Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the baseline metabolic profile (that is, metabotype) of a patient with major depressive disorder (MDD) would define how an individual will respond to treatment. Outpatients with MDD were randomly assigned to sertraline (up to 150 mg per day) (N=43) or placebo (N=46) in a double-blind 4-week trial. Baseline serum samples were profiled using the liquid chromatography electrochemical array; the output was digitized to create a ‘digital map’ of the entire measurable response for a particular sample. Response was defined as ⩾50% reduction baseline to week 4 in the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression total score. Models were built using the one-out method for cross-validation. Multivariate analyses showed that metabolic profiles partially separated responders and non-responders to sertraline or to placebo. For the sertraline models, the overall correct classification rate was 81% whereas it was 72% for the placebo models. Several pathways were implicated in separation of responders and non-responders on sertraline and on placebo including phenylalanine, tryptophan, purine and tocopherol. Dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, tocopherols and serotonin were common metabolites in separating responders and non-responders to both drug and placebo. Pretreatment metabotypes may predict which depressed patients will respond to acute treatment (4 weeks) with sertraline or placebo. Some pathways were informative for both treatments whereas other pathways were unique in predicting response to either sertraline or placebo. Metabolomics may inform the biochemical basis for the early efficacy of sertraline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Response to current therapies in treating major depression varies considerably, with ∼40% of patients not responding and 60% not remitting after an initial trial of therapy.1, 2 Further, the onset of antidepressant therapeutic action typically does not occur until after a few weeks of treatment, which delays clinicians from knowing whether an antidepressant is going to work for a particular patient. The detailed molecular mechanisms underlying variation in treatment response in depression and the genetic and biochemical basis remain unknown although numerous studies implicate the norepinephrine and serotonin (5-HT) systems.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

The placebo effect adds complexity, as 30–40% of major depressive disorder (MDD) patients respond to placebo through mechanisms that are not yet understood.11, 12, 13 Further insights into the mechanisms of response to placebo vs response to medications are needed. To date, there are no valid biomarkers of depression itself, or of response to medication or placebo. Mapping biochemical pathways that are modified in the presence of the disease alone—or upon treatment of the disease—could provide deeper insights into disease mechanisms, enable the sub-classification of disease and yield valuable biomarkers for monitoring disease progression and response to therapy. This approach could enhance the accuracy of treatment selection and minimize poly-pharmacy and trial and error treatment selection among antidepressant medications.

Metabolomics, the study of metabolism at a global ‘omics’ level, is a new, rapidly growing field with potential to impact clinical practice. The central concept is that an individual's metabolic state reflects the individual's overall health status. It involves the systematic study of the ‘metabolome’, a repertoire of small molecules present in cells, tissues and body fluids. The identities, concentrations and fluxes of these molecules represents the interactions from gene sequence to gene expression, protein expression and the total cellular environment, an ‘environment’ that—in the clinical setting—includes drug exposure.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

Metabolomics typically utilizes technologies that aim at simultaneously quantifying thousands of small molecules in a biological sample. This analytical capability can then be joined to sophisticated mathematical analyses to identify metabolic profiles, which could provide valuable data to design (1) prognostic, diagnostic and surrogate markers for disease state; (2) the ability to subclassify disease; (3) biomarkers of drug response phenotypes leading to patient stratification (pharmaco-metabolomics); and (4) information about disease mechanisms. Sophisticated metabolomic analytical platforms, statistics and bioinformatics tools have recently been developed to enable metabolic characterization of initial signatures for several diseases including depression,20, 21, 22 motor neuron disease,23 Parkinson's disease,24 cocaine and opiate addiction,25, 26 schizophrenia,27, 28, 29 rat models of caloric restriction.16

This study obtained metabolic profiles of depressed outpatients using electrochemistry-based metabolomics and considered the following questions:

-

1)

Can baseline metabolic profiles distinguish between patients who do and do not respond to 4-week treatment with sertraline?

-

2)

Can baseline metabolic profiles distinguish between patients who do and do not respond to 4 weeks of treatment with placebo?

-

3)

Can baseline metabolic profiles differentiate patients who respond on sertraline from those who respond on placebo?

Patients and methods

Study design

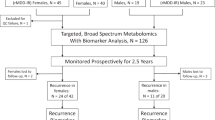

The 89 patients in this report were a subset of the 165 patients who entered a randomized, double-blind, flexible dosing, placebo-controlled study performed at 12 clinical sites. In the larger study, patients were randomized to treatment (oral administration) with either sertraline or placebo at a ratio of 1:1. Sertraline dosing was started with 50 mg per day at baseline (week 0), with dose increased up to 100 mg per day at week 1 and up to 150 mg per day at week 2, as seen needed by the treating clinician. These 89 patients were older (42 yrs vs 33 yrs, P<0.0001) and included more females (69 vs 57%) than the 76 patients for which we did not have adequate data to include in the analysis. Baseline HRS-D17 scores were similar for the two groups (the mean (s.d.) baseline HRS-D17 for subjects within this analysis was 24.8 (2.9) vs 24.6 (2.8) for the remainder of the trial subjects), indicating no significant difference in terms of pre-treatment severity of disease. Subjects selected for this study were those with serum samples and HRS-D17 scores available at baseline and at 4 weeks (±1 week) after treatment.

Patients

Study participants were outpatients, 18–65 years of age, from various sites across the United States. Patients had a primary diagnosis of MDD by DSM-IV criteria, with symptoms of depression present for at least 1 month before screening, and a total baseline score >22 on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD17)30 at screening. A complete description of the inclusion and exclusion used in this study can be found in Supplementary Table S1. The study protocol was developed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent. The study was sponsored and monitored by Pfizer. Each site's IRB approved and oversaw the study.

Assessments

Measures were gathered at baseline, week 1 and week 4 of treatment at the clinic visits. The primary outcome measure was the HRSD17,30 used to assess depressive symptom severity. Assessments of the HRSD17 were obtained at baseline and at week 4. The HRSD score was modeled as dichotomous response variable. A patient was considered a responder to therapy if they showed a ⩾50% reduction if HRSD scores from baseline to 4 weeks. This study included the collection of serum samples drawn from the subset of 89 patients at baseline and week 4. The samples from these 89 patients were profiled using the liquid chromatography electrochemical array (LCECA) platform described below.

Metabolomic profiling

Analysis method

Samples were analyzed using a long gradient LCECA method that resolves ca.1500–2000 compounds in levels to ca. 500 pg per ml.31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 The method is specific for compounds that will undergo electrochemical oxidation or reduction, and includes multiple compounds from the tyrosine, tryptophan, sulfur amino acid and purine pathways, and markers of oxidative stress and protection. The method employs a 120-min gradient from 0% organic modifier with an ion-pairing agent (pentane sulfonic acid) to a highly organic mobile phase with 80/10/10% methanol/isopropanol/acetonitrile. An array of 16 serial coulometric electrochemical detectors is set at incremental potentials from 0–900 mV, responding to oxidizable compounds such as tocopherol in lower potential sensors and higher oxidation potential compounds such as hypoxanthine in the higher potential channels.

Analysis sequence and data output

At the time of preparation, a pool was created from small aliquots of each sample in the study, which was then treated identically to a sample. All assays were run in sequences that included mixed standard, five samples, pool, five samples, mixed standard, and so on. Run orders of all samples in this study were randomized. The sequences minimized possible analytical artifacts during further data processing. Data were time normalized to a pool at the midpoint of the study, aligning major peaks to 0.5 s and minor peaks to 0.5–2 s.

For the purpose of this study, the data were exported in digital format (digital maps), which allows to capture all analytical information for the following data analysis and to avoid possible artifacts introduced by peak-finding algorithms. In this study, resolution was set at 1.5 s and the number of data points (variables, defined as the signal at a given time on a given channel) obtained from one sample, using our current LCECA platform, was 65 000. Values for each sample were then adjusted by averaging between pools to compensate for any response drift over the study period. All rows for which the maximum value was below the noise level of the system were eliminated from subsequent data analysis, leaving ∼14 000 variables. It is important to note that the number of variables in digital maps is not equivalent to the number of analytes, because an individual analyte is represented by more than one variable. Depending on the concentration of analyte and on its separation across EC array, the number of variables characterizing an analyte could be between 10 and 100. Following finding the variables differentiating the groups, the variables were sorted by retention time and channel. This step allowed isolation of ‘peak clusters’ (that is, all digital map variables characterizing one specific analyte), which, in turn, provides an identification of specific markers. Then the most significant variables in the digital maps were used to identify the location of the actual marker peaks within the chromatograms.

Data analysis

Analysis of the digital maps

Before analysis, a relative s.d. was calculated for each variable in order to identify possible outliers.40 Variables with a relative s.d. value >120% were taken out of the data set. A high relative s.d. often reflects sporadic use of other drugs. Thus, these variables were removed primarily to avoid artifacts from differential drug use in responders or non-responders. The remaining variables were log 2 transformed.

The primary objective of the modeling was to determine whether the baseline metabolomic profile could predict responder versus non-responder status at week 4, based on percent of HRSD17 score change from Baseline. Digital maps were used to construct partial least square-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) models for the 43 patients in the sertraline group and the 46 patients in the placebo group. We used the variable influence on the projection (VIP) parameter to identify variables making the most significant contribution in discriminating between responders and non-responders on sertraline therapy and placebo in the PLS-DA models. VIP is a weighted sum of squares of the PLS weight, which indicates the importance of the variable to the whole model. Higher scores reflect a greater contribution to the separation of the groups, in this case responders and non-responders to sertraline or placebo. Cross-validation of these models was performed by omitting the data from one patient before model constructions.40 After the one-out models were built the data sets were reconstructed, including only the variables with VIP values >0.7. These data sets contained ∼4000 variables representing roughly 30 discrete compounds. The one-out models were rebuilt with the reconstructed data set and used to classify the omitted patients as a responder or non-responder. This procedure was repeated until every subject had been kept out once.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sertraline and placebo groups did not differ significantly in age (44±11.4 years vs 40±12.7 years, P=0.12), body mass index (27.76±5.76 vs 29.37±6.45, P=0.22), gender (29/43 (69%) female vs 32/46 (70%) female, P=0.83) or race (34/43 (79%) white vs 34/46 (74%) white, P=0.57). The response rate was slightly higher for sertraline than for placebo, but this difference was not statistically significant (25/43 (58%) vs 18/46 (39%) responders, χ2(1)=1.39, P=0.24).

Metabolomic profiles at baseline partially separate responders and non-reponders treated with sertraline

We used an electrochemistry based metabolomics platform (LCECA) to profile samples at baseline and post treatment with sertraline or placebo. This platform enables quantification of over a thousand compounds that will undergo electrochemical oxidation or reduction, and is particularly suitable for studying neurotransmitter pathways tryptophan and tyrosine as well as sulfur amino acid and purine pathways, and markers of oxidative stress and protection.31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 A list of metabolites with known chemical structure that were quantitatively measured using this platform is presented in Table 1. The chemical structure of many metabolites detected by this highly sensitive platform currently remains unknown.

The variables from the digital maps were used to construct PLS-DA models for the 43 patients in the sertraline group (see methods section). Figure 1a shows the separation of responders (⩾50% decrease in HRSD17 scores at week 4) and non-responders (<50% decrease in HRSD17 scores at week 4) to sertraline.

We used the VIP parameter to identify variables that have the most significant contribution in discriminating between responders and non-responders on sertraline therapy in the PLS-DA model (See Table 2). Some of the metabolites that contribute to separation have known chemical structure and included dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC, dopamine pathway), 4-hydroxyphenyllactic acid (4-HPLA, phenylalanine pathway), serotonin (5-HT, tryptophan pathway) and gamma tocopherol (vitamin E pathway). There were several compounds of unknown structure that emerged as significant in contributing to the separation of responders and non-responders. Many of these had VIP values greater than the one associated with DOPAC, which had the highest VIP value of the known compounds.

Cross-validation of these models was performed by omitting the data from one patient during the PLS-DA. After this model was built the data set was trimmed, including only the variables with a VIP of greater than 0.7. The trimmed data sets contained ∼4000 variables representing about 30 discrete compounds. The model was rebuilt with the trimmed data set and used to classify the omitted patient as a responder or non-responder. This procedure was repeated until every subject had been kept out once. Using this one-out method we were able to correctly classify 21 of 25 (84%) responders and 14 of 18 (74%) non-responders with an overall classification rate of about 81%.

Metabolic profiles at baseline partially separate responders and non-reponders treated with placebo

PLS-DA analysis of the 46 patients in the placebo arm show partial separation of responders and non-responders using binary analysis described above (Figure 1b). Hypoxanthine, xanthine and uric acid (purine pathway); 5-methoxytryptophol (5-MTPOL), serotonin (5-HT), 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-OHKY) and 5-hydroxyindoleactic acid (tryptophan pathway); DOPAC (dopamine pathway); cysteine (sulfur amino acid, one carbon metabolism); and several tocopherols (vitiman E) contributed to the separation of the responders and non-responders on placebo (see Table 2). The highest known VIPs were from compounds that are from the purine pathway (that is, hypoxanthine and uric acid) indicating that this biochemical pathway is of particular importance. It is also important to note that there were several unknown compounds that were among the most influential variables in this model. Cross-validation of these models using the ‘one out’ method described above enabled correct classification of 8 of 19 (42%) of the responders and 25 of 27 (93%) of the non-responders with an overall classification rate of 72%.

Discussion

It is important to define the metabotype of patients who will not respond to treatment with a particular SSRI, as it can reduce the trial and error approach to treatment and help with selection of an efficacious drug for each patient. Defining who might respond on placebo is also of great importance as those who are very likely to respond on placebo could be excluded from clinical trials to increase the chances for seeing a drug-specific effect. This may also reduce patient's exposure to drugs they might not need. In antidepressant trials, placebo response is typically high and tends to obscure efficacy signals of drugs, while introducing heterogeneity in the observed endpoints such as the HRSD17. Any new tool to reduce this unwanted data variability, based on well-demonstrated data, would greatly benefit clinical trials as well as clinical practice.

Analysis of metabolic profiles at baseline using digital maps enabled separation of responders and non-responders on sertraline, and between responders and non-responders on placebo. This approach identified several compounds that contributed to separation of responders and non-responders on sertraline in the PLS-DA model. These included DOPAC, 4-HPLA, 5-HT and gamma tocopherol. In the placebo group we note several metabolites contributed to separation of responders and non-responders. These include: hypoxanthine, xanthine and uric acid (purine pathway); 5-MTPOL, 5-HT, 3-OHKY and 5-hydroxyindoleactic acid (tryptophan pathway); DOPAC (tyrosine), cysteine and tocopherols (vitamin E).

Analysis of sertraline and placebo models shows that DOPAC, gamma tocopherol, and serotonin significantly contributed to the separation of responders and non-responders, though the relative strength of DOPAC was different in the two models. There were a number of known compounds that contributed to separation of responders and non-responders that appeared to be unique to either sertraline or placebo. Examples include the importance of purines and 5-MTPOL in response to placebo, but not to sertraline and the role of 4-HPLA in response to sertraline, but not to placebo. Thus, it appears that the metabotype of responders to sertraline only partially overlaps with that of responders to placebo.

Models based on variables selected from the total output of the LCECA platform enabled partial classification of responders and non-responders on sertraline based on percent change in HRSD17 score from baseline to week 4. With this relatively small sample size, we were able to classify 21 of 25 (84%) responders and 14 of 18 (78%) non-responders on sertraline with an overall classification rate of about 81%. In the placebo-treated group, we were able to predict better the non-responders 25 of 27 (93%) but prediction of responders was not possible in this pilot study (8 of 19 or 42% of the responders). The overall classification rate in placebo was 72%. This suggests that biological response to place could be more complex, as reflected by metabolomic profiles, compared with the response to drug.

It is interesting to note that 5-MTPOL is a methylated product within the methoxyindole pathway in the pineal gland.41, 42, 43 5-MTPOL is produced from serotonin through a series of steps involving monoamine oxidase, aldehyde reductase and hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase. 5-MTPOL has important functions that parallel melatonin, another methylated product of serotonin produced in pineal gland. Both molecules are implicated in sleep architecture, circadian rhythm and hormonal axis regulation, among other important functions that are often altered in depressed patients. Full analysis of this pathway is underway. 4-HPLA belongs to the phenyl alanine pathway and is interconnected with the tyrosine pathway and catecholamine production.

Many of the most influential variables discriminating between responders and non-responders to sertraline and responders and non-responders to placebo were of unknown structure. If these associations are confirmed in larger studies it would be of importance to focus on elucidating the chemical structure of those metabolites as a next step towards a more complete understanding of the biochemistry underpinning response variation to sertraline and placebo. This will entail a larger initiative beyond the scope of the current work.

Studies with larger sample sizes will be needed to better predict who will and will not respond to either sertraline or placebo at week 4 and to determine whether they have a common metabolomic profile. This might enable the pre-selection of these patients for a different treatment strategy. Any tools that can help a clinician define early on if a patient is not going to respond to an SSRI would be very useful and can minimize the poly-pharmacy approach in depression treatment.

Our findings suggest that response to sertraline and response on placebo are a function of the underlying unique metabotype of the patient at baseline. This inherent metabolomic fingerprint captures a metabolic state as regulated by genome, proteome and environment interactions. This holds promise for enabling sub-classification of depression states and improving clinical decisions from an initial set of biochemical analyses before prescription of a given therapy, much like tumor genotyping for treatment selection.

It is important to note that this analysis was performed on a subset of MDD patients and presented inherent limitations. We have focused on an early time point of response and a longitudinal study is needed where one would evaluate earlier and later time points up to 12 weeks. Our interest in the earlier time points was based on our desire to develop biomarkers of early response, or no response. Larger studies would be needed to better define effects of gender and ethnic background on metabolic signatures of response and to enable sub stratification of depression. The presence of outliers might represent subtypes of MDD that will require larger sample sizes to more fully characterize. In an ongoing study of 1200 MDD patients treated with escitalopram citalopram at the Mayo Clinic, metabolomic and genetic data are being used to better define subtypes of depression and metabolic signatures of early response, late response or no response. An additional limitation to our study is that the LCECA platform captures information on only redox active compounds in the tyrosine, tryptophan, purine and sulfur amino acid pathways and several markers of vitamin status and oxidative processes. The integration of data from lipidomics and mass spectrometry-based metabolomics platforms in future studies will be necessary to yield additional response predictive power.

In summary, we have shown that the baseline metabolomic profile or ‘metabotype’ of an MDD patient, as indexed by an electrochemistry metabolomics platform total output (digital map), could help classify patients as responders or non-responders to sertraline or to placebo. It suggests that metabolomics and metabolic profiles of patients could be valuable in helping to guide therapeutic choices, thus reducing trial and error in matching the right drug with the right patient. Such findings have the potential to contribute to personalizing therapeutic treatment for patients with a diagnosis of MDD. Confirmation of these results with samples from an unrelated clinical trial of similar design would greatly enhance the impact of these early reported findings. These results provide a powerful stepping stone into a thorough metabolite identification campaign that will highlight the pathways involved in both response mechanisms, and hopefully lead to biomarker discovery usable in clinical practice and clinical trial design. Efforts are already ongoing to collect samples from independent trials to confirm the present findings. Although this study focused on the use of an electrochemistry platform and a specific area of biochemistry, future studies using complementary platforms will enable us to define further the biochemical pathways contributing to response variation. The ultimate goal would be to reduce the complexity of a digital map and identify a subset of known metabolites that are easily measured in a clinical setting. In conclusion, this study supports the feasibility of using metabolomics as a tool for understanding individual variation in response to pharmacotherapy for MDD and hence means to sub-classify patients with depression.

References

Trivedi MH . Major depressive disorder: remission of associated symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67 (Suppl 6): 27–32.

Sullivan GM, Oquendo MA, Simpson N, Van Heertum RL, Mann JJ, Parsey RV . Brain serotonin 1A receptor binding in major depression is related to psychic and somatic anxiety. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58: 947–954.

Insel TR, Wang PS . The STAR*D trial: revealing the need for better treatments. Psychiatr Serv 2009; 60: 1466–1467.

Ressler KH, Nemeroff CB . Role of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems in the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety 2000; 12 (Suppl 1): 2–19.

Malhi GS, Parker GB, Greenwood J . Structural and functional models of depression: from sub-types to substrates. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005; 111: 94–105.

Leonard BE . Psychopathology of depression. Drugs Today 2007; 43: 705–716.

Katz MM, Bowden CL, Frazer A . Rethinking depression and the actions of antidepressants: uncovering the links between the neural and behavioral elements. J Affect Disord 2010; 120: 16–23.

Nutt DJ . The role of dopamine and norepinephrine in depression and antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67 (Suppl 6): 3–8.

Nutt DJ . Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69 (Suppl E1): 4–7.

Charney DS . Monoamine dysfunction and the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59 (Suppl 14): 11–14.

Brunoni AR, Fraguas R, Fregni F . Pharmacological and combined interventions for the acute depressive episode: focus on efficacy and tolerability. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2009; 5: 897–910.

Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M . Placebo response in studies of major depression: variable, substantial, and growing. JAMA 2002; 287: 1840–1847.

Kirsch I . Challenging received wisdom: antidepressant and the placebo effect. Mcgill J Med 2008; 11: 219–222.

Kaddurah-Daouk R, Kristal BS, Weinshilboum RM . Metabolomics: a global biochemical approach to drug response and disease. Annu Rev Pharmicol Toxicol 2008; 48: 653–683.

Kadddurah-Daouk R, Krishnan KR . Metabolomics: a global biochemical approach to the study of central nervous system diseases. Neruopsychopharmacology 2009; 34: 173–186.

Kristal BS, Shurubor Yl, Kaddurah-Daouk R, Matson WR . Metabolomics in the study of aging and caloric restriction. Methods Mol Biol 2007; 371: 393–409.

Holmes E, Wilson ID, Nicholson JK . Metabolic phenotyping in health and disease. Cell 2008; 134: 714–717.

Han X, Yang J, Yang K, Zhao Z, Abendschein DR, Gross RW . Alterations in myocardial cardiolipin content and composition occur at the very earliest stages of diabetes: A shotgun lipidomics study. Biochemistry 2007; 46: 6417–6428.

Han X . Potential mechanisms contributing to the sulfatide depletion at the earliest clinically recognizable stage of Alzheimer's disease: A tale of shotgun lipidomics. J Neurochem 2007; 103: 171–179.

Paige LA, Mitchell MW, Krishnan KR, Kaddurah-Daouk R, Steffens DC . A preliminary metabolomics analysis of older adults with and without depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007; 22: 418–423.

Steffens DC, Jiang W, Krishnan KR, Karoly ED, Mitchell MW, O'Connor CM et al. Metabolomic differences in heart failure patients with and without major depression. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2010; 23: 136–146.

Ji Y, Zhu H, Jenkins GD, Biernacka J, Snyder K, Drews M et al. Glycine and a glycine dehydrogenase (GLDC) SNP as citalopram/escitalopram response biomarkers in depression: pharmacometabolomics-informed pharmacogenomics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011; 89: 97–104.

Rozen S, Cudkowicz ME, Bogdanov M, Matson WR, Kristal BS, Beecher C et al. Metabolomic analysis and signatures in motor neuron disease. Metabolomics 2005; 1: 101–108.

Bogdanov M, Matson WR, Wang L, Matson T, Saunders-Pullman R, Bressman SS et al. Metabolomic profiling to develop blood biomarkers for Parkinson's disease. Brain 2008; 131 (Part 2): 389–396.

Patkar AA, Rozen S, Mannelli P Matson W, Pae CU, Krishnan KR, Kaddurah-Daouk R . Alterations in tryptophan and purine metabolism in cocaine addiction: a metabolomics study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009; 206: 479–489.

Mannelli P, Patkar A, Rozen S, Matson W, Krishnan R, Kaddurah-Daouk R . Opioid use affects antioxidant activity and purine metabolism: preliminary results. Hum Psychopharmacol 2009; 24: 479–489.

Kaddurah-Daouk R, McEvoy J, Baillie RA, Lee D, Yao JK, Doraiswamy PM et al. Metabolomic mapping of atypical antipsychotic effects in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2007; 12: 934–935.

Yao JK, Dougherty Jr GG, Reddy RD, Keshavan MS, Montrose DM, Matson WR et al. Altered interactions of tryptophan metabolites in first-episode neuroleptic-naïve patients with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2009; 15: 938–953.

Yao JK, Dougherty Jr GG, Reddy RD, Keshavan MS, Montrose DM, Matson WR et al. Homeostatic imbalance of purine catabolism in first-episode neutroleptic-naïve patients with schizophrenia. PLoS One 2010; 5: e9508.

Hamilton M . A Rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23: 56–61.

Beal MF, Swartz KJ, Isacson O . Developmental changes in brain kynurenic acid concentrations. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 1992; 68: 136–139.

Shi H, Vigneau-Callahan KE, Shestopalov AI, Milbury PE, Matson WR, Kristal BS . Characterization of diet-dependent metabolic serotypes: Proof of principle in female and male rats. J. Nutr 2002; 132: 1031–1038.

Paolucci U, Vigneau-Callahan KE, Shi H, Matson WR, Kristal BS . Development of biomarkers based on diet-dependent metabolic serotypes: characteristics of component-based models of metabolic serotypes. OMICS 2004; 8: 221–238.

Paolucci U, Vigneau-Callahan KE, Shi H, Matson WR, Kristal BS . Development of biomarkers based on diet-dependent metabolic serotypes: concerns and approaches for cohort and gender issues in serum metabolome studies. OMICS 2004; 8: 209–220.

Shi H, Paolucci U, Vigneau-Callahan KE, Milbury PE, Matson WR, Kristal BS . Development of biomarkers based on diet-dependent metabolic serotypes: practical issues in development of expert system-based classification models in metabolomic studies. OMICS 2004; 8: 197–208.

Volicer L, Langlais PJ, Matson WR, Mark KA, Gamache PH . Serotoninergic system in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Abnormal forms of 5-hydroxytryptophan and serotonin in cerebrospinal fluid. Arch Neurol 1985; 42: 1158–1161.

Godefroy F, Matson WR, Gamache PH, Weil-Fugazza J . Simultaneous measurements of tryptophan and its metabolites, kynurenine and serotonin, in the superficial layers of the spinal dorsal horn. A study in normaland arthritic rats. Brain Res 1990; 526: 169–172.

Beal MF, Matson WR, Swartz KJ, Gamache PH, Bird ED . Kynurenine pathway measurements in Huntington′s disease striatum: evidence for reduced formation of kynurenic acid. J Neurochem 1990; 55: 1327–1339.

Loeffler DA, LeWitt PA, Juneau PL, Camp DM, DeMaggio AJ, Havaich MK et al. Influence of repeated levodopa administration on rabbit striatal serotonin metabolism, and comparison between striatal and CSF alterations. Neurochem Res 1998; 23: 1521–1525.

Erikson L, Johaannson E, Kettanah-Wold N, Wold S . Multi- and megavariate data analysis. Umetyrics AB, Malmo: Sweden, 2001.

Wurtman RJ, Axelrod J . The pineal gland. Sci Am 1965; 213: 50–60.

Mullen PE, Leone RM, Hooper J, Smith I, Silman RE, Finnie M et al. Pineal 5-methoxy tryptophol in man. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1979; 2: 117–126.

Reiter RJ . The pineal gland: an intermediary between the environment and the endocrine system. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1983; 8: 31–40.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dorothy Peters for her assistance in preparation of this manuscript and also acknowledge the editorial support of Jon Kilner (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). This work was done with funding from Pfizer corporation and from NIGMS grant GM078233, ‘The Metabolomics Research Network for Drug Response Phenotype’ (RKD, WM, SB, EC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr Kaddurah-Daouk is an equity holder in Metabolon, a biotechnology company in the metabolomics domain, and also an inventor on patents in the metabolomics field. She has received funding or consultancy fees for BMS, Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Lundbeck. Dr Ranga Krishnan has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bristol-Myer Squibb, CeNeRx, Corcept, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Organon, Pfizer, Sepracor and Wyeth. Additionally, he is an inventor on patents in the metabolomics field. Dr Wayne Matson is an inventor on patents in the metabolomics field. A John Rush has received consulting fees from Advanced Neuromodulation Systems, Best Practice Project Management, Otsuka, University of Michigan and Brain Resource; consultant/speaker fees from Forest Pharmaceuticals; consultant fees and is a stockholder of Pfizer; other royalties from Guilford Publications, Healthcare Technology Systems and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and research support from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kaddurah-Daouk, R., Boyle, S., Matson, W. et al. Pretreatment metabotype as a predictor of response to sertraline or placebo in depressed outpatients: a proof of concept. Transl Psychiatry 1, e26 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.22

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.22

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multi-omics reveal microbial determinants impacting the treatment outcome of antidepressants in major depressive disorder

Microbiome (2023)

-

Predicting treatment outcome in depression: an introduction into current concepts and challenges

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2023)

-

Association between cord blood metabolites in tryptophan pathway and childhood risk of autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

A metabolome-wide association study in the general population reveals decreased levels of serum laurylcarnitine in people with depression

Molecular Psychiatry (2021)

-

Metabolomic signatures associated with depression and predictors of antidepressant response in humans: A CAN-BIND-1 report

Communications Biology (2021)