Abstract

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) evidence has identified the metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 (GRM3) gene as a potential harbor for schizophrenia risk variants. However, previous meta-analyses have refuted the association between GRM3 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and schizophrenia risk. To reconcile these conflicting findings, we conducted the largest and most comprehensive meta-analysis of 14 SNPs in GRM3 from a total of 11 318 schizophrenia cases, 13 820 controls and 486 parent–proband trios. We found significant associations for three SNPs (rs2237562: odds ratio (OR)=1.06, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.02–1.11, P=0.017; rs13242038: OR=0.90, 95% CI=0.85–0.96, P=0.016 and rs917071: OR=0.94, 95% CI=0.91–0.97, P=0.003). Two of these SNPs (rs2237562, rs917071) were in strong-to-moderate linkage disequilibrium with the top GRM3 GWAS significant SNP (rs12704290) reported by the Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. We also found evidence for population stratification related to rs2237562 in that the ‘risk’ allele was dependent on the population under study. Our findings support the GWAS-implicated link between GRM3 genetic variation and schizophrenia risk as well as the notion that alleles conferring this risk may be population specific.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) has identified several significant genome-wide associations between genes involved in glutamatergic neurotransmission and schizophrenia.1 Among these associations, the metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 (GRM3) contained the second most significant single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (rs12704290, P=3.33 × 10−10).1 This PGC finding complements a number of previous associations between GRM3 and schizophrenia-related phenotypes, such as prefrontal activation during cognitive tasks,2 white matter integrity,3 hippocampal volume in severe obstetric complications,4 poor cognitive performance (that is, verbal fluency, digit symbol test, perseverative error processing and spatial working memory),5, 6, 7, 8, 9 antipsychotic response in first-episode schizophrenia10 and positive symptoms severity in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.5 However, two meta-analyses of GRM3 SNPs have failed to support an association with schizophrenia risk.11, 12

In the first meta-analysis, Albalushi et al.,11 studied two GRM3 SNPs (rs1468412 and rs2299225) and more recently Yang et al.,12 examined five GRM3 SNPs (rs1468412, rs274622, rs917071, rs2299225 and rs6465084). Importantly, in both these meta-analyses, the included studies primarily comprised individuals from Asian populations. This is in contrast to the PGC genome-wide association study (GWAS) that predominately included individuals of European descent, suggesting that the association between GRM3 and schizophrenia may be population specific. Furthermore, neither of the previous meta-analyses included family-based genetic association studies, which may have biased their results.

Since the publication of the most recent GRM3 meta-analysis,12 there have been three additional studies published involving 6027 (2381 schizophrenia and 3646 control) individuals,2, 6, 13 indicating a reappraisal is warranted. Thus, the aim of this study was to provide an updated and more comprehensive meta-analysis of the association between GRM3 genetic variation and schizophrenia by including both case–control and family studies as well as an exploration of potential population stratification.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A systematic search of three electronic databases: PubMed, PsycINFO and Medline (Ovid) was performed using combinations of the following keywords: ‘metabotropic glutamate receptor 3’, ‘GRM 3’, ‘mGluR3’ and ‘schizophrenia’. The search was limited to human studies published between January 2002 and December 2016. Two reviewers (SMS and MSM) independently screened the abstracts of all articles identified by the search strategy and then assessed the full-text copies of the eligible articles and extracted the data. In cases where genotype data were unavailable or incomplete, we contacted the corresponding authors and requested the data. A manual search of article bibliographies was completed to identify any non-indexed articles. The SZGene database (www.szgene.org) was also used as a resource for genotype data collection. The ‘preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols’ (PRISMA-P)14 was followed in the reporting of this meta-analysis.

Inclusion criteria and data extraction

The following inclusion criteria were used for study selection: (1) examination of GRM3 polymorphisms in schizophrenia, (2) case–control or family-based genetic association study, (3) schizophrenia diagnosis using a standard classification system (for example, DSM-IV, ICD 10 and so on)15 and (4) provided sufficient genotype or allelic data for calculation of an odds ratio (OR).

From the included studies, the following data were extracted: (a) author(s) and publication year, (b) number of cases and controls or family sample size, (c) country of origin or ethnicity of study participants, (d) diagnostic criteria used, (e) SNP reference sequence number or marker identifier, (f) the publication identification number (for example, PubMed ID) and (g) genotype counts and/or allele counts in cases and controls or family samples (transmission/non-transmission from heterozygous parents to affected offsprings). The extracted data are provided in Supplementary File 1. We also extracted haplotype data when available, but these data were not analyzed because there were no two haplotypes that appeared in three or more selected studies.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using R version 3.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The meta16 and metafor17 packages were used to conduct the meta-analyses. The OR with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used as the effect size estimator assuming an additive genetic model.

The method proposed by Kazeem and Farrall18 was used to calculate the effect size for transmission disequilibrium test studies, where the ORs were estimated from the number of transmissions versus non-transmissions of the minor or high-risk allele to schizophrenia cases from heterozygous parents. For case–control studies, ORs were calculated by contrasting the ratio of counts of the minor versus major allele or, when known, high-risk versus low-risk allele in schizophrenia cases versus healthy controls. Two-tailed P-values were reported and were indicated accordingly in the text.

All statistical tests (except for the Q-statistic) were considered statistically significant at P<0.05. Due to differences in study design and sample characteristics, considerable heterogeneity was expected between the studies. Therefore, the pooled ORs were calculated using the random-effects models with the DerSimionian–Laird (DL) estimator,19 which is based on a normal distribution. The standard error estimates were adjusted using the Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman20, 21 correction, which then calculates the corresponding 95% CIs based on the t-distribution. The Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman method generally outperforms the DL approach on type-I error rates when there is heterogeneity, and the number of studies in the meta-analysis is small.22, 23

The presence of outliers or influential studies may distort the robustness of the conclusions from the meta-analysis, and as such it is recommended that analysis of potential outlier and influential studies should be an integral part of meta-analysis.24, 25 Outliers and influential studies were identified according to the recommendations of Viechtbauer and Cheung.26 Studies with observed effects that are well separated from the rest of the data are considered outliers. Such studies were identified using studentized deleted residuals, with absolute values >1.96 indicative of outliers. An influential study leads to considerable changes to the fitted model and a range of case-deletion diagnostics adapted from linear regression can be used to identify these studies, including the DFFITS, DFBETAS and COVRATIO statistics (see Viechtbauer and Cheung26 for more information). Potential outliers and influential studies were omitted, and the analyses were then re-run to determine their influence on the pooled effect size. Removal of these studies would substantially reduce the amount of heterogeneity and increase the precision of the pooled effect size, that is, narrowing the confidence interval.

Heterogeneity in effect sizes across studies was tested using the Q-statistic (with P<0.10 indicating significant heterogeneity) and its magnitude was quantified using the I2 statistic, which is an index that describes the proportion of total variation in study effect size estimates that is due to heterogeneity and is independent of the number of studies included in the meta-analysis and the metric of effect sizes.27 As the Q-statistic has low power when the number of studies is small,28 95% prediction intervals were calculated to quantify the extent of heterogeneity in the distribution of effect sizes.29 The prediction interval is an estimation of the range within which 95% of the true effect sizes are expected to fall.

Moderator analyses for study design (case–control versus transmission disequilibrium test) and ancestry (East Asian versus European) were conducted using mixed-effects meta-analyses. For this method, studies within potential moderator groups were pooled with the random-effects model, while tests for significant differences between the groups were conducted with the fixed-effects model. The Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman adjustment was used if there were at least three studies in each group; otherwise, the unadjusted DL method was used.

Publication bias was evaluated by funnel plots and the trim-and-filled procedure,30 which yields an estimate of the effect size after publication bias has been taken into account.31 A test for funnel plot asymmetry was only performed if the number of studies was 10 or greater.32 The test proposed by Harbord et al.33 was used to quantify the bias captured by the funnel plot and tested whether it was statistically significant.

Results

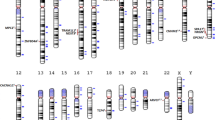

A total of 20 (17 case–control, 3 family-based) studies representing 11 318 schizophrenia cases, 13 820 controls and 486 parent–proband trios were eligible for further analysis (Supplementary Figure S1 and Table 1). Among the 48 GRM3 SNPs examined in these studies, 14 SNPs were assessed in three or more studies and were subjected to meta-analysis (Figure 1). Significant associations were not found for any of the 14 SNPs when examining all available studies (Supplementary Table S1). However, after removal of an outlier study34 the rs2237562 C allele was associated with greater schizophrenia risk (k=4, OR=1.06, 95% CI=1.02–1.11, P=0.017) (Figure 2a). In contrast, removal of influential studies35, 36 showed the C alleles for both rs13242038 (k=3, OR=0.90, 95% CI=0.85–0.96, P=0.016) and rs917071 (k=8, OR=0.94, 95% CI=0.91–0.97, P=0.003) to be associated with lower risk of the disorder (Figures 2b and c).

Schematic diagram of the GRM3 structure with locations of SNPs is examined in this meta-analysis. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) significantly associated with schizophrenia in this meta-analysis are underlined. *This SNP was excluded in this meta-analysis due to fewer than three studies but was the most significant GRM3 SNP in the PGC GWAS.1

Low to moderate heterogeneity (I2=0.0–34.6%) was present across the studies examining these three significant SNPs, although removal of outlier/influential studies reduced heterogeneity to 0% for all three SNPs (Supplementary Table S1). No evidence of moderation by study design or ancestry was detected (Supplementary Table S2 and S3).

Publication bias was evaluated for rs6465084 and rs1468412 as these were the only two SNPs with ten or more studies. The regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was statistically significant for studies examining rs1468412 (t[10]=2.35, P=0.040) (Supplementary Figure S2). After adjustment for publication bias with the trim-and-fill procedure, the odds ratio was decreased to 0.96 (95% CI=0.86, 1.07, P=0.426; the number of filled studies was 2. Given that there was a subtle reduction in the pooled odds ratio, the impact of publication bias was likely modest. For rs6465084 the regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was not statistically significant (t[8]=0.58, P=0.578) (Supplementary Figure S3).

Discussion

We found three SNPs (rs2237562, rs13242038, rs917071) in GRM3 that were significantly associated with schizophrenia. Our results differ from the two previous meta-analyses35, 36 that did not detect an association between GRM3 genetic variation and schizophrenia. However, our positive results were only apparent after removal of outlier or influential studies, a method recommended24, 25 but not employed in the previous two meta-analyses.11, 12

Importantly, our meta-analysis supports finding from the PGC GWAS, which identified GRM3 as one of 108 loci associated with schizophrenia.1 In fact, the top PGC GWAS SNP in GRM3 (rs12704290, P=1.0 × 10−10) is in moderate to strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) with two (rs2237562: D′=1.00, r2=0.485; rs917071: D′=0.64, r2=0.199) of the three significant SNPs we detected in the current meta-analysis. The association between rs2237562 and schizophrenia is particularly interesting for two reasons. First, among the 14 SNPs eligible for meta-analysis, the rs2237562 SNP had the strongest LD with the top GRM3 GWAS hit (rs12704290), which has only been examined in one case–control study6 to date. Second, in the PGC GWAS the T allele of rs2237562 was associated with schizophrenia risk (OR=1.04, P=8.3 × 10−5) while in our meta-analysis the C allele was associated with risk. One potential explanation for this discrepancy is population stratification. The PGC GWAS was predominately focused on people of European descent with people of Asian descent represented in only 3.5% (Japanese: 0.6%, Singapore: 1.2% and Chinese: 1.7%) of the studied population. Conversely, the four studies contributing to our significant meta-analysis finding were exclusively conducted in the East Asian population.6, 36, 39, 45 Notably, the two alleles for rs2237562 (T/C) occurred within similar haplotype blocks and at comparable frequencies in the European and in East Asian population (Supplementary Figures S4 and S5).

In fact, inclusion of the one outlier study,34 which was conducted in a German population and concurred with the PGC findings, eliminated the pooled effect detected among the more ancestral homogenous East Asian studies. Thus, the ‘risk’ allele for rs2237562 may be ancestry dependent, with potential implications for calculating polygenic risk scores that include this SNP within non-European populations.

It is also noteworthy that current evidence supporting an association between GRM3 genetic variation and schizophrenia susceptibility as well as cognitive and neuroimaging indices have been centered on SNPs in exon 3 and its adjacent introns.46 However, among the five SNPs we examined in this region, only the intronic rs2237562 SNP (discussed above) was supported. Yet, upstream of this region in the intron between exons I and II, we showed the C alleles for two SNPs (rs13242038 and rs917071) were associated with schizophrenia risk. Conversely, the alternative (T) allele for both SNPs was associated with lower schizophrenia risk (rs13242038: OR=0.95, P=2.7 × 10−4; rs917071: OR=0.95, P=0.056) in the PGC GWAS, suggesting again a potential population stratification effect. However, the studies contributing to the meta-analyses of these two SNPs were not ancestrally homogenous (rs13242038: 68% East Asian and 32% Caucasian; rs917071: 49% East Asian and 51% Caucasian) and moderation analysis did not detect an ancestry effect. Furthermore, the removed influential studies by Norton et al.35 for rs13242038 and Tochigi et al.36 for rs917071 were conducted in Caucasian and Asian populations, respectively. Thus, the discordance between our meta-analytical findings and those of the PGC is likely not a result of population structure. Previous research supports the PGC findings, in part, in that individuals with schizophrenia who had the rs13242038 T allele and a history of severe obstetric complications (OCs) had larger hippocampi. However, similar support for rs917071 is absent in that previous neuroimaging4 and cognitive6, 7 studies in schizophrenia have been negative to date.

The mechanisms underpinning the genetic associations between the three GRM3 SNPs and schizophrenia are still unknown. Gene expression, more specifically gene splicing, is postulated to mediate the pathophysiological effects of allelic variation.46, 47 Four alternative splice variants have been reported in the human brain: full-length GRM3 (2.8 kb), GRM3 with exon 2 deleted (GRM2Δ3, 2.2 kb), GRM3 with exon 4 deleted (GRM3Δ4, 1.8 kb) and GRM3 with exons 2 and 3 deleted (GRM3Δ2Δ3, 1.4 kb).48, 49 A previous study50 found that an exon 3 SNP (rs2228595) predicted increased transcript expression of the GRM3Δ4 splice variant that encodes a truncated receptor in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia patients, suggesting GRM3 SNPs that are in LD with rs2228595 may also affect GRM3 splicing. Interestingly, the rs2228595 is in strong LD with the PGC GWAS SNP (rs12704290: D′=1.0, r2=0.011) and our meta-analysis significant SNPs (rs2237562: D′=1.0, r2=0.170; rs917071: D′=0.757, r2=0.098), but we found no association of rs2228595 with schizophrenia in the current meta-analysis (k=5, OR=1.06, 95% CI=0.73–1.54, P=0.706). Nevertheless, there is a preliminary indication that GRM3 genetic variation may influence gene splicing, but additional research interrogating how this splicing may contribute to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia is warranted.

In conclusion, we have identified novel meta-analytically derived associations between polymorphisms within the fourth (rs2237562) and second (rs13242038, rs917071) introns of GRM3 with schizophrenia. Two of these SNPs (rs2237562, rs917071) were in strong-to-moderate LD with the top PGC SNP identified in the largest schizophrenia GWAS to date.1 We further showed that the rs2237562 allele associated with ‘risk’ for schizophrenia is likely ancestry dependant. As such, our results support the GWAS-implicated link between GRM3 genetic variation and schizophrenia risk as well as support the notion that alleles conferring this risk may be population specific. These findings provide further justification for the future study of the mechanism(s) by which GRM3 genetic variation contributes to schizophrenia risk.

References

Ripke S, Neale BM, Corvin A, Walters JT, Farh K-H, Holmans PA et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 2014; 511: 421–427.

Kinoshita A, Takizawa R, Koike S, Satomura Y, Kawasaki S, Kawakubo Y et al. Effect of metabotropic glutamate receptor-3 variants on prefrontal brain activity in schizophrenia: an imaging genetics study using multi-channel near-infrared spectroscopy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2015; 62: 14–21.

Mounce J, Luo L, Caprihan A, Liu J, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, Calhoun VD . Association of GRM3 polymorphism with white matter integrity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2014; 155: 8–14.

Haukvik UK, Saetre P, McNeil T, Bjerkan PS, Andreassen OA, Werge T et al. An exploratory model for G × E interaction on hippocampal volume in schizophrenia; obstetric complications and hypoxia-related genes. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2010; 34: 1259–1265.

Bishop JR, Miller DD, Ellingrod VL, Holman T . Association between type‐three metabotropic glutamate receptor gene (GRM3) variants and symptom presentation in treatment refractory schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol 2011; 26: 28–34.

Chang M, Sun L, Liu X, Sun W, Ji M, Wang Z et al. Evaluation of relationship between GRM3 polymorphisms and cognitive function in schizophrenia of Han Chinese. Psychiatry Res 2015; 229: 1043–1046.

Egan MF, Straub RE, Goldberg TE, Yakub I, Callicott JH, Hariri AR et al. Variation in GRM3 affects cognition, prefrontal glutamate, and risk for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 12604–12609.

Jablensky A, McGrath J, Herrman H, Castle D, Gureje O, Evans M et al. Psychotic disorders in urban areas: an overview of the study on low prevalence disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2000; 34: 221–236.

Mössner R, Schuhmacher A, Schulze-Rauschenbach S, Kühn K-U, Rujescu D, Rietschel M et al. Further evidence for a functional role of the glutamate receptor gene GRM3 in schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2008; 18: 768–772.

Bishop JR, Reilly JL, Harris MS, Patel SR, Kittles R, Badner JA et al. Pharmacogenetic associations of the type-3 metabotropic glutamate receptor (GRM3) gene with working memory and clinical symptom response to antipsychotics in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology 2015; 232: 145–154.

Albalushi T, Horiuchi Y, Ishiguro H, Koga M, Inada T, Iwata N et al. Replication study and meta‐analysis of the genetic association of GRM3 gene polymorphisms with schizophrenia in a large Japanese case‐control population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2008; 147: 392–396.

Yang X, Wang G, Wang Y, Yue X . association of metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 gene polymorphisms with schizophrenia risk: evidence from a meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2015; 11: 823–833.

O’Brien NL, Way MJ, Kandaswamy R, Fiorentino A, Sharp SI, Quadri G et al. The functional GRM3 Kozak sequence variant rs148754219 affects the risk of schizophrenia and alcohol dependence as well as bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Genet 2014; 24: 277–278.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015; 4: 1–9.

Association. D-AP Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, TX, 2013.

Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Rücker G . Meta-analysis with R. Springer: New York, NY, 2015.

Viechtbauer W . Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw 2010; 36: 1–48.

Kazeem GR, Farrall M . Integrating case-control and TDT studies. Ann Hum Genet 2005; 69: 329–335.

DerSimonian R, Laird N . Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–188.

Hartung J, Knapp G . A refined method for the meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with binary outcome. Stat Med 2001; 20: 3875–3889.

Sidik K, Jonkman JN . A comparison of heterogeneity variance estimators in combining results of studies. Stat Med 2007; 26: 1964–1981.

Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Localio R, Stack CB, Meibohm AR, Guallar E et al. Random-effects meta-analysis of inconsistent effects: a time for change. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160: 267–270.

IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF . The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 1–12.

Viechtbauer W, Cheung MWL . Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta‐analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010; 1: 112–125.

Huffcutt AI, Arthur W . Development of a new outlier statistic for meta-analytic data. J Appl Psychol 1995; 80: 327–334.

Viechtbauer W, Cheung MW . Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010; 1: 112–125.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG . Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21: 1539–1558.

Gavaghan DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ . An evaluation of homogeneity tests in meta-analyses in pain using simulations of individual patient data. Pain 2000; 85: 415–424.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ . A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 2009; 172: 137–159.

Duval S, Tweedie R . Trim and fill: a simple funnel‐plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta‐analysis. Biometrics 2000; 56: 455–463.

Higgins J, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses [journal article as teaching resource, deposited by John Flynn]. Br Med J 2003; 327: 557–560.

Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d4002.

Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA . A modified test for small‐study effects in meta‐analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med 2006; 25: 3443–3457.

Schwab SG, Plummer C, Albus M, Borrmann-Hassenbach M, Lerer B, Trixler M et al. DNA sequence variants in the metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 and risk to schizophrenia: an association study. Psychiatr Genet 2008; 18: 25–30.

Norton N, Williams HJ, Dwyer S, Ivanov D, Preece AC, Gerrish A et al. No evidence for association between polymorphisms in GRM3 and schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2005; 5: 1–6.

Tochigi M, Suga M, Ohashi J, Otowa T, Yamasue H, Kasai K et al. No association between the metabotropic glutamate receptor type 3 gene (GRM3) and schizophrenia in a Japanese population. Schizophr Res 2006; 88: 260–264.

Martí SB, Cichon S, Propping P, Nöthen M . Metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 (GRM3) gene variation is not associated with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder in the German population. Am J Med Genet 2002; 114: 46–50.

Fujii Y, Shibata H, Kikuta R, Makino C, Tani A, Hirata N et al. Positive associations of polymorphisms in the metabotropic glutamate receptor type 3 gene (GRM3) with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Genet 2003; 13: 71–76.

Chen Q, He G, Chen Q, Wu S, Xu Y, Feng G et al. A case-control study of the relationship between the metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 gene and schizophrenia in the Chinese population. Schizophr Res 2005; 73: 21–26.

Bishop JR, Wang K, Moline J, Ellingrod VL . Association analysis of the metabotropic glutamate receptor type 3 gene (GRM3) with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Genet 2007; 17: 358.

Nunokawa A, Watanabe Y, Kitamura H, Kaneko N, Arinami T, Ujike H et al. Large‐scale case‐control study of a functional polymorphism in the glutamate receptor, metabotropic 3 gene in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2008; 62: 239–240.

Nicodemus K, Marenco S, Batten A, Vakkalanka R, Egan M, Straub R et al. Serious obstetric complications interact with hypoxia-regulated/vascular-expression genes to influence schizophrenia risk. Mol Psychiatry 2008; 13: 873–877.

Betcheva ET, Mushiroda T, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Karachanak SK, Zaharieva IT et al. Case-control association study of 59 candidate genes reveals the DRD2 SNP rs6277 (C957T) as the only susceptibility factor for schizophrenia in the Bulgarian population. J Hum Genet 2009; 54: 98–107.

Jönsson EG, Saetre P, Vares M, Andreou D, Larsson K, Timm S et al. DTNBP1, NRG1, DAOA, DAO and GRM3 polymorphisms and schizophrenia: an association study. Neuropsychobiology 2009; 59: 142–150.

Jia W, Zhang R, Wu B, Dai ZX, Zhu YS, Li PP et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 is associated with heroin dependence but not depression or schizophrenia in a Chinese population. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e87247.

Harrison P, Lyon L, Sartorius L, Burnet P, Lane T . Review: the group II metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 (mGluR3, mGlu3, GRM3): expression, function and involvement in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol 2008; 22: 308–322.

Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR . Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: on the matter of their convergence. Mol Psychiatry 2005; 10: 40–68.

Sartorius LJ, Nagappan G, Lipska BK, Lu B, Sei Y, Ren‐Patterson R et al. Alternative splicing of human metabotropic glutamate receptor 3. J Neurochem 2006; 96: 1139–1148.

Moreno JL, Sealfon SC, González-Maeso J . Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors and schizophrenia. Cell Mol Life Sci 2009; 66: 3777–3785.

Sartorius LJ, Weinberger DR, Hyde TM, Harrison PJ, Kleinman JE, Lipska BK . Expression of a GRM3 splice variant is increased in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of individuals carrying a schizophrenia risk SNP. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008; 33: 2626–2634.

Acknowledgements

SMS was supported by a Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia Scholarship and the National University of Malaysia. MSM was supported by a Cooperative Research Centre for Mental Health Top-up Scholarship. CP was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Senior Principal Research Fellowship (ID: 1105825), and a Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (NARSAD) Distinguished Investigator Award. CAB was supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (ID: 1127700).

Disclaimer

None of the funding sources played any role in the study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Saini, S., Mancuso, S., Mostaid, M. et al. Meta-analysis supports GWAS-implicated link between GRM3 and schizophrenia risk. Transl Psychiatry 7, e1196 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2017.172

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2017.172

This article is cited by

-

Transcriptome Analysis and Epigenetics Regulation in the Hippocampus and the Prefrontal Cortex of VPA-Induced Rat Model

Molecular Neurobiology (2024)

-

Role of cryptic rearrangements of human chromosomes in the aetiology of schizophrenia

Journal of Genetics (2023)

-

An actualized screening of schizophrenia-associated genes

Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics (2022)

-

Neuromodulation of prefrontal cortex cognitive function in primates: the powerful roles of monoamines and acetylcholine

Neuropsychopharmacology (2022)

-

Tissue-wide cell-specific proteogenomic modeling reveals novel candidate risk genes in autism spectrum disorders

npj Systems Biology and Applications (2022)