Abstract

Environmental heterogeneity is considered to play a defining role in promoting invasion success, and it favours clonal plants. Although clonality has been demonstrated to be correlated with the invasion success of several species of clonal invasive plants in heterogeneous environments, little is known about how the spatial scale of heterogeneity affects their performance. In addition, the factors that distinguish invasive from non-invasive clonal species and that enhance the invasive potential of clonal exotic invaders in heterogeneous environments remain unclear. In this study, we compared several traits of a noxious clonal invasive species, Alternanthera philoxeroides, with its co-occurring non-invasive functional counterparts, the native congener Alternanthera sessilis, the exotic Myriophyllum aquaticum and the native Jussiaea repens, in three manipulative substrates with different soil distribution patterns. We found that the invasive performance of A. philoxeroides was not enhanced by heterogeneity and that it was generally scale independent. However, A. philoxeroides showed some advantages over the three non-invasives with respect to trait values and phenotypic variation. These advantages may enhance the competitive capacity of A. philoxeroides and thus promote its invasion success in heterogeneous environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental heterogeneity plays a significant role in biological invasion1,2,3,4,5. The capacity of clonal growth/production has been considered as a pivotal attribute of exotic invasive clonal plants when facing environmental heterogeneity6,7,8. Clonal stoloniferous plants benefit from environmental heterogeneity because clonal traits (e.g., clonal integration and spatial division of labour) enhance resource exploitation, nutrient exchange and risk spread9,10,11. Hence, environmental heterogeneity favours clonal growth12. However, the optimality of clonal growth in heterogeneous environments is scale dependent13. For instance, a negative correlation between clonal plant performance and patch size has been demonstrated by several studies14,15. Moreover, the “environmental heterogeneity hypothesis of invasions” suggests that environmental heterogeneity can promote the invasion success of exotic species16. Thus, environmental heterogeneity is likely to promote the performance of invasive clonal plants. Moreover, the performance of invasive clonal plants in heterogeneous environments may be correlated with the spatial scale of heterogeneity.

Trait comparison of co-occurring invasive and non-invasive species to reveal the competitive advantages of invasives over non-invasives generally focuses on two aspects related to invasion mechanisms – trait values and trait plasticity17,18. A competitive advantage of invasives in trait values refers to advantageous novel traits or extreme trait values of invasive plant species in comparison with non-invasives19. Some studies have proposed that invasive plant species display higher values of specific leaf area (SLA), relative growth rate (RGR), body size and belowground traits such as root mass ratio (RMR) and R/S ratio compared with their co-occurring non-invasive species19,20,21. In addition to exhibiting these common traits, stoloniferous clonal plants possess a unique trait of clonality. Invasive clonal plants likely possess a stronger potential of clonality (e.g., clonal integration, spatial division of labour) than do co-occurring, non-invasive clonal species8. This stronger potential is expected to facilitate the integration of unevenly distributed resources by invasive clonal plants in heterogeneous environments and thus enhance their performance10,13,14,15,22. These trait value advantages may promote the rapid colonization and efficient establishment of invasive species in novel and heterogeneous environments.

Trait plasticity refers to the property of phenotypic variation of a genotype in variable environments23. Empirical studies have indicated that phenotypic plasticity plays a significant role in biological invasions17,24,25,26,27,28. Adaptive plasticity enables species to extend ecological niche breadth as plastic responses promote advantageous trait expressions in different environments23,29,30. Greater plasticity of invasive species over non-invasive species may help explain the invasion success of exotic invaders in changing environments. However, if disadvantageous phenotypes are induced by plasticity, such plasticity may be detrimental to population fitness31,32.

In this study, we investigated the relationship between clonal plant invasiveness and environmental heterogeneity in a manipulative experiment. The correlation between clonal performance and the spatial distribution of soil was studied in a stoloniferous weed species that is a detrimental invasive in many regions worldwide, – Alternanthera philoxeroides. Three non-invasive wetland stoloniferous clonal plant species that co-occur with A. philoxeroides – a native congener Alternanthera sessilis, an exotic non-invasive Myriophyllum aquaticum and the native Jussiaea repens – were selected as comparison species to explore the invasion mechanism of A. philoxeroides in heterogeneous environments. Alternanthera philoxeroides competes with the three non-invasive counterparts as these four species occupy similar ecological niche in the field (personal observation). The following hypotheses were postulated: i. A. philoxeroides benefits from soil heterogeneity, and the benefit strength is patch-scale dependent. ii. Compared with the three non-invasive functional counterparts, the invasive A. philoxeroides displays some trait advantages in the presence of different soil distribution patterns.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Alternanthera philoxeroides (Martius) Grisebach

Alternanthera philoxeroides is a stoloniferous clonal herb with a strong dispersal ability in terrestrial, semi-aquatic and aquatic habitats33. This species commonly reproduces via regeneration from clonal fragments in China. Previous studies have found that phenotypic plasticity in its clonal characteristics rather than genetic differentiation helps explain its successful invasion in a wide range of habitats in China25,34,35.

Alternanthera sessilis (L.) R. Br

As a stoloniferous clonal herb with sexual reproduction, A. sessilis is mainly distributed in moist habitats such as swamps, wetlands and the edges of ditches and canals36.

Myriophyllum aquaticum (Vell.) Verdcourt

Originating from South America as A. philoxeroides, M. aquaticum survives in both aquatic and semi-aquatic habitats37. Asexual clonal propagation is its major reproductive mode in China38.

Jussiaea repens L

Jussiaea repens is a dominant native species occurring in sub-tropical and tropical regions in China39. Its capacity for forming dense mats makes it a noxious “channel blocker” in Europe40. Its strong stoloniferous clonality also facilitates its dispersal in moist environments.

Experimental design

On June 25, 2015, fifty clonal ramets sharing similar morphology (10-cm-long shoots with 6 leaves for A. philoxeroides, A. sessilis and J. repens and 10-cm-long shoots with approximately 14 leaf whorls for M. aquaticum) were collected of each species from mono-populations of each species in the riparian zone of Liangzi Lake (30°05′–30°18′N, 114°21′–114°39′E). All of the collected plant materials were pre-cultivated in sandy clay three times for approximately two months before the experiment set-up. Twenty-four morphologically identical plants without branches were then selected of each species. Six plants of each species were randomly selected and dried to determine the initial biomass. The eighteen remaining plants (height: approximately 15 cm; initial biomass: mean ± SE, 0.3042 ± 0.0112 g for A. philoxeroides, 0.3778 ± 0.0124 g for A. sessilis, 0.3603 ± 0.0127 g for M. aquaticum and 0.4652 ± 0.0193 g for J. repens) were selected for the experiment.

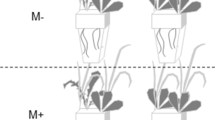

Seventy-two round basins (diameter: 45 cm, height: 45 cm) were selected as mesocosms. Three substrate types were designed: (1) homogeneous substrate (Ho), comprised of a homogenous mixture of equal volumes of clay (mean ± SE, five replicates, 0.055 ± 0.0063 g.g−1 organic matter; particle size: <75 μm) and sand (mean ± SE, five replicates, 0.004 ± 0.0004 g.g−1 organic matter, particle size: 330–880 μm); (2) heterogeneous substrate, composed of two contrasting patches of equal volumes of clay and sand (He1); and (3) heterogeneous substrate with six adjoining patches of equal volumes of clay and sand (He2) (Fig. 1). All of the substrates were 15 cm in thickness. The total amount of each resource type was identical across substrate types. All of the selected seedlings were cultivated into the centre of each substrate. Each treatment was replicated 6 times. All of the treatments and replicates were randomly positioned on an outdoor cement platform (10 mL × 10 mW). To produce a moist habitat, 1-cm-deep lake water (N:P = 0.71:0.04 mg.L−1) was maintained above the substrate surface throughout the experimental period. The experiment was established on August 30, 2015.

Schematic representation of the three substrate types with different soil distribution patterns.

Area in light grey represents mixture of same volume of clay and sand in Ho. Area in dark grey represents clay patch in He1 and He2. Area with slashes represents sand patch in He1 and He2. Central black points in Ho, He1 and He2 represent where the plant were cultivated during the experiment set-up

Harvest and measurement

All of the plant materials were harvested on November 25, 2015, after 87 days of growth. Immediately after harvest, stolon length was measured and ramet number was counted for each replicate. Five leaves of each replicate on the 3rd to 5th leaf node on the apical end of the stolon were selected to gauge leaf area (Li-3100 Area Meter, Li. Cor. Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska, USA) except for the leaves of M. aquaticum. As the leaves of M. aquaticum are tiny and needle-like, leaf area could not be precisely measured by the leaf area metre. Therefore, five leaves on the 5th to 7th leaf node on the apical end of the stolon were randomly selected and scanned (Epson V850 Perfection Pro, Seiko Epson Corp., Japan) to produce 1:1 high definition images (tiff format, 600 dpi) on a whiteboard with a ruler. Then, ImageJ 1.46 (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) was used to analyse the leaf area. The selected leaves of the four species were oven dried at 70 °C for 72 h to determine dry biomass. Specific leaf area (SLA) was calculated as follows41:

The mean SLA values of the selected five leaves of each replicate were used for data analysis.

The remnant parts of the plant materials were separated into leaves, stolon and roots (leaves, stolon, flowers and roots for A. sessilis) for each replicate. The biomass of each plant part in each replicate was determined after oven drying at 70 °C for 72 h. Total biomass, relative growth rate (RGR), leaf mass ratio (LMR), stolon mass ratio (SMR), root mass ratio (RMR) and root-shoot ratio (R/S ratio) were calculated as follows41:

Statistical analysis

All of the data met the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance prior to analysis. Stolon length, ramet number and total biomass were each transformed using the functions of log(log(x)), log(x) and log(x + 1), respectively. RGR, SMR and RMR were transformed using the square root(x) function. R/S ratio was transformed using the x1/4 function. Two-way ANOVA was implemented to test for the effects of species and substrate type on plant traits. If a significant treatment effect was detected, post hoc pair-wise comparisons of means were performed to examine differences between treatments using Duncan’s test for multiple comparisons. Dunnett’s test was used to examine the trait value differences between A. philoxeroides and each of the three non-invasive species. All of the analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

The species exerted significant effects on all traits, and the substrate type exerted significant effects on all traits except SLA (Table 1). Significant interactive effects of species and substrate type were observed on all traits except SLA, RMR and R/S ratio (Table 1).

Phenotypic variation

Alternanthera philoxeroides showed similar trait values of stolon length, SLA, total biomass, RGR, RMR and R/S ratio among the different substrates (Fig. 2a,c,d,e,h,i). Ramet number and LMR were 25.9% and 113.5% (significantly) higher and SMR was 8.2% (significantly) lower in the heterogeneous substrates than in Ho (Fig. 2b,f,g). No significant differences in ramet number, LMR and SMR of A. philoxeroides were shown between the He1 and He2 treatments (Fig. 2b,f,g). Alternanthera sessilis showed approximately the same responses as A. philoxeroides of all measured traits in the Ho, He1 and He2 treatments (Fig. 2).

Myriophyllum aquaticum showed 17.7% and 17.8% (significantly) lower values of stolon length and RGR, respectively, in the heterogeneous substrates than in Ho (Fig. 2a,e). Decreases of 37.6% and 42.4% in ramet number and total biomass, respectively, were observed between the Ho and He2 treatments (Fig. 2b,d). Similar values of SLA, biomass allocation and R/S ratio were observed among all substrates (Fig. 2c,f–i).

Jussiaea repens showed 9.8%, 13.8%, 30.7%, 12.6% and 9.9% (significantly) lower values of stolon length, ramet number, total biomass, RGR and SMR, respectively, in heterogeneous substrates than in Ho (Fig. 2a,b,d,e,g). SLA was homogeneous across all substrates (Fig. 2c). LMR was significantly higher by 42.8% in heterogeneous substrates than in Ho (Fig. 2f). Increases of 16.1% and 10.1% in RMR and R/S ratio, respectively, were shown in the He2 treatment relative to the Ho treatment, with significant differences observed between Ho and He2 (Fig. 2h,i).

Trait values

Alternanthera philoxeroides showed 41.8%, 58.9%, 44.9%, 45.1% and 27.0% (significantly) higher values of stolon length (P < 0.001), total biomass (P = 0.010), RGR (P < 0.001), RMR (P < 0.001) and R/S ratio (P < 0.001), respectively, than A. sessilis on average (Fig. 2a,d,e,h,i). Similar values of ramet number (P = 0.078) and LMR (P = 0.249) were shared between A. philoxeroides and A. sessilis on average (Fig. 2b,f). Alternanthera philoxeroides showed 11.3% and 9.52% (significantly) lower values of SLA (P = 0.014) and SMR (P < 0.001), respectively, than A. sessilis on average (Fig. 2c,g).

Alternanthera philoxeroides showed 12.8%, 19.9%, 31.5%, 10.5% and 70.9% (significantly) lower values of stolon length (P < 0.001), SLA (P < 0.001), total biomass (P = 0.001), RGR (P = 0.017) and LMR (P < 0.001), respectively, than M. aquaticum on average (Fig. 2a,c–f). Similar values of ramet number were shared between A. philoxeroides and M. aquaticum on average (P = 0.349) (Fig. 2b). Alternanthera philoxeroides showed 12.3%, 29.9% and 18.9% (significantly) higher values of SMR (P < 0.001), RMR (P < 0.001) and R/S ratio (P < 0.001), respectively, than M. aquaticum on average (Fig. 2g–i).

Alternanthera philoxeroides showed 28.4%, 45.0%, 10.2%, 57.9%, 24.2% and 49.6% (significantly) lower values of stolon length (P < 0.001), ramet number (P < 0.001), SLA (P = 0.033), total biomass (P < 0.001), RGR (P < 0.001) and LMR (P < 0.001), respectively, than J. repens on average (Fig. 2a–f). Similar values of SMR were shared between A. philoxeroides and J. repens on average (P = 0.299) (Fig. 2g). Alternanthera philoxeroides showed 13.5% and 9.2% (significantly) higher values of RMR (P = 0.002) and R/S ratio (P = 0.002), respectively, than J. repens on average (Fig. 2h,i).

Discussion

Soil heterogeneity may not be an optimal promoter of invasive performance in A. philoxeroides

Environmental heterogeneity is considered to favour clonal growth because stoloniferous clonal plants can display a variety of clonal functional traits that allow them to cope with environmental heterogeneity42. Clonal functional traits such as foraging behaviour, clonal integration and spatial division of labour are expected to benefit the performance of clonal plants in heterogeneous environments because they facilitate the exploitation of benign resources, internal exchange of resources and spread of risk9,10,11. Wijesinghe and Hutchings14,15 found a negative correlation between the performance (biomass) of the stoloniferous herb Glechoma hederacea and patch size. Moreover, Zhou et al.43 suggested that heterogeneity might be a significant driving factor of clonal plant invasion if a strong, positive response to fine-scale nutrient heterogeneity is common. In our study, based on our trait measurements, we found that A. philoxeroides gained some benefits from soil heterogeneity regardless of patch size. First, A. philoxeroides recruited more ramets in heterogeneous substrates than in the homogeneous substrate (Fig. 2b). As a low efficiency of sexual reproduction tends to exist in clonal plants44, clonal growth/reproduction is likely an important proxy of fitness in clonal plants45. A stronger recruitment of ramets may represent stronger propagule pressure related to the invasiveness potential of clonal invasive plants45. Second, a higher LMR and a lower SMR were simultaneously shown in heterogeneous environments relative to the homogeneous environment (Fig. 2f,g). This trade-off of biomass allocation might enable A. philoxeroides to invest more energy in light utilization rather than in the support structures in heterogeneous environments. The promotion of photosynthetic capacity might be induced by a “leafier” modular system46. These benefits derived from heterogeneity may confer A. philoxeroides with adaptive advantages under environmental heterogeneity.

However, our study found that A. philoxeroides displayed generally similar, scale-independent performance in most traits under different soil distribution patterns (Fig. 2a,c,d,e,h,i). A potential explanation for this result is that spatial division of labour, involving the integration of inter-connected clonal modules of A. philoxeroides, might help to effectively access the heterogeneous distribution of soil resources and buffer the soil heterogeneity10,22,47,48,49. Moreover, a long-term experimental study by Fransen and de Kroon50 showed that the extent to which environmental heterogeneity favours clonal plants weakens over time. Recently, Dong et al.51 showed that the performance of A. philoxeroides can be enhanced by clonal integration in homogeneous environments. Thus, the homogenization of plant performance in A. philoxeroides might be expected in heterogeneous environments. We predict that the benefit of environmental heterogeneity to clonal plants may be correlated with temporal scale.

In contrast to previous empirical findings14,15, A. philoxeroides benefited less from soil heterogeneity, and its performance was not patch-scale dependent. Environmental heterogeneity is unlikely to be a primary promoter of invasive success in A. philoxeroides.

Some advantageous traits of A. philoxeroides relative to those of its non-invasive functional counterparts contribute to its invasion success

An important invasion mechanism of successful invasive species is the ability of invasive species to outperform co-occurring non-invasive species in trait values and/or trait plasticity19,21,27,28,52. Advantageous trait values enable invasive species to outcompete non-invasive species and thus facilitate the establishment of invasive species in recipient habitats8,19. Adaptive trait plasticity promotes the optimal trait expression of invasive species in changing environments and thus enhances the ecological amplitude of invasive species when encountering a broad range of habitats23,25,29,30. In our study, we found that invasive A. philoxeroides possessed some advantages with respect to trait values and phenotypic variation compared with its non-invasive functional counterparts.

In terms of trait values, first, A. philoxeroides generally showed significantly higher trait values of stolon length, total biomass and RGR and significantly lower trait values of SMR in comparison with A. sessilis (Fig. 2a,d,e,g). As a proxy for habitat exploitation, stolon elongation is positively correlated with the capacity for dispersal and occupation in stoloniferous clonal plants53,54. The cost of stolon elongation for A. philoxeroides was lower than that for A. sessilis as A. philoxeroides invested less biomass into stolon elongation than did A. sessilis. A higher benefit/cost ratio may enable A. philoxeroides to rapidly colonize when competing with A. sessilis. Proxies for fitness commonly depend on biomass, size or growth rate19,55. Hence, higher biomass accumulation may reflect higher fitness for A. philoxeroides. Previous studies have suggested that RGR profoundly influences the competitive ability and recruitment of exotic invaders19,20,56. In the early phase of the invasion process, a higher RGR is likely an indicator of the more rapid establishment of exotic invaders in foreign habitats57. Second, A. philoxeroides generally showed significantly higher biomass allocation to roots than did the three non-invasive species (Fig. 2h,i). This higher root mass allocation may help A. philoxeroides to utilize soil nutrients more efficiently and/or enhance nutrient storage for asexual regeneration as storage roots are propagative organs in A. philoxeroides58,59. Previous studies have also demonstrated that successful invasive species likely benefit more from biomass allocation to belowground parts than do co-occurring non-invasive species, especially in infertile habitats19,52,57,60.

Overall, A. philoxeroides displayed significantly lower values of stolon length, SLA, total biomass, RGR and LMR than did M. aquaticum, and significantly lower values of stolon length, ramet number, SLA, total biomass, RGR and LMR than did J. repens on average (Fig. 2a–f). In terms of trait values, A. philoxeroides showed absolute inferiority in overall plant performance related to photosynthetic capacity and vegetative growth compared with M. aquaticum and J. repens19,20. However, A. philoxeroides displayed stronger adaptation to heterogeneity than did M. aquaticum and J. repens with respect to phenotypic variation. First, A. philoxeroides maintained approximately consistent values of stolon length, total biomass and RGR in all substrates and recruited more ramets in heterogeneous substrates than in the homogeneous one. In contrast, M. aquaticum and J. repens showed lower values of these traits under heterogeneity (Fig. 2a,b,d,e). Second, A. philoxeroides increased leaf mass allocation and decreased stolon mass allocation under heterogeneity, whereas M. aquaticum showed approximately identical biomass allocation in different substrates (Fig. 2f,g). Inconsistent with the hypothesis that environmental heterogeneity favours clonal plants over non-clonal ones12,61, both of the non-invasive clonal species M. aquaticum and J. repens showed unfavourable responses to environmental heterogeneity, whereas A. philoxeroides showed generally consistent performance across homogeneous and heterogeneous substrates. Our results are in partial agreement with a previous study by You et al.8 that found stronger clonal integration in A. philoxeroides than in J. repens in experimentally manipulated heterogeneous environments. Stronger clonality (e.g., clonal integration and spatial division of labour) in A. philoxeroides than in M. aquaticum and J. repens likely enabled A. philoxeroides to integrate the heterogeneity more efficiently and thus enhance its invasive potential. In contrast, the maladaptive trait plasticity shown by M. aquaticum and J. repens may confer fitness costs from an evolutionary perspective31,32.

In summary, soil heterogeneity is unlikely to be a primary promoter of invasive success in A. philoxeroides. This conclusion is based on our finding of approximately consistent performance maintenance across different soil distribution patterns. However, some advantages of A. philoxeroides over its non-invasive co-occurring functional counterparts with respect to trait values and phenotypic variation may help explain the successful invasion of the noxious clonal weed A. philoxeroides in heterogeneous environments. Additionally, based on our observations, we predict that soil texture, temporal scale and growing season are likely to influence the growth of the four evaluated species. Future studies should focus on how diversified environmental heterogeneity due to various ecological factors affects the invasive performance of clonal alien species.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, T. et al. The invasive stoloniferous clonal plant Alternanthera philoxeroides outperforms its co-occurring non-invasive functional counterparts in heterogeneous soil environments - invasion implications. Sci. Rep. 6, 38036; doi: 10.1038/srep38036 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Levine, J. M. Species diversity and biological invasions: relating local process to community pattern. Science 288, 852–854 (2000).

Jules, E. S., Kauffman, M. J., Ritts, W. D. & Carroll, A. L. Spread of an invasive pathogen over a variable landscape: a nonnative root rot on Port Orford cedar. Ecology 83, 3167–3181 (2002).

Miller, T. E., Kneitel, J. M. & Burns, J. H. Effect of community structure on invasion success and rate. Ecology 83, 898–905 (2002).

Davies, K. F. et al. Spatial heterogeneity explains the scale dependence of the native-exotic diversity relationships. Ecology 86, 1602–1610 (2005).

Pyšek, P. & Hulme, P. E. Spatio-temporal dynamics of plant invasions: linking pattern to process. Ecoscience 12, 302–315 (2005).

Kui, L., Li, F., Moore, G. & West, J. Can the riparian invader, Arundo donax, benefit from clonal integration? Weed Res. 53, 370–377 (2013).

You, W. H., Yu, D., Liu, C. H., Xie, D. & Xiong, W. Clonal integration facilitates invasiveness of the alien aquatic plant Myriophyllum aquaticum L. under heterogeneous water availability. Hydrobiologia 718, 27–39 (2013).

You, W. H., Fan, S. F., Yu, D., Xie, D. & Liu, C. H. An invasive clonal plant benefits from clonal integration more than a co-occurring native plant in nutrient patchy and competitive environments. PLoS ONE 9, e97246 (2014).

Stuefer, J. F., During, H. J. & de Kroon, H. High benefits of clonal integration in two stoloniferous species, in response to heterogeneous light environments. J. Ecol. 82, 511–518 (1994).

Stuefer, J. F., de Kroon, H. & During, H. J. Exploitation of environmental heterogeneity by spatial division of labour in a clonal plant. Funct. Ecol. 10, 328–334 (1996).

Yan, X., Wang, H. W., Wang, Q. F. & Rudstam, L. G. Risk spreading, habitat selection and division of biomass in a submerged clonal plant: Responses to heterogeneous copper pollution. Environ. Pollut. 174, 114–120 (2013).

Fischer, M. & van Kleunen, M. On the evolution of clonal plant life histories. Evol. Ecol. 15, 565–582 (2001).

Hutchings, M. J., Wijesinghe, D. K. & John, E. A. The effects of heterogeneous nutrient supply on plant performance: a survey of responses, with special reference to clonal herbs In The Ecological Consequences Of Environmental Heterogeneity: The 40th Symposium Of The British Ecological Society, Held At The University Of Sussex. 23–25 March 1999 (eds Hutchings, M. J., John, E. A. & Stewart, A. J. A. ) 91–110 (Blackwell Science Ltd, 2000).

Wijesinghe, D. K. & Hutchings, M. J. The effects of spatial scale of environmental heterogeneity on the growth of a clonal plant: an experimental study with Glechoma hederacea. J. Ecol. 85, 17–28 (1997).

Wijesinghe, D. K. & Hutchings, M. J. The effects of environmental heterogeneity on the performance of Glechoma hederacea: the interactions between patch contrast and patch scale. J. Ecol. 87, 860–872 (1999).

Melbourne, B. A. et al. Invasion in a heterogeneous world: resistance, coexistence or hostile takeover? Ecol. Lett. 10, 77–94 (2007).

Richards, C. L., Bossdorf, O., Muth, N. Z., Gurevitch, J. & Pigliucci, M. Jack of all trades, master of some? On the role of phenotypic plasticity in plant invasions. Ecol. Lett. 9, 981–993 (2006).

Drenovsky, R. E. et al. A functional trait perspective on plant invasion. Ann. Bot-London 110, 141–153 (2012).

van Kleunen, M., Weber, E. & Fischer, M. A meta-analysis of trait differences between invasive and non-invasive plant species. Ecol. Lett. 13, 235–245 (2010).

Pyšek, P. & Richardson, D. M. Chapter 7: Traits associated with invasiveness in alien plants: where do we stand? In Biological Invasions (ed. Nentwig, W. ) 97–125 (Springer-Verlag Berlin, 2007).

Caplan, J. S. & Yeakley, J. A. Functional morphology underlies performance differences among invasive and non-invasive ruderal Rubus species. Oecologia 173, 363–374 (2013).

Hutchings, M. J. & Wijesinghe, D. K. Patchy habitats, division of labour and growth dividends in clonal plants. Trends Ecol. Evol. 12, 390–394 (1997).

Pigliucci, M. Phenotypic Plasticity: Beyond Nature And Nurture. 1–28 (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

Geng, Y. P. et al. Phenotypic plasticity of invasive Alternanthera philoxeroides in relation to different water availability, compared to its native congener. Acta Oecol. 30, 380–385 (2006).

Geng, Y. P. et al. Phenotypic plasticity rather than locally adapted ecotypes allows the invasive alligator weed to colonize a wide range of habitats. Biol. Invasions 9, 245–256 (2007).

Hulme, P. E. Phenotypic plasticity and plant invasions: is it all Jack? Funct. Ecol. 22, 3–7 (2008).

Molina-Montenegro, M. A., Peñuelas, J., Munné-Bosch, S. & Sardans, J. Higher plasticity in ecophysiological traits enhances the performance and invasion success of Taraxacum officinale (dandelion) in alpine environments. Biol. Invasions 14, 21–33 (2012).

Hou, Y. P. et al. Fast-growing and poorly shade-tolerant invasive species may exhibit higher physiological but not morphological plasticity compared with non-invasive species. Biol. Invasions 17, 1555–1567 (2015).

Sultan, S. E. Phenotypic plasticity for fitness components in Polygonum species of contrasting ecological breadth. Ecology 82, 328–343 (2001).

Pohlman, C. L., Nicotra, A. B. & Murray, B. R. Geographic range size, seedling ecophysiology and phenotypic plasticity in Australian Acacia species. J. Biogeogr. 32, 341–351 (2005).

Langerhans, R. B. & DeWitt, T. J. Plasticity constrained: over-generalized induction cues cause maladaptive phenotypes. Evol. Ecol. Res. 4, 857–870 (2002).

Weinig, C. Differing selection in alternative competitive environments: shade-avoidance responses and germination timing. Evolution 54, 124–136 (2000).

Julien, M. H. & Bourne, A. S. Alligator weed is spreading in Australia. Plant Prot. Quart. 3, 91–96 (1988).

Wang, B. R., Li, W. G. & Wang, J. B. Genetic diversity of Alternanthera philoxeroides in China. Aquat. Bot. 81, 277–283 (2005).

Wang, N. et al. Clonal integration supports the expansion from terrestrial to aquatic environments of the amphibious stoloniferous herb Alternanthera philoxeroides. Plant Biology 11, 483–489 (2009).

Fan, S. F., Yu, D. & Liu, C. H. The invasive plant Alternanthera philoxeroides was suppressed more intensively than its native congener by a native generalist: implications for the biotic resistance hypothesis. PLoS ONE 8, e83619 (2013).

Hussner, A. & Champion, P. D. Chapter 9: Myriophyllum aquaticum (Vell.) Verdcourt (parrot feather) In A Handbook Of Global Freshwater Invasive Species (ed. Francis, R. A. ) 103–111 (Earthscan, 2012).

Xie, D., Yu, D., You, W. H. & Xia, C. X. The propagule supply, litter layers and canopy shade in the littoral community influence the establishment and growth of Myriophyllum aquaticum. Biol. Invasions 15, 113–123 (2013).

Li, M., Zhang, L. J., Tao, L. & Li, W. Ecophysiological responses of Jussiaea repens to cadmium exposure. Aquat. Bot. 88, 347–352 (2008).

Hussner, A. Alien aquatic plant species in European countries. Weed Res. 52, 297–306 (2012).

Pérez-Harguindeguy, N. et al. New handbook for standardised measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Aust. J. Bot. 61, 167–234 (2013).

Xie, X. F., Song, Y. B., Zhang, Y. L., Pan, X. & Dong, M. Phylogenetic meta-analysis of the functional traits of clonal plants foraging in changing environments. PLoS ONE 9, e107114 (2014).

Zhou, J. et al. Effects of soil nutrient heterogeneity on intraspecific competition in the invasive, clonal plant Alternanthera philoxeroides. Ann. Bot-London 109, 813–818 (2012).

Barrett, S. C. H., Eckert, C. G. & Husband, B. C. Evolutionary processes in aquatic plant populations. Aqua. Bot. 44, 105–145 (1993).

Xie, D. & Yu, D. Size-related auto-fragment production and carbohydrate storage in auto-fragment of Myriophyllum spicatum L. in response to sediment nutrient and plant density. Hydrobiologia 658, 221–231 (2011).

Lambers, H., Chapin, F. S. III & Pons, T. L. Plant Physiological Ecology. Second Edition 321–374 (Springer Science+Business Media, 2008).

Pitelka, L. F. & Ashmun, J. W. Physiology and integration of ramets in clonal plants In Population Biology And Evolution Of Clonal Organisms (eds Jackson, J. B. C., Buss, L. W. & Cook, R. E. ) 399–435 (Yale University Press, 1985).

Marshall, C. Source-sink relations of interconnected ramets In Clonal Growth In Plant: Regulation And Function (eds van Groenendael, J. & de Kroon, H. ) 23–41 (SPB Academic, 1990).

Hutchings, M. J. & de Kroon, H. Foraging in plants: the role of morphological plasticity in resource acquisition. Adv. Ecol. Res. 25, 159–238 (1994).

Fransen, B. & de Kroon, H. Long-term disadvantages of selective root placement: root proliferation and shoot biomass of two perennial grass species in a 2-year experiment. J. Ecol. 89, 711–722 (2001)

Dong, B. C., Alpert, P., Zhang, Q. & Yu, F. H. Clonal integration in homogeneous environments increases performance of Alternanthera philoxeroides. Oecologia 179, 393–403 (2015).

Funk, J. L. Differences in plasticity between invasive and native plants from a low resource environment. J. Ecol. 96, 1162–1173 (2008).

Bazzaz, F. A. Habitat selection in plants. Am. Nat. 137, 116–130 (1991).

Zobel, M., Moora, M. & Herben, T. Clonal mobility and its implications for spatio-temporal patterns of plant communities: what do we need to know next? Oikos 119, 802–806 (2010).

Hunt, J. & Hodgson, J. What is fitness, and how do we measure it? In Evolutionary Behavioral Ecology (eds Westneat, D. F. & Fox, C. W. ) 46–70 (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Dawson, W., Fischer, M. & van Kleunen, M. The maximum relative growth rate of common UK plant species is positively associated with their global invasiveness. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 20, 299–306 (2011).

Grotkopp, E. & Rejmánek, M. High seedling relative growth rate and specific leaf area are traits of invasive species: phylogenetically independent contrasts of woody angiosperms. Am. J. Bot. 94, 526–532 (2007).

Poorter, H. & Nagel, O. The role of biomass allocation in the growth response of plants to different levels of light, CO2, nutrients and water: a quantitative review. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 27, 595–607 (2000).

Schooler, S. S. Chapter 2: Alternanthera philoxeroides (Martius) Grisebach (alligator weed) In A Handbook Of Global Freshwater Invasive Species (ed. Francis, R. A. ) 25–35 (Earthscan, 2012).

Drenovsky, R. E., Martin, C. E., Falasco, M. R. & James, J. J. Variation in resource acquisition and utilization traits between native and invasive perennial forbs. Am. J. Bot. 95, 681–687 (2008).

Einsmann, J. C., Jones, R. H., Pu, M. & Mitchell, R. J. Nutrient foraging traits in 10 co-occurring plant species of contrasting life forms. J. Ecol. 87, 609–619 (1999).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge the Natural Science Foundation of China (31170339) and the Special Foundation of National Science and Technology Basic Research (2013FY112300). We also thank Hongwei Yu for his assistance in experiment set-up.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.W., D.Y. and C.H.L. designed the experiment. T.W., J.T.H. and L.L.M. carried out the experiment. T.W. and C.H.L. performed the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Hu, J., Miao, L. et al. The invasive stoloniferous clonal plant Alternanthera philoxeroides outperforms its co-occurring non-invasive functional counterparts in heterogeneous soil environments – invasion implications. Sci Rep 6, 38036 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38036

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38036

This article is cited by

-

Above- and belowground herbivory alters the outcome of intra- and interspecific competition between invasive and native Alternanthera species

Biological Invasions (2022)

-

Increasing soil heterogeneity strengthens the inhibition of a native woody plant by an invasive congener

Plant and Soil (2022)

-

Identify potential allelochemicals from Humulus scandens (Lour.) Merr. root extracts that induce allelopathy on Alternanthera philoxeroides (Mart.) Griseb.

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Highly competitive native aquatic species could suppress the growth of invasive aquatic species with similar traits

Biological Invasions (2021)

-

Moderate hydrological disturbance and high nutrient substrate enhance the performance of Myriophyllum aquaticum

Hydrobiologia (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.