Abstract

Glasses and single crystals have traditionally been used as optical windows. Recently, there has been a high demand for harder and tougher optical windows that are able to endure severe conditions. Transparent polycrystalline ceramics can fulfill this demand because of their superior mechanical properties. It is known that polycrystalline ceramics with a spinel structure in compositions of MgAl2O4 and aluminum oxynitride (γ-AlON) show high optical transparency. Here we report the synthesis of the hardest transparent spinel ceramic, i.e. polycrystalline cubic silicon nitride (c-Si3N4). This material shows an intrinsic optical transparency over a wide range of wavelengths below its band-gap energy (258 nm) and is categorized as one of the third hardest materials next to diamond and cubic boron nitride (cBN). Since the high temperature metastability of c-Si3N4 in air is superior to those of diamond and cBN, the transparent c-Si3N4 ceramic can potentially be used as a window under extremely severe conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are two known polymorphs of Si3N4 at ambient pressure: α- and β-Si3N4 with hexagonal structures. The latter requires higher temperatures than the former to be synthesized. Practically, most Si3N4 polycrystalline materials are fabricated using α-Si3N4-rich powders and a part of the α-Si3N4 transforms into β-Si3N4 during sintering. In the sintered bodies, the β-Si3N4 grains frequently have elongated shapes with aspect ratios comparable to whiskers that act to toughen the material1. Therefore, the Si3N4 sintered bodies are whisker-reinforced ceramics, which makes this material useful in industry as parts of reciprocating engines, ball bearings, and cutting tools1. In these two phases, silicon atoms are fourfold (tetrahedrally) coordinated by nitrogen atoms.

c-Si3N4, which is often called γ-Si3N4, is stable under high pressure with a spinel structure2. In this structure, two thirds of the silicon atoms are sixfold (octahedrally) coordinated and the rest are fourfold coordinated. The sixfold coordination results in a significantly closer atomic packing and density almost 26% higher than those of the hexagonal phases3. c-Si3N4 is known to be synthesized above ~13 GPa (ref. 3) and has been a candidate as a superhard material4,5 that has a Vickers hardness value above 40 GPa. However, the mechanical properties have not yet been well-constrained.

In this article, we report the synthesis of the bulk polycrystalline form of c-Si3N4 with a grain size of ~150 nm. Using the sintered samples, all the elastic moduli (bulk, shear, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio) were determined; Vickers hardness and fracture toughness were measured. Surprisingly, the obtained bulk polycrystalline form exhibits high optical transparency. Atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) observations were performed to elucidate the mechanism to make this material transparent.

Results

We carried out synthesis runs at three different temperatures of 1600, 1700, and 1800 °C at a fixed pressure of 15.6 GPa. The starting material was commercially available α-Si3N4 powder whose oxygen content is less than 2 wt%. The phases present in the recovered samples were examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements. The sample synthesized at 1600 °C consists mainly of c-Si3N4 but the XRD peaks of α- and β-Si3N4 were also observed. The presence of the hexagonal phases may be explained by a kinetic hindrance of the transformation to c-Si3N4 at relatively lower temperature. This recovered sample was loosely sintered. The samples synthesized at 1700 and 1800 °C consist of a single phase of c-Si3N4 and they are well-sintered. These samples look translucent and transparent, respectively.

We determined a unit cell parameter of c-Si3N4 using an XRD pattern of a sample synthesized at 1800 °C: a = 7.7373 ± 0.0006 Å, which is consistent with that determined in a previous study (a = 7.7381 ± 0.0002 Å)3. The bulk density of this polycrystalline sample was measured to be 4.07 ± 0.08 g/cm3, which is also consistent with a theoretical density3 of 4.022 g/cm3. This result supports the fact that the sample consists of a single phase of c-Si3N4 and indicates that the porosity of this sintered sample is negligibly small. In addition, we measured the bulk chemical composition of this sample. The values we obtained are as follows: Si, 60.1 ± 0.3 wt%; N, 37.1 ± 0.4 wt%; O, 2.5 ± 0.2 wt%; Total, 99.7 ± 0.5 wt%. These values are very close to the calculated values for the stoichiometric Si3N4 (Si, 60.06 wt%; N, 39.94 wt%) and an oxygen-bearing α-phase6, Si11.5N15O0.5 (Si, 59.69 wt%; N, 38.83 wt%; O, 1.48 wt%).

Figure 1a shows a photograph of a recovered sample synthesized at 1800 °C, and it is transparent pale gray. A letter on a ruler behind the sample is clearly seen. Real in-line transmission7 (RIT) was measured as a function of wavelength (Fig. 1b). In these measurements, all light that is scattered at an angle >0.3° is not detected. Therefore, the RIT is a good measure for the visual transparency7. The RIT of this sample is 18–38% for visible light (wavelength of 400–800 nm). We can see the presence of a weak and broad absorption at a wavelength of 500–700 nm, which may cause the pale grey color of this sample. The very low RIT values up to 300 nm can be related to the bandgap energy of 258 nm ( = 4.8 ± 0.2 eV)8.

(a) A photograph of a bulk nanocrystalline form of c-Si3N4 synthesized at 15.6 GPa and 1800 °C. The division of the ruler (this side) is 1 mm. The thickness of the sample is 0.464 mm. (b) Real in-line transmission as a function of wave length. More than ten measurements were performed by rotating the sample around the light axis and by turning the sample over (the polished surfaces were always perpendicular to the light axis) in order to confirm that there is no orientation dependence of the transmission. The red and blue lines show the two representative results.

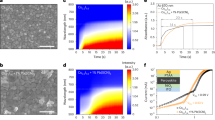

We observed the microstructure of the transparent polycrystalline c-Si3N4. Figure 2a shows an example of the bright-field TEM images. The presence of equigranular texture was observed and the average grain size is 143 ± 59 (one standard deviation) nm. No residual pore and no triple pocket was observed at multi-grain junctions (Fig. 2b), which is consistent with the results of the density measurements. Most of the c-Si3N4 grains have straight grain boundaries and they are almost dislocation-free, which is consistent with the presence of sharp peaks in the XRD patterns (Supplementary Fig. S1). Atomic-resolution STEM observations at grain boundaries between two grains show the presence of disordered/amorphous intergranular films9 (IGFs) with a thickness of less than 1 nm (Fig. 2c). The results of electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) measurements at the IGFs and grain interiors show that oxygen atoms preferentially segregate to the IGFs (Fig. 2d).

(a) a bright-field TEM image of c-Si3N4 synthesized at 15.6 GPa and 1800 °C. The average grain size is 143 ± 59 nm with the maximum grain size of ~400 nm. The inset shows an electron diffraction pattern indicating that the grains are randomly oriented in this polycrystalline material. (b) a low-angle annular dark-field (LAADF) STEM image of a triple junction (the center of the image) showing that no pore and no triple pocket exists. (c) an annular bright-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (ABF-STEM) image at a disordered/amorphous IGF (indicated by the orange arrow) between two grains, where the left grain is viewed along the [110] orientation. (d) EELS spectra at an IGF (top) and in a grain interior (bottom). The decrease of the N-K edge peak and the increase of O-K edge peak were observed at the IGF.

Atomic resolution STEM observations were also performed at multi-grain junctions (Fig. 3a). We observed that the thickness of IGFs near the multi-grain junctions (~1 nm) is similar to that between two grains, which causes the absence of triple pockets. Elemental mappings of silicon, nitrogen, and oxygen (STEM-EDS, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy) confirmed that oxygen atoms segregate to the IGFs and revealed that the IGFs consist of silicon oxynitride (Fig. 3b–d).

(a) An ABF-STEM image of the triple junction area shown in Fig. 2b. The thickness of the IGFs near the triple junction is ~1 nm. No triple pocket exists in the atomic-scale observation. EDS chemical mappings of silicon (b), oxygen (c) and nitrogen (d). The results show that the IGFs consist of silicon oxynitride.

The very thin IGFs and the absence of triple pockets could be the reasons for the optical transparency of the bulk polycrystalline c-Si3N4. Scattering of incident light is caused by the following factors10: (1) optically inhomogeneous materials with secondary phases that have different refractive indices; (2) not isotropic crystals by birefringence. The absence of triple pockets (no second phase) and the cubic spinel structure (MgAl2O4 spinel11 and γ-AlON (ref. 12), which are known as popular transparent ceramics, have the same crystal structure) causes small scattering losses resulting in the optical transparency of bulk polycrystalline c-Si3N4.

Although α- and β-Si3N4 phases are intrinsically transparent because of the wide bandgaps13 (single crystals of α-Si3N4 were reported to be transparent)14, the Si3N4 sintered compacts that consist of α- and β-phases look opaque1. In the case of the sintering at lower pressures (e.g. hot-pressing), sintering aids such as MgO, SiO2, and Al2O3 are required to obtain the toughened and highly densified compacts1. For example, MgO reacts with silicon and oxygen in the system and the magnesium silicate is molten under high temperature; after cooling, it remains mainly in triple pockets as an amorphous phase1. Even in the case of sintered β-Si3N4 ceramics without additives, the presence of amorphous triple pockets was observed15 and their dimensions are several tens to several hundreds of nanometers16. The chemical composition of the β-Si3N4 grains is nearly pure Si3N4 and that of the amorphous triple pockets is SiO2 with a small amount of nitrogen16. Since the β-Si3N4 cannot incorporate the impurities into its structure, the formation of the triple pockets may be inevitable as reservoirs of additives and impurities in the sintered bodies. The refractive index of the amorphous phase in the triple pockets can be different from those of the crystalline phases (α- and β-phase with hexagonal symmetry), which causes scattering of the incident light resulting in opaque sintered bodies.

On the other hand, it has been reported that some polycrystalline α-SiAlONs exhibit optical transparency17. These materials are isostructural with α-Si3N4, in which silicon and nitrogen are partially substituted by aluminum and oxygen (Si3N4-based solid solutions)17. The incorporation of the additives into the structure produces little or no triple pocket, which causes small scattering losses of light resulting in optical transparency. This mechanism may be applied to the case of the transparent c-Si3N4. The absence of triple pockets in this material (Fig. 3a) indicates that at least a part of the oxygen impurities is incorporated into the c-Si3N4 structure.

The composition of the hypothetical oxygen-bearing c-Si3N4 may be inferred by analogy from that of α-Si3N4. It was reported that α-Si3N4 contains oxygen in its crystal structure, which could be explained by nitrogen vacancies with electrical neutrality being obtained by an appropriate number of silicon vacancies or Si3+ species1. The compositions suggested are Si23N30O or Si4+20Si3+4N30O, respectively, which are similar to the compositions of the starting material and the transparent c-Si3N4 ceramic. In addition, aluminum oxynitrides with a spinel structure (γ-AlONs) contain cation vacancies18. For example, in Al23O27N5 spinel, 8 Al3+ occupy all the tetrahedral sites and 15 Al3+ occupy octahedral sites with 1 vacancy18. Thus, the cation vacancy model (Si23N30O) might be preferable for the hypothetical oxygen-bearing c-Si3N4. Actually, our EELS spectrum at grain interior might show the presence of oxygen in the structure (Fig. 2d). The silicon and nitrogen vacancies might cause the pale grey color of this transparent c-Si3N4 (Fig. 1a). Further studies are required to elucidate the mechanism of oxygen incorporation into c-Si3N4 and the resultant optical transparency.

In order to show a potential of the transparent c-Si3N4 ceramic as a hard and tough window, the mechanical properties of this material were measured. Since it is optically transparent, Brillouin scattering was performed to measure longitudinal and transverse wave velocities (VP and VS, respectively). We obtained VP = 12.55 km/s and VS = 7.84 km/s with estimated errors of 0.5%. Then, we can calculate all the elastic moduli at ambient conditions using the theoretical density3 of 4.022 g/cm3: bulk modulus (B), 303.4 ± 4.0 GPa; shear modulus (G), 247.5 ± 1.0 GPa; Young’s modulus (E), 583.8 ± 10.1 GPa; Poisson’s ratio (ν), 0.1793 ± 0.0056. The comparison with previous results5,19,20,21,22 is shown in Table 1.

Vickers indentation tests were carried out at indentation loads between 0.196 and 19.6 N to measure the Vickers hardness (HV) and evaluate the fracture toughness (KIc). Fig. 4a shows the indentation load dependence of HV. The HV decreases with indentation load to an asymptotic value beyond 5 N. We employed HV = 34.9 ± 0.7 GPa at 9.8 N as a representative value of this material. The comparison with previous results4,5 is also shown in this plot. 6-Mar-2017 11:376-Mar-2017 11:376-Mar-2017 11:376-Mar-2017 11:376-Mar-2017 11:376-Mar-2017 11:37 4b shows an indentation load dependence of KIc. The average of all the measured values is 3.5 ± 0.2 MPa·m1/2. The transparent c-Si3N4 is tougher than transparent MgAl2O4 spinel (KIc~1.7 MPa·m1/2)23 and γ-AlON (KIc~2.4 MPa·m1/2)23, and is as tough as polycrystalline alumina, which is a popular structural ceramic in industry. The obtained mechanical properties and comparison with previous results4,5,20,21,22,24,25 are also shown in Table 1.

(a) Indentation load dependence of Vickers (HV) and Knoop hardness (HK) of c-Si3N4. Previous results are shown for comparison (squares). (b) Indentation load dependence of fracture toughness (KIc). The inset shows a micrograph of a representative indentation trace with cracks at an indentation load of 9.8 N (by transmitted light microscopy). Since the sample is optically transparent, we can observe radial-median cracks propagated into the sample. (c) HV vs. shear modulus (G) for hard materials (closed circles). c-Si3N4 is in the group of the third hardest material with B4C and B6O. c-Si3N4 is much harder than MgAl2O4-spinel and γ-AlON. The polycrystalline materials that exhibit optical transparency are shown with stars.

In order to compare the hardness of c-Si3N4 with those of other materials, we have updated a plot proposed by Teter26, HV vs. G (Fig. 4c, the details are shown in supplementary information). c-Si3N4 is as hard as and elastically stiffer than B4C and B6O. These three materials are in the group of the third hardest materials (not superhard materials) next to diamond and cBN.

Discussion

The polycrystalline c-Si3N4 shows intrinsic transparency (Fig. 1b): no strong light absorption at wavelengths below its bandgap energy. Diamond is the hardest material and the synthesis of transparent nano-polycrystalline diamond (NPD) was reported27. NPD shows its characteristic brownish color, which is given by a continuous absorption at wavelengths between 500 and 700 nm. This absorption could be attributed to lattice defects induced by plastic deformation during the synthesis process28. This material also shows strong continuous absorption at wavelengths between 225 nm (band gap energy) and 450 nm, which is attributed to electron transitions from nitrogen (impurity) to the conduction band28. Thus, NPD is transparent, but does not show its intrinsic transparency. Polycrystalline cBN materials have been reported to be translucent29; B4C and B6O materials are opaque. Thus, the polycrystalline c-Si3N4 is nearly color-less and the second hardest ceramic window (Fig. 4c).

The transparent polycrystalline c-Si3N4 can potentially be employed in industry to protect optical sensors and detectors under severe conditions. One of the advantages of this material is an excellent thermal metastability in air24, at least up to 1400 °C, which is superior to that of diamond, cBN, and other hard materials30. On the other hand, one of the limitations of this material for industrial applications is the small size of the bulk material because of synthesis under high pressure above 13 GPa (ref. 3). In this article, we reported the synthesis of the transparent disks with diameter of ~2 mm (Fig. 1a). If one of the world’s largest high-pressure instruments is employed for the synthesis, transparent c-Si3N4 disks with diameter larger than 10 mm can be synthesized31. The centimeter-sized transparent disks can be used in industry as windows for small devices.

Methods

Starting material and the container for synthesis under high pressure and temperature

The starting power was commercially available α-Si3N4 powder (SN-E10, Ube Industries, Ltd., Ube, Japan). According to the product catalog, the proportion of the α-phase is >95 wt%; the oxygen content is <2 wt%.; the specific surface area is 9–13 m2/g. The as-received powder was dried in an oil-free vacuum oven (~8 hPa) at 200 °C for ~12 hours. The dried powder was enclosed in a sample capsule made of a platinum sleeve and disks, which were embedded into an outer MgO sleeve with MgO lids. Before loading the sample, the platinum and MgO parts were heated at 1000 °C for ~10 min. After loading the sample, the assembled sample container was dried again in the vacuum oven at 150 °C for more than 2 hours before the synthesis runs.

Synthesis under high-PT

High-pressure and high-temperature synthesis experiments were performed using a Kawai-type apparatus, installed at DESY, with a Walker-module (mavo press LPR 1000-400/50; Max Voggenreiter GmbH, Mainleus, Germany). The maximum force of this instrument is 1000 tonf. The second stage anvils were tungsten carbide cubes with a truncated edge length of 7 mm. A Cr2O3-doped magnesia octahedron with an edge length of 14 mm was used as the pressure transmitting medium. A cylindrical LaCrO3 furnace (Nikkato Corp., Osaka, Japan) was employed. A sample container made of platinum and MgO was embedded into the furnace. Further details are shown in Supplementary information.

XRD measurements

XRD patterns of the recovered samples were obtained using an X-ray diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (MiniFlex-600; Rigaku, Japan). The measurements were also carried out at the P02.1 in PETRA III, Germany. X-rays monochromatized by a (111) diamond and a (111) silicon crystal in Laue geometry with an energy of ~60 keV were used. The incident beam-size was 300 × 300 μm2. The transmission geometry and a two-dimensional detector (XRD 1621, PerkinElmer) were employed. The sample-to-detector distance (~900 mm) and the detector orthogonality were calibrated using the diffraction pattern for cerium dioxide powder.

Bulk density and chemical composition measurements

Density of a recovered sample was measured with an AccuPyc II 1340 pycnometer, using He gas displacement and mass measurements. Chemical composition of the recovered sample was measured using a scanning electron microscope equipped with an energy-dispersive detector. The accelerating voltage, current, and working distance was 20 kV, 1 nA, and 10 mm, respectively. During the data collection, the electron beam was scanned over the surface of the sample in the area of ~1 μm × ~1 μm. Data aquisition time was 20 s. The standards employed for elemental quantifications were as follows: Si, SiC; N, cBN; O, SiO2. The polished surface of the recovered sample was coated with osmium.

Light transmission measurements

Real in-line transmission of a recovered sample was measured in the wavelength range of 240 and 1600 nm using a double-beam spectrophotometer (SolidSpec-3700DUV, Shimadzu, Japan), installed at NIMS, equipped with an integrating sphere. The diameter of light at the sample is about 0.8 mm and an aperture with diameter of 2 mm was used at the entrance of the integrating sphere. The distance between the sample and the aperture is 550 mm. The top and bottom surfaces of the disk-shape sample were polished using diamond pastes down to 1 μm and the thickness is 0.464 mm.

TEM observations

For conventional BF-TEM and electron diffraction observations were carried out by JEM 2010HC (JEOL Ltd.). For atomic-resolution imaging and spectroscopy, we used an aberration-corrected STEM of ARM 300CF (JEOL Ltd.), installed at University of Tokyo, equipped with a JEOL ETA corrector, a cold field-emission gun, Gatan Quantum ER EELS spectrometer, and a JEOL silicon drift detector for EDX spectrometer. The used illumination semi-angle is 24 mrad and the ABF- and ADF-detector is spanning 12–24 and 80–200 mrad, respectively. We used dual-EELS mode to simultaneously acquire core-loss and zero-loss spectra (the energy dispersion is 0.25 eV per channel) and the energy drift was corrected via post processing. We operated the STEM at 300 kV with typically 20 pA beam current, where no significant beam damage was observed. The grain size of the sample was determined by direct measurement of 100 grains that appear black (satisfying the Bragg condition) in a conventional BF-TEM image32.

Brillouin scattering measurements

Elastic wave velocities were measured using the Brillouin system, installed at University of Bayreuth, employing 532 nm laser light, a multi-pass tandem Fabry-Perot interferometer and an avalanche photodiode for signal detection. Measurements were performed in symmetric forward scattering geometry using a scattering angle of 80°. Spectrum collection times were about 5 minutes at a laser power of 70 mW.

Hardness and fracture toughness measurements

HV was measured using a microhardness indenter (HM-221, Mitsutoyo) installed at DESY. A hard steel standard with 900 HV was used. The holding time under the indentation load is 15 s. HV was calculated using the following equation: HV = 1854.4 P/d2, where P is the applied load (N) and d is the arithmetic mean of the two diagonals (μm) of a Vickers indentation trace. KIc was calculated from the crack length, c, using the following equation: KIc = ξ (E/HV)1/2 (P/c3/2), where E is the Young’s modulus (GPa) and ξ is a calibration constant of 0.016 (ref. 33). Knoop hardness (HK) was measured using the same instrument. The applied load was 0.196–9.8 N with a holding time of 15 s.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Nishiyama, N. et al. Transparent polycrystalline cubic silicon nitride. Sci. Rep. 7, 44755; doi: 10.1038/srep44755 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Riley, F. L. Silicon nitride and related materials. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 83, 245–265 (2000).

Zerr, A. et al. Synthesis of cubic silicon nitride. Nature 400, 340–342 (1999).

Schwarz, M. et al. Spinel-Si3N4: multi-anvil press synthesis and structural refinement. Adv. Mater. 12, 883–887 (2000).

Tanaka, I. et al. Hardness of cubic silicon nitride. J. Mater. Res. 17, 731–733 (2002).

Zerr, A. et al. Elastic moduli and hardness of cubic silicon nitride. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 85, 86–90 (2002).

Terwilliger, G. R. & Lange, F. F. Hot-pressing behavior of Si3N4 . J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 57, 25–29 (1974).

Apetz, R. & von Bruggen, P. B. Transparent alumina: a light-scattering model. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 86, 480–486 (2003).

Boyko, T. D., Hunt, A., Zerr, A. & Moewes, A. Electronic structure of spinel-type nitride compounds Si3N4, Ge3N4, and Sn3N4 with tunable band gaps: application to light emitting diodes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 097402 (2013).

Kleebe, H.-J., Cinibulk, M. K., Cannon, R. M. & Rühle, M. Statistical analysis of the intergranular film thickness in silicon nitride ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 76, 1969–1977 (1993).

Krell, A., Klimke, J. & Hutzler, T. Transparent compact ceramics: inherent physical issues. Opt. Mater. 31, 1144–1150 (2009).

Krell, A., Hutzler, T., Klimke, J. & Potthoff, A. Fine-grained transparent spinel windows by the processing of different nanopowders. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 93, 2656–2666 (2010).

McCauley, J. W. et al. AlON: a brief history of its emergence and evolution. J. Euro. Ceram. Soc. 29, 223–236 (2009).

Xu, Y.-N. & Ching, W. Y. Electronic structure and optical properties of α and β phases of silicon nitride, silicon oxynitride, and with comparison to silicon dioxide. Phys. Rev. B 51, 17378–17389 (1995).

Kijima, K., Setaka, N. & Tanaka, H. Preparation of silicon nitride single crystals by chemical vapor deposition. J. Crystal Growth 24/25, 183–187 (1974).

Tanaka, I., Pezzotti, G., Matsushita, K., Miyamoto, Y. & Okamoto, T. Impurity-enhanced intergranular cavity formation in silicon nitride at high temperatures. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 74, 752–759 (1991).

Gu, H., Cannon, R. M., Seifert, H. J., Hoffmann, M. J. & Tanaka, I. Solubility of Si3N4 in liquid SiO2 . J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 85, 25–32 (2002).

Jones, M. I., Hyuga, H., Hirao, K. & Yamauchi Y. Highly transparent Lu-α-SiAlON. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 87, 714–716 (2004).

McCauley, J. W. A simple model for aluminum oxynitride spinels. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 61, 372–373 (1978).

Soignard, E., Somayazulu, M., Dong, J., Sankey, O. F. & McMillan, P. F. High pressure-high temperature synthesis and elasticity of the cubic nitride spinel γ-Si3N4 . J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 13, 557–563 (2001).

Dong, J., Deslippe, J., Sankey, O. F., Sognard, E. & McMillan, P. F. Theoretical study of the ternary spinel nitride system Si3N4-Ge3N4 . Phys. Rev. B 67, 094104 (2003).

Kocer, C., Hirosaki, N. & Ogata, S. Ab initio calculation of the ideal tensile and shear strength of cubic silicon nitride. Phys. Rev. B 67, 035210 (2003).

He, J. et al. Hardness of cubic spinel Si3N4 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 5571–5573 (2004).

Ramisetty, M., Sastri, S., Kashalikar, U., Goldman L. M. & Nag, N. Transparent polycrystalline cubic spinels protect and defend. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 92(2), 20–25 (2013).

Jiang, J. Z., Kragh, K., Frost, D. J., Ståhl, K. & Lindelov, H. Hardness and thermal stability of cubic silicon nitride. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 13, L515–L520 (2001).

Gao, F., Xu, R. & Liu, K. Origin of hardness of nitride spinel materials. Phys. Rev. B 71, 052103 (2005).

Teter, D. M. Computational alchemy: the search for new superhard materials. MRS Bull. 23, 22–27 (1998).

Irifune, T., Kurio, A., Sakamoto, S., Inoue, T. & Sumiya, H. Ultrahard polycrystalline diamond from graphite. Nature 421, 599–600 (2003)

Sumiya, H. et al. Optical characteristics of nano-polycrystalline diamond synthesized directly from graphite under high pressure and high temperature. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 48, 120206 (2009).

Sei, H., Akaishi, M. & Yamaoka, S. Effect of small amounts of hydrochloric acid on the synthesis of translucent sintered cubic BN. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2, 1160–1163 (1993).

Zerr, A. et al. Recent advances in new hard high-pressure nitrides. Adv. Mater. 18, 2933–2948 (2006).

Irifune, T., Isobe, F. & Shinmei, T. A novel large-volume Kawai-type apparatus and its application to the synthesis of sintered bodies of nano-polycrystalline diamond. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 228, 255–261 (2014).

Irifune, T. et al. Pressure-induced nano-crystallization of silicate garnets from glass. Nat. Commun. 7, 13753 (2016).

Anstis, G. R., Chantikul, P., Lawn, B. R. & Marshall, D. B. A critical evaluation of indentation techniques for measuring fracture toughness: I, direct crack measurements. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 64, 533–538 (1981).

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Hosono, R. Riedel, and I. Tanaka for discussion. We also thank H-P. Liermann and S. Sonntag for technical assistance. We are grateful to W. Drube, H. Franz, C. Schroer, and E. Weckert for encouragement during this study. R. I. and Y. I. acknowledge ‘Research Hub for Nano Characterization’ (University of Tokyo), supported under ‘Nanotechnology Platform’ of MEXT and Core-to-Core Program of JSPS (No. 26630122). This research was supported by JST, PRESTO, New Materials Science and Element Strategy granted to N.N. Part of this research was supported through the project “GeoMaX” funded under the Emmy-Noether Program of the German Science Foundation (MA4534/3-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.N. and T.T. designed the study. R.I. and Y.I. performed TEM observations. H.O. and T.I. performed SEM observations and chemical composition measurements. H.M. and A.K. performed Brillouin scattering measurements. N.N., T.T., E.K., and F.W. performed high pressure synthesis. B-N.K. and H.Y. performed real in-line transmission measurements. A.M. performed density measurements. J.B., E.K., and N.N. performed XRD measurements. N.N., R.I., T.T. and Y.I. wrote the manuscript with contributions from other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Nishiyama, N., Ishikawa, R., Ohfuji, H. et al. Transparent polycrystalline cubic silicon nitride. Sci Rep 7, 44755 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44755

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44755

This article is cited by

-

Microstructural and Mechanical Properties of Cubic Silicon Nitride: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance (2023)

-

Increasing Fracture Toughness and Transmittance of Transparent Ceramics using Functional Low-Thermal Expansion Coatings

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Theoretical predicted high-thermal-conductivity cubic Si3N4 and Ge3N4: promising substrate materials for high-power electronic devices

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.