Abstract

Emerging diseases have been increasingly associated with population declines, with co-infections exhibiting many types of interactions. The chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) and ranaviruses have extraordinarily broad host ranges, however co-infection dynamics have been largely overlooked. We investigated the pattern of co-occurrence of these two pathogens in an amphibian assemblage in Serra da Estrela (Portugal). The detection of chytridiomycosis in Portugal was linked to population declines of midwife-toads (Alytes obstetricans). The asynchronous and subsequent emergence of a second pathogen - ranavirus - caused episodes of lethal ranavirosis. Chytrid effects were limited to high altitudes and a single host, while ranavirus was highly pathogenic across multiple hosts, life-stages and altitudinal range. This new strain (Portuguese newt and toad ranavirus – member of the CMTV clade) caused annual mass die-offs, similar in host range and rapidity of declines to other locations in Iberia affected by CMTV-like ranaviruses. However, ranavirus was not always associated with disease, mortality and declines, contrasting with previous reports on Iberian CMTV-like ranavirosis. We found little evidence that pre-existing chytrid emergence was associated with ranavirus and the emergence of ranavirosis. Despite the lack of cumulative or amplified effects, ranavirus drove declines of host assemblages and changed host community composition and structure, posing a grave threat to all amphibian populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Geographic ranges of pathogens are dynamic, generating novel interactions with potential host species and their existing pathogens1,2,3. The outcomes of these processes for host populations are difficult to forecast since the effects on the likelihood of disease are unpredictable4,5,6. Most of our understanding of the nature of multi-pathogen interactions in multi-host communities is derived from experimental evidence, or inferred from cross-sectional studies of infections within a host community7,8. Longitudinal studies of co-infection dynamics in wild animal host communities are exceptional (e.g. refs 5 and 9) and even then, the initiation of a two-pathogen interaction is almost never captured by field studies. Data on the latter would be of great interest, as experimental evidence shows that the point at which the interaction is initiated can significantly affect disease outcomes and demography of host populations10,11.

Biodiversity is increasingly threatened by infectious disease emergence associated with rapid population declines12,13,14,15. Most of these are multi-host pathogens, none more so than the amphibian-associated chytridomycete fungi and ranaviruses. These pathogens have an extraordinarily broad host range, infecting dozens of amphibian species and, in the case of the ranaviruses, reptile and fish hosts as well16,17. Both are responsible for amphibian mass mortality events across the globe, many of which involve multiple host species12,13,18,19. However, not all cases of ranavirosis and chytridiomycosis affect a broad host range20,21,22,23,24,25 and many host populations sustain recurring mortality events without any evidence of demographic decline, or even carry infections without overt signs of disease21,23,26. Variation of pathogenic effects and virulence have been attributed to host and pathogen genotypes27, environmental factors28 and variation of host immunity (e.g. ref. 29), but what is increasingly recognized is that these two pathogen groups commonly overlap in range and co-infect amphibian hosts30,31,32,33. These cross-sectional studies raise the question as to whether impacts on host populations and communities are caused by one or the other pathogen group, or both34,35. Notwithstanding, the majority of studies focus exclusively on one or the other pathogen group and, as a result, co-infection dynamics are being understudied33,36.

Iberia is Europe’s worst affected region given the serious outcomes that have arisen from the lethal forms of both diseases13,23,37. Chytridiomycosis attributable to infection with Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) has been assessed to some degree and shown to be a risk to Iberian amphibian host species, but only in the context of single pathogen effects23,24,28,37,38,39,40,41,42. Recently, cases of lethal ranavirosis that have emerged in the region are responsible for amphibian host community collapses13. Again, these cases are considered only from the single pathogen perspective, but do suggest that lethal ranavirosis is an emerging disease in Iberia and show that this pathogen affects the same hosts as lethal chytridiomycosis in the region.

We previously reported lethal chytridiomycosis responsible for mass mortality of common midwife toads (Alytes obstetricans) inhabiting Serra da Estrela, Portugal24. Since then we have been monitoring amphibian communities in the area and here report the emergence of lethal ranavirosis in the same region. This allowed us the novel opportunity to ascertain the distribution of the two pathogens in amphibian assemblages in Serra da Estrela. In turn, by closely monitoring index sites for emergent ranavirosis, we perform both quantitative and qualitative assessments of the impact of infectious disease on host communities in the presence of one (Bd) or both pathogens. Here we report the results of these surveys, spanning six years of surveillance, where we documented sequential emergence of lethal chytridiomycosis and ranavirosis.

Results

Up until the summer of 2011, all the mortality events at Serra da Estrela Natural Park were only associated with the presence of Bd. Alytes obstetricans metamorphs dying at high elevation sites (above 1200 m) were confirmed to be infected with Bd and often dying as a result24. Although Bd was present at both Sazes and Folgosinho, we did not detect mortality clearly attributable to chytridiomycosis at these locations during this study. Only 5.7% (3/53) of dead Lissotriton boscai and just 4.4% (4/92) of all newts, live or dead, tested positive for Bd at Folgosinho across all years. Prevalence of infection of overwintering larvae of Alytes never exceeded 33.3%. No Salamandra tested positive for Bd and only two Triturus marmoratus tested positive at Folgosinho (Table S3).

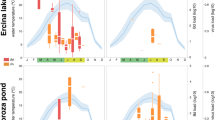

Prevalence of infection with Bd varied between species (L. boscai and A. obstetricans) at Folgosinho and Sazes (F = 5.91, df = 1, 15, P = 0.0334), but not over time (F = 4.32, df = 1, 15, P = 0.0620) nor across the two study sites (F = 1.35, df = 1, 15, P = 0.2698; Fig. 1, Table S3). The presence/emergence of ranavirus was not a predictor of Bd variance (F = 0.23, df = 1, 15, P = 0.6449).

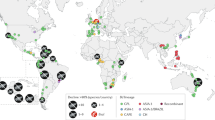

Ranavirus infections were detected throughout Serra da Estrela Natural Park, despite small sample sizes for some of the sites (Fig. 2; Table S3). Prior to the summer of 2011, we never encountered dead amphibians that tested positive for ranavirus through molecular analyses or that presented overt signs of ranavirosis. We first detected infection with ranavirus in August of 2011, when two live adult T. marmoratus sampled at Folgosinho and several species sampled at Represa da Torre tested positive by PCR (Table S3). At that time mortality was observed in recently metamorphosed individuals of Alytes obstetricans and Bufo spinosus. When we returned to Folgosinho in November of that same year, 92.3% of the Bosca’s newts found at the site were dead and exhibited overt signs of ranavirosis. Sick/moribund and dead animals exhibited skin haemorrhages on their ventral body surfaces, ulcerations and, in a few cases, limb necrosis - all gross signs typical of lethal ranavirosis (Fig. 343). Tissues were necrotic, with cells in cytolysis with only nuclei remaining, severely limiting the examination. Nevertheless, we could see that the skins of necropsied individuals presented greyish foci and focal erythema associated with enlarged, mottled pale brown and friable livers. Mortality of L. boscai was recorded across all life stages and ages making use of the aquatic environment (Fig. S1). Ranavirus prevalence as determined using PCR was extremely high (96% for L. boscai, and 90% across all species; Table 1, S1). The same pattern of mass mortality, involving multiple amphibian species, was repeated annually across all four seasons at Folgosinho. Each year we encountered numerous dead and/or dying adult and larval caudates (L. boscai, T. marmoratus and S. salamandra) and A. obstetricans. In addition to Represa da Torre and Folgosinho, we observed and confirmed lethal ranavirosis at two other locations in the park (Fig. 2, Table S3). Here, A. obstetricans of all life history stages were found dead or dying and exhibiting clinical signs of ranavirosis, and ranavirus infection was confirmed with molecular diagnostics. However, many of these animals also tested positive for infection with Bd (Fig. 4; Table S3). Co-infections were detected in Hyla molleri, B. spinosus and L. boscai. Lethal chytridiomycosis had previously caused mass mortality of A. obstetricans at all three of these higher elevation locations, but lethal disease had only been reported to affect recently metamorphosed juveniles24. By comparison, we recorded only 4/233 ranavirus-infected individuals at Sazes over the same time span (Table S3) and never observed any overt signs of disease.

Abbreviations key: BEF, Barragem da Erva da Fome; LCQ, Lagoa do Covão das Quelhas; LCS, Lagoa dos Cântaros; PSC, Pedreira de Santa Comba de Seia; RTR, Represa da Torre; RSZ, Repreza de Sazes; SGD, Salgadeiras; FGS, Tanque de Folgosinho; TAL, Tanque do Alvoco; SFS, Tanque dos Serviços Florestais de Sazes. Points on the map were generated using QGis 2.0 (Quantum GIS Development Team, 2013) and edited in Adobe PhotoShop CS6 (Adobe, 2012).

We found a highly significant effect of time on abundance for most of the species at Folgosinho, where those experienced a sharp decline coinciding with the first outbreaks of ranavirosis (Fig. 5; Table 1). As an example, the adult population of L. boscai declined by 45.5% between 2011 and 2012, and 68.8% between 2011 and 2013 (Fig. 5). In the spring of 2014 the Folgosinho tank was emptied, dramatically disturbing the amphibian community one month before our survey, thus compromising interpretation of population trends for 2013–2014. Nevertheless, abundance of three amphibian species experiencing lethal ranavirosis at this location declined by a minimum of 70%, and almost 100% for L. boscai and A. obstetricans when compared to 2011, before the ranavirosis outbreak (Fig. 5). Despite evidence of infection in S. salamandra (prevalence 5.3% across all years, Table S3) and our failure to detect high numbers of larvae of this species (Fig. 5), the density of S. salamandra larvae did not change significantly from 2011–2013. At Sazes, species trends fluctuated, but never exhibited the clear pattern of decline observed at Folgosinho (Fig. 5; Table 1).

At Folgosinho density per species after 2011 significantly decreases coincidentally with yearly outbreaks of ranaviruses, while density fluctuations of an assemblage at Sazes where outbreaks have not been recorded show no such pattern. Life history stage varied with species but was consistent for each site across years: Alytes obstetricans (overwintering larvae), Lissotriton boscai (adults), Triturus marmoratus (adults) and Salamandra salamandra (larvae).

Virus sequences were predominantly 100% identical to each other across all sequenced genes, and consistent with the recently identified Portuguese newt and toad ranavirus (PNTRV)45. Node support was high across our tree for clades involving viruses from this study. PNTRV clustered unambiguously in the “CMTV-like” group, the sister taxa to Bosca’s newt virus (BNV) isolated from newts that died from ranavirosis in Galicia, Spain (Fig. 6).

Portuguese newt and toad ranavirus (PNTRV) relationships to other known Iberian ranaviruses of wild herpetofauna. Year of first observed outbreaks of CMTV-like ranaviruses (green), FV3-like ranaviruses (red) and an undetermined lineage (yellow). PNTRV infecting amphibians is embedded in the CMTV-like clade, while LMRV has been found in Serra da Estrela population of Iberolacerta monticola and is part of the FV3-like group. Phylogeny constructed from concatenated alignments of six partial genes (see main text). The final concatenated alignment was 2015 bp in length. Node support values were annotated on the best maximum-likelihood tree and were calculated using maximum likelihood (100 bootstraps, black) and Bayesian inference (posterior probabilities as percentage, red). Scale of branch lengths is in nucleotide substitutions per site. Abbreviations key: FGS, Tanque de Folgosinho; LCS, Lagoa dos Cântaros; RTR, Represa da Torre; LCQ, Lagoa do Covão das Quelhas. Points on the map were generated using QGis 2.0 (Quantum GIS Development Team, 2013) and edited on Adobe PhotoShop CS6 (Adobe, 2012).

Discussion

Common midwife toads (A. obstetricans) across Serra da Estrela Natural Park experienced significant population loss prior to 2009, when lethal chytridiomycosis was first detected affecting the species in the park24. Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis was already widespread in the area and declines due to chytridiomycosis were proposed as the cause of population losses24. Ranaviruses were unlikely to have played a role in local extirpation of Alytes before 2011, as carcasses subjected to post mortem examination in 2009 and 2010 and diagnosed with chytridiomycosis did not exhibit signs of ranavirosis24. Instead we first detected the presence of a CMTV-like ranavirus coincidentally with the emergence of lethal ranavirosis later in 2011. Whilst we cannot say exactly when Bd entered the Serra da Estrela, we are confident that lethal chytridiomycosis emerged at least two years before ranavirosis impacted on the system.

Mortality events attributable to chytridiomycosis in the absence of ranavirosis in the park involved only recently metamorphosed A. obstetricans, although other species were found infected and carcasses of two adult Pelophylax perezi collected in 2010 were heavily infected with Bd24. Age-specific mortality of A. obstetricans is consistent with findings across Iberia23,37 and the narrow range of host impacts by Bd on amphibians at Serra da Estrela fits with the findings of a recent risk assessment of European amphibians. In that study Alytes species were consistently ranked at high risk of infection, while green frogs tended to exhibit prevalence equivalent to background levels40.

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and ranaviruses are known to co-occur and share hosts in amphibian assemblages but attempts to disentangle their interaction and impacts on multi-host communities are not well-described in the literature (refs 46 and 47, but see ref. 32). The negative impacts of lethal ranavirosis we observed in Serra da Estrela were consistent with observations at other locations in Iberia in terms of host range, rapidity of host declines and pathogen genotype (Table S3, Figs 3, 4, 5, 613,48). The phylogenetic relationships of Iberian CMTV-like viruses also appear to reflect geographic patterns; PNTRV’s closest relative is BNV from the region of Spain bordering Portugal. In any case, where these patterns manifested, we could find little evidence that the pre-existing Bd infection had an influence on the presence and prevalence of ranavirus infection and the emergence of ranavirosis. Presence of infection with Bd and lethal chytridiomycosis was associated with a variety of patterns of ranavirus infection and disease: high levels of co-infection were associated with significant mortality in Alytes metamorphs at Repressa da Torre; both pathogens also exhibited low prevalence in association with very low levels of mortality in Alytes at Tanque de Sazes; Bd circulated at low prevalence but mortality was only associated with ranavirus infection and affected all species present at Tanque de Folgosinho.

It is the observations at Sazes that shift the perspective on ranavirosis in Iberia. Previous to this, Iberian outbreaks of CMTV-like ranaviruses have shown a close association between infection, mortality and multi-host decline suggestive of rapid range expansion and pathogen amplification through a host community after pathogen invasion (Fig. 513). While we have described apparent rapid range expansion in the park (Fig. 2) and observed amplification after invasion associated with mortality events (e.g. Folgosinho and Represa da Torre), infrequent CMTV-like virus infections have been circulating at Tanque de Sazes since at least 2012 without extensive amplification within the community and no evidence of lethal disease (Fig. 5; Table S3). Again, we could find no clear support for an effect of Bd on differences in amplification in the host community and broad patterns of infection and disease. For example, the species hardest hit by ranavirosis at Folgosinho (Bosca’s newt) was rarely and only weakly infected with Bd (Table 1, S1, Fig. 5) and prevalence of Bd did not differ between Folgosinho and Sazes in this species (Fig. 2). We cannot exclude the hypothesis of altitude playing a role on the different patterns found between these two sites (Sazes is <100 m below Folgosinho). This variable has been shown to be a limiting factor in Bd host-pathogen systems23,24.

Although we could not discern any clear pattern of interaction between pre-existing infections with Bd and the emergence of CMTV-like ranaviruses in Serra da Estrela Natural Park, their cumulative impacts threaten amphibian communities in the park. Whereas previously the impacts of lethal chytridiomycosis were species- and age-specific, mortality now impacts hosts across all aquatic life history stages (Table S3; Fig. S1) and can drive host communities into precipitous declines (Table 1; Fig. 5). Lethal ranavirosis has increased the number of species threatened with disease-driven declines by at least a factor of four. Greer et al.49 suggested that the extinction of tiger salamanders as a result of virulent Ambystoma tigrinum virus (ATV) was unlikely, with larval salamander populations decreasing and then recovering after ATV-driven epidemics. However, even if PNTRV cannot drive hosts to extinction in Serra de Estrela, we have shown that it severely reduced population sizes to the point where hosts became highly vulnerable to stochastic events50: one month after the pond of Folgosinho was cleaned in spring 2014, we only found five adult Bosca’s newts during the breeding season (compared to 228 in 2011) and no overwintered Alytes larvae (compared to 126 in 2011).

Although sharp population declines have been observed in all CMTV-like ranavirus outbreaks in Iberia in recent years, host heterogeneity may play an important role in disease dynamics. While ATV can affect ambystomids in North America (e.g. refs 21 and 51) and a similar outcome has been observed in the UK where FV3-like viruses have caused Rana temporaria declines22, in Iberia we observed entire amphibian assemblages crashing (e.g. ref. 13; this study). These emerging events are taking place in communities that include multiple species from different ectothermic vertebrate classes13. Brenes et al.52 showed experimentally that reptiles and fish live with subclinical infections and therefore might serve as reservoirs for ranaviruses. Equally, non-lethal infections have been documented in lizards (Iberolacerta monticola) in Serra da Estrela53. Although the virus strain (Lacerta monticolaranavirus, LMRV) detected in lizards is genetically differentiated from the virus we described and has yet to be detected in amphibians in the park, the role of these lizards in PNTRV persistence, plus emergence of a new strain is unclear. However, transmission is possible between different species and vertebrate classes54. Emerging hyper-virulent Ranavirus strains (e.g. CMTV-like) might in this way take advantage of naïve hosts easing spill-over and species jumps - for example, marbled newts have been reported to prey on Bosca’s newts in our system55. This poses an additional threat to all lower vertebrates associated with aquatic habitats, including endemic freshwater fish only found in specific sites in Iberia56.

Significant efforts are underway to develop methods to mitigate chytridiomycosis in European amphibians (e.g. ref. 57), but we know of no successful strategy to manage ranavirus infections in captive or wild amphibian populations. CMTV-like ranaviruses and lethal ranavirosis rapidly expand locally (ref. 13; this study) and are extending their reach across Iberia (Fig. 5), home to much of Europe’s amphibian biodiversity, including several endemic species58. Unlike other areas on the peninsula affected by CMTV-like ranaviruses, Serra da Estrela Natural Park may hold the key for developing mitigation against this pathogen group. We are the first to describe diverse amphibian communities in Iberia with low-prevalence, circulating CMTV-like virus infections and our hope is that these provide information that can be used to develop real-world solutions for combating amphibian declines caused by ranavirosis.

Methods

Study sites and survey design

Serra da Estrela is the highest mountain in the Portuguese mainland territory (maximum altitude 1993 m). It is an extension of the Iberian Sistema Central, located in the eastern part of north-central Portugal59,60, and comprises the largest protected area in Portugal, Serra da Estrela Natural Park (PNSE; Fig. 2). We surveyed for Bd and ranavirus infections in all amphibian species found at 10 locations predominantly located within the park, starting in 2010 and focusing on locations where amphibian mortality events were observed. Specifically, in 2010 we opportunistically sampled live and dead amphibians once in sites where Bd had been detected (Table S3; ref. 24). From 2011 onwards we focused our structured field study on two mid-elevation sites with similar geo-climatic features. The first, Folgosinho, is a 255 m2 tank located 1079 m a.s.l. where, in 2011, we observed an amphibian mass mortality event. For comparison, we sampled Sazes, a 50 m2 tank at 985 m a.s.l. with similar habitat features but where we never observed mass mortality events. Both are constantly fed with spring water, and both are approximately 1.5 meters deep. We sampled the two focal sites three to four times per year (once in spring, summer, autumn and, depending on the weather, also winter) for two to three days (each time) using a standardized effort (2 persons/2 hours/day/site). We sampled a maximum of 3 meters from the pond margin using 50 cm dip nets. Other areas of the natural park were also surveyed opportunistically, dip netting between 1 and 2 hours (Fig. 2; Table S3; see ref. 24).

We recorded visible signs of disease for both ranavirosis (see e.g. refs 13 and 26) and chytridiomycosis61. All live specimens were skin swabbed for Bd screening62,63 and we collected a small piece of tail tissue or toe clip, which was stored in 70% ethanol for ranavirus screening - using PCR64 – and skeletochronology (Further details are provided in Supplementary information, SI Appendix). Before release, we applied antiseptic and pain relieving solution (Bactine®, Bayer, USA) to the clipped toes as an analgesic and disinfectant65. We took liver and skin tissue samples from corpses and stored them in 90% ethanol for respective molecular detection of ranavirus and Bd. A selected number of carcasses collected during the first outbreak were stored in 70% ethanol for post-mortem analyses.

Water quality analyses were not indicative of environmental contamination66. To reduce the risk of spreading pathogens across sites, we used disposable vinyl gloves to handle animals and disinfected field equipment and hiking boots in a 1% solution of Virkon® (Antec International ltd., Sudbury, Suffolk, UK) between sites67.

Disease screening, Ranavirus sequencing and phylogenetics

Dead Bosca’s newts were necropsied, although examination was impaired by the advanced autolysis of some animals. Histological examination of tissue samples was attempted after fixation in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin.

We extracted DNA from tissue samples (skin and liver) using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Swabs and skin extractions were screened for the presence of Bd using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), following the protocol of Boyle et al.68. PCR to detect Ranavirus was performed on the DNA samples using the MCP4 and 5 primers targeting the viral MCP gene (CMTV ORF 16L; major capsid protein; AFA44920) as described by Mao et al.69. Samples that tested positive for Ranavirus were subjected to additional PCR reactions to amplify partial sequences from CMTV ORFs 22L (GenBank accession number AFA44926), 58L (AFA44964), 59R (AFA44965), 82L (AFA44988), and a region covering a noncoding sequence and the start of 13R (AFA44917) (see Table S1). PCR amplicons were submitted to Beckman Coulter Genomics for Sanger sequencing of both DNA strands. Additional sequences were downloaded from GenBank (see Table S2).

We visually confirmed base calls by examining electropherograms in CodonCode Aligner (http://www.codoncode.com/aligner/). Forward sequences were reverse complemented and aligned to reverse sequences using PRANK v.10080270. The aligned forward and reverse sequences for each sample were then viewed in Jalview 2.871 and ambiguous base calls were corrected with reference to the electrophoretograms of both sequences. Sequences were aligned to published Ranavirus sequences downloaded from the NCBI nucleotide database, again using PRANK with default settings. All gaps were removed from the alignments with trimAl72 prior to concatenation with PhyUtility73. Trees were constructed from a partitioned alignment using both MrBayes 3.2.274 and RAxML75 with the GTR model of nucleotide substitution and rate variation among sites modelled by a discrete gamma distribution with four categories. We ran MrBayes for 750000 generations with default settings (4 chains, 2 runs, sample frequency = 500, and a 25% burn-in). Twenty maximum-likelihood trees were generated on distinct starting trees in RAxML. Node support values (posterior probabilities [Mr. Bayes] and 100 bootstraps [RAxML]) were annotated on the best maximum-likelihood tree.

Statistical analysis

We selected L. boscai and A. obstetricans (the two most abundant species) to assess variation in the prevalence of Bd over time per site and within sites using a general linear model (GLM), with prevalence of ranavirus as covariate (JMP PRO 12.0; SAS Institute Inc). Accounting for the ranavirus emergence and prevalence allowed understanding the contribution of this second pathogen to the variation on Bd prevalence.

Density was calculated using maximum abundance on a single day per life stage per sampling season and dividing it by the area of the aquatic habitat (highest n/area). Time series of counts were analysed for overall trends in population size using Poisson regression (log-linear models76) with the software TRIM3.077. We used the linear trend model with all years as change points, except for years with no observations. We plotted overall trend estimates for A. obstetricans larvae, L. boscai adults, S. salamandra larvae and T. marmoratus adults, calculated as the slope of the regression line through the logarithms of the indices over the whole study period. We used 95% confidence intervals of the overall trend estimate to test for significant population trends for each species (=slope + /−1.96 times the standard error of the slope78). We followed trend classification proposed by van Strien et al.44 where (e.g.) “substantial decline/steep decline” represents a decline significantly more than 5% per year (5% would mean a halving in abundance within 15 years), and “uncertain” is no evidence of a significant increase or decline in the population, or if trends are less than 5% per year.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Rosa, G.M. et al. Impact of asynchronous emergence of two lethal pathogens on amphibian assemblages. Sci. Rep. 7, 43260; doi: 10.1038/srep43260 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Daszak, P., Cunningham, A. A. & Hyatt, A. D. Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife—threats to biodiversity and human health. Science 287, 443–449 (2000).

Jones, K. E., Patel, N. G., Levy, M. A., Storeygard, A., Balk, D., Gittleman, J. L. & DaszaK, P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–993 (2008).

Telfer, S. & Brown, K. The effects of invasion on parasite dynamics and communities. Funct. Ecol. 26, 1288–1299 (2012).

Brown, S. P., Hochberg, M. E. & Grenfell, B. T. Does multiple infection select for raised virulence? Trends Microbiol. 10, 401–405 (2002).

Telfer, S., Lambin, X., Birtles, R., Beldomenico, P., Burthe, S., Paterson, S. & Begon, M. Species interactions in a parasite community drive infection risk in a wildlife population. Science 330, 243–246 (2010).

Leggett, H. C., Benmayor, R., Hodgson, D. J. & Buckling, A. Experimental evolution of adaptive phenotypic plasticity in a parasite. Curr. Biol. 23, 139–142 (2013).

Johnson, P. T. J. & Hoverman, J. T. Parasite diversity and coinfection determine pathogen infection success and host fitness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 9006–9011 (2012).

Johnson, P. T. J., Preston, D. L., Hoverman, J. T. & LaFonte, B. E. Host and parasite diversity jointly control disease in complex communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 16916–16921 (2013).

Telfer, S., Birtles, R., Bennett, M., Lambin, X., Paterson, S. & Begon, M. Parasite interactions in natural populations: insights from longitudinal data. Parasitology 135, 767–781 (2008).

Balmer, O., Stearns, S. C., Schötzau, A. & Brun, R. Intraspecific competition between co-infecting parasite strains enhances host survival in African trypanosomes. Ecology 90, 3367–3378 (2009).

Natsopoulou, M. E., McMahon, D. P., Doublet, V., Bryden, J. & Paxton, P. J. Interspecific competition in honeybee intracellular gut parasites is asymmetric and favours spread of an emerging infectious disease. P. Roy. Soc. Lond. B Bio. 282, 20141896 (2015).

Lips, K. R., Brem, F., Brenes, R., Reeve, J. D., Alford, R. A., Voyles, J., Carey, C., Livo, L., Pessier, A. P. & Collins, J. P. Emerging infectious disease and the loss of biodiversity in a Neotropical amphibian community. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 3165–3170 (2006).

Price, S. J., Garner, T. W. J., Nichols, R. A., Balloux, F., Ayres, C., Mora-Cabello de Alba, A. & Bosch, J. Collapse of amphibian communities due to an introduced Ranavirus. Curr. Biol. 24, 2586–2591 (2014).

Allender, M. C., Raudabaugh, D. B., Gleason, F. H. & Miller, A. N. The natural history, ecology, and epidemiology of Ophidiomyces ophidiicola and its potential impact on free-ranging snake populations. Fungal Ecol. 17, 187–196 (2015).

Mallon, D. P. From feast to famine on the steppes. Oryx 50, 189–190 (2016).

Duffus, A. L. J. & Cunningham, A. A. Major disease threats to European amphibians. Herpetological Journal 20, 117–127 (2010).

Chinchar, V. G. & Waltzek, T. B. Ranaviruses: Not just for frogs. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1003850 (2014).

Berger, L., Speare, R., Daszak, P., Green, D. E., Cunningham, A. A., Goggin, C. L., Slocombe, R., Ragan, M. A., Hyatt, A. D., McDonald, K. R., Hines, H. B., Lips, K. R., Marantelli, G. & Parkes, H. Chytridiomycosis causes amphibian mortality associated with population declines in the rain forests of Australia and Central America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 9031–9036 (1998).

Duffus, A. L. J., Pauli, B. D., Wozney, K., Brunetti, C. R. & Berrill, M. Frog virus 3-like infections in aquatic amphibian communties. J. Wildl. Dis. 44, 109–120 (2008).

Fellers, G. M., Green, D. E. & Longcore, J. E. Oral chytridiomycosis in the mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa). Copeia 2001, 945–953 (2001).

Brunner, J. L., Schock, D. M., Davidson, E. W. & Collins, J. P. Intraspecific reservoirs: complex life history and the persistence of a lethal Ranavirus. Ecology 85, 560–566 (2004).

Teacher, A. G. F., Cunningham, A. A. & Garner, T. W. J. Assessing the long-term impact of Ranavirus infection in wild common frog populations. Anim. Conserv. 13, 514–522 (2010).

Walker, S. F., Bosch, J., Gomez, V., Garner, T. W. J., Cunningham, A. A., Schmeller, D. S., Ninyerola, M., Henk, D., Ginestet, C., Arthur, C. P. & Fisher, M. F. Factors driving pathogenicity vs. prevalence of amphibian panzootic chytridiomycosis in Iberia. Ecol. Lett. 13, 372–382 (2010).

Rosa, G. M., Anza, I., Moreira, P. L., Conde, J., Martins, F. & Fisher, M. C., Bosch, J. Evidence of chytrid-mediated population declines in common midwife toad in Serra da Estrela, Portugal. Anim. Conserv. 16, 306–315 (2013).

Duffus, A. L. J., Nichols, R. A. & Garner, T. W. J. Experimental evidence in support of single host maintenance of a multihost pathogen. Ecosphere 5, 142 (2014).

Greer, A. L., Berrill, M. & Wilson, P. J. Five amphibian mortality events associated with Ranavirus infection in south central Ontario, Canada. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 67, 9–14 (2005).

Farrer, R. A., Weinert, L. A., Bielby, J., Garner, T. W. J., Balloux, F., Clare, F., Bosch, J., Cunningham, A. A., Weldon, C., du Preez, L. H., Anderson, L., Kosakovsky Pond, S. L., Shahar-Golan, R., Henk, D. A. & Fisher, M. C. Multiple emergences of amphibian chytridiomycosis include a globalised hypervirulent recombinant lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 18732–18736 (2011).

Bosch, J., Carrascal, L. M., Duran, L., Walker, S. & Fisher, M. C. Climate change and outbreaks of amphibian chytridiomycosis in a montane area of Central Spain: is there a link? P. Roy. Soc. Lond. B Bio. 274, 253–260 (2007).

Savage, A. E. & Zamudio, K. R. Adaptive tolerance to a pathogenic fungus drives major histocompatibility complex evolution in natural amphibian populations. P. Roy. Soc. Lond. B Bio. 283, 20153115 (2016).

Green, D. E., Converse, K. A. & Schrader, A. K. Epizootiology of sixty-four amphibian morbidity and mortality events in the USA, 1996–2001. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 969, 323–339 (2002).

Hoverman, J. T., Mihaljevic, J. R., Richgels, K. L. D., Kerby, J. L. & Johnson, P. T. J. Widespread co-occurrence of virulent pathogens within California amphibian communities. EcoHealth 9, 288–292 (2012).

Rothermel, B. B., Miller, D. L., Travis, E. R., McGuire, J. L. G., Jensen, J. B. & Yabsley, M. J. Disease dynamics of red-spotted newts and their anuran prey in a montane pond community. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 118, 113–127 (2016).

Warne, R. W., LaBumbard, B., LaGrange, S., Vredenburg, V. T. & Catenazzi, A. Co-infection by chytrid fungus and ranaviruses in wild and harvested frogs in the tropical Andes. PLoS ONE 11, e0145864 (2016).

Martel, A., Fard, M. S., Van Rooij, P., Jooris, R., Boone, F., Haesebrouck, F., Van Rooij, D. & Pasmans, F. Road-killed common toads (Bufo bufo) in Flanders (Belgium) reveal low prevalence of ranaviruses and Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis . J. Wild. Dis. 48, 835–839 (2012).

Souza, M. J., Fray, M. J., Colclough, P. & Miller, D. L. Prevalence of infection by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and ranavirus in eastern Hellbenders (Cryptobranchus alleganiensus alleganiensis) in eastern Tennessee. J. Wild. Dis. 48, 560–566 (2012).

Duffus, A. L. J. Chytrid blinders: what other disease risks to amphibians are we missing? EcoHealth 6, 335–339 (2009).

Bosch, J., Martínez-Solano, I. & Garcia-Paris, M. Evidence of a chytrid fungus infection involved in the decline of the common midwife toad (Alytes obstetricans) in protected areas of central Spain. Biol. Conserv. 97, 331–337 (2001).

Bosch, J. & Rincón, P. A. Chytridiomycosis-mediated expansion of Bufo bufo in a montane area of Central Spain: an indirect effect of the disease. Divers. Distrib. 14, 637–643 (2008).

Garner, T. W. J., Walker, S., Bosch, J., Leech, S., Rowcliffe, J. M., Cunningham, A. A. & Fisher, M. C. Life history trade-offs influence mortality associated with the amphibian pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis . Oikos 118, 783–791 (2009).

Baláž, V., Vörös, J., Civiš, P., Vojar, J., Hettyey, A., Sós, E., Dankovics, R., Jehle, R., Christiansen, D. G., Clare, F., Fisher, M. C., Garner, T. W. J. & Bielby, J. Assessing risk and guidance on monitoring of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in Europe through identification of taxonomic selectivity of infection. Conserv. Biol. 28, 213–223 (2014).

Schmeller, D. S., Blooi, M., Martel, A., Garner, T. W. J., Fisher, M. C., Azemar, F., Clare, F. C., Leclerc, C., Jäger, L., Guevara-Nieto, M., Loyau, A. & Pasmans, F. Microscopic aquatic predators strongly affect infection dynamics of a globally emerged pathogen. Curr. Biol. 24, 176–180 (2014).

Medina, D., Garner, T. W. J., Carrascal, L. M. & Bosch, J. Delayed metamorphosis of amphibian larvae facilitates Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis transmission and persistence. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 117, 85–92 (2015).

Gray, M. J., Miller, D. L. & Hoverman, J. T. Ecology and pathology of amphibian ranaviruses. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 87, 243–266 (2009).

van Strien, A. J., Pannekoek, J. & Gibbons, D. W. Indexing European bird population trends using results of national monitoring schemes: a trial of a new method. Bird Study 48, 200–213 (2001).

Stöhr, A. C., López-Bueno, A., Blahak, S., Caeiro, M. F., Rosa, G. M., Alves de Matos, A. P., Martel, A., Alejo, A. & Marschang, R. E. Phylogeny and differentiation of reptilian and amphibian ranaviruses detected in Europe. PLoS ONE 10, e0118633 (2015).

Schock, D. M., Ruthig, G. R., Collins, J. P., Kutz, S. J., Carrière, S., Gau, R. J., Veitch, A. M., Larter, N. C., Tate, D. P., Guthrie, G., Allaire, D. G. & Popko, R. A. Amphibian chytrid fungus and ranaviruses in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 92, 231–240 (2010).

Whitfield, S. M., Geerdes, E., Chacon, I., Ballestero Rodriguez, E., Jimenez, R. R., Donnelly, M. A. & Kerby, J. L. Infection and co-infection by the amphibian chytrid fungus and ranavirus in wild Costa Rican frogs. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 104, 173–178 (2013).

Balseiro, A., Dalton, K. P., del Cerro, A., Márquez, I., Parra, F., Prieto, J. M. & Casais, R. Outbreak of common midwife toad virus in alpine newts (Mesotriton alpestris cyreni) and common midwife toads (Alytes obstetricans) in Northern Spain: A comparative pathological study of an emerging ranavirus. Vet. J. 186, 256–258 (2010).

Greer, A. L., Briggs, C. J. & Collins, J. P. Testing a key assumption of host-pathogen theory: Density and disease transmission. Oikos 117, 1667–1673 (2008).

de Castro, F. & Bolker, B. Mechanisms of disease-induced extinction. Ecol. Lett. 8, 117–126 (2005).

Jancovich, J. K., Davidson, E. W., Morado, J. F., Jacobs, B. L. & Collins, J. P. Isolation of a lethal virus from the endangered tiger salamander Ambystoma tigrinum stebbinsi . Dis. Aquat. Organ. 31, 161–167 (1997).

Brenes, R., Gray, M. J., Waltzek, T. B., Wilkes, R. P. & Miller, D. L. Transmission of Ranavirus between ectothermic vertebrate hosts. PLoS ONE 9, e92476 (2014).

Alves de Matos, A. P., Caeiro, M. F., Papp, T., Matos, B. A., Correia, A. C. & Marschang, R. E. New viruses from Lacerta monticola (Serra da Estrela, Portugal): further evidence for a new group of nucleo-cytoplasmic large deoxyriboviruses (NCLDVs). Microsc. Microanal. 17, 101–108 (2011).

Bandín, I. & Dopazo, C. P. Host range, host specificity and hypothesized host shift events among viruses of lower vertebrates. Vet. Res. 42, 67 (2011).

Baptista, N., Penado, A. & Rosa, G. M. Insights on the Triturus marmoratus predation upon adult newts. Bol. Asoc. Herpetol. Esp. 26, 2–4 (2015).

Oliveira, J. M., Santos, J. M., Teixeira, A., Ferreira, M. T., Pinheiro, P. J., Geraldes, A. & Bochechas, J. Projecto AQUIRIPORT: Programa Nacional de Monitorização de Recursos Piscícolas e de Avaliação da Qualidade Ecológica de Rios. (Direcção-Geral dos Recursos Florestais, Lisboa, 2007).

Bosch, J., Sanchez-Tomé, E., Fernández-Loras, A., Oliver, J. A., Fisher, M. C. & Garner, T. W. J. Successful elimination of a lethal wildlife infectious disease in nature. Biol. Lett. 11, 20150874 (2015).

Arnold, N. & Ovenden, D. A field guide to the reptiles and amphibians of Britain and Europe. (Harper Collins Publishers, 2002).

Daveau, S. La glaciation de la Serra da Estrela. Finisterra 6, 5–40 (1971).

Mora, C., Vieira, G. & Alcoforado, M. J. Daily minimum air temperatures in the Serra da Estrela, Portugal. Finisterra 36, 49–59 (2001).

Nichols, D. K., Lamirande, E. W., Pessier, A. P. & Longcore, J. E. Experimental transmission of cutaneous chytridiomycosis in dendrobatid frogs. J. Wild. Dis. 37, 1–11 (2001).

Retallick, R. W. R., Miera, V., Richards, K. L., Field, K. J. & Collins, J. P. A non-lethal technique for detecting the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis on tadpoles. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 72, 77–85 (2006).

Hyatt, A. D., Boyle, D. G., Olsen, V., Boyle, D. B., Berger, L., Obendorf, D., Dalton, A., Kriger, K., Hero, M., Hines, H., Phillott, R., Campbell, R., Marantelli, G., Gleason, F. & Colling, A. Diagnostic assays and sampling protocols for the detection of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis . Dis. Aquat. Organ. 73, 175–192 (2007).

St-Amour, V. & Lesbarrères, D. Genetic evidence of Ranavirus in toe clips: An alternative to lethal sampling methods. Conserv. Genet. 8, 1247–1250 (2007).

Martin, D. & Hong, H. The use of Bactine in the treatment of open wounds and other lesions in captive anurans. Herpetol. Rev. 22, 21 (1991).

Laurentino, T. G., Pais, M. P. & Rosa, G. M. From a local observation to a European-wide phenomenon: Amphibian deformities at Serra da Estrela Natural Park, Portugal. Basic Appl. Herpetol. 30, doi: 10.11160/bah.1500 (2016).

Speare, R., Berger, L., Skerratt, L. F., Alford, R., Mendez, D., Cashins, S., Kenyon, N., Hauselberger, K. & Rowley, J. Hygiene protocol for handling amphibians in field studies. Available at http://www.jcu.edu.au/school/phtm/PHTM/frogs/field-hygiene.pdf (accessed January 2015) (2004).

Boyle, D. G., Boyle, D. B., Olsen, V., Morgan, J. A. & Hyatt, A. D. Rapid quantitative detection of chytridiomycosis (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) in amphibian samples using real-time Taqman PCR assay. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 60, 141–148 (2004).

Mao, J., Hedrick, R. P. & Chinchar, V. G. Molecular characterization, sequence analysis, and taxonomic position of newly isolated fish iridoviruses. Virology 229, 212–220 (1997).

Löytynoja, A. & Goldman, N. Phylogeny-aware gap placement prevents errors in sequence alignment and evolutionary analysis. Science 320, 1632–1635 (2008).

Waterhouse, A. M., Procter, J. B., Martin, D. M. A., Clamp, M. & Barton, G. J. Jalview Version 2-a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25, 1189–1191 (2009).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Smith, S. A. & Dunn, C. W. Phyutility: a phyloinformatics tool for trees, alignments and molecular data. Bioinformatics 24, 715–716 (2008).

Huelsenbeck, J. P. & Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17, 754–755 (2001).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML Version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. btu033 (2014).

McCullagh, P. & Nelder, J. A. Generalized Linear Models, 2nd edn. (Chapman & Hall, 1989).

van Strien, A. J., Pannekoek, J., Hagemeijer, W. & Verstrael, T. A loglinear Poisson regression method to analyse bird monitoring data. Bird. Census News 13, 33–39 (2004).

Pannekoek, J. & van Strien, A. J. TRIM 3 Manual. TRends and Indices for Monitoring data. Research paper No. 0102. (Statistics Netherlands, 2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank José Conde (CISE) and Ricardo Brandão (CERVAS) for all the support and logistics. Bernardo Duarte (MARE) and Mark Blooi (Ghent University) for helping with hydrochemical analysis. Ana Ferreira, Ana Marques, Andreia Penado, Diogo Veríssimo, Isabela Berbert, Madalena Madeira, Maria Alho, Marta Palmeirim, Marta Sampaio, Miguel Pais, Ninda Baptista and Pedro Patrício for all the help in the field. We also thank Arco van Strien for the tips and advices about the software TRIM. Research permits were provided by the Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas. GMR was holding a doctoral scholarship (SFRH/BD/69194/2010) from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT). TGL was supported by UL/Fundação Amadeu Dias (2011/2012). SJP and TWJG were supported by Natural Environment Research Council grants NE/M00080X/1, NE/M000338/1 & NE/M000591/1. JB was supported by Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness grant CGL2015-70070-R.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M.R. conceived and designed the study. G.M.R., J.S.-P., T.G.L. and J.B. performed sampling. G.M.R., J.S.-P., T.G.L. and R.R. performed skeletochronological analysis. A.M. and F.P. performed post-mortems. G.M.R., A.M., F.P. and S.J.P. carried out molecular screening. S.J.P., A.C.S. and R.E.M. performed sequencing. S.J.P. carried out phylogenetic analyses and advised on interpretation. G.M.R. performed statistical analyses. G.M.R. and T.W.J.G. wrote the manuscript. All co-authors contributed to reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Rosa, G., Sabino-Pinto, J., Laurentino, T. et al. Impact of asynchronous emergence of two lethal pathogens on amphibian assemblages. Sci Rep 7, 43260 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43260

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43260

This article is cited by

-

Drivers of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis infection load, with evidence of infection tolerance in adult male toads (Bufo spinosus)

Oecologia (2023)

-

Host–multiparasite interactions in amphibians: a review

Parasites & Vectors (2021)

-

Three Pathogens Impact Terrestrial Frogs from a High-Elevation Tropical Hotspot

EcoHealth (2021)

-

Single infection with Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis or Ranavirus does not increase probability of co-infection in a montane community of amphibians

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Triple dermocystid-chytrid fungus-ranavirus co-infection in a Lissotriton helveticus

European Journal of Wildlife Research (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.