ. Am. Soc. Mammal. 6, 137 (1979).

Schutt, W. A. Jr et al. J. Exp. Biol. 200, 3003–3012 (1997).

Hildebrand, M. in Functional Vertebrate Morphology (eds Hildebrand, M., Bramble, D. M., Liem, K. F. & Wake, D. B.) 38–57 (Belknap, Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1985).

Heglund, N. & Taylor, C. J. Exp. Biol. 138, 301–318 (1988).

Taylor, C., Heglund, N. & Maloiy, G. J. Exp. Biol. 97, 1–21 (1982).

Turner, D. C. The Vampire Bat: A Field Study in Behavior and Ecology (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, 1975).

Greenhall, A. M. & Schmidt, U. Natural History of Vampire Bats (CRC, Boca Raton, 1988).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Riskin, D., Hermanson, J. Independent evolution of running in vampire bats. Nature 434, 292 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/434292a

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/434292a

This article is cited by

-

Terrestrial locomotor behaviors of the big brown bat (Vespertilionidae: Eptesicus fuscus)

Mammal Research (2023)

-

Divergent evolution of terrestrial locomotor abilities in extant Crocodylia

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Science, technology and the future of small autonomous drones

Nature (2015)

-

Vampire bats go with the flow

Lab Animal (2013)

-

Vampire bats have a clear run

Nature (2005)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.