Abstract

As in osmoregulation, mineralocorticoid signaling is implicated in the control of brain-behavior actions. Nevertheless, the understanding of this role is limited, partly due to the mortality of mineralocorticoid receptor (MR)-knockout (KO) mice due to impaired Na+ reabsorption. In teleost fish, a distinct mineralocorticoid system has only been identified recently. Here, we generated a constitutive MR-KO medaka as the first adult-viable MR-KO animal, since MR expression is modest in osmoregulatory organs but high in the brain of adult medaka as for most teleosts. Hyper- and hypo-osmoregulation were normal in MR-KO medaka. When we studied the behavioral phenotypes based on the central MR localization, however, MR-KO medaka failed to track moving dots despite having an increase in acceleration of swimming. These findings reinforce previous results showing a minor role for mineralocorticoid signaling in fish osmoregulation, and provide the first convincing evidence that MR is required for normal locomotor activity in response to visual motion stimuli, but not for the recognition of these stimuli per se. We suggest that MR potentially integrates brain-behavioral and visual responses, which might be a conserved function of mineralocorticoid signaling through vertebrates. Importantly, this fish model allows for the possible identification of novel aspects of mineralocorticoid signaling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corticosteroids have two major functions in vertebrates: a glucocorticoid function that affects metabolism and growth, and a mineralocorticoid function that regulates transport of ions and water. In many vertebrates, these functions are associated with two hormones, cortisol (or corticosterone in some species) and aldosterone, which activate the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), respectively.

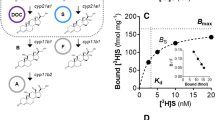

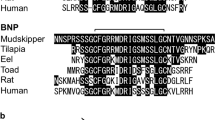

In teleost fish, it has long been held that a single hormone, cortisol, has both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid actions1, since fish lack aldosterone2,3. The counterparts of tetrapod MRs and their specific endogenous ligand, 11-deoxycorticosterone (DOC), have only recently been identified4,5,6,7. The effects of MR/GR agonists/antagonists and the dynamics of DOC/cortisol-MR/GR expressions indicate a minor role of mineralocorticoid signaling (DOC/cortisol-MR) in osmoregulation compared with that of glucocorticoid signaling (cortisol-GR)8. Thus, the function of the mineralocorticoid system in teleost fish has yet to be established.

In higher vertebrates, mineralocorticoid signaling is implicated in the control of physiological processes including brain-behavior actions, in addition to the osmoregulatory role9. However, understanding of this signaling is limited, partly due to the mortality of constitutive MR-knockout (KO) mice, resulting from impaired Na+ reabsorption at the distal tubules10,11, and the fact that a non-mouse MR-KO model has not been produced to date.

The mineralocorticoid system in fish may have biological actions in the brain and in behavior rather than in osmoregulation8,12,13,14, particularly in visuomotor performance, based on MR localization found in medaka (Oryzias latipes) in the present study. This fish is a useful model organism for studying these functions due to its tolerance to a wide range of salinities and several quantifiable behaviors. To better understand the role of MR, we generated the first MR-KO model, to our knowledge, in medaka using transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN) KO technology. Compared with wild-type (WT) fish, MR-KO medaka show normal adaptation to fresh water and seawater, but exhibit defects in locomotor activity guided by visual motion stimuli but not in recognition of these stimuli. Our results indicate that MR is required for behaviors affected by visual stimuli, but is not essential for osmoregulation in teleost fish. These results may reveal a phylogenetically conserved link between mineralocorticoid signaling and behavior.

Results

Predominant MR Expression in Brain and Eyes

To examine the function of the mineralocorticoid system in medaka, we first assessed the mr expression profile. In adult medaka, MR mRNA was detected at different levels in all eight tissues examined (Fig. 1a), with the highest levels in the brain and eyes, and the lowest in the gill, liver, and intestine. The detailed expression profiles are described in Fig. 1b and c, including the first thorough description of MR expression in the CNS of an ectothermic vertebrate. Regions of the medaka adult brain that exhibited higher concentrations of MR-immunoreactive (MRir) neuronal cell bodies corresponded to homologous regions of other vertebrate brains that contain MR12. Regions of intense MRir neuronal populations are emphasized; for other regions with fewer MRir neurons, see Fig. 1b. Dense populations of MRir neurons were observed in the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. Telencephalic regions exhibiting dense populations of MRir neurons included the ventral parts of the lateral zone of the dorsal telencephalon [Dl; putative teleostean homologue of the mammalian hippocampus15], and the commissural and subcommissural nuclei of the telencephalon [V; putative teleostean homologue to the mammalian amygdala15]. In the diencephalon, the hypothalamic preoptic area, inferior lobe of the hypothalamus, and the glomerulosus complex of the thalamus exhibited MRir neuronal cell bodies, as did the mesencephalic tegmentum and granular layer of the optic tectum. The cerebellum contained regions with prominent MRir neurons. These regions are shown in Fig. 1b. In the larval medaka head, brain had relatively dispersed MRir. Intense MRir was observed in most cells of the retina, predominantly in the nuclear and ganglion cell layers and choroid (Fig. 1c). Thus, the presence of MR-positive cells in regions that are important for visuomotor performance, including the dorsal part of the telencephalon, optic tectum (torus longitudinalis), cerebellum, and retina, is of particular interest16,17. There were no differences in expression between males and females.

Predominant MR Expression in Brain and Eyes.

(a) Expression of MR in tissues of adult (200 days post-fertilization) medaka determined by qPCR. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 5–8 in each group). Each fish was analyzed in triplicate. (b) Photomicrographs and schematics of frontal sections of the medaka telencephalon (b1), diencephalon (b2) and hindbrain (b3), showing relatively dense (stipples) regions of MRir neuronal cell bodies. (b2’) In situ hybridization of the consecutive section using mr mRNA probe, showing co-localization of the signal in MRir neurons. Abbreviations: CCe, corpus cerebelli; D, dorsal telencephalic area; Dl, lateral zone of D; Dm, medial zone of D; TeO, tectum opticum; TL, torus longitudinalis; V, ventral telencephalic area. Scale bar: 30 μm. (c) Frontal section of medaka larvae showing MRir regions (red) in the brain and retina with nuclear staining (blue, DAPI). The larvae at 7 dpf was analyzed, since MR transcripts continuously increased 4-fold between 3 and 7 dpf, and remained at this level at 9 dpf (immediately after hatch) during early development (Supplementary Fig. 1). Strong MRir signals were observed in the nuclear layer and ganglion cell layer of the retina, as well as the choroid. ONL, outer nuclear layer (photoreceptor layer); OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, retinal ganglion cell layer. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Generation and Identification of mr Mutant Alleles

Two TALEN arms were designed targeting exon 1 of the medaka mr gene, centered near the ATG start codon (Fig. 2). TALEN RNAs (25 pg left + 25 pg right) were injected into fertilized eggs at the 1 cell stage to produce mr mutant alleles. Bacterial clones of PCR-amplified genomic DNA isolated from 2–3 dpf TALEN-injected embryos revealed indel mutations in the target region, ranging from a 1 to 13 nucleotide deletion, but no insertion. Sibling embryos were raised to 2 months and screened individually by heteroduplex mobility assay (HMA) using fin biopsy genomic DNA, which identified 13 out of 68 fish carrying somatic indel mutations. These heterozygous carriers (XX females) were out-crossed with WT fish of an inbred strain, Hd-rR (XY), and offspring (F1) were raised at a reduced culturing density (6 fish per 1.8 L) to accelerate growth, and allow breeding as early as 2 months. A HMA of 1-month-old F1 fish revealed an average of 10% germline transmission of mutant alleles, with the same mutant allele present in all individuals derived from a single G0 parent. Deletion mutations of 2, 11 and 13 nucleotides were identified (Δ2, Δ11 and Δ13; Fig. 2). The Δ2 mutant alleles were identified first, and for this reason we focused on this line for subsequent analyses. DNA sequence genotyping showed that the mrΔ2 mutant allele generates a frameshift at amino acid #42, followed by a missense polypeptide of 7 amino acids that shows no significant similarity to any putative protein in the NCBI database. Wild-type medaka MR has 994 amino acids (108 kDa)18.

TALEN design and results of indel mutations in medaka mr.

Alignment of WT mr sequence with mutated PCR amplicons. A pair of TALEN was designed near the start ATG codon. The target sequences of the TAL effector DNA-binding domains are highlighted in red. Δ2, Δ11 and Δ13 alleles with 2–11- and 13-nucleotide deletions, respectively.

In F1 generation, all mrΔ2 heterozygous carriers turned out to be male. Δ2 males were crossed with Hd-rR females to obtain Δ2 females (F2), which were identified by RFLP genotyping. F2 Δ2 females were crossed with F1 Δ2 males to obtain a pool of offspring yielding the expected Mendelian proportion of homozygous and heterozygous mrΔ2 mutants, as determined by RFLP and DNA sequence genotyping. Juvenile mrΔ2 individuals were raised and in-crossed to obtain next-generation homozygous mutants, which were used for further experiments. We refer to these populations as MR-KO. Western blot analysis of total protein using the medaka MR antibody showed that MR was expressed in WT fish, but not in MR-KO fish, indicating that MR was successfully knocked out.

Normal Physical Characterization of MR-KO Medaka

MR-KO embryos, juveniles and sexually mature adults of medaka exhibited no signs of physical abnormalities, including in retinal cell layers assessed by gross anatomical measurements and hematoxylin and eosin staining histology. This is in contrast with MR-KO mice, in which mortality results from impaired osmoregulation. The muscle water content of MR-KO medaka was analyzed in fresh water and after seawater transfer (10 h and 1 week). Our previous study of seawater transfer showed a water loss from muscles of medaka by 2 h, followed by tissue rehydration to the original level by 10 h and normalized within 1 week19. Muscle water content in MR-KO adult medaka was normal compared with WT counterparts in fresh water and after seawater transfer (Fig. 3). Therefore, we conclude that, unlike in mammals, osmoregulation is normal in MR-KO medaka.

MR-KO Medaka have Abnormal Responses to Visual Motion Stimuli

Based on MR expression in medaka brain and eyes, responses of WT and MR-KO medaka to movements of black dots were recorded to test if MR-KO fish showed abnormal behavior (Fig. 4, Supplementary Video 1)20. The coordinates of the head of the fish were tracked in each video frame, and the distance from the head to the dot and acceleration were measured (Fig. 5). Before presentation of the moving dot, both WT and MR-KO fish swam moderately, with no detectable genotype difference (Fig. 5d; compare left upper and lower panels) after resuming normal swimming. When moving dots were presented, there were significant differences in the behavioral patterns of MR-KO and WT fish. The WT fish tracked the dot and the MR-KO fish showed inferior tracking ability. Thus, the distance to the dot for MR-KO fish was significantly greater than that for WT (Fig. 5c). Regarding acceleration during stimulus presentation, tracking by WT fish was smooth (Fig. 5d; right upper panel), whereas MR-KO fish showed jerky swimming episodes with bouts across the tank (Fig. 5d; right lower panel). During stimulation, a significant increase in acceleration from baseline was found only in MR-KO fish, and this increased acceleration was greater than that for WT fish (Fig. 5e). These results suggest that MR-KO medaka can recognize a stimulus, but that responses to the stimulus were abnormal.

Schematic of the experimental set-up for the behavioral test.

Stimuli were presented within an area of 615 × 72 pixels (170 × 20 mm2) located in the center of a 24-inch liquid-crystal display with a refresh rate of 60 Hz and resolution of 1,920 × 1080 pixels, and were controlled by computer software. The tip of the head of the fish and the dot was tracked using computer software. The distance to the dot and acceleration of the fish were analyzed.

Abnormal responses to visual motion stimuli in MR-KO medaka.

Naive fish were used in the behavioral test (n = 6). (a) Distance to the stimulus dot from the head and trajectory of a representative WT fish during stimulus presentation. (b) Distance to the dot from the head and trajectory of a representative MR-KO medaka during stimulus presentation. (c) Averaged distance from the head to the stimulus dot. (d) Acceleration during observation. The first 30 s at baseline (left) and the first 15 s and last 2.25 min of the stimulus presentation period (right) are not included. The WT fish (upper) swam at approximately constant speed, whereas the MR-KO fish (lower) swam in spurts during stimulus presentation. (e) Acceleration averaged during periods at baseline (before) and in stimulus presentation (after). The MR-KO fish swam significantly more than the WT fish during stimulus presentation, but the acceleration before stimulus presentation is similar in the two groups. Error bars show ± SEM.

Discussion

It is well-established that mineralocorticoid signaling is required for sodium homeostasis in mammals21, but the function in fish is unclear4,8. Studies using treatment with ligands, analysis of endogenous ligand-MR dynamics and knockdown of MR have led to somewhat contradictory results8,18,22,23,24,25. Loss-of-function and KO studies are currently lacking in non-mammalian models. Using TALEN technology, we generated the first constitutive MR-KO model in a vertebrate, and here we provide the first evidence that MR is required for normal behavior during exposure to visual motion stimuli, rather than for osmoregulation.

It is generally accepted that MRs in the mammalian brain are involved in physiological processes such as limbic system and hypothalamus pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis activities9,26. Behavioral results in mammals, however, are inconsistent, and hamper advancement in the field of mineralocorticoid signaling and actions. To date, these studies have relied heavily on a few mouse lines with conditionally altered MR expression or function27,28 (constitutive KO of MR is neonatal lethal in mouse), and tissue-restricted manipulations have incomplete or complex effects. Thus, it is critical to establish KO models with null alleles for MR genes and to study the effects on these processes. In homozygous MR-KO medaka, we observed defects in behavior during exposure to visual stimuli, and therefore we conclude that MR plays an essential role in these behaviors, and not in osmoregulation.

In osmoregulation in fish, cortisol acting via the GR may play a more important role than mineralocorticoid signaling8. Cortisol induces Na+ -K+-ATPase in Atlantic salmon and improves salinity tolerance via the GR, whereas DOC and aldosterone (which are ligands for teleost MR but not for GR) had no effect29. Also, Trayer et al.18 and Cruz et al.22 found that antisense knockdown of GR, but not of MR, downregulated differentiation of ionocytes in medaka and zebrafish. In our studies on the osmoregulatory esophagus of teleosts, cortisol appears to have a direct GR-dependent effect on differentiation of the esophageal epithelium during acclimation to different salinities, while DOC does not show any significant effects30,31. Furthermore, expression of GR mRNA is generally higher than that of MR mRNA in peripheral tissues, including osmoregulatory organs, but levels of MR and GR are similar in cichlid fish (Astatotilapia burtoni) and midshipman brain7,32. We (Fig. 1a) and Sturm et al.6 have examined many tissues in rainbow trout and medaka, and found that expression of MR mRNA is highest in brain and eyes. MR transcripts increase at hatch toward onset of visuomotor performance33 in the head (see Supplementary Fig. 1). The results in this study showing that MR-KO fish adapt to both fresh water and seawater provide clear evidence that MR is not required for osmoregulation in medaka.

Critical roles of MR in neuroendocrine functions, including stress, anxiety and cognition, have been shown in mammals using brain MR antagonists and in mouse with conditionally altered MR expression28,34. Blockade or KO of brain MR impairs memory and the HPA axis27,35,36,37,38,39,40,41, whereas transgenic MR overexpression in forebrain dampens anxiety-related behavior in mice26. In the current study, defects in behavior of MR-KO medaka during exposure to visual stimuli have been observed, possibly due to damage in vision and brain-dependent behavior, as described for a zebrafish gr mutant42,43. Such damage may modulate the neuroendocrine functions mentioned above, and thus our results may indicate a primarily conserved function of MR among vertebrates. Corticosteroids could integrate the HPA axis and limbic system with visual physiology of the sensory periphery, as part of a whole-organism coping mechanism that facilitates adjustment to rapid environmental changes, including visual stimuli. Our MR-KO medaka model thus provides a unique opportunity for identifying conserved networks regulated directly by MR in vertebrates.

The terms “glucocorticoid” and “mineralocorticoid” have their origin in mammalian studies. The results of this study showing essential MR function in brain-dependent behaviors of a teleost, and those of previous studies, suggest that these terms may be less appropriate, at least for teleost fish. The kidney action of mammalian mineralocorticoid signaling might have been acquired during evolution of the loop of Henle, a well-known mineralocorticoid target in mammals44, whereas brain-dependent behavioral function observed also in higher vertebrates may reflect the principal MR function through vertebrates. The evolution of the role of corticosteroids is intriguing. Since the MR is thought to be ancestral to the GR45,46, this principal function of MR may also reflect the original function of corticosteroid signaling.

Methods

Fish

The Hd-rR strain was used in the study. Handling and care was carried out using standard procedures47 in accordance with the Animal Research Guidelines at Okayama University. All procedures were approved by the Committee for Animal Research, Okayama University. All fish were raised and reared in aged tap water at 27 ± 2 °C with a 14:10 h light:dark cycle.

Gene Expression of mr by qRT-PCR

Total RNA from brain, eyes, gill, liver, kidney, intestine, testis and ovary of adult Hd-rR was extracted using a RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen). RNA quantity was determined by a Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen). Total RNA was reverse transcribed using the Omniscript RT Kit (Qiagen). qRT-PCR was performed using an ABI Prism 7000 (Applied Biosystems) and SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara)48,49. Standard operating conditions were 95 °C, 30 s, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 31 s. In each experiment, housekeeping genes RPL-7 (rpl7) were quantified concurrently. Gene-specific primers were designed [mr: 5′-CCA GAG GTG AAG GGT ATC CA-3′ and 5′-GAA GCC TCG TCT CCA CAA AC-3′; for rpl748]. The dissociation curves of the primer pairs showed a single peak. Relative standard curves were constructed for mr and rpl7 using cDNA stock from medaka RNA. The rpl7 mRNA level was relatively constant, as also shown previously48,49,50. Results for mr were normalized using rpl7 mRNA levels.

Localization of MR by Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization

Medaka adult brains and larvae at 7 dpf were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4 °C overnight, since MR transcripts continuously increased 4-fold between 3 and 7 dpf, and remained at this level at 9 dpf (immediately after hatch) during early development (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Fixed tissue samples were dehydrated through graded alcohol, embedded in paraffin wax, and serially sectioned at 8 μm. Frontal sections were placed on MAS-GP coated slides. Brains and larvae were subjected to immunostaining by the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (ABC) method51 using Vectastain ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and to fluorescent immunostaining, respectively, as described before31,52,53. The slides were subjected to heat-induced antigen retrieval by heating at 90 °C in target retrieval solution for 20 min (Dako). Subsequently, sections were washed in 0.3% Triton-X in PBS (PBST) and placed in a solution containing 1% normal goat serum and 1% BSA in PBST at room temperature for 30 min to block non-specific binding. Sections were incubated at 4 °C for 2 days with MR antiserum (1:2000). This antibody was raised against a peptide specific for the A/B domain of medaka MR (DSKDNNSNKQEQPRLQL; Medical & Biological Laboratories, Japan), which shares low sequence identity (<20%) with other steroid receptors2,18. Pre-absorption of the antibody with the antigen peptide completely prevented staining in immunohistochemistry. Furthermore, cellular localization of the immunoreactive MR correlated with the respective cellular expression of the mr gene identified by in situ hybridization carried out using the DIG-labeled antisense riboprobes (Fig. 1b2) as described54. Images were captured with an Olympus FSX100 fluorescent microscope. The MR antibody specificity was also confirmed by performing western blots on protein extracts from brains55.

Design and Generation of TALENs

TALEN reagents used in this study were designed and constructed by Transposagen. Briefly, candidate TALEN target sequences in the medaka mr gene retrieved from the Ensemble medaka genomic database (http://www.ensembl.org/Oryzias_latipes/index.html) were identified, and from these we selected one near the start methionine codon to achieve maximal disruption of the mr coding sequence (see Fig. 2 for positions and target sequences). Initial validation tests for cleavage activity were performed on episomal target sequences in vitro by Transposagen.

For expression in medaka embryos, TALEN RNAs were synthesized in vitro using a mMessage mMachine T7 Ultra kit (Life Technologies) and injected into Hd-rR embryos. TALEN mRNAs (25 pg of each arm: the dosage giving the highest indel mutation efficiency and <50% morphological toxicity at 24 hpf) were injected at the 1-cell stage. To detect indel mutations in the TALEN target region, HMA was performed56,57,58. Crude extracts of genomic DNA were prepared from medaka embryos at 2–3 dpf using KAPA Express Extract (Nippon Genetics). 1 μL of this crude extract was used as template for subsequent PCR. A 264-bp amplicon flanking the TALEN target region was amplified with the primer pair (forward 5′-TGT CCA GCC CTC ACA GTA TG-3′; reverse 5′-GGC TGC TGC TAT CGT TCT G-3′58 using Emerald Amp PCR Master Mix (Takara) in a Thermal Cycler (BioRad). The reaction profile consisted of polymerase activation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, with final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The resulting amplicons were analyzed using discontinuous polyacrylamide gels with a 4% stacking gel and a 9% separating gel for the HMA. When a heteroduplex polymorphism was observed, the PCR amplicon was cloned into the pMD-20 vector using a Mighty TA cloning kit (Takara) and sequenced (Macrogen).

Genotype Analysis by RFLP

Genomic DNA from tail fin biopsies or whole embryos was prepared and the region containing the target site of the TALEN was amplified, as described above. The resulting PCR products that were cloned and sequenced for verification were digested at 37 °C for 30 min in 20 μL of DdeI restriction digestion solution that consisted of reaction buffer and 2 units of DdeI (New England Biolabs). The 264 bp PCR product was cut to yield 126 bp and 138 bp fragments for only WT alleles. These digestion products were analyzed using agarose gels.

Analysis of Osmoregulation

Muscle water content was used as an indicator of osmoregulatory capacity because it is difficult to collect blood from small medaka. In many teleost species, including medaka, changes in muscle water content are inversely related to changes in plasma osmolality, sodium and chloride19,59,60,61,62,63. Adult medaka in fresh water (0 ppt) were transferred to fresh water or seawater in the morning (0–1 h after light onset; 0700–800 h). After 10 h and 1 week transfer to seawater, the caudal portion of the paraxial muscle was dissected out. Samples of muscle were immediately weighed. Dry weights were obtained after drying at 100 °C until constant weight was attained (24 h), and the water content was expressed as a percentage of the wet weight.

Behavioral Tests and Image Analysis

Plastic aquaria attached to the LCD (U2410, Dell) (Fig. 4) were used for the behavioral test. To limit visual stimulation, the lateral sides were covered with white polystyrene sheets. The test tanks were filled with housing water (water depth 11.0 cm) maintained at a 27 ± 1 °C by air conditioning. To the test aquarium, a fish which was naive to the aquarium and randomly selected from the WT or MR-KO group was individually transferred. Eighteen hours later, the LCD was attached to the tank and the animal was allowed to habituate for 15 min. The behavioral test consisted of a baseline period (1 min) and a stimulus presentation period (3 min). Illumination was adjusted with white florescent lamps on the ceiling. After the habituation period, the behavior of the fish was recorded for 3.5 min. All behavioral testing was restricted to the early afternoon (6–9 h after light onset; 1300–1600 h). The first 1 min of recording was used to determine the baseline activity, in which no stimuli were presented. Visual motion stimuli were presented on the LCD during the last 3 min (stimulus presentation period). The stimuli were animations of a zigzagging black dot (1 mm in diameter) on a white background, controlled by a program written in LabVIEW 8 (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) running on a Windows PC. Stimuli were presented as 3-min animations constituting six repetitions of the same 30-sec animation (Fig. 4, Supplementary Video 1). This design was used because preliminary studies showed that recognition/tracking by WT medaka was maximized at this speed and decreased at faster (2 and 1.5 times) and slower (0.5 and 0.25 times) speeds.

Movies were recorded at a frame rate of 30 fps with a digital camera (HandyCam, Sony Electronics) and saved on the hard disk. Offline analysis of the original sequence (all frames) was carried out with video analysis software (Tracker ver. 4.86, http://physlets.org/tracker/). Coordinates of the head of the fish were tracked in each video frame (Fig. 5a,b) and the distance from the head to the dot was measured. The trajectory of the fish was graphed over time and evaluated with respect to acceleration (Fig. 5d). Due to the dimensional limits, the behavior was assessed using two-dimensional coordinates from the side view.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was carried out with Statview 5.0 (Abacus Concepts) using one-, two- or three-way analysis of variance, followed by appropriate post-hoc tests. Data were checked for normality and equal variances.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Sakamoto, T. et al. Principal function of mineralocorticoid signaling suggested by constitutive knockout of the mineralocorticoid receptor in medaka fish. Sci. Rep. 6, 37991; doi: 10.1038/srep37991 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Wendelaar Bonga, S. E. The stress response in fish. Physiol Rev 77, 591–625 (1997).

Prunet, P., Sturm, A. & Milla, S. Multiple corticosteroid receptors in fish: from old ideas to new concepts. Gen Comp Endocrinol 147, 17–23 (2006).

Bury, N. R. & Sturm, A. Evolution of the corticosteroid receptor signalling pathway in fish. Gen Comp Endocrinol 153, 47–56 (2007).

Gilmour, K. M. Mineralocorticoid receptors and hormones: fishing for answers. Endocrinology 146, 44–46 (2005).

Baker, M. E. Evolution of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid responses: go fish. Endocrinology 144, 4223–4225 (2003).

Sturm, A. et al. 11-deoxycorticosterone is a potent agonist of the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) mineralocorticoid receptor. Endocrinology 146, 47–55 (2005).

Greenwood, A. K. et al. Multiple corticosteroid receptors in a teleost fish: distinct sequences, expression patterns, and transcriptional activities. Endocrinology 144, 4226–4236 (2003).

Takahashi, H. & Sakamoto, T. The role of ‘mineralocorticoids’ in teleost fish: relative importance of glucocorticoid signaling in the osmoregulation and ‘central’ actions of mineralocorticoid receptor. Gen Comp Endocrinol 181, 223–228 (2013).

Losel, R. M. & Wehling, M. Classic versus non-classic receptors for nongenomic mineralocorticoid responses: emerging evidence. Front Neuroendocrinol 29, 258–267 (2008).

Gass, P., Reichardt, H. M., Strekalova, T., Henn, F. & Tronche, F. Mice with targeted mutations of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors: models for depression and anxiety? Physiol Behav 73, 811–825 (2001).

Sakamoto, H. et al. Rapid signaling of steroid hormones in the vertebrate nervous system. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 17, 996–1019 (2012).

Stolte, E. H. et al. Corticosteroid receptors involved in stress regulation in common carp, Cyprinus carpio. J Endocrinol 198, 403–417 (2008).

Schjolden, J., Basic, D. & Winberg, S. Aggression in rainbow trout is inhibited by both MR and GR antagonists. Physiol Behav 98, 625–630 (2009).

Sakamoto, T. et al. Corticosteroids stimulate the amphibious behavior in mudskipper: potential role of mineralocorticoid receptors in teleost fish. Physiol Behav 104, 923–928, doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.06.002 (2011).

Northcutt, R. & Davis, R. Telencephalic organization in ray-finned fishes. Fish neurobiology 2, 203–236 (1983).

Nieuwenhuys, R. An Overview of the Organization of the Brain of Actinopterygian Fishes. Am. Zool. 22, 287–310 (1982).

Ito, H. & Vanegas, H. Visual receptive thalamopetal neurons in the optic tectum of teleosts (Holocentridae). Brain Res 290, 201–210 (1984).

Trayer, V., Hwang, P. P., Prunet, P. & Thermes, V. Assessment of the role of cortisol and corticosteroid receptors in epidermal ionocyte development in the medaka (Oryzias latipes) embryos. Gen Comp Endocrinol, doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.09.011 (2013).

Sakamoto, T., Kozaka, T., Takahashi, A., Kawauchi, H. & Ando, M. Medaka (Oryzias latipes) as a model for hypoosmoregulation of euryhaline fishes. Aquaculture 193, 347–354 (2001).

Nakayasu, T. & Watanabe, E. Biological motion stimuli are attractive to medaka fish. Anim Cogn 17, 559–575, doi: 10.1007/s10071-013-0687-y (2014).

Morris, D. J., Latif, S. A. & Brem, A. S. Interactions of mineralocorticoids and glucocorticoids in epithelial target tissues revisited. Steroids 74, 1–6 (2009).

Cruz, S. A., Lin, C. H., Chao, P. L. & Hwang, P. P. Glucocorticoid receptor, but not mineralocorticoid receptor, mediates cortisol regulation of epidermal ionocyte development and ion transport in zebrafish (danio rerio). PLoS One 8, e77997 (2013).

Mathieu, C., Milla, S., Mandiki, S. N., Douxfils, J. & Kestemont, P. In vivo response of some immune and endocrine variables to LPS in Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis, L.) and modulation of this response by two corticosteroids, cortisol and 11-deoxycorticosterone. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 167, 25–34 (2014).

O’Connor, C. M., Rodela, T. M., Mileva, V. R., Balshine, S. & Gilmour, K. M. Corticosteroid receptor gene expression is related to sex and social behaviour in a social fish. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 164, 438–446 (2013).

Mathieu, C. et al. First evidence of the possible implication of the 11-deoxycorticosterone (DOC) in immune activity of Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis, L.): comparison with cortisol. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 165, 149–158 (2013).

Rozeboom, A. M., Akil, H. & Seasholtz, A. F. Mineralocorticoid receptor overexpression in forebrain decreases anxiety-like behavior and alters the stress response in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 4688–4693 (2007).

Berger, S. et al. Loss of the limbic mineralocorticoid receptor impairs behavioral plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 195–200 (2006).

Kolber, B. J., Wieczorek, L. & Muglia, L. J. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation and behavioral analysis of mouse mutants with altered glucocorticoid or mineralocorticoid receptor function. Stress 11, 321–338 (2008).

McCormick, S. D., Regish, A., O’Dea, M. F. & Shrimpton, J. M. Are we missing a mineralocorticoid in teleost fish? Effects of cortisol, deoxycorticosterone and aldosterone on osmoregulation, gill Na+.K+-ATPase activity and isoform mRNA levels in Atlantic salmon. Gen Comp Endocrinol 157, 35–40 (2008).

Takagi, C., Takahashi, H., Kudose, H., Kato, K. & Sakamoto, T. Dual in vitro effects of cortisol on cell turnover in the medaka esophagus via the glucocorticoid receptor. Life Sci 88, 239–245, doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.11.017 (2011).

Takahashi, H., Takahashi, A. & Sakamoto, T. In vivo effects of thyroid hormone, corticosteroids and prolactin on cell proliferation and apoptosis in the anterior intestine of the euryhaline mudskipper (Periophthalmus modestus). Life Sci 79, 1873–1880 (2006).

Arterbery, A. S., Deitcher, D. L. & Bass, A. H. Corticosteroid receptor expression in a teleost fish that displays alternative male reproductive tactics. Gen Comp Endocrinol 165, 83–90 (2010).

Alsop, D. & Vijayan, M. M. Development of the corticosteroid stress axis and receptor expression in zebrafish. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294, R711–719, doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00671.2007 (2008).

de Kloet, E. R. et al. Brain mineralocorticoid receptors and centrally regulated functions. Kidney Int 57, 1329–1336 (2000).

Oitzl, M. S. & de Kloet, E. R. Selective corticosteroid antagonists modulate specific aspects of spatial orientation learning. Behav Neurosci 106, 62–71 (1992).

Souza, R. R., Dal Bo, S., de Kloet, E. R., Oitzl, M. S. & Carobrez, A. P. Paradoxical mineralocorticoid receptor-mediated effect in fear memory encoding and expression of rats submitted to an olfactory fear conditioning task. Neuropharmacology 79, 201–211 (2014).

Schwabe, L., Tegenthoff, M., Hoffken, O. & Wolf, O. T. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade prevents stress-induced modulation of multiple memory systems in the human brain. Biol Psychiatry 74, 801–808 (2013).

Conrad, C. D., Lupien, S. J., Thanasoulis, L. C. & McEwen, B. S. The effects of type I and type II corticosteroid receptor agonists on exploratory behavior and spatial memory in the Y-maze. Brain Res 759, 76–83 (1997).

Douma, B. R. et al. Repeated blockade of mineralocorticoid receptors, but not of glucocorticoid receptors impairs food rewarded spatial learning. Psychoneuroendocrinology 23, 33–44 (1998).

Yau, J. L., Noble, J. & Seckl, J. R. Continuous blockade of brain mineralocorticoid receptors impairs spatial learning in rats. Neurosci Lett 277, 45–48 (1999).

Ratka, A., Sutanto, W., Bloemers, M. & de Kloet, E. R. On the role of brain mineralocorticoid (type I) and glucocorticoid (type II) receptors in neuroendocrine regulation. Neuroendocrinology 50, 117–123 (1989).

Muto, A., Taylor, M. R., Suzawa, M., Korenbrot, J. I. & Baier, H. Glucocorticoid receptor activity regulates light adaptation in the zebrafish retina. Front Neural Circuits 7, 145, doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00145 (2013).

Ziv, L. et al. An affective disorder in zebrafish with mutation of the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Psychiatry 18, 681–691 (2013).

Dietl, P., Good, D. & Stanton, B. Adrenal corticosteroid action on the thick ascending limb. Semin Nephrol 10, 350–364 (1990).

Baker, M. E., Funder, J. W. & Kattoula, S. R. Evolution of hormone selectivity in glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 137, 57–70 (2013).

Baker, M. E., Chandsawangbhuwana, C. & Ollikainen, N. Structural analysis of the evolution of steroid specificity in the mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors. BMC Evol Biol 7, 24 (2007).

Iwamatsu, T. Stages of normal development in the medaka Oryzias latipes. Mech Dev 121, 605–618 (2004).

Ogoshi, M. et al. Growth, energetics and the cortisol-hepatic glucocorticoid receptor axis of medaka (Oryzias latipes) in various salinities. Gen Comp Endocrinol, doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.05.001 (2012).

Ogoshi, M., Kato, K. & Sakamoto, T. Effect of environmental salinity on expression of adrenomedullin genes suggests osmoregulatory activity in the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Zoological Letters 1, 12 (2015).

Zhang, Z. & Hu, J. Development and validation of endogenous reference genes for expression profiling of medaka (Oryzias latipes) exposed to endocrine disrupting chemicals by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Toxicol. Sci. 95, 356 (2007).

Hsu, S. M., Raine, L. & Fanger, H. Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: a comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem 29, 577–580 (1981).

Takahashi, H. et al. Prolactin receptor and proliferating/apoptotic cells in esophagus of the Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) in fresh water and in seawater. Gen Comp Endocrinol 152, 326–331 (2007).

Sakamoto, T. et al. Neurohypophysial hormones regulate amphibious behaviour in the mudskipper goby. PLoS One 10, e0134605 (2015).

Paul-Prasanth, B. et al. Estrogen oversees the maintenance of the female genetic program in terminally differentiated gonochorists. Sci Rep 3, 2862 (2013).

Satoh, K. et al. In vivo processing and release into the circulation of GFP fusion protein in arginine vasopressin enhanced GFP transgenic rats: response to osmotic stimulation. FEBS J 282, 2488–2499, doi: 10.1111/febs.13291 (2015).

Ansai, S. et al. Design, evaluation, and screening methods for efficient targeted mutagenesis with transcription activator-like effector nucleases in medaka. Dev Growth Differ 56, 98–107, doi: 10.1111/dgd.12104 (2014).

Chen, J. et al. Efficient detection, quantification and enrichment of subtle allelic alterations. DNA Res 19, 423–433 (2012).

Ota, S. et al. Efficient identification of TALEN-mediated genome modifications using heteroduplex mobility assays. Genes Cells 18, 450–458, doi: 10.1111/gtc.12050 (2013).

Kang, C. K., Tsai, S. C., Lee, T. H. & Hwang, P. P. Differential expression of branchial Na + /K(+)-ATPase of two medaka species, Oryzias latipes and Oryzias dancena, with different salinity tolerances acclimated to fresh water, brackish water and seawater. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 151, 566–575 (2008).

Kelly, S. P., Chow, I. N. & Woo, N. Y. Effects of prolactin and growth hormone on strategies of hypoosmotic adaptation in a marine teleost, Sparus sarba. Gen Comp Endocrinol 113, 9–22 (1999).

Jensen, M. K., Madsen, S. S. & Kristiansen, K. Osmoregulation and salinity effects on the expression and activity of Na +,K(+)-ATPase in the gills of European sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.). J Exp Zool 282, 290–300 (1998).

Madsen, S. S. Enhanced hypoosmoregulatory response to growth hormone after cortisol treatment in immature rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri. Fish Physiol Biochem 8, 271–279, doi: 10.1007/BF00003422 (1990).

Madsen, S. S. The role of cortisol and growth hormone in seawater adaptation and development of hypoosmoregulatory mechanisms in sea trout parr (Salmo trutta trutta). Gen Comp Endocrinol 79, 1–11 (1990).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Andre P. Seale for critically reading this manuscript. This work was supported by JSPS Grant 15H04395.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S., M.Ys. and H.T. designed the research. M.Ys., H.T. and T.I. performed the experiments. T.S., M.Ys., H.T. and H.S. analysed the data. T.S., M.Ys., H.T., T.I., Y.O., T.N., N.K., K.M. and H.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sakamoto, T., Yoshiki, M., Takahashi, H. et al. Principal function of mineralocorticoid signaling suggested by constitutive knockout of the mineralocorticoid receptor in medaka fish. Sci Rep 6, 37991 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37991

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37991

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of the effects of exogenous cortisol manipulation and the glucocorticoid antagonist, RU486, on the exploratory tendency of bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus)

Fish Physiology and Biochemistry (2023)

-

The mineralocorticoid receptor is essential for stress axis regulation in zebrafish larvae

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Characterization and Expression Dynamics of Key Genes Involved in the Gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata) Cortisol Stress Response during Early Ontogeny

Marine Biotechnology (2018)

-

The mineralocorticoid receptor knockout in medaka is further validated by glucocorticoid receptor compensation

Scientific Data (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.