Abstract

Geographic patterns in leaf stoichiometry reflect plant adaptations to environments. Leaf stoichiometry variations along environmental gradients have been extensively studied among terrestrial plants, but little has been known about intraspecific leaf stoichiometry, especially for wetland plants. Here we analyzed the dataset of leaf N and P of a cosmopolitan wetland species, Phragmites australis, and environmental (geographic, climate and soil) variables from literature and field investigation in natural wetlands distributed in three climatic regions (subtropical, temperate and highland) across China. We found no clear geographic patterns in leaf nutrients of P. australis across China, except for leaf N:P ratio increasing with altitude. Leaf N and N:P decreased with mean annual temperature (MAT), and leaf N and P were closely related to soil pH, C:N ratio and available P. Redundancy analysis showed that climate and soil variables explained 62.1% of total variation in leaf N, P and N:P. Furthermore, leaf N in temperate region and leaf P in subtropical region increased with soil available P, while leaf N:P in subtropical region decreased with soil pH. These patterns in P. australis different from terrestrial plants might imply that changes in climate and soil properties can exert divergent effects on wetland and terrestrial ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), two of the most abundant macroelements in plants, can control plant growth, alter species composition and influence ecosystem functioning1,2. Because of their significance, N and P in plants, especially in leaves, have been frequently studied in biogeochemistry, community ecology and ecosystem ecology1,2,3. For example, N:P ratio were used to infer the nutrient limitation of plant populations and communities4,5. Plant N and P have also been frequently investigated to explore the effects of environmental changes on biogeochemical cycling6,7. Besides, N and P of organisms are effective tools to study the nutrient and energy flows in food webs across multiple trophic levels3,8,9.

Studying variation in N and P of plants along environmental gradients can improve our understanding and prediction of the responses of plant tissue nutrients to environmental changes2,10. Previous interspecific studies have found that leaf N and P varied along geographic gradients, e.g., leaf N and P increased with latitude and altitude11,12,13,14. Several hypotheses, related to climate and soil, were proposed to explain these geographic patterns. First, the Temperature-Dependent Physiology Hypothesis11,15 predicts that tissue P increased more rapidly than N at lower temperature, and tissue N:P ratio increased with increasing temperature and decreasing latitude. The reason is that plants need more P-rich ribosomes than N-rich proteins to sustain growth at lower temperature11. Second, the Growing Season Duration Hypothesis3,16 predicts that plants at sites with shorter growing season (e.g. higher latitude) tend to grow more rapidly to achieve their life history, thus, they always have higher P, and lower N:P ratio. Third, the Environmental Nutrient Supply Hypothesis17,18,19 predicts that plant nutrient contents are strongly correlated with nutrient availability in the soil. The shift from N to P limitation in soils toward lower latitude makes tissue N:P ratio decreased with increasing latitude17,18,19.

However, most of previous studies on geographic variation in leaf N and P mainly focused on terrestrial plants and little on wetland plants. No clear evidence showed that whether there is the same latitudinal gradient in nutrient limitation in wetlands as that in terrestrial lands. Azonal distribution of wetland plants makes them showing weaker relationships with climate than terrestrial plants20. These two aspects might cause the geographic trends in leaf N and P of wetland plants to be different from that of terrestrial plants. To the best of our knowledge, intraspecific variation in leaf N and P of wetland plants were seldom investigated (but see Zhou et al.21). Investigating the geographic variation in leaf N and P within species can help to uncover the mechanism of relationships between plant tissue nutrients and environments21. In addition, it can exclude the confounding effects of taxonomic and phylogenetic structure like those found to influence the geographic patterns in leaf nutrients, and their linkages to climate and soil22,23,24. Although several previous works focused on the variation of plant tissue nutrients within species, most of them were conducted along relatively narrow environmental gradients10,25,26. To more accurately predict the responses of a single plant species to climate change, especially in terms of the leaf stoichiometry, large-scale studies are needed to fully determine the geographical pattern of leaf N and P at intraspecific level.

In this study, we aimed to explore the intraspecific patterns in leaf N and P of wetland species in relation to climate and soil variables in three climatic regions (subtropical, temperate and highland). Considering the differences between wetland and terrestrial ecosystems, we first hypothesized that there are geographic patterns in leaf N, P and N:P ratio of a wetland species, and they are different from what has been previously reported in terrestrial plants. Because wetlands are azonal and they are more influenced by local environmental factors20, we then hypothesized that leaf N, P and N:P ratio of a wetland species are less influenced by climate than by soil. At last, different climatic regions cover different parts of environmental gradients, thus, we hypothesized that leaf N, P and N:P ratio of a wetland species at different climatic regions are affected by different environmental factors.

To test these hypotheses, we used the data set on leaf N and P of the wetland plant Phragmites australis and environmental variables from published studies and our field investigation in natural wetlands across the species range in China. Phragmites australis, a cosmopolitan grass, is dominant in many wetland ecosystems. It distributed widely in different climatic regions from tropical to temperate regions in China as well as in the world27. Owing to both phenotypic plasticity and genetic variability, the variation in morphological and chemical traits of P. australis is considerable27,28,29. These characteristics made P. australis a suitable plant for studying the intraspecific variation in leaf N and P.

Results

Leaf N, P and N:P ratio of P. australis across China

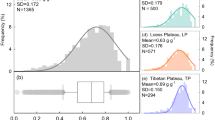

The means (±SD) of leaf N, P and N:P ratio of P. australis were 26.4 ± 8.6 mg g−1, 1.8 ± 0.8 mg g−1 and 16.1 ± 4.6, respectively. Leaf P varied the most, ranging from 0.6 to 4.1 mg g−1, while leaf N:P ratio the least, ranging from 5.4 to 31.2, across the geographic range of P. australis in China (Fig. 1). Leaf N varied from 9.8 to 46.5 mg g−1 (Fig. 1).

One-way ANOVA showed that climatic regions had significant effects on leaf N (F(2,92) = 12.85, p < 0.001) and N:P ratio (F(2,80) = 6.34, p = 0.003), but not on leaf P (F(2,85) = 0.74, p = 0.482). Leaf N in highlands (mean = 33.5, SD = 6.9) was significantly higher than that in subtropical (mean = 24.5, SD = 9.4) and temperate regions (mean = 23.9, SD = 6.5). Leaf N:P ratio in highlands (mean = 18.7, SD = 4.5) was significantly higher than in subtropical (mean = 14.3, SD = 1.9) and temperate regions (mean = 15.8, SD = 4.4).

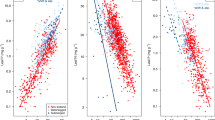

Effects of environmental variables on leaf N, P and N:P ratio of P. australis across China

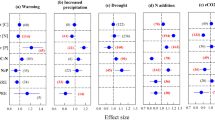

Leaf N:P ratio of P. australis increased significantly with altitude (t = 2.48, p = 0.013), while leaf N and P didn’t show significant trends along latitudinal or altitudinal gradients (p > 0.05; Fig. 2). Leaf N of P. australis decreased with MAT (mean annual temperature; t = −2.59, p = 0.009), soil pH (t = −2.27, p = 0.023) and soil C:N ratio (t = −2.00, p = 0.046), but increased with soil available P (t = 2.79, p = 0.005; Fig. 3). Leaf P was negatively correlated with soil C:N ratio (t = −2.44, p = 0.015) and positively with soil available P (t = 2.26, p = 0.024; Fig. 3). Leaf N:P ratio decreased significantly with MAT(t = −2.69, p = 0.007; Fig. 3). Leaf nutrients are more correlated with soil variables than climate factors based on the number of significant relationships and R2 values (variance explained) (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S1).

Redundancy analysis for the covariation between leaf nutrients and environmental factors showed that 62.1% of total variation in leaf nutrients was explained by climate and soil variables (Fig. 4). Leaf N and P were mainly explained by MAT, soil pH, soil available P and soil C:N ratio, while leaf N:P ratio was related to TWQ (mean temperature of warmest quarter), soil organic C, soil N and soil available N (Fig. 4). Leaf N, P and N:P ratio of P. australis in different climatic regions were explained by different environmental factors (Fig. 4).

Relationships between leaf N, P and N:P ratio and environmental variables in different climatic regions

Leaf N of P. australis in different climatic regions showed different geographic patterns, i.e. it decreased with latitude in temperate region (t = −2.36, p = 0.018) and increased with altitude in subtropical region (t = 2.21, p = 0.027). Leaf P and N:P ratio did not have any clear geographic patterns in all the three climatic regions (Fig. 2).

Leaf N, P and N:P ratio of P. australis in the three climatic regions were predicted by few climate or soil factors (Fig. 3). Leaf N in temperate region (t = 1.99, p = 0.046) and leaf P in subtropical region (t = 2.29, p = 0.022) increased with increasing soil available P. Leaf N:P ratio in subtropical region decreased with soil pH (t = −3.02, p = 0.003).

Discussion

Leaf N and N:P ratio of P. australis were highest in highlands, which may be due to the much lower temperature and higher soil N in this climatic region (Supplementary Fig. S1). Low temperature tended to aid the physiological acclimation of N and P, which was predicted by the Temperature-Dependent Physiology Hypothesis11,15,30. The relatively low leaf P of P. australis in highlands was probably related to P limitation, because the mean of leaf N:P ratio (18.1) of P. australis was above 16 (N:P ratio < 14 indicates N limitation, while N:P ratio > 16 indicates P limitation)4,5, and soil P was low in this region (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Leaf N and P of P. australis found in this study seemed to be higher than that of this species in European wetlands (mean: N ≈ 14.0 mg g−1; P ≈ 1.0 mg g−1), and leaf N:P ratio was similar in these two areas31 (mean ≈ 15.0). The difference in leaf N and P was probably because of the differences in environmental variables (both climate and soil) between wetlands in China and Europe. Meanwhile, P. australis, similar to other aquatic macrophytes (t-tests, p = 0.477), had a higher leaf N than terrestrial plant species (Supplementary Table S2; t-tests, p < 0.001). Compared with other aquatic macrophytes, P. australis had lower leaf P (t-tests, p < 0.001) and higher leaf N:P ratio (t-tests, p < 0.001), which was more similar to terrestrial plants (Supplementary Table S2). Since leaf N:P ratio has frequently been found to be negatively related to relative growth rate of plants1,2, it implies that P. australis had a lower relative growth rate which is similar to terrestrial plants rather than to most of aquatic macrophytes.

Leaf N, P and N:P ratio of terrestrial plants have been extensively investigated11,12,14,23,24,32,33. However, the variation in stoichiometry of wetland plants, especially for intraspecific variation, was unclear. In this study, we investigated the variation in leaf nutrients of a single wetland species across large geographic scales in relation to climate and soil factors. Inconsistent with our expectation, weak geographic patterns in leaf nutrients of P. australis, except for leaf N:P ratio along altitude, were found across the species range in China (Fig. 2). Negative relationship between leaf N and MAT was consistent with what has been largely found among species in terrestrial ecosystems11,12,14,33, which supported the Temperature-Dependent Physiology Hypothesis11,15. Moreover, strong relationships between leaf N, P and soil properties (soil pH, soil C:N ratio and soil available P) were consistent with the Environmental Nutrient Supply Hypothesis17,18,19. These facts emphasized the importance of temperature and soil factors, most of which are correlated with each other (Supplementary Table S3), in determining leaf nutrients of P. australis. The influences of soil and climate on leaf nutrients had shown weak geographic patterns in leaf stoichiometry of P. australis, which might be related to the following two main reasons. First, as azonal vegetation, wetland plants were relatively weakly influenced by climate factors compared with local abiotic or biotic factors20,27. It explained why there were weak linkages between leaf P and MAT or latitude (Figs 2 and 3). Second, although leaf N and P were strongly correlated with soil properties, such as soil pH, soil C:N ratio and soil available P, there was no clear geographic gradients in nutrient limitation in wetlands.

The weak geographic patterns in leaf nutrients of P. australis are different from what has been previously found in terrestrial plants across China12,33 and the globe11,14, in which leaf N and P increase with latitude and altitude. The comparison of other wetland plants to terrestrial plants also supported this, although there are some differences in the variation in leaf nutrients among different species (Supplementary Table S4). It may suggest that implicit mechanism of variation in stoichiometry of wetland plants might differ from terrestrial plants. Since wetland plants were relatively little investigated, there are great needs to explore geographic variation in leaf nutrients of wetland plants34. Moreover, our study found the greater effects of soil on stoichiometry of P. australis than climate, which showed some lights on the causes of intraspecific variation in leaf stoichiometry of widely distributed species21,35. Furthermore, P. australis is a dominant species in many wetland ecosystems27, and leaf chemistry is strongly linked to nutrient cycling2, therefore, this study will help us to understand the effects of environment change on wetland ecosystem functioning.

There was a negative latitudinal trend in leaf N in temperate region and positive altitudinal pattern in leaf N in subtropical region. Leaf N of P. australis in temperate region and leaf P in subtropical region increased with increasing soil available P. However, leaf N:P ratio in subtropical region decreased with soil pH. In other words, relationships between leaf N, P and N:P ratio and environmental variables differed among climatic regions. This was probably not due to the limited ranges of leaf N, P and N:P ratio in some climatic regions in this study. Because sampling sites were almost evenly distributed across each region (Supplementary Table S5), and there were no obvious differences in the ranges of leaf N, P and N:P ratio among the three climatic regions (Fig. 1). In different climatic regions, multiple environmental variables, including soil nutrients and climate factors, are likely to shape leaf stoichiometry variation. This is consistent with the study of Kang et al.35, which showed significant geographic patterns of leaf N and P in temperate region instead of in Mediterranean and boreal regions. Therefore, we conclude that climatic regions modulated the responses of leaf N, P and N:P ratio to environmental gradients.

Plant leaf N, P and N:P ratio varied among climatic regions, functional groups and ecosystems12,13. Previous studies compared the variation in leaf N, P and N:P ratio along environmental gradients among taxa, functional groups, life forms and ecosystems11,12,14,24,34. In this study, we investigated the geographic variation in leaf N, P and N:P ratio in different climatic regions, and found that leaf nutrients in different climatic regions responded differently to environmental variables. Different climatic regions, similar to different sampling zone within species ranges, resulted in different patterns of variation in leaf nutrient along environmental gradients25. This provides insight into the mechanism of variation in plant leaf nutrients. In addition, our results suggest that it is necessary to consider the effects of climatic regions when studying the relationships between leaf nutrients and the environment, which might help us better understand the responses of plant nutrients to environmental changes.

In this study, we investigated the intraspecific variation in leaf N and P along wide environmental gradients with the cosmopolitan wetland plant P. australis. We found no clear geographic patterns in leaf nutrients of P. australis, except for leaf N:P ratio along altitude, across the species range in China. This differs from what has been previously reported in terrestrial plants, for which leaf N and P increase with latitude and altitude. Moreover, leaf N and N:P ratio decreased with increasing MAT, while leaf N and P were strongly correlated with soil pH, soil C:N ratio and soil available P. This did not explain the geographic trends in leaf nutrients of P. australis, but suggests that climate and soil variables are able to shape the intraspecific patterns of leaf N and P stoichiometry. Furthermore, we found that the relationships between leaf N, P and N:P ratio and environmental variables differed among climatic regions, indicating that leaf nutrients in different climatic regions responded differently to environmental variables. Our findings have important implications for understanding the determinants of variation in plant tissue nutrients and predicting plant responses to environmental changes. Since we investigated the influences of climate and soil on only one widespread wetland plant, more studies on other wetlands species are needed to gain insight into the effects of climate change and N deposition on wetland ecosystem functioning.

Materials and Methods

Data set of leaf N and P in P. australis

Data for leaf N and P of P. australis and climatic and soil variables across China were obtained from published literature and our field investigation. We collected the data from peer-reviewed papers, dissertations and books both in Chinese and English, and removed the duplicates among them. To minimize errors caused by spatial and temporal variability, we collected data based on the following criteria: 1) natural population of P. australis, excluding those from greenhouse and field experiments; 2) wetland habitats, excluding terrestrial habitats; 3) data were collected in growing seasons (July to September); 4) data were obtained only for sites without obvious disturbances. For some studies having several measures from July to September, the averages were calculated. Data from our field investigation also met these criteria. Mature leaves of P. australis were collected from 16 sites in natural wetlands across China during the growing seasons. The detailed sampling methods for our field investigation were described in Hu et al.29. The final data set included 58 sampling sites from 29 publications and our field investigation (Supplementary Table S5; Data S1). These sampling sites spanned latitudes from 22.1°N to 47.6°N and longitudes from 83.5°E to 133.5°E, covering most of the geographic ranges of P. australis in China (Supplementary Table S5). They covered large climatic gradients with MAT −0.4 to 22.7 °C and MAP 40 to 2223 mm.

Sampling sites were distributed in three climatic regions—subtropical, temperate and highland; highlands represented the climate of the Tibetan Plateau36. The three climatic regions differed in both climate and soil variables (Supplementary Fig. S1). Given the large variability in traits of P. australis at small scales29, leaf N and P were collected and measured at plot level, i.e. 1–4 plots within each sampling site. We identified the plot trait data according to the information of published studies. For some studies which were conducted at the same sites but by different authors and in different years, we treated data from these studies as independent plots. In total, we had 100 plots, i.e. 100 records for leaf N, P and N:P ratio.

Leaf N and P

We collected leaf N and P of P. australis from published papers based on the same criteria as mentioned above. In our field investigation, leaf N was determined with an elemental analyzer (vario PYRO cube; Elemental, Germany), while leaf P was determined using ascorbic acid colorimetric method after H2SO4 digestion as described by Bao (2005)37. Leaf N and P were all expressed on a mass basis (mg g−1). Leaf N:P ratio was also collected from publications or calculated by the ratio of leaf N to P.

Environmental variables

Latitude, longitude and altitude of sampling sites were recorded in our investigation or collected from publications. MAT and MAP were obtained directly from literature, and if they were not accessible in literature, we obtained them from the WorldClim database (http://www.worldclim.org/) according to geographical coordinate of each site38. Notably, for most of sampling sites in highlands (the Tibetan Plateau), MAT rather than latitude and longitude were provided, in which case MAT was the only climate variable (Supplementary Table S5). Temperature seasonality (TS), precipitation seasonality (PS), mean diurnal range (DRT, °C), mean temperature of warmest quarter (TWQ, °C), and mean precipitation of warmest quarter (PWQ, mm) for each site were also obtained from the WorldClim. We collected soil variables, including soil pH, soil electrical conductivity (soil EC, ms cm−1), soil N (mg g−1), soil P (mg g−1), soil C:N ratio, soil organic C (mg g−1), soil available N (mg kg−1) and soil available P (mg kg−1), of each plot from the literature. In our field investigation, we determined these eight soil variables using the methods described in Hu et al.29.

Statistical analyses

We first calculated the mean, standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) of leaf N and P in P. australis overall and in three climatic regions. Before the following statistical analyses, MAP and PWQ were square root-transformed, while leaf P, altitude, soil N, soil P, soil C:N ratio, soil EC, soil organic C, soil available N, soil available P, DRT, PS were log10-transformed. Leaf N, leaf N:P ratio, latitude, MAT, TS, TWQ and soil pH were not transformed as they showed approximately normal distributions.

We carried out one-way ANOVAs and post hoc tests (Tukey’s HSD) to address the differences in leaf N, P and N:P ratio among the three climatic regions. Because our data has a multilevel structure (i.e. variance at the plot level is nested within that at the site level), we used multilevel models to address the effects of environmental variables on leaf N, P and N:P ratio. Each climate or soil variable was used as a predictor and fixed factor, and site as a random factor. We conducted the multilevel models with lmer function in lme4 package of R, and parameter estimates were based on restricted maximum likelihood (REML)39. Finally, to explore the effects of soil and climate on the matrix of leaf N, P and N:P ratio, we performed redundancy analysis with rda function in R package vegan40. All analyses were performed in R 3.2.3 (R Core Team 2015)41.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hu, Y.-K. et al. Intraspecific N and P stoichiometry of Phragmites australis: geographic patterns and variation among climatic regions. Sci. Rep. 7, 43018; doi: 10.1038/srep43018 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Güsewell, S. N: P ratios in terrestrial plants: variation and functional significance. New Phytol. 164, 243–266 (2004).

Sardans, J., Rivas-Ubach, A. & Peñuelas, J. The elemental stoichiometry of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems and its relationships with organismic lifestyle and ecosystem structure and function: a review and perspectives. Biogeochemistry 111, 1–39 (2012).

Elser, J. J. et al. Biological stoichiometry from genes to ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 3, 540–550 (2000).

Koerselman, W. & Meuleman, A. F. M. The vegetation N:P ratio: a new tool to detect the nature of nutrient limitation. J. Appl. Ecol. 33, 1441–1450 (1996).

Güsewell, S., Koerselman, W. & Verhoeven, J. T. A. Biomass N: P ratios as indicators of nutrient limitation for plant populations in wetlands. Ecol. Appl. 13, 372–384 (2003).

Elser, J. J. et al. Shifts in lake N:P stoichiometry and nutrient limitation driven by atmospheric nitrogen deposition. Science 326, 835–837 (2009).

Litchman, E. et al. Global biogeochemical impacts of phytoplankton: a trait-based perspective. J. Ecol., 103, 1384–1396 (2015).

Elser, J. J. et al. Nutritional constraints in terrestrial and freshwater food webs. Nature 408, 578–580 (2000).

Scharler, U. M. et al. Variable nutrient stoichiometry (carbon:nitrogen:phosphorus) across trophic levels determines community and ecosystem properties in an oligotrophic mangrove system. Oecologia 179, 863–876 (2015).

Gotelli, N. J. et al. Geographic variation in nutrient availability, stoichiometry, and metal concentrations of plants and pore-water in ombrotrophic bogs in New England, USA. Wetlands 28, 827–840 (2008).

Reich, P. B. & Oleksyn, J. Global patterns of plant leaf N and P in relation to temperature and latitude. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 101, 11001–11006 (2004).

Han, W. X., Fang, J. Y., Guo, D. L. & Zhang, Y. Leaf nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry across 753 terrestrial plant species in China. New Phytol. 168, 377–385 (2005).

He, J. S. et al. Leaf nitrogen:phosphorus stoichiometry across Chinese grassland biomes. Oecologia 155, 301–310 (2008).

Borer, E. T. et al. Global biogeography of autotroph chemistry: is insolation a driving force? Oikos 122, 1121–1130 (2013).

Woods, H. A. et al. Temperature and the chemical composition of poikilothermic organisms. Funct. Ecol. 17, 237–245 (2003).

Kerkhoff, A. J., Enquist, B. J., Elser, J. J. & Fagan, W. F. Plant allometry, stoichiometry and the temperature-dependence of primary productivity. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 14, 585–598 (2005).

Walker, T. W. & Syers, J. K. Fate of phosphorus during pedogenesis. Geoderma 15, 1–19 (1976).

Vitousek, P. M. & Farrington, H. Nutrient limitation and soil development: Experimental test of a biogeochemical theory. Biogeochemistry 37, 63–75 (1997).

Chadwick, O. A., Derry, L. A., Vitousek, P. M., Huebert, B. J. & Hedin, L. O. Changing sources of nutrients during four million years of ecosystem development. Nature 397, 491–497 (1999).

Walter, H. Vegetation of the Earth and Ecological Systems of the Geo-biosphere, 3rd edn. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1985).

Zhou, W., Wang, Z., Xing, W. & Liu, G. Plasticity in latitudinal patterns of leaf N and P of Oryza rufipogonin China. Plant Biol. 16, 917–923 (2014).

Stock, W. D. & Verboom, G. A. Phylogenetic ecology of foliar N and P concentrations and N:P ratios across mediterranean-type ecosystems. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 21, 1147–1156 (2012).

Zhang, S. B., Zhang, J. L., Slik, J. W. F. & Cao, K. F. Leaf element concentrations of terrestrial plants across China are influenced by taxonomy and the environment. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 21, 809–818 (2012).

Yang, X. J., Huang, Z. Y., Zhang, K. L. & Cornelissen, J. H. C. C:N:P stoichiometry of Artemisia species and close relatives across northern China: unravelling effects of climate, soil and taxonomy. J. Ecol. 103, 1020–1031 (2015).

Albert, C. H. et al. Intraspecific functional variability: extent, structure and sources of variation. J. Ecol. 98, 604–613 (2010).

Li, L. P. et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry of common reed (Phragmites australis) and its relationship to nutrient availability in northern China. Aquat. Bot. 112, 84–90 (2014).

Editorial Committee of Wetland Vegetation in China. Wetland Vegetation in China. (Beijing: Science Press, 1999).

Mal, T. K. & Narine, L. The biology of Canadian weeds. 129. Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. Can. J. Plant Sci. 84, 365–396 (2004).

Hu, Y. K. et al. Novel evidence for within-species leaf economics spectrum at multiple spatial scales. Front. Plant Sci. 6: 901; 10.3389/fpls.2015.00901 (2015).

Wang, Z., Xia, C. X., Yu, D. & Wu, Z. G. Low-temperature induced leaf elements accumulation in aquatic macrophytes across Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Eng. 75, 1–8 (2015).

Güsewell, S. & Koerselman, W. Variation in nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations of wetland plants. Persp. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 5, 37–61 (2002).

Oleksyn, J., Reich, P. B., Zytkowiak, R., Karolewski, P. & Tjoelker, M. G. Nutrient conservation increases with latitude of origin in European Pinus sylvestris populations. Oecologia 136, 220–135 (2003).

Han, W. X., Fang, J. Y., Reich, P. B., Ian Woodward, F. & Wang, Z. H. Biogeography and variability of eleven mineral elements in plant leaves across gradients of climate, soil and plant functional type in China. Ecol. Lett. 14, 788–796 (2011).

Xia, C. X., Yu, D., Wang, Z. & Xie, D. Stoichiometry patterns of leaf carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous in aquatic macrophytes in eastern China. Ecol. Eng. 70, 406–413 (2014).

Kang, H. Z. et al. Variation in leaf nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry in Picea abies across Europe: An analysis based on local observations. Forest Ecol. Manage. 261, 195–202 (2011).

Editorial Board of Physical Geography in China, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Physical Geography in China: Climatology. (Beijing: Science Press, 1985).

Bao, S. D. Soil Agricultural Chemistry Analysis. (Beijing: China Agriculture Press, 2005).

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G. & Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978 (2005).

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Eigen and S4 Classes. R package version 1, 1–7 (2014).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2, 3–3 (2016).

R. Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Can Jiang and Hong-Ke Xu for their help in the sample analysis, Wei-Qin Zhu and Dan Jiang for their assistance in the laboratory. This work was supported by the NSFC (Grants: 31261120580; 31400346; 41401556) and the Innovative R&D grant (201203) from Hangzhou Normal University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D. designed the experiment, Y.K.H., Y.L.Z., X.P., S.L.T. T.X., L.Y.C., and W.X. executed the experiment. Y.K.H., Y.L.Z., X.P., G.F.L. and Y.B.S. contributed to analyzing the data, and making the figures. Y.K.H., Y.L.Z., G.F.L., X.P., X.J.Y., W.B.L., W.H.D., S.L.T., T.X., L.Y.C., W.X., Y.B.S. and M.D. contributed to writing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, YK., Zhang, YL., Liu, GF. et al. Intraspecific N and P stoichiometry of Phragmites australis: geographic patterns and variation among climatic regions. Sci Rep 7, 43018 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43018

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43018

This article is cited by

-

Inter- and intra-specific phenotypic variation of ecological stoichiometric traits in a mixed-oak secondary forest in China

Journal of Forestry Research (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

, subtropical;

, subtropical;