Abstract

In most human sporadic prion diseases the phenotype is consistently associated with specific pairings of the genotype at codon 129 of the prion protein gene and conformational properties of the scrapie PrP (PrPSc) grossly identified types 1 and 2. This association suggests that the 129 genotype favours the selection of a distinct strain that in turn determines the phenotype. However, this mechanism cannot play a role in the phenotype determination of sporadic fatal insomnia (sFI) and a subtype of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) identified as sCJDMM2, which share 129 MM genotype and PrPSc type 2 but are associated with quite distinct phenotypes. Our detailed comparative study of the PrPSc conformers has revealed major differences between the two diseases, which preferentially involve the PrPSc component that is sensitive to digestion with proteases (senPrPSc) and to a lesser extent the resistant component (resPrPSc). We conclude that these variations are consistent with two distinct strains in sFI and sCJDMM2, and that the rarer sFI is the result of a variant strain selection pathway that might be favoured by a different brain site of initial PrPSc formation in the two diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is now well established that the basic mechanism of prion diseases relies on the conversion of the normal or cellular prion protein (PrPC) to the abnormal and infectious conformer commonly identified scrapie PrP (PrPSc)1. A challenging aspect of this conversion mechanism is that it leads to the formation of heterogeneous PrPSc species commonly identified as strains2. Historically, strains have been defined as prion species that upon transmission to receptive hosts are associated with different disease phenotypes as determined by distinct incubation periods, histological lesions and PrP deposits with respect to type and topography3. Subsequently, strains were correlated to PrPSc species exhibiting distinct physicochemical properties, such as electrophoretic mobility, which were attributable to different conformations linked to any primary to quaternary structure variation4,5,6,7,8.

Human prion diseases are characterized by a marked phenotypic heterogeneity that has hampered their recognition and understanding9. Although this heterogeneity is due in part to the unique presence of three etiologies – sporadic, inherited and acquired by infection – the sporadic group alone includes at least seven phenotypes2,10. We proposed a classification of sporadic human prion diseases based on the pairing of the patient’s genotype at codon 129 of the PrP gene (the site of a common methionine (M)/valine (V) polymorphism) with the type, 1 or 2, of PrPSc (as determined by electrophoretic mobility of the protease resistant PrPSc core or resPrPSc)11,12. Individual 129 genotype - PrPSc type pairs consistently correlate and identify most sporadic prion disease phenotypes2,10,12. For example, sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) affecting 129MM patients and associated with PrPSc type 1 (identified as sCJDMM1) exhibits a clinical and pathological phenotype that significantly differs from the phenotypes associated with sCJDVV1 or sCJDMM212. However, this principle does not apply to all sporadic prion diseases.

Sporadic fatal insomnia (sFI, also identified as sCJDMM2T, for thalamic form), and sCJDMM2 (also identified as sCJDMM2C, for cortical form) are both associated with the 129MM genotype and PrPSc conformers of type 2, which display a similar resPrPSc profile in both diseases upon standard electrophoretic analysis. However, in spite of sharing molecular features, sFI and sCJDMM2 are associated with strikingly different clinical and histopathological phenotypes as well as prevalences (Supplementary Table S1). In sFI the major lesions are concentrated to the thalamus and consist of severe loss of neurons; in contrast, sCJDMM2 is characterized by severe spongiform degeneration made of distinctive large vacuoles that preferentially affect the cerebral cortex10,12. Bioassay studies indicate that the two diseases are associated with distinct prion strains13. Detailed studies of resPrPSc have shown consistent differences which, however, involve very minor fragments, raising questions as of whether these minor variations can bring about such drastic phenotypic differences14,15. Furthermore, systematic comparative studies of the physicochemical characteristics of the PrPSc associated with the two diseases are missing.

We searched for variations of PrPSc properties that could explain the striking phenotypic heterogeneity of sFI and sCJDMM2. We found major variations in the protease-sensitive component of PrPSc, while novel although less striking differences also emerged in resPrPSc.

Results

Glycoform ratios and electrophoretic patterns of totPrPSc and resPrPSc

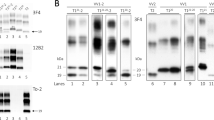

Comparative examination on Western blots (WB) of resPrPSc obtained from frontal cortex and enriched by sodium phosphotungstate (NaPTA) precipitation confirmed the lack of qualitative differences between sFI and sCJDMM2 electrophoretic profiles with regard to mobility and ratios of the three resPrPSc glycoforms (Fig. 1A,D).

BH from sCJDMM2 and sFI were precipitated with NaPTA, and the totPrPSc-containing pellets were either PK-treated (PK 10 U/ml) generating resPrPSc (A) or left untreated (totPrPSc) (B). The percent distribution of the glycoforms of resPrPSc and totPrPSc harvested from NaPTA precipitates are shown in the bar graphs (D,E). (A,B,D,E) Unlike resPrPSc, totPrPSc shows WB profiles that differ in the two diseases because of a significant over-representation of the di-glycosylated form in sFI. In (A), a non-specific band of ~32 kDa is also observed (arrow). Following NaPTA precipitation, the supernatants were precipitated in methanol and resuspended in sample buffer. (C,F) Supernatants from sCJDMM2 and sFI, run on the same gel but not in adjacent lanes, show similar ~27–37 kDa WB profiles and percent distribution of the glycoforms of “PrPC” (P > 0.05, Student’s t-test). In sFI, the “PrPC” glycoform ratio is significantly different from that of totPrPSc (B,E), indicating that the totPrPSc ratio is not due to contamination with “PrPC”. (Labels on the right side of each WB indicate the three PrP glycoforms: D: Di-glycosylated; M: Mono-glycosylated; U: Un-glycosylated. Tissue samples from four cases of sCJDMM2 and sFI, respectively, and the mAb to PrP, 3F4, have been used in all figures, unless otherwise indicated).

However, differences were demonstrated when the proteinase K (PK) treatment of enriched samples was omitted, allowing for the examination of total PrPSc (totPrPSc) [i.e. resPrPSc + PK-sensitive PrPSc (senPrPSc) = totPrPSc]. Total PrPSc revealed a significant variation in the ratios of the di-glycosylated, mono-glycosylated and un-glycosylated conformers that respectively showed the 56:28:16 ratios in sFI and 21:40:39 in sCJDMM2 (Fig. 1B,E). The possibility that the different glycoform ratios of totPrPSc reflected significant contamination of the NaPTA precipitate with PrPC was considered to be very unlikely in view of the different glycoform ratios exhibited by the PrP (presumably PrPC) recovered in the NaPTA supernatant (Fig. 1C,F). Similar results were obtained from the medial thalamus, the cerebral region most affected in sFI (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Further characterization of totPrPSc and resPrPSc on two-dimensional (2-D) WB demonstrated marked differences in totPrPSc harvested from sFI and sCJDMM2 with regard to the number and gel mobility of the electrophoretic spots (Fig. 2A). With regard to totPrPSc, the 2-D polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) pattern was relatively simple in sFI, but quite complex in sCJDMM2, as it included PrPSc isoforms with wide ranges of relative molecular weights and isoelectric points. This disparity was especially prominent in the 6.0–7.0 isoelectric points (pI) range. In this region of the sCJDMM2 preparations, the spots corresponding to the three glycoforms were blurred by a smear comprised in the 40–20 kiloDalton (kDa) range. Furthermore, a prominent cluster of spots could be seen in the 19 kDa region while a weak but large, blurred spot occupied the ~50 kDa high molecular weight (h.m.w.) area. Besides seemingly confirming the ratios of the three totPrPSc glycoforms observed in one-dimensional (1-D) WB, differences in pI were uncovered in the two diseases, due to the spanning over a wider range of pI for glycoforms of sCJDMM2 totPrPSc. Following PK treatment, the sCJDMM2 electrophoretic pattern became much simpler, matching that of sFI (Fig. 2B). In both diseases, resPrPSc spots conspicuously shifted toward the acidic region compared to those of totPrPSc. Patterns were even further simplified and variations between sCJDMM2 and sFI further reduced after deglycosylation of totPrPSc and resPrPSc with PNGase F, although minor differences persisted (Fig. 2C,D). Altogether, these 2-D WB findings confirm that the major heterogeneity between sFI and sCJDMM2 PrPSc, especially with respect to the ratios and pI of the glycoforms, is related to the totPrPSc species, pointing to senPrPSc as the component accountable for the diversity.

TotPrPSc (A), resPrPSc (B), PNGase F-deglycosylated totPrPSc (C) and deglycosylated resPrPSc (D) were processed for 2-D WB following BH precipitation with NaPTA in sFI and sCJDMM2 as indicated. (A) TotPrPSc shows a much more complex spot pattern in sCJDMM2 than in sFI, the pattern of which resembles that of PrPC 17. The patterns become much simpler and similar in the two diseases following treatment with PK (B), PNGase F (C) or both treatments combined (D). (Labels on the side of each WB indicate the three PrP glycoforms: D: Di-glycosylated; M: Mono-glycosylated; U: Un-glycosylated; PK 10 U/ml).

Characterization of full-length totPrPSc

To further investigate the complexity of the totPrPSc in sCJDMM2, we immunoprecipitated the full-length component of totPrPSc from NaPTA preparations using a monoclonal antibody (mAb) to the PrP N-terminal region (Fig. 3). The 1-D WB of the immunoprecipitate showed that the three full-length PrPSc glycoforms associated with sFI and sCJDMM2 reproduced the ratios previously observed on preparations of whole totPrPSc (Figs 3A and 1B,E). In addition, the eluate demonstrated the presence of two large h.m.w. bands of ~53 kDa and ~90 kDa in sCJDMM2 while a single, less well represented ~53 kDa band was detectable in sFI (Fig. 3A). On 2-D WB, the two ~53 kDa and ~90 kDa h.m.w. components were very prominent in sCJDMM2 preparations, where they occupied a large area of the blot at approximately pI 6.5, while the ~53 kDa component alone was barely noticeable in sFI (Fig. 3B). Presence, relative quantity and PrPSc nature of the ~53 kDa h.m.w. were confirmed following immunoprecipitation (IP) or in NaPTA preparations (i.e. omitting IP), using different elution conditions to exclude co-elution of the capturing mAb, and by probing with polyclonal antibodies to the C- and N-termini as well as with the conformational mAb OCD4 (Supplementary Figs S2 and S4B)16. The ~53 kDa and ~90 kDa h.m.w. components were found to be glycosylated and partially PK-sensitive; the ~53 kDa form was estimated to be 3–4 times better represented in sCJDMM2 than in sFI (Supplementary Fig. S2F–I).

Immunoprecipitation was carried out on NaPTA pellets with the mAb 8B4 to PrP N-terminus. (A) The 1-D WB shows h.m.w. bands (arrows) especially prominent in sCJDMM2 preparations, in addition to the three typical PrPSc glycoforms; (B) In 2-D WB, spots corresponding to the h.m.w. are dramatically represented in sCJDMM2 and barely detectable in sFI (arrows). Note that in these full-length totPrPSc preparations, low molecular weight fragments are lacking but the glycoform ratios reproduce those of the whole totPrPSc (Fig. 2A).

When the 2-D WB patterns of whole and full-length totPrPSc from sCJDMM2 were compared, the pattern of the full-length totPrPSc isoform (presence of the ~53 kDa and ~90 kDa spots notwithstanding) appeared much simpler than that of the whole totPrPSc (which also comprised the truncated forms), especially in the pI region where the two h.m.w. components were located (Figs 2A and 3B). In contrast to those of sCJDMM2, totPrPSc 2-D patterns obtained from sFI were comparable, regardless of whether they exclusively represented the full-length totPrPSc isoform or the whole totPrPSc comprising full-length and truncated forms (Figs 2A and 3B). In conclusion, the 2-D study of full-length totPrPSc (i) confirms the presence in sCJDMM2 totPrPSc of significant amounts of ~53 kDa and ~90 kDa h.m.w. species, which appear to contain full-length totPrPSc; (ii) indicates that the PrPSc fragments that complicate the WB 2-D pattern of totPrPSc in sCJDMM2 originate from the h.m.w. components (Figs 2A and 3B); and (iii) confirms the variations of glycoform ratios and pI in sCJDMM2 and sFI, which are especially noticeable in the full-length un-glycosylated component (Fig. 3B).

Sedimentation properties of prion aggregates

PrPSc variations distinguishing sCJDMM2 and sFI were further searched with sedimentation equilibrium (SE) and sedimentation velocity (SV) centrifugations, which are commonly used to explore density and size of the PrPSc aggregates, respectively. Following SE, totPrPSc sedimentation profiles clearly differed between the two diseases: in sCJDMM2, over 70% of totPrPSc aggregates populated the sucrose high-density region of the gradient (bottom fractions), while in sFI, over 80% of the totPrPSc was recovered in a distinct peak located in a lower density region (fractions 3–8) (Fig. 4A). Remarkably, unlike those of sCJDMM2, sFI glycoform ratios varied significantly along the gradient (Supplementary Fig. S3). This variation resulted in a significant difference between the glycoform ratios recovered in the low- and high-density fractions in sFI, and in a difference in ratios between the two diseases in the low- but not in the high-density fractions (Supplementary Fig. S3B).

TotPrPSc from sCJDMM2 and sFI were centrifuged at high speed for 19 hours in a 10–60% sucrose gradient. Identical volumes were collected from each fraction and processed for WB. Sedimentation profiles of totPrPSc (A) and resPrPSc (B). Note the distinct peak of totPrPSc low-density aggregates in sFI and the prevalence of high-density aggregates in totPrPSc from sCJDMM2 (A). In contrast, only high-density aggregates are demonstrated in resPrPSc (B). (PK 10 U/ml).

Following PK digestion of individual SE fractions, the signal of fractions 3–8 pertaining to sFI was no longer detectable, while the only sizable quantity of resPrPSc aggregates populated the high-density fractions in both diseases (Fig. 4B). Thus, PK treatment removed all significant differences between the two gradient profiles although minor differences remained in the glycoform ratios (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. S5). In contrast, when PK digestion was carried out on the whole totPrPSc preparations before SE (rather than on the individual SE fractions), two distinct although overlapping aggregate populations were observed that involved fractions of lower density (fractions 8–18) in sFI than in sCJDMM2 (12–21) (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Experiments on control cases indicated that totPrPSc recovered in P2 from sFI and sCJDMM2 and used for SE might have been contaminated up to 16% by PrPC, insoluble PrP (iPrP)17, or both (Cracco et al., unpublished data). Therefore, SE was repeated using totPrPSc P2 preparations generated under stringent conditions (indicated as stSE, see Supplementary Materials and Methods) and harvested from sCJDMM2 and sFI as well as from brains free of neurological diseases. Although following stSE the majority of sCJDMM2 and sFI totPrPSc aggregates populated the high-density region of the gradient, smaller but still significant differences in their respective distributions were also detected in the low-density area of the gradient: in sCJDMM2, only 4% of totPrPSc was recovered in fractions 5–10, whereas in sFI this component exceeded 14% (P < 0.05); a significant difference was also found in the high-density regions of the gradient (fractions 17–21, P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A). WB of stSE fractions 6–8 combined, which were harvested from brain equivalents of negative controls (presumably comprising PrPC, iPrP or both) as well as from sFI and sCJDMM2, indicated that the contribution of PrPC or iPrP (lane 1) was insignificant, excluding the possibility that the low-density peaks in sFI and sCJDMM2 (lanes 2, 3) were due to contamination (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, major SE characteristics of low- and high-density fractions (6–8 and 17–21), like PK sensitivity and variations of glycoform ratios observed along the gradient, were reproduced in stSE, indicating that totPrPSc exhibited similar qualitative features in SE and stSE gradients (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Fig. S3, and Cracco et al., unpublished data). It should also be noted that the stSE procedure caused a significant loss of totPrPSc to the S2 fractions, which impacted preferentially sFI and may explain the quantitative variations in aggregate distribution between the two SE methods (Cracco et al., unpublished data).

Total PrPSc was harvested under stringent conditions from identical BH volumes of sCJDMM2 and sFI, while PrP, likely iPrP, was similarly obtained from cases free of neurological diseases used as controls. Both preparations were centrifuged at high speed for 19 hours in a 10–60% sucrose gradient. (A) Sedimentation profiles of totPrPSc in sCJDMM2 and sFI showing a slight prevalence of low-density aggregates in sFI and high-density aggregates in sCJDMM2. (B) WB of fractions 6–8 combined, from controls, sFI and sCJDMM2 (lanes 1, 2, 3, respectively), harvested from the same brain equivalents, excludes the possibility that the low-density peaks in sFI and sCJDMM2 (lanes 2, 3) are populated by iPrP only17 (lane 1). (C) Fractions 6–8, normalized to the same total protein concentration and exposed to limited proteolysis (PK 0.031 U/ml), are PK-sensitive in both diseases and display the same difference in glycoform representation as in non-stSE conditions (Supplementary Fig. S3).

The possibility that in SE the low-density peak observed in sFI reflected contamination of totPrPSc with PrPC or iPrP (expected to populate similar gradient fractions and to be PK-sensitive) seemed also unlikely in view of the results of the IP experiments with mAb OCD4, the conformational antibody reacting with misfolded PrP species but not with PrPC 16. Immunoprecipitation of PrP from the 4–8 and 17–21 SE fractions obtained from sFI and sCJDMM2 yielded significant quantities of PrP displaying glycoform ratios similar to those of the totPrPSc directly collected from the same SE and stSE fractions (Supplementary Figs S3 and S4). In contrast, OCD4 captured relatively negligible amounts of PrP, possibly iPrP, in S1 and S2 fractions generated from a negative case (Supplementary Fig. S4)17. Of note, h.m.w. components populated both low- and high-density fractions in sCJDMM2 but only the high-density fractions in sFI (Supplementary Fig. S4B).

Following SV centrifugation (1 hr, in 5–15% sucrose gradient), the sedimentation profiles were again different in the two diseases (Fig. 6). In sFI, virtually all totPrPSc aggregates were confined to the low-density fractions (fractions 1–5), while in sCJDMM2 only approximately 10% of totPrPSc distributed in that region, while nearly 70% was recovered in the highest density fractions of the gradient (Fig. 6A). Treatment with PK equalized the profiles since aggregates were exclusively recovered in the highest density fraction in both diseases, further adding to the notion that most PrPSc disparity resides in the senPrPSc fraction (Fig. 6B).

TotPrPSc from sCJDMM2 and sFI cases were subjected to 1 hour of high-speed centrifugation in a 5–15% sucrose gradient. Individual fractions were processed for WB untreated (A) or following PK treatment (10 U/ml) (B). (A) TotPrPSc aggregates preferentially populate low-density fractions in sFI and the highest density fraction in sCJDMM2. (B) No significant difference is found between the profiles generated by resPrPSc in the two diseases.

Solubility properties of totPrPSc and resPrPSc

Finally, both totPrPSc and resPrPSc associated with sCJDMM2 and sFI were further characterized by the conformational solubility and stability assay (CSSA) that assesses conformational stability based on the rate of PrPSc solubilisation at increasing concentrations of guanidine hydrochloride (GdnHCl)18,19. In sCJDMM2, totPrPSc and resPrPSc showed comparable solubility values; in sFI, while the totPrPSc solubility roughly matched that of sCJDMM2, resPrPSc was significantly less soluble than totPrPSc as well as the resPrPSc of sCJDMM2 (Fig. 7). Therefore, conformational stability is another feature differentiating resPrPSc in sFI and sCJDMM2.

[GdnHCl]1/2 represents amounts (in molar values) required to solubilize half of the substrate and is used as an indication of conformational stability. The mean [GdnHCl]1/2 values for totPrPSc and resPrPSc are 1.54 M and 1.38 M in sCJDMM2, and 1.40 M and 1.71 M in sFI. Although the stability values of totPrPSc are comparable in the two diseases, the stability of resPrPSc in sFI is significantly higher than that of the corresponding totPrPSc as well as that of resPrPSc associated with sCJDMM2.

Discussion

We have uncovered significant variations affecting totPrPSc and, to a lesser extent, resPrPSc conformers that distinguish sFI and sCJDMM2. The variations appear to affect primarily the senPrPSc component of totPrPSc, as they drastically diminish when the totPrPSc preparations are digested with PK to reveal resPrPSc. The variations of totPrPSc involve a variety of properties, including (i) ratio and isoelectric point of the glycoforms, (ii) presence of two ~53 kDa and ~90 kDa h.m.w. prominent components and a plethora of low m.w. PrPSc fragments as well as (iii) existence of an aggregate population displaying distinct density and, possibly, size (Supplementary Table S2). The variations affecting primarily resPrPSc comprise (i) distinct densities of aggregates, which are detected when PK treatment is carried out before (rather than after) SE fractionation, and (ii) conformational stability (Supplementary Table S2). Furthermore, lower PK resistance of totPrPSc in sFI compared to that of sCJDMM2 has been reported by Saverioni et al.20. The finding that totPrPSc diversity in the two diseases appears to be mostly determined by the senPrPSc component may explain the enduring lack of recognition of significant PrPSc heterogeneity in these two diseases.

The observation that in sFI (but not in sCJDMM2) the glycoform ratio of totPrPSc is dominated by the di-glycosylated form and differs from that of resPrPSc argues that, in sFI, senPrPSc and resPrPSc preferentially target different PrPC glycoforms for conversion21,22,23,24,25. It has recently been proposed that the sialic acid moiety of the PrPC glycans impairs conversion to PrPSc 24. Therefore, the dominance of the di-glycosylated (thus highly sialylated) isoform in sFI totPrPSc, presumably involving the senPrPSc component, might reflect a lower sialylation (or other variations) of PrPC glycans available for conversion to senPrPSc in sFI, allowing for the conversion of even the PrPC di-glycosylated isoform. Alternatively, PrPC conversion to senPrPSc might be less affected by sugar sialylation in sFI, or senPrPSc and resPrPSc glycoforms might have different turnovers. Regardless of the mechanism, the difference in glycoform ratios is significant considering the rising evidence that glycan representation, structure or both can affect strain characteristics21,25,26.

The high representation of the ~53 kDa and ~90 kDa h.m.w., and of the low molecular weight (l.m.w.) components in totPrPSc from sCJDMM2 only, strikingly demonstrated in 2-D WB of totPrPSc, is puzzling. Our preliminary characterization indicates that the two components share several physicochemical features, suggesting that l.m.w. fragments derive from the h.m.w. component. Immunoprecipitation experiments and probing with a number of PrP antibodies indicate that the ~53 kDa h.m.w. component contains glycosylated, full-length PrP and may represent PrP dimers (the ~90 kDa would consist of trimers) or aggregates that are covalently linked. Most of the h.m.w. and l.m.w. components appear to be insoluble in detergents and, at least in part, PK-sensitive, suggesting that they mostly comprise senPrPSc. High m.w. PrP components, similar to the ~53 kDa we observed in sCJDMM2, have been reported previously18,20,27,28,29. Priola and colleagues28 originally described a 60 kDa PrP, covalently-linked dimer in neuroblastoma cells expressing hamster PrP and in scrapie-infected hamster brains. A PrPSc dimer has also been observed in a variety of conditions including infected and non-infected transgenic mice expressing mutant PrP, detergent-insoluble preparations from sCJDMM2 brain homogenates and from bank voles inoculated with the aforementioned brain homogenate, but not bank vole normal brains18,20,29. Remarkably, the dimer presence in totPrPSc of sCJDMM2-inoculated bank voles implies that the dimer is transmissible and therefore is an intrinsic characteristic of the sCJDMM2 strain.

Furthermore, the 2-D experiments also confirmed the distinct glycoform ratios observed in 1-D WB and uncovered the difference in pI of the glycoforms associated with totPrPSc and resPrPSc in sCJDMM2 and sFI. Somewhat similar patterns were observed in a previous 2-D WB comparative study of full-length totPrPSc in sFI and sCJDMM214,30. These studies, however, did not report the presence of h.m.w. electrophoretic spots perhaps due to methodological differences14,30.

The disparity of senPrPSc aggregates that we observed between sFI and sCJDMM2, following fractionation by long and short sucrose density centrifugations, is also noteworthy since it relates to the current notion that aggregate profiles are good identifiers of distinct strains31. The long (19 hrs.) SE centrifugations, thought to primarily assess density (mass/volume), showed that most totPrPSc co-distributes with low-density aggregates in sFI and with aggregates of high density in sCJDMM2. However, the detergent insoluble fractions used in this SE protocol included up to 16% contamination with non-PrPSc (PrPC and insoluble PrP). A more stringent SE protocol still demonstrated a significant difference between the distribution of sCJDMM2 and sFI low-density aggregates, although this protocol led to a loss of totPrPSc that predominantly affected senPrPSc in sFI. Furthermore, the dominant presence of senPrPSc in the sFI low-density fractions was further supported by the distinct glycoform ratios and by the immunoreactivity of the PrP recovered in these fractions using a conformational antibody that recognizes totPrPSc and resPrPSc but not PrPC. Although further study is needed, an appealing possibility is that the sFI low-density aggregates match the protease-sensitive small oligomers recently described and are associated with detergent-insoluble cholesterol-rich lipids originating from the PrPSc association with membrane rafts32. Furthermore, association with lipids is thought to play a role in maintaining PrPSc conformation and controlling strain features33,34,35,36. Notably, the sFI (but not the sCJDMM2) glycoform ratios changed significantly along the gradient, regardless of the type of SE used, implying that in sFI the low- and high-density aggregates are composed of monomers that differ with respect to glycosylation. A further distinctive feature is that the h.m.w. components appeared to populate both low- and high-density fractions in sCJDMM2 but only the high-density fractions in sFI. Although caution has to be exercised because of the different representation of the h.m.w. components in the two diseases, this finding suggests that, in addition to representation, h.m.w. components differ also with respect to their participation in aggregate formation in sFI and sCJDMM2. Protease treatment of the individual fractions removed all differences between sFI and sCJDMM2, indicating that all low-density fractions 1–10 harboured senPrPSc while resPrPSc populated mostly the high-density fractions 11–21, in amounts directly related to the density of the fractions. However, when PK digestion of totPrPSc was carried out before SE fractionation (rather than on the individual fractions), two distinct, though overlapping, aggregate populations were observed in sFI and sCJDMM2, which accounted for over 80% of the entire resPrPSc aggregates in both conditions. The different resPrPSc aggregate distribution under this PK treatment condition likely denotes partial re-aggregation of resPrPSc that results in distinct aggregate populations in the two diseases. It also underlines the importance of the timing of PK treatment in SE31.

Sedimentation velocity, which is supposed to separate aggregates by size, showed, like SE, that the great majority of totPrPSc aggregates populated the light fractions in sFI, while in sCJDMM2 the majority was recovered in the fractions of highest density. This sedimentation procedure generated an almost symmetrical bimodal profile due to the nearly complete separation of light fractions (1–5 in decreasing representation) from the 20–21 heavy fractions, suggesting that in our SV conditions aggregates appear similar in size in both diseases but are differently represented, with the smaller aggregates predominating in sFI. Following protease treatment of the individual fractions, aggregates were almost exclusively recovered in the densest fractions. However, in view of its minimalist bimodal profile, our SV procedure might have failed to fully separate aggregates in sFI and sCJDMM2, making the interpretation of the sedimentation profile challenging. Nonetheless, SV experiments further confirm the dissimilarity of totPrPSc aggregates in sFI and sCJDMM2.

Sedimentation velocity studies of PrPSc have recently been carried out in sCJD subtypes by Saverioni et al.20. The SV profiles of sCJDMM2 and sFI in this study profoundly differ from ours especially due to the underrepresentation of the low-density component in sFI. However, Saverioni et al.20 carried out SV fractionation on PrPSc preparations (P3) which were purified under stringent conditions by performing two rounds of over 2-hour high speed centrifugations, and sonication. Nonetheless, a significant difference in aggregate distribution was observed between sFI and sCJDMM220.

The major finding obtained with the conformational solubility and stability assay was that while the stabilities of totPrPSc were similar in both diseases, the resPrPSc stability was significantly higher in sFI not only when compared with that of the corresponding totPrPSc but also with respect to the stability of resPrPSc in sCJDMM2. A possible mechanism of the enhanced stability of sFI PrPSc following PK treatment is re-aggregation of resPrPSc promoted by PK treatment, which is different in the two diseases and results in increased stability of resPrPSc in sFI but not in sCJDMM2. This mechanism is consistent with the drastically different SE aggregate profiles engendered when PK digestion is performed on the totPrPSc before SE (a condition similar to that of the CSSA procedure) as opposed to the PK digestion of the SE-generated individual fractions. Alternatively, assuming that the stability of totPrPSc represents the average of the stabilities of both senPrPSc and resPrPSc components, the high stability of the resPrPSc even without PK treatment might compensate for the very low stability of senPrPSc. Should this be the case, stabilities of both senPrPSc and resPrPSc associated with sFI would differ from those of sCJDMM2. Regardless of these interpretations, the CSSA test uncovers an additional unexpected disparity of resPrPSc in sCJDMM2 and sFI. Stability data comparable to ours have been reported for sCJDMM2 PrPSc in previous studies18,37, along with the finding that, in sCJDMM2, senPrPSc is more stable than resPrPSc 32.

A bioassay study by Moda et al.13 showing that sCJDMM2 and sFI have quite distinct transmission properties also supports the diversity of the strains associated with these two diseases according to the classic definition of strain3. On the other hand, the notion that distinct strains generally associate with distinct phenotypes and vice versa is supported by the finding that following bioassay or direct characterization no major differences were observed in totPrPSc and resPrPSc from sCJDMM1 and sCJDMV1, two subtypes of sCJD that, despite the different genotype at codon 129, show no significant phenotypic disparity12,38. These considerations raise at least two key questions: (i) Which of the PrPSc variations in sFI and sCJDMM2 do encrypt the basic phenotypic differences of these two diseases? (ii) How can these variations be compatible with the current concepts of strain formation and evolution? Although future studies will provide more precise answers to the first question, the different representations of major components of totPrPSc like the individual glycoforms and the dimers, the differing stabilities of resPrPSc and the different aggregate profiles of both totPrPSc and resPrPSc point to the presence of fundamental differences in the two diseases involving PrPSc tertiary and quaternary structures, or the modalities of the PrPC to PrPSc conversion, both of which can likely specify distinct phenotypes22,35,39,40.

Concerning the compatibility of our findings with current prion strain notions, it is widely accepted that prion strains initially form as a spectrum of conformers, which are then prioritized through a process of Darwinian selection, with the dominant component triggering the disease and imparting its phenotypic characteristics41,42,43,44. Low compatibility of all strains with PrPC may require a conformational change of the PrP initially converted or lead to the targeting of selected PrPC conformers to allow propagation45,46. Caution must certainly be used in applying these notions (largely acquired from animal and cell experimentation) to sporadic human prion diseases in which the initial PrPSc is formed de novo, in the absence of an exogenous strain serving as template, and seemingly in circumscribed brain regions47. Nevertheless, the coexistence of significant amounts of PrPSc types 1 and 2 in about 40% of 129MM cases, combined with the finding that the disease phenotype reflects the ratio of the two types, is consistent with the presence of a selection process resulting in the co-existence of a dominant strain with sub-strains also in human sporadic prion diseases37,48,49,50,51. Other remarkable features of human sporadic prion diseases are that the variety of phenotypes and the major PrPSc species with which they are associated, regularly recur with very similar features and consistent prevalences despite the apparent lack of template. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the PrP genotype, determined by the methionine/valine polymorphism at codon 129, is a strong determinant of the prion strain. For example, in sCJD approximately 86% of the affected subjects who are methionine homozygous (sCJDMM) carry exclusively or predominantly PrPSc type 1, while the remaining 14% have PrPSc type 2 as the exclusive or prevalent type. Accordingly, the sCJDMM1 phenotype accounts for about 86% of all cases of sCJDMM while sCJDMM2 and sFI phenotypes account for up to 11.9% and 1.8%, respectively10,37, (unpublished data). According to the spectrum hypothesis, it is tempting to speculate that all three PrPSc strains (i.e. type 1MM; type 2MM and type 2MM sFI variant) are initially present in sCJDMM and sFI patients, but PrPSc type 1 is preferentially selected while the sFI strain very rarely is.

The preferential brain region where the initial PrPC to PrPSc conversion takes place might also play a role in strain selection and PrPSc properties, especially when the influence of the 129 polymorphism is expected to have no discriminating role as in sCJDMM2 and sFI52. Indirect evidence points to the thalamus as the locale of the earliest lesions in sFI, while the severe involvement of the cerebral cortex as for histopathology and PrPSc accumulation argues that the brunt of the conversions process in sCJDMM2 might take place in the cortex53,54. To deepen the current understanding of the early events in the pathogenesis and phenotypic determination in sporadic prion diseases it would be important to gain insight into how the brain locale (i.e. the biological environment) of the initial PrPC to PrPSc conversions is chosen and the role it plays in strain diversity.

Materials and Methods

See Supplementary Materials and Methods for a list of reagents and antibodies used, and for description of the following: molecular genetics, prevalence, clinical and histopathological evaluations, methanol and methanol-chloroform precipitations, deglycosylation by PNGase F, IP with 8B4, antibody co-elution, IP with OCD4, 1- and 2-D electrophoresis and immunoblot, preparation of detergent insoluble fraction with or without stringent conditions, sedimentation equilibrium and velocity.

Brain tissues and Ethics statement

Frozen brain tissues were obtained at autopsy from the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC); they included frontal cortex from controls not affected by any neurological disease (N = 3), and frontal cortex and thalamus from confirmed cases of sCJDMM2 (N = 4) and sFI (N = 4). All procedures were performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at Case Western Reserve University. Written informed consent for research was obtained from all patients or legal guardians according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients’ data and samples were coded and handled in accordance with NIH guidelines to protect patients’ identities.

Preparation of brain homogenates

Brain homogenates (BH) (10% w/v) were prepared in cold lysis buffer (LB) 100 pH 8.0 (100 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 10 mM EDTA, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0)55. Homogenization was carried out with 5 × 75 sec. cycles with high-energy cell disrupter Mini-Beadbeater-16 (BioSpec), allowing 1 min interval at 4 °C between each cycle. Solubilization was optimized by freezing the samples between cycles 3 and 4.

Sodium phosphotungstate precipitation

The original NaPTA precipitation protocol7 was modified to improve PrPC solubilization and reduce PrPC contamination in the precipitate. Homogenates were cleared by 5 min 500 × g centrifugation at 4 °C. 10% cleared homogenates, mixed 1:1 with a solution 16% sarkosyl NL in 2X D-PBS without CaCl2 and MgCl2 at pH 7.4, were well vortexed. For further details refer to Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Proteinase K digestion

Samples in LB 100 pH 8.0 were incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour with PK (58 U/mg specific activity, 1 U/ml equal to 17.2 μg/ml PK] that was adequate to efficiently digest both PrPC and senPrPSc (data not shown). The reaction was stopped by the addition of 3 mM PMSF. Unless otherwise indicated, PK digestion was performed in samples harvested from the same brain equivalents.

Determination of total protein concentration

Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit was used following the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications.

Conformational stability and solubility assay

CSSA was performed as originally described18 with minor modifications19. For further details refer to Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Statistical analysis

Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used, after determination of equal or unequal variance between the samples. The level of statistical significance was indicated: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; §P < 0.001; †P < 0.0001.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Cracco, L. et al. Novel strain properties distinguishing sporadic prion diseases sharing prion protein genotype and prion type. Sci. Rep. 7, 38280; doi: 10.1038/srep38280 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Prusiner, S. B. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 216, 136–144 (1982).

Gambetti, P. et al. Molecular biology and pathology of prion strains in sporadic human prion diseases. Acta Neuropathol 121, 79–90, doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0761-3 (2011).

Bruce, M. E., McConnell, I., Fraser, H. & Dickinson, A. G. The disease characteristics of different strains of scrapie in Sinc congenic mouse lines: implications for the nature of the agent and host control of pathogenesis. J Gen Virol 72 595–603 (1991).

Bessen, R. A. & Marsh, R. F. Distinct PrP properties suggest the molecular basis of strain variation in transmissible mink encephalopathy. J Virol 68, 7859–7868 (1994).

Monari, L. et al. Fatal familial insomnia and familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: different prion proteins determined by a DNA polymorphism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91, 2839–2842 (1994).

Telling, G. C. et al. Evidence for the conformation of the pathologic isoform of the prion protein enciphering and propagating prion diversity. Science 274, 2079–2082 (1996).

Safar, J. et al. Eight prion strains have PrP(Sc) molecules with different conformations. Nat Med. 4, 1157–1165, doi: 10.1038/2654 (1998).

Parchi, P. et al. Genetic influence on the structural variations of the abnormal prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97, 10168–10172 (2000).

Puoti, G. et al. Sporadic human prion diseases: molecular insights and diagnosis. Lancet Neurol 11, 618–628, doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(12)70063-7 (2012).

Gambetti, P., Kong, Q., Zou, W., Parchi, P. & Chen, S. G. Sporadic and familial CJD: classification and characterisation. Br Med Bull 66, 213–239 (2003).

Parchi, P. et al. Typing prion isoforms. Nature 386, 232–234, doi: 10.1038/386232a0 (1997).

Parchi, P. et al. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann Neurol 46, 224–233 (1999).

Moda, F. et al. MM2-thalamic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: neuropathological, biochemical and transmission studies identify a distinctive prion strain. Brain Pathol 22, 662–669, doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2012.00572.x (2012).

Pan, T. et al. Biochemical fingerprints of prion diseases: scrapie prion protein in human prion diseases that share prion genotype and type. J Neurochem 92, 132–142, doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02859.x (2005).

Notari, S. et al. Characterization of truncated forms of abnormal prion protein in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Biol Chem 283, 30557–30565, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801877200 (2008).

Zou, W. Q., Zheng, J., Gray, D. M., Gambetti, P. & Chen, S. G. Antibody to DNA detects scrapie but not normal prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 1380–1385, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307825100 (2004).

Yuan, J. et al. Insoluble aggregates and protease-resistant conformers of prion protein in uninfected human brains. J Biol Chem 281, 34848–34858, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602238200 (2006).

Pirisinu, L. et al. A new method for the characterization of strain-specific conformational stability of protease-sensitive and protease-resistant PrP. PLoS One 5, e12723, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012723 (2010).

Cali, I. et al. Co-existence of PrPSc types 1 and 2 in sporadic CJD with genotype 129VV. Prion 6 Supplement, 134–135 (2012).

Saverioni, D. et al. Analyses of protease resistance and aggregation state of abnormal prion protein across the spectrum of human prions. J Biol Chem 288, 27972–27985, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.477547 (2013).

Makarava, N., Savtchenko, R. & Baskakov, I. V. Selective amplification of classical and atypical prions using modified protein misfolding cyclic amplification. J Biol Chem 288, 33–41, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419531 (2013).

Poggiolini, I., Saverioni, D. & Parchi, P. Prion protein misfolding, strains, and neurotoxicity: an update from studies on Mammalian prions. Int J Cell Biol 2013, 910314, doi: 10.1155/2013/910314 (2013).

Xiao, X. et al. Glycoform-selective prion formation in sporadic and familial forms of prion disease. PLoS One 8, e58786, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058786 (2013).

Katorcha, E., Makarava, N., Savtchenko, R. & Baskakov, I. V. Sialylation of the prion protein glycans controls prion replication rate and glycoform ratio. Sci Rep 5, 16912, doi: 10.1038/srep16912 (2015).

Wiseman, F. K. et al. The glycosylation status of PrPC is a key factor in determining transmissible spongiform encephalopathy transmission between species. J Virol 89, 4738–4747, doi: 10.1128/JVI.02296-14 (2015).

Safar, J. G. et al. Structural determinants of phenotypic diversity and replication rate of human prions. PLoS Pathog 11, e1004832, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004832 (2015).

Bendheim, P. E. & Bolton, D. C. A 54-kDa normal cellular protein may be the precursor of the scrapie agent protease-resistant protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83, 2214–2218 (1986).

Priola, S. A., Caughey, B., Wehrly, K. & Chesebro, B. A 60-kDa prion protein (PrP) with properties of both the normal and scrapie-associated forms of PrP. J Biol Chem 270, 3299–3305 (1995).

Biasini, E. et al. Immunopurification of pathological prion protein aggregates. PLoS One 4, e7816, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007816 (2009).

Pan, T. et al. Novel differences between two human prion strains revealed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. J Biol Chem 276, 37284–37288, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107358200 (2001).

Morales, R. et al. Strain-dependent profile of misfolded prion protein aggregates. Sci Rep 6, 20526, doi: 10.1038/srep20526 (2016).

Kim, C. et al. Small protease sensitive oligomers of PrPSc in distinct human prions determine conversion rate of PrP(C). PLoS Pathog 8, e1002835, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002835 (2012).

Deleault, N. R. et al. Isolation of phosphatidylethanolamine as a solitary cofactor for prion formation in the absence of nucleic acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 8546–8551, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204498109 (2012).

Deleault, N. R. et al. Cofactor molecules maintain infectious conformation and restrict strain properties in purified prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, E1938–1946, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206999109 (2012).

Baskakov, I. V. The many shades of prion strain adaptation. Prion 8 (2014).

Supattapone, S. Synthesis of high titer infectious prions with cofactor molecules. J Biol Chem 289, 19850–19854, doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.511329 (2014).

Cali, I. et al. Co-existence of scrapie prion protein types 1 and 2 in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: its effect on the phenotype and prion-type characteristics. Brain 132, 2643–2658, doi: 10.1093/brain/awp196 (2009).

Bishop, M. T., Will, R. G. & Manson, J. C. Defining sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease strains and their transmission properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 12005–12010, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004688107 (2010).

Li, J., Mahal, S. P., Demczyk, C. A. & Weissmann, C. Mutability of prions. EMBO Rep 12, 1243–1250, doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.191 (2011).

Laferrière, F. et al. Quaternary structure of pathological prion protein as a determining factor of strain-specific prion replication dynamics. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003702, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003702 (2013).

Collinge, J. & Clarke, A. R. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science 318, 930–936, doi: 10.1126/science.1138718 (2007).

Collinge, J. Medicine. Prion strain mutation and selection. Science 328, 1111–1112, doi: 10.1126/science.1190815 (2010).

Li, J., Browning, S., Mahal, S. P., Oelschlegel, A. M. & Weissmann, C. Darwinian evolution of prions in cell culture. Science 327, 869–872, doi: 10.1126/science.1183218 (2010).

Imberdis, T. & Harris, D. A. Synthetic Prions Provide Clues for Understanding Prion Diseases. Am J Pathol 186, 761–764, doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.12.005 (2016).

Weissmann, C., Li, J., Mahal, S. P. & Browning, S. Prions on the move. EMBO Rep 12, 1109–1117, doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.192 (2011).

Makarava, N., Savtchenko, R., Alexeeva, I., Rohwer, R. G. & Baskakov, I. V. New Molecular Insight into Mechanism of Evolution of Mammalian Synthetic Prions. Am J Pathol 186, 1006–1014, doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.11.013 (2016).

Gambetti, P. Creationism and evolutionism in prions. Am J Pathol 182, 623–627, doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.016 (2013).

Puoti, G. et al. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: co-occurrence of different types of PrP(Sc) in the same brain. Neurology 53, 2173–2176 (1999).

Parchi, P. et al. Incidence and spectrum of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease variants with mixed phenotype and co-occurrence of PrPSc types: an updated classification. Acta Neuropathol 118, 659–671, doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0585-1 (2009).

Weissmann, C. Mutation and selection of prions. PLoS Pathog 8, e1002582, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002582 (2012).

Haldiman, T. et al. Co-existence of distinct prion types enables conformational evolution of human PrPSc by competitive selection. J Biol Chem 288, 29846–29861, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.500108 (2013).

Beringue, V. et al. Facilitated cross-species transmission of prions in extraneural tissue. Science 335, 472–475, doi: 10.1126/science.1215659 (2012).

Parchi, P. et al. A subtype of sporadic prion disease mimicking fatal familial insomnia. Neurology 52, 1757–1763 (1999).

Cortelli, P. et al. Pre-symptomatic diagnosis in fatal familial insomnia: serial neurophysiological and 18FDG-PET studies. Brain 129, 668–675, doi: 10.1093/brain/awl003 (2006).

Notari, S. et al. Effects of different experimental conditions on the PrPSc core generated by protease digestion: implications for strain typing and molecular classification of CJD. J Biol Chem 279, 16797–16804, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313220200 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients’ families, the CJD Foundation and all the members of the NPDPSC, in particular Mses. Yvonne Cohen, Diane Kofskey, Miriam Warren, Katie Glisic, Janis Blevins and Mr. Aaron Foutz. We also are grateful to Dr. Gianluigi Zanusso for assistance with 2-D data and Ms. Laura Grossi for manuscript editing. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 NS083687 and P01 AI106705, and The Charles S. Britton Fund (to P.G.); in part by CDC Grant U51 CK000100 (to J.G.S.), the Intramural Research Program of the NIAID (to B.C.) and Grant P30 AG010133 (to B.G.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: P.G., L.C., S.N., B.C., I.C. and J.G.S. Performed the experiments: L.C. and W.-Q.Z. Analyzed the data: P.G., L.C., S.N., B.C., I.C. and J.G.S. Performed clinical review: B.S.A. Performed histopathological examinations and made final diagnoses: P.G. and M.L.C. Contributed materials: M.-S.S., S.G.C. and B.G. Wrote the paper: P.G. and L.C. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cracco, L., Notari, S., Cali, I. et al. Novel strain properties distinguishing sporadic prion diseases sharing prion protein genotype and prion type. Sci Rep 7, 38280 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38280

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38280

This article is cited by

-

Cryo-EM structures of prion protein filaments from Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker disease

Acta Neuropathologica (2022)

-

Prion protein oligomers cause neuronal cytoskeletal damage in rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s disease

Molecular Neurodegeneration (2021)

-

Environmental and host factors that contribute to prion strain evolution

Acta Neuropathologica (2021)

-

A novel mechanism of phenotypic heterogeneity in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2020)

-

Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease revisited: accumulation of covalently-linked multimers of internal prion protein fragments

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.