Abstract

Control of pathogens arising from humans, livestock and wild animals can be enhanced by genome-based investigation. Phylogenetically classifying and optimal construction of these genomes using short sequence reads are key to this process. We examined the mammal-infecting unicellular parasite Leishmania adleri belonging to the lizard-infecting Sauroleishmania subgenus. L. adleri has been associated with cutaneous disease in humans, but can be asymptomatic in wild animals. We sequenced, assembled and investigated the L. adleri genome isolated from an asymptomatic Ethiopian rodent (MARV/ET/75/HO174) and verified it as L. adleri by comparison with other Sauroleishmania species. Chromosome-level scaffolding was achieved by combining reference-guided with de novo assembly followed by extensive improvement steps to produce a final draft genome with contiguity comparable with other references. L. tarentolae and L. major genome annotation was transferred and these gene models were manually verified and improved. This first high-quality draft Leishmania adleri reference genome is also the first Sauroleishmania genome from a non-reptilian host. Comparison of the L. adleri HO174 genome with those of L. tarentolae Parrot-TarII and lizard-infecting L. adleri RLAT/KE/1957/SKINK-7 showed extensive gene amplifications, pervasive aneuploidy, and fission of chromosomes 30 and 36. There was little genetic differentiation between L. adleri extracted from mammals and reptiles, highlighting challenges for leishmaniasis surveillance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leishmania are the protozoan parasites responsible for causing the neglected tropical disease leishmaniasis that affects 1.2–2.0 million people annually (WHO 2016), and they also infect livestock, pets and wild animals1. These trypanosomatids typically have a digenetic life cycle existing as flagellated promastigotes in the sandfly vector and as intracellular amastigotes in vertebrate hosts or, possibly, as promastigotes in reptiles2. Over 20 Leishmania species cause leishmaniasis, which presents diverse clinical pathologies: principally visceral leishmaniasis (VL), cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis1,3. VL causes ~50,000 deaths and infects 0.2–0.5 million annually. Localised, diffuse and disseminated CL affects 0.7–1.2 million/year, though this is probably underestimated4. Most infected hosts are asymptomatic carriers that can transmit the parasite to sandflies, and must be targeted to eliminate leishmaniasis.

The genus Leishmania contains 53 known species, initially classified according to the sandfly gut region inhabited by the parasites5 where those developing in the fore-and mid-gut are one subgenus (Leishmania). Parasites developing in the hind-gut form four groups: three are subgenera Paraleishmania, Sauroleishmania and Viannia, and the fourth set is the L. enriettii species complex. The origin of these groups may be at the breakup of the Gondwana supercontinent6, and the most basal one (Paraleishmania) is only in South America. Most genus Leishmania parasites infect insect vectors and mammal hosts, but Sauroleishmania are an exception because their vertebrate hosts are primarily lizards. This host range is particularly striking because Sauroleishmania are closely related to the Leishmania subgenus7, with whom they share a common ancestor ~42 million years ago (95% CI 24–65 mya). Extant Sauroleishmania began diversifying ~16 mya6 into 19 named and two unnamed species found in Asia and Africa8.

Sauroleishmania are globally distributed and a wide range of sandflies and animals act as vectors and hosts, respectively9. L. adleri is associated with lizard- and mammal-feeding vector Phlebotomus clydei in Kenya10 and Sergentomyia (Sergentomyia) dentata in Iran11. Diverse Sauroleishmania infections were described for different lacertid, agamid and gecko desert lizard species, including L. gymnodactyli in North-western China12. Sauroleishmania were isolated from vectors11 and lizards13 in Iran, and L. tarentolae were found in reptile-biting S. (S.) minuta sandflies in Spain14.

The phylogenetic position of Sauroleishmania between the mammal-infecting subgenera Leishmania and Viannia15,16,17 suggests that it represents a widespread lineage of Leishmania that switched from mammals to reptiles as their main hosts. Sauroleishmania member L. tarentolae is a non-pathogenic lab model because it rapidly replicates in lizards. Another Sauroleishmania species, L. adleri undergoes development in the sandfly anterior mid-gut, but can cause transient CL in humans18, and cryptic infections as long as five weeks in hamsters and mice19. Similarly, L. tarentolae can invade human macrophages and may exist as amastigotes in mammals, though with slower replication20,21. L. adleri was the most likely cause of two CL cases in humans22, and human and canine Sauroleishmania VL infections from 1984–90 were found in China23. Amastigotes causing VL rather than CL may have been present in bone marrow and intestinal tissue samples from a 300-year-old mummy from Brazil based on a kinetoplastid DNA (kDNA) amplicon matching L. tarentolae Parrot-TarII but not other Leishmania24.

Leishmaniasis is the most common neglected tropical disease in East Africa, where tropical and sub-tropical climates sustain sandfly populations25. Areas with endemic leishmaniasis show that one in eight people have undergone VL treatment in the Eastern Gedaref state of Sudan26, and parts of Ethiopia in 2014 had a VL rate of 6.7 and a CL one of 0.8 per 1,00027. CL in this region is transmitted by P. papatasi or dubosqui sandflies28 and is frequently associated with L. major28. VL is transmitted by P. orientalis and is typically caused by L. donovani complex species29, though other Leishmania are implicated8.

Strain MARV/ET/1975/HO174 was originally isolated in the rural Setit Humera district of north-western Ethiopia, where Acacia and Balanites forests associated with P. orientalis are used as shelter for overnight sleeping29. The HO174 genome presented here was previously classified as an unusual Leishmania lineage based on multi-locus microsatellite typing (MLMT)30. HO174 was a parasite isolate from an asymptomatic Nile or African grass rat (Arvicanthis niloticus22, which is a reservoir for several Leishmania species and promotes the transmission of L. donovani31 and L. major32 in East Africa.

Genome assemblies have been published for many Leishmania species and isolates since the first Leishmania reference genome sequence of L. major MHOM/IL/1981/Friedlin33. These include L. braziliensis MHOM/BR/1975/M2904, L. infantum MCAN/ES/1998/LLM-87 (JPCM5)34, L. donovani MHOM/NP/2003/BPK282/0cl435, L. mexicana MHOM/GT/2001/U1103cl2536, L. amazonensis MHOM/BR/1973/M226937, and L. panamensis MHOM/PA/94/PSC-138. The L. major genome is 32.8 Mb and contains 8,311 protein-coding genes33, and gene content, genome size and structure are largely conserved across Leishmania. Like other kinetoplastids, Leishmania genomes are comprised of polycistronic transcriptional units (PTUs) separated by strand-switch regions (SSRs) from which RNA polymerase II transcribes in both directions39. PTU expression is regulated by variable RNA stability through mRNA 5′-trans-splicing of the 39-nucleotide mini-exon splice-leader RNA and 3′-polyadenylation prior to translation40. This post-transcriptional regulation means that gene detection, context and copy number can provide insights into function.

The sole sequenced Sauroleishmania genome is for L. tarentolae RTAR/DZ/1939/Parrot-TarII isolated from the lizard Tarentola mauritanica41. It has 36 chromosomes, is aneuploid, and contains 8,530 genes. Its gene-level orthology and PTU arrangement are conserved with L. major41. Here, we generated whole-genome sequence data for MARV/ET/1975/HO174 that we assign as L. adleri (or a closely related species) using a combination of de novo and reference-guided assembly to create an annotated-directed improved draft genome42. We used this data and that of another L. adleri isolate (RLAT/KE/1957/SKINK-7) to characterise the evolution of Sauroleishmania, including genome rearrangements, chromosome structure and gene copy number.

Results

The annotated reference genome of HO174

Preliminary analysis suggested that MARV/ET/1975/HO174 was a member of the Sauroleishmania subgenus, based on mapping 18,183,113 paired-end Illumina HiSeq sequence 75 bp reads to existing reference genomes. Accordingly, we chose to generate a reference genome for this mammal-infecting Sauroleishmania to explore the genetic context of host specificity. The HO174 draft genome assembled using these reads has 69-fold median coverage and spans 30.35 Mb. Compared to the most closely related genome of L. tarentolae Parrot-TarII, it had fewer gaps (Table 1), fewer genes on chromosomes (7,570), more genes on unassigned contigs (389), and shorter chromosome lengths with the exceptions of chromosomes 4, 8, 9, 15, 21, 24 and 28 (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Progressive improvement of the original HO174 assembly

After eliminating low-quality reads and contaminant screening, 17,644,995 read pairs were assembled into 18,480 contigs with an initial N50 of 4.7 Kb Velvet v1.2.0943. Iterative joining of these contigs by SSPACE v2.044 resulted in 5,259 scaffolds with a N50 of 54.2 Kb (Supplementary Table S1). 4,834 (55%) of 8,786 initial gaps were closed45, and nucleotide errors were corrected46 (Supplementary Fig. S2). 627 false scaffold joins identified with REAPR47 increased the number of scaffolds to 5,785 with a N50 of 38.8 Kb and 89.1% error-free bases (EFBs). This EFB rate was similar to the reference genomes for Caenorhabditis elegans WS228 (90.3%), Plasmodium falciparum v3 (94.9%) and Mus musculus GRCm38 (80.1%). The scaffolds were contiguated into (initially) 36 pseudo-chromosomes using the L. tarentolae genome with ABACAS48. 250 contigs >1 Kb long and not assigned to chromosomes spanned 1.66 Mb. Fourteen contigs had homology to minicircle kDNA (290,165 bp), one to maxicircle kDNA (1,075 bp) and one to both minicircle and maxicircle kDNA (1,078 bp).

HO174 represents L. adleri in the Sauroleishmania subgenus

The genus and species of the HO174 genome was assessed using sequences for seven genes (4,677 sites) from 222 isolates from infected patients, mammals and insect vectors for ten Leishmania species49. Orthologous genes were extracted using BLASTn for the HO174 genome, L. tarentolae genome41 and a L. adleri RLAT/KE/1957/SKINK-7 assembly created using Velvet43: SKINK-7 was originally from a long-tailed lizard (Latastia longicaudata), injected into hamsters, and isolated from a rodent spleen. The orthologs were aligned with the 22250 to construct a network51. HO174 was most closely related to SKINK-7 with just two substitutions, compared with 177 between HO174 and L. tarentolae, and 177 between SKINK-7 and L. tarentolae (Fig. 1a).

L. adleri HO174 was a Sauroleishmania isolate based on neighbornet network of the uncorrected p-distances of an alignment of: (a) seven concatenated genes with 4,677 sites for 225 strains. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The L. adleri RLAT/KE/1957/SKINK-7 and MARV/ET/1975/HO174 nodes partially obscure each other. Compared to HO174, there are only two substitutions with SKINK-7, 177 substitutions with L. tarentolae RTAR/DZ/1939/Parrot-TarII, 635 with L. major MRHO/SU/1959/P-STRAIN, 627 with L. infantum MHOM/IT/1985/ISS175, 630 with L. donovani MHOM/YE/1993/LEM2677, and 599 substitutions with L. tropica MHOM/JO/1996/JH-88; (b) two concatenated genes (encoding DNA polymerase α catalytic polypeptide and RNA polymerase II largest subunit) with 2,192 sites of six samples. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The SKINK-7 and HO174 nodes partially obscure each other. Compared to HO174, there are two substitutions with SKINK-7, 21 with L. adleri RLIZ/KE/1954/1433, 49 with L. tarentolae RTAR/DZ/1939/TarVI (from a Tarentola wall gecko) and L. tarentolae Parrot-TarII, 51 with L. hoogstraali RHEM/SD/1963/NG-26 (LV31), 55 with L. gymnodactyli RGYM/SU/1964/Ag (LV247) and 203 with L. major MHOM/SU/1973/5-ASKH. L. adleri SKINK-7 had the same number of substitutions as HO174 with each of these isolates.

We propose that HO174 is a mammalian isolate of L. adleri on the basis of its phylogenetic placement within Sauroleishmania. Two genes previously sequenced, DNA polymerase α catalytic polypeptide (LaHO174_161460) and RNA polymerase II largest subunit (LaHO174_310170)7, were aligned for HO174, L. adleri SKINK-7, L. tarentolae Parrot-TarII, L. tarentolae RTAR/DZ/1939/LV414, L. adleri RLIZ/KE/1954/1433 (LV30) isolated from a Latastia lizard, L. hoogstraali RHEM/SD/1963/NG-26 (LV31) from a Mediterranean house gecko (Hemidactylus turcicus), and L. gymnodactyli RGYM/SU/1964/Ag (LV247) from agamid lizard promastigotes (Agama sanguinolenta, aka Trapelus sanguinolentus) in Turkmenistan that was not pathogenic in mammals52. HO174 was most closely related to L. adleri SKINK-7 with two substitutions and L. adleri 1433 with 21 substitutions (Fig. 1b), whereas the others were more divergent (49 for both L. tarentolae, 51 for L. hoogstraali NG-26, 55 for L. gymnodactyli Ag, Supplementary Table S2). Genome-wide SNP rates confirmed the older common ancestry of HO174 with L. tarentolae (999,834 SNPs, 35.8 SNPs/Kb) and SKINK-7 (855,686 SNPs, 30.6 SNPs/Kb) (Fig. 2a) compared to that of HO174 with SKINK-7 (36,254 or 1.3 SNPs/Kb - SKINK7 had 15,816 heterozygous SNPs). Similarly, SKINK-7 showed less divergence to L. tarentolae than HO174 (Fig. 2b).

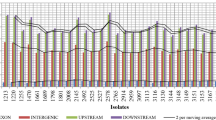

Two ancestral L. adleri chromosome fission events produce 38 chromosomes

We postulate fission of chromosome 36 for HO174 based on a sharp change in coverage after base 989,698 (chromosome 36.1) with 62-fold median coverage that was 5′ of a gap of unknown length (arbitrarily 100 bp). There was 94-fold median coverage 3′ of this gap from base 989,797 to the chromosome end at 2,589,750 - the remainder of chromosome 36 (36.2) (Fig. 3a). This difference between a disomic chromosome 36.1 and a trisomic chromosome 36.2 was suppported by the median coverage (Fig. 4) and read depth allele frequencies (RDAFs) of heterozygous SNPs (Fig. 5). A large change in coverage was evident when the HO174 reads were mapped to the L. adleri (Supplementary Fig. S3) or L. tarentolae reference genomes (Supplementary Fig. S4). No changes in coverage were present for SKINK-7 reads mapped the L. adleri (Supplementary Fig. S5) or L. tarentolae reference genomes (Supplementary Fig. S6), nor for L. tarentolae reads mapped to the L. tarentolae genome (Supplementary Fig. S7). No HO174 read pairs spanned this location when mapped to the L. adleri or the L. tarentolae reference genomes (Supplementary Fig. S8), and the same result was found for SKINK-7 (Supplementary Fig. S9). The fission position split two PTUs at a region homologous to LmjF.36.2560-LmjF.36.2570, showed no major change in GC content, and had no excess read coverage symptomatic of a tandem duplication or collapsed repeat (Supplementary Fig. S8, S9). The long length of chromosome 36.2 (1.6 Mb) suggested it was not an amplification such as an episome or a linear mini-chromosome, which would have a higher copy number and would be <740 Kb53,54. Consequently, this suggests separate chromosomes 36.1 and 36.2 in both L. adleri HO174 and SKINK-7.

Evidence of chromosome fission of (a) L. adleri HO174 chromosome 36 into 36.1 and 36.2; and (b) L. adleri SKINK-7 chromosome 30 into 30.1 and 30.2. Median read coverage (blue) and GC content (pink) were measured in 10 Kb blocks. Black horizontal lines indicate median coverage of that chromosome. The dashed line indicates the fission breakpoints on the original chromosomes: at 989,697 for chromosome 36 and 230,911 for chromosome 30. Genes transcribed from left to right (green) and from right to left (red) are homologous to L. major polycistronic transcriptional units from Thomas et al.67 with their transcription SSRs shown as arrows and origins of replication shown as black crosses.

Read depth allele frequency (RDAF) distributions of normalised SNP counts for: (a) L. adleri HO174 disomic chromosome 36.1 and trisomic chromosome 36.2; (b) L. adleri SKINK-7 tetrasomic chromosome 30.1 and disomic chromosome 30.2; (c) chromosome 12 trisomic in HO174 and disomic in SKINK-7; (d) chromosome 16 disomic in HO174 and trisomic in SKINK-7; (e) tetrasomic chromosome 31 in HO174 and SKINK-7.

We propose a second putative fission of chromosome 30 for SKINK-7 based on a marked shift in coverage when the SKINK-7 reads were mapped to L. adleri HO174 (Fig. 3b) and L. tarenolae (Supplementary Fig. S6). The tetrasomic SKINK-7 chromosome 30.1 spanned L. adleri HO174 bases 1–230,911 with 88-fold median coverage, and the disomic chromosome 30.2 at bases 231,011–1,197,246 (the end) had 43-fold median coverage (Supplementary Fig. S5). The change in somy was verified using read coverage (Fig. 4), the RDAFs of heterozygous SNPs (Fig. 5), and was apparent when mapping to the HO174 and L. tarentolae reference genomes (Supplementary Fig. S8) because the L. tarentolae chromosome also had a gap at the corresponding region (Supplementary Fig. S10). No HO174 or SKINK-7 read pairs spanned the break when mapped to the HO174 reference, and a single SKINK-7 pair crossing the breakpoint when mapped to L. tarentolae had a 57 Kb insert size indicating that one read was incorrectly mapped (Supplementary Fig. S9). The chromosome 30 break had no read pile-up and occurred at a contig gap separating PTUs at a region homologous to LmjF.30.0710 (a cell division cycle 16 gene associated with mitosis) and hypothetical gene LmjF.30.0720. These analyses were consistent with a second fission creating chromosomes 30.1 and 30.2 in L. adleri SKINK-7 and HO174.

L. adleri is largely disomic but aneuploid

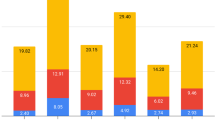

Aneuploidy is an intrinsic feature of Leishmania and was measured using read coverage. Disomy was confirmed from a RDAF distribution peak of ~50% using all chromosomal heterozygous SNPs (Supplementary Fig. S11). L. adleri HO174 was predominantly disomic (including chromosome 36.1) but ten chromosomes were trisomic (6, 8, 12, 13, 14, 20, 23, 25, 29, 36.2; Fig. 4). Chromosome 2 had a somy of 3.4, symptomatic of a mosaic cell population, and chromosome 31 was tetrasomic, as expected given it was nearly always tetrasomic in sequenced Leishmania34,35,36,37,38,41. These estimates were confirmed by the heterozygous SNP RDAF distributions for each chromosome (Supplementary Fig. S12), and were unaffected by GC content bias or local repeats or amplifications (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Repeating this for L. adleri SKINK-7 mapped to the HO174 genome suggested less aneuploidy. Only SKINK-7 chromosome 16 was clearly trisomic, chromosome 10 was marginally so, and chromosome 7 was between di- and tri-somy. Chromosomes 30.1 and 31 were tetrasomic (Fig. 4). The heterozygous SNP RDAF distributions for each chromosome confirmed these estimates, except for chromosome 3 whose distribution suggested trisomy, conflicting with the disomy (2.2 copies) indicated by coverage (Supplementary Fig. S13).

Conserved extra chromosomes would have allowed more heterozygous to accrue over time, however there was no difference in the heterozygous SNP rate per 10 Kb segment for SKINK-7 chromosome 30.1 versus 30.2. This was also true for HO174 chromosome 36.1 versus 36.2, suggesting the differences in somy were recent rather than long-term.

Annotation of the L. adleri HO174 reference genome

A total of 7,959 genes were annotated on the L. adleri HO174 reference, of which 7,849 were protein-coding (Table 1). 7,570 genes were assigned to chromosomes and 389 to unassigned contigs. 7,845 (98.6%) of the total 7,959 genes were annotated by Companion55. Repeating this for the L. tarentolae chromosomes and all unassigned contigs (1,351 sequences) produced 7,893 genes, 92.5% of those on L. tarentolae TriTryDB v6. A further screen for candidate genes in L. adleri HO174 found 117 more, of which 110 had orthologs in L. major, one in L. mexicana, two in L. infantum: four genes without Leishmania orthologs encoded hypothetical gene products with homology to other trypanosomatids (Supplementary Table S3).

Functional and comparative analysis of putative protein-coding orthologous genes

The functional differences and composition of protein-coding genes in L. adleri were categorised into OGs using OrthoMCL56: 7,728 genes (98%) into 7,168 OGs for L. adleri; 8,113 (96%) into 7,368 OGs for L. tarentolae; and 8,367 into 7,519 OGs for L. major (Supplementary Table S4). 98% of L. adleri genes had orthologs in L. major and L. tarentolae, indicating high gene content conservation (Fig. 6). Previously, 250 genes were described as absent in L. tarentolae Parrot-TarII but present in L. major (Raymond et al. 2012). Analysis using OrthoMCLdb v5 and the L. tarentolae TriTrypDB v6 proteome found 280 protein-coding genes in 203 OGs absent in L. tarentolae Parrot-TarII but present in L. major (Supplementary Table S4): 32 had orthologs in L. adleri HO174 (Supplementary Table S5).

Of the 16 L. adleri genes with no L. tarentolae or L. major orthologs (Supplementary Table S6), four had orthologs in at least one of L. infantum, L. mexicana or L. braziliensis, and three had orthologs in one of the five Trypanosoma (T. vivax, T. brucei, T. brucei gambiense, T. cruzi strain CL Brener and T. congolense) but not in L. major, L. infantum, L. mexicana, L. braziliensis or L. tarentolae. Nine had no orthologs in the five Leishmania and five Trypanosoma listed. Eight of these singletons had domains orthologous to variant-specific surface protein genes in parasites such as Giardia, Entamoeba and Trichomonas vaginalis, in which their protein products undergo antigenic variation to evade host immune responses and facilitate host adaptation57. The closest matches for all eight (35–38% identity) was an unnamed product from Phytomonas sp. isolate HART1 - trypanosomatids from this genus can infect plants via an insect vector58.

Four of the 32 orthologs in L. adleri and L. major absent in L. tarentolae (Supplementary Table S5) encoded a serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1, a folate/biopterin transporter, a protein kinase and DNA polymerase kappa. The nucleoside diphosphate kinase B (LaHO174_323240) gene absent in L. tarentolae had five copies in HO174 compared to one in L. major, three each in L. infantum, L. braziliensis and L. mexicana36, and two in L. panamensis PSC-138. A chromosome 19 gene array encoding autophagy-related protein 8 (ATG8/AUT7/APG8/PAZ2, OG5_137181) involved in endocytic trafficking and recycling59 may be absent or partially assembled in L. tarentolae because it had two genes, a gap and collapsed repeat (Tables S6 and S8).

L. adleri copy number variation (CNV) and gene arrays

Four of the six large (5.7–19.8 Kb) CNVs in L. adleri HO174 were in SKINK-7 (Table 2): one was an amplification of 5.7 Kb including a phosphoglycan beta 1,3 galactosyltransferase 5 gene (SCG5, LaHO174_312750) with five copies in HO174. A 15.9 Kb CNV unique to HO174 on chromosome 27 included three genes with copy numbers of 2.5–3.0: ABCA8 (LaHO174_271110), ABCA9 (LaHO174_271120), and LaHO174_271130 (a cysteine peptidase with a calpain-like domain gene). The sole CNV unique to SKINK-7 was non-coding.

Gene arrays were OGs with haploid copy number of at least two: L. adleri had 295 such arrays (Supplementary Table S8), L. tarentolae 281 (Supplementary Table S9), L. major 289 (Supplementary Table S10), and L. panamensis nearly 400, though 285 had just two gene copies (Llanes et al. 2015). Collapsed arrays can be detected where the coverage copy number wastwo-fold or more the assembled version by: L. tarentolae (119 in Supplementary Table S11) had relatively more than L. adleri (62 in Supplementary Table S12). For context, all but twelve arrays in L. major were fully resolved (Supplementary Table S13).

Discussion

A dual strategy combining de novo with reference-guided assembly of short DNA sequence reads produced a high-quality draft of the L. adleri MARV/ET/1975/HO174 genome isolated originally from a rodent. The HO174 reads were de novo assembled into 5,785 scaffolds and contiguated initially into 36 chromosomes using the lizard-infecting L. tarentolae Parrot-TarII genome. The final 30.4 Mb L. adleri genome has 38 chromosomes with 94.5% of assembled sequence on chromosomes and 69-fold median coverage.

Like all Leishmania genomes, it contains tandem arrays of collapsed repeats and genes mapping to multiple chromosomal locations whose true copy number can be inferred using coverage without definite resolution of chromosomal context. Longer reads with greater insert size length variation would map reads more uniquely, enhance contiguation and gene copy number estimates. Despite the inevitable contig gaps, mis-assemblies, and low-quality regions, comparison with other genomes shows that the L. adleri genome is largely complete and an asset for understanding the evolutionary basis of host specificity60.

The L. adleri genome contains 7,959 genes: 7,849 protein-coding ones on 38 chromosomes and 389 on unassigned contigs. Although the vast majority of genes (98.6%) were computationally mapped from reference genomes with perfect matching55, visual inspection remains necessary to discover and correct complex gene models. Here, 32 genes were absent in L. tarentolae but present in Leishmania belonging to other subgenera.

Alignment of seven L. adleri HO174 genes with those of 224 other Leishmania isolates from infected patients, mammals and insects49 showed that HO174 was a Sauroleishmania isolate most closely related to L. adleri RLAT/KE/1957/SKINK-7 and L. adleri RLIZ/KE/1954/1433 compared to L. tarentolae, L. hoogstraali and L. gymnodactyli (Fig. 1). Consequently, HO174 is the first genome sequenced from the Sauroleishmania subgenus isolated from a mammal. Mapping SKINK-7 reads to the HO174 reference also confirmed it as L. adleri rather than L. tarentolae. Previous MLMT could not classify HO174 clearly30 – our work illustrates how genome-wide investigation improves phylogenetic resolution.

The hypothesis of inherent aneuploidy in Leishmania61 was verified in Sauroleishmania HO174, SKINK-7 and Parrot-TarII. The levels of mapped reads and their allelic variants across chromosomes demonstrated that chromosome 36 was split into two portions in L. adleri HO174: a disomic chromosome 36.1 (990 Kb) and a trisomic chromosome 36.2 (1,600 Kb, Supplementary Fig. S12). L. adleri SKINK-7 had this chromosome 36 fission, but not L. tarentolae as indicated previously with long sequence reads41. L. adleri SKINK-7 chromosome 30 was split into two portions: a disomic chromosome 30.1 (231 Kb) and a trisomic chromosome 30.2 (966 Kb). This was present in HO174 without any somy change.

Most Leishmania species have 36 chromosomes, including all members of the Leishmania subgenus – except for 34 in the L. mexicana complex, in which chromosomes 8 and 29 are a fused chromosome 8, and chromosomes 20 and 36 are a fused chromosome 2936. In contrast, chromosome 30 is largely conserved as a single unit in trypanosomatids60. Chromosomal fission resulting in the truncation of chromosome 4 in L. tarentolae LEM115 (365 Kb, similar to Parrot-TarII chromosome 3) isolated from a gecko2 was observed during routine subculture in which six out of 20 clones produced a 340 Kb chromosome 4 A62. One cloned line had cells with both chromosomes 4 and 4 A in which the chromosome 4 A line outgrew the wild-type after re-cloning, suggesting no fitness loss62. Chromosome 4A may have been due to a contraction of the mini-exon gene array, as described for L. major chromosome 263. Trypanosoma cruzi chromosome 11 had a similar coverage change at a SSR (at 248 Kb) where the segment 5′ of the SSR had a uniformly lower coverage than the 3′ segment. This indicated either loss of the 248 Kb region for one chromosome copy with perhaps partial fixation in the cell population64,65, or fission into a monosomic chromosome 11.1 and disomic chromosome 11.2.

Chromosomal fission may be more common at SSRs to preserve RNA polymerase II promoters because transcription is initiated at all SSRs independently of PTU context66. Elevated acetylation of histone H3 signifies these promoters67: L. major has high acetylation at positions equivalent to the L. adleri chromosome 30 and 36 breaks66. Both fission locations coincided with L. adleri and L. major SSRs: this would yield three SSRs at chromosome 36.1 and two for 36.2 (Fig. 3a). The chromosome 30 break was at a SSR, suggesting 3′ to 5′ transcription of chromosome 30.1 with no SSRs, and two SSRs for 30.2 (Fig. 3b).

Viable new chromosomes must have at least one single origin of DNA replication: and these coincide with SSRs for 30 chromosomes out of 36 in L. major66. A single bidirectional origin is typically retained after chromosomal fusion in Leishmania, such as the single origins on the fused L. mexicana chromosomes 8 and 2966. L. major and L. mexicana had chromosome 30 origins at positions equivalent to the L. adleri chromosome 30 break, indicating that replication may proceed from this origin 3′−5′ for chromosome 30.1 and 5′−3′ for 30.2. The chromosome 36 origin at bases 1,110,127–1,116,528 in L. major was at the 5′ end of the L. adleri chromosome 36.266, indicating that a different origin may be used for chromosome 36.1. Consequently, the two fissions may stem from erroneous chromosome replication68, and may be functionally neutral, though an additional DNA replication origin on a new chromosome could accelerate cell replication66. Alternative to this model, there could be many low-activity origins of replication per chromosome in Sauroleishmania as suggested for Leishmania promastigotes69.

The single early-firing origins on each L. major chromosome could represent centromeric regions because they are replicated in early S-phase in other eukaryotes66,70. The chromosome 30 fission in L. adleri would result in one origin at the 3′ end of chromosome 30.1 and one origin at the 5′ end of chromosome 30.2 based on homology with L. major. If a centromere was present at this locus it would be split into two parts, with one functional part on each fission product (centric fission)71. The broken chromosome 30 and 36 ends could be protected from degradation through the addition of telomeres, structural rearrangements to protect the chromosomes ends, the development of ring chromosomes through fusion of the broken end with the telomere of the intact end, or translocation of the broken chromosomes onto the end of other intact chromosomes71. No evidence of structural rearrangements at the chromosome ends or fission break regions was found here, though telomeric sequences are highly repetitive and were not assembled fully, highlighting a task for future work.

Conclusions

This study produced the first Leishmania adleri high-quality draft genome for the isolate MARV/ET/1975/HO174, which advances the study of the subgenus Sauroleishmania of reptile-infecting parasites. We show that short read data can produce comprehensive genome assemblies and allowed for enhanced specimen typing. The discovery of two L. adleri chromosome fissions highlights that this feature of genetic diversity may be present in other Trypanosomatid species.

Our results confirm that L. adleri HO174 from a well-known mammalian reservoir of Leishmania was closely related to other isolates of L. adleri originally from lizards. Sauroleishmania are not restricted to reptiles, and human-infecting L. tropica and L. donovani isolates infect lizards, and are likely transferred by Sergentomyia from human to lizard12. There are abundant zoonotic reservoirs of Leishmania including rodents, livestock, mongooses72, bats73, hyraxes1 and dogs. Elimination programmes must treat hosts of any type with high parasitaemia first because they are responsible for most sandfly infections74. Given the expansion of Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia sandfly ranges driven by climate change75 and the extensive gene synteny among Leishmania, broader testing is required to track isolates from human, livestock and wild hosts in light of the viability of potential interspecies hybrids76.

Methods

Genomic data sources

MARV/ET/1975/HO174 was isolated from an African grass rat (Arvicanthis niloticus) on 24/01/1975. It was received by London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine from Liverpool University on 09/09/1980 (Liverpool University cryobank accession LV388). The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute core sequencing group prepared standard Illumina libraries sequenced by an Illumina HiSeq 2000 v3 platform to generate 18,183,113 paired-end 75 bp reads with a median insert size of 400 (ERX180410).

The L. tarentolae RTAR/DZ/1939/Parrot-TarII and L. major Friedlin33 genomes, protein sequences and annotation (GFF) files were downloaded from TriTrypDB v6. Single-end Illumina shotgun 36 bp reads for Parrot-TarII41, 12,680,080 paired-end Illumina Genome Analyzer II 76 bp reads for L. major Friedlin (ERX005636)36, and 18,322,426 paired-end Illumina HiSeq 2000 100 bp reads for L. adleri RLAT/KE/1957/SKINK-7 (aka LRC-L123) (SRX764330)6 were analysed.

Sequence read quality control

The MARV/ET/1975/HO174 library read quality was analysed using FastQC (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). PCR primer sequences were removed based on FastQC alignment matches. Potential DNA contaminants were determined where the species of the top hit in alignments with the Non-redundant Nucleotide Database using BLASTn77 were not in the Kinetoplastida class of the NCBI Taxonomy Database. FastQC was repeated on the decontaminated reads so that reads with a extreme GC content could be removed.

Genome assembly and improvement

The processed reads were assembled de novo using Velvet v1.2.0943 with kmer of 53, expected kmer coverage of 16 and coverage threshold of eight. A kmer of 53 maximised the N50 for contigs >100 bp. These contigs were scaffolded with SSPACE v2.044 because it has previously produced output with fewer scaffolds and longer N50s than Abyss or SOAP44. Gaps were closed using Gapfiller for ten iterations45. Erroneous bases were corrected by re-mapping reads to the scaffolds using iCORN for ten iterations46.

Putative mis-assemblies were screened by splitting scaffolds at potential errors with REAPR47, which evaluated the N50, corrected N50 and the percentage of EFBs after mapping the initial reads to the initial assembly (Supplementary Table S1). EFBs had five or more correctly-oriented read pairs, matched the expected insert size, had no mismatches and a small fragment coverage distribution error47. Scaffold structure and read pair mapping were visually examined using IGV v2.378.

The scaffolds were contiguated into 36 chromosomes using the L. tarentolae genome as a reference with ABACAS48. Gaps >100 bp were shortened to 100 bp and unplaced contigs <1 Kb were removed. Unplaced bin contigs were aligned using MegaBLAST against a database of 753 minicircle and 152 maxicircle kDNA sequences obtained from Genbank76. Contigs with E value <0.01, bitscore >100 and identity >40% were annotated as minicircle or maxicircle kDNA. The final 38 HO174 chromosomes were verified visually by alignment with those for L. tarentolae using the Artemis Comparison Tool (ACT)79.

Phylogenomic characterisation

The genus and species of the HO174 genome was assessed using seven genes from 222 published isolates49. Reads for SKINK-7 were assembled into contigs using Velvet43 with kmer of 53 yielding an assembly with 15,507 contigs and N50 of 4.88 Kb. Orthologous genes were extracted from the HO174 genome, L. tarentolae genome41 and SKINK-7 assembly using BLASTn and aligned with the 222 using Clustal Omega v1.150. A neighbour-net network of uncorrected p-distances was constructed using SplitsTree v4.13.151. To pinpoint the phylogenetic position of HO174 within the L. tarentolae complex, the two genes of five Sauroleishmania species7 were aligned with the HO174 orthologs as above - the phylogenetic structure of each gene was similar (Supplementary Fig. S14).

Gene annotation

The HO174 chromosomes and contigs were annotated by transferring gene models from the L. major genome to HO174 using species-level transfer with RATT80 through Companion55. This system used ab initio gene-finding by Augustus trained on L. major, and predicted tRNA, rRNA and ncRNA genes using Infernal81 and Aragorn82. Open reading frames >450 bp identified by Artemis83 were screened for genes missed by Companion. Putative open reading frames with potential start and stop codons were aligned with the NCBI protein database using BLASTp, where those with an E-value <0.1 and identity >30% were considered as valid coding sequences for manual examination using Artemis and ACT78. This manual correction was used where a gene extended over a gap of unknown length to trim it to the edge of the first gap, and similarly genes with multiple stop codons were adjusted to the first stop codon.

Estimating chromosome copy number

To calculate the chromosome copy number based on coverage, reads were mapped using SMALT v5.7 (www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/smalt/) with parameters set to exhaustive mapping and a maximum insert size of 1000. The reference genomes against which reads were mapped were indexed with a kmer of 13 and step of two. Duplicate reads were removed using Samtools rmdup84 and coverage at each base was retrieved using Bedtools ‘genomecov’ v2.17.085. For each chromosome, we calculated the median read coverage. Assuming that most chromosomes were disomic, the median of these chromosomal values produces a reliable estimate of the coverage of disomic chromosomal coverage, and so dividing it by two gives the haploid value. Thus, the copy number of each chromosome was estimated as the chromosome’s median coverage divided by this haploid value. Chromosome copy numbers were visually confirmed using the RDAF distribution of heterozygous SNPs generated with R packages ggplot2 and gridExtra. RDAFs obtained from Samtools pileup v0.1.11 were binned with a step of 0.05 from 0.15 to 0.85: values outside this range are uninformative in the context of distinguishing somy of up to five, and likely represented sequencing artefacts.

Detection of CNVs

CNVs were examined at non-masked regions using the same coverage-based approach used for chromosome copy numbers. The median haploid copy numbers of non-overlapping 10 Kb blocks were estimated for uniquely mapped reads with mapping quality >30 using Samtools view84 and Bedtools ‘makewindows’ v2.17.085. CNVs were denoted as regions with a two-fold or greater change over the chromosomal median coverage, and were verified visually with ggplot2 and IGV78. The copy number of each L. major, L. tarentolae and L. adleri gene was estimated without removing non-uniquely mapped reads, which could bias estimates due to lower coverage at genes with multiple homologs. HO174 reads were mapped to HO174 with chromosome 36 as a single unit and then again with it split into chromosomes 36.1 and 36.2 at the breakpoint to resolve gene copy number more accurately. Similarly, SKINK-7 reads were mapped to L. adleri HO174 with chromosome 30 as a single block and split into chromosomes 30.1 and 30.2.

Single-nucleotide variant discovery

Repetitive sequences, low-quality regions, homopolymers and small tandem repeats discovered using Tantan v0.1386, segments within 300 bases of contig edges, and regions within 100 bases of gaps were masked to exclude false SNPs. Candidate SNPs were screened with Vcftools v0.1.12b87, Samtools mpileup v0.1.18, Bcftools v0.1.17-dev, and the Samtools 0.1.18 samtools.pl varFilter84 where they had: base quality >25; mapping quality >30; coverage >5 and <100; SNP quality >30; a non-reference RDAF >0.1; a forward-reverse read coverage ratio >0.1 and <0.9; 2+ forward reads, and 2+ reverse reads. SNPs were considered heterozygous if the RDAF >0.1, and homozygous if the RDAF >0.85.

Identification of orthologous groups (OGs) and gene arrays

L. adleri and L. tarentolae proteins were assigned to OrthoMCL OGs using the OrthoMCLdb v5 webserver. This excluded 44 L. adleri genes classified as pseudogenes by Companion: subsequent manual correction indicated these were valid protein coding genes. The results were compared with 11,825 OGs retrieved from OrthoMCLdb release 556 for those in at least one of: L. major strain Friedlin, L. infantum, L. braziliensis, L. mexicana, T. vivax, T. brucei, T. brucei gambiense, T. cruzi strain CL Brener and T. congolense. 7,654 of these OGs were present in at least one of: L. braziliensis, L. infantum, L. major or L. mexicana. The copy number of each OG in L. tarentolae, L. major and L. adleri was estimated from the haploid read coverage of each gene in the OG and summing across all the genes in the OG. Gene arrays were defined as segments containing 2+ haploid gene copies with the same OrthoMCL identifier, and so could be located in cis or trans. Large arrays (10+ gene copies) in L. major, L. adleri HO174 and L. tarentolae were examined and those with unassembled copies were identified by finding arrays with a haploid copy number more than twice the assembled gene number.

Availability of materials and data

The data sets for Leishmania adleri MARV/ET/1975/HO174 are:

[1]DNA read data available with accession number ERX180410 at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/ERX180410 and European Nucleotide Archive http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/ERX180410.

[2]The BioProject PRJEB17628 consensus genome sequence FASTA file at https://figshare.com/articles/L_alderi_HO174_genome_FASTA_file/4645450 and annotation EMBL file at https://figshare.com/articles/L_adleri_HO174_genome_annotation_EMBL_file/4645477.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Coughlan, S. et al. The genome of Leishmania adleri from a mammalian host highlights chromosome fission in Sauroleishmania. Sci. Rep. 7, 43747; doi: 10.1038/srep43747 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Alvar, J. et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One. 7, e35671 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671 (2012).

Simpson, L. & Holz, G., Jr. The status of Leishmania tarentolae/Trypanosoma platydactyli. Parasitol Today. 4, 115–118 (1988).

Gradoni,. L. et al. Failure of a multi-subunit recombinant leishmanial vaccine (MML) to protect dogs from Leishmania infantum infection and to prevent disease progression in infected animals. Vaccine. 23, 5245–5251, doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.001 (2005).

Singh,. V. P. et al. Estimation of under-reporting of visceral leishmaniasis cases in Bihar, India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 82, 9–11, doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0235 (2010).

Lainson, R. & Shaw, J. J. Observations on the development of Leishmania (L.) chagasi Cunha and Chagas in the midgut of the sandfly vector Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz and Neiva). Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 63, 134–145 (1988).

Harkins, K. M., Schwartz, R. S., Cartwright, R. A. & Stone, A. C. Phylogenomic reconstruction supports supercontinent origins for Leishmania. Infect Genet Evol 38, 101–109, doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.11.030 (2016).

Croan, D. G., Morrison, D. A. & Ellis, J. T. Evolution of the genus Leishmania revealed by comparison of DNA and RNA polymerase gene sequences. Mol Biochem Parasitol 89, 149–159 (1997).

Akhoundi, M. et al. A Historical Overview of the Classification, Evolution, and Dispersion of Leishmania Parasites and Sandflies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10, e0004349, doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004349 (2016).

Baneth, G., Koutinas, A. F., Solano-Gallego, L., Bourdeau, P. & Ferrer, L. Canine leishmaniosis - new concepts and insights on an expanding zoonosis: part one. Trends Parasitol. 24, 324–330, doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.04.001 (2008).

Heisch, R. B. On leishmania adleri sp. nov. from lacertid lizards (Latastia sp.) in Kenya. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 52, 68–71 (1958).

Maleki Ravasan, N. et al. Natural infection of sand flies Sergentomyia dentata in Ardebil to Lizard Leishmania. Modares Journal of Medical Sciences: Pathobiology. 10, 65–73 (2008).

Zhang, J. R. et al. Molecular detection, identification and phylogenetic inference of Leishmania spp. in some desert lizards from Northwest China by using internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) sequences. Acta Trop. 162, 83–94, doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.06.023 (2016).

Kazemi, B., Tahvildar-Bideroni, G., Feshareki, S. H. & Javadian, E. Isolation a Lizard Leishmania promastigote from its Natural Host in Iran. 4, 620 (2004).

Bravo-Barriga, D. et al. First molecular detection of Leishmania tarentolae-like DNA in Sergentomyia minuta in Spain. Parasitol Res. 115, 1339–1344, doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4887-z (2016).

Noyes, H. A., Arana, B. A., Chance, M. L. & Maingon, R. The Leishmania hertigi (Kinetoplastida; Trypanosomatidae) complex and the lizard Leishmania: their classification and evidence for a neotropical origin of the Leishmania-Endotrypanum clade. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 44, 511–517 (1997).

Marcili, A. et al. Phylogenetic relationships of Leishmania species based on trypanosomatid barcode (SSU rDNA) and gGAPDH genes: Taxonomic revision of Leishmania (L.) infantum chagasi in South America. Infect Genet Evol. 25, 44–51, doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.04.001 (2014).

Kwakye-Nuako, G. et al. First isolation of a new species of Leishmania responsible for human cutaneous leishmaniasis in Ghana and classification in the Leishmania enriettii complex. Int J Parasitol. 45, 679–684, doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.05.001 (2015).

Manson-Bahr, P. E. & Heisch, R. B. Transient infection of man with a Leishmania (L. adleri) of lizards. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 55, 381–382 (1961).

Adler, S. The behaviour of a lizard Leishmania in hamsters and baby mice. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 4, 61–64 (1962).

Breton, M., Tremblay, M. J., Ouellette, M. & Papadopoulou, B. Live nonpathogenic parasitic vector as a candidate vaccine against visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 73, 6372–6382, doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6372-6382.2005 (2005).

Taylor, V. M. et al. Leishmania tarentolae: utility as an in vitro model for screening of antileishmanial agents. Exp Parasitol. 126, 471–475, doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.05.016 (2010).

Haile, T. T. & Lemma, A. Isolation of Leishmania parasites from Arvicanthis in Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 71, 180–181 (1977).

Yang, B. B. et al. Analysis of kinetoplast cytochrome b gene of 16 Leishmania isolates from different foci of China: different species of Leishmania in China and their phylogenetic inference. Parasit Vectors. 6, 32, doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-32 (2013).

Novo, S. P., Leles, D., Bianucci, R. & Araujo, A. Leishmania tarentolae molecular signatures in a 300 hundred-years-old human Brazilian mummy. Parasit Vectors. 8, 72, doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0666-z (2015).

Hotez, P. J., Woc-Colburn, L. & Bottazzi, M. E. Neglected tropical diseases in Central America and Panama: review of their prevalence, populations at risk and impact on regional development. Int J Parasitol. 44, 597–603, doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.04.001 (2014).

Mueller, Y. K. et al. Burden of visceral leishmaniasis in villages of eastern Gedaref State, Sudan: an exhaustive cross-sectional survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 6, e1872, doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001872 (2012).

W. H. O. Weekly epidemiological record. 22, 285–296 (2016).

el-Hassan, A. M. & Zijlstra, E. E. Leishmaniasis in Sudan. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 95 Suppl 1, S1–17 (2001).

Zijlstra, E. E. & el-Hassan, A. M. Leishmaniasis in Sudan. Visceral leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 95 Suppl 1, S27–58 (2001).

Baleela, R. et al. Leishmania donovani populations in Eastern Sudan: temporal structuring and a link between human and canine transmission. Parasit Vectors 7, 496, doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0496-4 (2014).

Hoogstraal, H. et al. Leishmaniasis in the Sudan Republic: epidemiological findings. Bull World Health Organ 28, 263–265 (1963).

WHO. Control of leishmaniasis. (2010).

Ivens, A. C. et al. The genome of the kinetoplastid parasite, Leishmania major. Science. 309, 436–442, doi: 10.1126/science.1112680 (2005).

Peacock, C. S. et al. Comparative genomic analysis of three Leishmania species that cause diverse human disease. Nat Genet 39, 839–847, doi: 10.1038/ng2053 (2007).

Downing, T. et al. Whole genome sequencing of multiple Leishmania donovani clinical isolates provides insights into population structure and mechanisms of drug resistance. Genome Res 21, 2143–2156, doi: 10.1101/gr.123430.111 (2011).

Rogers, M. B. et al. Chromosome and gene copy number variation allow major structural change between species and strains of Leishmania. Genome Res. 21, 2129–2142, doi: 10.1101/gr.122945.111 (2011).

Real, F. et al. The genome sequence of Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis: functional annotation and extended analysis of gene models. DNA Res. 20, 567–581, doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst031 (2013).

Llanes, A., Restrepo, C. M., Del Vecchio, G., Anguizola, F. J. & Lleonart, R. The genome of Leishmania panamensis: insights into genomics of the L. (Viannia) subgenus. Sci Rep. 5, 8550, doi: 10.1038/srep08550 (2015).

Myler, P. J. et al. Genomic organization and gene function in Leishmania. Biochem Soc Trans. 28, 527–531 (2000).

Clayton, C. & Shapira, M. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression in trypanosomes and leishmanias. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 156, 93–101, doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.07.007 (2007).

Raymond, F. et al. Genome sequencing of the lizard parasite Leishmania tarentolae reveals loss of genes associated to the intracellular stage of human pathogenic species. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 1131–1147, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr834 (2012).

Chain, P. S. et al. Genomics. Genome project standards in a new era of sequencing. Science 326, 236–237, doi: 10.1126/science.1180614 (2009).

Zerbino, D. R. & Birney, E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18, 821–829, doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107 (2008).

Boetzer, M., Henkel, C. V., Jansen, H. J., Butler, D. & Pirovano, W. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics. 27, 578–579, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683 (2011).

Boetzer, M. & Pirovano, W. Toward almost closed genomes with GapFiller. Genome Biol. 13, R56, doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r56 (2012).

Otto, T. D., Sanders, M., Berriman, M. & Newbold, C. Iterative Correction of Reference Nucleotides (iCORN) using second generation sequencing technology. Bioinformatics. 26, 1704–1707, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq269 (2010).

Hunt, M. et al. REAPR: a universal tool for genome assembly evaluation. Genome Biol. 14, R47, doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-5-r47 (2013).

Assefa, S., Keane, T. M., Otto, T. D., Newbold, C. & Berriman, M. ABACAS: algorithm-based automatic contiguation of assembled sequences. Bioinformatics. 25, 1968–1969, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp347 (2009).

El Baidouri, F. et al. Genetic structure and evolution of the Leishmania genus in Africa and Eurasia: what does MLSA tell us. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 7, e2255, doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002255 (2013).

Sievers, F. et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 7, 539, doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75 (2011).

Huson, D. H. & Bryant, D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 23, 254–267, doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030 (2006).

Saf’janova, V. M. & Avakjan, A. A. Use of ferritin-labelled antibodies for differentiating Leishmania species and other Trypanosomatidae. Bull World Health Organ. 48, 289–297 (1973).

Sunkin, S. M. et al. Conservation of the LD1 region in Leishmania includes DNA implicated in LD1 amplification. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 113, 315–321 (2001).

Wilson, K., Beverley, S. M. & Ullman, B. Stable amplification of a linear extrachromosomal DNA in mycophenolic acid-resistant Leishmania donovani. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 55, 197–206 (1992).

Steinbiss, S. et al. Companion: a web server for annotation and analysis of parasite genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W29–34, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw292 (2016).

Li, L., Stoeckert, C. J., Jr. & Roos, D. S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189, doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503 (2003).

Ropolo, A. S., Saura, A., Carranza, P. G. & Lujan, H. D. Identification of variant-specific surface proteins in Giardia muris trophozoites. Infect Immun. 73, 5208–5211, doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.5208-5211.2005 (2005).

Jaskowska, E., Butler, C., Preston, G. & Kelly, S. Phytomonas: trypanosomatids adapted to plant environments. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004484, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004484 (2015).

Mittra, B. et al. Iron uptake controls the generation of Leishmania infective forms through regulation of ROS levels. J Exp Med. 210, 401–416, doi: 10.1084/jem.20121368 (2013).

Jackson, A. P. et al. Kinetoplastid Phylogenomics Reveals the Evolutionary Innovations Associated with the Origins of Parasitism. Curr Biol. 26, 161–172, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.055 (2016).

Mannaert, A., Downing, T., Imamura, H. & Dujardin, J. C. Adaptive mechanisms in pathogens: universal aneuploidy in Leishmania. Trends Parasitol. 28, 370–376, doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.06.003 (2012).

Rovai, L., Tripp, C., Stuart, K. & Simpson, L. Recurrent polymorphisms in small chromosomes of Leishmania tarentolae after nutrient stress or subcloning. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 50, 115–125 (1992).

Iovannisci, D. M. & Beverley, S. M. Structural alterations of chromosome 2 in Leishmania major as evidence for diploidy, including spontaneous amplification of the mini-exon array. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 34, 177–188 (1989).

Reis-Cunha, J. L. et al. Chromosomal copy number variation reveals differential levels of genomic plasticity in distinct Trypanosoma cruzi strains. BMC Genomics. 16, 499, doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1680-4 (2015).

Valdivia, H. O. et al. Comparative genomic analysis of Leishmania (Viannia) peruviana and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis. BMC Genomics. 16, 715, doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1928-z (2015).

Marques, C. A., Dickens, N. J., Paape, D., Campbell, S. J. & McCulloch, R. Genome-wide mapping reveals single-origin chromosome replication in Leishmania, a eukaryotic microbe. Genome Biol. 16, 230, doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0788-9 (2015).

Thomas, S., Green, A., Sturm, N. R., Campbell, D. A. & Myler, P. J. Histone acetylations mark origins of polycistronic transcription in Leishmania major. BMC Genomics. 10, 152, doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-152 (2009).

Sterkers, Y., Lachaud, L., Crobu, L., Bastien, P. & Pages, M. FISH analysis reveals aneuploidy and continual generation of chromosomal mosaicism in Leishmania major. Cell Microbiol 13, 274–283, doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01534.x (2011).

Stanojcic, S. et al. Single-molecule analysis of DNA replication reveals novel features in the divergent eukaryotes Leishmania and Trypanosoma brucei versus mammalian cells. Sci Rep. 6, 23142, doi: 10.1038/srep23142 (2016).

Rocha-Granados, M. C. & Klingbeil, M. M. Leishmania DNA Replication Timing: A Stochastic Event? Trends Parasitol. 32, 755–757 (2016).

Perry, J., Slater, H. R. & Choo, K. H. Centric fission–simple and complex mechanisms. Chromosome Res. 12, 627–40 (2004).

Elnaiem, D. A. et al. The Egyptian mongoose, Herpestes ichneumon, is a possible reservoir host of visceral leishmaniasis in eastern Sudan. Parasitology. 122, 531–536 (2001).

Kassahun, A. et al. Natural infection of bats with Leishmania in Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 150, 166–170, doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.07.024 (2015).

Miller, E. et al. Quantifying the contribution of hosts with different parasite concentrations to the transmission of visceral leishmaniasis in Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop. Dis. 8, e3288, doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003288 (2014).

Han, B. A., Schmidt, J. P., Bowden, S. E. & Drake, J. M. Rodent reservoirs of future zoonotic diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 112, 7039–7044, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501598112 (2015).

Romano, A. et al. Cross-species genetic exchange between visceral and cutaneous strains of Leishmania in the sand fly vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111, 16808–16813, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415109111 (2014).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421, doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 (2009).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 29, 24–26, doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754 (2011).

Carver, T. J. et al. ACT: the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics 21, 3422–3423, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti553 (2005).

Otto, T. D., Dillon, G. P., Degrave, W. S. & Berriman, M. RATT: Rapid Annotation Transfer Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e57, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1268 (2011).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics. 29, 2933–2935, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509 (2013).

Laslett, D. & Canback, B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 11–16, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh152 (2004).

Rutherford, K. et al. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 16, 944–945 (2000).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25, 2078–2079, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 26, 841–842, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033 (2010).

Frith, M. C. A new repeat-masking method enables specific detection of homologous sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e23, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1212 (2011).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 27, 2156–2158, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support through the NUI Galway Ph.D. Fellowship scheme (SC), from the Wellcome Trust via its core funding of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (grant 098051) (MS, JAC). The authors thank: Matthew Berriman and members of the DNA pipelines team at WTSI for generating the sequence library; Cathal Seoighe (NUI Galway), Hideo Imamura and Jean-Claude Dujardin (both Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp) for useful discussions; Tapan Bhattacharyya and Michael Miles (both London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) and Isabel Mauricio (Institute of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Lisbon) for providing DNA and background information on the HO174 isolate; Anne Stone and Kelly Harkins (both Arizona State University) for releasing informative sequence read data; and the DJEI/DES/SFI/HEA Irish Centre for High-End Computing (ICHEC) for of computational facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. performed genome assembly, annotation, comparative genomics, phylogenetic analysis, variant detection, helped design the study and wrote the main manuscript text. P.M. performed genome annotation. M.S. completed genome sequencing. G.S. helped design the study and wrote the main manuscript text. J.A.C. helped design the study and wrote the main manuscript text. T.D. co-ordinated and designed the study and wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Coughlan, S., Mulhair, P., Sanders, M. et al. The genome of Leishmania adleri from a mammalian host highlights chromosome fission in Sauroleishmania. Sci Rep 7, 43747 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43747

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43747

This article is cited by

-

Evolution of RNA viruses in trypanosomatids: new insights from the analysis of Sauroleishmania

Parasitology Research (2023)

-

Application of next generation sequencing (NGS) for descriptive analysis of 30 genomes of Leishmania infantum isolates in Middle-North Brazil

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Expression and Purification of Membrane Proteins in Different Hosts

International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics (2020)

-

Comparative genomics of Leishmania (Mundinia)

BMC Genomics (2019)

-

A complete Leishmania donovani reference genome identifies novel genetic variations associated with virulence

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.