Abstract

Following corneal epithelium scratches, mouse corneas were infected with the multidrug resistant (MDR) P. aeruginosa strain PA54. 24 hours later, 0% (for control group), 0.01%, 0.05% or 0.1% Chlorin e6 (Ce6), a second generation photosensitizer derived from chlorophyll, was combined with red light, for photodynamic inactivation (PDI). 1 hour or 2 days later, entire mouse eyes were enucleated and homogenized for counting colony forming units (CFU) of P. aeruginosa. For comparison, 0.1% Ce6 mediated PDI was started at 12 hours post infection, and 0.005% methylene blue mediated PDI 24 hours post infection. Clinical scores of corneal manifestation were recorded daily. Compared to the control, CFU 1 hour after PDI started 24 hours post infection in the 0.01% Ce6 and 0.05% Ce6 groups were significantly lower (more than one log10 reduction), the CFU 2 days post PDI higher in the 0.1% Ce6 group, clinical score lower in the 0.1% Ce6 group at 1 day post PDI. These findings suggest that PDI with Ce6 and red light has a transient efficacy in killing MDR-PA in vivo, and repetitive PDI treatments are required to fully resolve the infection. Before its clinical application, the paradoxical bacterial regrowth post PDI has to be further studied.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), a Gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium, is among the most common pathogens of bacterial keratitis1. P. aeruginosa keratitis usually causes a rapidly progressive, suppurative corneal infiltration, ulceration, and finally perforation and blindness2. Infections caused by P. aeruginosa are further complicated by the fact that multidrug resistant (MDR) variants of this species are on the rise worldwide3,4, which are difficult to treat by conventional therapy, the empirical but intensive topical treatment with commonly used ophthalmic antibiotics, such as the fluoroquinolones ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin, the aminoglycosides gentamicin and tobramycin, and the 1st generation cephalosporin cefazolin, respectively5,6. Many risk factors, such as contact lens use, compromised ocular surface and preservative-free lubricant ointment use, can predispose patients to P. aeruginosa keratitis7. P. aeruginosa may also cause keratitis after keratoplasty, which often leads to a very poor outcome8. The development of alternative therapy options to fight this type of infection has become imperative.

Photodynamic inactivation (PDI) is a novel promising antimicrobial strategy against MDR bacteria9,10. It is a photochemical reaction combining light, a photosensitizer, and oxygen to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as singlet oxygen (1O2) and hydroxyl radicals (HO)11. Unlike antibiotics, PDI causes a non-specific bactericidal effect, since ROS can damage various vital bacterial structures, mainly cell wall proteins and membranes12,13.

PDI might be especially applicable for the treatment of infectious keratitis, since the transparency and superficial location of the cornea facilitate the deposition of the photosensitizer and the irradiation process. As early as in the 1970s, some clinical studies already tried to treat viral keratitis with PDI, but these investigations were soon suspended due to severe adverse reactions, such as phototoxic epithelial keratitis and anterior uveitis14,15. In the following decades, only in vitro studies that explored the possibility of PDI to combat clinically important corneal pathogens were reported16,17,18,19,20,21,22. To date, the in vivo use of PDI as antimicrobial therapy is mainly restricted to the treatment of dermatological and dental infections23. In ophthalmology, PDI was rarely used as a treatment option for ocular infections, although another photodynamic therapy procedure, i.e. corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet light, is nowadays commonly applied as a treatment for corneal ectatic diseases24. A small number of clinical case reports indeed suggest that corneal crosslinking might be used as a therapy option for bacterial keratitis25,26,27,28, while other case reports indicated an increase in microbial infections as a complication of this therapy form when treating corneal ectatic diseases29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. To date, only little experimental evidence is provided, whether PDI is a useful option to fight bacterial keratitis. In 2011, Shih et al.39 demonstrated the bactericidal efficiency of a combination of the antibiotic amikacin and PDI with the photosensitizer methylene blue (MB) and red light (λ = 650 nm) in a rabbit model of Mycobacterium fortuitum keratitis. However, they did not assess the impact of PDI as a single treatment. In the same year, El-Laithy et al.40 treated Staphylococcus aureus keratitis in rabbits with the photosensitizer hematoporphyrin and red light (λ = 630 nm). However, they failed to detect a statistically significant impact of this therapy regimen.

In the present study, we evaluated the efficiency of PDI with the photosensitizer Ce6 and red light (λ = 670 nm) as a single therapy option for the treatment of MDR P. aeruginosa keratitis in mice. Previous in vitro studies demonstrated that this photosensitizer/light combination can kill up to 100% of the challenged P. aeruginosa cells41,42,43,44. However, whether such a remarkable bactericidal rate can be achieved in vivo is questionable. Under in vitro conditions, bacteria can be fully mixed with the photosensitizer, and the generated ROS will predominantly damage the bacterial cell components. The in vivo environment is much more complicated. Corneal epithelium and stroma may hinder the diffusion of the photosensitizer towards the bacteria within the infected tissue. ROS can diffuse for only short distance, e.g. less than 50 nm, once they are generated from the activated photosensitizer45. Thus, a substantial proportion of ROS produced by PDI is likely to react with host components, including cellular structures and molecules, and may cause unexpected cascade reactions46.

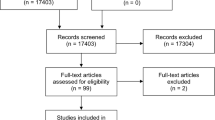

To assess the effect of Ce6 mediated PDI as a single therapy for the treatment of MDR-PA keratitis in mice in vivo, three regimens of PDI were tested (Fig. 1). In all regimen, visible red light (λ = 670 nm) was applied, thereby avoiding the potential genotoxicity induced by ultraviolet light used in corneal crosslinking47.

In regimen I, at 24 h post MDR-PA infection, corneal epithelia were removed from infected mouse eyes using a hockey epithelium removal knife to improve the diffusion of the photosensitizer into the stroma48, before PDI mediated by 0%, 0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% (w/v) Ce6 and red light was applied. Mice were euthanized either 1 h post PDI or 48 h post PDI, the infected eyes enucleated and subsequently homogenized with a manual disperser for CFU determinations as outlined in Material and Methods.

In regimen II, PDI mediated by 0% and 0.1% Ce6 was carried out 12 h post infection on deepithelialized corneas, and mice were euthanized 60 h post PDI for CFU counting. Inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, which are recruited to the cornea due to the P. aeruginosa infection, are essential for controlling the bacterial population. However, an excessive influx and persistence of these inflammatory cells may also lead to corneal destruction2. PDI may interfere with the corneal response to P. aeruginosa unintentionally by killing these inflammatory cells. Of note, Tanaka et al.49 reported that a MB concentration of around 100 μM, when activated with a red light dose of 20 J/cm2, spared neutrophils but killed most of the bacteria under in vitro conditions.

Therefore, in regimen III, we used MB as a reference to investigate whether it causes a similar effect as Ce6. PDI mediated by 0.005% MB was carried out at 24 h post infection. Mice were euthanized 48 h post PDI for CFU counting.

Results

Regimen I (Ce6 mediated PDI at 24 h post infection)

In the first regimen, PA54 infected eyes were treated 24 h post infection by PDI with different concentrations of Ce6 and red light, and bacterial loads were subsequently determined in homogenates of whole eyes enucleated 1 h and 48 h post PDI treatment, respectively, in order to determine the short term and long term effects of PDI on the bacterial loads in the infected eyes (Fig. 2). The CFU values found in the eyes of PA54 infected mice 1 h after PDI are shown in Fig. 2A. Upon PDI the bacterial loads found in mice treated with the 0.01% Ce6 gel (Log10CFU = 5.19 ± 0.75, P = 0.028) and the 0.05% Ce6 gel (Log10CFU = 5.13 ± 0.61, P = 0.015) decreased significantly when compared to the CFU rates found in the eyes of control mice (Log10CFU = 6.21 ± 0.91) treated with the gel-base (0% Ce6) only. CFU of 0.1% Ce6 gel treated mice (Log10CFU = 5.41 ± 0.63) were likewise lower than the CFU of sham treated controls (i.e. 0% Ce6), however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.058).

(A) Log10CFU 1 h after regimen I (chlorin e6 mediated PDI at 24 h post infection), (B) Log10CFU on day 3, of each mouse is displayed as a single dot in the scatter plot, grouped by the concentrations of chlorin e6 (Ce6) used in PDI at hour 24. Mean of Log10CFU of each group is shown as a bar. (A) Log10CFU in 0.01% Ce6 group (*P = 0.028) and 0.05% Ce6 group (*P = 0.015) are significantly lower than the control group treated by 0% Ce6. (B) Log10CFU in 0.1% Ce6 group is significantly higher than the control group treated by 0% Ce6 (*P = 0.011).

A different picture emerged when the bacterial loads of PA54 infected mice were determined 48 h post PDI (Fig. 2B). Here, the bacterial loads in the eyes of mice treated with the 0.1% Ce6 gel (Log10CFU = 7.38 ± 0.22) increased significantly when compared with the CFU rates found in the eyes of the sham treated control group (Log10CFU = 6.95 ± 0.25, P = 0.011). Likewise, CFU rates found in the eyes of the 0.05% Ce6 gel treated group (Log10CFU = 7.19 ± 0.13), and the 0.01% Ce6 gel treated group (Log10CFU = 7.11 ± 0.27) exceeded the CFU values observed in the eyes of the sham-treated control group, however, this was not statistically significant (P = 0.068 and 0.333, respectively).

The course of infection in the eyes of mice challenged with PA54 was additionally monitored by stereo-microscopic determinations and graded as outlined in Materials and Methods. The clinical scores from PA54 infected eyes determined 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h post infection, respectively, are shown in Fig. 3, and representative stereo-microscopic images of PA54 infected eyes over time are given in Fig. 4. Here, significant increases in infection severity were observed for the sham treated group and the 0.01% Ce6 group, when the development of infection symptoms over time within a treatment group were compared. The clinical scores of 0.01% Ce6 gel treated mice increased significantly throughout the observation period (P = 0.026 for 24 h vs. 48 h, and P = 0.026 for 24 h vs. 72 h). Similarly, the clinical scores of sham treated mice increased significantly from 24 to 72 h post infection (P = 0.009). However, such increases in severity of infection over time were neither seen in 0.05% Ce6 nor in 0.1% Ce6 treated mice.

Means with standard deviations are shown. On day 2, clinical scores of 0.1% Ce6 group were significantly lower than the control group treated by 0% Ce6 (*P = 0.015). Clinical scores of 0% Ce6 group increased significantly from hour 24 to day 3 (*P = 0.009). Clinical scores of 0.01% Ce6 group increased significantly from hour 24 to day 2 (*P = 0.026), and from hour 24 to day 3 (*P = 0.026).

Representative corneal manifestations of mice treated by regimen I (chlorin e6 mediated PDI at 24 h post infection), in which PDI was mediated by (A,B,C) 0%, (D,E,F) 0.01%, (G,H,I) 0.05% and (J,K,L) 0.1% chlorin e6 (Ce6). Photos were taken (A,D,G,J) right before infection of P. aeruginosa (hour 0), (B,E,H,K) before PDI (hour 24), and (C,F,I,L) on day 3. (E) A characteristic infiltration ring of P. aeruginosa keratitis (clinical score 3). The corneal suppurative infiltration developed rapidly in all mice, but on day 3, it seemed to be milder in (L) the mouse treated by 0.1% Ce6 mediated PDI (clinical score 3) than the others (clinical score 4).

When the clinical scores for a given time point were compared between groups, in most cases no clear differences in infection symptoms were observed (P ≥ 0.209). The only exception was seen in the 0.1% Ce6 group, in which clinical scores at 48 h post infection (clinical score = 2.3 ± 0.5) were significantly lower than those seen with the sham treated control group (clinical score = 3.5 ± 0.5, P = 0.015). At 72 h post infection (i.e. 48 h post PDI), clinical scores of the 0.1% Ce6 group also displayed lower values (clinical score = 2.8 ± 0.8) than those seen in the control group (clinical score = 3.8 ± 0.4), although this was not statistically significant (P = 0.060).

Regimen II (chlorin e6 mediated PDI at hour 12 post infection)

In the second regimen, PA54 infected eyes were treated 12 h post infection by PDI with 0.1% Ce6 and red light, and bacterial loads were subsequently determined in homogenates of whole eyes enucleated 60 h post PDI treatment (Fig. 5). This regimen was chosen in order to determine whether an earlier PDI treatment time point might prevent an overgrowth of surviving bacteria that was seen at 72 h post infection in regimen I. Interestingly, when PDI with 0.1% Ce6 and red light was applied earlier in infection (i.e. at 12 h post infection), the CFU values observed in the eyes of mice that were treated with 0.1% Ce6 (Log10CFU = 7.20 ± 0.16) were no longer different from those seen in mice of the sham treated control group (Log10CFU = 6.65 ± 0.67, P = 0.101). Similarly, the clinical scores observed 72 h post infection in mice treated by PDI with 0.1% Ce6 and red light (clinical score = 3.7 ± 0.5) were not significantly different from those seen in the sham treated control group (clinical score = 4.0 ± 0.0, P = 0.394) (Fig. 6). Moreover, clinical scores increased significantly from hour 12 to day 2 (P = 0.002), and from hour 12 to day 3 (P = 0.002) in both groups, when the development of infection symptoms over time within a treatment group were compared. Representative corneal manifestations of mice are shown in Fig. 7.

Means with standard deviations are shown. 0.1% chlorin e6 (Ce6) was used in PDI at hour 12, while 0% Ce6 was used in control group. There was no significant difference between the two groups. Clinical scores of 0% Ce6 group increased significantly from hour 12 to day 2 (*P = 0.002), and from hour 12 to day 3 (*P = 0.002). Similarly, clinical scores of 0.1% Ce6 group increased significantly from hour 12 to day 2 (*P = 0.002), and from hour 12 to day 3 (*P = 0.002).

Representative corneal manifestations of mice treated by regimen II (chlorin e6 mediated PDI at hour 12 post infection), in which PDI was mediated by (A,B,C) 0%, (D,E,F) 0.1% chlorin e6 (Ce6). Photos were taken (A,D) right before infection of P. aeruginosa (hour 0), (B,E) before PDI (hour 12), and (C,F) on day 3. (B,E) At hour 12, corneal infiltrations were mild (clinical score 1), and the epithelial scratches made for infection of P. aeruginosa were still clearly seen. (C,F) The corneal infiltration was more severe in both mice on day 3 (clinical score 4).

Regimen III (methylene blue mediated PDI at 24 h post infection)

The photosensitizer MB is known to kill P. aeruginosa in vitro upon activation by red light at concentrations of about 100 μM (equivalent to 0.003%), while immune cells are largely spared by this treatment49. To test whether the increased outgrowth of PA54 seen in the eyes of mice treated with the 0.1% Ce6 gel at hour 72 post infection (Fig. 2B) might have been caused by an increased impairment of immune cells, we next tested the impact of PDI by MB and red light (λ = 670 nm) at 24 h post infection to eradicate this pathogen in vivo in our infective keratitis model. To this end, only the bacterial loads 48 h post PDI were determined (Fig. 8). PDI by 0.005% MB and red light applied 24 h post infection yielded in CFU values (Log10CFU = 7.25 ± 0.28) that were largely comparable to those seen in the control group (Log10CFU = 6.98 ± 0.15, P = 0.060). Likewise, the clinical scores observed 48 h and 72 h post infection in mice treated by PDI with 0.005% MB and red light (clinical scores = 3.8 ± 0.4 and 3.7 ± 0.5 for 48 and 72 h post infection) were not significantly different from those seen in the sham treated control group (clinical scores = 3.7 ± 0.5 and 4.0 ± 0.0 for 48 and 72 h post infection, P > 0.394) (Fig. 9). However, when the development of infection symptoms over time within a treatment group were compared, clinical scores of the sham treated control group increased significantly from hour 24 to day 3 (P = 0.002), while clinical scores of the 0.005% MB group increased significantly from hour 24 to day 2 (P = 0.041). Representative corneal manifestations of mice are shown in Fig. 10.

Means with standard deviations are shown. 0.005% methylene blue (MB) was used in PDI at hour 24, while 0% MB was used in control group. There was no significant difference between the two groups. Clinical scores of 0% MB group increased significantly from hour 24 to day 3 (*P = 0.002). Clinical scores of 0.005% MB group increased significantly from hour 24 to day 2 (*P = 0.041).

Representative corneal manifestations of mice treated by regimen III (methylene blue mediated PDI at 24 h post infection), in which PDI was mediated by (A,B,C) 0%, (D,E,F) 0.005% methylene blue (MB). Photos were taken (A,D) right before infection of P. aeruginosa (hour 0), (B,E) before PDI (hour 24), and (C,F) on day 3. (B,E) At hour 24, characteristic infiltration rings of P. aeruginosa keratitis were clearly seen (both clinical score 3). (C,F) The corneal infiltration was more severe in both mice on day 3 (clinical score 4).

Discussion

Our current study assessed the effectivity of corneal PDI by the photosensitizer Ce6 and red light (λ = 670 nm) against MDR-PA keratitis in a murine infection model. We observed that a single PDI treatment with this photosensitizer/light combination significantly decreased the bacterial load in infected eyes by more than 90% at one h post PDI when Ce6 concentrations of 0.01% and 0.05% were utilized, indicating that this PDI procedure exhibits a bactericidal effect in the mouse cornea in vivo as it does in vitro41,42,43,44,50.

An interesting finding is that the highest killing efficiency of PDI by Ce6/red light was not achieved by the highest concentration of Ce6, i.e. 0.1%, but rather by lower Ce6 concentrations. Such a nonlinear correlation between concentration and photodynamic inactivation effect has been observed for many photosensitizers49, and is in line with our previous in vitro findings, indicating a dose-dependent bactericidal effect of PDI by Ce6 and red light against clinical P. aeruginosa isolates44. An explanation for this finding might be that an excess of the photosensitizer decreases the transmission of light required for efficient singlet oxygen generation49. Alternatively, higher Ce6 concentrations might induce the expression of export systems in P. aeruginosa resulting in a decreased concentration of the photosensitizer at/in the bacterial cell. However, the molecular mechanisms responsible for decreased susceptibility of P. aeruginosa cells against PDI in presence of increased concentrations of Ce6 still need to be clarified.

The observations of equal to higher CFU values in the eyes of Ce6 treated mice at 72 h post infection (i.e. 48 h post PDI treatment) demonstrated on the other hand that a single PDI treatment was insufficient in resolving the infection in vivo. Especially the significant bacterial overgrowth induced by the 0.1% Ce6 PDI treatment at day 3 of regimen I is a matter of concern, although this bacterial overgrowth was not seen when Ce6 concentrations ≤0.05% were utilized. This finding is supported by previous clinical case reports, indicating an increased risk of microbial infections as a complication that may be induced by corneal crosslinking29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38.

A solution to the possible bacterial overgrowth is crucial for the long-term safety of corneal PDI. A safe corneal PDI can be applied repeatedly on the infected cornea until all bacteria are eradicated, which certainly maximizes the potency. To explore a safer PDI protocol, we carried out the experiments of regimen II and regimen III. Since P. aeruginosa overgrowth, the main problem, was on day 3, we only measured the CFU on day 3 in regimen II and regimen III.

In regimen II, we focused on 0.1% Ce6, as only this photosensitizer concentration induced a significant bacterial overgrowth in regimen I. When animals were treated once by PDI with 0.1% Ce6 at 12 h post infection, the clinical scores on day 3 did no longer differ from those seen in the eyes of the sham treated control group, suggesting that the risk of bacterial overgrowth might be decreased when PDI can be applied early in infection.

An inconsistency between the milder corneal symptom and higher bacterial load was found in the group treated by 0.1% Ce6 mediated PDI on day 3 of regimen I. A possible explanation might be that a higher proportion of inflammatory cells (mainly neutrophils) recruited to the focus of corneal infection were killed by this PDI regimen, leading to a reduced inflammatory response at the later stage of infection, however, at the cost of bacterial overgrowth.

To test this hypothesis, we used the photosensitizer MB in combination with red light for PDI, which was reported to spare neutrophils at concentrations of about 100 μM, and compared its effectivity to kill P. aeruginosa in the murine corneal scratch model with that of Ce6 mediated PDI49. Taking into account the insufficient diffusion of this photosensitizer into the corneal stroma51, the molar concentration of 0.005% MB used in regimen III was 156 μM, and thus slightly higher than the 100 μM MB recommended in a previous in vitro study49, but just equivalent to 0.009% Ce6. Moreover, for the same amount of substance, the ROS generated from irradiated MB is just about 80% of that of Ce637. Clinical scores of the group treated by MB mediated PDI were not different from those of the control group, suggesting that the corneal infiltration was not markedly affected by this PDI treatment. Yet in regimen III, the group treated by MB mediated PDI showed a considerable tendency of bacterial overgrowth on day 3, compared with the control group (P = 0.060), while the group treated by 0.01% Ce6 mediated PDI did not show such a bacterial overgrowth on day 3 (P = 0.333). This finding is supported by the previous study that shows higher efficiency of Ce6 in comparison with MB in PDI of Gram-positive bacteria in vitro52. Since MB is not better than Ce6 in preventing bacterial overgrowth either, further study is required to compare more different photosensitizers.

Considering the potential of PDI as treatment option against infectious keratitis induced by MDR bacteria, additional experiments are warranted to better uncover the mechanism(s) that promote the bacterial regrowth after PDI treatment. The overall susceptibility of a pathogen to PDI may also have a profound effect on the bacterial regrowth after PDI. PDI of Gram-negative bacteria is more challenging than of Gram-positive bacteria, because Gram-negative bacteria are surrounded by a less permeable envelop consisting of an inner cytoplasmic membrane and an outer membrane, while Gram-positive bacteria are surrounded by a single cytoplasmic membrane and a porous cell wall53. The overall outer membrane permeability of P. aeruginosa is even lower than that of most other Gram-negative bacteria, for example, 12 to 100-fold lower than that of Escherichia coli54. Thus, PDI might be particularly suited as therapy option against keratitis caused by MDR Gram-positive bacteria.

After all, Ce6, and additionally MB, are just two of the most basic photosensitizers applied for PDI. A large number of novel photosensitizers have been developed recently. In some in vitro studies, it has been suggested that polycationic conjugates of poly-L-lysine and Ce6 have higher efficiency for Gram-negative bacteria than free Ce642,55. Some photosensitizers even allow selective targeting and killing bacteria in the presence of mammal cells56,57,58. The development of the latter group of photosensitizers can not only improve the antibacterial killing potency, but also very likely to affect the safety of PDI. We are looking forward to further studies that address the in vivo efficiency of these novel substances against bacterial corneal infections.

In comparison with PDI, many other studies looked at different experimental approaches for treating P. aeruginosa keratitis. An animal study has compared the efficacy of antibiotics to treat P. aeruginosa keratitis59, and found that moxifloxacin, levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin were equally effective against the P. aeruginosa isolate tested. However, when keratitis is caused by a fluoroquinolone-resistant P. aeruginosa isolate, which are on the rise in many regions of the world, this class of antibiotics won’t be any longer a valid therapy option. Some other novel tools, such as bacteriophages and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), are now under development, and each tool has its own risks and advantages. A recent study indicated for example the efficacy of bacteriophage KPP12 for the treatment of P. aeruginosa keratitis in vivo60. However, this study demonstrated that the bacteriophage failed to lyse about one third of the clinical P. aeruginosa strains tested, indicating that this therapy is likely to fail in a large number of cases. The AMP esculentin-1a(1–21)NH2, a frog skin-derived peptide, was also recently reported to significantly reduce the severity of infection in a murine P. aeruginosa keratitis model61, a three log10 reduction was achieved when the AMP was applied three times per day for four days post infection. However, the authors noted that the disease was still progressive even under this intensive regimen.

In summary, our current study has proven that Ce6 mediated PDI is able to cause about one log10 reduction of the MDR-PA cell pool in a murine keratitis model. However, the high numbers of bacterial cells seen at later stages post PDI suggest that consecutive rounds of PDI are required to reduce the amount of bacterial cells in infected eyes in a way that the host immune system can control the infection. The differences in bacterial growth observed after PDI with increasing photosensitizer concentration indicate furthermore that care needs to be taken to identify the optimal dose of photosensitizer to effectively decrease the bacterial burden without causing too many side effects that may interfere with bacterial clearance.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Agar plate of TrypticaseTM soy agar with 5% sheep blood (TSBA) (Becton Dickinson GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). DifcoTM LB broth, Lennox (LB-L) (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, USA). Midazolam (Hameln Pharma Plus GmbH, Hameln, Germany). Fentanyl (Hameln Pharma Plus GmbH, Hameln, Germany). DomitorTM medetomidine hydrochloride (Orion Corporation, Espoo, Finnland). Naloxone hydrochloride (Inresa Arzneimtittel GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). Flumazenil (Inresa Arzneimtittel GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). AntisedanTM atipamezole hydrochloride (Orion Corporation, Espoo, Finnland). Sodium chloride (VWR International Ltd., Leuven, Belgium). Chlorin e6 gel (using hydroxypropyl methylcellulose as gel-base) (by courtesy of APOCARE Pharma GmbH, Bielefeld, Germany). Methylene blue solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany).

Bacterial strain and culture conditions

The MDR P. aeruginosa strain PA54, isolated from human infection, was collected in 2009 at the Institute of Medical Microbiology and Hygiene, Saarland University Medical Center, Homburg, Germany. The resistance profile of PA54 was determined using the automated VITEK 2 system (bioMérieux GmbH, Nürtingen, Germany). PA54 was routinely cultivated overnight on TSBA at 37 °C.

Murine corneal scratch model

Mice

In preliminary experiments, we found that in mice younger than 6 months, P. aeruginosa keratitis showed a trend of spontaneous resolution during one week. Therefore, we used eight-to-eleven month old female C57BL/6N mice, which were purchased from Janvier (Le Genest Saint Isle, France) and kept under specific pathogen-free conditions according to the regulations of German veterinary law. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the German legislation on protection of animals and the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, Washington, USA), and were approved by the local State Review Boards (Landesamt für Soziales, Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz) of Saarland following the national guidelines for the ethical and humane treatment of animals.

Inoculum preparation

PA54 was grown overnight in LB-L at 37 °C, diluted in fresh medium in a ratio of 1:100, and incubated at 37 °C and 150 rpm shaking for 3 hours. Bacteria from the exponential growth phase were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in PBS, resuspended in fresh LB-L to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 10. The number of viable cells was determined by plating out serial dilutions on TSBA. CFU were counted after incubation overnight at 37 °C.

Infection

The time of infection of mice was deemed as hour 0 on day 0 of the experiment. Mice were narcotized by intraperitoneal injection of 10 μl/g anesthetic consisting of 5 μg/ml Fentanyl, 0.5 mg/ml midazolam and 0.05 mg/ml medetomidine hydrochloride in 0.9% sodium chloride solution. The natural tear flow was suppressed by dropping 10 μl of a 0.6% acetyl-cysteine solution onto the cornea. Subsequently, mice were placed under a stereo-microscope, and three linear scratches (each ~2 mm) were made on the ocular surface of the left eye of each mouse by a 27 gauge syringe needle to expose the subepithelial stroma. 5 μl of the PA54 suspension, corresponding to 1 × 106 CFU, were pipetted onto the mechanically harmed cornea when mice were lateral recumbent. The bacterial solution was left on the eye for 20 minutes, and mice were subsequently awaked by injecting 10 μl/g antidote consisting of 0.12 mg/ml naloxone hydrochloride, 0.05 mg/ml flumazenil and 0.25 mg/ml atipamezole hydrochloride in 0.9% sodium chloride solution.

Grading of corneal infections

The corneal manifestation of the PA54 induced keratitis in the infected mouse eyes were examined daily under a stereomicroscope, and recorded as a clinical score using the following scale: Score 0, entire cornea clear; score 1, <50% cornea is semi-transparent (iris color behind the lesion can be identified); score 2, >50% cornea is semi-transparent; score 3, <50% cornea is opaque (iris color behind the lesion cannot be identified); score 4, >50% cornea is opaque; score 5, corneal spontaneous perforation or phthisis bulbi. Corneal photos were taken under the stereomicroscope when mice were in anesthesia.

Bacterial load determinations

Enucleated mouse eyes were homogenized with a POLYTRON PT 1200 E Manual Disperser (Kinematica AG, Lucerne, Switzerland) in 1 ml LB-L, and serial dilutions of this homogenate plated on TSBA. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, CFU were counted.

PDI studies

All steps involving Ce6 were carried out in a dark room under weak yellow light exposure (λ = 596 nm) to avoid activation of the photosensitizer. Three regimens of PDI were tested (Fig. 1). In all regimens, corneal epithelia of narcotized mice were removed by a hockey epithelium removal knife prior to PDI. The irradiation setting to activate Ce6 was identical in all regimens, with 6 minutes irradiation of red light (λ = 670 nm), equivalent to an energy dose of 24 J/cm2.

Regimen I

At 24 h post infection, corneal epithelia were removed from infected eyes, and about 50 μl of a 0% (hydroxypropyl methylcellulose gel-base only), 0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% Ce6 gel dabbed onto the infected mouse cornea, respectively. Mice were then left in darkness for 30 minutes to allow the penetration of Ce6 into the corneal tissues. Afterwards, gel residues were carefully removed with cotton swabs, and mouse corneas irradiated as indicated above. Mice were euthanized either 1 h post PDI or 48 h post PDI, the infected eyes enucleated and subsequently homogenized for CFU determinations.

Regimen II

Corneal epithelia were removed from infected eyes at 12 h post infection, and about 50 μl of a 0% and 0.1% Ce6 gel dabbed onto the infected mouse cornea, respectively. The PDI treatment was carried out as described before. Mice were euthanized 60 h post PDI and handled as described above.

Regimen III

Corneal epithelia were removed from infected eyes at 24 h post infection, and about 20 μl of a 0.005% MB solution and PBS dropped onto the infected mouse cornea, respectively. The PDI treatment was carried out as described before. Mice were euthanized 48 h post PDI, and handled as described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0. Since bacterial growth data is a typical variable that follows the log-normal distribution62, after log transformation of the CFU values, independent samples t test following analysis of variance was used to compare Log10CFU. Mann-Whitney U test following Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare clinical scores. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wu, M.-F. et al. Chlorin e6 mediated photodynamic inactivation for multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis in mice in vivo. Sci. Rep. 7, 44537; doi: 10.1038/srep44537 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Shah, A., Sachdev, A., Coggon, D. & Hossain, P. Geographic variations in microbial keratitis: an analysis of the peer-reviewed literature. Br J Ophthalmol 95, 762–767, doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.169607 (2011).

Hazlett, L. D. Corneal response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Prog Retin Eye Res 23, 1–30, doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2003.10.002 (2004).

Levy, S. B. & Marshall, B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat Med 10, S122–129, doi: 10.1038/nm1145 (2004).

Lister, P. D., Wolter, D. J. & Hanson, N. D. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev 22, 582–610, doi: 10.1128/CMR.00040-09 (2009).

McDonald, E. M., Ram, F. S., Patel, D. V. & McGhee, C. N. Topical antibiotics for the management of bacterial keratitis: an evidence-based review of high quality randomised controlled trials. Br J Ophthalmol 98, 1470–1477, doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304660 (2014).

Willcox, M. D. Review of resistance of ocular isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and staphylococci from keratitis to ciprofloxacin, gentamicin and cephalosporins. Clinical & experimental optometry 94, 161–168, doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2010.00536.x (2011).

Vazirani, J., Wurity, S. & Ali, M. H. Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Keratitis: Risk Factors, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcomes. Ophthalmology 122, 2110–2114, doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.007 (2015).

Jain, R., Murthy, S. I. & Motukupally, S. R. Clinical outcomes of corneal graft infections caused by multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cornea 33, 22–26, doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000011 (2014).

Wong, R. L., Gangwani, R. A., Yu, L. W. & Lai, J. S. New treatments for bacterial keratitis. Journal of ophthalmology 2012, 831502, doi: 10.1155/2012/831502 (2012).

Szentmary, N., Goebels, S., Bischoff, M. & Seitz, B. [Photodynamic therapy for infectious keratitis]. Der Ophthalmologe: Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft 109, 165–170, doi: 10.1007/s00347-011-2511-x (2012).

Huang, L. et al. Type I and Type II mechanisms of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy: an in vitro study on gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Lasers Surg Med 44, 490–499, doi: 10.1002/lsm.22045 (2012).

Tavares, A. et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy: study of bacterial recovery viability and potential development of resistance after treatment. Mar Drugs 8, 91–105, doi: 10.3390/md8010091 (2010).

Winckler, K. D. Special section: focus on anti-microbial photodynamic therapy (PDT). J Photochem Photobiol B 86, 43–44, doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2006.09.005 (2007).

Pavan-Langston, D. & Langston, R. H. Recent advances in antiviral therapy. Int Ophthalmol Clin 15, 89–100 (1975).

O’Day, D. M. et al. Proflavine photodynamic viral inactivation in herpes simplex keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol 79, 941–948 (1975).

Perlin, M., Mao, J. C., Otis, E. R., Shipkowitz, N. L. & Duff, R. G. Photodynamic inactivation of influenza and herpes viruses by hematoporphyrin. Antiviral Res 7, 43–51 (1987).

Chen, Z., Xuguang, S., Zhiqun, W. & Ran, L. In vitro amoebacidal activity of photodynamic therapy on Acanthamoeba. Br J Ophthalmol 92, 1283–1286, doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.134288 (2008).

Mito, T. et al. Effect of photodynamic therapy with methylene blue on Acanthamoeba in vitro . Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53, 6305–6313, doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9828 (2012).

Kashiwabuchi, R. T. et al. Assessment of fungal viability after long-wave ultraviolet light irradiation combined with riboflavin administration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 251, 521–527, doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2209-z (2013).

Arboleda, A. et al. Assessment of rose bengal versus riboflavin photodynamic therapy for inhibition of fungal keratitis isolates. Am J Ophthalmol 158, 64–70 e62, doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.04.007 (2014).

Kashiwabuchi, R. T. et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of photodynamic therapy (UVA/riboflavin) against Staphylococcus aureus. Arq Bras Oftalmol 75, 423–426 (2012).

Halili, F. et al. Rose bengal and riboflavin mediated photodynamic therapy to inhibit methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus keratitis isolates. Am J Ophthalmol, doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.03.014 (2016).

Kharkwal, G. B., Sharma, S. K., Huang, Y. Y., Dai, T. & Hamblin, M. R. Photodynamic therapy for infections: clinical applications. Lasers Surg Med 43, 755–767, doi: 10.1002/lsm.21080 (2011).

Raiskup, F. & Spoerl, E. Corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet A. I. Principles. Ocul Surf 11, 65–74, doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2013.01.002 (2013).

Makdoumi, K., Mortensen, J. & Crafoord, S. Infectious keratitis treated with corneal crosslinking. Cornea 29, 1353–1358, doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181d2de91 (2010).

Makdoumi, K., Mortensen, J., Sorkhabi, O., Malmvall, B. E. & Crafoord, S. UVA-riboflavin photochemical therapy of bacterial keratitis: a pilot study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 250, 95–102, doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1754-1 (2012).

Shetty, R., Nagaraja, H., Jayadev, C., Shivanna, Y. & Kugar, T. Collagen crosslinking in the management of advanced non-resolving microbial keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 98, 1033–1035, doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-304944 (2014).

Chan, E., Snibson, G. R. & Sullivan, L. Treatment of infectious keratitis with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A irradiation. J Cataract Refract Surg 40, 1919–1925, doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.09.001 (2014).

Kymionis, G. D. et al. Herpetic keratitis with iritis after corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet A for keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 33, 1982–1984, doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.06.036 (2007).

Pollhammer, M. & Cursiefen, C. Bacterial keratitis early after corneal crosslinking with riboflavin and ultraviolet-A. J Cataract Refract Surg 35, 588–589, doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.09.029 (2009).

Rama, P., Di Matteo, F., Matuska, S., Paganoni, G. & Spinelli, A. Acanthamoeba keratitis with perforation after corneal crosslinking and bandage contact lens use. J Cataract Refr Surg 35, 788–791, doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.09.035 (2009).

Perez-Santonja, J. J., Artola, A., Javaloy, J., Alio, J. L. & Abad, J. L. Microbial keratitis after corneal collagen crosslinking. J Cataract Refr Surg 35, 1138–1140, doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.01.036 (2009).

Sharma, N., Maharana, P., Singh, G. & Titiyal, J. S. Pseudomonas keratitis after collagen crosslinking for keratoconus: Case report and review of literature. J Cataract Refr Surg 36, 517–520, doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.08.041 (2010).

Ferrari, G., Iuliano, L., Vigano, M. & Rama, P. Impending corneal perforation after collagen cross-linking for herpetic keratitis. J Cataract Refr Surg 39, 638–641, doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.02.006 (2013).

Gautam, Jhanji, V., Satpathy, G., Khokhar, S. & Agarwal, T. Microsporidial keratitis after collagen cross-linking. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 21, 495–497, doi: 10.3109/09273948.2013.824105 (2013).

Rana, M., Lau, A., Aralikatti, A. & Shah, S. Severe microbial keratitis and associated perforation after corneal crosslinking for keratoconus. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 38, 134–137, doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2014.10.004 (2015).

Cagil, N., Sarac, O., Cakmak, H. B., Can, G. & Can, E. Mechanical epithelial removal followed by corneal collagen crosslinking in progressive keratoconus: short-term complications. J Cataract Refract Surg 41, 1730–1737, doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.12.058 (2015).

Kodavoor, S. K., Sarwate, N. J. & Ramamurhy, D. Microbial keratitis following accelerated corneal collagen cross-linking. Oman J Ophthalmol 8, 111–113, doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.159259 (2015).

Shih, M. H. & Huang, F. C. Effects of photodynamic therapy on rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52, 223–229, doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5593 (2011).

El-Laithy, H. M., Nesseem, D. I., El-Adly, A. A. & Shoukry, M. Moxifloxacin-Gelrite in situ ophthalmic gelling system against photodynamic therapy for treatment of bacterial corneal inflammation. Arch Pharm Res 34, 1663–1678, doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-1011-5 (2011).

Park, J. H. et al. Antimicrobial effect of photodynamic therapy using a highly pure chlorin e6. Laser Med Sci 25, 705–710, doi: 10.1007/s10103-010-0781-1 (2010).

Tegos, G. P. et al. Protease-stable polycationic photosensitizer conjugates between polyethyleneimine and chlorin(e6) for broad-spectrum antimicrobial photoinactivation. Antimicrob Agents Ch 50, 1402–1410, doi: 10.1128/Aac.50.4.1402-1410.2006 (2006).

Schastak, S., Gitter, B., Handzel, R., Hermann, R. & Wiedemann, P. Improved photoinactivation of gram-negative and gram-positive methicillin-resistant bacterial strains using a new near-infrared absorbing meso-tetrahydroporphyrin: a comparative study with a chlorine e6 photosensitizer photolon. Methods and findings in experimental and clinical pharmacology 30, 129–133, doi: 10.1358/mf.2008.30.2.1165448 (2008).

Winkler, K. et al. In Vitro Effectiveness Of Photodynamic Therapy Against Multi-resistant Pathogens. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 53, 6206–6206 (2012).

Ochsner, M. Photophysical and photobiological processes in the photodynamic therapy of tumours. J Photochem Photobiol B 39, 1–18 (1997).

Bergendi, L., Benes, L., Durackova, Z. & Ferencik, M. Chemistry, physiology and pathology of free radicals. Life Sci 65, 1865–1874 (1999).

Griffiths, H. R., Mistry, P., Herbert, K. E. & Lunec, J. Molecular and cellular effects of ultraviolet light-induced genotoxicity. Crit Rev Cl Lab Sci 35, 189–237, doi: 10.1080/10408369891234192 (1998).

Winkler, K. et al. Photodynamic inactivation of multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by chlorin e6 and red light (lambda = 670nm). J Photochem Photobiol B 162, 340–347, doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.07.007 (2016).

Tanaka, M. et al. Optimal Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy of Infections Should Kill Bacteria but Spare Neutrophils. Photochem Photobiol 88, 227–232, doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.01005.x (2012).

Simon, C., Wolf G, Walther M, et al. Photodynamic inactivation of pathogens causing infectious keratitis. SPIE; 8931:89310T (2014).

Seiler, T. G. et al. Two-Photon Fluorescence Microscopy for Determination of the Riboflavin Concentration in the Anterior Corneal Stroma When Using the Dresden Protocol. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 56, 6740–6746, doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17656 (2015).

Gad, F., Zahra, T., Hasan, T. & Hamblin, M. R. Effects of growth phase and extracellular slime on photodynamic inactivation of gram-positive pathogenic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48, 2173–2178, doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2173-2178.2004 (2004).

Dai, T., Huang, Y. Y. & Hamblin, M. R. Photodynamic therapy for localized infections–state of the art. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 6, 170–188, doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.10.008 (2009).

Hancock, R. E. Resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis 27 Suppl 1, S93–99 (1998).

Hamblin, M. R. et al. Polycationic photosensitizer conjugates: effects of chain length and Gram classification on the photodynamic inactivation of bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 49, 941–951 (2002).

Long, Y. et al. Novel polymeric nanoparticles targeting the lipopolysaccharides of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Pharm 502, 232–241, doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.02.021 (2016).

Rice, D. R., Gan, H. Y. & Smith, B. D. Bacterial imaging and photodynamic inactivation using zinc(II)-dipicolylamine BODIPY conjugates. Photoch Photobio Sci 14, 1271–1281, doi: 10.1039/c5pp00100e (2015).

Li, K. et al. Selective Photodynamic Inactivation of Bacterial Cells over Mammalian Cells by New Triarylmethanes. Langmuir 30, 14573–14580, doi: 10.1021/la5028724 (2014).

Thibodeaux, B. A. et al. Quantitative comparison of fluoroquinolone therapies of experimental gram-negative bacterial keratitis. Curr Eye Res 28, 337–342 (2004).

Fukuda, K. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis in mice: effects of topical bacteriophage KPP12 administration. PLoS One 7, e47742, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047742 (2012).

Kolar, S. S. et al. Esculentin-1a(1-21)NH2: a frog skin-derived peptide for microbial keratitis. Cell Mol Life Sci 72, 617–627, doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1694-0 (2015).

Limpert, E., Stahel, W. A. & Abbt, M. Log-normal distributions across the sciences: Keys and clues. Bioscience 51, 341–352, doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0341:Lndats]2.0.Co;2 (2001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B. and T.T. designed the experiments. M.B., T.T., D.H. and H.J.F. provided experimental devices and materials. M.F.W. and M.D. performed the experiments. M.L. analyzed the data. M.F.W. wrote the main manuscript text. M.F.W. and N.S. prepared figures. M.B. and B.S. proofread the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, MF., Deichelbohrer, M., Tschernig, T. et al. Chlorin e6 mediated photodynamic inactivation for multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis in mice in vivo. Sci Rep 7, 44537 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44537

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44537

This article is cited by

-

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles boost aggressive cancer response to hydrophilic chlorin e6-mediated photodynamic therapy

Cancer Nanotechnology (2023)

-

Antimicrobial nanomedicine for ocular bacterial and fungal infection

Drug Delivery and Translational Research (2021)

-

Photodynamic antimicrobial activity of new porphyrin derivatives against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Journal of Microbiology (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.