Abstract

Very little information exists for long-term changes in genetic variation in natural populations. Here we take the unique opportunity to compare a set of data for SNPs in 15 metabolic genes from eastern US collections of Drosophila melanogaster that span a large latitudinal range and represent two collections separated by 12 to 13 years. We also expand this to a 22-year interval for the Adh gene and approximately 30 years for the G6pd and Pgd genes. During these intervals, five genes showed a statistically significant change in average SNP allele frequency corrected for latitude. While much remains unchanged, we see five genes where latitudinal clines have been lost or gained and two where the slope significantly changes. The long-term frequency shift towards a southern favored Adh S allele reported in Australia populations is not observed in the eastern US over a period of 21 years. There is no general pattern of southern-favored or northern-favored alleles increasing in frequency across the genes. This observation points to the fluid nature of some allelic variation over this time period and the action of selective responses or migration that may be more regional than uniformly imposed across the cline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of geographic variation is an important approach in the inference of adaptation in evolutionary genetics, and work in Drosophila melanogaster has played a central role in these investigations over many decades. This special attention is motivated by the complex biogeographic history of this species that involves the interrelationships between migration and local adaptation during a global colonization process, across different time scales. In that effort, many geographic clines in Drosophila melanogaster have been reported and these encompass a wide range of phenotypic and genetic variation that includes physiological, life-history, and morphological traits, chromosomal inversions, and molecular polymorphisms1,2,3,4. A vast majority of this work has investigated populations on the east coast of Australia5 and the eastern US6,7,8.

With respect to the study of molecular polymorphism, the discovery of allozyme clines was first systematically explored by John Oakeshott and colleagues9,10,11,12,13 in a series of papers on Australian, North American, and European collections in the early 1980s. These studies found a number of parallel independent examples of clines in allozyme polymorphisms in the northern and southern hemispheres. These early studies supported the theme of an underlying commonality of clinal selection regimes in both the Australian and North American populations, and these have formed the working hypothesis and context of many studies that suggest these latitudinal clines represent evidence of natural selection acting after colonization and population spread7,14,15,16,17.

Out of these studies emerges the question as to how stable is the observed geographic variation over both short and long time scales? On the short-time scale, there is evidence that some variation can change seasonally18,19,20,21. On the long-time scale, understanding the stability of clines and geographic variation is particularly relevant because the potential selection that maintains polymorphism can be globally or locally changing, and processes such as admixture can always confound interpretation. There is an emerging observation that these D. melanogaster populations and the associated clines in North America and Australia are the result of admixtures of European temperate populations and their ancestral tropical African populations through independent invasive colonizations22,23,24,25. Therefore, a major challenge is to identify which clinal polymorphisms are maintained by ongoing selection and which are the result of admixture and possibly transient neutral variation.

One approach that can help to answer this question is to compare the stability of clines over long time periods, such as over a decade. There is little data on the stability of clines or the local stability of allele frequencies in D. melanogaster. Using the reported data from Oakeshott collections in Australia around 1980, Umina and colleagues26 examined the state of several clines reported from collections from 2000–2002 across the same latitudinal range, spanning a period of about two and half decades. They included clines for Adh and Gpdh and the inversion polymorphisms for In(2L)t and In(3R)Payne. They found notable change for Adh and In(3R)P with the tropically-favored allele increasing over time. Cogni and colleague19 looked at the clinal SNP polymorphisms for the diapause-associated cpo gene27 and found these clines were relatively unchanged compared to the latitudinal clines reported 13 years earlier. In this report, we have the unique opportunity to revisit a number of clines of molecular polymorphisms in some metabolic genes reported in previous studies of Drosophila melanogaster along the east coast of the US. These data are from collections made in 1997 and reported in Sezgin et al.8 and collections from the 2009–2010 used in the analyses by Lavington et al.28. Our main goal is to describe patterns of changes over a 13-years interval in clines in 15 metabolic genes.

Results

Patterns of clinal change over a 13-years period vary among genes

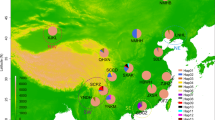

We compared clines in collections along a broad latitudinal gradient in the Eastern US made in 1997 and 2009/2010. We have ten collections made in 1997 that were reported in Sezgin et al.8 and Verrelli and Eanes29, and 18 collections made in 2009/2010 that were reported in Lavington et al.28(Supplemental Table 1). To provide further context we also include SNP frequency estimates for three European populations that extend farther into temperate latitudes (see methods). These studies addressed cline variation in genes involved in central metabolism. We looked for clinal patterns of 21 SNPs distributed in 15 metabolic genes for which we have data for both time points (1997 and 2009–2010). We used a linear model (see methods) that tested the effect of sampling period and latitude on SNP frequency. Specifically, we tested for the presence of a cline (significant regression with latitude) in each sampling period and on all collections combined (Table 1). We also tested for a difference in allele frequency between the two sampling periods and for a difference in the slope of the regression with latitude between the two collection periods (Table 1). Power analyses (see methods) showed that we have good power to detect overall SNP frequency changes between samples, reduced power to detect changes in slope between years, and for the detection of significant clines for each individual SNP the 1997 samples have about half the power of the 2009/2010 samples (Supplemental Fig. 1). The fact that we found many significant clines in the 1997 samples, even with reduced power, indicates that clines in metabolic genes are pervasive. Genes that lie inside the cosmopolitan inversions are indicated in Table 1. Of the 21 SNPs, six were significantly clinal in both sampling time points and eight were not clinal in either year. For seven SNPs a significant cline was observed in only one year, and in five of these cases the clines observed in 1997 were lost in 2009/2010, despite the higher power to detect clines in the 2009/2010 collections (Supplemental Fig. 1). Allele frequencies did not show a statistically significant change for 15 out of 21 SNPs. For six SNPs (in five genes) there was a significant change in average SNP allele frequency corrected for latitude, in three of these five genes the southern associated allele increased in frequency. The overall results for all 15 genes are listed in Table 1. We discuss significant cases below.

Southern trehalase (Treh) allele increased in frequency in northern populations

In the 1997 collections, Sezgin et al.8 reported a cline in the Treh122C. which is an amino acid (V41A) polymorphism. Twelve years later we observe a clear but non-significant shift (t26 = 1.352, P < 0.0941) in the cline that reflects an overall 10% increase in latitude-adjusted frequency of the southern associated Treh122C allele (t26 = 3.45, P < 0.0021). This shift appears driven by an increase of about 15% of the southern allele in northern populations over this period (Fig. 1). This gene lies near the distal breakpoint of inversion In(2R)NS, but this inversion is extremely rare in northern latitudes.

Significant clines in phosphoglucomutase (Pgm) were lost

In the 1997 collections, we reported latitudinal clines in a number of SNPs29. We reexamine four here: one synonymous and three replacement SNPs. In 1997, Pgm200C (syn), Pgm226C(V52A), and Pgm2055G(V484L) had significant clines. Pgm1998T (T465S) did not. In 2009/2010, there are significant changes in these SNPs. Although there are larger sample sizes, none show significant clines (Fig. 2A–D) and Pgm200C and Pgm2055C each show an overall but non-significant (t26 = 1.683, P < 0.0522; t26 = .848, P < 0.202) increase in the latitude-adjusted frequencies of northern-associated alleles into the southern populations. Both alleles show overall significant increases in frequency (t26 = 2.37, P < 0.0261; t26 = 4.88, P < 0.0001). The Pgm200C and Pgm2055G alleles are in linkage disequilibrium with each other29, so their shift is corroborated here. Pgm is inside the inversion In(3L)P, however shifts in the inversion frequency cannot explain the increase in frequency of Pgm200C and Pgm2055G since they have the opposite association inside the inversion.

Significant cline in phosphoglucose isomerase (Pgi) was gained

The amino acid polymorphism in Pgi985A (V329I) possessed no significant cline in 1997, but there is now a significant cline in the 2009/2010 sample (Fig. 3; t = 1.715, p < 0.0491). Pgi985A is defined as a southern favored allele since its frequency is lower in Europe than in the North American populations. Notably, its frequency has increased by 4% overall (t = 2.32, p < 0.0291) and by about 10% in northern populations. It is well outside the In(2R)NS inversion, which is extremely rare in northern latitudes.

Significant cline in glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh1) was lost

Two SNPs in Gapdh1 were screened in 1997 and there was a significant cline in the Gapdh1825C allele. There is also a significant shift in the clines between time intervals (t = 1.924, p < 0.0327). We fail to see this cline in 2009/2010 (Fig. 4). Gapdh1 is well outside the In(2R)NS inversion, which is extremely rare in northern latitudes. This was interpreted as a slight, albeit significant, shift towards the more southern based allele.

Northern phosphoglucokinase (Pgk) allele increased in frequency

Two SNPs in Pgk were screened in 1997 and there was a significant shift in the Pgk639T allele (Fig. 5). This was interpreted as a slight, albeit significant, shift towards the more northern based allele.

Southern glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6pd) allele increased in frequency

We are able to examine allozyme clines for G6pd-F reported in Oakeshott et al.12. This is SNP 1145 in Lavington et al.28 and the amino acid polymorphism P382L30. Oakeshott et al.12 also includes a set of data for three localities collected in the 1970s by Berger31. The data are sampled largely in 1979/1983 and permit a look at potential changes over 29–31 years. In 1983, there was a significant partial regression, but the linear regression in our analysis in 2009/2010 is not significant. In 1979/1983, the frequency of the F allele was nearly 100% in Europe and fixed in many samples, although our three collections for Sweden, England, and Austria show a very low frequency from recent collections. G6pd is X-linked and not associated with any inversion.

There is a dramatic drop in the overall frequency in the GpdhFallele over this three-decade interval (t = 4.23, p < 0.0001; Fig. 6). Earlier collections showed many northern samples where the F allele is found in the ranges of 10 to 50%; these have disappeared in 2009/2010. All change is in the direction of increasing frequency of the southern associated allele.

Southern phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (Pgd) allele increased in frequency

The cline in the PgdF allele (Gln/Lys polymorphism) reported by Oakeshott12 is present decades later (Fig. 7). Both temporal samples show highly significant latitudinal clines (Table 1). There is a clear paucity of samples with PgdF >0.80 in recent collections (perhaps consistent with the influx of southern favored alleles). There is an increase in the frequency of the southern favored allele in northern latitudes.

No changes in alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh) cline in North America over 21 to 27 years

One of the best studied clines in D. melanogaster is the ADH allozyme polymorphism that represents a Thr/Lys amino acid change. We can reexamine the AdhS cline in the eastern US using data collected from 1983 to 1988 by Berry and Kreitman32. Using our Adh data (2009/2010) this spans an interval of 21 to 27 years. There is no significant AdhS frequency difference over this interval (t = 1.17, p < 0.2476) and there is no significant difference in the slopes (Fig. 8A). While the difference in mean change in AdhS allele in North America is not significantly different from zero, nonetheless, it is significantly different from a 10% change observed in the Australian samples. Our power analyses indicates that we have 100% power to detect a 10% change in frequency between 1993 and 2009/2010, and even the detection of a 5% change in frequency has a 93% power (Supplemental information). We can also place our US clines in the context of the Australian clines26 (Fig. 8B). We see the slopes are significantly different (t = 1.761, p < 0.045), but more importantly there is a highly significant displacement in latitude-adjusted mean AdhS frequency (t = 8.97, p < 0.0001).

(A) Eastern US collections in 1979/1980 (open circles), 1997 (grey circles) and 2009/2010 (black circles). (B) Plot of Australian samples from Umina (Umina et al.26) samples in 1979/1980 (open circles) and 2002/2004 (grey circles) against the pooled collection for eastern US all years (black circles).

Discussion

In this report, we first examined 15 genes from 10 US samples that were collected in 1997 by Brian Verrelli and the data reported by Sezgin and colleagues8, and compared these results to a new collection of 18 samples made in 2009–2010 across the same latitudinal range28. In the latter collection, we also sampled the same amino acid polymorphisms in G6pd and Pgd that were examined in North American collections made in the early 1980s12. Finally, we were able to screen and contrast the AdhS allele frequencies in the 2009/2010 to collections made not only in 1997, but also the late 1980s by Berry and Kreitman32 and compare these clines to those reported for the latitudinal ranges studied in Australia. If we assume 10 generations per year in the southern US and six generations in the northern US, our 1997 to 2009/2010 interval spans 75 to 120 generations of potential change.

When we combine the overall data from both US collections, there are clines observed in 11 of 15 genes. This is consistent with the large number of clines reported in D. melanogaster in North America and Australia. Of the 20 SNPs in 15 genes, we see seven cases where a cline was reported in only one sample, but not both samples. In two cases (Pgi, Gapdh1) there is a statistically significant shift in cline slope. While most of the genes show little significant change over the 12 to 13-year time interval here, this implies that even over these relatively short time scales some geographic variation can be fluid.

The different SNPs are likely responding to different processes. While some clines are likely kept by spatial differences in selection19,20,33, some neutral polymorphism may be clinal by the result of admixture of African and European populations24,25. Some clines may first appear as the result of admixture, but spatial differences in selection may maintain them, such as in the case of European adapted alleles being selected against on the populations closer to the tropics. The problems associated with isolation-by-distance in the generation of spatial patterning has been well emphasized34,35. Long term data on the stability of clines as reported here can in principle help to discern among these different hypotheses. For example, if clines are the result of admixture, gene flow will reduce the differences among populations over time and the clines will be lost. Changes in clines for neutral SNPs should be relatively slow over this number of generations, but other measures of admixture, such as linkage disequilibrium, may be predicted to change much more rapidly over these time scales. Although the time of colonization of D. melanogaster is believed to be about 150 years in North America36, the colonization of the tropical New World may be older and the assumption of single point colonization is unknown; furthermore, the precise origins of admixture populations are also not known.

The steep Pgm clines reported in 1997 for SNPs Pgm129C and Pgm2005C are absent in 2009/2010. In both cases, there is a significant increase in the temperate-favored northern allele in southern parts of the cline. Both SNP alleles are in linkage disequilibrium so we expect correlated changes. The reported clines in the Treh amino acid polymorphism and Gapdh1 seen in 1997 appear absent in the 2009/2010 collection and a cline for Pgi, not seen in 1997, is now observed. Both of these latter cases involve increases in the southern-based allele in northern latitudes. We should also emphasize that both Gapdh1 and Pgi are on the 2R arm which carries the In(2R)NS inversion. This inversion is very rare in all eastern US populations6,8,37, including our 1997 populations and is an unlikely cause of change in these genes. The genes that lie inside the cosmopolitan inversions are listed in Table 1.

Both the G6pdF and PgdF alleles were examined in collections from the early 1980s12. These collections permit temporal comparisons of about three decades or perhaps 200 to 300 generations. G6pd shows a notable change in overall frequency with the F allele polymorphism appearing to disappear from northern populations. While there is no significant cline, the global pattern clearly shows the F allele to be temperate-favored (it was nearly fixed in European populations in 1979/1980), while the ancestral S allele is the most common in tropical regions. This is a possible case of invasion of the tropically-favored allele over this three-decade span, or simply the selective removal of the temperate allele. This appears to have also happened in Europe where earlier estimates found it effectively fixed12.

The PgdF allele shows the same cline after 30 years, with a slight, but not significant, shift in overall frequency towards the southern-favored allele. There is again a very notable drop in the frequency of the temperate favored F allele above 35 degrees N latitude. There were many populations with frequencies >80% in the earlier interval, but in 2009/2010 there were none. The European populations are nearly fixed for the F allele12 and this allele has been shown in a genome scan of Netherland samples of the X chromosome to be associated with an apparent selective sweep in this region. This sweep is centered on the Pgd locus38, and may be the cause because of direct selection or be hitchhiking on other genes in the small region of 60.5 kb, and estimated to hold seven genes.

Several interesting features emerge from the comparison of the AdhS allele clines. First, the US samples do not show the same latitude-controlled AdhS allele frequency shift reported by Umina and colleagues26. The S allele frequency is not significantly different among the three-time collection points on the east coast of the US. The data of Berry and Kreitman32, collected 21–22 years earlier than our 2009/2010 collection, is comparable to the Australian study that spanned 23–25 years. The eastern US latitudinal range is smaller, spanning 20 degrees of latitude compared to nearly 30 degrees for the Australian collection, and extends farther into temperate latitudes, but it is doubtful that this causes the lack of a shift in US populations. Second, what is particularly interesting is the displacement of the Australian and eastern US latitudinal clines by 30% at the higher latitudes. This might suggest that temperatures across the US range are higher; however, mean annual temperatures in the higher latitudes are effectively identical between Australian and the eastern US localities at the same latitude. This disparity in Australian and US latitudinal clines should dispel the role of temperature as a sole environmental parameter driving selection of the Adh amino acid polymorphism via simple temperature dependent catalytic function. Umina et al.26 could not identify a single climatic variable that could explain the shift in the cline, suggesting that a combination of climatic factors, possibly including temperature was responsible. Given the large number of studies finding evidence for phenotypic differences for this polymorphism, it is unlikely that natural selection is not a factor in maintaining this polymorphism in Adh. However, as emphasized by Bradshaw and Holzapfel39, latitude is not just reflecting average temperature, but is a proxy for numerous other environmental parameters that likely differ across these continents at these latitudes.

There is interest in studies of long-term changes in using the genetic composition of Drosophila populations, particularly as they serve as proxies for climate-driven change. There are cases where collection data exists from earlier decades40,41,42. Most of this work has focused on chromosomal inversions for which there exists not only data on older collections40, but also known associations with colonization events, such as Drosophila subobscura in the New World43. There is also a growing appreciation of the extent of even short-term seasonally driven shifts in inversion frequencies44,45, something46 recorded in Drosophila pseudoobscura some decades earlier. In D. melanogaster the In(3R)Payne cline in Australian east coast has shifted in position (latitudinal intercept) in 20 years, presumably due to climate changes26,47, but in North America the same inversion has remained invariant across ∼40 years, without any changes in clinal slope or intercept48. Interestingly, the cline in In(2L)t has shifted upwards in latitude, and the cline in In(3L)P has shifted downwards and become more shallow in North America, while clines on both these inversions have remained temporally stable in Australia48. The data here are individually of interest, but still insufficient to reach any general conclusions about increases in northern or southern alleles as a response to climate change or shifts in admixture over this time interval. Future studies looking at genome wide patterns of clinal variation at different time intervals are needed.

The implications of this study of a sample of central metabolic genes suggest that clines and geographic variation can be fluid over decadal scales. Some of these differences may simply reflect variation consistent with repeated geographic samples, and others appear as statistically significant shifts in allele frequency. This is also strongly suggested from seasonal data that implies strong local selection on some genes18,19,20. In both latitudinal samples the tendency is for midseason samples to be collected in north and late season collections made in the south, although there was no significant effect of collection date on the clines reported in Lavington et al.28. We do not know if the observed shifts reflect long-term directional changes or rather recurrent fluctuations in allele frequencies under natural selection or shifts in the genome proportions of European and African ancestry. Given the local structure where populations are likely reseeded from local refugia and subsequently subjected to high gene flow, one might expect regional shifts rather than systematic responses at large across the entire cline. There are long-term average global changes consistent with responses to climatic change, but much year to year change is local or regional. The data here are far too limited to expand questions to larger contexts, such as the functionally connected pathway responses as initiated in Lavington et al.28. The clear question is why are some gene frequencies relatively stable while others are shifting? For example, Treh, G6pd, Pgi, and Pgd are all closely localized in the top of the metabolic pathway and all appear to show an increase in southern-favored allele, but Pgm which is also at the top of the pathway shows the opposite pattern. This type of question directed at physiological context must await a more highly resolved study of many more genes. Nonetheless, the study of shifts in genetic variation in short and long-term contexts opens a new dimension to the study of natural selection and population structure.

Methods

Populations sampled

The clines for the 10 latitudinal collections from 1997 were reported by Sezgin et al.8 and Verrelli and Eanes29. The 2009/2010 cline data are described by Lavington et al.28. These data represent 18 collections made across the same latitudinal range as the 1997 collections. Many collections come from identical localities (Supplemental Table 1). The data points for Raleigh (collected 2005) and Sudbury, ON (collected in 2008) have been dropped from the analysis. The data used by Sezgin et al.8 for the Adh, Pgd, and G6pd genes comes from earlier work12,32, and these genes were resampled in 2009/2010 collections. We also include SNP frequency estimates for three recent collected European populations (Uppsala, Sweden, latitude 59.86; Kent, England, latitude 51.19; and Vienna, Austria, latitude 48.20) to provide further context. These are not included in any statistical analysis, but in most cases the European populations fall along the latitudinal regression trends.

Statistical analyses

The first statistical analysis uses a model, Yi = μ + αj + βXk + ε, where Yiis the ith dependent allele frequency, α is the effect of the sampling interval j, and Xk the kth latitude to test for interval effects. The changes in overall frequency difference between sample intervals and slopes of the regression against latitude were tested by t-test. Analysis was carried out in JMP® 11.2 on arcsine transformed frequencies49. The power of these tests was evaluated by power analyses (Supplemental Fig. 1). Our assessment of a cline depends on the significant presence of a linear regression of arcsine transformed frequency within year, or the combined years (in which each collection was treated as an independent point). This regression and its slope determine the tropical- or southern-biased allele in each SNP pair. The presence of a cline in any SNP places that locus in the clinal class.

Allele frequency estimation

The allele frequency estimates come from several methodologies including allozymes, restriction site polymorphism counts, base-specific Sanger sequencing for the 1997 samples, and bulk pyrosequencing peak estimation for the 2009/2010 samples. The bulk pyrosequencing peak estimation results in very accurate estimates of allele frequencies. We examined the correlation between the “true” input DGRP line SNP frequency estimates (based on original whole-genome sequences of individual inbreed lines50) with the estimated value in the bulk DNA preparation from that DGRP collection. The correlation was r = 0.98, and there is clearly no systemic bias in the estimation (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Cogni, R. et al. On the Long-term Stability of Clines in Some Metabolic Genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Sci. Rep. 7, 42766; doi: 10.1038/srep42766 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Adrion, J. R., Hahn, M. W. & Cooper, B. S. Revisiting classic clines in Drosophila melanogaster in the age of genomics. Trends in Genetics 31, 434–444, doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.05.006 (2015).

Klepsatel, P., Galikova, M., Huber, C. D. & Flatt, T. Similarities and Differences in Altitudinal Versus Latitudinal Variation for Morphological Traits in Drosophila Melanogaster. Evolution 68, 1385–1398, doi: 10.1111/evo.12351 (2014).

Fabian, D. K. et al. Spatially varying selection shapes life history clines among populations of Drosophila melanogaster from sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28, 826–840, doi: 10.1111/jeb.12607 (2015).

Machado, H. E. et al. Comparative population genomics of latitudinal variation in Drosophila simulans and Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular Ecology 25, 723–740, doi: 10.1111/mec.13446 (2016).

Hoffmann, A. A. & Weeks, A. R. Climatic selection on genes and traits after a 100 year-old invasion: a critical look at the temperate-tropical clines in Drosophila melanogaster from eastern Australia. Genetica 129, 133–147, doi: 10.1007/s10709-006-9010-z (2007).

Mettler, L. E., Voelker, R. A. & Mukai, T. Inversion Clines in Populations of Drosophila-Melanogaster. Genetics 87, 169–176 (1977).

Fabian, D. K. et al. Genome-wide patterns of latitudinal differentiation among populations of Drosophila melanogaster from North America. Molecular Ecology 21, 4748–4769, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05731.x (2012).

Sezgin, E. et al. Single-locus latitudinal clines and their relationship to temperate adaptation in metabolic genes and derived alleles in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 168, 923–931, doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027649 (2004).

Oakeshott, J. G., Chambers, G. K., Gibson, J. B. & Willcocks, D. A. Latitudinal Relationships of Esterase-6 And Phosphoglucomutase Gene-Frequencies in Drosophila-Melanogaster. Heredity 47, 385–396, doi: 10.1038/hdy.1981.99 (1981).

Knibb, W. R., Oakeshott, J. G. & Gibson, J. B. Chromosome inversion polymorphisms in drosophila-melanogaster.1. Latitudinal clines and associations between inversions in australasian populations. Genetics 98, 833–847 (1981).

Oakeshott, J. G. et al. Alcohol-Dehydrogenase and Glycerol-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Clines in Drosophila-Melanogaster on Different Continents. Evolution 36, 86–96, doi: 10.2307/2407970 (1982).

Oakeshott, J. G., Chambers, G. K., Gibson, J. B., Eanes, W. F. & Willcocks, D. A. Geographic-Variation In G6pd and Pgd Allele Frequencies in Drosophila-Melanogaster. Heredity 50, 67–72, doi: 10.1038/hdy.1983.7 (1983).

Oakeshott, J. G., McKechnie, S. W. & Chambers, G. K. Population-genetics of the metabolically related adh, gpdh and tpi polymorphisms in drosophila-melanogaster.1. Geographic-variation in gpdh and tpi allele frequencies in different continents. Genetica 63, 21–29, doi: 10.1007/bf00137461 (1984).

Turner, T. L., Levine, M. T., Eckert, M. L. & Begun, D. J. Genomic analysis of adaptive differentiation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 179, 455–473, doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083659 (2008).

Kolaczkowski, B., Kern, A. D., Holloway, A. K. & Begun, D. J. Genomic Differentiation Between Temperate and Tropical Australian Populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 187, 245–260, doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.123059 (2011).

Levine, M. T., Eckert, M. L. & Begun, D. J. Whole-Genome Expression Plasticity across Tropical and Temperate Drosophila melanogaster Populations from Eastern Australia. Molecular Biology and Evolution 28, 249–256, doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq197 (2011).

Reinhardt, J. A., Kolaczkowski, B., Jones, C. D., Begun, D. J. & Kern, A. D. Parallel Geographic Variation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 197, 361–373, doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.161463 (2014).

Bergland, A. O., Behrman, E. L., O’Brien, K. R., Schmidt, P. S. & Petrov, D. A. Genomic Evidence of Rapid and Stable Adaptive Oscillations over Seasonal Time Scales in Drosophila. Plos Genetics 10, doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004775 (2014).

Cogni, R. et al. The Intensity of Selection Acting on the Couch Potato Gene-Spatial-Temporal Variation in a Diapause Cline. Evolution 68, 538–548, doi: 10.1111/evo.12291 (2014).

Cogni, R. et al. Variation in Drosophila melanogaster central metabolic genes appears driven by natural selection both within and between populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 282, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2688 (2015).

Behrman, E. L., Watson, S. S., O’Brien, K. R., Heschel, M. S. & Schmidt, P. S. Seasonal variation in life history traits in two Drosophila species. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28, 1691–1704, doi: 10.1111/jeb.12690 (2015).

Duchen, P., Zivkovic, D., Hutter, S., Stephan, W. & Laurent, S. Demographic Inference Reveals African and European Admixture in the North American Drosophila melanogaster Population. Genetics 193, 291–301, doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.145912 (2013).

Yukilevich, R., Turner, T. L., Aoki, F., Nuzhdin, S. V. & True, J. R. Patterns and Processes of Genome-Wide Divergence Between North American and African Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 186, 219–U374, doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.117366 (2010).

Kao, J. Y., Zubair, A., Salomon, M. P., Nuzhdin, S. V. & Campo, D. Population genomic analysis uncovers African and European admixture in Drosophila melanogaster populations from the south-eastern United States and Caribbean Islands. Molecular Ecology 24, 1499–1509, doi: 10.1111/mec.13137 (2015).

Bergland, A. O., Tobler, R., Gonzalez, J., Schmidt, P. & Petrov, D. Secondary contact and local adaptation contribute to genome-wide patterns of clinal variation in Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular Ecology 25, 1157–1174, doi: 10.1111/mec.13455 (2016).

Umina, P. A., Weeks, A. R., Kearney, M. R., McKechnie, S. W. & Hoffmann, A. A. A rapid shift in a classic clinal pattern in Drosophila reflecting climate change. Science 308, 691–693, doi: 10.1126/science.1109523 (2005).

Schmidt, P. S. et al. An amino acid polymorphism in the couch potato gene forms the basis for climatic adaptation in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 16207–16211, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805485105 (2008).

Lavington, E. et al. A Small System-High-Resolution Study of Metabolic Adaptation in the Central Metabolic Pathway to Temperate Climates in Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular Biology and Evolution 31, 2032–2041, doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu146 (2014).

Verrelli, B. C. & Eanes, W. F. Clinal variation for amino acid polymorphisms at the Pgm locus in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 157, 1649–1663 (2001).

Eanes, W. F., Kirchner, M. & Yoon, J. Evidence for Adaptive Evolution of The G6pd Gene in The Drosophila-Melanogaster and Drosophila-Simulans Lineages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 90, 7475–7479, doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7475 (1993).

Berger, E. M. Temporal Survey Of Allelic Variation In Natural And Laboratory Populations Of Drosophila-Melanogaster. Genetics 67, 121-& (1971).

Berry, A. & Kreitman, M. Molecular Analysis of an Allozyme Cline - Alcohol-Dehydrogenase in Drosophila-Melanogaster on The East-Coast of North-America. Genetics 134, 869–893 (1993).

Paaby, A. B., Bergland, A. O., Behrman, E. L. & Schmidt, P. S. A highly pleiotropic amino acid polymorphism in the Drosophila insulin receptor contributes to life-history adaptation. Evolution 68, 3395–3409, doi: 10.1111/evo.12546 (2014).

Vasemagi, A. The adaptive hypothesis of clinal variation revisited: Single-locus clines as a result of spatially restricted gene flow. Genetics 173, 2411–2414, doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.059881 (2006).

Meirmans, P. G. The trouble with isolation by distance. Molecular Ecology 21, 2839–2846, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05578.x (2012).

Keller, A. Drosophila melanogaster’s history as a human commensal. Current Biology 17, R77–R81, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.031 (2007).

Kapun, M., Van Schalkwyk, H., McAllister, B., Flatt, T. & Schlotterer, C. Inference of chromosomal inversion dynamics from Pool-Seq data in natural and laboratory populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular Ecology 23, 1813–1827, doi: 10.1111/mec.12594 (2014).

Beisswanger, S., Stephan, W. & De Lorenzo, D. Evidence for a selective sweep in the wapl region of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 172, 265–274, doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.049346 (2006).

Bradshaw, W. E. & Holzapfel, C. M. Genetic response to rapid climate change: it’s seasonal timing that matters. Molecular Ecology 17, 157–166, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03509.x (2008).

Anderson, W. W. et al. 4 Decades of Inversion Polymorphism in Drosophila-Pseudoobscura. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 88, 10367–10371, doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10367 (1991).

Balanya, J., Oller, J. M., Huey, R. B., Gilchrist, G. W. & Serra, L. Global genetic change tracks global climate warming in Drosophila subobscura. Science 313, 1773–1775, doi: 10.1126/science.1131002 (2006).

Levitan, M. & Etges, W. J. Climate change and recent genetic flux in populations of Drosophila robusta. Bmc Evolutionary Biology 5, doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-4 (2005).

Balanya, J., Huey, R. B., Gilchrist, G. W. & Serra, L. The chromosomal polymorphism of Drosophila subobscura: a microevolutionary weapon to monitor global change. Heredity 103, 364–367, doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.86 (2009).

Rodriguez-Trelles, F., Tarrio, R. & Santos, M. Genome-wide evolutionary response to a heat wave in Drosophila. Biology Letters 9, doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0228 (2013).

Bradshaw, W. E. & Holzapfel, C. M. Climate change - Evolutionary response to rapid climate change. Science 312, 1477–1478, doi: 10.1126/science.1127000 (2006).

Dobzhansky, T. Genetics of natural populations IX. Temporal changes in the composition of populations of Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics 28, 162–186 (1943).

Anderson, A. R., Hoffmann, A. A., McKechnie, S. W., Umina, P. A. & Weeks, A. R. The latitudinal cline in the In(3R)Payne inversion polymorphism has shifted in the last 20 years in Australian Drosophila melanogaster populations. Molecular Ecology 14, 851–858, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02445.x (2005).

Kapun, M., Fabian, D. K., Goudet, J. & Flatt, T. Genomic Evidence for Adaptive Inversion Clines in Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular Biology and Evolution 33, 1317–1336, doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw016 (2016).

Sokal, R. R. R. F. Biometry. (Freeman, 2012).

Mackay, T. F. C. et al. The Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel. Nature 482, 173–178, doi: 10.1038/nature10811 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Eugene Brud for a careful reading and useful comments on the manuscript. We would also like to thank John True and Joe Lachance for three additional collections from New York. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant (GM090094) to Walter Eanes and John True and Collaborative National Foundation Science grants (DEB0921372) to WFE and (DEB0542859 and DEB0921307) to PSS. RC is founded by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant# 2013/25991-0 and CNPq (307015/2015-7).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C., W.F.E., P.S.S. designed the research. R.C., K.K., S.K., E.L., E.L.B., K.R.O., P.S.S. performed the research. R.C. and W.F.E. analyzed the data and wrote the main manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cogni, R., Kuczynski, K., Koury, S. et al. On the Long-term Stability of Clines in Some Metabolic Genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Sci Rep 7, 42766 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42766

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42766

This article is cited by

-

Wolbachia reduces virus infection in a natural population of Drosophila

Communications Biology (2021)

-

Genome-wide patterns of local adaptation in Western European Drosophila melanogaster natural populations

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.