ABSTRACT

The highly conserved Wnt secreted proteins are critical mediators of cell-to-cell signaling during development of animals. Recent biochemical and genetic analyses have led to significant insight into understanding how Wnt signals work. The catalogue of Wnt signaling components has exploded. We now realize that multiple extracellular, cytoplasmic, and nuclear components modulate Wnt signaling. Moreover, receptor-ligand specificity and multiple feedback loops determine Wnt signaling outputs. It is also clear that Wnt signals are required for adult tissue maintenance. Perturbations in Wnt signaling cause human degenerative diseases as well as cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The Wnt family of signaling molecules regulates numerous processes in animal development and has increasingly been implicated in tissue homeostasis in adult organisms. Wnt proteins are secreted from cells and act on target cells through a pathway that, compared to other signaling pathways, is unusually complex and subject to extensive feed-back control. The understanding of this pathway, in particular the central role of β-catenin has historically been mostly based on genetics in model organisms, but is now also supported by biochemical and structural insight. Wnt signals are extremely pleiotropic in their activity, with consequences ranging from mitogenic stimulation to differentiation, changes in polarity and differential cell adhesion. Just like is the case for other embryonic signaling factors, the nature of the response to Wnts is to a very large extent determined by the responding cells. Wnt malfunction is implicated in various forms of disease, including cancer and degenerative diseases. In the light of these findings, it is anticipated that a detailed analysis of Wnt signaling will aid in alleviating these diseases and that Wnt proteins can be developed into important reagents for cell fate control, including stem cells.

WNT GENES, PROTEINS

Wnt genes are defined by sequence, encoding proteins that have a characteristic cysteine pattern plus other conserved residues, rather than by functional properties. The finished genomes of mammals and invertebrate organisms has led to catalogues of 19 Wnt genes in the human and the mouse, 7 in Drosophila, and 5 in C. elegans. Between Drosophila and mammals, there is fairly extensive conservation of Wnt genes, so that orthologs can readily be recognized.

Wnt proteins have only recently been characterized. To some extent, early difficulties in isolating active Wnts are now explained by the finding that Wnt molecules are palmitoylated and therefore much more hydrophobic than predicted from the primary amino acid sequence 1. The palmitoylation is on a cysteine that by mutant analysis is essential for function. Treating Wnt with the enzyme acyl protein thioesterase results in a form that is not hydrophobic anymore, and not active either, strengthening the evidence that the palmitate is important for signaling. Because this cysteine is conserved in all known Wnt proteins, it is likely that all Wnts are palmitoylated. It remains an intriguing question how palmitoylated Wnt molecules are transported. Are there carrier molecules that bind directly to the lipids? Or are the proteins always tethered to membranes, even when shuttled between cells?

WNT RECEPTORS

Our understanding of the reception of Wnt signaling has greatly been improved over the past years. Genetic and biochemical data have led to the consensus view that the Frizzled (Fz) molecules are primary receptors for Wnts 2. Frizzled receptors are 7 transmembrane molecules with a long amino-terminal extension called CRD (cysteine-rich domain). Wnt proteins bind directly to the CRD of Fz 2, 3, 4. Wnt signaling requires not only a functional Fz, but also the presence of a long single pass transmembrane molecule of the LRP (LDL receptor related protein) class, identified as the gene arrow in Drosophila 5 and as LRP5 or 6 in vertebrates. It has been proposed but not always confirmed that Wnt molecules can also bind to LRP and form a trimeric complex with a Frizzled. The cytoplasmic tail of LRP may interact directly with Axin, one of the downstream components in Wnt signaling 6.

HOW DO THE WNT RECEPTORS SIGNAL?

Little is known about the mechanism of action of Frizzled signaling. Binding of ligand may, in analogy with other receptors, lead to a reconfiguration of the transmembrane domains. The overall topology of the Frizzled molecules, in particular the heptahelical signaling domain suggests that these receptors are able to signal through heterotrimeric G proteins. The most direct test of such a mechanism is to add a known Wnt ligand to cells expressing the cognate Frizzled receptor and examine the immediate consequences. For reasons outlined above, experiments along these lines are complicated and several workers have therefore used an indirect approach expressing chimeric receptors. These experiments have suggested that chimeric receptors would signal through a G protein but it remains to be shown that natural Fz molecules couple to a heterotrimeric G protein.

A candidate molecule that may directly interact with Fz is dishevelled. The Dsh gene is known to be required for Wnt signaling 7, 8 and it is genetically upstream of the other known components. Wnt signaling leads to differential phosphorylation of Dsh, a process that is mediated by several protein kinases of which the Par1 kinase is the most likely candidate to be regulated by the signal.

The co-receptor, LRP, may also contact a cytoplasmic component of the pathway, as it has been reported that Axin can interact with the cytoplasmic tail of LRP 6, 9. This suggests that Wnt signaling can lead to the formation of a complex including the two receptors, plus Axin and Dsh. Direct interactions between Axin and Dsh, possibly through the DIX domain that they both contain would then be the first step in reconfiguring the destruction complex containing β-catenin.

WNT SIGNALING WITHIN THE CELL

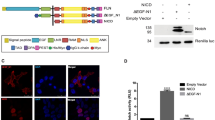

A hallmark of Wnt pathway activation is the elevation of cytoplasmic β-catenin protein levels (Fig. 1). In the absence of Wnt signaling, β-catenin is phosphorylated by the serine/threonine kinases, Casein Kinase 10, 11, 12 and GSK-3 13. The interaction between these kinases and β-catenin is facilitated by the scaffolding proteins, Axin and APC 14, 15. Together, these proteins form α-catenin 'degradation complex,' which allows phosphorylated β-catenin to be recognized by β-TrCP, targeted for ubiquitination, and degraded by the proteosome 16, 17, 18.

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway. In cells not exposed to a Wnt signal (left panel), β-catenin is degraded through interactions with Axin, APC, and the protein kinase GSK-3. Wnt proteins (right panel) bind to the Frizzled/LRP receptor complex at the cell surface. These receptors transduce a signal to Dishevelled (Dsh) and to Axin, which may directly interact (dashed lines). As a consequence, the degradation of β-catenin is inhibited, and this protein accumulates in the cytoplasm and nucleus. β-catenin then interacts with TCF to control transcription.

Activation of Wnt signaling inhibits β-catenin phosphorylation and hence its degradation. The elevation of β-catenin levels leads to its nuclear accumulation and complex formation with LEF/TCF transcription factors. β-catenin mutant forms that lack the phosphorylation sites required for its degradation are Wnt un-responsive and can activate Wnt target genes constitutively 13, 19. β-catenin, APC and Axin mutations that promote β-catenin stabilization are found in many different cancers, indicating that constitutive Wnt signaling is a common feature in many neoplasms (reviewed in 20).

Current approaches to elucidate the mechanisms of catenin regulation include attempts to determine the structure of the degradation complex. There are now crystallographic structures of Axin contacting catenin 21 and Axin bound to APC 22.

SIGNALING IN THE NUCLEUS

The increased stability of β-catenin following Wnt signaling leads to the transcriptional activation of target genes in the nucleus. This is regulated by the β-catenin interactions with the TCF/LEF DNA binding proteins. In the absence of the Wnt signal, TCF acts as a repressor of Wnt/Wg target genes 23, by forming a complex with Groucho 24. The repressing effect of Groucho is mediated by interactions with Histone Deacetylases (HDAC), which are thought to make DNA refractive to transcriptional activation 25.

Once in the nucleus, β-catenin is thought to convert the TCF repressor complex into a transcriptional activator complex. This may occur through displacement of Groucho from TCF/LEF and recruitment of the histone acetylase CBP/p300. CBP may bind to the β-catenin-TCF complex as a co-activator 26, 27, a hypothesis that remains to be tested directly. Another activator, Brg-1, is a component of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex which, with CBP, may induce chromatin remodeling that favors target gene transcription 28.

Further interactions between the β-catenin-TCF complex and chromatin could be mediated by Legless (Bcl9) and Pygopos 29, 30, 31. Mutations in either of these genes result in wingless-like phenotypes in Drosophila, and both genes promote Wnt signaling in mammalian cell culture experiments 30.

ACTIVATION AND REPRESSION OF TARGET GENES

The Wnt pathway has numerous transcriptional endpoints. The large majority of these is cell type specific, i.e. are only activated in certain cells. This specificity is commonly seen in developmental signaling pathways, and reflects the fundamental mechanism of gene control by extracellular signals: the cell rather than the signal determines the nature of the response. But in addition to the cell type specific genes, Wnt signaling also controls genes that are more widely induced. Interestingly, this set of genes include many components of the pathway itself, or among them are genes that are most likely directly activated by the Wnt-β-catenin-TCF cascade

WNT SIGNALING IN CANCER AND HUMAN DISEASE

Given the diverse phenotypes produced by Wnt knock-outs in mice, it is not surprising that loss of Wnts in humans has dire consequences as well. Recently, Tetra-amelia, a rare human genetic disorder characterized by absence of limbs, has been proposed to result from WNT3 loss of function mutations 32.

In adults, mis-regulation of the Wnt pathway also leads to a variety of abnormalities and disease. An LRP mutation has been identified that causes increased bone density at defined locations such as the jaw and palate 33, 34. The mutation is a single amino-acid substitution that makes LRP5 insensitive to Dkk-mediated Wnt pathway inhibition, indicating that the phenotype results from over-active Wnt signaling in the bone 34. In a different study, mutations in LRP5 were correlated with decreased bone mass 35. In this case, frame shift and missense mutations were thought to create loss-of-function LRP5 mutations. These data indicate that Wnt signaling mediated by LRP5 is required for maintenance of normal bone density.

Mutations that promote constitutive activation of the Wnt signaling pathway lead to cancer. The best-known example is Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), an autosomal, dominantly inherited disease in which patients display polyps in the colon and rectum. This disease is caused most frequently by truncations in APC 36, 37 that promote aberrant activation of the Wnt pathway leading to adenomatous lesions due to increased cell proliferation. Mutations in β-catenin and APC have also been found in sporadic colon cancers and a large variety of other tumor types (reviewed in 20). Loss-of-function mutations in Axin have been found in hepatocellular carcinomas 38. These examples demonstrate that the uncoupling of normal β-catenin regulation from Wnt signaling control is an important event in the genesis of many cancers.

It has become increasingly common to view cancer as a “stem cell” disease (see 39). In the colon, loss of TCF4 or Dkk over-expression promotes loss of stem cells in the colon crypt, indicating that Wnt signaling is required for maintenance of the stem cell compartment 40, 41, 42. Wnt signaling may therefore be a fundamental regulator of stem cell choices to proliferate or self-renew.

References

Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, et al. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature 2003; 423:448–52.

Bhanot P, Brink M, Samos CH et al. Links A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a Wingless receptor. Nature 1996; 382:225–30.

Hsieh JC, Rattner A, Smallwood PM et al. Biochemical characterization of Wnt-frizzled interactions using a soluble, biologically active vertebrate Wnt protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96:3546–51.

Dann CE, Hsieh JC, Rattner A et al. Insights into Wnt binding and signalling from the structures of two Frizzled cysteine-rich domains. Nature 2001; 412:86–90.

Wehrli M, Dougan ST, Caldwell K, et al. Arrow encodes an LDL-receptor-related protein essential for Wingless signalling. Nature 2000; 407:527–30.

Tolwinski NS, Wehrli M, Rives A, et al. Wg/Wnt signal can be transmitted through arrow/LRP5,6 and Axin independently of Zw3/Gsk3beta activity. Dev Cell 2003; 4:407–18.

Chen W, ten Berge D, Brown J, et al. Dishevelled 2 recruits beta-arrestin 2 to mediate Wnt5A-stimulated endocytosis of Frizzled 4. Science 2003; 301:1391–1394.

Wong HC, Bourdelas A, Krauss A, et al. Direct binding of the PDZ domain of Dishevelled to a conserved internal sequence in the C-terminal region of Frizzled. Mol Cell 2003; 12:1251–60.

Mao J, Wang J, Liu B, et al. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-5 binds to Axin and regulates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Mol Cell 2001; 7:801–9.

Amit S, Hatzubai A, Birman Y, et al. Axin-mediated CKI phosphorylation of beta-catenin at Ser 45: a molecular switch for the Wnt pathway. Genes Dev 2002; 16:1066–76.

Liu C, Li Y, Semenov M, et al. Control of beta-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell 2002; 108:837–47.

Yanagawa S, Matsuda Y, Lee JS, et al. Casein kinase I phosphorylates the Armadillo protein and induces its degradation in Drosophila. Embo J 2002; 21:1733–42.

Yost C, Torres M, Miller JR, et al. The axis-inducing activity, stability, and subcellular distribution of beta-catenin is regulated in Xenopus embryos by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Genes Dev 1996; 10:1443–54.

Hart MJ, de los Santos R, Albert IN, et al. Downregulation of beta-catenin by human Axin and its association with the APC tumor suppressor, beta-catenin and GSK3 beta. Curr Biol 1998; 8:573–81.

Kishida S, Yamamoto H, Ikeda S, et al. Axin, a negative regulator of the wnt signaling pathway, directly interacts with adenomatous polyposis coli and regulates the stabilization of beta-catenin. J Biol Chem 1998; 273:10823–6.

Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, et al. beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Embo J 1997; 16:3797–804.

Latres E, Chiaur DS, Pagano M . The human F box protein beta-Trcp associates with the Cul1/Skp1 complex and regulates the stability of beta-catenin. Oncogene 1999; 18:849–54.

Liu C, Kato Y, Zhang Z, et al. beta-Trcp couples beta-catenin phosphorylation-degradation and regulates Xenopus axis formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96:6273–8.

Munemitsu S, Albert I, Rubinfeld B, et al. Deletion of an amino-terminal sequence beta-catenin in vivo and promotes hyperphosporylation of the adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor protein. Mol Cell Biol 1996; 16:4088–94.

Giles RH, van Es JH, Clevers H . Caught up in a Wnt storm: Wnt signaling in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003; 1653:1–24.

Xing Y, Clements WK, Kimelman D, et al. Crystal structure of a beta-catenin/axin complex suggests a mechanism for the beta-catenin destruction complex. Genes Dev 2003; 17:2753–64.

Spink KE, Polakis P, Weis WI . Structural basis of the Axin-adenomatous polyposis coli interaction. Embo J 2000; 19:2270–9.

Brannon M, Gomperts M, Sumoy L, et al. A beta-catenin/XTcf-3 complex binds to the siamois promoter to regulate dorsal axis specification in Xenopus. Genes Dev 1997; 11:2359–70.

Cavallo RA, Cox RT, Moline MM, et al. Drosophila Tcf and Groucho interact to repress Wingless signalling activity. Nature 1998; 395:604–8.

Chen G, Fernandez J, Mische S, et al. A functional interaction between the histone deacetylase Rpd3 and the corepressor groucho in Drosophila development. Genes Dev 1999; 13:2218–30.

Hecht A, Vleminckx K, Stemmler MP, et al. The p300/CBP acetyltransferases function as transcriptional coactivators of beta-catenin in vertebrates. Embo J 2000; 19:1839–50.

Takemaru KI, Moon RT . The transcriptional coactivator CBP interacts with beta-catenin to activate gene expression. J Cell Biol 2000; 149:249–54.

Barker N, Hurlstone A, Musisi H, et al. The chromatin remodelling factor Brg-1 interacts with beta-catenin to promote target gene activation. Embo J 2001; 20:4935–43.

Kramps T, Peter O, Brunner E, et al. Wnt/wingless signaling requires BCL9/legless-mediated recruitment of pygopus to the nuclear beta-catenin-TCF complex. Cell 2002; 109:47–60.

Thompson B, Townsley F, Rosin-Arbesfeld R, et al. A new nuclear component of the Wnt signalling pathway. Nat Cell Biol 2002; 4: 367–73.

Parker DS, Jemison J, Cadigan KM . Pygopus, a nuclear PHD-finger protein required for Wingless signaling in Drosophila. Development 2002; 129:2565–76.

Niemann S, Zhao C, Pascu F, et al. Homozygous WNT3 mutation causes tetra-amelia in a large consanguineous family. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 74:558–63.

Little RD, Carulli JP, Del Mastro RG, et al. A mutation in the LDL receptor-related protein 5 gene results in the autosomal dominant high-bone-mass trait. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 70:11–9.

Boyden LM, Mao J, Belsky J, et al. High bone density due to a mutation in LDL-receptor-related protein 5. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1513–21.

Gong Y, Slee RB, Fukai N, et al. LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell 2001; 107:513–23.

Kinzler KW, Nilbert MC, Su LK, et al. Identification of FAP locus genes from chromosome 5q21. Science 1991; 253: 661–5.

Nishisho I, Nakamura Y, Miyoshi Y, et al. Mutations of chromosome 5q21 genes in FAP and colorectal cancer patients. Science 1991; 253:665–9.

Satoh S, Daigo Y, Furukawa Y, et al. AXIN1 mutations in hepatocellular carcinomas, and growth suppression in cancer cells by virus-mediated transfer of AXIN1. Nat Genet 2000; 24:245–50.

Taipale J, Beachy PA . The Hedgehog and Wnt signalling pathways in cancer. Nature 2001; 411:349–54.

Korinek V, Barker N, Moerer P, et al. Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat Genet 1998; 19:379–83.

Pinto D, Gregorieff A, Begthel H, et al. Canonical Wnt signals are essential for homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium. Genes Dev 2003; 17:1709–13.

Kuhnert F, Davis CR, Wang HT, et al. Essential requirement for Wnt signaling in proliferation of adult small intestine and colon revealed by adenoviral expression of Dickkopf-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101:66–71.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

NUSSE, R. Wnt signaling in disease and in development. Cell Res 15, 28–32 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cr.7290260

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cr.7290260

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hippocampal dentate gyri proteomics reveals Wnt signaling involvement in the behavioral impairment in the THRSP-overexpressing ADHD mouse model

Communications Biology (2023)

-

Computational evaluation of bioactive compounds from Vitis vinifera as a novel β-catenin inhibitor for cancer treatment

Bulletin of the National Research Centre (2022)

-

DVL1 and DVL3 require nuclear localisation to regulate proliferation in human myoblasts

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

The role of Wnt pathway antagonists in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma

Molecular Biology Reports (2022)

-

CENPA promotes clear cell renal cell carcinoma progression and metastasis via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

Journal of Translational Medicine (2021)