Abstract

Iron chalcogenide superconductors FeSe1−xTe x are important materials for investigating the relation be-tween the superconductivity and the orbital and/or electronic nematic order, because the end member material FeSe exhibits a structural transition without a magnetic phase transition. However, the phase separation occurs in the region of 0.1 ≤ x ≤ 0.4 for bulk samples, and it prevents the complete understanding of this system. Here, we report the successful fabrication of epitaxial thin films of FeSe1−xTe x with 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.7, which includes the phase-separation region, on LaAlO3 substrates via pulsed laser deposition. In the temperature dependences of differential resistivity for these films with 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.3, the dip- or peak- anomalies, which are well-known to be originated from the structural transition in FeSebulk samples, are observed at the characteristic temperatures, T*. The doping-temperature (x–T) phase diagram of FeSe1−xTex films clearly shows that T* decreases with increasing x, and that Tc suddenly changes at a certain Te content where T* disappears, which turns out to be commonly observed for both films on LaAlO3 and CaF2. These indicate the importance of controlling the structural transition to achieve high Tc in iron chalcogenides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of iron-based superconductors has attracted much attention to fundamental studies and applications1. The iron-chalcogenide superconductors, FeSe2 and FeSe1−xTex3 have the simplest crystal structure among the iron-based superconductors, composed of conducting planes alone. The superconducting transition temperature, Tc, of FeSe is 8 K, and the partial substitution of Te for Se raises Tc up to ∼14 K. These values are rather low compared with other iron-based superconductors. However, the remarkable thing is the strong pressure dependence of Tc; Tc of FeSe reaches ∼30 K under high pressure4,5. This fact suggests that FeSe thin films can have Tc values higher than those of bulk single crystals when in-plane strain is induced in the films. Indeed, FeSe films on CaF2 substrates, whose in-plane lattice parameters are much smaller than that of an FeSe bulk sample, show superconductivity with Tc of 15 K6,7,8, which are almost twice as large as that of an FeSe bulk sample. In addition, monolayer FeSe films on SrTiO3 substrates exhibit very high Tc9. Although it is under debate whether both of these enhancements of Tc have the same origin or not, these results demonstrate that FeSe has a potential for a high Tc superconductor.

FeSe is also a unique material in iron-based superconductors in the sense that it exhibits a structural transition from tetragonal to orthorhombic at ∼90 K without a magnetic phase transition. The orbital-ordered and/or nematically-ordered state is observed below the structural transition temperature10,11. This is in contrast to other iron-based superconductors where a structural and a magnetic phase transition occur almost simultaneously. Therefore, iron-chalcogenide superconductors FeSe and Te-substituted Fese1−xTex are important materials for investigating the relation between the superconductivity and the orbital and/or electronic nematic order. However, it is known that single-phase FeS1−xTex bulk samples with 0.1 ≤ x ≤ 0.4 are not available because of a phase separation3, and this fact hindered the complete understanding of FeSe1−xTex. Recently, we succeeded in obtaining FeSe1−xTex thin films on CaF2 substrates with these compositions by a pulsed laser deposition (PLD) method12. Tc of these films reaches 23 K at x = 0.2, and a sudden suppression of Tc is observed between x = 0.1–0.2. On the other hand, in the film preparation of FeSe1−xTex with whole range of x on MgO substrate13, only films with x = 0.1–0.4 have a very broad peak in the x-ray diffraction patterns, indicating the existence of the phase separation. Hence, it is of great interest whether the suppression of phase separation is realized only in the case of CaF2 substrate or not.

Here, we report the successful fabrication of epitaxial thin films of FeSe1−xTex with x = 0–0.7 on LaAlO3 (LAO) substrate by the PLD method. The highest Tc of the films on LAO substrates reaches 19 K, which is also higher than that of bulk samples. The dip- or peak- behaviors, which are well-known to be originated from the structural transition in FeSe bulk samples14,15,16,17,18,19, are observed in the temperature dependences of differential resistivity for those films with 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.3. More importantly, in the doping-temperature (x–T) phase diagram of FeSe1−xTex thin films on LaAlO3, we observe a systematic decrease of its anomaly temperature in the resistivity data with increasing x and a sudden increase in Tc at x = 0.4 where the dip- or peak- anomaly disappears. These findings demonstrate that the sudden changes in Tc which are commonly observed for both films on LaAlO3 and CaF2 should be closely related to a structural transition regardless of the substrate materials.

Results and Discussion

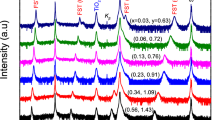

Figure 1a shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the FeSe1−xTex thin films with x = 0–0.5 fabricated on LAO substrates. Here and hereafter, the Te content x of the film represents the nominal Te composition of the polycrystalline target. These films show only the 00l reflections of the tetragonal PbO structure, indicating that the films are well-oriented along the c-axis. Figure 1b and c show the enlarged XRD patterns around the 001 and 004 peaks. The 2θ values of these peaks decrease with increasing x systematically, which is consistent with the dependence of c on x in FeSe1−xTex. Here, it should be noted that there are neither splits nor broadening of the peaks even in the patterns of films with x = 0.1–0.4, contrary to the cases of bulk samples3 and films on MgO substrates13. These facts indicate that FeSe1−xTex films with x = 0–0.5 on LAO are single-phase samples, as films on CaF2 substrates12.

(a) XRD patterns for FeSe1−xTex thin films with x = 0–0.5 on LAO substrates. Sharps represent the peaks resulting from the substrates. Enlarged plots of (a) around the 001 and 004 peaks are shown in (b) and (c), respectively. (d) Dependence of the c-axis lengths for FeSe1−xTex thin films on the nominal Te content, x. Circles and squares represent the data for films on LAO and CaF28,12,20, respectively. (e) Relationships between the a-axis and c-axis lengths in FeSe1−xTex films with x = 0–0.7. Closed and open symbols are the data of films on LAO and CaF2, respectively. The lattice parameters for FeSe1−xTex polycrystals with x = 0,0.5,0.6 and 0.7 are also plotted as the symbol of a cross. The dashed lines are guides for the eye. We cited the data of FeTe films on LAO and films on CaF2 from previous works3,8,12,20,21.

The c-axis lengths of FeSe1−xTex thin films on LAO are plotted as a function of x in Fig. 1d, where the data for films on CaF28,12,20 are also plotted for comparison. The c-axis lengths of the films on LAO exhibit almost linear dependence on x including two end member materials, FeSe and FeTe21, as in the case of films on CaF212. This suggests that Te contents of the grown films are nearly identical to the nominal values of the targets. Therefore, the above results show that the phase separation in FeSe1−xTex is successfully suppressed in films on LAO substrates, and that these suppressions are realized regardless of substrate materials in the film fabrication process. There are some variations of the c-axis lengths even in the films with the same composition, which is particularly notable at x = 0–0.2. We believe this fact is not due to the variation in the Te content12. Figure 1e shows the relation between the a-axis and the c-axis lengths in FeSe1−xTex films on LAO and CaF28,12,20. For the samples with the same Te content, the c-axis and the a-axis lengths show a weak negative correlation regardless of the substrate materials, which cannot be explained by a variation in Te content because it should result in a positive correlation. This behavior observed in c v.s. a can be explained by considering the Poisson effect. Namely, the c-axis length slightly changes by the in-plane lattice strain depending on the film thickness or substrate materials. These results indicate that there is little variation in the Te content among the films with the same x.

Figure 2a–e show the temperature dependence of the electrical resistivity, ρ, of FeSe1−xTex thin films (x = 0–0.4) on LAO substrates with different film thicknesses. The residual resistivity ratio, RRR(= ρ(300 K)/ρ(20 K)), of these films decreases with increasing x except for x = 0. FeSe films on LAO with thickness of 67 and 250 nm show smaller RRR of approximately 2 than x = 0.1 (RRR ∼ 6) and an FeSe film on a CaF2 substrate (RRR ∼ 4)8. We found that an annealing process is effective for obtaining an FeSe film with a large RRR value. The red-open squares in Fig. 2a represent the temperature dependence of ρ for the FeSe film with thickness of 45 nm, which was kept at 450 °C for 15 minutes after film deposition in the same chamber. The RRR value for the annealed FeSe film is increased to 7. While an annealing improved the RRR values, Tc did not depend on them. Note that a kink anomaly is observed in the ρ–T curve of the annealed FeSe film below 100 K. The temperature dependence of the temperature differentials of logρ for films with x = 0–0.4 are shown in Fig. 2g–k. The annealed FeSe film shows a clear dip structure in the curve of dlogρ/dT (Fig. 2g), and the characteristic temperature, T*, where dlogρ/dT takes its local minimum value (shown by a downward arrow in Fig. 2g) is estimated to be approximately 91 K for the annealed FeSe film. In FeSe bulk single crystals with very large RRR values, the kink in ρ(T) and the local minimum in the differential resistivity are known to be due to the structural transition from tetragonal to orthorhombic14,15,16,17. Thus, it is reasonable to regard that the structural transition occurs at T* in the annealed FeSe film. On the other hand, the as-grown FeSe films do not show a clear kink structure in ρ(T) (Fig. 2a); instead, a peak was observed in dlogρ/dT as shown in Fig. 2g. It is noteworthy that the temperature where the peak is observed in dlogρ/dT is almost the same as T* of the annealed FeSe film. Additionally, in FeSe poly crystals and single crystals with relatively small RRR values, it has been known that there is no clear kink in the ρ–T curves. Instead, a peak is observed in the differential resistivity18,19. This peak appears at approximately 90 K18,19, which is also found to be due to the structural transition. Therefore, not only the annealed film but also the as-grown films show the structural transition at T* as FeSe bulk samples. The differences of the behaviors in ρ(T) and dlogρ/dT around T* between the as-grown and annealed films are considered to result from the differences of RRR values. Thus, we define T* as the temperature where dlogρ/dT takes its local minimum (maximum) for films with large (small) RRR values, and try to estimate T* also at other compositions. Then, we obtained T* ~ 81 K for x = 0.1, T* ~ 64 K for x = 0.2, and T* ~ 44–48 K for x = 0.3 as shown by downward arrows in Fig. 2g–j. On the other hand, for FeSe1−xTex films with x = 0.4 (Fig. 2k), there is no peak- nor dip-structure in d log ρ/dT, which monotonically increases with decreasing temperature. This indicates that the structural transition does not occur at this composition.

Temperature dependence of the electrical resistivity, ρ, of FeSe1−xTex thin films for (a) x = 0, (b) x = 0.1, (c) x = 0.2, (d) x = 0.3, and (e) x = 0.4 fabricated on LAO with different thicknesses. (f) Temperature dependence of the normalized resistivity for FeSe1−xTex films with the optimum film thickness for obtaining the highest Tc at each composition. The insets of (a–f) present enlarged views around Tc. The temperature differential of a common logarithm of the electrical resistivity, dlogρ/dT, for FeSe1−xTex films with x = 0–0.4 is shown in (g–k).

Next, we discuss Tc as a function of x. Since the superconducting transition temperature depends on the film thickness even for the same x as reported before12,22, we focus on the highest Tc for each x. Figure 2f shows the temperature dependence of the normalized resistivity for FeSe1−xTex films on LAO with the optimum film thickness for obtaining the highest Tc at each x. The onset temperature of the superconducting transition,  , of the films in Fig. 2f and T* are plotted as a function of x in Fig. 3, where Tc and T* for films on CaF28,12,20 (See the supporting information) and Tc of bulk samples3,23 are also plotted for comparison. Additionally, we set an error bar for considering slight deviations of T* at each compositions in Fig. 3. The FeSe1−xTex films on LAO show the highest Tc of 19 K at x = 0.4, which is higher than the maximum of Tc in FeSe1−xTex bulk samples at ambient pressure3,23, but lower than that in films on CaF2. We should note that Bellingeri et al. previously reported Tc of 21 K in FeSe0.5Te0.5 film on LAO22, which is higher than our Tc with the same composition, but is rather similar to Tc of our film with x = 0.4. The lattice parameters reported in ref. 22 are much smaller than those of FeSe0.5Te0.5 bulk samples and almost the same as those of our films with x = 0.4. Thus, we consider that the Te content of the film in ref. 22 is close to that of our film with x = 0.4, and that the optimum Te content for FeSe1−xTex films on LAO is x = 0.4. In Fig. 3, there are several common important features in Tc as a function of x between films on LAO and CaF2. At first, the highest Tc in FeSe1−xTex films is obtained at or near the “phase-separation region”. This enhancement of Tc seems to be consistent with a theory based on the electron-density wave fluctuation, which predicts that a high Tc phase is always next to the phase-separation region24. Second, the dependence of Tc on x suddenly changes at a certain Te content, xc, in films on both substrates; Tc increases with decreasing x for x ≥ xc, while Tc strongly suppressed for x < xc. The xc values depend on the substrate materials; xc = 0.4 for films on LAO and xc = 0.212 for films on CaF2. The increase of Tc with decreasing x for x ≥ xc can be explained by an empirical law between Tc and the bond angle of chalcogen-iron-chalcogen, α25, as was discussed in the previous paper12. However, the sudden decrease of Tc is inconsistent with this empirical law. To understand the origin of this nontrivial behavior, we focus on the relation between xc and T*. T* decreases with increasing x, and is observed only at x < xc. This result suggests that xc corresponds to the Te content where T* becomes zero. The same thing is also valid for films on CaF2, while we observe T* only for x = 0 and 0.1. The highest Tc for films on each substrates is realized just at xc, that is, the Te content where T* disappears. The phase diagram of Fig. 3 indicates that the tellurium content necessary to suppress the structural transition varies depending on the kinds of substrate materials. Taking the similarity between films on CaF2 and LAO into consideration, the main origin of the sudden change in Tc at xc is the presence or absence of the structural transition, and the control of the structural transition is essential to obtain higher Tc in iron chalcogenides. If we can suppress T* at smaller x in some way, for example by the introduction of some buffer layers, we expect higher Tc. Looking at Fig. 3 carefully, the dependence of Tc on x at x < xc differs between films on CaF2 and LAO. In terms of the empirical law of α v.s. Tc, Tc should also increase with decreasing x at 0 ≤ x < xc, where the structural transition occurs at low temperatures. Indeed, Tc for films with x = 0 is higher than that with x = 0.1 in the case of CaF2 substrate. For films with x < xc on LAO, however, Tc decreases with decreasing x, which is contrary to the empirical raw. This discrepancy might be due to the unexpected composition dependence of in-plane lattice parameters. In Fig. 1(d), the c-axis lengths for films on LaAlO3 with x = 0–0.3 systematically changes with x, which means that actual Te contents of the films vary with the nominal Te composition, x, as was already discussed. On the other hand, the a-axis lengths for films on LaAlO3 with x = 0–0.3 do not change almost at all as shown in Fig. 1(e). Since the Te substitution increases the lattice parameters both in the a- and c- directions for bulk samples, the small changes in the a-axis lengths of films on LAO with x = 0–0.3 show that the compressive strain is relatively weakened and that the local structures containing the bond angles for films on LaAlO3 with x = 0–0.3 are somewhat different from those for films with x > xc on LaAlO3 and films on CaF2, which may be the origin of the characteristic dependence of Tc at x < xc. The reason for the small changes of the a-axis lengths for films on LaAlO3 with x = 0–0.3 is not clear at this moment. The measurement of the fine structure at the interface provides an important information on it, which is currently undergone. Finally, we briefly comment on the comparison between our phase diagram (Fig. 3) and the pressure-temperature (P–T) phase diagram26. The decrease of T* with increasing x in the phase diagram of Fig. 3 clearly shows that the structural transition is suppressed by the Te substitution of Se, which is consistent with the fact that the tetragonal phase is maintained at low temperatures in FeSe0.5Te0.5 bulk samples. On the other hand, the structural transition also disappears by introducing the physical pressure to FeSe. It is an open question why the structural transition is suppressed by both the physical pressure and the Te substitution, which introduces a negative chemical pressure to FeSe. Interestingly, however, the values of Tc suddenly increases at a pressure where a structural transition is suppressed according to the recently-reported P–T phase diagram of FeSe bulk single crystals26. We should note that the long-range magnetic order is induced after the suppression of the structural transition under high pressures in FeSe26, while there are no signatures of a magnetic transition in the transport properties of our films as shown in Fig. 2. Nevertheless, the rapid increase of Tc at the pressure, where a structural phase transition disappears, in FeSe is very similar to the jump of Tc at xc seen in Fig. 3, which supports our conclusions.

, of the films in Fig. 2f and T* are plotted as a function of x in Fig. 3, where Tc and T* for films on CaF28,12,20 (See the supporting information) and Tc of bulk samples3,23 are also plotted for comparison. Additionally, we set an error bar for considering slight deviations of T* at each compositions in Fig. 3. The FeSe1−xTex films on LAO show the highest Tc of 19 K at x = 0.4, which is higher than the maximum of Tc in FeSe1−xTex bulk samples at ambient pressure3,23, but lower than that in films on CaF2. We should note that Bellingeri et al. previously reported Tc of 21 K in FeSe0.5Te0.5 film on LAO22, which is higher than our Tc with the same composition, but is rather similar to Tc of our film with x = 0.4. The lattice parameters reported in ref. 22 are much smaller than those of FeSe0.5Te0.5 bulk samples and almost the same as those of our films with x = 0.4. Thus, we consider that the Te content of the film in ref. 22 is close to that of our film with x = 0.4, and that the optimum Te content for FeSe1−xTex films on LAO is x = 0.4. In Fig. 3, there are several common important features in Tc as a function of x between films on LAO and CaF2. At first, the highest Tc in FeSe1−xTex films is obtained at or near the “phase-separation region”. This enhancement of Tc seems to be consistent with a theory based on the electron-density wave fluctuation, which predicts that a high Tc phase is always next to the phase-separation region24. Second, the dependence of Tc on x suddenly changes at a certain Te content, xc, in films on both substrates; Tc increases with decreasing x for x ≥ xc, while Tc strongly suppressed for x < xc. The xc values depend on the substrate materials; xc = 0.4 for films on LAO and xc = 0.212 for films on CaF2. The increase of Tc with decreasing x for x ≥ xc can be explained by an empirical law between Tc and the bond angle of chalcogen-iron-chalcogen, α25, as was discussed in the previous paper12. However, the sudden decrease of Tc is inconsistent with this empirical law. To understand the origin of this nontrivial behavior, we focus on the relation between xc and T*. T* decreases with increasing x, and is observed only at x < xc. This result suggests that xc corresponds to the Te content where T* becomes zero. The same thing is also valid for films on CaF2, while we observe T* only for x = 0 and 0.1. The highest Tc for films on each substrates is realized just at xc, that is, the Te content where T* disappears. The phase diagram of Fig. 3 indicates that the tellurium content necessary to suppress the structural transition varies depending on the kinds of substrate materials. Taking the similarity between films on CaF2 and LAO into consideration, the main origin of the sudden change in Tc at xc is the presence or absence of the structural transition, and the control of the structural transition is essential to obtain higher Tc in iron chalcogenides. If we can suppress T* at smaller x in some way, for example by the introduction of some buffer layers, we expect higher Tc. Looking at Fig. 3 carefully, the dependence of Tc on x at x < xc differs between films on CaF2 and LAO. In terms of the empirical law of α v.s. Tc, Tc should also increase with decreasing x at 0 ≤ x < xc, where the structural transition occurs at low temperatures. Indeed, Tc for films with x = 0 is higher than that with x = 0.1 in the case of CaF2 substrate. For films with x < xc on LAO, however, Tc decreases with decreasing x, which is contrary to the empirical raw. This discrepancy might be due to the unexpected composition dependence of in-plane lattice parameters. In Fig. 1(d), the c-axis lengths for films on LaAlO3 with x = 0–0.3 systematically changes with x, which means that actual Te contents of the films vary with the nominal Te composition, x, as was already discussed. On the other hand, the a-axis lengths for films on LaAlO3 with x = 0–0.3 do not change almost at all as shown in Fig. 1(e). Since the Te substitution increases the lattice parameters both in the a- and c- directions for bulk samples, the small changes in the a-axis lengths of films on LAO with x = 0–0.3 show that the compressive strain is relatively weakened and that the local structures containing the bond angles for films on LaAlO3 with x = 0–0.3 are somewhat different from those for films with x > xc on LaAlO3 and films on CaF2, which may be the origin of the characteristic dependence of Tc at x < xc. The reason for the small changes of the a-axis lengths for films on LaAlO3 with x = 0–0.3 is not clear at this moment. The measurement of the fine structure at the interface provides an important information on it, which is currently undergone. Finally, we briefly comment on the comparison between our phase diagram (Fig. 3) and the pressure-temperature (P–T) phase diagram26. The decrease of T* with increasing x in the phase diagram of Fig. 3 clearly shows that the structural transition is suppressed by the Te substitution of Se, which is consistent with the fact that the tetragonal phase is maintained at low temperatures in FeSe0.5Te0.5 bulk samples. On the other hand, the structural transition also disappears by introducing the physical pressure to FeSe. It is an open question why the structural transition is suppressed by both the physical pressure and the Te substitution, which introduces a negative chemical pressure to FeSe. Interestingly, however, the values of Tc suddenly increases at a pressure where a structural transition is suppressed according to the recently-reported P–T phase diagram of FeSe bulk single crystals26. We should note that the long-range magnetic order is induced after the suppression of the structural transition under high pressures in FeSe26, while there are no signatures of a magnetic transition in the transport properties of our films as shown in Fig. 2. Nevertheless, the rapid increase of Tc at the pressure, where a structural phase transition disappears, in FeSe is very similar to the jump of Tc at xc seen in Fig. 3, which supports our conclusions.

Phase diagram of FeSe1−xTex films. Blue circles (red circles) and light-green stars (orange hexagons) represent  and T* of the FeSe1−xTex thin films fabricated on LAO (CaF28,12,20), respectively. In the inset, the dependence of

and T* of the FeSe1−xTex thin films fabricated on LAO (CaF28,12,20), respectively. In the inset, the dependence of  on Te content x is shown. The values of Tc for bulk samples estimated from the magnetic susceptibility measurements are shown as gray triangles3,23. The dashed curves in the inset are guides for the eye.

on Te content x is shown. The values of Tc for bulk samples estimated from the magnetic susceptibility measurements are shown as gray triangles3,23. The dashed curves in the inset are guides for the eye.

In summary, we succeeded in fabricating epitaxial thin films of FeSe1−xTex with 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.7 by using LaAlO3 substrates, showing that thin film growth by PLD is effective for suppressing phase separation regardless of the substrate materials. In the temperature dependence of ρ and dlogρ/dT, there is an anomaly in films with x = 0–0.3 (LaAlO3) and x = 0–0.1 (CaF2), which corresponds to the structural transition. This means that the Te content necessary to suppress the structural transition can be controlled by changing the substrate materials. In our phase diagram, a sudden change of Tc is commonly observed at a certain Te content, which agrees with the Te content where a structural transition disappears in both films on LaAlO3 and CaF2. Therefore, this sudden change of Tc is related to the structural transition. Our result indicates that one of the key factors to realize a further increase of Tc in iron chalcogenides is the control of the structural transition.

Methods

All of the films in this study were grown by the PLD method with a KrF laser6,27. FeSe1−xTex polycrystalline pellets (x = 0–0.7) were used as targets. The substrate temperature, and the base pressure were 300 °C, and 10−7 Torr, respectively. Commercially available single crystals of LAO (100) were used as the substrates, because LAO is one of the most suitable substrate materials among oxides for the film growth of FeSe1−xTex22,28,29. These films were deposited in a six-terminal shape using a metal mask for transport measurements. The measured area was 1.2 mm long and 1.0 mm wide. The thicknesses of the grown films were measured using a Dektak 6 M stylus profiler. The crystal structures and the orientations of the films were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) with Cu Kα radiation at room temperature. The a-axis and the c-axis lengths were determined from the 204 and 00l reflections in XRD measurements, respectively. The electrical resistivity was measured by using the Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS, Quantum Design, Inc.) from 2 to 300 K.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Imai, Y. et al. Control of structural transition in FeSe1−xTex thin films by changing substrate materials. Sci. Rep. 7, 46653; doi: 10.1038/srep46653 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Kamihara, Y., Watanabe, T., Hirano, M. & Hosono, H. Iron-based layered superconductor la(o1−x f x )feas (x = 0.05–0.12) with t c = 26 k. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3296 (2008).

Hsu, F. C. et al. Superconductivity in the pbo-type structure α-fese. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14262 (2008).

Fang, M. H. et al. Superconductivity close to magnetic instability in fe(se1−x te x )0.82 . Phys. Rev. B 78, 224503 (2008).

Masaki, S. et al. Precise pressure dependence of the superconducting transition temperature of fese: Resistivity and 77se-nmr study. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 78, 063704 (2009).

Medvedev, S. et al. Electronic and magnetic phase diagram of β-fe1.01se with superconductivity at 36.7 k under pressure. Nat. Mater. 8, 630 (2009).

Nabeshima, F., Imai, Y., Hanawa, M., Tsukada, I. & Maeda, A. Enhancement of the superconducting transition temperature in fese epitaxial thin films by anisotropic compression. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 172602 (2013).

Maeda, A. et al. Synthesis, characterization, hall effect and thz conductivity of epitaxial thin films of fe chalcogenide superconductors. Appl. Sur. Sci. 312, 43 (2014).

Imai, Y., Sawada, Y., Asami, D., Nabeshima, F. & Maeda, A. Superconducting properties of fese1−x te x films with x = 0 - 0.4. Physica C 530, 24–26 (2016).

Wang, Q.-Y. et al. Interface-induced high-temperature superconductivity in single unit-cell fese films on srtio 3. Chin. Phys. Lett. 29, 037402 (2012).

Nakayama, K. et al. Reconstruction of band structure induced by electronic nematicity in an fese superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 237001 (2014).

Shimojima, T. et al. Lifting of xz/yz orbital degeneracy at the structural transition in detwinned fese. Phys. Rev. B 90, 121111 (2014).

Imai, Y., Sawada, Y., Nabeshima, F. & Maeda, A. Suppression of phase separation and giant enhancement of superconducting transition temperature in fese1−x te x thin films. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 1937–1940 (2015).

Wu, M. K. et al. The development of the superconducting pbo-type β-fese and related compounds. Physica C 469, 340 (2009).

Böhmer, A. E. et al. Lack of coupling between superconductivity and orthorhombic distortion in stoichiometric single-crystalline fese. Phys. Rev. B 87, 180505 (2013).

Huynh, K. K. et al. Electric transport of a single-crystal iron chalcogenide fese superconductor: Evidence of symmetry-breakdown nematicity and additional ultrafast dirac cone-like carriers. Phys. Rev. B 90, 144516 (2014).

Kasahara, S. et al. Field-induced superconducting phase of fese in the bcs-bec cross-over. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16309–16313 (2014).

Sun, Y., Pyon, S. & Tamegai, T. Electron carriers with possible dirac-cone-like dispersion in fese1−x s x (x = 0 and 0.14) single crystals triggered by structural transition. Phys. Rev. B 93, 104502 (2016).

Mendoza, D., Benítez, J., Morales, F. & Escudero, R. Magnetic anomaly in superconducting fese. Solid State Commun. 150, 1124 (2010).

Song, Y. J. et al. Superconducting properties of a stoichiometric fese compound and two anomalous features in the normal state. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 59, 312 (2011).

Sawada, Y., Nabeshima, F., Imai, Y. & Maeda, A. Investigation of transport properties for fese1−x te x thin films under magnetic fields. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 85, 073703 (2016).

Tsukada, I. et al. Hall effect of fete and fe(se1−x te x ) thin films. Physica C 471, 625–629 (2011).

Bellingeri, E. et al. t c = 21k in epitaxial fese0.5te0.5 thin films with biaxial compressive strain. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 102512 (2010).

Noji, T. et al. Growth, annealing effects on superconducting and magnetic properties, and anisotropy of fese1−x te x (0.5 ≤ x ≤ 1) single crystals. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 79, 084711 (2010).

Misawa, T. & Imada, M. Superconductivity and its mechanism in an ab initio model for electron-doped lafeaso. Nat. Commun. 5, 6738 (2014).

Lee, C.-H. et al. Effect of structural parameters on superconductivity in fluorine-free lnfeaso1−y (ln = la, nd). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 77, 083704 (2008).

Sun, J. P. et al. Dome-shaped magnetic order competing with high-temperature superconductivity at high pressures in fese. Nat. Commun. 7, 12146 (2016).

Imai, Y. et al. Superconductivity of fese0.5te0.5 thin films grown by pulsed laser deposition. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 49, 023101 (2010).

Imai, Y. et al. Systematic comparison of eight substrates in the growth of fese0.5te0.5 superconducting thin films. Appl. Phys. Express 3, 043102 (2010).

Hanawa, M. et al. Substrate dependence of structural and transport properties in fese0.5te0.5 thin films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 50, 053101 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Masafumi Hanawa at CRIEPI (Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry) for his support in the estimation of thickness of our films and Kazunori Ueno (Department of Basic Science, the University of Tokyo) for providing us the X-ray instrument. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 15K17697, 26·9315 and “Nanotechnology Platform” (project No. 12024046) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. I. designed the research and analyzed the data. Y.I., Y.S., F.N., D.A., and M.K. contributed to the film fabrication and the XRD and electrical resistivity measurement. The text of the paper was written by Y.I., Y.S., F.N., and A.M. All the authors contributed to discussion on the results for the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Imai, Y., Sawada, Y., Nabeshima, F. et al. Control of structural transition in FeSe1−xTex thin films by changing substrate materials. Sci Rep 7, 46653 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46653

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46653

This article is cited by

-

Effect of the Buffer Layers on the Performance of Fe(Se, Te) Films Fabricated on IBAD Metal Templates by Pulsed Laser Deposition

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2023)

-

Effects of Te- and Fe-doping on the superconducting properties in FeySe1−xTex thin films

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Effect of sputtering pressure on the superconducting properties of Fe(Te,Se) films

Journal of Materials Science (2022)

-

Light-induced enhancement of superconductivity in iron-based superconductor FeSe0.5Te0.5

Communications Physics (2021)

-

Artificially engineered nanostrain in FeSexTe1-x superconductor thin films for supercurrent enhancement

NPG Asia Materials (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.