Abstract

Waterborne polyaniline (PANI) dispersion has got extensive attention due to its environmental friendliness and good processability, whereas the storage stability and mechanical property have been the challenge for the waterborne PANI composites. Here we prepare for waterborne PANI dispersion through the chemical graft polymerisation of PANI into epichlorohydrin modified poly (vinyl alcohol) (EPVA). In comparison with waterborne PANI dispersion prepared through physical blend and in situ polymerisation, the storage stability of PANI-g-EPVA dispersion is greatly improved and the dispersion keeps stable for one year. In addition, the as-prepared PANI-g-EPVA film displays more uniform and smooth morphology, as well as enhanced phase compatibility. PANI is homogeneously distributed in the EPVA matrix on the nanoscale. PANI-g-EPVA displays different morphology at different aniline content. The electrical conductivity corresponds to 7.3 S/cm when only 30% PANI is incorporated into the composites, and then increases up to 20.83 S/cm with further increase in the aniline content. Simultaneously, the tensile strength increases from 35 MPa to 64 MPa. The as-prepared PANI-g-EPVA dispersion can be directly used as the conductive ink or coatings for cellulose fibre paper to prepare flexible conductive paper with high conductivity and mechanical property, which is also suitable for large scalable production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyaniline (PANI) has got special attention amongst conductive polymers owing to the adjustable conductivity, easy preparation, good environmental stability and unique doping/dedoping mechanism. It has been extensively applied in various fields1, such as portable and wearable/foldable electronics2, capacitor3,4, electromagnetic anticorrosion coatings5, shielding devices6, electrochromic displays7, static electricity dissipation8, and so on. However, its applications were restricted due to its poor solubility, infusibility, poor processability and low mechanical propertiesa9. Therefore, various strategies have been put forward. Improving water dispersibility of PANI has been demonstrated as a approach to improve the processability of PANI. In particular, it is advantageous to the environment protection10,11. The incorporation of appropriate substitutes, such as sulfonic acid, boronic acid and carboxylic groups, at the phenyl rings or nitrogen sites of PANI has turned out to be a simple and effective methodology to improve the solubility of PANI12,13,14. In addition, waterborne PANI dispersion with good stability could be prepared through in situ synthesis of PANI using cellulose nanocrystals or graphene oxide15,16. The copolymerisation of aniline derivatives and aniline is also an alternative approach to prepare self-doped and water-soluble PANI derivative10,17. Morsi et al.10 synthesised self-doped PANI by using aniline and 4-amino benzenesulfonic acid as monomers. Moreover, surfactants are also utilized for the stabilisation of waterbornePANI and polypyrroledispersion, such as poly (N-vinylpyrrolidone), methylcellulose, and polyacrylic acid2,18,19,20. The character of surfactant is crucial to control the dispersion and morphology of nanocomposites21,22.

Although the processability of PANI can be improved by increasing the dispersibility of PANI, the materials made from waterborne PANI dispersions still have defects in mechanical properties and adhesion23. Several approaches have been developed to overcome such defects. For instance, polymer emulsion has been adopted as the matrix to blend with waterborne PANI dispersion to combine the electroactivity of PANI with physical properties of polymer emulsion. Santos et al. obtained waterborne PANI composites by mixing PANI with 10% natural latex andaqueousphytic acid was utilised as dopant, the adhesion and corrosion resistance of composite coating are significantly improved24. On the other hand, electrochemical polymerisation of aniline in aqueous polymer solution is also a good approach25. In order to further increase the compatibility between PANI and polymer matrix, core-shell emulsion polymerisation26,27 and in situ polymerisation2,28,29 are put forward.

As a polymer matrix, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) has attracted more attention because of its advantages including non-toxicity, water-solubility, good chemical stability, toughness and adhesion property, film-forming property and possible coupling of charge transport with the motion of its hydroxyl groups30,31. Moreover, PVA is able to simultaneously functionalise as polymeric stabilizer, co-dopant and matrix31,32,33,34. Arenas et al.35 prepared aqueous suspensions of PVA–PANI nanocomposites by conventional polymerisation of aniline in the presence of PVA solution mixed with either surfactant(sodium dodecyl sulfate) or organic acids used as binary dopants, to improve the solubility and processability of the nanocomposites. Mirmohseni et al.33 prepared the polyaniline composite films by chemical polymerization of aniline in the media containing polyvinyl alcohol. The electrical conductivity of the films greatly increased to 2.5 S/cm with the increase of PANI amount. However, the composite property was impaired due to the presence of hydrophilic groups. Partially phosphorylated poly(vinyl alcohol) (P-PVA), as a phosphoric ester by phosphorylation of PVA with phosphoric acid, exhibits more effective stabilisation, higher water resistance and mechanical property. Chen and Liu36 prepared PANI/P-PVA dispersions by the chemical oxidative polymerisation of aniline in aqueous acidic media containing the P-PVA, which display significant dispersibility in aqueous media. Waterborne epoxy coating containing PANI/P-PVA possesses excellent corrosion protection property. In addition, PVA conjugated with 2-isobutyramidopropanoate (PVA-AI) was also reported as dispersing agent to improve the dispersibility and anticorrosion property of PANI/PVA37. Varakirkkulchai et al.38 obtained P-PVA-PANI/polyacrylate nanoparticles by encapsulating P-PVA-PANI with polyacrylate via emulsifier-free emulsion polymerisation. However, most of researches focus on the physical blend of PVA and PANI and in situ oxidation polymerisation of aniline in PVA solution, and very few studies investigated chemical graft modification to improve the dispersibility and distribution.

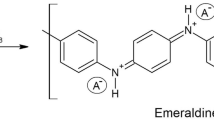

Herein, we report for the first time a facile approach to fabricate an environmental waterborne polyaniline nanocomposite through the chemical graft of PANI into epoxy modified PVA (EPVA) based on the reaction between epoxy groups in PVA and amine groups in PANI, and the epoxy groups are introduced into PVA chain through nucleophilic substitution with epichlorohydrin (ECIP). The molecular design not only inhibits the precipitation of PANI from waterborne polymer matrix and correspondingly improves the stability of waterborne PANI-graft-EPVA dispersion thanks to the formed chemical bond between PANI and EPVA, but also ensures the homogeneous distribution of PANI in PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposites and thereby forms 3D interconnected conducting network with uniformly distributed PANI. The conductivity of PANI-g-EPVA film increases up to 20.83 S/cm with increasing the aniline content to 45%. In general, the conductivity of conventional emeraldine. HCl PANI3 is about 2–10 S/cm, whereas the conductivity of PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite reaches7.3 S/cm with the addition of 30% aniline. The tensile strength increases from 35 MPa to 64 MPa. The as-prepared PANI-g-EPVA dispersion can be directly used as the conductive ink or coatings for cellulose fibre paper to prepare flexible conductive paper with high conductivity and mechanical property.

Results and Discussion

Comparison between in situ PVA/PANI and PANI-g-EPVA

In this study, we prepare PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposites through chemical graft polymerisation, the preparation scheme is shown in Fig. 1a. In order to make comparison between conventional preparation method and chemical graft polymerization, in situ PVA/PANI nanocomposite is also prepared through the oxidation polymerisation of aniline in PVA solution. The optical photos of in situ PVA/PANI and PANI-g-EPVA dispersions and the corresponding films are presented in Fig. 1b. It is found that PANI-g-EPVA film displays more uniform and smooth morphology compared with in situ PVA/PANI film. And macroscopic PANI precipitation was initially generated inside in situ PVA/PANI dispersion after storage for 15 days, and the amount of PANI precipitation increases with prolonging the storage time. In contrast, the PANI-g-EPVA dispersion keeps stable for more than one year, as presented in Fig. 1c. Particle agglomerations are detected in the TEM morphology of in situ PVA/PANI dispersion, and the particle size distributes unevenly. While the particle size of PANI-g-EPVA dispersion is more uniform.

With respect to the chemical graft modification, chemical bonds are built between the PANI and PVA (as shown in the molecular model of PANI-g-EPVA colloidal particles in Fig. 1c), which is favourable to prohibit the PANI aggregation and phase separation. However, as to in situ PVA/PANI, PVA functionalises as stabiliser30,39, PANI oligomers are firstly produced in the early stage of aniline oxidation, and then adsorb at PVA chains. Once the first PANI chain is produced at the stabiliser chain, the aniline oxidation will proceed in close vicinity40. In order to keep the dispersion stable, the hydrophilic PVA stabiliser tends to distribute at the particle surface to form the shell of colloidal particles, and prevents the PANI agglomeration, as shown in Fig. 1c. However, PANI agglomerations take place when the PANI content exceeds certain amount, i.e. the amount of PVA is not high enough to encapsulate the PANI. In addition, the interaction between PANI and PVA is mainly dominated by physical interaction in in-situ PVA/PANI. Phase separation tends to take place as prolonging the storage time, resulting in the agglomeration of PANI, as illustrated in Fig. 1c. Therefore, it can be concluded that building chemical bonds between PANI and other polymer matrix is an effective approach to improve the dispersibility and distribution of PANI in waterborne polymer dispersions, as well as the storage stability of waterborne PANI-g-EPVA dispersion.

Figure 2a shows the surface and cross-section morphology of in situ PVA/PANI and PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite films with 30% aniline content. It is also obvious that PANI homogenously distributes inside the PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite, while PANI coagulation is observed for in situ PVA/PANI. It further certifies that chemical graft modification is able to improve the dispersibility and distribution of PANI in polymer matrix, in comparison with conventional in situ polymerisation.

TG-DTG curves can provide further information on the phase behaviour between PANI and PVA for in situ PVA/PANI and PANI-g-EPVA, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. It is found that in situ PVA/PANI degrades in three steps. The first stage at 85–176 °C is mainly attributed to the removal of water and undopedHCl30. The second stage at 176–307 °C is the superposition of the elimination of side-groups, the H-boned water and the covalent bonds of PVA. The third stage at 360–570 °C is mainly the breakage of the main chains of both polymers (EPVA and PANI)30. However, PANI-g-EPVA shows different degradation behaviours, the two main degradation peaks merge together and only one degradation peak at 362 °C is detected. This suggests good compatibility between PANI and EPVA, and the graft of PANI into PVA chains retards the degradation of PVA chains.

Structure and morphology analysis

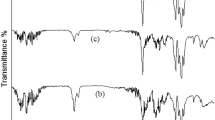

The FTIR spectra (see Supplementary Fig. S1) and 1H-NMR spectra (see Supplementary Fig. S2) of PVA, EPVA, EPVA-aniline and PANI-g-EPVA were provided to demonstrate each reaction step in the preparation process of PANI-g-EPVA. In the FTIR spectrum of PVA, the peaks at 3315 cm−1, 2927 cm−1, 1716 cm−1 and 1076 cm−1 are due to the stretching vibration of –OH, –CH2, C = O and C-O, respectively30,35. A novel peak at 913 cm−1 is observed for EPVA after the nucleophilic substitution with epichlorohydrin, which is corresponding to the characteristic adsorption peak of epoxy group. It suggested that the epoxy groups are successfully incorporated into the PVA chains. The absence of peak at 1716 cm−1 indicates the hydrolysis of ester groups during the process of nucleophilic substitution reaction. The peak at 1664 cm−1 in EPVA spectrum can be ascribed to the deformation vibration of -OH. With the introduction of aniline, the peak at 913 cm−1 corresponding to the adsorption of epoxy groups almost disappeared, certifying the reaction between aniline and EPVA. With the incorporation of PANI, the intensity of -OH adsorption peak decreases, and the peak value shifts to lower wavenumber at 3240 cm−1 due to overlap of the residual -OH groups in EPVA and -NH groups in PANI1,30. The novel peaks at 1656 and 1582 cm−1 are corresponding to the C = C stretching vibration peak of benzene ring and quinone ring in PANI molecule and the C = N stretching vibration peak of quinone ring41. The peaks about 1062 cm−1 is assigned to stretching absorption peaks of in-plane-bending vibration of C–H (mode of N = Q = N, Q = N+H-B, and B-N+H-B; Q = quinoid ring, B = benzenoidring)41,42. The peaks at 1292 cm−1 and 1418 cm−1 are corresponding to the C-N bond stretching vibration in PANI42.

The 1H-NMR spectra of the PVA, EPVA, EPVA-aniline and PANI-g-EPVA are also provided, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S2. In the spectrum of PVA, the triplet signals from 4.19 ppm to 4.65 ppm are attributed to the proton of –OH, which can be attributed to the three spatial stereoregularity of PVA40. With the introduction of epoxy groups, a novel signal appeared at 3.37 ppm, which can be ascribed to the proton of -CH in oxirane43. The signal around 1.77 ppm (-COOCH3) disappeared due to the hydrolysis of ester groups in this step, which is consistent with the FTIR results. In the NMR spectrum of EPVA-aniline, the signals at 7.3–6.4 ppm allow estimation of the presence of aromatic proton signals of aniline44. Then the peak almost disappears as the oxidation polymerization of aniline proceeds. The signals at 3.81 ppm and 6.90–7.31 ppm are the proton of -NH and quinone ring, corresponding to the characteristic adsorption peaks of PANI45. The above results certify that PANI is successfully grafted into PVA matrix and the entire preparation process of PANI-g-EPVA.

The graft efficiency (GE) of PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposites was also determined by elemental analysis. GE value is 52.5%, 48.66%, 41.90% when the aniline content was 20%, 30% and 40%, respectively (see Supplementary Table S1). It indicates that aniline monomers tend to self-polymerization and form free PANI in the PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite with increasing the aniline content. The PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite is probably composed of PANI-g-EPVA, free PANI and free EPVA. The introduction of graft copolymer is beneficial to improve the stability and compatibility between PVA and PANI. The FTIR spectra (see Supplementary Fig. S3) and 1H-NMR spectra (see Supplementary Fig. S4) of PANI-g-EPVA prepared with different aniline content are also provided. The intensity of peaks at 1582 cm−1 and 1292 cm−1 corresponding to the quinone ring and C-N bond stretching vibration in PANI increases when increasing the aniline content from 20% to 30%, and keeps almost invariable with increasing the aniline content from 30% to 40%. The intensity of PANI characteristic signals also displays similar trend as FTIR spectra. It means that the grafted amount of PANI in EPVA increases and then keeps almost constant with increasing aniline content, resulting in the decrease of GE.

In order to further investigate the preparation process and the structure of PANI-g-EPVA dispersion, rheological behaviours of PVA, EPVA, EPVA-aniline and PANI-g-EPVA at each preparation step are studied, as well as the in situ PVA/PANI and PANI-g-EPVA dispersion prepared at different aniline content, as shown in Fig. 3. Rheology has been considered as efficient tool for exploring structural properties and molecular interactions of different materials viz polymer, surfactant, supramolecule etc., in solution, dispersion, stabilized colloid or gel46. Figure 3a shows that the viscosity of EPVA and EPVA-aniline increases with the incorporation of epoxy and aniline groups into PVA chains, which can be ascribed to increased molecular interactions. As increasing the aniline content, the viscosity of EPVA-aniline increases to a certain extent, followed by slight decrease, as shown in Fig. 3c. This suggests that the amount of grafted aniline reaches maximum when the aniline content is 30%, and self-polymerization of aniline monomers tends to take place when aniline content increases to 40%, resulting in the decrease in the amount of grafted aniline in PVA chains. Moreover, the viscosity of PANI-g-EPVA decreases after the oxidation polymerization of aniline owing to the variation in the conformation of polymer chains. As the reaction proceeds, entangled or stretched polymer chains gradually transfer to spherical micelles due to the increase of polymer hydrophobility. The rheology of PANI-g-EPVA is mainly dominated by the interactions among colloidal particles rather than the interactions among polymer chains, and the interaction points among colloidal particles are inevitably decreased in comparison with that among polymer chains, resulting in the decrease in the viscosity.

(a) Steady rheology of PVA, EPVA, EPVA-aniline and PANI-g-EPVA corresponding to each preparation step. (b) Steady rheology of in situ PVA/PANI and PANI-g-EPVA. (c) Steady rheology of EPVA-aniline at different aniline content. (d) Variation of modulus with time for in situ PVA/PANI and PANI-g-EPVA at 80 °C.

Figure 3b displays the steady rheological behaviours of in situ PVA/PANI and PANI-g-EPVA dispersions prepared with 30% aniline content. Although dispersions contain colloidal particles instead of polymers, if we assume the dispersed water droplets slip past each other like the reptation motion of polymer chains the results of polymer analysis can be transferred to dispersions. It is observed that both dispersions present pseudoplastic liquid behaviour47. The viscosity of in situ PVA/PANI is higher at lower shear rate and then keeps decreasing with shear rate. While the viscosity of PANI-g-EPVA decreases firstly and then keeps invariable when the shear rate is greater than 1 s−1. It suggests that the internal network inside in situ PVA/PANI dispersion is unstable compared with PANI-g-EPVA dispersion. This result is also further demonstrated by the oscillatory rheology test, as presented in Fig. 3d. Generally, storage modulus quantifies the mechanical properties of the respective liquids, therefore, it is a measure of the colloidal interactions induced by internal network inside dispersion. With respect to stable dispersion, the interactions among colloidal particles should be able to resist the gravitational force. As presented in Fig. 3d, the storage modulus of in situ PVA/PANI is lower than that of PANI-g-EPVA, and keeps changing due to its unstable inner network structure.

Effects of aniline content on the rheological behaviours of PANI-g-EPVA dispersions were also investigated, as shown in Fig. 4a. With increasing the aniline content from 20% to 30%, the viscosity increases firstly and then decreases when the aniline content reaches 45%. It suggests that the interaction between colloidal particles increases with the incorporation of 30% PANI. However, the interaction is weakened with further increase in the PANI content. At lower aniline content, hydrophobic PANI tends to distribute inside colloidal particles to keep dispersion stable, the surface of colloidal particle is mainly composed of PVA components. With increasing the aniline content, some PANI chains start to distribute on the particle surface and form connected network in the dispersion, leading to the increase of viscosity. However, phase separation takes place when the aniline content increases to 40% owing to the increasing amount of free PANI inside the reaction system, which may be responsible for the decrease of viscosity. Isothermal time dependence of storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) at 80 °C with constant frequency for PANI-g-EPVA dispersions prepared with different aniline content is shown in Fig. 4b. The storage modulus of PANI-g-EPVA with 30% aniline content is the highest, and the ratio of G” to G′ is the lowest, suggesting that PANI-g-EPVA with 30% aniline content behaves more elastically than the other two dispersions. In contrast, the storage modulus of PANI-g-EPVA with 45% aniline content is the lowest, which may be not enough to resist the gravitational stress and therefore cause particle agglomeration. In addition, the storage modulus increases with prolonging the test time. which can be due to the rearrangement of the rod-like colloidal particles.

(a) Effects of aniline content on the steady rheology of PANI-g-EPVA dispersions. (b) Variation of modulus with time for PANI-g-EPVA dispersions prepared with different aniline content. (c) TEM images and (d) Schematic models of the nanostructured PANI-g-EPVA dispersion with different aniline contents.

The TEM images of the PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposites prepared with different aniline contents in the polymerisation are also provided, as shown in Fig. 3. In agreement with rheological behaviour, the colloidal particles interconnect with each other when the aniline content is 30%, resulting in the increase in viscosity. The spherical particles are produced when the aniline content is 20%, the coral-like particles are obtained when the aniline content is 30%, andthe rod-like morphology is formed when the aniline content is 45% (Fig. 4c). TEM results indicate that the morphology of PANI-g-EPVA is directly related to the aniline content. The reactive points in EPVA is settled in this research, the molecular weight of PANI grafted into the EPVA increases as increasing the aniline content (Fig. 4d). At lower aniline content, the EPVA can effectively distributed on the surface of the particles, leading to the formation of spherical shapes. With increasing the aniline content, the molecular weight of grafted PANI increases, and the rigidity of PANI chain is higher than that of EPVA, the mobility of EPVA backbone is thereby restricted to a certain extent, thus coral-like particles are formed by aggregation of particles from their reactive sites. When the aniline content increases to 45%, PANI-g-EPVA chains mainly display rigid characteristic, it is very difficult for the molecular chainsto move and bend, and therefore rod-like particles are obtained through self-assembly of PANI-g-EPVA chains. The schematic models for the formation of PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposites with different morphology are shown in Fig. 4c.

Dynamic light scattering data also show that the average particle diametre (D) increases from 161.7 nm to 1533 nm with increasing the aniline content from 20% to 45%, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S5. The particle size distribution changes from unimodal distribution to bimodal distribution when the aniline content is greater than 30%. It can be attributed to different colloidal particles formed by PANI-g-EPVA and PANI self-aggregations, respectively. This phenomena is consistent with TEM results.

Conductivity, thermal and mechanical property

UV-Vis absorption spectra of PANI-g-EPVA dispersion with different aniline content are shown in Fig. 5a. Three characteristic adsorption bands for doped PANI at wavelength of 300–370 nm, 410–460 nm and 650–800 nm are observed. The absorption band at 300–370 nm is due to the π-π* transitions of benzene ring48,49. The absorption bands at 410–460 nm and 650–800 nm are related to the doping level and polaron-bipolaron transition1,49,50. The intensity of absorption bands increases with increasing the aniline content, and the polaron-bipolaron transition band exhibits a red shift, suggesting the increase in conductivity1.

Conductivity measurements also certify that the electrical conductivity increases from 1.46 × 10−4 to 20.83 S/cm with increasing the aniline content from 5% to 45%, as illustrated in Fig. 5b. The electrical conductivity corresponds to 7.3 S/cm when only 30% PANI is incorporated into the composites, while the conductivity of in situ PVA/PANI composite is only 2.81 S/cm. The tensile strength of PANI-g-EPVA film increases from 35 MPa to 64 MPa, however, the tensile strength presents a declining trend when the aniline content is greater than 30%. When the aniline content is lower than 30%, the PANI is able to homogeneously distribute in the PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite on nanometre scale and thereby functionalize as crosslinking points to increase the molecular interactions due to its high polarity, leading to the increase in tensile strength (Figs 2a and 6a). However, further increase in aniline content from 30% to 45% doesn’t strenghten, but even leads to inferior tensile strength. It can be attributed to the formation of PANI aggregation (in Fig. 6a) inside the nanocomposite film, which can destroy the original crosslinking structure and produce inhomogeneous film with defects, resulting in stress concentration and the decrease of tensile strength.

(a) SEM photographs of the PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite films at different aniline contents. (b) TG thermograms of PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite films at different aniline contents. (c) DTG thermograms of PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite films at different aniline contents: a–0%, b–20%, c–30%, d–40%, e–45%. (d) Storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) as a function of temperature for PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite films at different aniline contents: a–20%, b–30%, c–40%.

SEM morphology (Figs 2a and 6a) demonstrates that smooth and uniform PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite film can be obtained when the aniline content is 30%, which is entirely different from the reported research30,50. In general, PANI aggregations tend to gather on the composite film surface to form inhomogeneous surface30,50. Chen reported that the original structure of phosphorylated PVA disappeared with the incorporation of PANI, and a large amount of the crystals werefound on the surface of PANI/PVA composites30. Whereas the PANI-g-EPVA displays the similar morphology as pure EPVA. This phenomenon further proves that graft polymerisation of PANI into EPVA chains is an effective approach to promote the uniform distribution of PANI in EPVA matrix and the chemical bonds between EPVA and PANI can effectively prohibit the migration of PANI onto the surface of composite films.

To further study the phase behaviour and thermal behaviour of PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposites, the thermogravimetry (TG) and differential thermogravimetry (DTG) thermograms of composite films areinvestigated, as illustrated in Fig. 6b and c. The thermal stability is estimated by the degradation temperature at 10% weight loss (D0.1) and 50% weight loss (D0.5). The pure EPVA undergoes three main degradation steps. The peak at 50–150 °C is ascribed to the elimination of water molecules, the peak at 250–370 °C is due to the breakdown of side groups, and the peak at 370–480 °C is attributed to the breakdown of mainchain30,51,52. With the incorporation of 30% aniline, only one main degradation peak is observed, demonstrating the good compatibility between EPVA and PANI. Withthe incorporation of 30% PANI, D0.1 of PANI-g-EPVA increases from 271 to 313 °C, D0.5 increases from 320 to 359 °C, the thermal stability of EPVA can be greatly improved. However, the thermal stability of PANI-g-EPVA is weakened when the aniline content exceeds 30% due to the weakened molecular interactions caused by phase separation, whereas the degradation temperature is still higher than that of pure EPVA.

Figure 6d shows the temperature dependence of the storage modulus and tan δfor PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposite films. The storage modulus is an indicator of the polymer stiffness, and the temperature at maximum tan δis defined as the glass-transition temperature (Tg)53. It is found that the storage modulus increases with the incorporation of 30% PANI, indicating an increase in the rigidity of composite film54. Since the homogeneous distribution of PANI in PANI-g-EPVA nanocomposites is beneficial for the formation of more uniform network and enhances molecular interactions more effectively, and free PANI inside nanocomposites can also functionalise as a nanoreinforcing agent and crosslinking points in the nanocomposites. It has been demonstrated that enhancing the interaction between nanofillers and polymer matrix is able to increase the mechanical and thermal properties55,56. However, the storage modulus greatly decreases when the aniline content increases to 45%, owing to the weakened intermolecular interaction. It is also observed that the Tg peak shifts to higher temperature and the intensity of tan δ decreases as increasing the aniline content. It indicates that the movement of polymer chains is restricted with the incorporation of PANI.

Surface coating of PANI-g-EPVA dispersion on cellulose fibre paper

The as-prepared PANI-g-EPVA dispersion can be directly used as the conductive ink or coating for cellulose fibre paper to prepare conductive paper, which is suitable for scalable production (Fig. 7a). Due to the porous characteristic of cellulose fiber, the PANI-g-EPVA dispersion is able to penetrate into the fiber to form 3D conductive networks in cellulose fiber paper, the corresponding model is shown in Fig. 7b. The electrical conductivity of conductive paper reaches 1.45 S/cm when the PANI-g-EPVA 3 is adopted. It is also worthy to note that the tensile strength of conductive paper increases from 38.9 to 67.5 KN. m. Kg−1. In our previous reported study, the mechanical property of conductive paper prepared through in situ chemical oxidation polymerisationis generally inferior to the original paper, owing to the acid hydrolysis and the weakened interaction among fibres57,58. Therefore, surface coating is an effective methodology to simultaneously improve the conductivity and mechanical property of conductive paper.

Conclusion

Graft polymerization of aniline into epichlorohydrin modified PVA chain is an effective approach to prepare environmental waterborne polyaniline nanocomposites with high stability, conductivity and mechanical properties. The preparation process have been investigated by FTIR, NMR and rheology. The as-prepared PANI-g-EPVA dispersion keeps stable after storage even after one year. In comparison with physical blend and in situ polymerisation, more uniform and smooth film can be obtained, and the compatibility between PANI and EPVA is also greatly improved. The electrical conductivity of PANI-g-EPVA film reaches 7.3 S/cm when only 30% PANI is incorporated into the composites. The tensile strength, modulus, and thermal stability also get significant improvement. It can be concluded that building chemical bonds between PANI and other polymer matrix is an effective approach to improve the dispersibility and distribution of PANI in waterborne polymer dispersions, as well as the dispersion stability, and thereby produce high-performance nanocomposites. The as-prepared PANI-g-EPVA dispersion can be directly used as the conductive ink or coatings for cellulose fibre paper to prepare conductive paper with high conductivity and mechanical property, which is also suitable for large scalable production. Besides, the as-prepared waterborne PANI dispersion can be also utilised as conductive ink or coatings for other substrates, such as glass, metal and plastics. Moreover, the present strategy to synthesise waterborne PANI nanocomposites could be easily extended to other polymer matrix and be available for other conducting polymers, such as polypyrrole.

Methods

Materials

Poly(vinylalcholol) (PVA:Pn = 0588 ± 50, Mw = 19800–24200) with 88% alcoholysis degree was obtained from Shanghai Yingjia Industrial Development Co., Ltd. Aniline was purchased from Shaanxi Hongyan Chemical Company, China, and purified by double distillation under reduced pressure before use. Ammonium peroxydisulftate (APS, 99.9%), hydrochloric acid (HCl), epoxy chloropropane (ECIP, 99.9%) and potassium hydroxide (KOH, 99.9%) were all analytical grade and supplied by Tianli Chemical Agents Company, China.

Preparation of PANI-graft-PVA dispersion

50 g PVA solution (20%, w/w) was introducedintoa 250 ml three-necked flask, and the pH value was adjusted to 11 with KOH solution. Then4 g ECIP was added to initiate nucleophilic substitution reaction between ECIP and PVA, and epoxy groups were incorporated into PVA side chain. The reaction was kept at 80 °C for 30 min. Afterwards, the pH value was subsequently adjusted to 7, and PVA with epoxy side chains (EPVA) was obtained. Subsequently, aniline of different content was added into the EPVA solution. The reaction between -NH2 in aniline and epoxy groups in EPVA was conducted at 80 °C for 2 h, and then EPVA-aniline was obtained. Afterwards, the reaction system was placed in an ice-water bath, and the pH value was adjusted to 2 with HCl solution. The chemical oxidation polymerisation of aniline was initiated with APS addition. The reaction was maintained for 24 h, and green PANI-graft-EPVA (PANI-g-EPVA) dispersions were thereby obtained. The preparation procedure and optical photos of PANI-g-EPVA dispersions and films were shown in Fig. 1. In addition, in situ PVA/PANI dispersion was prepared by chemical oxidation polymerisation of aniline in unmodified PVA, the optical photos of in situ PVA/PANI were also shown in Fig. 1. The low-molecular-weight compounds inside dispersions were removed by exhaustive dialysis in a dialysis bag against 0.2 M HCl.

Preparation of composite films

The composite films were prepared by casting dispersions into PTFE plate and dried at room temperature for 3 days to obtain conductive composite films.

Characterisations

The products were extracted with acetone in a soxhlet apparatus for 24 h to remove free PANI and physically absorbed PANI and thereby pure PANI-g-EPVA was obtained. The carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen elemental contents of pure PANI-g-EPVA were determined using a Elemental Analyzer (Elemeraor, Vario EL III, Germany). Grafting efficiency (GE) was used to evaluate the graft polymerization of aniline onto EPVA. GE was defined as the ratio of N content by elemental analyzer to the N content calculated by monomer charged. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on an FTIR spectrometer (Bruker Optics Vector-22, Germany) at frequencies of 4000 to 400 cm−1 at a 1 cm−1 resolution, signal-averaged over 32 scans, and baseline-corrected. The 1H-NMR spectra were determined by a nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR, Bruker Avance 400 MHz, Germany). D-Substituted dimethyl sulfoxide was used as a solvent, and tetramethylsilane was used as the internal standard. The morphology of the colloidal particles in dispersion was observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Hitachi S570, Japan) with phosphotungstic acid as a staining agent. The surface morphology of the composite films was observed with an scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Japan). All of the samples were coated with gold in vacuo before SEM observation. The particle size and distribution values of the dispersions were analysed by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS ZEN 3500, United Kingdom). The rheological properties of dispersion were analysed in an American TA Instrument AR2000ex Rheometer. All tests for dispersion were carried out using DIN concentric cylinders geometry. Samples underwent a constant shearing treatment (1 s−1 for 10 min) prior to analysis to remove history effects. The steady measurements were carried out over a range of shear rate from 0.1 to 100 s−1 at 25 °C. The time sweep measurements were done at 80 °C with constant stress and frequency of 0.5 Pa and 6 Hz, respectively. UV-Vis absorption spectra were carried out by using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-265FW, Japan) at room temperature, with scan speed of 40 nm/min, integration time of 2 s and bandwidth of 1 nm. The surface resistivity was determined with a four-point van der Pauw method with a Keithley 237 high-voltage source and a Keithley 2010 multimeter. The surface resistivity was measured by a standard four-probe method. The tensile strength of the PVA/PANI films was evaluated on a TS2000-S universal testing machine (Scientific and Technological Limited Co., High Iron, Taiwan). The measurements were repeated at least five times. Thermal analysis of the samples was performed on a thermogravimetric analyser (TGA, Q500, America) under a nitrogen atmosphere in the temperature range of 25–650 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. Dynamic mechanical analysis was carried out on a Q800 dynamic mechanical analyser (TA Instruments Co.) at a frequency of 2 Hz and heating rate of 3 °C/min over a temperature range from −30 °C to 100 °C.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, H. et al. Facile approach to fabricate waterborne polyaniline nanocomposites with environmental benignity and high physical properties. Sci. Rep. 7, 43694; doi: 10.1038/srep43694 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Bhadra, J., Madi, N. K., Al-Thani, N. J. & Al-Maadeed, M. A. Polyaniline/polyvinyl alcohol blends: Effect of sulfonic acid dopants on microstructural, optical, thermal and electrical properties. Synth. Met. 191, 126–134 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. High-performance flexible solid-state carbon cloth supercapacitors based on highly processible N-graphene doped polyacrylic acid/polyaniline composites. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–10, doi: 10.1038/srep12883 (2016).

Zhang, X., Guox, W. J. & Manohar, S. K. Synthesis of polyaniline nanofibers by “nanofiber seeding”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 4502–4503 (2004).

Liu, S. et al. Patterning two-dimensional free-standing surfaces with mesoporous conducting polymers. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–9, doi: 10.1038/ncomms9817 (2015).

Kamaraj, K., Sathiyanarayanan, S., Muthukrishnan, S. & Venkatachari, G. Corrosion protection of iron by benzoate doped polyaniline containing coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 64, 460–465 (2009).

Chung, D. D. L. Electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of carbon materials. Carbon 39, 279–285 (2001).

Zhao, L., Xu, Y., Qiu, T., Zhi, L. & Shi, G. Polyaniline electrochromic devices with transparent graphene electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 55, 491–497 (2009).

Hopkins, A. R. & Reynolds, J. R. Crystallization Driven Formation of Conducting Polymer Networks in Polymer Blends. Macromolecules 33, 5221–5226 (2000).

Yue, J. et al. Effect of Sulfonic Acid Group on Polyaniline Backbone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 2665–2671 (1991).

Morsi, R. E., Khamis, E. A. & Al-Sabagh, A. M. Polyaniline nanotubes: Facile synthesis, electrochemical, quantum chemical characteristics and corrosion inhibition efficiency. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. E. 35, 568–572 (2015).

Bhandari, H., Choudhary, V. & Dhawan, S. K. Influence of self-doped poly (aniline-co- 4-amino-3-hydroxy-naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid) on corrosion inhibition behaviour of iron in acidic medium. Synth. Met. 161, 753–762 (2011).

Li, X. G., Huang, M. R., Feng, W., Zhu, M. F. & Chen, Y. M. Facile synthesis of highly soluble copolymers and sub-micrometerparticles from ethylaniline with anisidine and sulfoanisidine. Polymer 45, 101–115 (2004).

Chen, X. P. et al. First-principles study of the effect of functional groups on polyaniline backbone. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–7, doi: 10.1038/srep16907 (2015).

Lee, K. et al. Metallic transport in polyaniline. Nature 441, 65–68 (2006).

Wu, X., Lu, C., Xu, H., Zhang, X. & Zhou, Z. Biotemplate synthesis of polyaniline@cellulosenanowhiskers/natural rubber nanocomposites with 3D hierarchical multiscale structure and improved electrical conductivity. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces. 6, 21078–21085 (2014).

Zhou, Z., Zhang, X., Wu, X. & Lu, C. Self-stabilized polyaniline@graphene aqueous colloids for the construction of assembled conductive network in rubber matrix and its chemical sensing application. Compos. Sci. Technol. 125, 1–8 (2016).

Lin, H. K. & Chen, S. A. Synthesis of New Water-Soluble Self-Doped Polyaniline. Macromolecules 33, 8117–8118 (2000).

Sulimenko, T., Stejskal, J., Křivka, I. & Prokeš, J. Conductivity of colloidal polyaniline dispersions. Eur. Polym. J. 37, 219–226 (2001).

Plesu, N., Grozav, I., Iliescu, S. & Ilia, G. Acrylic blends based on polyaniline. Factorial design. Synth. Met. 159, 501–507 (2009).

Geng, Y. H. et al. Water soluble polyaniline and its blend films prepared by aqueous solution casting. Polymer 40, 5723–5727 (1999).

Sun, Z. et al. Rational design of 3D dentritic TiO2 nanostructures with favorable architectures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19314–19317 (2011).

Lee, Y. et al. Hollow Sn-SnO2 nanocrystal/graphite composites and their lithium storage properties. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 4, 3459–3464 (2012).

Deshpande, P. P. et al. Conducting polymers for corrosion protection: a review. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 11, 473–494 (2014).

Santos, L. H. E., Branco, J. S. C., Guimarães, I. S. & Motheo, A. J. Synthesis in phytic acid medium and application as anticorrosive coatings of polyaniline-based materials. Surf. Coat. Technol. 275, 26–31 (2015).

Farhadi, K. et al. Electrochemical preparation of nano-colloidal polyaniline in polyacid matrix and its application to the corrosion protection of 430SS. Synth. Met. 195, 29–35 (2014).

Li, C. Y., Chiu, W. Y. & Don, T. M. Polyurethane/polyaniline and polyurethane-poly(methyl methacrylate)/polyaniline conductive core-shell particles: Preparation, morphology, and conductivity. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 45, 3902–3911 (2007).

Han, M. G. et al. Polyaniline coated poly(butyl methacrylate) core-shell particles: roll-to-roll printing of templated electrically conductive structures. J. Mater. Chem. 17, 1347–1352 (2007).

Pour-Ali, S., Dehghanian, C. & Kosari, A. In situ synthesis of polyaniline-camphorsulfonate particles in an epoxy matrix for corrosion protection of mild steel in NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 85, 204–214 (2014).

Syed, J. A., Tang, S., Lu, H. & Meng, X. Water-soluble polyaniline-polyacrylic acid composites as efficient corrosion inhibitors for 316SS. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 2950–2959 (2015).

Chen, F. & Liu, P. High electrically conductive polyaniline/partially phosphorylated poly(vinyl alcohol) composite films via aqueous dispersions. Macromol. Res. 19, 883–890 (2011).

Min, S. C., Sun, Y. P., Ji, Y. H. & Choi, H. J. Synthesis and Electrical Properties of Polymer Composites with Polyaniline Nanoparticles.Mater. Sci. Eng. C24, 15–18 (2004).

Bhadra, J. & Sarkar, D. Size variation of polyaniline nanoparticles dispersed in polyvinyl alcohol matrix. Bull. Mater. Sci. 33, 519–523 (2010).

Mirmohseni, A. & Wallace, G. G. Preparation and characterization of processable electroactive polyaniline–polyvinyl alcohol composite. Polymer 44, 3523–3528 (2003).

Hermas, A. A., Salam, M. A., Al-Juaid, S. S., Qusti, A. H. & Abdelaal, M. Y. Electrosynthesis and protection role of polyaniline-polyvinylalcohol composite on stainless steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 77, 403–411 (2014).

Arenas, M. C., Sánchez, G., Martínez-Álvarez, O. & Castaño, V. M. Electrical and morphological properties of polyaniline–polyvinyl alcohol in situ nano composites. Composites Part B56, 857–861 (2014).

Chen, F. & Liu, P. Conducting polyaniline nanoparticles and their dispersion for waterborne corrosion protection coatings. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 3, 2674–2702 (2011).

Gao, X. Z., Liu, H. J., Cheng, F. & Chen, Y. Thermoresponsive polyaniline nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization, and their potential application in waterborne anticorrosion coatings. Chem. Eng. J. 283, 682–691 (2016).

Varakirkkulchai, P., Kongparakul, S. & Prasassarakich, P. Polyaniline/polyacrylate core-shell composites: preparation, morphology and anticorrosive properties. Prog. Org. Coat. 85, 84–91 (2015).

Mumtaz, M., Labrugère, C., Cloutet, E. & Cramail, H. Synthesis of Polyaniline Nano-Objects Using Poly(vinyl alcohol)-, Poly(ethylene oxide)-, and Poly[(N-vinyl pyrrolidone)-co-(vinyl alcohol)]- Based Reactive Stabilizers. Langmuir 25, 13569–13580 (2009).

Moritani, T., Kuruma, I., Shibatani, K. & Fujiwara, Y. Tacticity of poly(vinyl alcohol) studied by nuclear magnetic resonance of hydroxyl protons. Macromolecules 5, 577–580 (1972).

Kieffel, Y., Travers, J. P., Ermolieff, A. & Rouchon, D. Thermal aging of undoped polyaniline: Effect of chemical degradation on electrical properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 86, 395–404 (2002).

Hino, T., Namiki, T. & Kuramoto, N. Synthesis and characterization of novel conducting composites of polyaniline prepared in the presence of sodium dodecylsulfonate and several water soluble polymers. Synth. Met. 156, 1327–1332 (2006).

Ahmad, S., Gupta, A. P., Sharmin, E., Alam, M. & Pandey, S. K. Synthesis, characterization and development of high performance siloxane-modified epoxy paints. Prog. Org. Coat. 54, 248–255 (2005).

Lu, J., Moon, K., Kim, B. & Wong, C. P. High dielectric constant polyaniline/spoxy composites via in situ polymerization for embedded capacitor applications. Polymer 48, 1510–1516 (2007).

Swapna, P., Subrahmanya, R. S. & Sathyanarayana, D. N. Water-soluble conductive blends of polyaniline and poly(vinyl alcohol) synthesized by two emulsion pathways. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 98, 583–590 (2005).

Gangopadhyay, R. Exploring properties of polyaniline-SDS dispersion: a rheological approach. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 338, 435–443 (2009).

Oliveira, M. E. R. et al. Preparation and characterization of composite polyaniline/poly(vinyl alcohol)/palygorskite. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 119, 37–46 (2015).

Kim, B. J., Oh, S. G., Han, M. G. & Im, S. S. Synthesis and characterization of polyaniline nanoparticles in SDS micellar solutions. Synth. Met. 122, 297–304 (2001).

Patil, D. S., Shaikh, J. S., Dalavi, D. S., Kalagi, S. S. & Patil, P. S. Chemical synthesis of highly stable PVA/PANI films for supercapacitor application. Mater. Chem. Phys. 128, 449–455 (2011).

Gangopadhyay, R., De, A. & Ghosh, G. Polyaniline-poly(vinyl alcohol) conducting composite: material with easy processability and novel application potential. Synth. Met. 123, 21–31 (2001).

Yang, J. M., Wang, N. C. & Chiu, H. C. Preparation and characterization of poly(vinyl alcohol)/sodium Alginate blended membrane for alkaline solid polymer electrolytes membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 457, 139–148 (2014).

Bartholome, C. et al. Influence of surface functionalization on the thermal and electrical properties of nanotube–PVA composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 68, 2568–2573 (2008).

Wang, H., Niu, Y., Fei, G., Shen, Y. & Lan, J. In-situ polymerization, rheology, morphology and properties of stable alkoxysilane-functionalized poly(urehtane-acrylate) microemulsion. Prog. Org. Coat. 99, 400–411 (2016).

Naidu, B. V. K., Sairam, M., Raju, K. V. S. N. & Aminabhavi, T. M. Pervaporation separation of water + isopropanol mixtures using novelnanocomposite membranes of poly(vinyl alcohol) and polyaniline. J. Membr. Sci. 260, 142–155 (2005).

Gu, J. et al. Functionalized graphite nanoplatelets/epoxy resin nanocomposites with high thermal conductivity. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 92, 15–22 (2016).

Gu, J. et al. Thermal conductivities, mechanical and thermal properties of graphite nanoplatelets/polyphenylene sulfide composites. RSC Adv. 4, 22101–22105 (2014).

Wang, H., Hu, M., Fei, G., Wang, L. & Fan, J. Preparation and characterization of polypyrrole/cellulose fiber conductive composites doped with cationic polyacrylate of different charge density. Cellulose 22, 3305–3319 (2015).

Wang, H. et al. Microstructure, distribution and properties of conductive polypyrrole/cellulose fiber composites. Cellulose 20, 1587–1601 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors kindly acknowledge the support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21544011, 51373091, 21505089), Development Program of Shaanxi Province (No. 2015KJXX-35), Frontier and Key Technological Innovation Special Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2014B090915001), Science and Technology Research and Development Program of Xi’an Weiyang District (No. 201505), and the Project supported by the Key Laboratory of Education Bureau of Shaanxi Province (No. 2011JS057).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H.W., B.H., G.Q.F. and Y.D.S. designed the research. H.H.W. wrote the paper, analyzed and interpreted the data. H.W., Y.L.S. performed the material preparation, characterization and test. All authors participated in discussing and reviewing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Wen, H., Hu, B. et al. Facile approach to fabricate waterborne polyaniline nanocomposites with environmental benignity and high physical properties. Sci Rep 7, 43694 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43694

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43694

This article is cited by

-

Structural investigation and optical characteristics of low-energy hydrogen beam irradiated polyvinyl alcohol/polyaniline composite materials

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2023)

-

The interplay of chemical structure, physical properties, and structural design as a tool to modulate the properties of melanins within mesopores

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Structural, electrical, and photocatalytic investigations of PANI/ZnO nanocomposites

Ionics (2021)

-

Synthesis and Optical Properties of PVA/PANI/Ag Nanocomposite films

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2020)

-

Benzimidazole-based dendritic nanofiltration membranes

Iranian Polymer Journal (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.