Abstract

The loss of biological soil crusts represents a challenge for the restoration of disturbed environments, specifically in particular substrates hosting unique lichen communities. However, the recovery of lichen species affected by mining is rarely addressed in restoration projects. Here, we evaluate the translocation of Diploschistes diacapsis, a representative species of gypsum lichen communities affected by quarrying. We tested how a selection of adhesives could improve thallus attachment to the substrate and affect lichen vitality (as CO2 exchange and fluorescence) in rainfall-simulation and field experiments. Treatments included: white glue, water, hydroseeding stabiliser, gum arabic, synthetic resin, and a control with no adhesive. Attachment differed only in the field, where white glue and water performed best. Adhesives altered CO2 exchange and fluorescence yield. Notably, wet spoils allowed thalli to bind to the substrate after drying, revealing as the most suitable option for translocation. The satisfactory results applying water on gypsum spoils are encouraging to test this methodology with other lichen species. Implementing these measures in restoration projects would be relatively easy and cost-effective. It would help not only to recover lichen species in the disturbed areas but also to take advantage of an extremely valuable biological material that otherwise would be lost.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological soil crusts (BSCs), consisting of complex associations of lichens, mosses, algae, cyanobacteria, and other organisms are remarkable components of dryland ecosystems worldwide1. They play a critical role in their structure and function, acting on soil stability, biogeochemical cycling, and plant establishment1,2,3. These crusts are particularly notable in gypsum ecosystems, and are normally dominated by lichens1,4,5. They have a high conservation value due to their potential to form covers (sometimes >80%), their function, and their diversity6,7,8. However, large extensions covered by BSCs are disturbed by human activities9,10, quarrying inflicting particularly severe damage6,11. Gypsum is a mineral in global demand12 and its quarrying inevitably damages BSCs and their habitat. Despite that mining companies are obligated to conduct environmental restoration (e.g. geomorphology and plant cover), BSCs are normally ignored. Limitations such as the slow growth of their components, low reproduction rates, the destruction of propagules and habitat together with the lack of a clear restoration methodology make the recovery of BSCs especially challenging3,10,13,14.

Few studies have addressed the assisted recovery of BSCs. Practice to enhance BSC establishment include soil stabilisation, resource augmentation, and inoculation-based techniques10. Inoculation is the best-studied and consists of adding cultured or salvaged BSC components to increase propagule availability in the disturbed area14,15,16,17. The recovery of cyanobacteria and algae has been achieved in gypsum BSCs over the short term14,15,16. However, the recovery of later successional components such as lichens can be extremely slow unless these are translocated9,14,15. Lichen translocation can be particularly advisable to accelerate species recolonisation in the disturbed area, but the loss of thalli due to environmental factors (e.g. wind, rain-storms) can arrest or greatly delay establishment9,18.

The attachment of propagules to the substrate is key for full lichen development (e.g. nutrient and moisture intake, hyphae formation, and favourable reproduction)19,20 and acts as one of the main ecological filters for colonisation and recovery21. The first step for propagules is to attach to the substrate in an entirely physical process20. Thereafter, propagules start to grow hyphae and actively attach to the substrate20. Otherwise, dispersed propagules remain erratic at risk of being removed off by wind22 or water23 and lost. Thus, keeping thalli in place would be useful in reducing their loss, favouring establishment, and eventually augmenting the source of propagules over time to hasten BSC recovery. Accordingly, a range of adhesives has been used previously for lichen translocation on different substrates (see Smith24 for a review), terricolous habitats being especially challenging. The aim of our study is to assess thallus translocation for restoration using a representative species of gypsum lichen communities [Diploschistes diacapsis (Ach.) Lumbsch]. We tested whether the application of various adhesives could improve thallus attachment onto gypsum mine spoil without compromising their vitality. The results may be helpful for future restoration programs to recover BSCs in disturbed gypsum habitats.

Material and Methods

Site description

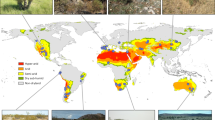

The field work was conducted in an experimental area next to an active quarry in Escúzar, Granada, SE Spain (37°2′N, 3°45′W) at 950 m asl. The climate is continental Mediterranean, with relatively cold winters, hot summers, and four months of water deficit. The mean annual temperature is 15.1 °C, with an average monthly minimum temperature in January of 7.6 °C and maximum of 24.2 °C in August. The annual rainfall, occurring mainly in winter, averages 420 mm. The area is in the Neogene sedimentary basin of Granada, where the dominant substrates are lime and gypsum deposited in the late Miocene, the latter in combination with marls25. The predominant soils where gypsum crops out are Gypsiric Leptosols26,27. The vegetation of the area is a mosaic of fields with cereal crops and olive and almond orchards (Olea europaea L. and Prunus dulcis D.A. Webb.), and scattered patches of native scrub described as 1520, “Iberian gypsum vegetation, Gypsophiletalia”28. Open areas between native plants are often colonised by a well-developed biocrust community characterised by lichens such as D. diacapsis, Acarospora placodiiformis, A. nodulosa var. reagens, Buellia zoharyi, Squamarina lentigera, S. cartilaginea, F. desertorum, F. fulgens, F. poeltii, F. subbracteata, Psora decipiens, and P. saviczii (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table S1).

(a) Soil crust community on gypsum soil dominated by the lichen Diploschistes diacapsis in a Mediterranean gypsum shrub community in Granada, Spain. (b) D. diacapsis growing on gypsum soil. (c and d) Thalli of D. diacapsis used in our experiments to test for the effect of various adhesives on thallus attachment to gypsum spoil; (c) in trays during the rainfall-simulation (see arrows), and (d) in one of the plots when the field experiment was set up in March 2014.

Study species

D. diacapsis (Fig. 1b), is a sub-cosmopolitan terricolous crustose lichen species occurring mainly on calcareous and gypsaceous soils in open xeric habitats in Mediterranean and arid climates1,29,30. This lichen species has a thick thallus (1–3 mm) of variable aspect, verrucose-areolate with urceolate apothecia and white pruina31. It is one of the most frequent lichens in gypsum BSCs in the Iberian Peninsula, normally reaching the greatest cover and biomass (~40% cover4; ~55% cover and >80% biomass in the study area according Ibarz32). Having a central role in gypsum communities, it acts as host to numerous fungi and lichen species33. D. diacapsis was selected as a model species for its dominance at the study site and for its similar ecology and morphology with respect to other crust-forming lichens in gypsum habitats (e.g. Acarospora, Buellia, Squamarina, Lecidea)34.

Common set up for rainfall-simulation and field experiments

Thallus collection

In March 2014, thalli were detached at the study site from the parent gypsum substrate and collected from shrub interspaces in the area where quarrying was scheduled. The samples were taken immediately to the laboratory in paper bags. Thalli were soaked in tap water (for 5–10 min), cleaned and die cut into disks of 15 mm to obtain homogeneous experimental units. Thalli were transferred to be used, respectively, in rainfall-simulation and field experiments within the next 24 hours.

Substrate used

Gypsum spoil was assayed as the recipient substrate for translocation (properties in Supplementary Table S2). It is a by-product of gypsum quarrying normally used to fill quarry pits and reshape the landscape after quarrying. Pilot studies have confirmed its suitability to conduct gypsum vegetation recovery35,36. This material, often remaining in the quarried areas, is a suitable substrate to test lichen and adhesive performance.

Adhesive treatments

Several commercial natural or synthetic adhesives were applied to thalli in rainfall-simulation and field experiments. These included: (1) white glue (G): wood and craft white glue consisting of polyvinyl acetate (Wolfpack, A Forged Tool S.A.); (2) hydroseeding stabiliser (HS): synthetic polyacrylamide polymer (Bonterra Ibérica S.L.) as powder dissolved in water at 5 g/L; (3) gum arabic (GA): a complex of glycoproteins and polysaccharides derived from Acacia tree exudates (Prager, Orita S.A.); (4) synthetic resin (SR): contact adhesive polymeric glue (Kollant, Impex Europa S.L.); and (5) water (W): wetting spoil with water. A control treatment (C) where no adhesive was applied to thalli was used in both experiments. The adhesives were used at their commercial concentrations.

Rainfall-simulation experiment

We tested the effect of adhesives on thallus attachment under controlled rainfall and slope conditions in a rainfall-simulation experiment recreating the effect of two separate disturbing rain events. In March 2014, 30 plastic trays (35 × 25 × 5 cm) were perforated to allow drainage, filled with gypsum spoil (sieved at 0.5 cm; approx. 2.5 Kg), watered, and left to dry in order for the spoil to gain cohesion. Ten thalli were transferred to each of five replicate trays after applying one of the six adhesive treatments (2 ml with a 200-ml syringe) to the lower surface of the thallus (i.e. closest side to substrate), except for the water treatment, which was applied by spraying tap water (~100 ml) to moisten the tray substrate (10 thalli × 5 replicates × 6 adhesive treatments = 300 thalli). Thalli were placed in two lengthwise parallel rows (5 each) in the middle of the tray (Fig. 1c), using a quadrat with a 5 × 5 cm grid, which also served to monitor detachment after rainfall simulations. Simulations were conducted in a greenhouse, using a rainfall simulator (modified from Fernández-Gálvez et al.37), consisting of a drop-forming chamber (controlled by a pump connected to a water reservoir) on top of a structure (2 m high) that housed two random trays at the same time tilted for a 25° slope (near the angle of rest of the spoil material to simulate an extreme situation). We conducted two 15-min simulations at 50 l·m2·h intensity (selected according to rainfall record in the study area from 2000 to 2013) in consecutive weeks, allowing the substrate to dry in between. We visually checked thallus detachment after each simulation, removing detached thalli to avoid interference on the following check. Once the substrate dried after the second simulation, we assessed thallus attachment by manual inspection applying gentle sideways pressure on the thalli to verify whether the thalli were attached or moved without resistance. We measured CO2 exchange as an indicator of thallus vitality after adhesive application38,39. The thalli used in the rainfall simulation were left in their trays outdoors for two months (May-June) under ambient conditions. The CO2 exchange was measured with an infrared gas analyser (EGM-4 Environmental Gas Monitor and a SRC-1 Soil Respiration Chamber, PP systems, Hitchin, U.K.). Six thalli per tray (30 per treatment) were moistened and placed together inside the chamber (to improve CO2 detection) on a sterile plastic surface (to avoid substrate interference in the measurements). Five measurements per treatment were performed by alternating treatments. Measurements were taken between 10:00 and 13:00 h (local time, GMT + 1). This period is considered representative of daily averages of CO2 exchange for these lichens40,41.

Field experiment

The experiment was set up in March 2014 on a conditioned flat area consisting of bare gypsum spoil generated from gypsum quarrying. A total of 30 permanent plots of 0.5 × 0.5 m were established with a randomised design, including 5 replicate plots per each of the 6 adhesive treatments. In the centre of each plot (Fig. 1d), 35 thalli were positioned using a 50 × 50 cm quadrat with a 5 × 5 cm grid (5 replicate plots × 6 treatments × 35 thalli = 1050 thalli). Each thallus was transferred and fixed to the centre of a grid square with the corresponding plot adhesive applying gentle pressure to attach it, and its position was identified in order to record thallus detachment over time. Thalli were fixed by applying an adhesive treatment (2 ml with a 200-ml syringe) to the lower surface of the thallus, except for the water treatment, which was applied by spraying tap water (~200 ml) to moisten the plot substrate. We monitored lichens visually for thallus detachment over a 15-month period (March 2014 to May 2015), weekly during the first three months and monthly afterwards. Detached thalli were removed to avoid interference on the following sampling dates. Additionally, we measured chlorophyll fluorescence using the ratio Fv/Fm as an indicator of lichen vitality 16 months (June, 2015) after the application of the adhesives. Chlorophyll fluorescence is a sensitive indicator of photosystem II (PSII) efficiency, used to detect stress and to assess lichen vitality39,42,43. Fluorescence was measured on 10 thalli (when available) per replicate plot with a chlorophyll fluorimeter (Handy PEA, Hansatech Instruments, Norfolk, U.K.) on soaked (with a spray of water) and dark-adapted (measured by night) samples, applying a saturating flash of light of 3580 μmol s−1 m−2 for 1 s. As a reference of vital lichens, we included 50 15-mm thalli prepared with fresh material collected from the undisturbed habitat (Hab) two hours before the measurements were taken following the same procedure, and we evaluated the efficiency of PSII by measuring the Fv/Fm ratio44.

Data analyses

We assessed the effect of adhesives on thallus attachment over time using the Kaplan-Meier log-rank survival analysis (R “survival” package45) and fitting mixed-effects Cox proportional hazard models (R “coxme” package46) using trays or quadrats as random factors, respectively, in rain-simulation or field experiments. The effect of adhesives on CO2 exchange in rainfall simulations was evaluated by fitting generalised linear models (GLMs) with a Poisson error distribution and log link function (R “stats” package47). We tested for the effect of adhesives (i.e. fixed factor) on fluorescence yield in the field experiment, fitting generalised linear mixed models (GLMMs) with a binomial error distribution and logit link function, using quadrats as random factors (R “lme4” package48). Model parameters were estimated using the Laplace approximation of likelihood. Pairwise multiple comparisons with Tukey’s correction (R “multcomp” package49 were made to estimate differences between adhesive treatments. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.2.247.

Results

Rainfall-simulation experiment

Rain simulation showed 100% attachment in G, W, and GA and very high for the rest of treatments at the end of the experiment (SR, 98%; HS, 94% and C, 82%; Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S1). As expected, treatment C recorded the lowest attachment, although the post hoc analysis indicated no differences with respect to the other treatments. All treatments had lower detachment risk than did C (Table 1, Cox regression). Thalli detached during the first simulation only in treatments C (12% detachment) and HS (2%), and no detachment was found during the second one. Manual inspection after the substrate dried showed additional detachment in treatments C (6% detachment), HS (4%), and SR (2%). Remarkably, the remaining thalli on the C treatment were attached at the end of this experiment. The analysis of CO2-exchange measurements taken on thalli detached for this purpose at the end of the experiment showed significant differences between adhesives, with higher respiration rates in C, HS, W, GA, G, and SR in descending order (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S3).

Field-experiment

After a 15-month follow-up of the field experiment, our results showed that the adhesive treatment significantly affected thallus attachment (Fig. 3; Table 2). Responses varied depending on the adhesive, with better results in G (87.4% attachment), W (80%), HS (59.9%), GA (54.3%), C (45.7%), and SR (36.6%) in this order, with significant differences between G and W compared to the rest (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier curves showed only moderate detachment in G and W and significantly greater in the rest of the treatments (Fig. 3). Treatment C plummeted in the first month, followed by steady detachment until declining almost completely towards the eighth month. Detachment was more gradual in HS, GA, and SR, with the first two listed treatments with little detachment from the tenth month onwards, and the latter falling steadily until the end of the follow-up, even underperforming the C treatment (Fig. 3). The Cox proportional hazard analysis also showed significant differences between treatments. All treatments reduced the risk of detachment compared to the control, except SR, which presented a similar risk (Table 2, Cox regression). The photosynthetic activity as Fv/Fm for the treatments was C (0.16), SR (0.18), W (0.22), HS (0.24), GA (0.25), Hab (0.28) and G (0.31), with significant differences only between C, and G, and Hab (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S4).

Discussion

Our findings indicated that white glue, water, hydroseeding stabiliser and gum arabic improved the attachment of D. diacapsis thalli, although they also altered lichen vitality. Remarkably, the water treatment (i.e. wetting the spoils) significantly improved thallus attachment without compromising their vitality, which would be especially advantageous to optimise crust material in translocation actions.

Thallus attachment to the substrate was similar for all adhesives in rainfall simulations. Although the thalli were exposed to considerable rain intensity and inclination in this experiment, the level, angle or time exposed to these factors were not sufficient to show differences between treatments. By contrast, thallus attachment differed depending on the adhesive when exposed to field conditions over a longer period (differences were noticeable from the first month onwards). The difference between experiments appears to be explained by the greater exposure time in the field to rain and wind. These factors can encourage lichen dispersal in open areas4,21, but for the same reason they can also make it difficult for thalli to remain at the same specific site, hindering establishment. In our field experiment, we found thallus attachment using white glue and water was greatest and remarkably better than for the other treatments throughout the follow-up. By contrast, the performance of hydroseeding stabiliser and gum arabic was inferior and similar to the control towards the end of the experiment. Although the attachment achieved with the synthetic resin was similar to that using the hydroseeding stabiliser and gum arabic for nearly 8 months, it lost its adhesive properties and eventually registered the lowest results.

Our results suggest that water followed by substrate drying played a central role in thallus attachment. Although we assumed a priori that making the spoils wet would have an antagonistic effect on thallus attachment, the opposite happened in both the rainfall-simulation and field experiments. In rainfall simulations, most of the thalli in all treatments were attached to the substrate after it dried, this being especially remarkable in the control treatment, where no adhesive had been applied, but where water acted as such after the first simulation. This pattern was observed in the field also. Most thalli in the control treatment detached in the first two months but stabilised afterwards despite heavy rain in the following months. In fact, all treatments seemed to stabilise except the synthetic resin. A possible explanation is that the synthetic resin is a hydrophobic adhesive and remained on the thalli, preventing them from reattaching. While water may weaken the relationship between thalli and the substrate during a rain event, it also helps to create some bonds with the substrate surface18,50. The surface becomes sticky due to the high cohesiveness of silt and clay particles when mixed with moderate amount of water. Then the drying process makes these bonds more stable, helping lichens to attach. This pattern has been reported in nature (e.g. with seeds51 or soil particles52) and, as our results reveal, it is one of the ways lichen propagules create bonds and attach to certain substrates.

Another key issue is how the different treatments affect thallus vitality. A given adhesive could aid thallus attachment, but if significantly harmed the lichen’s physiology, then use of the product would be unacceptable. In this regard, vitality measurements determined that some of the treatments tested reduced thallus activity, although no one was so aggressive as to completely inhibit respiration or photosynthetic processes. The results of CO2 exchange showed thallus activity in rainfall simulations to be reduced by the adhesive applied. The highest respiration rate was registered in the control treatment, followed by the hydroseeding stabiliser, water, and the rest of treatments. Contrary to expectations, the water treatment differed from control despite that thalli in both treatments were treated only with water (prior or during the rainfall simulation). Although the CO2 exchange was not as high as in the control treatment, thalli treated with water were active and there is no apparent reason why water would reduce their vitality, but rather the opposite. In the field experiment, the efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) used as stress indicator53 showed no differences between the thalli translocated using adhesives and those freshly collected in the undisturbed habitat. Although no significant differences were found between treatments, with the use of the synthetic resin, thalli showed reduced activity and some signs of necrosis, and thus this adhesive is not recommendable. The control treatment recorded the lowest value, probably due to the lowest attachment to the substrate. The activity for all the other adhesives was between 0.22 and 0.31, and the activity for thalli in the habitat (Hab) used as reference was within this range (0.28). These values are similar to PSII efficiency on undisturbed north and south-facing populations of D. diacapsis studied in Pintado et al.54, estimated, respectively, as 0.25 and 0.28 by Maestre et al.3. Thus, we can infer that translocation onto the gypsum spoil using most of the adhesives studied here was not so stressful as to alter the photosynthetic process and make the Fv/Fm differ from nature.

Therefore, our results suggest that translocation can help some components of the BSCs to recover. We have demonstrated that D. diacapsis is amenable to translocation and can be moved from its habitat onto gypsum spoils, but this methodology could be extended to other gypsum-crust components in substrates having similar properties (i.e. disturbed original habitat or topsoil used for restoration). More than 50% of the lichen species in gypsum habitats have similar morphology and ecology4 and the use of this methodology with them is especially appealing. In addition, other terricolous lichen communities on similarly performing substrates in other drylands could benefit from this approach. The crust material can be salvaged from donor habitats prior quarrying. Complete thalli or fragments can be scalped from the parent material along with other BSCs species14,15. This material could be applied directly or stored for relatively long periods providing some flexibility for translocation actions10,14. The recipient substrate can be sprayed with water to create a sticky surface to receive the crust material, and then let the substrate dry until the thalli bind, as our results reveal.

Areas meeting the environmental requirements that define the occurrence of these crusts should be selected for translocation24. Their occurrence has been related to variables such as substrate stability4,55, orientation and water availability54, soil respiration55, and complex relations with the surrounding vegetation3,55,56,57. Accordingly, Martínez et al.55 reported that high bare-soil cover and low plant-litter cover were positively related to the presence of gypsum crustose lichens. While this scenario is frequent right away after quarrying, invasive early successional plant species (e.g. Dittrichia viscosa, Pitptatherum milliaceum, Moricandia arvensis, in our area) could strongly reduce open areas available for lichens over the short term. Thus, where possible, it would be advisable to translocate lichens to plant interspaces in areas where gypsum vegetation had already developed (naturally or restored) aiding it to escape early successional competitors. Additionally, these areas would provide a gradient of conditions for translocation, depending on crust species-specific requirements related to plant proximity (shade, moisture, organic matter, etc.55,56,57,58. Other components of gypsum BSCs (i.e. cyanobacteria and algae) have been reported to develop comparatively fast through colonisation15 or inoculation14,15,16. Thus, a combination of translocation with additional inoculation measures16 or the use of already colonised substrates (i.e. restored gypsum spoils, topsoil, disturbed original habitat) could help facilitate certain limiting processes (e.g. contact between mycobiont spores and photobionts59) and promote a more complete recovery of gypsum BSCs.

In conclusion, here we have shown that the use of certain adhesives can significantly increase lichen attachment to the substrate without compromising their vitality. Particularly, our study shows the central role that water and the subsequent drying of the substrate play for thallus attachment, and offers a methodology with implications for restoration of disturbed gypsum BSCs. This study represents one of the first studies to evaluate the translocation of lichens in gypsum drylands and the first to test adhesives for lichen attachment onto gypsum quarry spoils. This methodology needs to be tested over time using other species and considering disturbances in gypsum habitats. Further protocols should be designed, assessing the ecological, technical, and economic viability of translocation, in order to confirm their applicability to large-scale restoration of gypsum BSCs. The results in the present study are encouraging and open an opportunity to accelerate the recovery of BSCs in disturbed gypsum habitats.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ballesteros, M. et al. Successful lichen translocation on disturbed gypsum areas: A test with adhesives to promote the recovery of biological soil crusts. Sci. Rep. 7, 45606; doi: 10.1038/srep45606 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Belnap, J. & Lange, O. L. Biological Soil Crust Structure and Function. (Springer-Verlag, 2003).

Bowker, M. A., Maestre, F. T. & Escolar, C. Biological crusts as a model system for examining the biodiversity-ecosystem function relationship in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 405–417 (2010).

Maestre, F. T. et al. Ecology and functional roles of biological soil crusts in semi-arid ecosystems of Spain. J. Arid Environ. 75, 1282–1291 (2011).

Gutiérrez, L. & Casares, M. In Diversidad Vegetal de las Yeseras Ibéricas. El reto de los archipiélagos edáficos para la biología de la conservación (eds Mota, J. F., Martínez-Hernández, F. & Guirado, J. S. ) 551–567 (ADIF-Mediterráneo Asesores Consultores, 2011).

Lalley, J. S. & Viles, H. A. Recovery of lichen-dominated soil crusts in a hyper-arid desert. Biodivers. Conserv. 17, 1–20 (2008).

Belnap, J. et al. Biological soil crusts: ecology and management. US Dept. Inter. TR 1730–2 (2001).

Guerra, J., Ros, R. M., Cano, M. J. & Casares, M. Gypsiferous outcrops in SE Spain, refuges of rare, vulnerable and endangered briophytes and lichens. Cryptogam. Bryol. 2, 125–135 (1995).

Root, H. T., Miller, J. E. D. & McCune, B. Biotic soil crust lichen diversity and conservation in shrub-steppe habitats of Oregon and Washington. Bryologist 114, 796–812 (2011).

Belnap, J. & Eldridge, D. In Biological Soil Crusts: Structure, Function, and Management (eds Belnap, J. & Lange, O. L. ) 150, 363–383 (Springer-Verlag, 2003).

Bowker, M. A. Biological soil crust rehabilitation in theory and practice: An underexploited opportunity. Restor. Ecol. 15, 13–23 (2007).

Mota, J. F., Sola, A. J., Jiménez-Sánchez, M. L., Pérez-García, F. & Merlo, M. E. Gypsicolous flora, conservation and restoration of quarries in the southeast of the Iberian Peninsula. Biodivers. Conserv. 13, 1797–1808 (2004).

Herrero, M. J., Escavy, J. I. & Bustillo, M. The Spanish building crisis and its effect in the gypsum quarry production (1998–2012). Resour. Policy 38, 123–129 (2013).

Zhao, Y., Zhang, P., Hu, Y. & Huang, L. Effects of re-vegetation on herbaceous species composition and biological soil crusts development in a coal mine dumping site. Environ. Manage. 57, 298–307 (2016).

Chiquoine, L. P., Abella, S. R. & Bowker, M. A. Rapidly restoring biological soil crusts and ecosystem functions in a severely disturbed desert ecosystem. Ecol. Appl. 26, 1260–1272 (2016).

Belnap, J. Recovery rates of cryptobiotic crusts: inoculant use and assessment methods. Gt. Basin Nat. 53, 89–95 (1993).

Maestre, F. T. et al. Watering, fertilization, and slurry inoculation promote recovery of biological crust function in degraded soils. Microb. Ecol. 52, 365–377 (2006).

Bowker, M., Johnson, N. C., Belnap, J. & Koch, G. W. Short-term monitoring of aridland lichen cover and biomass using photography and fatty acids. J. Arid Environ. 72, 869–878 (2008).

Belnap, J. & Gillette, D. Vulnerability of desert biological soil crusts to wind erosion: the influences of crust development, soil texture, and disturbance. J. Arid Environ. 39, 133–142 (1998).

Scheidegger, C., Frey, B. & Zoller, S. Transplantation of symbiotic propagules and thallus fragments: Methods for the conservation of threatened epiphytic lichen populations. Mitteilungen der Eidgenössischen Forschungsanstalt für Wald, Schnee und Landschaft 70, 41–62 (1995).

Scheidegger, C. & Werth, S. Conservation strategies for lichens: insights from population biology. Fungal Biol. Rev. 23, 55–66 (2009).

Eldridge, D. J. Dispersal of microphytes by water erosion in an Australian semiarid woodland. Lichenol. 28, 97–100 (1996).

Belnap, J. & Gillette, D. A. Disturbance of biological soil crusts: Impacts on potential wind erodibility of sandy desert soils in southeastern Utah. L. Degrad. Dev. 8, 355–362 (1997).

Armstrong, R. A. Field experiments on the dispersal, establishment and colonization of lichens on a slate rock surface. Environ. Exp. Bot. 21, 115–120 (1981).

Smith, P. L. Lichen translocation with reference to species conservation and habitat restoration. Symbiosis 62, 17–28 (2014).

Aldaya, F., Vera, J. A. & Fontbote, J. M. Mapa geológico de España. E. 1:200.000. Granada-Málaga. (IGME. Publicaciones. Ministerio de Industria y Energía, 1980).

Aguilar, J. et al. In Proyecto LUCDEME, Mapa de suelos (ICONA. Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, Madrid, 1992).

IUSS Working Group WRB. World reference base for soil resources 2014, update 2015. International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps. World Soil Resources Reports No. 106 (2015). doi: 10.1017/S0014479706394902

European Commission. Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora. L 206, 7–49 (1992).

Brodo, I. M., Sharnoff, S. D. & Sharnoff, S. Lichens of North America. (Yale University Press, 2001).

Gutiérrez, L. & Casares, M. Flora liquénica de los yesos miocénicos de la provincia de Almería (España). Candollea 49, 343–359 (1994).

Lumbsch, H. T. The identity of Diploschistes gypsaceus . Lichenologist 20, 19–24 (1988).

Ibarz, N. Primera experiencia de restauración de la costra liquénica en ambientes semiáridos. Master thesis (unpublished). Universidad de Granada (2012).

Hafellner, J. & Casares-Porcel, M. Lichenicolous fungi invading lichens on gypsum soils in southern Spain. Herzogia 16, 123–133 (2003).

Llimona, X. Las comunidades de líquenes de los yesos de España. PhD Thesis. (Secretariado de Publicaciones, Intercambio Científico y Extensión Universitaria. Universidad de Barcelona 1974).

Ballesteros, M. et al. Central role of bedding materials for gypsum-quarry restoration: An experimental planting of gypsophile species. Ecol. Eng. 70, 470–476 (2014).

Ballesteros, M. et al. Vegetation recovery of gypsum quarries: Short-term sowing response to different soil treatments. Appl. Veg. Sci. 15, 187–197 (2012).

Fernández-Gálvez, J., Barahona, E. & Mingorance, M. Measurement of infiltration in small field plots by a portable rainfall simulator: Application to trace-element mobility. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 191, 257–264 (2008).

Sancho, L. G., Belnap, J., Colesie, C., Raggio, J. & Weber, B. In Biological Soil Crusts: An Organizing Principle in Drylands (eds Weber, B., Büdel, B. & Belnap, J. ) 287–304, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-30214-0 (Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 2016).

Schroeter, B., Green, T. G. a, Seppelt, R. D. & Kappen, L. Monitoring photosynthetic activity of crustose lichens using a PAM-2000 fluorescence system. Oecologia 92, 457–462 (1992).

Maestre, F. T. & Cortina, J. Small-scale spatial variation in CO2 in soil CO2 efflux in a Mediterranean semiarid steppe. Appl. Soil Ecol. 23, 199–209 (2003).

Castillo-Monroy, A. P., Maestre, F. T., Rey, A., Soliveres, S. & García-Palacios, P. Biological soil crust microsites are the main contributor to soil respiration in a semiarid ecosystem. Ecosystems 14, 835–847 (2011).

Maphangwa, K. W., Musil, C. F., Raitt, L. & Zedda, L. Experimental climate warming decreases photosynthetic efficiency of lichens in an arid South African ecosystem. Oecologia 169, 257–268 (2012).

Malaspina, P., Giordani, P., Faimali, M., Garaventa, F. & Modenesi, P. Assessing photosynthetic biomarkers in lichen transplants exposed under different light regimes. Ecol. Indic. 43, 126–131 (2014).

Maxwell, K. & Johnson, G. N. Chlorophyll fluorescence - a practical guide. J. Exp. Bot. 51, 659–668 (2000).

Therneau, T. M. A Package for survival analysis in S. at http://cran.r-project.org/package=survival (2015).

Therneau, T. M. Coxme: Mixed effects Cox models. at https://cran.r-project.org/package=coxme (2015).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URLhttp://www.R-project.org/ at https://www.r-project.org/ (2015).

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Hothorn, T., Bretz, F. & Westfall, P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometrical J. 50, 346–363 (2008).

Belnap, J. In Biological Soil Crusts: Structure, Function, and Management (eds Belnap, J. & Lange, O. L. ) 150, 339–347 (Springer-Verlag, 2003).

Cerdà, A. & García-Fayos, P. The influence of slope angle on sediment, water and seed losses on badland landscapes. Geomorphology 18, 77–90 (1997).

Wild, H. The natural vegetation of gypsum bearing soils in south central Africa. Kirkia 9, 279–292 (1974).

Murchie, E. H. & Lawson, T. Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis: A guide to good practice and understanding some new applications. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3983–3998 (2013).

Pintado, A., Sancho, L. G., Green, T. G. A., Blanquer, J. M. & Lázaro, R. Functional ecology of the biological soil crust in semiarid SE Spain: sun and shade populations of Diploschistes diacapsis (Ach.) Lumbsch. Lichenol. 37, 425–432 (2005).

Martínez, I. et al. Small-scale patterns of abundance of mosses and lichens forming biological soil crusts in two semi-arid gypsum environments. Aust. J. Bot. 54, 339–348 (2006).

Concostrina-Zubiri, L., Martínez, I., Rabasa, S. G. & Escudero, A. The influence of environmental factors on biological soil crust: From a community perspective to a species level approach. J. Veg. Sci. 25, 503–513 (2014).

Martínez, J. J. et al. A special habitat for bryophytes and lichens in the arid zones of Spain. Lindbergia 19, 116–121 (1994).

Maestre, F. T., Martínez, I., Escolar, C. & Escudero, A. On the relationship between abiotic stress and co-occurrence patterns: an assessment at the community level using soil lichen communities and multiple stress gradients. Oikos 118, 1015–1022 (2009).

Davidson, D. W., Bowker, M., George, D., Phillips, S. & Belnap, J. Treatment effects on the performance of nitrogen-fixing lichens in disturbed crusts of the Colorado Plateau. Ecol. Appl. 12, 1391–1405 (2002).

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the Regional Government of Andalusia (Junta de Andalucía, Proyectos de Excelencia, P11-RNM-7061) and KNAUF GmbH Branch Spain (Project 3092-00/01/02, Fundación UGR-Empresa). M. Ballesteros holds a research grant from Junta de Andalucía (P11-RNM-7061). We are grateful to Ana Foronda, Helena García-Robles, Nuria Ibarz, Raquel Aguilera, Tommaso Porro and Marina Quesada for their collaboration to this research. We also thank Francisco Martín Peinado and the Department of Soil Science at the University of Granada for assistance with rain-simulations. We thank Ana García-Nogales, and to Lindsay Chiquoine, Scott Abella and Matthew Bowker for providing information that helped to improve this paper. We also would like to thank David Nesbitt for linguistic advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., M.B. and M.C. conceived and designed the study. M.B., J.A. and E.M.C. undertook the experiments. M.B. conducted the analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ballesteros, M., Ayerbe, J., Casares, M. et al. Successful lichen translocation on disturbed gypsum areas: A test with adhesives to promote the recovery of biological soil crusts. Sci Rep 7, 45606 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45606

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45606

This article is cited by

-

Artificial biocrust establishment on materials of potash tailings piles along a salinity gradient

Journal of Applied Phycology (2022)

-

Symbiotic microalgal diversity within lichenicolous lichens and crustose hosts on Iberian Peninsula gypsum biocrusts

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Assessing the influence of soil abiotic and biotic factors on Nostoc commune inoculation success

Plant and Soil (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.