Abstract

Functional brain imaging studies and non-invasive brain stimulation methods have shown the importance of the left supramarginal gyrus (SMG) for pitch memory. The extent to which this brain region plays a crucial role in memory for other auditory material remains unclear. Here, we sought to investigate the role of the left and right SMG in pitch and rhythm memory in non-musicians. Anodal or sham transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) was applied over the left SMG (Experiment 1) and right SMG (Experiment 2) in two different sessions. In each session participants completed a pitch and rhythm recognition memory task immediately after tDCS. A significant facilitation of pitch memory was revealed when anodal stimulation was applied over the left SMG. No significant effects on pitch memory were found for anodal tDCS over the right SMG or sham condition. For rhythm memory the opposite pattern was found; anodal tDCS over the right SMG led to an improvement in performance, but anodal tDCS over the left SMG had no significant effect. These results highlight a different hemispheric involvement of the SMG in auditory memory processing depending on auditory material that is encoded.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pitch and rhythm are two important factors for music perception and cognition1. They are related to language production and comprehension2,3,4, and are associated with auditory verbal and non-verbal memory1,5,6. With this in mind, factors contributing to pitch and rhythm memory have received considerable interest, and functional brain imaging studies have highlighted underlying neural structures for pitch and rhythm memory. For pitch memory a complex neural network has been revealed including frontal, temporal and parietal areas7,8,9,10. Of particular relevance to the current study is the supramarginal gyrus (SMG), which has been shown to relate to inter-individual variation in pitch memory performance11. Rhythm memory has been associated with a similar frontal-parietal network (including brain activation in the supramarginal gyrus) as pitch memory9,12,13, as well as activity in the cerebellum and supplementary motor area12,13, anterior insular cortex and left anterior cingulate gyrus9.

Investigations of pitch and rhythm memory in the same study are sparse, and thus overlapping and separable brain areas related to rhythm and pitch memory are fairly unknown. Jerde and colleagues9 explored the neural correlates of pitch and rhythm working memory in non-musicians and revealed distinct neural circuits for each process. Whereas pitch memory showed activation in a right hemisphere network of frontal, parietal and temporal areas, rhythm memory was associated with activation in the cerebellar hemispheres and vermis, right anterior insular cortex, and left anterior cingulate gyrus. Additionally, and importantly in the context of the present study, the SMG has been shown to have differential laterisation of function according to whether rhythm or pitch word devision wrong tasks were completed. Jerde and colleagues revealed activation in the inferior parietal lobe (the area of the SMG) bilaterally for pitch memory and only right hemisphere activation for rhythm memory9.

Further evidence for a distinction of rhythm and pitch processing can be gained from studies investigating impairments in each process. For instance, in congenital amusia (individuals with deficits in music processing and memory) there are a number of cases where individuals show selective impairment in pitch processing, but not rhythm processing14,15. Additionally, brain-lesion studies exploring rhythm and pitch discrimination have shown that rhythm perception can be disturbed, whereas pitch perception is intact and vice versa16,17,18,19. Taken together, these studies indicate that pitch and rhythm processing can be dissociated, and therefore neural processes related to encoding pitch and rhythm may rely on distinct neural circuits.

With regards to the neural network for pitch and rhythm memory, brain imaging alone cannot tell us about causal relationships between brain areas and behaviour. For this alternative methods that permit the investigation of modulations in brain activity are more powerful (e.g. lesions20,21,22; brain stimulation23,24,25,26,27,28). In this context, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) has been shown to be a promising tool to investigate the causal role of specific brain areas for cognitive tasks29,30. TDCS uses two stimulation modes, anodal and cathodal stimulation. In most studies, anodal tDCS enhances cortical excitability in the targeted area, while cathodal tDCS typically suppresses cortical excitability31,32,33,34. However, also some contrary effects depending on the duration and intensity of the stimulation input have been shown more recently35 and there is an ongoing discussion about the reliability and efficiency of tDCS protocols depending on a number of trait and state variables36,37. With regards to pitch memory, studies using non-invasive brain stimulation methods have consistently revealed a critical role for the left SMG for pitch memory in non-musicians38,39,40,41. To date, no brain stimulation studies have been conducted to examine the neural mechanisms of rhythm memory. Therefore we sought to investigate this for the first time in the present study.

More specifically, the aim of this study was to examine the role of the left and right SMG for rhythm and pitch memory. As noted above, prior brain stimulation work has indicated a causal role for the left SMG in pitch memory38,41, but whether this region plays a similar role in rhythm memory remains unclear. Previous functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) findings on the role of the SMG in rhythm memory paint a mixed picture: in one study bilateral activation of the SMG was found13, in others activation of the right SMG has been reported9,12,42, and another study highlighted left hemisphere activation of the SMG43. We sought to examine the influence of tDCS targeted at left and right SMG on rythym and pitch memory to disentangle the hemispheric specialisation of the SMG for rhythm and pitch memory. Two experiments were conducted. In Experiment 1 we investigated whether the left SMG is specifically involved in pitch memory or whether it is also significant in another auditory memory domain, such as rhythm memory. In Experiment 2, we explored whether the right SMG could be linked to rhythm memory. Participants took part in two sessions and either anodal or sham tDCS over the left SMG (Experiment 1) and right SMG (Experiment 2) was applied. After stimulation, participants completed a pitch and rhythm span task. Based on previous research38,40, an improvement of pitch memory after anodal tDCS over the left SMG was expected. Regarding rhythm memory, an effect of anodal tDCS on memory performance was hypothesised as brain imaging studies show the involvement of the SMG for rhythm memory12,13,43, but the lateralisation of the effect is less predictable.

Results

An overall mixed-factor ANOVA with the within-subject variables stimulation (sham vs. anodal) and task (pitch span vs. rhythm span) and the between-subject variable group (left SMG group vs. right SMG group) was conducted. The analysis revealed a significant main effect for task [F(1,40) = 167.98, p < 0.001,  = 0.808] and non-significant main effects for stimulation [F(1,40) = 1.77, p = 0.191,

= 0.808] and non-significant main effects for stimulation [F(1,40) = 1.77, p = 0.191,  = 0.042] and group [F(1,28) = 2.82, p = 0.104,

= 0.042] and group [F(1,28) = 2.82, p = 0.104,  = 0.091]. A trend for the stimulation * group interaction was found [F(1,40) = 3.61, p = 0.065,

= 0.091]. A trend for the stimulation * group interaction was found [F(1,40) = 3.61, p = 0.065,  = 0.083] and there were non-significant results for the task * group interaction [F(1,40) = 1.14, p = 0.291,

= 0.083] and there were non-significant results for the task * group interaction [F(1,40) = 1.14, p = 0.291,  = 0.028] and stimulation * task interaction [F(1,40) = 0.059, p = 0.809,

= 0.028] and stimulation * task interaction [F(1,40) = 0.059, p = 0.809,  = 0.001]. Importantly, the three-way stimulation * task * group interaction was significant [F(1,40) = 11.33, p = 0.002,

= 0.001]. Importantly, the three-way stimulation * task * group interaction was significant [F(1,40) = 11.33, p = 0.002,  = 0.221].

= 0.221].

In order to disentangle this interaction, two ANOVAs were calculated separately for each group with the within-subject variables stimulation and task. In the group receiving stimulation over the left SMG (Experiment 1) significant main effects of stimulation [F(1,19) = 4.80, p = 0.041,  = 0.202] and task [F(1,19) = 106.46, p < 0.001,

= 0.202] and task [F(1,19) = 106.46, p < 0.001,  = 0.849] were revealed, indicating that overall participants were slightly better on both tasks in the anodal condition compared to sham condition, and that participants were better at the pitch memory task compared to rhythm memory performance. Additionally, the stimulation * task interaction was also significant [F(1,19) = 4.52, p = 0.047,

= 0.849] were revealed, indicating that overall participants were slightly better on both tasks in the anodal condition compared to sham condition, and that participants were better at the pitch memory task compared to rhythm memory performance. Additionally, the stimulation * task interaction was also significant [F(1,19) = 4.52, p = 0.047,  = 0.192]. To examine this further, planned paired samples t-tests with Bonferroni correction comparing performances after sham and anodal stimulation on the pitch memory and rhythm memory task were conducted. The comparison of pitch memory performance between sham and anodal tDCS revealed a significant difference [t(19) = 2.61, p = 0.017,

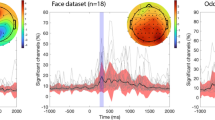

= 0.192]. To examine this further, planned paired samples t-tests with Bonferroni correction comparing performances after sham and anodal stimulation on the pitch memory and rhythm memory task were conducted. The comparison of pitch memory performance between sham and anodal tDCS revealed a significant difference [t(19) = 2.61, p = 0.017,  = 0.264] (Fig. 1). The participants performed significantly better on the pitch memory span task after receiving anodal tDCS over the left SMG compared to sham stimulation. No difference was found for the rhythm task [t(19) = 0.064, p = 0.950,

= 0.264] (Fig. 1). The participants performed significantly better on the pitch memory span task after receiving anodal tDCS over the left SMG compared to sham stimulation. No difference was found for the rhythm task [t(19) = 0.064, p = 0.950,  = 0.021].

= 0.021].

In Experiment 1 anodal tDCS over the left SMG led to a facilitation of pitch memory, whereas rhythm memory was not affected. However, anodal tDCS over the right SMG improved rhythm memory in Experiment 2, whereas pitch memory was not significantly modulated by the stimulation. The error bars represent SEM.

For Experiment 2 (stimulation over the right SMG) a non-significant main effect of stimulation [F(1,21) = 0.18, p = 0.678,  = 0.008] and a significant main effect of task [F(1,21) = 67.10, p < 0.001,

= 0.008] and a significant main effect of task [F(1,21) = 67.10, p < 0.001,  = 0.762] were found. The stimulation * task interaction was significant [F(1,21) = 7.02, p = 0.015,

= 0.762] were found. The stimulation * task interaction was significant [F(1,21) = 7.02, p = 0.015,  = 0.2505]. A paired-samples t-test with Bonferroni correction revealed that rhythm memory performance was facilitated when receiving anodal tDCS over the right SMG [t(21) = 2.78, p = 0.011,

= 0.2505]. A paired-samples t-test with Bonferroni correction revealed that rhythm memory performance was facilitated when receiving anodal tDCS over the right SMG [t(21) = 2.78, p = 0.011,  = 0.269] (Fig. 1). No significant modulation effect was found for pitch memory [t(21) = 1.68, p = 0.108,

= 0.269] (Fig. 1). No significant modulation effect was found for pitch memory [t(21) = 1.68, p = 0.108,  = 0.118].

= 0.118].

In addition, separate ANOVAs for each task were conducted with stimulation and group as the independent variables. For the pitch memory task the analysis showed non-significant main effects of stimulation [F(1,40) = 0.39, p = 0.538,  = 0.010] and group [F(1,40) = 1.95, p = 0.170,

= 0.010] and group [F(1,40) = 1.95, p = 0.170,  = 0.047] and a significant stimulation * group interaction [F(1,40) = 12.5, p = 0.004,

= 0.047] and a significant stimulation * group interaction [F(1,40) = 12.5, p = 0.004,  = 0.185]. The ANOVA for the rhythm task revealed a trend for the factor stimulation [F(1,40) = 2.97, p = 0.093,

= 0.185]. The ANOVA for the rhythm task revealed a trend for the factor stimulation [F(1,40) = 2.97, p = 0.093,  = 0.069], a non-significant effect of group [F(1,40) = 0.57, p = 0.453,

= 0.069], a non-significant effect of group [F(1,40) = 0.57, p = 0.453,  = 0.014] and a non-significant stimulation * group interaction [F(1,40) = 2.60, p = 0.115,

= 0.014] and a non-significant stimulation * group interaction [F(1,40) = 2.60, p = 0.115,  = 0.061].

= 0.061].

Discussion

The aim of the study was to investigate the involvement of the left and right SMG for pitch and rhythm memory, and to explore whether a hemispheric distinction can be found depending on the task. Experiment 1 revealed that anodal tDCS over the left SMG significantly facilitated pitch memory, whereas rhythm memory was not affected. Experiment 2 showed that anodal tDCS over the right SMG facilitated rhythm memory performance, whereas pitch memory performance was not modulated. The study highlights a different hemispheric involvement of the SMG for rhythm and pitch memory.

The finding that the left but not right SMG is causally involved in pitch memory is as hypothesised and in accordance with previous studies38,40,41. Since rhythm memory was not modulated by tDCS over the left SMG, the results of Experiment 1 also reveal that the left SMG is not causally involved throughout the auditory memory domain. The selective improvement of pitch but not rhythm memory suggests that the function of the left SMG is restricted to pitch information in auditory memory. As the left SMG has also been shown to be involved in verbal memory tasks44,45, one might also conclude that the left SMG relates to general pitch-based memory functions such as tonal pitch or intonation memory. This will be an interesting avenue to explore in future studies. For instance, does tDCS to the left SMG specifically modulate pitch memory span, versus verbal span. In previous studies, we have shown that tDCS over the left and right SMG did not modulate memory performance on a visual memory task38,40, but future work should address the role of the left SMG in verbal memory span performance.

When anodal tDCS was applied over the right SMG in Experiment 2, a different pattern was revealed. No modulation was shown for pitch memory which is in accordance with a previous study of our group40. Interestingly, improved performance on the rhythm memory task was found, indicating that the right SMG is related to rhythm memory. This is in accordance with fMRI studies showing a dominant rightward activation of the SMG for rhythm discrimination and memory12,42. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study revealing a causal relationship of a particular brain area (i.e. the right SMG) for rhythm memory by means of non-invasive brain stimulation.

The study shows a dissociation of the involvement of the left and right SMG for pitch and rhythm memory. Hemispheric differences of the involvement of the SMG have also been shown depending on expertise. In a previous study we showed that cathodal tDCS over the left SMG led to a deterioration of pitch memory performance in non-musicians, whereas musicians showed a decline in pitch memory after cathodal tDCS over the right SMG40. This highlights a hemispheric shift of the involvement of the SMG with musical training, which may be due to different strategies used for memorising the pitch information between non-musicians and musicians. Furthermore, Herdener et al.46 revealed that rhythm processing activates a network predominantly in the right hemisphere, but that highly trained drummers additionally show activation in the left SMG. These authors highlight a link between the left SMG and linguistic syntax processing, which would suggest that drummers try to give a meaning to the rhythmical cues. It would be interesting to perform the present study protocol with musicians as participants in order to further investigate the significance of the left and right SMG for pitch and rhythm memory taking into account musical expertise.

As it is expected that the tDCS effects are the strongest under the active electrode, the results of our study highlight the significance of the left SMG for pitch memory as well as linking the right SMG to rhythm memory. It is, however, possible that the effects also spread to brain areas that are functionally connected with the stimulated area47, and that this also influences the behavioural performance. As the literature highlights a strong connection of the right inferior and frontal areas for rhythm memory12,13, it might be that the memory enhancement may also be due to an increased interconnection of the right SMG to frontal areas. For pitch memory the spread of activation could have strengthened the connections of the left SMG to frontal or auditory cortices11. Assessing the impact of brain stimulation on functional interactions within and between brain networks is an important next step for future research27.

In sum the study highlights a hemispheric dissociation of the SMG for different auditory materials in non-musicians. Whereas the significance of the left SMG can be linked to pitch memory performance, the right SMG seems to be involved in rhythm memory.

Methods

Participants

Forty-four right-handed non-musicians (10 male) were recruited for this study. Two participants were excluded for the analysis. One participant indicated that she used the keys the wrong way round in the rhythm span task and one participant was excluded as her rhythm memory performance during sham stimulation was identified as an extreme outlier using the Grubbs Test48. The remaining sample for the analysis consisted of 20 participants (5 male) in Experiment 1 and 22 participants (5 male) in Experiment 2. Participants did not play an instrument currently and had less than two years of musical training in the past. The minimal musical training exposure was confirmed by a low mean score of 14.17 points (SD = 5.04) in the Musical Training Dimension (possible range 7–49, see Material for more information) of the German version of the Goldsmiths Musical Sophistication Index (Gold-MSI)49,50. The samples of both experiments were matched by age, gender and Gold-MSI score (see Table 1 for demographical details).

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Department of the Heinrich-Heine-University in Düsseldorf and the methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave their informed written consent to take part prior to the study.

Material

Pitch and rhythm memory task

In order to measure pitch memory abilities, the pitch span task51 was used. This task measures pitch memory capacity by identifying the maximum span of tones the individual participant can keep in mind. The task uses 10 triangle-waveform tones (equally tempered, whole tone steps) with fundamental pitches ranging from 262 Hz (C4) to 741 Hz (F#5) which are 500 msec long and which are presented with 383 msec pause between each other. To begin with participants hear two pitch sequences which are two tones long with a 2 sec pause between sequences and the task is to indicate whether the two sequences are the same or different. The sequence length increases and decreases using an adaptive staircase procedure. When participants give two correct answers, one tone is added and when participants give one wrong answer, one tone is taken away. By using this procedure, participants are pushed to their limit of pitch memory capacity. The task is completed when 6 reversals are reached51.

For the evaluation of rhythm memory, the rhythm span task52 was used. This task was developed following the experimental parameters of the described pitch memory task. Instead of presenting the participants with tone sequences, two rhythm sequences were played and the task was to judge whether the rhythms were the same or different. Six rhythm elements were created. Elements were 1 second long (spanning over one quarter note) and contained one to three units (quarter notes, eighth notes, sixteenth notes and eighth note triplets), all presented on the same pitch. As the precise timing is important, 20 sequences were created (10 same and 10 different) for each sequence lengths (2 to 10 elements). Rhythm elements were randomly sampled and the span task followed the same adaptive staircase procedure as the pitch memory task. Participants were instructed to press the left command button if they thought the sequences were the same and the right command button for different sequences52.

Gold-MSI questionnaire

The German version of the self-report questionnaire of the Goldsmiths Musical Sophistication Index v1.0 (Gold-MSI)49,50 was used to evaluate musical training and sophistication in order to ensure that only non-musicians took part. The questionnaire evaluates musical behaviour and engagement and participants are asked to rate 38 statements using a seven-point scale. The Gold-MSI comprises a general factor ‘Musical Sophistication’ as well as five individual dimensions: Active Engagement, Perceptual Abilities, Musical Training, Emotions and Singing Abilities. The dimension of interest for this study is Musical Training which includes seven items and a possible score of 7–49 points.

TDCS parameters

TDCS was applied over the left SMG in Experiment 1 and the right SMG in Experiment 2. In Experiment 1, the left SMG was identified using CP3 of the international 10–20 system for electroencephalogram electrode placement. In Experiment 2, the right SMG was located using CP4. This method has been used successfully in previous studies40,41. An active electrode (5 cm × 5 cm = 25 cm2) was placed over the targeted site, left or right SMG respectively, and the reference electrode (5 cm × 7 cm = 35 cm2) was adjusted over the contralateral supraorbital area. The electrodes were covered in saline-soaked sponges and fixed on the scalp using self-adhesive bandages. For the active condition 15 minutes of anodal tDCS (with 30 seconds fade-in and fade-out) with an intensity of 2 mA was applied. For the sham condition, an identical set-up was used but the stimulation only lasted for 30 seconds (with additional 30 seconds fade-in and fade-out). This evokes the sensation of being stimulated but does not lead to any neurophysiological changes53.

Procedure

The study comprises two experiments which were identical in their procedure except that a different target brain area, left or right SMG, was stimulated. In Experiment 1, anodal or sham tDCS was applied over the left SMG and in Experiment 2 stimulation was applied over the right SMG.

Each participant took part in two sessions and either received anodal or sham stimulation over the targeted area. The order of stimulation was counterbalanced between participants. After signing the consent form the electrodes were placed on the scalp and the stimulation began. During the 15 minutes of stimulation participants were asked to sit back and relax. As soon as the stimulation finished, the participants completed the pitch and rhythm span task. The order of tasks was counterbalanced between participants. At the end of the first session the participants filled in the Gold-MSI questionnaire.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Schaal, N. K. et al. Hemispheric differences between left and right supramarginal gyrus for pitch and rhythm memory. Sci. Rep. 7, 42456; doi: 10.1038/srep42456 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Krumhansl, C. L. Rhythm and pitch in music cognition. Psychological Bulletin 126, 159–179, doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.126.1.159 (2000).

Nazzi, T., Bertoncini, J. & Mehler, J. Language discrimination by newborns: Toward an understanding of the role of rhythm. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Human Perception and Performance 24, 756–766, doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.24.3.756 (1998).

Ramus, F., Nespor, M. & Mehler, J. Correlates of linguistic rhythm in the speech signal. Cognition 73, 265–292, doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(99)00058-x (1999).

Posedel, J., Emery, L., Souza, B. & Fountain, C. Pitch perception, working memory, and second-language phonological production. Psychology of Music 40, 508–517, doi: 10.1177/0305735611415145 (2012).

Slater, J. & Kraus, N. The role of rhythm in perceiving speech in noise: a comparison of percussionists, vocalists and non-musicians. Cognitive Processing 17, 79–87, doi: 10.1007/s10339-015-0740-7 (2016).

Peretz, I. & Zatorre, R. J. In Annual Review of Psychology Vol. 56 Annual Review of Psychology 89–114 (Annual Reviews, 2005).

Zatorre, R. J., Evans, A. C. & Meyer, E. Neural mechanisms underlying melodic perception and memory for pitch. Journal of Neuroscience 14, 1908–1919 (1994).

Koelsch, S. et al. Functional Architecture of Verbal and Tonal Working Memory: An fMRI Study. Human Brain Mapping 30, 859–873, doi: 10.1002/hbm.20550 (2009).

Jerde, T. A., Childs, S. K., Handy, S. T., Nagode, J. C. & Pardo, J. V. Dissociable systems of working memory for rhythm and melody. Neuroimage 57, 1572–1579, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.061 (2011).

Schulze, K., Zysset, S., Mueller, K., Friederici, A. D. & Koelsch, S. Neuroarchitecture of Verbal and Tonal Working Memory in Nonmusicians and Musicians. Human Brain Mapping 32, 771–783, doi: 10.1002/hbm.21060 (2011).

Gaab, N., Gaser, C., Zähle, T., Jäncke, L. & Schlaug, G. Functional anatomy of pitch memory - an fMRI study with sparse temporal sampling. Neuroimage 19, 1417–1426, doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00224-6 (2003).

Konoike, N. et al. Temporal and Motor Representation of Rhythm in Fronto-Parietal Cortical Areas: An fMRI Study. Plos One 10, 19, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130120 (2015).

Konoike, N. et al. Rhythm information represented in the fronto-parieto-cerebellar motor system. Neuroimage 63, 328–338, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.002 (2012).

Phillips-Silver, J., Toiviainen, P., Gosselin, N. & Peretz, I. Amusic does not mean unmusical: Beat perception and synchronization ability despite pitch deafness. Cognitive Neuropsychology 30, 311–331, doi: 10.1080/02643294.2013.863183 (2013).

Hyde, K. L. & Peretz, I. Brains that are out of tune but in time. Psychological Science 15, 356–360, doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00683.x (2004).

Peretz, I. Processing of Local and Global Musical Information by Unilateral Brain-damaged Patients. Brain 113, 1185–1205, doi: 10.1093/brain/113.4.1185 (1990).

Peretz, I. Auditoy Anatolia for Meldodies. Cognitive Neuropsychology 10, 21–56, doi: 10.1080/02643299308253455 (1993).

Di Pietro, M., Laganaro, M., Leemann, B. & Schnider, A. Receptive amusia: temporal auditory processing deficit in a professional musician following a left temporo-parietal lesion. Neuropsychologia 42, 868–877, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.12.004 (2004).

Piccirilli, M., Sciarma, T. & Luzzi, S. Modularity of music: evidence from a case of pure amusia. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 69, 541–545, doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.4.541 (2000).

Bolandzadeh, N., Davis, J. C., Tam, R., Handy, T. C. & Liu-Ambrose, T. The association between cognitive function and white matter lesion location in older adults: a systematic review. Bmc Neurology 12, 10, doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-126 (2012).

Tramo, M. J., Shah, G. D. & Braida, L. D. Functional role of auditory cortex in frequency processing and pitch perception. Journal of Neurophysiology 87, 122–139 (2002).

Dykstra, A. R., Koh, C. K., Braida, L. D. & Tramo, M. J. Dissociation of Detection and Discrimination of Pure Tones following Bilateral Lesions of Auditory Cortex. Plos One 7, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044602 (2012).

Herrmann, C. S., Rach, S., Neuling, T. & Struber, D. Transcranial alternating current stimulation: a review of the underlying mechanisms and modulation of cognitive processes. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7, 13, doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00279 (2013).

Miniussi, C., Harris, J. A. & Ruzzoli, M. Modelling non-invasive brain stimulation in cognitive neuroscience. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 37, 1702–1712, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.014 (2013).

Sack, A. T. Transcranial magnetic stimulation, causal structure-function mapping and networks of functional relevance. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 16, 593–599, doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.06.016 (2006).

Santiesteban, I., Banissy, M. J., Catmur, C. & Bird, G. Functional lateralization of temporoparietal junction - imitation inhibition, visual perspective-taking and theory of mind. European Journal of Neuroscience 42, 2527–2533, doi: 10.1111/ejn.13036 (2015).

Luft, C. D. B., Pereda, E., Banissy, M. J. & Bhattacharya, J. Best of both worlds: promise of combining brain stimulation and brain connectome. Frontiers in systems neuroscience 8, 132, doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00132 (2014).

Juan, C. H. & Muggleton, N. G. Brain stimulation and inhibitory control. Brain Stimulation 5, 63–69, doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2012.03.012 (2012).

Nitsche, M. A. & Paulus, W. Sustained excitability elevations induced by transcranial DC motor cortex stimulation in humans. Neurology 57, 1899–1901 (2001).

Antal, A. et al. Direct current stimulation over V5 enhances visuomotor coordination by improving motion perception in humans. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 16, 521–527, doi: 10.1162/089892904323057263 (2004).

Kadosh, R. C., Soskic, S., Iuculano, T., Kanai, R. & Walsh, V. Modulating Neuronal Activity Produces Specific and Long-Lasting Changes in Numerical Competence. Current Biology 20, 2016–2020, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.007 (2010).

Ladeira, A. et al. Polarity-Dependent Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Effects on Central Auditory Processing. Plos One 6, 6, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025399 (2011).

Nitsche, M. A. & Paulus, W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. Journal of Physiology-London 527, 633–639, doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00633.x (2000).

Cohen Kadosh, R., Soskic, S., Iuculano, T., Kanai, R. & Walsh, V. Modulating Neuronal Activity Produces Specific and Long-Lasting Changes in Numerical Competence. Current Biology 20, 2016–2020, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.007 (2010).

Batsikadze, G., Moliadze, V., Paulus, W., Kuo, M. F. & Nitsche, M. A. Partially non-linear stimulation intensity-dependent effects of direct current stimulation on motor cortex excitability in humans. Journal of Physiology-London 591, 1987–2000, doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.249730 (2013).

Horvath, J. C., Carter, O. & Forte, J. D. Transcranial direct current stimulation: five important issues we aren’t discussing (but probably should be). Frontiers in systems neuroscience 8, 2–2, doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00002 (2014).

Horvath, J. C., Forte, J. D. & Carter, O. Evidence that transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) generates little-to-no reliable neurophysiologic effect beyond MEP amplitude modulation in healthy human subjects: A systematic review. Neuropsychologia 66, 213–236, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.11.021 (2015).

Schaal, N. K., Williamson, V. J. & Banissy, M. J. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation over the supramarginal gyrus facilitates pitch memory. European Journal of Neuroscience 38, 3513–3518, doi: 10.1111/ejn.12344 (2013).

Schaal, N. K. et al. A causal involvement of the left supramarginal gyrus during the retention of musical pitches. Cortex 64, 310–317, doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.11.011 (2015).

Schaal, N. K. et al. Pitch Memory in Nonmusicians and Musicians: Revealing Functional Differences Using Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation. Cerebral Cortex 25, 2774–2782, doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu075 (2015).

Vines, B. W., Schnider, N. M. & Schlaug, G. Testing for causality with transcranial direct current stimulation: pitch memory and the left supramarginal gyrus. Neuroreport 17, 1047–1050, doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000223396.05070.a2 (2006).

Thaut, M. H., Trimarchi, P. D. & Parsons, L. M. Human brain basis of musical rhythm perception: common and distinct neural substrates for meter, tempo, and pattern. Brain sciences 4, 428–452, doi: 10.3390/brainsci4020428 (2014).

Ellis, R. J., Bruijn, B., Norton, A. C., Winner, E. & Schlaug, G. Training-mediated leftward asymmetries during music processing: A cross-sectional and longitudinal fMRI analysis. Neuroimage 75, 97–107, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.045 (2013).

Romero, L., Walsh, V. & Papagno, C. The neural correlates of phonological short-term memory: A repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 18, 1147–1155, doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.7.1147 (2006).

Paulesu, E., Frith, C. D. & Frackowiak, R. S. J. The neural correlates of the verbal component of working memory. Nature 362, 342–345, doi: 10.1038/362342a0 (1993).

Herdener, M. et al. Jazz Drummers Recruit Language-Specific Areas for the Processing of Rhythmic Structure. Cerebral Cortex 24, 836–843, doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs367 (2014).

Holland, R. et al. Speech Facilitation by Left Inferior Frontal Cortex Stimulation. Current Biology 21, 1403–1407, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.021 (2011).

Grubbs, F. E. Vol. 11, 1–21 (Technometrics, 1969).

Müllensiefen, D., Gingras, B., Musil, J. & Stewart, L. The Musicality of Non-Musicians: An Index for Assessing Musical Sophistication in the General Population. Plos One 9, 23, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089642 (2014).

Schaal, N. K., Bauer, A.-K. R. & Müllensiefen, D. Der Gold-MSI: Replikation und Validierung eines Fragebogeninstrumentes zur Messung Musikalischer Erfahrenheit anhand einer deutschen Stichprobe. Musicae Scientiae 18, 423–447, doi: 10.1177/1029864914541851 (2014).

Williamson, V. J. & Stewart, L. Memory for pitch in congenital amusia: Beyond a fine-grained pitch discrimination problem. Memory 18, 657–669, doi: 10.1080/09658211.2010.501339 (2010).

Schaal, N. K., Banissy, M. J. & Lange, K. The Rhythm Span Task: Comparing Memory Capacity for Musical Rhythms in Musicians and Non-Musicians. Journal of New Music Research 44, 3–10, doi: 10.1080/09298215.2014.937724 (2015).

Gandiga, P. C., Hummel, F. C. & Cohen, L. G. Transcranial DC stimulation (OCS): A tool for double-blind sham-controlled clinical studies in brain stimulation. Clinical Neurophysiology 117, 845–850, doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.12.003 (2006).

Acknowledgements

Michael J. Banissy is supported by the ESRC [ES/K00882X/1] and European Commission [CREAM project under Grant Agreement no. 612022]. We would like to thank Nina Heins and Niklas Wessendorf for their help with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K.S. and M.J.B. conceived the study concept. All authors contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation. N.K.S. drafted the manuscript, and B.P. and M.J.B. provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Schaal, N., Pollok, B. & Banissy, M. Hemispheric differences between left and right supramarginal gyrus for pitch and rhythm memory. Sci Rep 7, 42456 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42456

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42456

This article is cited by

-

Resting-state functional connectivity in an auditory network differs between aspiring professional and amateur musicians and correlates with performance

Brain Structure and Function (2023)

-

Effect of berry-based supplements and foods on cognitive function: a systematic review

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Brain Reactions to Opening and Closing the Eyes: Salivary Cortisol and Functional Connectivity

Brain Topography (2022)

-

FMRI-based identity classification accuracy in left temporal and frontal regions predicts speaker recognition performance

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Musical imagery depends upon coordination of auditory and sensorimotor brain activity

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.