Abstract

Novel intermediate oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridiniums were facilely prepared from 2-(2,2-dimethoxyethoxy)-pyridines via acid promoted intramolecular cyclization. Sequentially, the quaternary ammonium salts were treated with different nucleophiles for performing regioselective metal-free C-O and C-N bond-cleaving to afford prevalent heterocyclic structures of N-substituted pyridones and 2-substituted pyridines. The reaction mechanism and regioselectivity were then systematically explored by quantum chemistry calculations at B3LYP/6-31 g(d) level. The calculated free energy barrier of the reactions revealed that aniline and aliphatic amines (e.g., methylamine) prefer to attack C8 of intermediate 4a, affording N-substituted pyridones, while phenylmethanamine, 2-phenylethan-1-amine and 3-phenylpropan-1-amine favor to attack C2 of the intermediate to form 2-substituted pyridines. With the optimized geometries of the transition states, we found that the aromatic ring of the phenyl aliphatic amines may form cation-π interaction with the pyridinium of the intermediates, which could stabilize the transition states and facilitate the formation of 2-substituted pyridines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

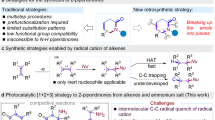

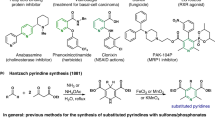

Pyridine and pyridone are important moieties in the structures of many drugs with a wide range of functions, such as loratadine (allergies), lansoprazole (ulcers), mirtazapine (depression), crizotinib (lung cancer), pioglitazone (diabetes), eszopiclone (insomnia), pirfenidone (ifibrosis), ciclopirox (antifungal), perampanel (epilepsy), arthpyrone (antiacetylcholinesterase) and ricinine (CNS stimulant) (Supporting Information, Figure S1). Especially, N-substituted 2-pyridone is a prevalent core structure in both natural products and chemical drugs1. Several synthetic approaches have been developed to construct N-substituted 2-pyridone derivatives2. In recent years, significant effort has been expended to develop synthetic strategies via alkyl migration or rearrangement reactions from O-substituted pyridines to N-substituted pyridones, such as C(sp3)-O bond cleavage3,4 and Claisen rearrangement5,6. Meanwhile, direct N-substitution of 2-pyridones has also been explored, despite the competing process existing between O and N alkylation7. Although these methods are undisputedly of importance to synthesize N-substituted 2-pyridones, they usually require expensive transition-metal catalysts, impractical substrates or display limited substrate scope (Fig. 1A1).

Our group previously discovered multiple N-substituted 3-arylisoquinolone derivatives as antitumor agents. These derivatives were prepared from O-substituted 3-arylisoquinolines via [2,3] or [3,3] rearrangement8. The conversion of acetal O-substituents to 2′-hydroxyl-1′-methoxylethyl N-substituents was promoted by dilute hydrochloric acid, which is distinct from the reported [2,3] rearrangements9. Herein we report a new approach to synthesize N-substituted 2-pyridones via an acid mediated rearrangement of 2-(2,2-dimethoxyethoxy) pyridines (Fig. 1B).

We detail the optimization of this procedure in addition to its substrate scope. In particular, aromatic and alkyl amines add to the 8-position of pyridinium derivatives 4 to give pyridone derivatives 5 (Fig. 1B), thereby providing a facile approach to prepare substituted amino compounds which have great potential, especially in drug discovery and development10. Alternatively, reaction with certain nucleophiles (e.g., phenylmethanamine, 2-phenylethan-1-amine and 3-phenylpropan-1-amine) was found to proceed via nucleophilic displacement at the C-2 position of the pyridinium ring to deliver 2-substituted pyridines 6 (Fig. 1B).

In addition, we isolated and characterized novel intermediates, namely, oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridinium salts (Fig. 1B). To the best of our knowledge, there are only two reports on the synthesis of oxazoline[3,2-a]quinolinium derivatives (Fig. 1A2); one is the synthesis of 1-bromomethyl-oxazoline[3,2-a]quinolinium bromides (2b) from N-allylquinolones via oxidation of the olefin by bromine and trapping via the quinolone O-atom11, the other is the synthesis of dihydrooxazolo[3,2-a]pyridinium methanesulfonate (2d) by the treatment of the hydroxyethyl pyridones with methanesulfonic anhydride and triethylamine in dichloromethane12. Furthermore, we found the nucleophilic reaction occurs primarily at the sp3-C (at the 8-position of compound 4, Fig. 1B) of the novel oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridinium derivatives, which differs from the familiar pyridine quaternary ammonium salt with the nucleophilic reaction commonly occurring at the α-position of the nitrogen of pyridinium ylide13.

Results and Discussion

Optimization of Reaction Conditions

Initially, the 2-(2,2-dimethoxyethoxy) pyridine (3a) was prepared from 2-halogenated pyridine by treatment with sodium 2,2-dimethoxyethanolate14. Subsequently we employed 3a as a test substrate to optimize the reaction conditions. After reacting with an acid, the solvent was evaporated and the residue was treated with a saturated sodium bicarbonate solution to provide N-substituted pyridone 5a (Table 1). Varying first the acid (Table 1, entries 1–9) revealed trifluoroacetic acid (Table 1, entry 9) as optimal.

Reducing the equivalents of trifluoroacetic acid was detrimental (Table 1, entries 10–12), therefore 3 equivalents was considered optimal. Similarly, reducing the reaction temperature to room temperature (Table 1, entry 13) was also detrimental. Finally, solvent screening (Table 1, entries 14–17) revealed toluene at 80 °C gave a somewhat improved yield (Table 1, entry 17). Furthermore, the reaction temperature could be reduced to 50 °C with no impact on yield (Table 1, entry 18). Therefore, we chose the conditions described entry 18 for further exploration.

Investigation of Different 2-(2,2-dimethoxyethoxy) Pyridines

Results shown in Fig. 2 demonstrate that a range of substituents, both electron donating and withdrawing, were tolerated on the pyridine moiety (5b–5k). Interestingly the 4- and 5-trifluoromethyl derivatives gave higher yields than the corresponding methyl derivatives, compared 5h to 5g and 5k to 5i. Quinolinyl and isoquinolinyl groups also worked smoothly, delivering products 5l, 5m and 5n in 89%, 84% and 63% yields, respectively. However, pyrazine and pyrimidine substrates failed to yield the desired products (5o and 5p) under the same conditions.

Oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridinium Structure Elucidation

As mentioned above, the residues from the reaction of 2-(2,2-dimethoxyethoxy) pyridines with acid were treated with saturated sodium bicarbonate solution to afford the 2′-hydroxyl-1′-methoxylethyl group N-substituted pyridones (5a-5n). In order to understand the reaction pathway, we purified intermediate, 4a, and elucidated its structure by 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR and mass spectrometry (Fig. 3). During the experiment, we found most of the intermediates were oils, except for the isoquinolinyl and quinolinyl derivatives that are solids. Therefore, in order to confirm the structure of the intermediate, we prepared isoquinolinyl compound 4n and quinolinyl compound 4l, both as solids, in good yields by reaction of requisite precursor 3 with hydrochloric acid in acetone. Finally, we chose 4l for crystallization and X-ray crystal structure determination (Fig. 3, details shown in Supporting Information). The results clearly show that the structure of the intermediate (4l) is the oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridinium species. Therefore, we conclude that the intermediates of the reaction are most likely the novel quaternary ammonium salts.

Proposed mechanism for the formation of intermediate oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridinium

Based on the isolation of oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridinium derivatives, we propose a reaction mechanism as shown in Fig. 4. Protonation of the acetal group of 3l followed by loss of methanol results in the formation of 8 which undergoes facile intramolecular cyclization to give 4l. Due to the conjugative effect of aromatic ring, the quaternary ammonium salt is relatively stable.

Investigation of nucleophile scope

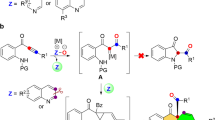

Encouraged by the novel structure and reactivity towards aqueous sodium bicarbonate to give 1-(2-hydroxy-1-methoxyethyl)pyridin-2(1 H)-ones (5a-5n), we were intrigued to investigate if the oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridinium derivatives would undergo reaction with other nucleophiles (Fig. 5).

It was found that the reaction was tolerant of a variety of nucleophiles. Anilines with electron donating and withdrawing groups gave good yields of the corresponding pyridones, whereas aromatic heterocyclic amines failed to yield any product (5A-H). Sodium phenolate gave a low yield (5I) whereas sodium thiophenolate (5J) gave a near quantitative yield, perhaps reflecting the matched reactivity with the soft electrophilic center. Alkyl amines (5K-N) also furnished products in good yields. Quinoline (5O) and iosquinoline (5P-Q) also served as good substrates, albeit with lower yields than the corresponding pyridyl derivatives. Surprisingly, phenylmethanamines were found to react at the 2-postion of the pyridine to yield 6A-F. Phenylmethanol and phenylmethanethiol failed to react, thus 6G and 6H were not observed. Similar to the phenylmethanamines, homologation to 2-phenylethan-1-amine or 3-phenylpropan-1-amine furnished only the 2-aminopyridine derivatives 6I and 6J respectively.

Taken together the results suggest that the nucleophilicity has a strong impact on the course of the reaction, e. g., weak nucleophiles such as phenylmethanol and phenylmethanethiol gave no products at all (6G, 6H) under these conditions. However, when the nucleophile is an aliphatic amine with aromatic substituent, such as phenylmethanamine, 2-phenylethan-1-amine and 3-phenylpropan-1-amine, formation of the N-substituted pyridones was not observed, and the reaction pathway shifted to produce 2-substituted pyridines. We postulated that the reason may involve pyridinium−π interaction (cation−π interaction) between the benzene ring and the pyridinium moiety. The proposed cation−π interaction is an intermolecular interaction which is different from the reported intramolecular cation−π interaction15.

Mechanistic Investigation by Quantum Chemistry Calculations

The above experimental results revealed a novel nucleophilic reaction with good regioselectivity to produce two different types of products. The reaction pathway was found to depend on the type of nucleophile used (Fig. 6). Accordingly, we proposed two possible reaction pathways and performed quantum chemistry (DFT) calculations for validation (Figs 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11).

The B3LYP/6-31 G(d) calculations revealed that the free energy barrier of aniline attacking the C8 of 4a to form transition state TSI2 is only 21.6 kcal/mol, which is much lower than the barrier needed for the aniline to attack the C2 of 4a (54.6 kcal/mol), indicating that the nucleophilic reaction favors the former pathway to a large extent to form 5A. Furthermore, IC is more stable than IB by about 2.0 kcal/mol, demonstrating that ID (5A) should be the final product of the reaction between 4a and IA (Fig. 7).

Calculations showed that the transition state of methylamine interacting with 4a is similar to that of aniline. When methylamine attacks C8 of 4a, the calculated free energy barrier to transition state TSII2 is only 16.6 kcal/mol, which is much lower than that of attacking C2 of 4a (46.3 kcal/mol for transition state TSII1). Thus, IID (5K) should be the final product of the reaction between 4a and methylamine (Fig. 8).

However, calculations demonstrated that the free energy barrier of attack at C2 of 4a by phenylmethanamine to form intermediate IIIC via transition state TSIII2 is 17.3 kcal/mol, which is lower than that of the transition state (TSIII1) by 9 kcal/mol. As shown in Fig. 9, the trifluoroacetate anion then interacts with IIIC to afford the product IIID (6A) which has been proven by experiment. Moreover, the free energy barrier of formation TSIII1 (26.3 kcal/mol) is closed to that of TSI2 (21.6 kcal/mol, Fig. 7). But the free energy barrier of formation TSIII2 (17.3 kcal/mol) is much lower than that of TSI1 (54.6 kcal/mol, Fig. 7), and which is also lower than that of TSIII1. Therefore, the calculation results also demonstrated that phenylmethanamine nucleophile preferred to attack the C2 of 4a but aniline favors the C8 of 4a.

Similarly, when 6I and 6J attack C2 of 4a, the calculated free energy barriers are 13.3 and 14.3 kcal/mol, respectively. In contrast, the energy of attacking C8 of 4a by 6I and 6J are much higher (31.1 and 27.0 kcal/mol). As shown in Figs 10 and 11, the benzene ring and the pyridinium are almost parallel to each other, indicating the effect of pyridinium−π interaction (cation−π interaction)15 between them, which may contribute to reduce the free energy barrier of transition state.

Therefore, it could be concluded that the regioselectivity observed in this study could be interpreted by the calculated free energy barriers of forming various transition state structures at the first step from 4a with different nucleophiles.

Conclusion

We have discovered a novel approach to prepare the prevalent heterocyclic structures of N-substituted pyridones and 2-substituted pyridines from 2-(2,2-dimethoxyethoxy)-pyridines via regioselectively metal-free C-O and C-N bond-cleaving of novel intermediate oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridiniums. We have shown that this intermediate can undergo nucleophilic addition with anilines, alkylamines, phenol sodium and thiophenol sodium to afford N-substituted pyridones, while the phenylalkylamines gave 2-substituted pyridines. Furthermore, we proposed two different mechanisms to interpret the nucleophile-dependent regioselectivity of the reactions, which have been validated by quantum chemistry calculations at B3LYP/6-31 G(d) level. Interestingly, we found that the intermolecular cation−π interaction between the benzene ring and the pyridinium moiety should contribute to the regioselective formation of the 2-amino substituted pyridines. In particular, the sp3-C amination of the oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridinium moiety with aromatic amines and alkylamines to afford N-substituted pyridones may have great application in drug development. Further study to explore the potential application of the novel quaternary ammonium moiety is undergoing in our laboratory.

Methods

General procedure for synthesis of oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridinium (4)

2-(2,2-dimethoxyethoxy) pyridine 3 (1 mmol) was dissolved in toluene (5 ml) and the acid (3 mmol) was added to this mixture under stirring. The temperature was warmed to 50 °C. After reaction for hours, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and the solvent was evaporated. The residue was washed by petroleum ether and dried under vacuum to give the oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridinium 4.

General procedure for preparing N-substituted pyridone (5)

2-(2,2-dimethoxyethoxy) pyridine 3 (1 mmol) was dissolved in toluene (5 ml) and the acid (3 mmol) was added to this mixture under stirring. The temperature was then warmed to 50 °C. After reaction for hours, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and the saturated sodium bicarbonate solution was added. After stirring for another two hours, the solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified through silica gel chromatography to give the N-substituted pyridone 5.

General procedure for synthesis of N-substituted pyridine 5 or O-substituted pyridine (6)

2-(2,2-dimethoxyethoxy) pyridine 3 (1 mmol) was dissolved in toluene (5 ml) and the trifluoroacetic acid (3 mmol) was added to this mixture under stirring. The temperature was warmed to 50 °C. After reaction for hours, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and the solvent was evaporated. The residue was dispersed in toluene (5 ml), and then the amine (3 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Then after evaporating the solvent, the residue was purified through silica gel to give the product 5 or 6, respectively.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, B. et al. Regioselectivity and Mechanism of Synthesizing N-Substituted 2-Pyridones and 2-Substituted Pyridines via Metal-Free C-O and C-N Bond-Cleaving of Oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridiniums. Sci. Rep. 7, 41287; doi: 10.1038/srep41287 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Cuboni, S. et al. Loratadine and analogues: discovery and preliminary structure-activity relationship of inhibitors of the amino acid transporter B(0)AT2. J. Med. Chem. 57, 9473–9479 (2014).

Li, C., Kähny, M. & Breit, B. Rhodium-catalyzed chemo-, regio-, and enantioselective addition of 2-pyridones to terminal allenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 13780–13784 (2014).

Pan, S., Ryu, N. & Shibata, T. Ir(I)-catalyzed synthesis of N-substituted pyridones from 2-alkoxypyridines via C-O bond cleavage. Org. Lett. 15, 1902–1905 (2013).

Yeung, C. S., Hsieh, T. H. H. & Dong, V. M. Rapid antioxidant capacity screening in herbal extracts using a simple flow injection-spectrophotometric system. Chem. Sci. 2, 544–548 (2011).

Rodrigues, A., Lee, E. E. & Batey, R. A. Enantioselective palladium(II)-catalyzed formal [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of 2-allyloxypyridines and related heterocycles. Org. Lett. 12, 260–263 (2010).

Itami, K., Yamazaki, D. & Yoshida, J. Palladium-catalyzed rearrangement/arylation of 2-allyloxypyridine leading to the synthesis of N-substituted 2-pyridones. Org. Lett. 5, 2161–2164 (2003).

Zhang, X., Yang, Z. P., Huang, L. & You, S. L. Highly regio- and enantioselective synthesis of N-substituted 2-pyridones: iridium-catalyzed intermolecular asymmetric allylic amination. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 54, 1873–1876 (2015).

Li, B. et al. Discovery of N-substituted 3-arylisoquinolone derivatives as antitumor agents originating from O-substituted 3-arylisoquinolines via [2,3] or [3,3] rearrangement. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 77, 204–210 (2014).

West, T. H., Daniels, D. S., Slawin, A. M. & Smith, A. D. An isothiourea-catalyzed asymmetric [2,3]-rearrangement of allylic ammonium ylides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4476–4479 (2014).

Paradine, S. M. et al. A manganese catalyst for highly reactive yet chemoselective intramolecular C(sp(3))-H amination. Nat. Chem. 7, 987–994 (2015).

Ukrainets, I. V., Mospanova, E. V., Davidenko, A. A. & Shishkina, S. V. 4-hydroxy-2-quinolones synthesis, chemical reactions, and analgesic activity of 1-allyl-4-hydroxy-6,7-dimethoxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid alkylamides. Chem Heterocycl Com. 46, 1084–1095 (2010).

Harrington, J. M. et al. Synthesis and Iron Sequestration Equilibria of Novel Exocyclic 3-Hydroxy-2-pyridinone Donor Group Siderophore Mimics. Inorg. Chem. 49, 8208–8221 (2010).

Auth, J., Padevet, J., Mauleón, P. & Pfaltz, A. Pyridylidene-Mediated Dihydrogen Activation Coupled with Catalytic Imine Reduction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 54, 9542–9545 (2015).

Saitton S., Kihlbergb, J. & Luthman, K. A synthetic approach to 2,3,4-substituted pyridines useful as scaffolds for tripeptidomimetics. Tetrahedron, 60, 6113–6120 (2004).

Yamada, S., Yamamoto, N. & Takamori, E. A Molecular Seesaw Balance: Evaluation of Solvent and Counteranion Effects on Pyridinium−π Interactions. Org. Lett. 17, 4862–4865 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation (81273435, 81302699 and 81573350), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai, China (14ZR1447800), The State Key Laboratory of Natural and Biomimetic Drugs (K20150205).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z., B.Z. and J.S. contributed to the experimental design and the manuscript revision.B.L., S.X., Y.Y. and J.F. contributed equally to the main experiments of this work. Specifically, B.L. contributed to the experimental design, synthesis and the manuscript writing. S.X. contributed to the methodology optimization and the derivatives synthesis. Y.Y. contributed to the quantum chemistry calculations. J.F. contributed to the derivatives synthesis and the X-ray analysis. For the other contributed authors, P.L., Y.Z., J.Z. and Z.X. contributed to the discussion of the experiment frequently and advice for the writing of the manuscript. A.H. contributed to the mechanism interpretation and manuscript revision..

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, B., Xue, S., Yang, Y. et al. Regioselectivity and Mechanism of Synthesizing N-Substituted 2-Pyridones and 2-Substituted Pyridines via Metal-Free C-O and C-N Bond-Cleaving of Oxazoline[3,2-a]pyridiniums. Sci Rep 7, 41287 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41287

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41287

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.