Abstract

We report on the synthesis and electrical properties of nine new alkylated silane self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) – (EtO)3Si(CH2)nN = CHPhX where n = 3 or 11 and X = 4-CF3, 3,5-CF3, 3-F-4-CF3, 4-F, or 2,3,4,5,6-F, and explore their rectification behavior in relation to their molecular structure. The electrical properties of the films were examined in a metal/insulator/metal configuration, with a highly-doped silicon bottom contact and a eutectic gallium-indium liquid metal (EGaIn) top contact. The junctions exhibit high yields (>90%), a remarkable resistance to bias stress, and current rectification ratios (R) between 20 and 200 depending on the structure, degree of order, and internal dipole of each molecule. We found that the rectification ratio correlates positively with the strength of the molecular dipole moment and it is reduced with increasing molecular length.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Molecular electronics has been an area of great interest as device technology closes on the limits of the often-mentioned Moore’s law, with consumer-available technology already in the tens of nanometers range. The idea of molecular electronics was proposed as a means to surpass the challenges present in downscaling existing technologies1,2,3; however, commercially viable examples have yet to be introduced4,5,6,7,8. Since 1974, when Aviram and Ratner proposed the first rectification mechanism for a molecular structure containing a donor-acceptor pair separated by a σ-bonded tunnelling bridge, the field has witnessed spectacular growth9. A rectifier is a device which allows a large amount of current to pass through at one bias while restricting current flow at the opposite bias. While the above mentioned theoretical work extrapolated the inorganic solid state p-n junction miniaturized to the size of a single molecule and relied on the manipulation of the molecule’s energy levels, several different mechanisms for enhanced rectifications have subsequently been proposed10,11,12,13. Further experimental work has also demonstrated that the donor-acceptor pair may not always be necessary, and that systems with a single π-bonded component and a σ-bonded insulating chain can provide a more consistent, as well as a greater degree of, rectification14,15,16. Significant research effort was dedicated toward the examination of both single-molecule and molecular assemblies as rectifiers, with clear advantages exhibited by both17,18,19,20. Single molecule devices allow for a direct comparison with the theoretical calculations due to the lack of complexity in such systems. Nevertheless, Nijhuis et al. produced convincing arguments for the observed rectification in ferrocene-terminated alkanethiolate molecules assembled on surfaces in monolayer patterns21,22,23. Other self-assembled monolayers and Langmuir-Blodgett films provide ease of fabrication due to the molecule’s penchant for assembling on a well-chosen surface. This allows for the formation of many devices on a single substrate simultaneously and without the difficult alignment task present in single-molecule structures. The research to improve the rectifying behaviour of molecular diodes, however, has proceeded mostly by trial and error and a relation between the molecular structure and resulting strength of rectification has not been clearly demonstrated.

In this work, we developed nine new fluorinated benzalkylsilane molecules of varying internal molecular dipole due to the imposed length and termination, and we studied their electrical properties in relation to their chemical structure. We incorporated the self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) composed of these molecules into molecular diodes and obtained high yields and reproducible rectification ratios as high as 200, with good bias stress stability. We calculated the molecular dipole using density functional theory (DFT) and we found that the rectifying behaviour is stronger in the case of short molecules and is enhanced by the internal dipole. Our results provide evidence that the molecular structure impacts the electrical properties of molecular diodes through the internal dipole characteristic to each molecule, and may promote a rational design of compounds that can function as high-performance molecular rectifiers.

Results

Molecular Structures and Analysis

The examined molecules were fluorine-substituted benzaldehyde imine-terminated trialkoxysilanes, designed such that each contains a triethoxysilane group that ensures the attachment on the Si/SiO2 surface, an alkyl chain with either 3 or 11 CH2 groups, a phenyl group to facilitate the formation of an “intermolecular top-link” to enhance ordering, and a fluorine-containing head-group providing different amounts and orientations of fluorine atoms24. The chemical structures are included in Fig. 1, as follows: (E)-1-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-N-(11-(triethoxysilyl)undecyl)methanimine (molecule 1), (E)-1-(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-N-(11-(triethoxysilyl)undecyl)methanimine (molecule 2), (E)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-N-(11-(triethoxysilyl)undecyl) methanimine (molecule 3), (E)- 1-(3-fluoro-4-trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-N-(11-(triethoxysilyl)undecyl)methanimine (molecule 4), (E)-1-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-N-(3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl)methanimine (molecule 5), (E)-1-(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-N-(3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl) methanimine (molecule 6), (E)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-N-(3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl) methanimine (molecule 7), (E)- 1-(3-fluoro-4-trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-N-(3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl)methanimine (molecule 8) and (E)-1-(perfluorophenyl)-N-(3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl) methanimine (molecule 9). (E)-1-(perfluorophenyl)-N-(11-(triethoxysilyl)undecyl) methanimine (the long chain analogue of molecule 9) was also investigated; its properties, however, varied significantly from sample to sample, as well as for the same film, and therefore we decided not to include it in our analysis. The molecules were synthesized from amino trialkoxysilanes by using the condensation of commercially available amino alkyl triethoxysilanes with substituted benzaldehydes to prepare the precursors, following established procedures (see Fig. SI 1, Supporting Information)25,26. We will refer to molecules 1, 2, 3, and 4 as the “long molecules” (their lengths are between 2 and 2.2 nm) and molecules 5 through 9 as the “short molecules” (their lengths are between 0.9 and 1.1 nm). The length was evaluated using Spartan software, measured from the Si atom to the most distal atom of the head-group for the lowest energy conformer of each molecule.

Device Fabrication

To examine their electrical properties, the SAMs were deposited on highly-doped, natively oxidized silicon (001) wafers using solution or vapor-based deposition, as described in the Methods section.

Surface Analysis

In order to evaluate the quality of the SAM and the best method for assembly, water contact angle measurements were conducted using a Ramé-Hart Model 200 Contact Angle Goniometer; the results are displayed in Table 1 and in Fig. SI 2, Supporting Information. A high value of the contact angle generally coincides with a higher degree of order and/or a denser film27. Indeed, the contact angles measured for all the SAMs were around 70°. These values agree with the measurements performed on other fluorinated SAMs deposited on SiO228. For reference, we have also measured the contact angle on untreated substrates, and that is displayed in the same figure. It can be observed that the contact angle for bare native SiO2 is <10°.

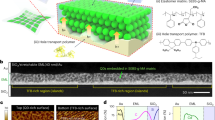

We employed atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements to characterize the surface roughness prior to SAM deposition. We measured a sample of 1 cm × 1 cm and imaged a surface area of approximately 2 × 2 μm in several spots using a Nanoscope IIIA AFM (Veeco Instruments), see Fig. 2. This surface is of similar quality to that obtained using template stripped or flip-chip laminated metallic electrodes22,29. The roughness value is over an order of magnitude smaller than the height of the molecules studied here, including the shortest one, and therefore it is largely inconsequential with regard to the assembly of a film, allowing for the formation of a highly ordered film when the processing parameters are carefully tuned. A graphical illustration of this can be seen in Fig. 2(c), where we schematically show the assembly of a long and a short molecule studied here and the respective difference in the length scales of the substrate and molecules.

The work function measurements on highly doped silicon were performed using a Trek model 325 electrostatic voltmeter configured for Kelvin probe measurements and calibrated using highly-ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) as a standard. The calculations followed from equation 1:

where e is the elementary charge,  is the measured signal from the substrate (Si with a native layer of SiO2),

is the measured signal from the substrate (Si with a native layer of SiO2),  is the measured signal from HOPG, and

is the measured signal from HOPG, and  is the work function of HOPG (

is the work function of HOPG ( )30. Four samples were evaluated, in at least 8 spots, and the results were consistent: we obtained a work function of

)30. Four samples were evaluated, in at least 8 spots, and the results were consistent: we obtained a work function of  for the highly doped Si substrates with a thin layer of native oxide on their surface.

for the highly doped Si substrates with a thin layer of native oxide on their surface.

Electrical Characterization

The electrical measurements were taken on metal/SAM/metal structures using a eutectic gallium-indium (EGaIn) conical-tip top contact in which the silicon substrate was held at ground and the bias was applied to the EGaIn contact in ambient conditions. In this configuration, the forward bias condition corresponds to a positive potential applied at the fluorinated end of the molecules. The eutectic liquid metal EGaIn was utilized as a soft top-contact because its use is non-damaging, reproducible, and well-studied in this context22,23,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. A schematic of the device structure used in this study is included in Fig. 3(a). This figure, however, denotes an ideal structure of the device, while we are aware that our SAM layers may exhibit a lower degree of order, different orientation with respect to the substrate, and possible step-edges due to substrate imperfections, impurities, etc.

(a) Schematic of device structure showing a SAM sandwiched between the native SiO2 bottom contact and EGaIn top contact. (b) Current density versus the applied voltage on 25 different spots in a 1 cm × 1 cm area on a film consisting of molecule 3. (c) Bias stress measurements on molecule 6 over 50 consecutive measurements in a single spot.

Ab Initio Calculations

We performed ab initio calculations at the density functional theory level, using VASP39,40. We used the standard projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials provided by VASP along with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional41,42. All calculations were done with a kinetic-energy cutoff of 400 eV and an energy convergence criterion of 10−4 eV. Calculations were performed in orthorhombic unit cells with a vacuum of at least 2 nm between periodic images. All structures were relaxed until the maximum force on any atom was less than 10 meV/angstrom. Dipole moments were calculated using VASP’s built-in functionality to calculate and correct for the dipole moment in all directions (i.e. the IDIPOL and LDIPOL tags).

Electrical Properties of Molecular Diodes

In Fig. 3(b) we show the dependence of the current density (J) on the applied voltage (V) for one film of molecule 3, in 25 different spots. The relative standard deviation for these measurements is <1.4. Measurements on different spots on the films are consistent, suggesting that our SAMs are uniform. In addition, for a particular SAM to be considered viable as a rectifier, it must be able to withstand many repetitive measurements with minimum changes in the electrical characteristics. This could involve a variability and instability in the measured output characteristics or, in the worst-case scenario, a “breaking” of the monolayer, indicating that there is now an irreversible conductive path between the two electrodes. The good operational stability, as clearly seen in Fig. 3(c) for molecule 5, where we show the results of 50 consecutive measurements, indicates that these monolayers are robust to bias stress (the relative standard deviation is less than 0.21). The difference between Fig. 3(b) and (c) at low voltages originates from the fact that charging effects may occur when repeated measurements are taken on the same spot on the film (Fig. 3(c)), causing noise and asymmetries in the measured current. We note, however, that applying higher voltages may result in irreversible damage of the SAM film. The breakdown field in these SAMs range from approximately 20 MV/cm for molecule 9 to 50 MV/cm for molecule 5.

Figure 4 shows typical current-voltage (J-V) characteristics for each of the 9 molecules, taken during the forward and reverse bias conditions. We measured at least 10 devices for each type of SAM, in at least 25 spots each, and obtained similar results. As expected, the magnitude of the measured current depends on the molecular structure, with the long molecules generally exhibiting lower conductivities and less pronounced asymetries between the forward and reverse bias conditions.

Discussion

We define the rectification ratio, R, as the ratio between the J value during the forward bias measurement, (V = +2 V) and the J value during the reverse bias measurement, (V = −2 V):

In Table 1 we list the R values obtained for the nine molecules. In order to relate the electrical properties with the molecular structure, we determined the electrical dipole of each molecule using DFT calculations; results are listed in Table 1. In Fig. 5 we plot the dependence of R on the molecular dipole for all the molecules investigated in this study. Results obtained for short molecules are included in red, while those for long ones are shown in grey. First, note the high value of R obtained for molecule 5 and 8, R5 = 183 ± 41 and R8 = 192 ± 42. These values are on par with some of the highest reported in the literature, with a thiophene-1,1-dioxide oligomer exhibiting an R of ~200, a ferrocene-alkanethiolate with an R = 150, and ferrocene placed on a monolayer of β-cyclodextrin demonstrating an R of 17015,33,43. We note, however, that larger values can also be obtained44,45. Nevertheless, our molecules have the additional advantage of being very low-cost since the precursors are common organic molecules, being easy to synthesize, and requiring minimal purification steps. This figure also denotes that a stronger rectification is achieved in the case of short molecules, in agreement with previous reports46,47. Another key point that can be observed from Fig. 5 is that for molecules of similar length, the rectification ratio correlates positively with the internal dipole moment of each molecule. This trend can originate from the fact that the molecular dipole creates a local electric field proportional to the magnitude of the dipole moment. This field contributes to the total net field experienced by the molecule under external bias, modifying the shape of the tunnelling barrier, and, consequently, of the current magnitude. Although a detailed interpretation of this dependence is beyond the scope of this manuscript, the results suggest that for molecules of similar length, the rectification increases with the molecular dipole, regardless of structural details of each compound. The trend is monotonic for the case of short molecules, and we note that there is a spread in our data for the long molecules. On one hand, this may originate from variations in molecular orientation and the degree of order of the SAMs on the surfaces, which results from the competition between intermolecular interactions of the SAM molecules and molecule-substrate interactions. We attempted to characterize the ordering of the SAMs through polarized modulated-infrared reflection absorption spectroscopy (PM-IRRAS) and X-ray reflectivity measurements, both of which were unsuccessful due to the small size of the molecular layers. On the other hand, local molecular torsions and changes in the conformation were shown to significantly impact the value of the rectification ratio48,49. Several other factors may contribute in the observed asymmetries. First, the two contacts are not perfectly symmetric: a strong, Si-O covalent bond is established between the SAM and the bottom contact, while the top contact interacts with the SAM via a weak, van der Waals bond established between the end-group of the SAM and the Ga2O3 layer formed at the surface of the EGaIn electrode22. The strength of this bond, and therefore the rate of charge tunnelling, may vary with changing the chemistry of the SAM fluorinated functional group. In addition, these contacts have slightly different work-functions ( = 4.65 ± 0.05 eV, as determined from Kelvin probe measurements described above, while

= 4.65 ± 0.05 eV, as determined from Kelvin probe measurements described above, while  = 4.1–4.2 eV50), which impact the injection of charge carriers. Second, additional dipole moments may be formed through band-bending when physical contact is established between the SAM and electrodes. Nevertheless, the dependence is clearly distinguished and this suggests that tailoring the internal molecular dipole via molecular design may be a powerful tool in controlling the rectification ratios in molecular diodes. This result may seem to contradict that of Yoon and collaborators, who showed that the rectification behaviour of molecular diodes is independent of their molecular dipole12. In that study, however, the molecules had various lengths, and therefore the dependence may have been masked. Further studies, focusing on the examination of properties of different classes of compounds—including compounds with dipole moments in opposite directions—as well as studies on SAMs of different anchoring and terminal groups would clarify the generality and limitations of this method.

= 4.1–4.2 eV50), which impact the injection of charge carriers. Second, additional dipole moments may be formed through band-bending when physical contact is established between the SAM and electrodes. Nevertheless, the dependence is clearly distinguished and this suggests that tailoring the internal molecular dipole via molecular design may be a powerful tool in controlling the rectification ratios in molecular diodes. This result may seem to contradict that of Yoon and collaborators, who showed that the rectification behaviour of molecular diodes is independent of their molecular dipole12. In that study, however, the molecules had various lengths, and therefore the dependence may have been masked. Further studies, focusing on the examination of properties of different classes of compounds—including compounds with dipole moments in opposite directions—as well as studies on SAMs of different anchoring and terminal groups would clarify the generality and limitations of this method.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have designed, synthesized, and measured nine new rectifying self-assembled monolayers of different lengths and polar terminations. We found that these fluorinated benzalkylsilane molecules exhibit high yield when incorporated in molecular diodes, coupled with robust rectification ratios ranging from 20–200, depending on their structure. In addition, they show good uniformity over large surface areas and excellent bias stress stability. We found an increase in the rectification strength with enhancing the internal molecular dipole of each molecule. Our results suggest that the electrical properties of molecular diodes can be controlled by tailoring the molecular structures of the constituent molecules. This is a significant step toward controlling the performance of molecular rectifiers through manipulating specific structure-property relationships for use in macroscopic electronics as diodes, half-wave rectifiers, AC/DC converters, or other charge-restricting elements.

Methods

The molecules were synthesized from amino trialkoxysilanes by using standard procedures (see Fig. SI 1). With the exception of one imine, see Fig. SI 1, the yields for all of these reactions were in the 68–87% range and the only purification of the products required after the reaction was filtration and removal of residual solvent under high vacuum. The new compounds were characterized by 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and elemental analysis or high-resolution mass spectrometry (see Supporting Information for synthesis and characterization details).

The SAMs were deposited on highly-doped silicon wafers with native SiO2 formed at their surface by either solution or vapor-based techniques. The substrates were cleaned in hot acetone, then hot isopropanol (IPA), followed by a 10 minute exposure to UV-ozone and subsequent rinse in DI water before being dried in a stream of nitrogen. The UV-ozone step serves to both remove organic contaminants and to increase the density of hydroxyl groups on the surface. The monolayers were formed in a nitrogen (<0.1 ppm H2O, <0.1 ppm O2) glovebox. We found that for the long SAMs (molecules 1, 2, 3, and 4) self-assembly from a 4 mMol solution in chloroform at 30 °C provided the films of highest quality. The short SAMs (molecules 5 through 9) were amenable to deposition by vapor treatment, where the silicon wafer was placed into a sealed jar along with 11 μL of the pure SAM compound at 30 °C. Both methods typically took 18 to 24 hours. To remove the excess adsorbed molecules on the monolayer surface, the samples were thoroughly rinsed in chloroform followed by IPA and then immediately dried in a stream of nitrogen.

The conical-tip EGaIn contact, which was used as a top soft contact for our molecular rectifiers, was created using a Micromanipulator probe holder, and a 0.5 mm diameter Micromanipulator probe tip. EGaIn was placed onto a sacrifical copper strip into which the probe tip was slowly lowered and then raised with the aid of the contact angle goniometer.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lamport, Z. A. et al. Fluorinated benzalkylsilane molecular rectifiers. Sci. Rep. 6, 38092; doi: 10.1038/srep38092 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Collier, C. P. Electronically Configurable Molecular-Based Logic Gates. Science 285, 391–394 (1999).

Reed, M. A., Chen, J., Rawlett, A. M., Price, D. W. & Tour, J. M. Molecular random access memory cell. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 3735 (2001).

Green, J. E. et al. A 160-kilobit molecular electronic memory patterned at 10(11) bits per square centimetre. Nature 445, 414–417 (2007).

Rascón-Ramos, H., Artés, J. M., Li, Y. & Hihath, J. Binding configurations and intramolecular strain in single-molecule devices. Nat. Mater. 14, 1–6 (2015).

Haedler, A. T. et al. Long-range energy transport in single supramolecular nanofibres at room temperature. Nature 523, 196–199 (2015).

Xiang, D., Wang, X., Jia, C., Lee, T. & Guo, X. Molecular-Scale Electronics: From Concept to Function. Chem. Rev. acs.chemrev. 5b00680, doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00680 (2016).

Lörtscher, E. Wiring molecules into circuits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 381–384 (2013).

Metzger, R. M. Unimolecular Electronics. Chem. Rev. 115, 5056–5115 (2015).

Aviram, A. & Ratner, M. A. Molecular rectifiers. Chem. Phys. Lett. 29, 277 (1974).

Akkerman, H. B. & de Boer, B. Electrical conduction through single molecules and self-assembled monolayers. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 13001 (2007).

Metzger, R. M. Unimolecular electrical rectifiers. Chem. Rev. 103, 3803–3834 (2003).

Yoon, H. J., Bowers, C. M., Baghbanzadeh, M. & Whitesides, G. M. The Rate of Charge Tunneling Is Insensitive to Polar Terminal Groups in Self-Assembled Monolayers in Ag TS S(CH 2) n M(CH 2) m T//Ga 2 O 3/EGaIn Junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16–19 (2014).

Lenfant, S., Krzeminski, C., Delerue, C., Allan, G. & Vuillaume, D. Molecular rectifying diodes from self-assembly on silicon. Nano Lett. 3, 741–746 (2003).

Kornilovitch, P. E., Bratkovsky, A. M. & Williams, R. S. Current rectification by molecules with asymmetric tunneling barriers. Phys. Rev. B 66, 165436 (2002).

Nerngchamnong, N. et al. The role of van der Waals forces in the performance of molecular diodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 113–8 (2013).

Aswal, D. K., Lenfant, S., Guerin, D., Yakhmi, J. V. & Vuillaume, D. Self assembled monolayers on silicon for molecular electronics. Anal. Chim. Acta 568, 84–108 (2006).

Akkerman, H. B., Blom, P. W. M., de Leeuw, D. M. & de Boer, B. Towards molecular electronics with large-area molecular junctions. Nature 441, 69–72 (2006).

Ashwell, G. J., Tyrrell, W. D. & Whittam, A. J. Molecular rectification: Self-assembled monolayers in which donor-(π-bridge)-acceptor moieties are centrally located and symmetrically coupled to both gold electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 7102–7110 (2004).

Elbing, M. et al. A single-molecule diode. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 8815–20 (2005).

Díez-Pérez, I. et al. Rectification and stability of a single molecular diode with controlled orientation. Nat. Chem. 1, 635–641 (2009).

Batra, A. et al. Tuning rectification in single-molecular diodes. Nano Lett. 13, 6233–6237 (2013).

Nijhuis, C. A., Reus, W. F. & Whitesides, G. M. Molecular rectification in metal-SAM-metal oxide-metal junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 17814–17827 (2009).

Nijhuis, C. A., Reus, W. F. & Whitesides, G. M. Mechanism of rectification in tunneling junctions based on molecules with asymmetric potential drops. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 18386–18401 (2010).

Halik, M. et al. Low-voltage organic transistors with an amorphous molecular gate dielectric. Nature 431, 963–6 (2004).

Ladilina, E. Y. et al. Carbofunctional fluorine-containing triethoxysilanes: synthesis, film forming and properties. Russ. Chem. Bull. 54, 1160–1168 (2005).

Hicks, J. C., Dabestani, R., Buchanan, A. C. & Jones, C. W. Spacing and Site Isolation of Amine Groups in 3-Aminopropyl-Grafted Silica Materials: The Role of Protecting Groups. Chem. Mater. 18, 5022–5032 (2006).

Allara, D. L. & Nuzzo, R. G. Spontaneously organized molecular assemblies. 1. Formation, dynamics, and physical properties of n-alkanoic acids adsorbed from solution on an oxidized aluminum surface. Langmuir 1, 45–52 (1985).

Pernstich, K. P. et al. Threshold voltage shift in organic field effect transistors by dipole monolayers on the gate insulator. J. Appl. Phys. 96, 6431 (2004).

Coll, M. et al. Formation of silicon-based molecular electronic structures using flip-chip lamination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 12451–7 (2009).

Ward, J. W. et al. Tailored Interfaces for Self-Patterning Organic Thin-Film Transistors. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 19047–19053 (2012).

Chiechi, R. C., Weiss, E. A., Dickey, M. D. & Whitesides, G. M. Eutectic Gallium–Indium (EGaIn): A Moldable Liquid Metal for Electrical Characterization of Self-Assembled Monolayers. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 47, 142–144 (2008).

Nijhuis, C. A., Reus, W. F., Barber, J. R., Dickey, M. D. & Whitesides, G. M. Charge transport and rectification in arrays of SAM-based tunneling junctions. Nano Lett. 10, 3611–3619 (2010).

Wimbush, K. S. et al. Control over rectification in supramolecular tunneling junctions. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 49, 10176–10180 (2010).

Nijhuis, C. A., Reus, W. F., Siegel, A. C. & Whitesides, G. M. A molecular half-wave rectifier. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 15397–15411 (2011).

Reus, W. F., Thuo, M. M., Shapiro, N. D., Nijhuis, C. A. & Whitesides, G. M. The SAM, not the electrodes, dominates charge transport in metal-monolayer//Ga2O3/gallium-indium eutectic junctions. ACS Nano 6, 4806–22 (2012).

Yoon, H. J. et al. Rectification in Tunneling Junctions: 2,2′-Bipyridyl-Terminated n -Alkanethiolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 17155–17162 (2014).

Lefèvre, X. et al. Influence of Molecular Organization on the Electrical Characteristics of π-Conjugated Self-Assembled Monolayers. J. Phys. Chem. C 150303145525000, doi: 10.1021/jp512991d (2015).

Jiang, L., Sangeeth, C. S. S., Wan, A., Vilan, A. & Nijhuis, C. A. Defect Scaling with Contact Area in EGaIn-Based Junctions: Impact on Quality, Joule Heating, and Apparent Injection Current. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 960–969 (2015).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Capozzi, B. et al. Single-molecule diodes with high rectification ratios through environmental control. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 522–527 (2015).

Yuan, L., Breuer, R., Jiang, L., Schmittel, M. & Nijhuis, C. A. A Molecular Diode with a Statistically Robust Rectification Ratio of Three Orders of Magnitude. Nano Lett. 15, 5506–5512 (2015).

Garg, K. et al. Silicon-pyrene/perylene hybrids as molecular rectifiers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 1891–1899 (2015).

Luo, L. et al. Hopping Transport and Rectifying Behavior in Long Donor–Acceptor Molecular Wires. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 26485–26497 (2014).

Mativetsky, M., Loo, Y. & Samor, P. Elucidating the nanoscale origins of organic electronic function by conductive atomic force. J. Mater. Chem. C 3118–3128, doi: 10.1039/c3tc32050b (2014).

Cui, B. et al. Effect of geometrical torsion on the rectification properties of diblock conjugated molecular diodes. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 73701 (2014).

Mativetsky, J. M. et al. Azobenzenes as light-controlled molecular electronic switches in nanoscale metal-molecule-metal junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 9192–9193 (2008).

Chiechi, R. C., Weiss, E. A., Dickey, M. D. & Whitesides, G. M. Eutectic Gallium–Indium (EGaIn): A Moldable Liquid Metal for Electrical Characterization of Self-Assembled Monolayers. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 47, 142–144 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the WFU Pilot Research Grant and NSF under award ECCS 1254757.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L., K.B. and O.J. fabricated and characterised the molecular rectifier devices, A.B., L.M., C.H. and M.W. synthesized the molecules, D.H. and T.T. performed the dipole moment calculations, M.G. performed the AFM measurements. M.G., T.T., M.W. and O.J. supervised the project, all authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lamport, Z., Broadnax, A., Harrison, D. et al. Fluorinated benzalkylsilane molecular rectifiers. Sci Rep 6, 38092 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38092

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38092

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.