Abstract

In this paper, we use a robust inversion algorithm, which we have tested in many regional studies, to obtain the first global model of Curie-point depth (GCDM) from magnetic anomaly inversion based on fractal magnetization. Statistically, the oceanic Curie depth mean is smaller than the continental one, but continental Curie depths are almost bimodal, showing shallow Curie points in some old cratons. Oceanic Curie depths show modifications by hydrothermal circulations in young oceanic lithosphere and thermal perturbations in old oceanic lithosphere. Oceanic Curie depths also show strong dependence on the spreading rate along active spreading centers. Curie depths and heat flow are correlated, following optimal theoretical curves of average thermal conductivities K = ~2.0 W(m°C)−1 for the ocean and K = ~2.5 W(m°C)−1 for the continent. The calculated heat flow from Curie depths and large-interval gridding of measured heat flow all indicate that the global heat flow average is about 70.0 mW/m2, leading to a global heat loss ranging from ~34.6 to 36.6 TW.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Our planet Earth is under constant cooling and differentiation since its origin. Its current thermal state and heat loss can be estimated from surface heat flow measurements1,2,3,4,5,6. However, heat flow estimates have evident drawbacks; they are often measured at sparsely and irregularly distributed sites, and they are strongly affected by shallow hydrothermal circulation and therefore are limited in inferring deep thermal structure of the lithosphere. These uncertainties put quite different estimates of global heat loss. In one early study1, and in some recent calibrations minimizing the hydrothermal effects3,4, the global heat loss was estimated at about 40–47 TW (or 4.4–4.7 × 1013 W). Other reappraisals of global heat flow database, however, concluded that global conductive heat loss falls in the range from 29 to 34 TW2,5,6. The differences between these estimates vary considerably.

An alternate and independent method of studying deep thermal structure and global heat loss is by detecting Curie depths from inversion of surface total field magnetic anomalies7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Global coverage of magnetic anomalies is being constantly improved in recent years15,16, and this allows it possible to map the global Curie isotherm in high-resolution, assuming that the Curie-point temperature is constant globally around 550 °C17,18 and that lateral compositional variations exert neglectable influence on the Curie temperature.

There are several different technical schemes of Curie depth inversion from magnetic anomalies, and even for the same method the selected inversion parameters can also vary among scientists7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Furthermore, previous studies focus only on a particular region of the Earth. These facts render it impossible the global comparison of Curie depth results.

In early regional studies, we have successfully automated the centroid method based on radially-averaged amplitude spectrum to obtain high-resolution Curie depths9,10,11. This saves considerably the computational time. Now we can naturally apply this algorithm to the Earth Magnetic Anomaly Grid of 2-arc-minute resolution (EMAG2, http://geomag.org/)16 to obtain the first global reference model of Curie-point depths (GCDM).

Implementation of the Algorithm

The Earth’s surface from −75° to 75° latitudes is divided into 72 zones, and the two polar zones are treated separately. Within each zone, we transform the magnetic data from geographical coordinate to Cartesian coordinate, before gridding the data in a constant 2.6 km interval using the minimum curvature method, which iteratively solves a set of differential equations to minimize the total second horizontal derivative and honor input data19. We then estimate Curie depths using three different window sizes, 98.8 × 98.8 km2, 195.0 × 195.0 km2, and 296.4 × 296.4 km2. The size of 296.4 × 296.4 km2 is large enough to capture the deepest Curie depths around 50 km, and is larger than in most existing applications of the algorithm. The moving steps for these three window sizes are 49.4 km, 97.5 km, and 98.8 km, respectively. As did before20, we take the average of Curie depths from the three windows as the final Curie depth model. Taken to be constant at 3, the scaling factor of 3D fractal magnetic sources, is defined by

is defined by , in which

, in which  is the 3D power spectrum of the magnetization, kx, ky, and kz are wavenumbers in x, y, and z directions, respectively, and their Euclidean norm

is the 3D power spectrum of the magnetization, kx, ky, and kz are wavenumbers in x, y, and z directions, respectively, and their Euclidean norm

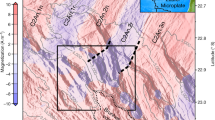

The datum altitude (4 km) of the EMAG2 is subtracted from the estimated Curie depths to be in reference to the geoid (Fig. 1).

White lines mark the major plate boundaries32. Map is generated using the USGS potential field software29,30 and software GMT version 5.2.1 (http://gmt.soest.hawaii.edu/)31.

We applied the standard fast Fourier transform scheme in estimating spectra, but with careful consideration and treatment of boundary effects and short-wavelength tails21. We use the wavenumber band of ~0.005–0.03 1/km for estimating the centroid depths, not just the first slope for stability reasons. It is true that same spectral wavenumber range is not applicable for every window. Our algorithm can judge automatically if the first (smallest wavenumber) point is smaller than the second in the spectra and, if so, does not account this point in the calculation, because theoretically this cannot happen11. In each window, we select the best depth in the least-squares sense.

Our efforts in deriving the first global reference model of Curie depth from magnetic anomalies give us a total number of 516,772 raw Curie depth estimates using the three different window sizes. Different window sizes emphasize different scales of Curie depth variations, but their average, as the final reference model, reduces random noises and improves the resolution model data is available in the supplementary Information. The final spatial resolution of the Curie depth model should be smaller than the smallest moving step, which is 49.4 km. The gridding resolution of our Curie depth model is 10 minutes.

The Global Curie Depth Model (GCDM)

Oceanic domain

Our global Curie depth model (GCDM) shows evident shallowing along mid-ocean ridges, particularly in the Indian, north Atlantic, and Arctic Oceans (Fig. 1). This reflects the active magmatism and upwelling of the hot asthenosphere. GCDM confirms the early results in the north Atlantic11, that in the background of increasing Curie depths with oceanic crustal ages22, anomalous off-ridge upwelling and oscillations in Curie isotherm are observed in all major sea basins, and in most cases, they are associated with small-scale convection or hotspots. For example, the Hawaii seamount trail, the Bermuda Rise, and the Cape Verde Islands all show small Curie depths.

In both the Pacific and Atlantic, large-scale upwells in Curie points are observed in the age range from ~100 to 150 Ma (Fig. 1). By plotting all Curie depth estimates against oceanic crustal ages, we found that this large-scale Curie depth anomaly persists globally (Fig. 2). Assuming an average lithospheric thermal diffusivity κ of 0.319 mm2/s (or 10.06 km2/Ma), observed average Curie depths are larger than predicted from the half-space cooling model for ages <~30 Ma, but are smaller for older crustal ages. This implies that, near the mid-ocean ridges, temperatures are lower than that from the model prediction, probably due to stronger hydrothermal activities, but deep thermal perturbations exist in older lithospheres, particularly in the age range of ~100–150 Ma.

The equation is based on the half-space cooling model assuming an average thermal diffusivity κ of 0.319 mm2/s or 10.06 km2/Ma11.

We find that Curie depths within the two 1 Ma isochrons of active ridges are strongly dependent on the spreading rate (Rr) of Müller et al.22. Ultra-slow spreading ridges (Rr < 4 mm/yr) show large Curie depths averaged at ~17.5 km (Fig. 3). However, the average Curie depth decreases abruptly at slightly higher rates, and then with increasing spreading rates from about 4 to 45 mm/yr (slow to medium spreading rate), the average Curie depth increases linearly, from ~12 to ~18 km. Along fast spreading ridges, average Curie depths decrease very slowly with rates and keep almost constant at ~17.7 km. Likewise along super-fast ridges, average Curie depths also decrease very slowly with spreading rates, but keep at a slightly smaller constant at ~15.2 km and with a narrower distribution. If the fractal scaling factors of magnetization are not dependent on the spreading rate and the Curie temperatures are constant, this overall complex dependence of Curie depths on the spreading rate indicate that the near-ridge thermal structures vary considerably with spreading rate.

The following hypothesis may be perceived to interpret these observations:

- a

For ultra-slow spreading ridge, the magma chamber may be deep seated or may not even exist, and slow mantle exhumation and sufficient cooling lead to large Curie depths.

- b

After the threshold of ~4 mm/yr, decompressive magmatism starts to prevail, and magma chamber form at shallow depth. With increasing spreading rate, decompressive partial melting could occur at progressively larger depths, and the crustal thickening from intensified magmatism can also result in deepening in Curie points. Increasing spreading rate may also trigger stronger hydrothermal circulation, which lowers down the temperature.

- c

Along both fast (45 < Rr < 95 mm/yr) and super-fast spreading centers (Rr > 95 mm/yr), their almost constant average Curie depths suggest that the spreading rate no longer exerts significant role on the thermal structure of the ridge within these respective rate ranges. But the apparent reduction in the average Curie depth around the spreading rate of 95 mm/yr indicates that thermal gradients increase again along super-fast ridges, to be similar to those at slow to medium spreading rate of 25 mm/yr. Super-fast ridges have the most active magmatism that can induce relatively shallower Curie depths.

Continental domain

The majority of the largest Curie depths are found on the continents, most noticeably South America, Africa, and Indian Shield (Fig. 1). However, small Curie depths are also found within some old and stable cratons, such as the Northern China, Siberia, and North America, where large Curie depths are expected from their old ages. This may reflect that reactivation of these old continental cratons has induced thermal perturbations at depth. North China craton, for example, may have been reactivated by the subduction of the Pacific Plate23. The zone of small Curie depths along the western margin of America is also caused by active subductions and related arc magmatism and extension. In southern Africa, a large patch of shallow Curie points could be induced by hot spot magmatism, so is the noticeable Curie depth anomaly associated with the large intraplate hot spot Ahaggar Swell in northern Africa.

Oceanic Curie depths show a good normal distribution with a smaller mean of 20.18 km and a smaller standard deviation than continental Curie depths (Fig. 4). By fitting continental Curie depth distribution with a mixture of two normal distributions, we find that the distribution is nearly bimodal (Fig. 4), which shows a first peak depth of 22.43 km, but a minor second peak occurs around 32.76 km, giving a tail of large Curie depths.

Distributions of Curie depths from continents (a) and oceans (b). Continental distribution can be fitted with a mixture of two normal distributions (red curve). Based on the maximum likelihood optimization, the mixing percentage (p) is 0.75 for the first normal distribution with a mean (mu1) of 22.43 km and a standard deviation (std1) of 5.47 km, and the second normal distribution has a mean (mu2) of 32.76 km and a standard deviation (std2) of 4.24 km. Oceanic distribution can be best fitted with a single normal distribution (red curve) with a mean (mu) of 20.18 km and a standard deviation (std) of 4.78 km.

Estimates of global heat loss

Previous estimates of global heat loss based on surface heat flow range widely from ~29 TW to 47 TW1,2,3,4,5,6. We further exam this problem with reference to our global Curie depth model.

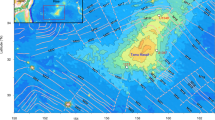

Global heat flow average

Surface heat flow measures the heat loss at the surface of the earth; it could be modulated by hydrothermal circulation or sedimentary cover, but if evenly and densely distributed, its global average quantifies the global heat loss. Large-interval gridding also reduces local measurement biases in heat flow11,20, and hence increases the reliability of interpretation. Our heat flow model, based on a constant 1° interval gridding of all the raw data from the International Heat Flow Commission Database (http://www.heatflow.und.edu/; last updated in January 2011), captures the characteristics of main tectonic features (Fig. 5). Averaging of heat flow values is based on block averaging of (x, y, z) data by L2 norm. We estimate a mean position and heat flow value for every non-empty block in each 1° × 1° grid region to avoid aliasing short wavelengths. We then apply a constant 1° interval gridding of the averaged heat flow using the minimum curvature algorithm with a tension factor of 0.5. Histograms show that gridded heat flow reduces the number of extremely low and high heat flow values caused by hydrothermal process, and retains the original statistical mean (Fig. 6a,b). At the 5% significance level, the Kolmogorov Smirnov statistical test rejected the null hypothesis that the raw and gridded heat flow are from the same continuous distribution (Fig. 6c).

White lines mark the major plate boundaries32. Map is generated using the software GMT version 5.2.1 (http://gmt.soest.hawaii.edu/)31.

Distributions of global heat flow measurements before (a) and after gridding (b). We performed a Kolmogorov Smirnov statistical test to compare the two distributions (c). At the 5% significance level, the test rejected the null hypothesis that the raw and gridded heat flow are from the same continuous distribution.

If we interpolate all the raw heat flow data in a constant 100 km interval, using the minimum curvature algorithm with a tension factor of 0.5, the global heat flow average is 67.8 mW/m2. Alternatively, we interpolate the same data set in a constant 1° interval (Fig. 5), and then resample the grid in a constant 10 minute interval. Then in each 1° × 1° quadrangle we estimate the average of the gridded heat flow, and the global mean from these quadrangles is 68.3 mW/m2. These values are substantially smaller than some of the recent estimates (e.g., 91.6 mW/m2)24.

Global correlation between heat flow and Curie depth

Previous regional studies have shown that heat flow and Curie depth are correlated, following a theoretical thermal conduction relationship10,11. By comparing the Curie depth map (Fig. 1) with heat flow map (Fig. 5), we observe that this correlation should hold for the global data, particularly in active tectonic areas such as mid-ocean ridges and subduction zones. In old and stable continental cratons, surface heat flow may deviate from deep thermal structures due to their long evolutional histories and late-stage thermal perturbations. In thick continental lithosphere, there may be long delays between changes in asthenosphere temperature and measurable effects arriving at the surface25,26. Shallow radioactive contribution to surface heat flow is also larger in the continental domains.

Figure 7 Shows a large scattering in the global correlation between heat flow and Curie depth; this is expected since there are diverse geological units and local structures. Nevertheless, good correlations between heat flow and Curie depth can be observed, i.e., high heat flow measurements tend to correlate with small Curie depths, and vice versa. It is seen that most continental points are clustered in the vicinity of the continental theoretical curve with an average thermal conductivity K of ~2.5 W(m°C)−1, and most oceanic data can be best fitted with the oceanic theoretical curve of an average K = ~2.0 W(m°C)−1. These conductivities are compatible with those of granite and basalt27,28.

Global correlation between heat flow and Curie depths for (a) continental domain and (b) oceanic domain, respectively. In the equation, Qs is the surface heat flow, Tc is the Curie temperature at the Curie depth Zb, T0 is the temperature at the surface elevation Zs, K is the average thermal conductivity of the magnetic layer, H0 is the heat production rate at the surface, and hr is the characteristic drop-off of heat production. For oceanic lithosphere, we assume H0 = 1.37 μW/m3, hr = 5.0 km, Tc = 550 °C, T0 = 5 °C, and Zs = 4 km. For continents, we take H0 = 2.0 μW/m3, hr = 10.0 km, and Zs = −1 km to account for the larger radioactive contribution23. The yellow dashed line marks the global heat flow average estimated in this paper.

Global heat loss

The Earth is divided into 360 × 180 bins of 1° × 1° in size. The exact surface area (Ai) of these latitude-longitude quadrangle bins are calculated assuming a spherical ellipsoid. Calculated heat flow data from Curie depths are gridded in a 10 minute interval. The surface heat flow measurements are interpolated using a constant 1° interval and the grid is also resampled in a 10 minute interval. These data are then averaged, respectively, within each 1° × 1° latitude-longitude quadrangle (Qsi). Quadrangles without heat flow measurements or Curie depth constraints are assumed to take the global average of heat flow. The total heat loss (Thl) is then calculated by

We find that the measured global heat loss is 3.46 × 1013 W (or 34.6 TW) based on our interpolated heat flow. Calculated conductive heat flow from Curie depths using an average continental thermal conductivity k = 2.5 W(m°C)−1 and an oceanic average k = 2.0 W(m°C)−1, is averaged at 72.125 mW/m2. Here the radioactive heat contribution is included in the estimation. The global heat loss hereby obtained is 3.66 × 1013 W (or 36.6 TW). These values are much lower than some of the early estimates3, but slightly larger than some others2,5,6.

Conclusions

Our global Curie depth model (GCDM) shows that oceanic Curie depths increase with crustal ages, but deviate from the half-space cooling model in both young and old oceanic lithospheres. Measured Curie depths are larger than the model predictions in young oceanic lithosphere of age <~30 Ma, but are smaller in older lithospheres. In particular, there is a significant decrease of Curie depths for crustal ages between ~100 and 150 Ma, noticeable in both Atlantic and Pacific. These deviations reflect strong hydrothermal circulations in young oceanic lithospheres and thermal perturbations in aged oceanic lithospheres.

Along active mid-ocean ridges, our study shows that Curie depths are strongly dependent on the spreading rate. There is a unique Curie depth distribution for each single spreading-rate type (i.e., ultra-slow, slow, medium, fast, and super-fast ridges), indicating strong coupling between spreading rate and seafloor-spreading mechanisms, thermal structures, and hydrothermal activities.

Continental domains have the largest Curie depths, but also show nearly a bimodal distribution; small Curie depths are found in some of old continental cratons, indicating that deep thermal reactivations caused inconsistencies between Curie depth and surface heat flow.

Despite a large scatter of points, global correlations between Curie depth and gridded surface heat flow in 1° interval follow theoretical curves of an average thermal conductivity of K = 2.0 W(m°C)−1 for the oceanic data and an continental average K = 2.5 W(m°C)−1. With these optimal conductivities, the calculated global heat flow average is 72.125 mW/m2. This estimate is close to measured global heat flow average from direct large-interval gridding of raw heat flow data, which is about 68.0 mW/m2. We propose that the global heat flow average is around 70.0 mW/m2 and the global heat loss ranges from ~34.6 to 36.6 TW.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, C.-F. et al. A global reference model of Curie-point depths based on EMAG2. Sci. Rep. 7, 45129; doi: 10.1038/srep45129 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Pollack, H. N., Hurter, S. J. & Johnson, J. R. Heat flow from the Earth’s interior: analysis of the global data set. Reviews of Geophysics 31, 267–280 (1993).

Hofmeister, A. M. & Criss, R. E. Earth’s heat flux revised and linked to chemistry. Tectonophysics 395, 159–177 (2005).

Hasterok, D., Chapman, D. S. & Davis, E. E. Oceanic heat flow: Implications for global heat loss. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 311, 386–395 (2011).

Hasterok, D. Global patterns and vigor of ventilated hydrothermal circulation through young seafloor. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 380, 12–20 (2013).

Hamza, V. M., Cardoso, R. R. & Ponte Neto, C. F. Spherical harmonic analysis of earth’s conductive heat flow. Int. J. Earth Sci. 97, 205–226 (2008).

Hamza, V. M., Cardoso, R. R. & Alexandrino, C. H. A magma accretion model for the formation of oceanic lithosphere: implications for global heat loss. Int. J. Geophys., doi: 10.1155/2010/146496 (2010).

Blakely, R. J., Potential Theory in Gravity and Magnetic Applications. Cambridge University Press, 1–464 (1995).

Tanaka, A., Okubo, Y. & Matsubayashi, O. Curie point depth based on spectrum analysis of the magnetic anomaly data in East and Southeast Asia. Tectonophysics 306, 461–470 (1999).

Li, C.-F., Chen, B. & Zhou, Z. Deep crustal structures of eastern China and adjacent seas revealed by magnetic data. Sci. China (Series D) 52, 984–993 (2009).

Li, C.-F. An integrated geodynamic model of the Nankai subduction zone and neighboring regions from geophysical inversion and modeling. J. Geodynamics 51, 64–80 (2011).

Li, C.-F., Wang, J., Lin, J. & Wang, T. Thermal evolution of the North Atlantic lithosphere: New constraints from magnetic anomaly inversion with a fractal magnetization model. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 5078–5105 (2013).

Ravat, D., Morgan, P. & Lowry, A. Geotherms from the temperature-depth–constrained solutions of 1-D steady-state heat-flow equation. Geosphere 12, doi: 10.1130/GES01235.1 (2016).

Salem, A. et al. Depth to Curie temperature across the central Red Sea from magnetic data using the de-fractal method. Tectonophysics 624–625, 75–86 (2014).

Bansal, A. R., Gabriel, G., Dimri, V. P. & Krawczyk, C. M. Estimation of depth to the bottom of magnetic sources by a modified centroid method for fractal distribution of sources: an application to aeromagnetic data in Germany. Geophysics 76, L11–L22 (2011).

Hemant, K., Thébault, E., Mandea, M. Ravat, D. & Maus, S. Magnetic anomaly map of the world: merging satellite, airborne, marine and ground-based magnetic data sets. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 260, 56–71 (2007).

Maus, S. et al. EMAG2: A 2-arc-minute resolution Earth Magnetic Anomaly Grid compiled from satellite, airborne and marine magnetic measurements. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 10, Q08005, doi: 10.1029/2009GC002471 (2009).

Mayhew, M. A., Application of satellite magnetic anomaly data to Curie isotherm mapping. J. Geophys. Res. 87, 4846–4854 (1982).

Tselentis, G.-A. An attempt to define Curie point depths in Greece from aeromagnetic and heat flow data. Pure Appl. Geophys. 136, 87–101 (1991).

Briggs, I. C. Machine contouring using minimum curvature. Geophysics 39, 39–48 (1974).

Li, C.-F. & Wang, J. Variations in Moho and Curie depths and heat flow in Eastern and Southeastern Asia. Mar. Geophys. Res. 37, 1–20 (2016).

Cordell, L. & Grauch, V. J. S. Reconciliation of the discrete and integral Fourier transforms. Geophysics 47, 237–243 (1982).

Müller, R. D., Sdrolias, M. Gaina, C. & Roest, W. R. Age, spreading rates, and spreading asymmetry of the world’s ocean crust. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q04006, doi: 10.1029/2007GC001743 (2008).

Gao, S. et al. Recycling lower continental crust in the North China craton. Nature 432, 892–897 (2004).

Davies, J. & Davies, D. Earth’s surface heat flux. Solid Earth 1, 5–24 (2010).

Korenaga, J. How does small-scale convection manifest in surface heat flux? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 287, 329–332 (2009).

Foulger, G. R. Are ‘hot spots’ hot spots? J. Geodynamics 58, 1–28 (2012).

Turcotte, D. L. & Schubert, G. Geodynamics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 456 (2002).

Whittington, A. G., Hofmeister, A. M. & Nabelek, P. I. Temperature-dependent thermal diffusivity of the Earth’s crust and implications for magmatism. Nature 458, 319–321 (2009).

Cordell, L., Phillips, J. D. & Godson, R. H. USGS potential-field geophysical software for PC and compatible microcomputers. The Leading Edge 12, 290 (1993).

Phillips, J. D. Potential-Field Geophysical Software for the PC, version 2.2. U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report, 97–725 (1997).

Wessel, P., W. H. F. Smith, R. Scharroo, J. F. Luis & F. Wobbe, Generic Mapping Tools: Improved version released. EOS Trans. AGU, 94, 409–410 (2013).

DeMets, C., Gordon, R. G., Argus, D. F. & Stein, S. Current plate motions. Geophys. J. Int. 101, 425–478 (1990).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by National Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 91428309 and 91028007). We thank Dhananjay Ravat and Yaoling Niu for discussions. We also thank two anonymous reviewers who provided in-depth reviews and suggestions for improving this paper. Data processing and mapping are supported by the USGS potential field software, and by GMT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-F. Li improved the algorithm, wrote the software, processed and interpreted the data, prepared figures, and wrote the main manuscript text. Y. Lu processed the data in the two polar regions. J. Wang helped in the data processing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, CF., Lu, Y. & Wang, J. A global reference model of Curie-point depths based on EMAG2. Sci Rep 7, 45129 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45129

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45129

This article is cited by

-

Subduction thermal regime, petrological metamorphism and seismicity under the Mariana arc

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Tectonic boundaries in the South China Sea from aeromagnetic signature

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology (2023)

-

Determination of Curie point depth, heat flow, and geothermal gradient to infer the regional thermal structure beneath the Malay Peninsula using de-fractal method

Arabian Journal of Geosciences (2023)

-

Antarctic geothermal heat flow and its implications for tectonics and ice sheets

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2022)

-

Geothermal energy as a means to decarbonize the energy mix of megacities

Communications Earth & Environment (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.