Abstract

Pharmacological, genetic and expression studies implicate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor hypofunction in schizophrenia (SCZ). Similarly, several lines of evidence suggest that autism spectrum disorders (ASD) could be due to an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission. As part of a project aimed at exploring rare and/or de novo mutations in neurodevelopmental disorders, we have sequenced the seven genes encoding for NMDA receptor subunits (NMDARs) in a large cohort of individuals affected with SCZ or ASD (n=429 and 428, respectively), parents of these subjects and controls (n=568). Here, we identified two de novo mutations in patients with sporadic SCZ in GRIN2A and one de novo mutation in GRIN2B in a patient with ASD. Truncating mutations in GRIN2C, GRIN3A and GRIN3B were identified in both subjects and controls, but no truncating mutations were found in the GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B and GRIN2D genes, both in patients and controls, suggesting that these subunits are critical for neurodevelopment. The present results support the hypothesis that rare de novo mutations in GRIN2A or GRIN2B can be associated with cases of sporadic SCZ or ASD, just as it has recently been described for the related neurodevelopmental disease intellectual disability. The influence of genetic variants appears different, depending on NMDAR subunits. Functional compensation could occur to counteract the loss of one allele in GRIN2C and GRIN3 family genes, whereas GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B and GRIN2D appear instrumental to normal brain development and function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system and is implicated in many basic neuronal functions and central nervous system processes, in particular, learning, memory and synaptic plasticity. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR) are voltage-dependant ionotropic glutamate receptors and are tetramers containing two NR1 subunits in association with two NR2 (A, B, C or D) and/or NR3 (A or B) subunits. Many of the physiological and pharmacological properties of the NMDAR depend on the specific NR2 and NR3 subunits composition.1 Behavioral tasks that involve NMDAR include associative learning, working memory, behavioral flexibility or attention. Thus, NMDAR signaling could be a point of convergence to explain characteristic patterns of symptoms and neurocognitive deficits observed in neurodevelopmental disorders.

In schizophrenia (SCZ), dysregulation of brain glutamate transmission through NMDAR has been proposed as an etiological factor. Indeed, NMDAR antagonists (e.g., ketamine, phencyclidine) produce behavioral and cognitive deficits in normal subjects that closely mimic SCZ,2, 3, 4 and patients with anti-NR1 encephalitis display many SCZ-like symptoms and/or loss of memory.5, 6, 7 Mutant mice lacking NR1 subunit in about half of cortical interneurons early in post-natal development exhibit anxiety-like behaviors and working memory deficits, emerging at adolescence.8 In addition, NMDAR density and NMDAR subunit composition are reported abnormal in post-mortem brains of patients with SCZ.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

SCZ has been associated with genetic variants in some of the NMDAR subunit (NMDARs) genes including GRIN2A, GRIN2B and GRIN1, although contradictory results were reported (see the SCZgene database: http://www.szgene.org/).16 In addition, several genes that have been associated with increased risk for SCZ, including NRG1-erb4, serine racemase, DAO, G72 or dysbindin-1, are implicated in the modulation of NMDAR activity.17, 18, 19 Lastly, the only consistent report from independant genome-wide association studies in SCZ is the association with genetic markers in the major histocompatibility complex region,20, 21, 22 and recent evidence suggests that major histocompatibility complex region is implicated in neuronal plasticity23 and glutamatergic receptor modulation.24

Dysfunction of NMDA signaling has also been implicated in a wide range of neurological or neurodevelopmental disorders such as intellectual disability (ID),25, 26 in which it appears that specific NMDARs may have different roles in synaptic plasticity and excitotoxicity.27 In autism spectrum disorders (ASD), potentially causative mutations in NMDARs genes have been recently reported,28, 29 and a number of ASD animal models were associated with NMDA abnormalities.30, 31, 32, 33 Moreover, disruption in the balance between excitation and inhibition is a commonly proposed disease mechanism for ASD,34 and an open-label study with memantine, an antagonist of the NMDAR, significantly improved symptoms.35 Altogether, the literature suggests that NMDAR number and composition have a crucial role in neurodevelopment and cognition.

Recent studies indicate that rare and penetrant de novo mutations could account for some cases of SCZ. For examples, rare chromosomal abnormalities are more frequent in SCZ than in controls, especially rare de novo copy number variations22, 36, 37 similar to what had been reported in other neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD38 and ID.8, 39 In addition, recent reports, including ours, issued from the Synapse to Disease Project, support the implication of de novo single nucleotide mutations in ID,25, 40, 41, 42 ASD29, 41, 43 or SCZ.44, 45, 46, 47 Interestingly, among rare de novo variants reported associated with SCZ, two affect genes that may be linked to the glutamatergic synapses: SHANK3, encoding a scaffolding protein at the excitatory synapse and KIF17 encoding a synaptic motor protein, involved in the transport of NMDA receptor 2B (NR2B) to the synapse.48

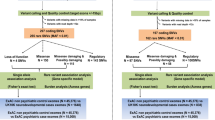

As part of the Synapse to Disease Project, in which we screened 600 synaptic genes, we screened all exons of the seven NMDARs in 571 individuals, including 429 patients with SCZ and 142 patients with ASD. We also screened all exons of the NMDARs (except for GRIN3B and GRIN1) in 283 healthy controls. Further, we screened additional cohort of ASD patients (n=286) for GRIN2B, GRIN2C and GRIN3B, and additional cohort of controls from the general population (n=285) for GRIN2C and GRIN3A. For GRIN1, we screened only this general population cohort of controls. Finally, we determined transmission of all unique variants, identified in only one individual, by sequencing parents of the carrier (292 SCZ and 404 ASD patients, with 2 parents available for screening).

We here report the identification of de novo mutations in patients with SCZ in the GRIN2A gene and in a patient with ASD in the GRIN2B gene. Also, we report the absence of truncating mutation in the GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B and GRIN2D genes in patients or controls, whereas we identified truncating mutations in the GRIN2C, GRIN3A and GRIN3B genes in patients and controls.

Methods

Subject collection

SCZ cohort

Subjects with SCZ were selected from over 1000 families ascertained for genetic studies, for which DNA samples were available. The screened cohort included 429 subjects with SCZ. We selected in priority patients with no family history of psychiatric disorders (n=188 patient) and patients for which both parents were available (n=292 patients with both parents). To ensure accurate diagnoses, all individuals were evaluated by experienced investigators (JR, LD, MOK and RJ) using the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies or the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and SCZ and multidimensional neurological, psychological, psychiatric and pharmacological assessments in the recruiting centers. Family history for psychiatric disorders was also collected using the Family Interview for Genetic Studies. All Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies and Family Interview for Genetic Studies have been reviewed by two or more psychiatrists for a final consensus diagnosis, based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mentals Disorders (DSM)-IIIR or DSM-IV at each center. For all probands, specific inclusion criteria for the present study were as follows: (1) the selected proband was definitely affected with SCZ only, not schizophreniform psychosis or bipolar disorders with psychosis; (2) in families with multiple affected individuals, we selected the most severe SCZ case with early (<18 years) or childhood onset (<12 years), and/or additional neurodevelopmental problems, such as ID, dyslexia and epilepsy, but not autistic disorder; for the childhood onset SCZ cohort, ID and epilepsy were exclusionary; (3) Family history was well documented. Finally, exclusion criteria included patients with psychotic symptoms mainly caused by alcohol, drug abuse, or other clinical diagnoses including cytogenetic abnormalities. The final panel of the samples of 429 SCZ subjects were recruited from different centers, that is, 1) 28 cases with childhood-onset SCZ and 66 with later onset SCZ from Judith L Rapoport (NIMH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Cases with childhood onset SCZ were recruited in USA nationwide and assessed as previously described.49 Individuals in this cohort known to carry the Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome (VCFS) deletion on chromosome 22q11 were excluded; 2) 38 cases from Marie-Odile Krebs (Paris, France);50 3) 84 cases from Lynn E De Lisi;51 4) 7 cases of adult onset SCZ selected from each of seven large highly consanguineous pedigrees with ⩾10 affected individuals with SCZ and schizoaffective disorders from Pakistan; 5)144 cases from Ridha Joober (Montreal, QC, Canada) including 39 cases from Tunisia;52 and 6) 62 cases from Hungary.53 The detailed description of recruitment and ascertainment strategy, diagnostic instruments and criteria have been reported by each center in their previous publications.

ASD cohort

The final panel of samples included 428 autistic patients (404 with parental DNA of both parents available). Diagnostic and selection criteria for the ASD subjects are described in detail elsewhere.54 We screened 142 autistic patients for the seven NMDAR genes, and 286 additional cases were screened for variants in GRIN2B, GRIN2C and GRIN3B. Briefly, all subjects were diagnosed using DSM-IV or DSM-IIIR criteria, and depending of the recruitment site, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule were used. In addition, the Autism Screening Questionnaire was also completed for all subjects. We excluded patients with an estimated mental age <18 months, a diagnosis of Rett syndrome or childhood disintegrative disorder, and patients with evidence of any psychiatric and neurological conditions including birth anoxia, rubella during pregnancy, fragile-X disorder, encephalitis, phenylketonuria, tuberous sclerosis, Tourette and West syndromes.

Control cohorts

Blood samples were obtained from a total of 568 control subjects. The first control series comprised healthy volunteers that were screened and selected using standardized procedures. Only individuals without any neuropsychiatric symptoms or family history of neuropsychiatric problems were included as SCZ-negative controls. These included 283 adult subjects (131 males; 152 females), 225 of whom were of European origin and 58 were non-Europeans (Tunisian). The second group of controls comprised 285 subjects from a general population control group of mainly French Canadian origin, for whom we also had parental DNA (Quebec Newborn Twin Study; 150 males, 135 females).55 We have systematically sequenced all exons of the seven NMDAR genes (except for GRIN3B and GRIN1) in the cohort of healthy volunteer controls. When rare truncating mutations were identified, we further screened all exons in additional controls from general population (Quebec Newborn Twin Study). For GRIN1, we screened only this general population cohort of controls.

DNA preparation

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood using Puregene extraction kit (Gentra System, Minneapolis, MN, USA). For certain individuals in whom blood DNA was limiting, we used DNA isolated from a lymphoblastoid cell line derived from the individual for the screen. In all cases, rare mutations were confirmed using blood-derived DNA to rule out variations having arisen during production or growth of the lymphoblastoid cell line.

Paternity testing

Paternity, maternity and unique genetic identification of each individual of all families (subject families and controls) was confirmed using 5–14 highly informative unlinked microsatellite markers as described in Gauthier et al.46

Gene screening, variation analysis and bioinformatics

In each proband, we sequenced the coding region and the splice junction of GRIN1 (chr9: 140,033,609–140,063,207, hg19 assembly), GRIN2A (chr16: 9,847,267–10,276,263), GRIN2B (chr12: 13,714,410–14,133,022), GRIN2C (chr17: 72,838,168–72,856,007), GRIN2D (chr19: 48,898,132–48,948,187), GRIN3A (chr9: 104,331,635–104,500,862). GRIN3B (chr19: 1,000,437–1,009,723) was sequenced only in patients. The detailed descriptions of the samples screened for each NMDAR gene are mentioned in Table 1. Primers were designed using the ExonPrimer program (Helmholtz Center Munich, Munich, Germany) from the UCSC genome browser (Supplementary Table 3). PCR products were sequenced at the McGill University and Genome Quebec Innovation Centre in Montreal, QC, Canada (http://gqinnovationcenter.com) on a 3730XL DNA Analyzer System (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). In each case, variations were confirmed by re-amplifying the fragment and resequencing of the samples from the proband and available parents, using reverse and forward primers. PolyPhred (version 6.11), PolySCAN (v.3.0) and Mutation Surveyor (version 3.10; Soft Genetics, State College, PA, USA) were used for mutation detection analysis. The PolyPhen (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph), SIFT (http://blocks.fhcrc.org/sift/SIFT.html), Panther (www.pantherdb.org/tools/csnpScoreForm.jsp) and SNAP (http://www.rostlab.org/services/SNAP/) programs were used to predict the overall severity of the missense mutations. In all instances, default parameters were used for each program.

Results

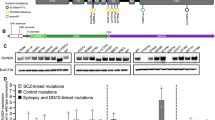

We found three de novo mutations in patients with sporadic ASD or SCZ in GRIN2A and GRIN2B (Table 2). We also identified one truncating mutations in GRIN2C, four truncating mutations in GRIN3A and recurrent truncating mutations in GRIN3B, both in patients and controls (Table 3). By contrast, we found no truncating mutations in patients or in controls in the GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B and GRIN2D genes. All three de novo mutations and truncating mutations in GRIN2C and GRIN3 were reported neither in the most recent 1000 genome release nor in hapmap.

Two de novo mutations were identified in the GRIN2A gene. The first in a patient with SCZ with no familial history of SCZ was a missense (c.2902G>A; p.A968T) located in the intracellular domain of the protein. It was not predicted as having important functional consequence based on in silico analysis (SIFT, PolyPhen and SNAP; Table 2); nevertheless, it modified an amino acid that is highly conserved in mammals. The second one was a silent mutation, c.3669C>T identified in another patient with sporadic SCZ, and was not predicted to be damaging by in silico analysis. Paternal age was 39 and maternal age was 29 for this patient. These mutations were not found in the remaining 1707 chromosomes that had been sequenced. None of these patients had a mental retardation with 11 and 12 years of education, respectively.

A missense mutation (c.2473T>G; p.L825 V) was identified in the GRIN2B gene in a patient with ASD that had no family history of neuropsychiatric disorders or ID. The mutation was confirmed by resequencing blood DNA of this patient and his parents. Paternal age was 36 and maternal age was 32 for this patient. This mutation was absent in the remaining 2279 chromosomes and was predicted by in silico analysis as relatively damaging, as it occurred in the last transmembrane domain that is highly conserved among species.

We further analyzed the prevalence of truncating mutations in our subjects. We did not identify any truncating mutations in the GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B and GRIN2D genes in 854 individuals including 429 patients with SCZ, 142 with ASD and 283 healthy controls (285 controls from general population for GRIN1). By contrast, we identified the same truncating nonsense mutation in the GRIN2C gene (c.54G>A; p.W18X) in two individuals. This mutation was first identified in an ASD patient, and this variant was transmitted from his normal father, whereas there was history of mild learning disabilities in the mother. We also found this mutation in a control from the general population.

We also identified four truncating mutations in the GRIN3A gene. Two of them were indels creating frameshift in the open-reading frame and creating nonsense codon, one in an individual from the population control cohort (c.2349delC; p.P783PfsX23) and one in a healthy control (c.2424_2425delAA; p.Q808QfsX5). The two other truncating mutations were single-nucleotide variants. The first one (c.1522C>T; p.Q508X) was identified in a patient diagnosed with catatonic SCZ and was inherited from the mother who had clinical characteristics ranging in the SCZ spectrum. The second one (c.679G>T; p.E227X) was observed in a young control from the general population. Finally, we observed frequent (10%) truncating mutations in the GRIN3B gene in the same proportion as described elsewhere in the general population.56

Overall, we identified 260 exonic variants in the seven sequenced NMDARs genes, including 159 variants that were not referenced in the dbSNP database (Build 132; Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). These variants were all confirmed manually by genotyping the proband and in the respective proband's parents, when available, to determine their inheritance. To avoid rare variants that could be linked to ethnic origin, we removed variants coming from patients with non-Caucasian ethnicity. When doing so, we did not observe either accumulation of rare variants in patients compared with controls or accumulation of more damaging variants in patients, based on in silico analysis.

Discussion

Here, we provide the first systematic study of sequence alterations in all NMDARs genes in ASD and SCZ, and report several potentially damaging and/or de novo mutations. Indeed, we identified potentially damaging de novo mutation in GRIN2A and GRIN2B associated with sporadic cases of SCZ and ASD, respectively, and truncating mutations in GRIN2C, GRIN3A and GRIN3B, whereas neither truncating nor de novo mutations were found in GRIN1 and GRIN2D.

Deep sequencing technologies have brought new insight in the genetics of neurodevelopmental disorders including SCZ. Recent reports of the literature have shown that there should be, in average, less than two de novo mutations in the coding sequence per individual and less than one de novo that would have an effect on amino acid sequence per individual.44, 57, 58

We here report on three de novo mutations, two in GRIN2A in two patients suffering from SCZ, and one in GRIN2B in a patient with autism. The mutation in GRIN2B is one of the mutations quoted in a previous paper reporting an overall rate of de novo mutation in autism or SCZ.44 In this former paper that considers the overall rate of de novo mutation, based on partial results, the mutation was unfortunately misclassified as being in a patient with SCZ, whereas it is definitely in a patient with ASD. These mutations were not inherited from unaffected parents, and the patients with de novo mutation in GRIN2A or GRIN2B did not have a predisposing or causative mutation in 600 other synaptic genes that have been sequenced, including SCZ-risk genes, such as DISC1 (data not shown). Hence, it could be hypothesized that these mutations could be associated with the pathogenesis of ASD or SCZ. This is further supported by the observation that the missense mutation in GRIN2B is predicted by in silico analysis to be relatively damaging and it occurred in the last trans-membrane domain that is highly conserved among species. In addition, one of the de novo mutations identified in the GRIN2A gene, is located in a domain that is highly conserved in mammals and vertebrates, and is known to be the target of post-translational modifications, especially phosphorylation. In particular, it has been recently proposed that abnormalities in the neuregulin 1-ErbB4 pathway, which has been implicated in SCZ and known to contribute to NMDAR hypofunction, acts through NMDARs phosphorylation by the Src tyrosine kinase.18, 19

Several studies have already screened for mutations in some NMDARs genes in neurodevelopmental diseases. Williams et al.59 screened for mutations in the GRIN1 and GRIN2 genes in patients with SCZ, but did not identify any variants that were clearly relevant to the phenotype, with only a single missense variant identified among 368 individuals (including 184 controls). Endele et al.25 screened for mutations and cytogenetic abnormalities in the GRIN2A and GRIN2B genes in patients with ID and found rare damaging de novo mutations and truncating mutations in these genes, indicating that these mutations can be pathogenic. Recently Hamdan et al.26 screened GRIN1 in patients with non-syndromic ID and identified a de novo missense and one amino acid in-frame insertion that altered the receptor's activity, the control population in this latter paper being the same as the one used in the present report. Lastly, an exome sequencing study published this year, identified several potentially causative de novo mutations on patients with ASD, one of them being in GRIN2B, within a splice site.29 As we do not provide direct evidence of a functional effect of these mutations, we cannot definitely conclude on the causal effect of de novo mutations identified in GRIN2A and GRIN2B genes. It should however be emphasized that there were no truncating mutations in at least 854 individuals (including 283 healthy volunteers) in GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B and GRIN2D, supporting the hypothesis of a high selection pressure on these genes.

In addition to de novo mutations, we identified truncating mutations in the GRIN2C, GRIN3A and GRIN3B genes in patients, population controls and/or healthy volunteers. The rate of mutations in the GRIN3B gene was in the same proportion as described in the general population, with around 10% of the individuals homozygous for truncating mutation.56 As this relatively high rate of mutation and as GRIN3B is mainly expressed in motor neurons, and thus a role in mental disorders as SCZ and ASD is unlikely, the gene was not further explored in controls.56, 60

The presence of truncating mutations in controls suggests that loss of function of these subunits leads to little or no effect. For the GRIN2C subunit, we identified the same truncating mutation in a patient with autism and in a control. Although the global functioning and learning abilities of this control appear to be in the normal range, his relatively young age at the time of his evaluation precludes from reaching firm conclusions on the effect of this truncating mutation on his future development.

On the other hand, the loss of function in one allele from the GRIN3 family genes do not appear to have dramatic consequences as truncating mutations were identified in healthy controls, suggesting some functional compensations. NMDAR containing GRIN2 subunits show large differences in their pharmacological and electophysiological properties, including glutamate affinity, modulation by glycine, sensitivity to Mg2+ and channel kinetics. As they also show a distinct spatial and chronological pattern of expression, it has been suggested that these receptors may have unique roles in brain development.1 Unlike most NMDAR that contain GRIN2 subunits, which typically require glycine and glutamate for activation, NMDAR that contain both GRIN1 and GRIN3 subunits are activated by glycine alone. When co-expressed with GRIN1 and GRIN2 subunits, GRIN3 subunits can act as negative modulators, reducing single-channel conductance and Ca2+ permeability.61 Thus, it is not surprising that rare damaging mutations could have differential effects in the GRIN2 and GRIN3 family of NMDARs.

We identified a large number of rare variants that are not in the dbSNP databases. Based on in silico analysis, these variants do not appear to be pathogenic on their own. Further, most of them are inherited from unaffected parents and some of them could be linked to the ethnic origin, as they were more frequent in the Tunisian samples. When excluding the mutations found in subjects that were not of European Caucasian origin, we did not observe any accumulation of rare or more damaging variants in patients compared with controls. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude complex gene interaction that could occur with variants in other genes.

In conclusion, our data support the hypothesis that rare de novo mutations in GRIN2A or GRIN2B could account for some cases of sporadic SCZ or autism. They also further support the implication of NMDARs in psychiatric disorders with neurodevelopmental origin. Nevertheless, a distinct pattern is observed between the different NMDARs. Truncating mutations in GRIN2C and GRIN3 were found in patients and controls, whereas no truncating mutations were found in GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B and GRIN2D. This could indicate that GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B and GRIN2D families are crucial in normal brain development and function and/or that functional compensation could occur to counteract the loss of one allele in GRIN2C and GRIN3 family genes.

References

Cull-Candy SG, Leszkiewicz DN . Role of distinct NMDA receptor subtypes at central synapses. Sci STKE 2004; 2004; re16.

Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD et al. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51: 199–214.

Krystal JH, Anand A, Moghaddam B . Effects of NMDA receptor antagonists: implications for the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59: 663–664.

Amitai N, Markou A . Disruption of performance in the five-choice serial reaction time task induced by administration of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists: relevance to cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 68: 5–16.

Vincent A, Bien CG . Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: a cause of psychiatric, seizure, and movement disorders in young adults. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 1074–1075.

Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, Rossi JE, Peng X, Lai M et al. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 1091–1098.

Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R . Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 63–74.

Belforte JE, Zsiros V, Sklar ER, Jiang Z, Yu G, Li Y et al. Postnatal NMDA receptor ablation in corticolimbic interneurons confers schizophrenia-like phenotypes. Nat Neurosci 2010; 13: 76–83.

Meador-Woodruff JH, Healy DJ . Glutamate receptor expression in schizophrenic brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2000; 31: 288–294.

Gao XM, Sakai K, Roberts RC, Conley RR, Dean B, Tamminga CA . Ionotropic glutamate receptors and expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits in subregions of human hippocampus: effects of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 1141–1149.

Ibrahim HM, Hogg Jr AJ, Healy DJ, Haroutunian V, Davis KL, Meador-Woodruff JH . Ionotropic glutamate receptor binding and subunit mRNA expression in thalamic nuclei in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 1811–1823.

Watis L, Chen SH, Chua HC, Chong SA, Sim K . Glutamatergic abnormalities of the thalamus in schizophrenia: a systematic review. J Neural Transm 2008; 115: 493–511.

Pilowsky LS, Bressan RA, Stone JM, Erlandsson K, Mulligan RS, Krystal JH et al. First in vivo evidence of an NMDA receptor deficit in medication-free schizophrenic patients. Mol Psychiatry 2006; 11: 118–119.

Kim JS, Kornhuber HH, Schmid-Burgk W, Holzmuller B . Low cerebrospinal fluid glutamate in schizophrenic patients and a new hypothesis on schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett 1980; 20: 379–382.

Akbarian S, Sucher NJ, Bradley D, Tafazzoli A, Trinh D, Hetrick WP et al. Selective alterations in gene expression for NMDA receptor subunits in prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. J Neurosci 1996; 16: 19–30.

Allen NC, Bagade S, McQueen MB, Ioannidis JP, Kavvoura FK, Khoury MJ et al. Systematic meta-analyses and field synopsis of genetic association studies in schizophrenia: the SzGene database. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 827–834.

Banerjee A, Macdonald ML, Borgmann-Winter KE, Hahn CG . Neuregulin 1-erbB4 pathway in schizophrenia: From genes to an interactome. Brain Res Bull 2010; 83: 132–139.

Hahn CG, Wang HY, Cho DS, Talbot K, Gur RE, Berrettini WH et al. Altered neuregulin 1-erbB4 signaling contributes to NMDA receptor hypofunction in schizophrenia. Nat Med 2006; 12: 824–828.

Pitcher GM, Kalia LV, Ng D, Goodfellow NM, Yee KT, Lambe EK et al. Schizophrenia susceptibility pathway neuregulin 1-ErbB4 suppresses Src upregulation of NMDA receptors. Nat Med 2011; 17: 470–478.

Shi J, Levinson DF, Duan J, Sanders AR, Zheng Y, Pe’er I et al. Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature 2009; 460: 753–757.

Stefansson H, Ophoff RA, Steinberg S, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Rujescu D et al. Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia. Nature 2009; 460: 744–747.

Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O’Donovan MC, Sullivan PF et al. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature 2009; 460: 748–752.

Shatz CJ . MHC class I: an unexpected role in neuronal plasticity. Neuron 2009; 64: 40–45.

Fourgeaud L, Davenport CM, Tyler CM, Cheng TT, Spencer MB, Boulanger LM . MHC class I modulates NMDA receptor function and AMPA receptor trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 22278–22283.

Endele S, Rosenberger G, Geider K, Popp B, Tamer C, Stefanova I et al. Mutations in GRIN2A and GRIN2B encoding regulatory subunits of NMDA receptors cause variable neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 1021–1026.

Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Araki Y, Lin DT, Yoshizawa Y, Higashi K et al. Excess of de novo deleterious mutations in genes associated with glutamatergic systems in nonsyndromic intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet 2011; 88: 306–316.

Li R, Huang FS, Abbas AK, Wigstrom H . Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in different forms of NMDA-dependent synaptic plasticity. BMC Neurosci 2007; 8: 55.

Gai X, Xie HM, Perin JC, Takahashi N, Murphy K, Wenocur AS et al. Rare structural variation of synapse and neurotransmission genes in autism. Mol Psychiatry; advance online publication, 1 March 2011 [e-pub ahead of print].

O’Roak BJ, Deriziotis P, Lee C, Vives L, Schwartz JJ, Girirajan S et al. Exome sequencing in sporadic autism spectrum disorders identifies severe de novo mutations. Nat Genet 2011; 43: 585–589.

Eadie BD, Cushman J, Kannangara TS, Fanselow MS, Christie BR . NMDA receptor hypofunction in the dentate gyrus and impaired context discrimination in adult Fmr1 knockout mice. Hippocampus, November 2010.

Maliszewska-Cyna E, Bawa D, Eubanks JH . Diminished prevalence but preserved synaptic distribution of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits in the methyl CpG binding protein 2(MeCP2)-null mouse brain. Neuroscience 2010; 168: 624–632.

Rinaldi T, Kulangara K, Antoniello K, Markram H . Elevated NMDA receptor levels and enhanced postsynaptic long-term potentiation induced by prenatal exposure to valproic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 13501–13506.

Blundell J, Blaiss CA, Etherton MR, Espinosa F, Tabuchi K, Walz C et al. Neuroligin-1 deletion results in impaired spatial memory and increased repetitive behavior. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 2115–2129.

Polleux F, Lauder JM . Toward a developmental neurobiology of autism. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2004; 10: 303–317.

Chez MG, Burton Q, Dowling T, Chang M, Khanna P, Kramer C . Memantine as adjunctive therapy in children diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorders: an observation of initial clinical response and maintenance tolerability. J Child Neurol 2007; 22: 574–579.

Ng MY, Levinson DF, Faraone SV, Suarez BK, DeLisi LE, Arinami T et al. Meta-analysis of 32 genome-wide linkage studies of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2009; 14: 774–785.

Xu B, Roos JL, Levy S, van Rensburg EJ, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M . Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with sporadic schizophrenia. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 880–885.

Pinto D, Pagnamenta AT, Klei L, Anney R, Merico D, Regan R et al. Functional impact of global rare copy number variation in autism spectrum disorders. Nature 2010; 466: 368–372.

Guilmatre A, Dubourg C, Mosca AL, Legallic S, Goldenberg A, Drouin-Garraud V et al. Recurrent rearrangements in synaptic and neurodevelopmental genes and shared biologic pathways in schizophrenia, autism, and mental retardation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66: 947–956.

Vissers LE, de Ligt J, Gilissen C, Janssen I, Steehouwer M, de Vries P et al. A de novo paradigm for mental retardation. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 1109–1112.

Hamdan FF, Daoud H, Rochefort D, Piton A, Gauthier J, Langlois M et al. De novo mutations in FOXP1 in cases with intellectual disability, autism, and language impairment. Am J Hum Genet 2010; 87: 671–678.

Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Spiegelman D, Noreau A, Yang Y, Pellerin S et al. Mutations in SYNGAP1 in autosomal nonsyndromic mental retardation. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 599–605.

Gauthier J, Siddiqui TJ, Huashan P, Yokomaku D, Hamdan FF, Champagne N et al. Truncating mutations in NRXN2 and NRXN1 in autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Hum Genet 2011; 130: 563–573.

Awadalla P, Gauthier J, Myers RA, Casals F, Hamdan FF, Griffing AR et al. Direct Measure of the De Novo Mutation Rate in Autism and Schizophrenia Cohorts. Am J Hum Genet 2010; 87: 316–324.

Tarabeux J, Champagne N, Brustein E, Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Lapointe M et al. De Novo truncating mutation in kinesin 17 associated with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 7: 649–656.

Gauthier J, Champagne N, Lafreniere RG, Xiong L, Spiegelman D, Brustein E et al. De novo mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 in patients ascertained for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 7863–7868.

Knight HM, Pickard BS, Maclean A, Malloy MP, Soares DC, McRae AF et al. A cytogenetic abnormality and rare coding variants identify ABCA13 as a candidate gene in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Am J Hum Genet 2009; 85: 833–846.

Setou M, Nakagawa T, Seog DH, Hirokawa N . Kinesin superfamily motor protein KIF17 and mLin-10 in NMDA receptor-containing vesicle transport. Science 2000; 288: 1796–1802.

Rapoport JL, Addington A, Frangou S . The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: what can very early onset cases tell us? Curr Psychiatry Rep 2005; 7: 81–82.

Gourion D, Goldberger C, Olie JP, Loo H, Krebs MO . Neurological and morphological anomalies and the genetic liability to schizophrenia: a composite phenotype. Schizophr Res 2004; 67: 23–31.

DeLisi LE, Shaw SH, Crow TJ, Shields G, Smith AB, Larach VW et al. A genome-wide scan for linkage to chromosomal regions in 382 sibling pairs with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159: 803–812.

Joober R, Rouleau GA, Lal S, Dixon M, O’Driscoll G, Palmour R et al. Neuropsychological impairments in neuroleptic-responder vs -nonresponder schizophrenic patients and healthy volunteers. Schizophr Res 2002; 53: 229–238.

Fathalli F, Rouleau GA, Xiong L, Tabbane K, Benkelfat C, Deguzman R et al. No association between the DRD3 Ser9Gly polymorphism and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2008; 98: 98–104.

Piton A, Michaud JL, Peng H, Aradhya S, Gauthier J, Mottron L et al. Mutations in the calcium-related gene IL1RAPL1 are associated with autism. Hum Mol Genet 2008; 17: 3965–3974.

Lemelin JP, Boivin M, Forget-Dubois N, Dionne G, Seguin JR, Brendgen M et al. The genetic-environmental etiology of cognitive school readiness and later academic achievement in early childhood. Child Dev 2007; 78: 1855–1869.

Niemann S, Landers JE, Churchill MJ, Hosler B, Sapp P, Speed WC et al. Motoneuron-specific NR3B gene: no association with ALS and evidence for a common null allele. Neurology 2008; 70: 666–676.

Nachman MW, Crowell SL . Estimate of the mutation rate per nucleotide in humans. Genetics 2000; 156: 297–304.

Lynch M . Rate, molecular spectrum, and consequences of human mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 961–968.

Williams NM, Bowen T, Spurlock G, Norton N, Williams HJ, Hoogendoorn B et al. Determination of the genomic structure and mutation screening in schizophrenic individuals for five subunits of the N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptor. Mol Psychiatry 2002; 7: 508–514.

Niemann S, Kanki H, Fukui Y, Takao K, Fukaya M, Hynynen MN et al. Genetic ablation of NMDA receptor subunit NR3B in mouse reveals motoneuronal and nonmotoneuronal phenotypes. Eur J Neurosci 2007; 26: 1407–1420.

Das S, Sasaki YF, Rothe T, Premkumar LS, Takasu M, Crandall JE et al. Increased NMDA current and spine density in mice lacking the NMDA receptor subunit NR3A. Nature 1998; 393: 377–381.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the families involved in this study. This work was supported by Genome Canada and Génome Québec, and received co-funding from Université de Montréal for the ‘Synapse to Disease’ (S2D) project, as well as funding from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation. JT receives a scholarship from the Université Paris Descartes (joint program Université Paris Descartes – Université de Montréal). GAR holds the Canada Research Chair in Genetics of the Nervous System and a Jeanne-et-J.-Louis-Levesque Chair for the Genetics of Brain Diseases. PD holds the Canada Research Chair in Neuroscience. JLM is a recipient of the Clinical Investigator Award of CIHR (Canadian Institutes of Health Research). The S2D team is composed of the following additional members: Isabelle Bachand, Marjolaine Chicoine, Mélanie Côté, Kathleen Daignault, Anne Desjarlais, Ousmane Diallo, Sylvia Dobrzeniecka, Joannie Duguay, Marina Drits, Philippe Jolivet, Liliane Karamera, Frédéric Kuku, Karine Lachapelle, Guy Laliberté, Sandra Laurent, Annie Levert, Meijiang Liao, Claude Marineau, Carlos Marino, Anne Noreau, Huashan Peng, Annie Raymond, Annie Reynolds, Daniel Rochefort, Judith St-Onge, Pascale Thibodeau, Kazuya Tsurudome, Yan Yang, Sophie Leroy, Narjes Bendjemaa, Katia Ossian, Mélanie Chayet and Fayçal Mouaffak. We would also like to thank Dr Chawki Benkelfat for several helpful discussions. A portion of the schizophrenia cohort was collected through the Collaborative Network for Family Study in Psychiatry (‘Réseau d’étude familiale en Psychiatry’, REFAPSY), supported by the Fondation Pierre Deniker. We also acknowledge the efforts of the members of the Génome Québec Innovation Centre Sequencing (Pierre Lepage, Sébastien Brunet and Hao Fan Yam) and Bioinformatic (Louis Létourneau and Louis Dumond Joseph) groups.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tarabeux, J., Kebir, O., Gauthier, J. et al. Rare mutations in N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors in autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry 1, e55 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.52

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.52

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Rare genetic brain disorders with overlapping neurological and psychiatric phenotypes

Nature Reviews Neurology (2024)

-

Single-locus and Haplotype Associations of GRIN2B Gene with Autism Spectrum Disorders and the Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients in Guilan, Iran

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2024)

-

Comprehensive multi-omic profiling of somatic mutations in malformations of cortical development

Nature Genetics (2023)

-

Targeting NMDA receptors in neuropsychiatric disorders by drug screening on human neurons derived from pluripotent stem cells

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

Enhancing GluN2A-type NMDA receptors impairs long-term synaptic plasticity and learning and memory

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)