Abstract

Background:

Some components of the Mediterranean diet have favourable effects on endometrial cancer, and the Mediterranean diet as a whole has been shown to have a beneficial role on various neoplasms.

Methods:

We analysed this issue pooling data from three case-control studies carried out between 1983 and 2006 in various Italian areas and in the Swiss Canton of Vaud. Cases were 1411 women with incident, histologically confirmed endometrial cancer, and controls were 3668 patients in hospital for acute diseases. We measured the adherence to the Mediterranean diet using a Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS), based on the nine dietary components characteristics of this diet, that is, high intake of vegetables, fruits/nuts, cereals, legumes, fish; low intake of dairy products and meat; high monounsaturated to saturated fatty acid ratio; and moderate alcohol intake. We estimated the odds ratios (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for increasing levels of the MDS (varying from 0, no adherence, to 9, maximum adherence) using multiple logistic regression models, adjusted for major confounding factors.

Results:

The adjusted OR for a 6–9 components of the MDS (high adherence) compared with 0–3 (low adherence) was 0.43 (95% CI 0.34–0.56). The OR for an increment of one component of MDS diet was 0.84 (95% CI 0.80–0.88). The association was consistent in strata of various covariates, although somewhat stronger in older women, in never oral contraceptive users and in hormone-replacement therapy users.

Conclusions:

Our study provides evidence for a beneficial role of the Mediterranean diet on endometrial cancer risk, suggesting a favourable effect of a combination of foods rich in antioxidants, fibres, phytochemicals, and unsaturated fatty acids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Although the most important determinant of endometrial cancer is elevated oestrogen levels (Liang and Shang, 2013), diet has been shown to have a role in the prevention of this neoplasm, possibly modifying oestrogen availability (Gaskins et al, 2009; World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research, 2013).

The Mediterranean diet, typical of selected areas of the Mediterranean basin (including Italy, Southern France, Greece, Spain and Morocco), is characterised by frequent consumption of various vegetables and fruit, cereals, fish and seafood, use of olive oil as the main seasoning fat, moderate alcohol (preferably in the form of wine) consumption, and relatively low consumption of meat and dairy products. Several epidemiological studies investigated the role of single food items characteristic of the Mediterranean diet on endometrial cancer risk, showing that high intake of vegetables and fruit (Bandera et al, 2007b), fibres and antioxidant vitamins (Goodman et al, 1997; Horn-Ross et al, 2003), cereals (La Vecchia et al, 1986; Potischman et al, 1993), legumes (Petridou et al, 2002) and fish (Brasky et al, 2014) has a favourable effect on the risk of this neoplasm, whereas high intakes of total, saturated and animal fat (Bandera et al, 2007a; Bravi et al, 2009), milk and dairy products (Ganmaa et al, 2012) increase the risk.

However, various components of the Mediterranean diet may act synergistically, leading to an overall effect greater than the sum of single foods, as found for other neoplasms, such as those of the oral cavity and pharynx (Bosetti et al, 2003; Filomeno et al, 2014), oesophagus (Bosetti et al, 2003), stomach (Praud et al, 2014), liver (Turati et al, 2014), pancreas (Bosetti et al, 2013) and larynx (Bosetti et al, 2003).

It has been estimated that about 10% of the incident endometrial cancers could be prevented if Western populations could shift their diet to the traditional Mediterranean diet (Trichopoulou et al, 2000). However, in a cohort of American women there was no relation between endometrial cancer risk and a recommended dietary score, based on the intake of 23 foods including a few components of Mediterranean diet such as fruit, vegetables, white meat, fish and whole grains (Mai et al, 2005). No reduction of endometrial cancer was found also in the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Randomized Controlled Trial, whose goal was to reduce total fat intake and to increase intake of fruit, vegetables and grains (Prentice et al, 2007). An American case-control study considering four a posteriori defined dietary patterns (named ‘plant-based’, ‘western’, ‘ethnic’ and ‘phytoestrogen rich’) found no relation between any of these and endometrial cancer risk, although a diet characterised by a high fat consumption increased the risk (Dalvi et al, 2007). A Canadian case-control study found a weak inverse relation between endometrial cancer risk and a diet rich in plant foods and no relation with diets rich in sweets and meat (Biel et al, 2011).

Given the traditional high adherence to the Mediterranean diet of the Italian population, we investigated such issue pooling data from three case-control studies conducted in Italy and in the French speaking Switzerland, using a simple and intuitive a priori score of adherence to the Mediterranean diet proposed in the literature.

Materials and Methods

Participants and study design

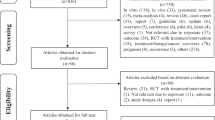

We analysed data from three case-control studies on endometrial cancer, conducted by the same group using similar protocols and questionnaires. Briefly, the first study was conducted in the greater Milan area and the provinces of Pordenone and Udine, Northern Italy, between 1982 and 1995 (La Vecchia et al, 1991), and included 538 cases of endometrial cancer and 2122 controls; the second study was conducted in the Swiss Canton of Vaud and in Northern Italy between 1988 and 1994 (Negri et al, 1996), and included 466 cases of endometrial cancer and 792 controls; and the third study was conducted in the greater Milan area and the provinces of Pordenone and Udine, in northern Italy, and the urban area of Naples, in southern Italy, between 1992 and 2006, and included 454 cases and 908 controls (Bravi et al, 2009). Cases were a total of 1458 women (median age 61 years) with incident, histologically confirmed endometrial cancer, admitted to the major teaching and general hospitals of the study areas; controls were 3822 women (median age 57 years) admitted to the same network of hospitals as cases for a wide spectrum of acute non-neoplastic conditions. Among controls, 29% were admitted for traumatic conditions, 29% for non-traumatic orthopaedic diseases, 18% for acute surgical conditions and 24% for other miscellaneous illnesses. Informed consent was obtained from each patient according to the local ethical rules. Among cases and controls approached, <5% in Italy and 10% in Switzerland refused the interview. Since for 47 cases and 154 controls information was missing for at least one dietary item of interest (with the exception of legumes, for which the information was not available in the first study), our analyses were based on a total number of 1411 cases and 3668 controls.

Trained interviewers identified and questioned cases and controls in hospital, using structured questionnaire. These included information on socio-demographic and anthropometric characteristics, tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, personal medical history, menstrual and reproductive factors, use of oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone-replacement therapy. Information on patients’ usual diet in the 2 years before diagnosis was based on food frequency questionnaires, collecting information on weekly consumption of 14 selected indicator foods in the first study (La Vecchia et al, 1991), 50 foods in the second study (Negri et al, 1996) and 78 dietary items in the most recent study (Bravi et al, 2009). Intakes lower than once a week, but 1–3 times a month, were coded as 0.5 per week. The first two questionnaires have been shown to have a satisfactory reproducibility (D'Avanzo et al, 1997) and the most recent one a good reproducibility (Franceschi et al, 1995) and validity (Decarli et al, 1996) with the Spearman correlation coefficients between 0.60 and 0.80 for most food items considered in the Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS).

Dietary score

We used an a priori MDS based on nine characteristics of the traditional Mediterranean diet (Trichopoulou et al, 1995), that is, high consumption of fruit/nuts, vegetables, cereals (including bread and potatoes), legumes (for the second and third study only) and fish; high monounsaturated/saturated fatty acid ratio; low consumption of meat (including meat products) and milk (including dairy products); and moderate intake of alcohol (mainly wine). Subjective scores (low, medium and high) were used to obtain information on whole grain cereals in the first study and on monounsaturated and saturated fats in the first and second study. The study-specific median values according to the distribution of controls were used as cut-off points, for defining high and low intake of the nine components. A value of 1 or 0 was attributed to each subject for the presence of each characteristic. Thus, value 1 was given to: intake above median for fruit/nuts, vegetables, cereals, legumes, fish and high monounsaturated/saturated fatty acid ratio; intake below median for meat/meat products and milk/dairy products; and moderate consumption for alcohol, defined as intake over zero and below the study-specific median intake. The MDS was defined as the sum of the 9 individual binary components, and ranged between 0 (no adherence to the Mediterranean diet) and 9 (maximum adherence).

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) of endometrial cancer were computed for categories of the MDS using unconditional multiple logistic regression models (Breslow and Day, 1980). These included terms for age (quinquennia; categorically), study centre (Milan, Pordenone/Udine, Naples and Vaud), year of interview (continuous), education (<7, 7–<12, ⩾12 years; categorically), body mass index (BMI, <21, 21–<25, 25–<30, ⩾30 kg m−2; categorically), tobacco smoking (never, ex-smoker and current smoker of <14 or ⩾14 cigarettes per day; categorically), total energy intake (quintiles; categorically), number of children (0, 1, >1; categorically), menopausal status/age at menopause (pre/perimenopausal, <50, ⩾50 years; categorically), age at menarche (<12, 12–<13, >13 years; categorically), oral contraceptive use (never/ever), hormone-replacement therapy use (never/ever), history of hypertension (yes/no) and diabetes (yes/no). We also computed the OR for an increment of one component of the MDS. Analyses were conducted to investigate whether the association of the MDS with endometrial cancer risk was heterogeneous across strata of selected covariates.

All the analyses were performed using the SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The distribution of 1411 endometrial cancer cases and 3668 controls according to age and other potential confounders is reported in Table 1. Cases were older, had a higher BMI, reported more frequently a history of diabetes and hypertension, had a younger age at menarche and an older age at menopause, were more frequently never smokers, and never users of oral contraceptives and ever users of hormone-replacement therapy.

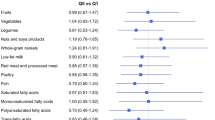

Table 2 shows the adjusted ORs of endometrial cancer risk for each component of the MDS. High vs low consumption of vegetables (OR 0.64), fruit/nuts (0.85) and monounsaturated to saturated fatty acid ratio (0.73), low vs high consumption of meat/meat (0.77) and moderate vs no/high alcohol consumption (0.76) were associated to a significant reduced risk of endometrial cancer, while high consumption of legumes (1.26) and low consumption of milk and dairy products (1.19) were associated to a significant increased risk. No significant association was found for high vs low consumption of cereals and potatoes (OR 0.99) or fish (1.00).

The distribution of endometrial cancer cases and controls and the corresponding ORs according to the MDS are given in Table 3. Compared with a 0–3 components of the MDS, the OR decreased for increasing levels of the MDS, with an OR of 0.43 (95% CI 0.34–0.56) for 7–9 MDS with a significant trend in risk (P for trend <0.0001). The OR for an increment of one unit of the MDS, that is, one component of the Mediterranean diet, was 0.84 (95% CI 0.80–0.88).

The association between the increment of one unit of the MDS and endometrial cancer risk were analysed in strata of selected covariates (Table 4). Risk estimates were consistent across strata of education, BMI, tobacco smoking, history of diabetes and hypertension, age at menarche, parity and age at menopause, while the association was significantly stronger in the second study (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.69–0.84), in women aged ⩾60 years (0.80, 0.75–0.85), in never oral contraceptive users (0.83, 0.78–0.87) and in ever hormone-replacement therapy users (OR 0.70, 0.58–0.83).

Discussion

In the present study, based on a large case-control investigation, we found a reduced risk of endometrial cancer for increasing adherence to the Mediterranean diet, with an over 50% risk reduction for women in the highest vs the lowest score. Considering the single components of the Mediterranean diet, we found significant inverse associations only for high consumption of vegetables and fruit, high ratio of monounsaturated to saturated fatty acids, low intake of meat and moderate alcohol consumption. For milk and legumes, we found associations even opposite to those expected. This clearly supports the hypothesis that Mediterranean diet as a whole is a stronger determinant of endometrial cancer risk than the single dietary components, probably because dietary score take into account the interactions among various combinations of foods and nutrients and their synergistic effects.

Our results show a greater favourable effect of the Mediterranean diet on endometrial cancer risk than that found in previous investigations (Mai et al, 2005; Dalvi et al, 2007; Prentice et al, 2007). This possibly depends, at least in part, on the definition of the MDS (Trichopoulou et al, 1995). In fact, the MDS is defined as a score in relation to the median consumption of selected foods in the population of controls and not in absolute terms (i.e., amount of foods in grams). However, subjects with a higher MDS score in this Italian population are likely to have higher absolute intake of Mediterranean food components as compared with other populations, as in Italy consumption of the various components of the Mediterranean diet is traditionally higher.

The Mediterranean diet is rich in vitamins, carotenoids, flavonoids and folates (mainly derived from vegetables and fruit), which have shown inverse relations with endometrial cancer in most case-control studies, although no relation in prospective ones (Jain et al, 2000; Pelucchi et al, 2008; Bandera et al, 2009; Bidoli et al, 2010; Cui et al, 2011; Aarestrup et al, 2012; Harris et al, 2012; Tavani et al, 2012). These compounds are rich in antioxidants and have anticarcinogenic properties. Moreover, foods characteristic of the Mediterranean diet are also rich in fibres, which have been involved in oestrogen metabolism (Xu et al, 2007). High intake of fibres decreases serum oestrogen levels (Rose, 1990) and vegetarian women have lower plasma oestrogen levels and lower urinary excretion of estrogens than omnivores (Goldin et al, 1982; Gorbach and Goldin, 1987), thus lowering the risk of endometrial cancer (Key and Pike, 1988). Moreover, a large proportion of energy intake in the Mediterranean diet derives from cereals and other plant sources, which has been inversely related with endometrial cancer risk rather than from animal sources, with a high content of saturated fats (Xu et al, 2007). Dietary fats (mainly saturated from animal sources) may influence the metabolism of oestrogens by increasing the intestinal re-absorption of oestrogens (Gorbach and Goldin, 1987) (and consequently their serum levels) and, thus, the risk of endometrial cancer (Key and Pike, 1988). This is in agreement with the protective effect found in our study for a high unsaturated to saturated fat ratio. The direct association of red meat intake with cancer risk has been attributed to heterocyclic amines, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and nitrosamines produced during cooking, though the interpretation remains open to discussion (Tavani et al, 2000).

The effect of Mediterranean diet on endometrial cancer seems to be independent from its eventual effect on body weight, as Mediterranean diet has not been related with BMI and waist-to-hip ratio (Rossi et al, 2008). However, we carefully allowed for BMI in our analyses.

Limitations of this study are those of all case-control studies, including selection and information bias (Breslow and Day, 1980). However, the participation rates were high and similar between cases and controls and the catchment area was also comparable. The study was hospital-based, but we excluded from controls all subjects with admission diagnosis related to known risk factors for endometrial cancer and hormonal disorders, and information from hospital patients has shown satisfactory reproducibility (D'Avanzo et al, 1997). Dietary habits of hospital controls may not be representative of the general population, but we have also excluded women with chronic conditions which may have altered diet or body weight. We used two food frequency questionnaires tested for reproducibility (Franceschi et al, 1993; D'Avanzo et al, 1997) and validity (Decarli et al, 1996) and there is no reason for a different recall between cases and controls, as both were interviewed in the same hospital setting. We used an a priori developed and commonly used MDS (Trichopoulou et al, 2003). Our risk estimates were allowed for many confounding variables, including endogenous and exogenous hormonal factors and body weight, and the consistency of the direct association through most strata of covariates excludes a major role of residual confounding. The strength of the inverse association, the observed linear relation between risk and exposure, and the biological plausibility support a causality of the relation, although the evidence is still scanty and needs to be confirmed in other studies mainly prospective ones.

In conclusion, our data suggest that a Mediterranean dietary pattern, more than single foods, may favourably influence the risk of endometrial cancer. This supports the hypothesis that a diet rich in a combination of vegetables, fruit and cereals, poor in saturated fats, meat and dairy product, and with a moderate intake of wine has a favourable role on endometrial cancer risk.

Change history

26 May 2015

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Aarestrup J, Kyro C, Christensen J, Kristensen M, Wurtz AM, Johnsen NF, Overvad K, Tjonneland A, Olsen A (2012) Whole grain, dietary fiber, and incidence of endometrial cancer in a Danish cohort study. Nutr Cancer 64: 1160–1168.

Bandera EV, Kushi LH, Moore DF, Gifkins DM, McCullough ML (2007a) Dietary lipids and endometrial cancer: the current epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Causes Control 18: 687–703.

Bandera EV, Kushi LH, Moore DF, Gifkins DM, McCullough ML (2007b) Fruits and vegetables and endometrial cancer risk: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer 58: 6–21.

Bandera EV, Williams MG, Sima C, Bayuga S, Pulick K, Wilcox H, Soslow R, Zauber AG, Olson SH (2009) Phytoestrogen consumption and endometrial cancer risk: a population-based case-control study in New Jersey. Cancer Causes Control 20: 1117–1127.

Bidoli E, Pelucchi C, Zucchetto A, Negri E, Dal Maso L, Polesel J, Montella M, Franceschi S, Serraino D, La Vecchia C, Talamini R (2010) Fiber intake and endometrial cancer risk. Acta Oncol 49: 441–446.

Biel RK, Friedenreich CM, Csizmadi I, Robson PJ, McLaren L, Faris P, Courneya KS, Magliocco AM, Cook LS (2011) Case-control study of dietary patterns and endometrial cancer risk. Nutr Cancer 63: 673–686.

Bosetti C, Gallus S, Trichopoulou A, Talamini R, Franceschi S, Negri E, La Vecchia C (2003) Influence of the Mediterranean diet on the risk of cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12: 1091–1094.

Bosetti C, Turati F, Dal Pont A, Ferraroni M, Polesel J, Negri E, Serraino D, Talamini R, La Vecchia C, Zeegers MP (2013) The role of Mediterranean diet on the risk of pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 109: 1360–1366.

Brasky TM, Neuhouser ML, Cohn DE, White E (2014) Associations of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and fish intake with endometrial cancer risk in the VITamins And Lifestyle cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 99: 599–608.

Bravi F, Scotti L, Bosetti C, Zucchetto A, Talamini R, Montella M, Greggi S, Pelucchi C, Negri E, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C (2009) Food groups and endometrial cancer risk: a case-control study from Italy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200: 293 e291–e297.

Breslow NE, Day NE (1980) Statistical Methods in Cancer Research. Vol. I. The Analysis of Case-Control Studies pp 32. IARC: Lyon, France.

Cui X, Rosner B, Willett WC, Hankinson SE (2011) Dietary fat, fiber, and carbohydrate intake in relation to risk of endometrial cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20: 978–989.

D'Avanzo B, La Vecchia C, Katsouyanni K, Negri E, Trichopoulos D (1997) An assessment, and reproducibility of food frequency data provided by hospital controls. Eur J Cancer Prev 6: 288–293.

Dalvi TB, Canchola AJ, Horn-Ross PL (2007) Dietary patterns, Mediterranean diet, and endometrial cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control 18: 957–966.

Decarli A, Franceschi S, Ferraroni M, Gnagnarella P, Parpinel MT, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Salvini S, Falcini F, Giacosa A (1996) Validation of a food-frequency questionnaire to assess dietary intakes in cancer studies in Italy. Results for specific nutrients. Ann Epidemiol 6: 110–118.

Filomeno M, Bosetti C, Garavello W, Levi F, Galeone C, Negri E, La Vecchia C (2014) The role of a Mediterranean diet on the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Br J Cancer 111: 981–986.

Franceschi S, Barbone F, Negri E, Decarli A, Ferraroni M, Filiberti R, Giacosa A, Gnagnarella P, Nanni O, Salvini S, La Vecchia C (1995) Reproducibility of an Italian food frequency questionnaire for cancer studies. Results for specific nutrients. Ann Epidemiol 5: 69–75.

Franceschi S, Negri E, Salvini S, Decarli A, Ferraroni M, Filiberti R, Giacosa A, Talamini R, Nanni O, Panarello G (1993) Reproducibility of an Italian food frequency questionnaire for cancer studies: results for specific food items. Eur J Cancer 29A: 2298–2305.

Ganmaa D, Cui X, Feskanich D, Hankinson SE, Willett WC (2012) Milk, dairy intake and risk of endometrial cancer: a 26-year follow-up. Int J Cancer 130: 2664–2671.

Gaskins AJ, Mumford SL, Zhang C, Wactawski-Wende J, Hovey KM, Whitcomb BW, Howards PP, Perkins NJ, Yeung E, Schisterman EF (2009) Effect of daily fiber intake on reproductive function: the BioCycle Study. Am J Clin Nutr 90: 1061–1069.

Goldin BR, Adlercreutz H, Gorbach SL, Warram JH, Dwyer JT, Swenson L, Woods MN (1982) Estrogen excretion patterns and plasma levels in vegetarian and omnivorous women. N Engl J Med 307: 1542–1547.

Goodman MT, Wilkens LR, Hankin JH, Lyu LC, Wu AH, Kolonel LN (1997) Association of soy and fiber consumption with the risk of endometrial cancer. Am J Epidemiol 146: 294–306.

Gorbach SL, Goldin BR (1987) Diet and the excretion and enterohepatic cycling of estrogens. Prev Med 16: 525–531.

Harris HR, Cramer DW, Vitonis AF, DePari M, Terry KL (2012) Folate, vitamin B(6), vitamin B(12), methionine and alcohol intake in relation to ovarian cancer risk. Int J Cancer 131: E518–E529.

Horn-Ross PL, John EM, Canchola AJ, Stewart SL, Lee MM (2003) Phytoestrogen intake and endometrial cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 95: 1158–1164.

Jain MG, Howe GR, Rohan TE (2000) Nutritional factors and endometrial cancer in Ontario, Canada. Cancer Control 7: 288–296.

Key TJ, Pike MC (1988) The dose-effect relationship between 'unopposed' oestrogens and endometrial mitotic rate: its central role in explaining and predicting endometrial cancer risk. Br J Cancer 57: 205–212.

La Vecchia C, Decarli A, Fasoli M, Gentile A (1986) Nutrition and diet in the etiology of endometrial cancer. Cancer 57: 1248–1253.

La Vecchia C, Parazzini F, Negri E, Fasoli M, Gentile A, Franceschi S (1991) Anthropometric indicators of endometrial cancer risk. Eur J Cancer 27: 487–490.

Liang J, Shang Y (2013) Estrogen and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol 75: 225–240.

Mai V, Kant AK, Flood A, Lacey JV Jr., Schairer C, Schatzkin A (2005) Diet quality and subsequent cancer incidence and mortality in a prospective cohort of women. Int J Epidemiol 34: 54–60.

Negri E, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, Levi F, Parazzini F (1996) Intake of selected micronutrients and the risk of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer 77: 917–923.

Pelucchi C, Dal Maso L, Montella M, Parpinel M, Negri E, Talamini R, Giudice A, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C (2008) Dietary intake of carotenoids and retinol and endometrial cancer risk in an Italian case-control study. Cancer Causes Control 19: 1209–1215.

Petridou E, Kedikoglou S, Koukoulomatis P, Dessypris N, Trichopoulos D (2002) Diet in relation to endometrial cancer risk: a case-control study in Greece. Nutr Cancer 44: 16–22.

Potischman N, Swanson CA, Brinton LA, McAdams M, Barrett RJ, Berman ML, Mortel R, Twiggs LB, Wilbanks GD, Hoover RN (1993) Dietary associations in a case-control study of endometrial cancer. Cancer Causes Control 4: 239–250.

Praud D, Bertuccio P, Bosetti C, Turati F, Ferraroni M, La Vecchia C (2014) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and gastric cancer risk in Italy. Int J Cancer 134: 2935–2941.

Prentice RL, Thomson CA, Caan B, Hubbell FA, Anderson GL, Beresford SA, Pettinger M, Lane DS, Lessin L, Yasmeen S, Singh B, Khandekar J, Shikany JM, Satterfield S, Chlebowski RT (2007) Low-fat dietary pattern and cancer incidence in the Women's Health Initiative Dietary Modification Randomized Controlled Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 99: 1534–1543.

Rose DP (1990) Dietary fiber and breast cancer. Nutr Cancer 13: 1–8.

Rossi M, Negri E, Bosetti C, Dal Maso L, Talamini R, Giacosa A, Montella M, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C (2008) Mediterranean diet in relation to body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio. Public Health Nutr 11: 214–217.

Tavani A, La Vecchia C, Gallus S, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Levi F, Negri E (2000) Red meat intake and cancer risk: a study in Italy. Int J Cancer 86: 425–428.

Tavani A, Malerba S, Pelucchi C, Dal Maso L, Zucchetto A, Serraino D, Levi F, Montella M, Franceschi S, Zambon A, La Vecchia C (2012) Dietary folates and cancer risk in a network of case-control studies. Ann Oncol 23: 2737–2742.

Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D (2003) Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med 348: 2599–2608.

Trichopoulou A, Kouris-Blazos A, Wahlqvist ML, Gnardellis C, Lagiou P, Polychronopoulos E, Vassilakou T, Lipworth L, Trichopoulos D (1995) Diet and overall survival in elderly people. BMJ 311: 1457–1460.

Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P, Kuper H, Trichopoulos D (2000) Cancer and Mediterranean dietary traditions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 9: 869–873.

Turati F, Trichopoulos D, Polesel J, Bravi F, Rossi M, Talamini R, Franceschi S, Montella M, Trichopoulou A, La Vecchia C, Lagiou P (2014) Mediterranean diet and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 60: 606–611.

World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research (2013) Continuous Update Project Report. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Endometrial Cancer Available at http://www.dietandcancerreport.org.

Xu WH, Dai Q, Xiang YB, Zhao GM, Ruan ZX, Cheng JR, Zheng W, Shu XO (2007) Nutritional factors in relation to endometrial cancer: a report from a population-based case-control study in Shanghai, China. Int J Cancer 120: 1776–1781.

Acknowledgements

The study was conducted with the contribution of the Italian Foundation for Cancer Research (FIRC), the Swiss National Science Foundation Grant 3.950-0-87 and the Swiss League against cancer (Grant OCS 1633-02-2005). We thank Mrs Ivana Garimoldi for editorial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Filomeno, M., Bosetti, C., Bidoli, E. et al. Mediterranean diet and risk of endometrial cancer: a pooled analysis of three italian case-control studies. Br J Cancer 112, 1816–1821 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.153

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.153

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Glucose metabolic reprogramming and its therapeutic potential in obesity-associated endometrial cancer

Journal of Translational Medicine (2023)

-

Scientific evidence supporting the newly developed one-health labeling tool “Med-Index”: an umbrella systematic review on health benefits of mediterranean diet principles and adherence in a planeterranean perspective

Journal of Translational Medicine (2023)

-

The Association Between Nutrition, Obesity, Inflammation, and Endometrial Cancer: A Scoping Review

Current Nutrition Reports (2022)

-

An updated systematic review and meta-analysis on adherence to mediterranean diet and risk of cancer

European Journal of Nutrition (2021)

-

Nutrition behaviour and compliance with the Mediterranean diet pyramid recommendations: an Italian survey-based study

Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity (2020)