Abstract

Motifs of planar metalloborophenes, cage-like metalloborospherenes, and metal-centered double-ring tubular boron species have been reported. Based on extensive first-principles theory calculations, we present herein the possibility of doping the quasi-planar C2v B56 (A-1) with an alkaline-earth metal to produce the penta-ring tubular Ca©B56 (B-1) which is the most stable isomer of the system obtained and can be viewed as the embryo of metal-doped (4,0) boron α-nanotube Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-1). Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-1) can be constructed by rolling up the most stable boron α-sheet and is predicted to be metallic in nature. Detailed bonding analyses show that the highly stable planar C2v B56 (A-1) is the boron analog of circumbiphenyl (C38H16) in π-bonding, while the 3D aromatic C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) possesses a perfect delocalized π system over the σ-skeleton on the tube surface. The IR and Raman spectra of C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) and photoelectron spectrum of its monoanion C4v Ca©B56− are computationally simulated to facilitate their spectroscopic characterizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well known that boron has a strong propensity to form multicenter-two-electron bonds (mc-2e bonds) to compensate for its electron deficiency in both polyhedral molecules and bulk allotropes. Multicenter bonding also appears to dominate the planar or quasi-planar structures of a wide range of gas-phase boron clusters Bn−/0 (n = 3–25, 27, 30, 35, 36) characterized in a series of combined experimental and theoretical investigations in the past decade1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Both the quasi-planar C6v B36−/0 7,8 with a perfect hexagonal hole at the center and the perfect planar C2v Co©B18− with a hepta-coordinate Co were confirmed experimentally to be motifs of the atomically thin planar borophenes and metalloborophenes, respectively. In these flat species, periphery boron atoms are bonded with localized 2c–2e σ bonds along the boundary, while the inner and the periphery atoms are sewed together in blocks with delocalized mc-2e σ or π bonds. Multicenter bonding interactions go extremes from two-dimensional (2D) sheets to three-dimensional (3D) cages in the recently observed borospherenes (all-boron fullerenes) D2d B40−/0 14, C3/C2 B39− 15, and C2 B28−/0 16 in which all the valence electrons are distributed in delocalized mc-2e σ or π bonds (m ≥ 3). Both endohedral M@B40 (M = Ca, Sr) and exohedral M&B40 (M=Be, Mg) metalloborospherenes were predicted to be stable species17. Two cage-like cations C1 B41+ and C2 B422+ predicted at density functional theory (DFT) have also been presented to the Bnq borospherene family (q = n-40) which are all composed of twelve interwoven boron double chains (BDCs) with six hexagonal or heptagonal faces18. Encapsulations of alkaline earth or transition metals have proven to be an effective approach to stabilize borospherene anions like Th B364− in Li2&[Ca@B36]19, Cs B373− in Ca@B37− 20, Cs B382− in Ca@B38 21 and M@B38 (M = Sc, Y, Ti)21,22, and C3/C2 B39− in Ca@B39+ 23. The discovery of the first double-ring (DR) tubular B20 and the experimental confirmation of the double-ring (DR) tubular Bn+ monocations (n = 16–25)24, on the other hand, unveils another important domain in the structural evolution of boron clusters. The recent experimental observation of the metal-centered DR tubular D8d Co©B16− with the coordination of 16 further indicate that doping boron clusters with a transition metal makes an earlier structural transition from 2D planar to 3D tubular in boron clusters25. Triple-ring (TR) tubular B3n (n = 8–32) have also been predicted to be competitive isomers at DFT26. Very recently, a penta-ring (PR) tubular α-B84 with six evenly distributed hexagonal holes in the middle was predicted to be the second lowest-lying isomer of the system at DFT27. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no PR tubular boron clusters or their metal complexes as the lowest-lying isomers of the systems reported to date. Detailed investigations on the geometrical and electronic structures of multi-ring tubular clusters and their metal-centered complexes may provide key information to understand the geometrical structures and growth mechanisms of the experimentally observed single-walled and multi-walled boron nanotubes (BNTs)28,29 and the atomically thin borophenes with or without vacancies deposited on Ag(111) substrates30,31.

Based upon extensive first-principles theory calculations, we present herein the possibility of doping the previously predicted quasi-planar B56 (A-1)27 with an alkaline earth metal to produce the charge-transfer PR tubular complex Ca©B56 (B-1) which is the most stable isomer of the system obtained and can be viewed as the embryo of metal-doped boron α-nanotube Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-1) in a bottom-up approach. Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-1) can be constructed by rolling up the most stable boron α-sheet32,33 and is predicted to be metallic in nature. Detailed molecular orbital analyses show that the quasi-planar C2v B56 (A-1) is analogous to circumbiphenyl (C38H16) in π bonding, while the PR tubular C4v Ca2+©B562− (B-1) possesses a perfect delocalized π system over a σ-skeleton on the tube surface to render tubular aromaticity to the system. The IR, Raman, and photoelectron spectra of the concerned species are simulated to facilitate their experimental characterizations.

Results and Discussions

We start from the bared B56 which may serve as effective ligands to coordinate metal dopants. As shown in Fig. 1(a) and Fig. S1(a), the previously predicted quasi-planar C2v B56 (A-1) with two equivalent hexagonal holes27 appears to be 1.05 eV and 1.06 eV more stable than the quasi-planar C1 B56 (A-2) with three hexagonal holes around the center and the PR tubular C2h α-B56 (A-3) with four equivalent hexagonal holes in the middle at PBE0 level, respectively. Other low-lying isomers lie at least 1.19 eV above B56 (A-1), with the much concerned cage-like borospherene C2 B56 (A-7) composed of eighteen interwoven BDCs14,15,19,20,21,23 and the irregular cage-like C1 B56 (A-9) obtained using first-principles simulated annealing34 being 1.78 eV and 2.64 eV less stable, respectively. With two extra electrons, a quasi-planar C2v B562− similar to B56 (A-1) appears to be 1.07 eV more stable than the PR tubular D4h α-B562− similar to α-B56 (A-3) at PBE0.

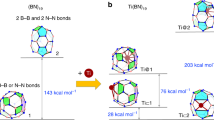

With one doping Ca atom added in to compensate for the electron deficiency of the system, surprisingly, a dramatic structural transition occurs from the 2D quasi-planar C2v B56 (A-1) to 3D PR tubular C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) which has a Ca cap at one end of the tube along the four-fold molecular axis, as demonstrated in Fig. 1(b) and Fig. S1(b). Ca©B56 (B-1) contains an almost perfect PR tubular C4v α-B56 ligand similar to α-B56 (A-3) which can be constructed by rolling up the most stable boron α-sheet32,33. From another perspective of view, Ca©B56 (B-1) can be viewed as a PR tube composed of interwoven BDCs with four hexagonal holes evenly distributed in the middle, in a structural pattern similar to that of the Bnq borospherene family (q = n-40, n = 36–42)14,15,19,20,21,23. C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) turns out to lie 1.18 eV and 1.71 eV lower than the Ca-centered PR tubular D4h Ca©B56 (B-2) based on α-B56 (A-3) and the face-capped quasi-planar Cs CaB56 (B-3) based on C2v B56 (A-1), respectively. Other low-lying planar, tubular, or cage-like isomers appear to be at least 1.82 eV less stable than Ca©B56 (B-1), with the endohedral metalloborospherenes S4 Ca@B56 (B-6) based on B56 (A-7) and C1 Ca@B56 (B-13) based on B56 (A-9) lying 1.87 eV and 2.29 eV higher, respectively. These large relative energies provide strong evidence that Ca©B56 (B-1) is the first PR tubular species as the most stable isomer of the system obtained to date. We notice that C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) possesses two small degenerate imaginary vibrational frequencies at 38.5i cm−1 at PBE0 (e modes) which lead to the slightly distorted PR tubular Cs Ca©B56 (B-4) when fully relaxed. However, the energy difference between C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) and Cs Ca©B56 (B-4) turns out to be only 0.01 eV with zero-point corrections included, strongly suggesting that they correspond to the same tubular isomer possible to exist in experiments, given the accuracy of the DFT-PBE0 method employed. Ca©B56 (B-1) is thus the vibrationally averaged structure of PR tubular CaB56, with the Ca atom slightly off-centered circling around the molecular axis of the PR tube on the top.

Such a structural transition from 2D planar to 3D PR tubular also occurs to SrB56 at PBE0 (see Fig. S2, the Stuttgart relativistic small-core pseudopotential and valence basis set was used for Sr35,36). Natural bonding orbital (NBO) analyses indicate that the PR tubular C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) and C4v Sr©B56 possess the natural atomic charges of qCa = +1.83|e| and qSr = +1.85|e| and the corresponding electronic configurations of Ca[Ar]4s0.073d0.09 and Sr[Kr]5s0.064d0.07, respectively. They are therefore typical charge-transfer complexes C4v Ca2+©B562− (B-1) and C4v Sr2+©B562− in nature in which the alkaline earth metal donates two ns2 valence electrons to the PR tubular α-B56 acceptor. Such complexes are mainly stabilized by effective electrostatic interactions between the M2+ dication (M = Ca, Sr) and the PR tubular α-B562− ligand. Weak π→d back donations from the α-B562− ligand to the M2+ metal center may also contribute to stabilize the complexes, as suggested by the electronic configurations mentioned above, similar to the situation in M@B40 (M = Ca, Sr)17.

Extensive molecular dynamics simulations using the CP2K program37 indicate that Ca©B56 (B-1) is dynamically stable at both 600 K and 800 K, with the root-mean-square-deviations of RMSD = 0.18 Å and 0.18 Å and the maximum bond length deviations of MAXD = 1.10 Å and 1.13 Å, respectively (Fig. S3). We notice that, although the tubular α-B56 ligand experiences more or less structural deformations during MD simulations, the Ca cap in Ca©B56 (B-1) keeps almost still at the center of the top B12 ring in the simulation processes. MD simulations indicate that Ca©B56 (B-1) remains dynamically stable even at 1000 K, with RMSD = 0.19 Å and MAXD = 1.14 Å, respectively, further indicating its high dynamical stability.

The high stability of planar C2v B56 (A-1) originates from its electronic structure and bonding pattern. As analyzed in Fig. 2 using the adaptive natural density partitioning (AdNDP) approach38, C2v B56 (A-1) possesses 24 2c-2e localized σ bonds between neighboring periphery B atoms along the boundary, 12 3c-2e delocalized σ bonds on 12 B3 triangles around the two hexagonal holes, and 29 4c-2e delocalized σ bonds on 29 symmetrically distributed B4 rhombuses. The remaining 19 π bonds can be classified into four sets, with one set with 6 4c-2e π bonds and 2 5c-2e π bonds along the periphery, two sets with 3 12c-2e π bonds over the hexagonal hole on the right and 3 12c-2e π bonds over the hexagonal hole on the left, and one set with 5 56c-2e π bonds over the whole molecular surface, in the overall symmetry of C2v. C2v B56 (A-1) thus contains two local π-aromatic systems around the two hexagonal holes and one global π-aromatic system over the whole molecular plane which have a one-to-one correspondence with the aromatic π-systems of circumbiphenyl (C38H16) (see Fig. 2). It is therefore the boron analog of D2h C38H16, the biggest boron analog of aromatic polycyclic hydrocarbon reported to date1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

The bonding pattern of PR tubular Ca©B56 (B-1) is more unique and intriguing. As shown in Fig. 3, it has 24 2c-2e localized σ bonds between neighboring periphery boron atoms on the top and bottom of the tube with the occupation numbers of ON = 1.76–1.84 |e|, 40 3c-2e delocalized σ bonds on the 40 inner B3 triangles with ON = 1.74–1.96 |e|, and 4 4c-2e delocalized σ bonds in the middle on the four uncovered B4 rhombuses between neighboring hexagonal holes with ON = 1.78 |e|. The σ-skeleton on the tube surface thus contains 68 σ bonds in total. The remaining 34 valence electrons form a perfectly delocalized π system over the delocalized σ-skeleton, with 16 5c–2e π bonds evenly distributed over two B24 DR tubular subunits at the two ends of the tube with ON = 1.72–1.80 |e| and 1 32c-2e π bond over the four evenly distributed hexagonal holes between the two subunits with ON = 1.77 |e|, in the overall symmetry of C4v. As shown in Fig. 3, the bared PR tubular D4h α-B562− dianion possesses the same σ and π bonding patterns as C4v Ca©B56 (B-1), further supporting the charge transfer of two 4 s electrons from Ca atom to the tubular α-B56 ligand. The AdNDP bonding patterns of C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) and D4hα-B562− with ON ≥ 1.72 |e| match the chemical intuitions for tubular boron clusters which can be constructed by rolling up the α-sheet32,33. Such bonding patterns render 3D tubular aromaticities to the systems, as evidenced by the huge negative NICS values of −44.6 ppm and −46.0 ppm at the tube centers calculated for C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) and D4h α-B562−, respectively.

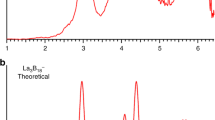

The IR and Raman spectra of C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) are computationally simulated and compared with that of the perfect PR tubular D4h α-B562− in Fig. 4 to facilitate its future spectroscopic characterization. As expected, the major IR peaks at 1249 cm−1 (a2u mode), 1117 cm−1 (a2u), 1025 cm−1 (eu), and 866 cm−1 (a2u) in D4h α-B562− are all basically maintained in C4v Ca©B56 (B-1). The major Raman features at 1248 cm−1 (a1g), 1013 cm−1 (a1g), 897 cm−1 (a1g), 806 cm−1 (eg), and 386 cm−1 (a1g) in D4h α-B562− also appear in C4v Ca©B56 (B-1). The breathing modes at 236 cm−1 (a1) in C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) and 244 cm−1 (a1g) in D4h α-B562− belong to typical “radial breathing modes” (RBMs) of the tubular species which may help characterize metal-centered boron α-nanotubes in future experiments. A strong RBM band observed at 210 cm−1 was used to identify the hollow structures of the single-walled boron nanotubes28.

Combination of the PES spectra and first-principles theory calculations has proven to be the most powerful approach to characterize novel boron clusters over the past decade1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,25. We calculate the vertical excitation energies and simulate the PES spectra of the corresponding monoanions of C2v B56 (A-1) and C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) at PBE0 level in Fig. 5. As shown in Fig. 5(a), quasi-planar C2v B56−, the monoanion of C2v B56 (A-1), possesses a high first vertical detachment energy of VDE = 3.76 eV and a simulated PES spectrum similar to that of the observed quasi-planar Cs B40− which has the first VDE of 3.60 eV14. PR tubular C4v Ca©B56−, the monoanion of C4v Ca©B56 (B-1), appears to possess a PES spectrum with a low VDE of 3.07 eV and a large energy gap of 0.89 eV (Fig. 6(b)), in line with the large HOMO-LUMO energy gap of 2.00 eV calculated for tubular Ca©B56 (B-1) at PBE0.

Finally, using C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) as an embryo at the center of the unit cell, we construct the metal-doped (4,0) boron α-nanotube Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-1) in a bottom-up approach which has a P4 symmetry as shown in Fig. 6(a). A similar approach was used to predict the nanotubes of silicon39. Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-1) turns out to possess the optimized diameter of 6.55 Å and the lattice parameter of c = 8.72 Å in z direction (Fig. 6(a)). Interestingly, as indicated in its calculated band structures in Fig. 6(b), with several bands crossing the Fermi level, Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-1) is predicted to be typically metallic in nature, in strong contrast to the bared α-boron nanotube BNT(4,0) which is a semiconductor with the band gap of 0.69 eV at PBE level (Fig. S4) (0.75 eV at GGA33), indicating that the transport properties of boron nanotubes can be dramatically changed by metal-doping. It is noticed that the slightly off-centered Ca-doped boron α-nanotube Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-2) with P1 symmetry (Fig. 6(c)) possesses a total energy slightly lower than Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-1) (by 0.22 eV per unit cell). However, the two metallic Ca-doped boron α-nanotube with slightly different geometries (Fig. 6(a and c)) possess very similar band structures (Fig. 6(b and d)), indicating that minor changes in positions of the metal donors cause no obvious changes in both the geometries and conductivities of metal-doped boron α-nanotubes.

In summary, we have performed in this work an extensive first-principles theory investigation on the possibility of doping the quasi-planar C2v B56 (A-1) with an alkaline-earth metal to produce the 3D aromatic PR tubular Ca©B56 (B-1) which is the most stable isomer obtained and can be viewed as the embryo of the metal-doped boron α-nanotube Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-1). The high stability of the 3D aromatic C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) originates from its unique bonding pattern which possesses a perfect delocalized π system over a σ-skeleton on the tube surface. Metal dopants encapsulated in cage-like borospherenes to form metalloborospherenes17,19,20,21,22,23, inserted in planar borophenes to form metalloborophenes9, or wrapped up in boron nanotubes to form metal-doped boron nanotubes may effectively enhance the chemical stabilities and tune the transport properties of the boron nanostructures. Metal-stabilized boron nanostructures are expected to be complementary with the corresponding carbon nanomaterials in applications and warrant further theoretical and experimental investigations.

Theoretical procedures

Initial structures were constructed for CaB56 based on the previously reported lowest-lying planar or cage-like isomers of B5627,34. Cage-like borospherene structures composed of interwoven BDCs were also built for B56 according to the structural pattern of borospherenes14,15,19,20,21,23. In particular, a PR tubular α-B56 (A-2) with four hexagonal holes evenly distributed in the middle was constructed by rolling up the most stable boron α-sheet32,33. Low-lying isomers thus obtained were then fully optimized with frequencies checked at the hybrid DFT-PBE040 level with the basis set of 6–311+G(d)41 implemented in Gaussian 09 suite42. Minima Hopping43 searches with over 500 stationary points probed produced no isomers with lower energies than Ca©B56 (B-1) (see Fig.1 and S1(b)). The bonding patterns of the quasi-planar C2v B56 (A-1) (Fig. 2) and PR tubular C4v Ca©B56 (B-1) (Fig. 3) were analyzed using the AdNDP method which is an extension of the Lewis valence bond theory to include multicenter mc-2e interactions (m ≥ 3)38 and has been successfully applied to various systems8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,23,25. The photoelectron spectroscopy (PES) of the quasi-planar C2v B56− and PR tubular C4v Ca©B56− were simulated using the time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT-PBE0) approach44. The metal-centered α-boron nanotube Ca©BNT(4,0) (C-1) constructed by rolling up the most stable boron α-sheet32,33 was optimized using Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)45,46 at Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)47 level with the projector augmented wave (PAW)48,49 pseudopotential method. The nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS)50 values at the tube centers of Ca©B56 (B-1) and D4h B562− were calculated to assess their tubular aromaticities.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tian, W.-J. et al. From Quasi-Planar B56 to Penta-Ring Tubular Ca©B56: Prediction of Metal-Stabilized Ca©B56 as the Embryo of Metal-Doped Boron α-Nanotubes. Sci. Rep. 6, 37893; doi: 10.1038/srep37893 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Zhai, H.-J., Alexandrova, A. N., Birch, K. A., Boldyrev, A. I. & Wang, L.-S. Hepta- and octacoordinate boron in molecular wheels of eight- and nine-atom boron clusters: Observation and confirmation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 6004–6008 (2003).

Zhai, H.-J., Kiran, B., Li, J. & Wang, L.-S. Hydrocarbon analogues of boron clusters-planarity, aromaticity and antiaromaticity. Nat. Mater. 2, 827–833 (2003).

Kiran, B. et al. Planar-to-tubular structural transition in boron clusters: B20 as the embryo of single-walled boron nanotubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 961–964 (2005).

Huang, W. et al. A concentric planar doubly π-aromatic B19− cluster. Nat. Chem. 2, 202–206 (2010).

Li, W.-L., Zhao, Y.-F., Hu, H.-S., Li, J. & Wang, L.-S. [B30]−: a quasi-planar chiral boron cluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 5540–5545 (2014).

Li, W.-L. et al. The B35 cluster with a double-hexagonal vacancy: a new and more flexible structural motif for borophene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 12257–12260 (2014).

Piazza, Z. A. et al. Planar hexagonal B36 as a potential basis for extended single-atom layer boron sheets. Nat. Commun. 5, 3113 (2014).

Chen, Q. et al. Quasi-planar aromatic B36 and B36− clusters: all-boron analogues of coronene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 18282–18287 (2014).

Li, W.-L. et al. The Planar CoB18− Cluster as a Motif for Metallo-Borophenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 7358–7363 (2016).

Alexandrova, A. N., Boldyrev, A. I., Zhai, H.-J. & Wang, L.-S. All-boron aromatic clusters as potential new inorganic ligands and building blocks in chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 250, 2811–2866 (2006).

Romanescu, C., Galeev, T. R., Li, W.-L., Boldyrev, A. I. & Wang, L.-S. Transition-Metal-Centered Monocyclic Boron Wheel Clusters (M©Bn): A New Class of Aromatic Borometallic Compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 350–358 (2013).

Sergeeva, A. P. et al. Understanding Boron through Size-Selected Clusters: Structure, Chemical Bonding, and Fluxionality. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 1349–1358 (2014).

Wang, L.-S. Photoelectron spectroscopy of size-selected boron clusters: from planar structures to borophenes and borospherenes. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 35, 69–142 (2016).

Zhai, H.-J. et al. Observation of an all-boron fullerene. Nat. Chem. 6, 727–731 (2014).

Chen, Q. et al. Experimental and theoretical evidence of an axially chiral borospherene. ACS Nano 9, 754–760 (2015).

Wang, Y. J. et al. Observation and characterization of the smallest borospherene, B28− and B28 . J. Chem. Phys. 144, 064307 (2016).

Bai, H., Chen, Q., Zhai, H.-J. & Li, S.-D. Endohedral and exohedral metalloborospherenes: M@B40 (M=Ca, Sr) and M&B40 (M=Be, Mg). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 941–945 (2015).

Chen, Q. et al. Cage-like B41+ and B422+: New chiral members of the borospherene family. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 941–945 (2015).

Tian, W.-J. et al. Saturn-like charge-transfer complexes Li4&B36, Li5&B36+, and Li6&B362+: exohedral metalloborospherenes with a perfect cage-like B364− core. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 9922–9926 (2016).

Chen, Q. et al. Endohedral charge-transfer complex Ca@B37−: stabilization of a B373− borospherene trianion by metal-encapsulation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 14186–14190 (2016).

Chen, Q. et al. Endohedral Ca@B38: stabilization of a B382− borospherene dianion by metal encapsulation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 11610–11615 (2016).

Lu, Q.-L., Luo, Q.-Q., Li, Y.-D. & Huang, S.-G. DFT study on endohedral and exohedral B38 fullerenes: M@B38 (M = Sc, Y, Ti) and M&B38 (M = Nb, Fe, Co, Ni). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 20897–20902 (2015).

Chen, Q. et al. Endohedral C3 Ca@B39+ and C2 Ca@B39+: axially chiral metalloborospherenes based on B39−. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 19690–19694 (2015).

Oger, E. et al. Boron cluster cations: transition from planar to cylindrical structures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 8503–8506 (2007).

Popov, I. A., Jian, T., Lopez, G. V., Boldyrev, A. I. & Wang, L.-S. Cobalt-centred boron molecular drums with the highest coordination number in the CoB16− cluster. Nat. Commun. 6, 8654 (2015).

Tian, F.-Y. & Wang, Y.-X. The competition of double-, four-, and three-ring tubular B3n (n = 8–32) nanoclusters. J. Chem. Phys. 129, 024903 (2008).

Rahane, A. B. & Kumar, V. B84: a quasi-planar boron cluster stabilized with hexagonal holes. Nanoscale 7, 4055–4062 (2015).

Ciuparu, D., Klie, R. F., Zhu, Y. & Pfefferle, L. Synthesis of Pure Boron Single-Wall Nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 3967–3969 (2004).

Liu, F. et al. Metal-like single crystalline boron nanotubes: synthesis and in situ study on electric transport and field emission properties. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 2197–2205 (2010).

Mannix, A. J. et al. Synthesis of borophenes: anisotropic, two-dimensional boron polymorphs. Science 350, 1513–1516 (2015).

Feng, B.-J. et al. Experimental realization of two-dimensional boron sheets. Nat. Chem. 8, 563–568 (2016).

Tang, H. & Ismail-Beigi, S. Novel Precursors for Boron Nanotubes: The Competition of Two-Center and Three-Center Bonding in Boron Sheets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 115501 (2007).

Yang, X.-B., Ding, Y. & Ni, J. Ab initio prediction of stable boron sheets and boron nanotubes: Structure, stability, and electronic properties. Phys. Rev. B 77, 041402 (2008).

Wang, L., Zhao, J.-J., Li, F.-Y. & Chen, Z.-F. Boron fullerenes with 32–56 atoms: Irregular cage configurations and electronic properties. Chem. Phys. Lett. 501, 16–19 (2010).

Feller, D. The role of databases in support of computational chemistry calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 17, 1571–1586 (1996).

Schuchardt, K. L. et al. Basis Set Exchange: A Community Database for Computational Sciences. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 47, 1045–1052 (2007).

VandeVondele, J. et al. Quickstep: Fast and accurate density functional calculations using a mixed Gaussian and plane waves approach. Comput. Phys. Commun. 167, 103–128 (2005).

Zubarev, D. Y. & Boldyrev, A. I. Developing paradigms of chemical bonding: adaptive natural density partitioning. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 5207–5217 (2008).

Singh, A. K., Kumar, V., Briere, T. M. & Kawazoe, Y. Cluster assembled metal encapsulated thin nanotubes of silicon. Nano Lett. 2, 1243–1248 (2002).

Adamo, C. & Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 6158–6170 (1999).

Krishnan, R., Binkley, J. S., Seeger, R. & Pople, J. A. Self‐consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 650–654 (1980).

M. J. Frisch, et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01, Gaussian Inc., Wallingford, CT (2009).

Goedecker, S., Hellmann, W. & Lenosky, T. Global minimum determination of the Born-Oppenheimer surface within density functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 055501 (2005).

Bauernschmitt, R. & Ahlrichs, R. Treatment of electronic excitations within the adiabatic approximation of time dependent density functional theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 256, 454–464 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Norm-conserving and ultrasoft pseudopotentials for first-row and transition elements. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 6, 8245–8257 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Schleyer, P. v. R., Maerker, C., Dransfeld, A., Jiao, H.-J. & Hommes, N. J. R. v. E. Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts: A Simple and Efficient Aromaticity Probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 6317–6318 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21373130, 11504213, and 21473106).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-D. Li, Y.-W. Mu, and H.-G. Lu conceived and designed the work. W.-J. Tian, Q. Chen, and X.-X. Tian performed the calculations and analyzed the results. All the authors analyzed the data, discussed the results and made comments on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, WJ., Chen, Q., Tian, XX. et al. From Quasi-Planar B56 to Penta-Ring Tubular Ca©B56: Prediction of Metal-Stabilized Ca©B56 as the Embryo of Metal-Doped Boron α-Nanotubes. Sci Rep 6, 37893 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37893

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37893

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.