Abstract

Mycobacterium avium complex induces macrophage apoptosis. However, the M. avium components that inhibit or trigger apoptosis and their regulating mechanisms remain unclear. We recently identified the immunodominant MAV2054 protein by fractionating M. avium culture filtrate protein by multistep chromatography; this protein showed strong immuno-reactivity in M. avium complex pulmonary disease and in patients with tuberculosis. Here, we investigated the biological effects of MAV2054 on murine macrophages. Recombinant MAV2054 induced caspase-dependent macrophage apoptosis. Enhanced reactive oxygen species production and JNK activation were essential for MAV2054-mediated apoptosis and MAV2054-induced interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production. MAV2054 was targeted to the mitochondrial compartment of macrophages treated with MAV2054 and infected with M. avium. Dissipation of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm) and depletion of cytochrome c also occurred in MAV2054-treated macrophages. Apoptotic response, reactive oxygen species production, and ΔΨm collapse were significantly increased in bone marrow-derived macrophages infected with Mycobacterium smegmatis expressing MAV2054, compared to that in M. smegmatis control. Furthermore, MAV2054 expression suppressed intracellular growth of M. smegmatis and increased the survival rate of M. smegmatis-infected mice. Thus, MAV2054 induces apoptosis via a mitochondrial pathway in macrophages, which may be an innate cellular response to limit intracellular M. avium multiplication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), a member of the nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) group, is an opportunistic pathogen in humans and animals1 and is the most common cause of NTM lung disease worldwide2. MAC causes severe pulmonary and disseminated disease in immunocompromised hosts, particularly in individuals with AIDS3,4. MAC can also cause lung disease in apparently immunocompetent patients without underlying lung disease5. Although the diagnoses of disease due to NTM has increased worldwide in recent years6, little is known about the pathogenesis and virulent mechanism of NTM including MAC, particularly the detailed interactions between host cells and the bacteria.

Mycobacteria are intracellular facultative pathogens that grow within macrophages, which constitute the first line of innate immunity against most mycobacteria7,8. Therefore, mycobacterial virulence depends on the ability of these bacteria to invade, persist, and replicate within the hostile environment of macrophages. Apoptosis of macrophages infected with mycobacteria occurs during the disease course, and most studies have indicated that this is an innate cellular response to limit the multiplication of intracellular pathogens9,10. Most reports have indicated that apoptosis induction by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is inversely proportional to bacterial virulence11,12. MAC-infected macrophages also undergo apoptosis through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), and mitochondrial death signalling13 or tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and Fas14. Apoptosis of M. avium-infected macrophages limit bacterial viability, suggesting that apoptosis acts as a defence mechanism against this pathogen15. In contrast, another report indicated that MAC can survive in apoptotic macrophages and that many of the bacteria escape the dying cells and infect adjacent macrophages16. The exact role of macrophage apoptosis in MAC infection remains unclear.

Programmed cell death is emerging as a major effect of bacterial pathogenesis. Virulent M. tuberculosis doses inhibit host cell apoptosis, while also inducing pro-apoptotic signals. To improve the understanding of the cellular mechanisms of mycobacterial pathogenesis, it is important to identify and characterise the bacterial components involved in modulating macrophage apoptosis. Several apoptosis-inducing factors of M. tuberculosis have been identified: 19-kDa protein12,17 and lipoarabinomannan18 via Toll-like receptor 2, PE_PGRS33 with TNF-α-inducing ability19, 38-kDa protein with up-regulation of cell death receptor20, and heparin-binding hemagglutinin (HBHA) via mitochondrial targeting9. The sonic extracts from M. avium cause apoptosis of monocytes and macrophages21, indicating that MAC also contains a component involved in modulating apoptosis. Recently, we identified M. avium MAV2052 protein, which induced apoptosis in murine macrophages22. However, the MAC components involved in inhibiting or triggering apoptosis are not well-understood.

To identify valuable antigens in the complex mycobacterial antigen mixture, we fractionated the mycobacterial culture filtrate proteins by multistep chromatography and determined the immunoreactivty of each fraction23,24,25. Recently, we identified MAV2054 protein with strong immuno-reactivity in MAC pulmonary disease as well as in patients with tuberculosis by fractionation of M. avium culture filtrate proteins26. At the amino acid level, MAV2054 protein shares 100% homology with the 35-kDa major membrane protein 1 of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Mycobacterium leprae major membrane protein, an immunodominant protein27, shows 92% identity with MAV2054. In this study, we investigated the biological effects of MAV2054 on macrophages. MAV2054 induced significant apoptosis in macrophages through the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, and the release of cytochrome c, and MAV2054 was efficiently targeted to the mitochondria of macrophages. Furthermore, M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 increased macrophage apoptosis in vivo and in vitro, its growth within macrophages was suppressed, and MAV2054 expression attenuated the virulence of M. smegmatis.

Results

MAV2054 induces caspase-dependent macrophage apoptosis

Since M. avium MAV2054 is a major membrane protein and an immunodominant antigen26,27, we first determined whether MAV2054 could induce macrophage activation. Incubation with MAV2054 converted RAW264.7 cells into differentiated macrophage-like cells at an early stage, but cell death patterns morphologically appeared after 24 h. We tested whether MAV2054 induced apoptosis using a cell death ELISA kit to assess DNA fragmentation. MAV2054 induced significant apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 1A). We used native antigen 85 complex (Ag85) as an unrelated mycobacterial control protein. Ag85 is the major secreted and fibronectin-binding protein of M. tuberculosis, and shows strong immunoreactivity28,29. Apoptosis was significantly greater in cells treated with MAV2054 as compared to untreated control or cells treated with Ag85 (Fig. 1B). In addition, based on the results from MTT assay, it appeared that MAV2054 induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner but not antigen 85 complex (Ag85) or LPS (Supplementary Figure 1a). MAV2054-induced cell death did not occur because of necrosis because lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was not detected in the culture supernatant of cells treated with MAV2054 (Supplementary Figure 1b). Flow cytometry results revealed that the population of Annexin-V-positive cells in MAV2054-treated RAW264.7 cells was significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). Staurosporine (STS) was used as a positive control. Similar results were observed in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (Fig. 1D). However, neither LPS nor Ag85 induced significant apoptosis in BMDMs. We further assessed whether MAV2054 induced macrophage apoptosis in a caspase-dependent manner. As shown in Fig. 1E, cleavage of caspase-3, caspase-9, and poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) in cells treated with MAV2054 for 24 h was observed and was comparable to that in STS-treated cells. In addition, MAV2054 induced the activation of caspase-8. Inhibition of caspases by a pan-caspase inhibitor, z-VAD-fmk, attenuated MAV2054-induced DNA fragmentation (Fig. 1F). Overall, these data support that MAV2054 caused caspase-dependent apoptosis in macrophages.

MAV2054 induces caspase-dependent macrophage apoptosis.

(A,B) DNA fragmentation of RAW264.7 cells incubated with the indicated concentrations of MAV2054 or Ag85 for 24 h was measured by Cell Death Detection ELISA. Values represent the mean OD405 ± SD of at least three experiments. (C,D) Apoptosis of RAW264.7 cells treated with MAV2054 (1, 5, 10 μg/mL), Ag85 (10 μg/mL), or STS (50 nM) for 24 h was measured by flow cytometry using Annexin V/PI staining. Flow cytometric histograms are representative mean ± SD of three independent experiments (E) Total lysate from RAW264.7 cells exposed to each antigen for 24 h were immunoblotted against caspase 3, caspase 9, caspase 8, and PARP. To confirm equal protein loading, blots were re-probed with an antibody against β-actin. (F) RAW264.7 cells were incubated with MAV2054 (10 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of zVAD-fmk (50 μM). DNA fragmentation was measured as described above. Results are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 for antigen treatments compared to untreated cells (medium control, MC).

MAV2054 induces production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines

TNF-α and IL-6 are pro-inflammatory cytokines that participate in macrophage activation and regulate the cell death pathway during infection30,31,32. We tested whether MAV2054 could stimulate a macrophage to secrete these cytokines. RAW264.7 cells or BMDMs treated with MAV2054 produced significant TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 compared to untreated controls or Ag85 (Fig. 2). Although endotoxin content was continuously monitored during preparation of the recombinant protein, we further assessed LPS contamination by treatment with proteinase K or heat denaturation, which abrogated the ability of MAV2054 to stimulate macrophages (Supplementary Figure 2). Polymyxin B treatment did not affect MAV2054 function, whereas the effects of LPS were significantly inhibited by polymyxin B.

Production of TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 from RAW264.7 cells or BMDMs stimulated with MAV2054 protein.

RAW264.7 cells (A) and BMDMs (B) were stimulated with MAV2054 (1, 5, 10 μg/mL), Ag85 (10 μg/mL), and LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1 levels in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. The results are the mean ± SD from three experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 for antigen treatments compared to untreated medium control (MC).

ROS are required for apoptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokine production induced by MAV2054

It is well-known that ROS can induce apoptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages33,34. To examine the involvement of ROS generation on the effects of MAV2054 in RAW264.7 cells, the oxidation of 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) was assessed by flow cytometry. MAV2054 induced a significant increase in intracellular ROS in macrophages compared to Ag85 or medium control (Fig. 3A). ROS production in MAV2054-treated RAW264.7 cells was increased in a dose-dependent manner (Supplementary Figure 3). MAV2054-mediated ROS production was dramatically reduced by pre-treatment with the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC). Next, we examined the apoptotic response in the presence of NAC to investigate the interplay between apoptosis and ROS generation. Pre-treatment with NAC significantly inhibited Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-positive cells induced by MAV2054 in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that increased ROS is essential for the apoptotic response caused by MAV2054. In addition, MAV2054-induced TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 levels were also significantly decreased in RAW264.7 cells or BMDMs by pre-treatment with NAC in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C and D), indicating that ROS, which are induced by MAV2054, are associated with the production of these cytokines and chemokines.

MAV2054-induced apoptosis and cytokine production are mediated by ROS production.

(A,B) RAW264.7 cells were treated with MAV2054 (10 μg/mL), Ag85 (10 μg/mL), LPS (100 ng/mL), or H2O2 (500 μM) in the presence or absence of NAC (10 mM) for 24 h. ROS levels (A) were measured by flow cytometry after DCFDA (10 μm) treatment. Data are representative flow cytometric analysis from three independent experiments. Apoptosis of RAW264.7 cells (B) was measured by flow cytometry using Annexin V/PI staining. Flow cytometric data shown are representative of at least three experiments. (C) RAW264.7 cells or (D) BMDMs pre-treated with or without antioxidant NAC (10, 20, 30 mM) for 1 h were stimulated with MAV2054 (10 μg/mL) for 24 h. The levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 from the culture supernatants were measured using by ELISA. All values are mean ± SD of three experiments. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 for NAC treatments compared to MAV2054 treatment alone. MC, medium control.

JNK activation is required for apoptosis induced by MAV2054

MAPKs are signalling factors known to play a critical role in inducing inflammatory cytokine production35 and have been linked to M. avium-induced macrophage apoptosis13. Thus, we examined whether MAPKs was activated in response to macrophage stimulation with MAV2054. The phosphorylation profiles of extracellular receptor kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), p38, JNK, and IκBα in RAW264.7 cells were analysed at various time-points after stimulation with MAV2054. ERK1/2, p38, and JNK were strongly phosphorylated at 15–30 min after stimulation (Fig. 4A). In addition, the expression of IκBα was rapidly lost at 5–15 min and then reappeared. These results suggest that MAV2054-induced macrophage activation is mediated by signalling pathways involving MAPKs and nuclear factor (NF)-κB. To confirm the role of MAPKs and NF-κB in MAV2054-induced cytokine production, BMDMs were pre-treated with a specific inhibitor of ERK1/2 (U0126), p38 (SB203580), JNK (SP600125), or NF-κB (BAY 11–7082) for 1 h, and cytokine levels were assayed at 24 h after MAV2054 stimulation. TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 were significantly suppressed by all inhibitors in a dose-dependent manner, except for MCP-1 which was significantly increased by the p38 inhibitor (Fig. 4B).

MAV2054-induced JNK activation is associated with ROS production and apoptosis.

(A) RAW264.7 cells stimulated with MAV2054 for the indicated times were lysed and the proteins in the total cell lysate were separated by SDS–PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with antibodies against phospho-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, phospho-p38, p38, phospho-JNK, JNK, IκBα, and β-actin. This image is representative of three experiments showing similar results. (B) BMDMs pre-incubated with inhibitors of ERK (U0126), p38 (SB203580), JNK (SP600125), and NF-ĸB (BAY11-7082) for 1 h were treated with MAV2054 (10 μg/mL) for 24 h. The levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 were measured by ELISA. ***P < 0.001 for inhibitor treatments compared to MAV2054 treatment alone. (C) RAW264.7 cells pre-incubated with or without NAC (10, 20, 30 mM) for 1 h were stimulated with MAV2054 (10 μg/mL) for 30 min. Activity of MAPKs was determined by immunoblot analysis. The data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results. (D) RAW264.7 cells were incubated with JNK inhibitor (SP600125, 10 μM) for 1 h prior to treatment with MAV2054 (10 μg/mL). After 24 h, apoptosis was analysed by flow cytometry. (E,F) JNK activity of MAV2054 (10 μg/mL)-stimulated RAW264.7 cells without (E) or with pre-treatment of NAC (F) up to 24 h was determined by immunoblot analysis. All values are the mean ± SD of three experiments. MC, medium control; UT, untreated.

Next, we assessed whether NAC could block the phosphorylation of MAPKs induced by MAV2054. As shown in Fig. 4C, NAC pre-treatment significantly inhibited JNK activation in a dose-dependent manner. However, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 was not suppressed in the presence of NAC. These data suggest that ROS are involved in MAV2054-mediated JNK activation. We further confirmed the involvement of JNK in MAV2054-mediated apoptosis. Flow cytometry showed that the JNK inhibitor significantly suppressed MAV2054-induced macrophage apoptosis (Fig. 4D). However, the p38 inhibitor could not suppress MAV2054-mediated Annexin V-FITC-positivity in cells (Supplementary Figure 4).

In addition, we examined the status of JNK phosphorylation after MAV2054 treatment. As shown in Fig. 4E, phosphorylation of JNK was significantly increased in a time-dependent manner and persisted for the duration of the experiment. To further analyse whether MAV2054-induced ROS generation was responsible for JNK activation, cells were pre-treated with NAC and then exposed to MAV2054 for up to 24 h. Pre-treatment with NAC suppressed the phosphorylation of JNK caused by MAV2054 (Fig. 4F). Overall, our results suggest that ROS/JNK signalling is involved in MAV2054-mediated apoptosis in macrophages.

MAV2054 decreases mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm) and increases cytochrome c release

The mitochondria play a central role in the response to apoptotic stimuli, allowing signals from various inputs to converge36. Damage to the mitochondrial membrane results in release the several death-promoting factors such as cytochrome c. We tested whether MAV2054 treatment affected the structural and biochemical integrity of the mitochondria. Mitochondrial damage was assessed by examining ΔΨm, which was determined by staining cells with 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine (DiOC6) for flow cytometric analysis. As shown in Fig. 5A, a significant dose-dependent decrease in ΔΨm was observed in RAW264.7 cells incubated with MAV2054, as indicated by the decrease in DiOC6 intensity compared to that in untreated or Ag85-treated cells. Next, we tested whether Bax, a pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, was translocated to the mitochondria, and cytochrome c was released into the cytoplasm from the mitochondria. An increase in cytochrome c in the cytosolic fraction was detected in cells treated with MAV2054 following subcellular fractionation and western blot analysis (Fig. 5B). However, MAV2054 did not cause Bax translocation into the mitochondria (Fig. 5C). These findings suggest that the apoptotic effect of MAV2054 on macrophages is associated with mitochondrial damage and cytochrome c release.

MAV2054 induces ΔΨm collapse and cytochrome c release.

RAW264.7 cells treated with Ag85 (10 μg/mL) or MAV2054 (1, 5, 10 μg/mL) for 24 h. (A) The cells were stained with DiOC6 (10 nM). The fluorescence activity of data are representative flow cytometric analysis from three independent experiments. (B,C) Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were prepared, and aliquots containing 20 μg of protein were subjected to western blot analysis and probed with antibodies against cytochrome c, Bcl-2 or Bax. α-Tubulin and VDAC or COX IV were used as markers for the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions, respectively. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

MAV2054 is targeted to the mitochondria

MAV2054-induced apoptosis occurred following the release of cytochrome c but was not related to Bcl-2 family signalling, indicating that cytochrome c release is due to factors other than MAV2054. It was previously demonstrated that a protein is targeted to the mitochondria and induces the release of cytochrome c to enhance the intrinsic response of apoptosis17. We also found that M. tuberculosis HBHA induces cytochrome c release through a direct interaction with the mitochondria9. Therefore, we evaluated where MAV2054 is localized in the mitochondria of cells treated with this protein. Confocal microscopy analysis revealed the presence of MAV2054 in the cytosol and mitochondria of MAV2054-treated cells, based on the significant overlap between MAV2054 and Mitotracker signals (Fig. 6A). Subcellular fractionation and western blot analysis consistently showed that large amounts of MAV2054 were detected in the cytosol and mitochondrial fractions, but the unrelated mycobacterial antigen Ag85 was not detected in the cytosol and mitochondrial fraction of BMDMs treated with Ag85 (Fig. 6B). Next, we further tested whether MAV2054 was transported to the mitochondria during M. avium infection. Confocal microscopy of infected cells revealed that some MAV2054 was colocalised with the mitochondria (Fig. 6C). The purified mitochondrial fraction and cytosolic fraction of these cells contained equal amounts of MAV2054 protein (Fig. 6D). In fact, the protein homologous to MAV2054 in M. leprae and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis is a membrane protein27,37. To determine the location of MAV2054 in M. avium, the bacteria were fractionated into cytosol, cell wall, and cell membrane components (Supplementary Figure 5a). Based on the results of western blotting, it appeared that MAV2054 was detected in both, the cell wall and the membrane fractions, but not in the cytosol fraction (Supplementary Figure 5b). Therefore, we further confirmed whether MAV2054 was released from phagosomes containing M. avium. The infected bacteria located in the phagosome and MAV2054 was detected in the phagosome, cytosol, and mitochondria (Supplementary Figure 6). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that MAV2054 is efficiently localised to the mitochondria of macrophages infected with M. avium.

Subcellular localization of MAV2054 in macrophages.

BMDMs were treated with MAV2054 (10 μg/mL) or Ag85 (10 μg/mL) for 24 h or infected with M. avium at MOI of 10 for 20 h. (A) Representative confocal images of medium control (MC) and MAV2054-treated cells. DNA visualized with DAPI (blue), MAV2054 (green), and F-actin (red) in the upper panel, and MAV2054 (green) and Mitotracker (Red) in lower panel. Yellow in merged images indicates co-localization. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were separated from cell lysates and examined by western blotting using specific antibodies against MAV2054, Ag85, VDAC, and α-tubulin. (C) Representative confocal images of MC and M. avium infected cells. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Localization of MAV2054 in BMDMs infected with M. avium at MOI of 10 for 4 h was analysed by western blotting using specific antibodies against MAV2054, VDAC, and α-tubulin. (E) RAW264.7 cells were treated with MAV2054 (10 μg/mL) or Ag85 (10 μg/mL), and H2O2 (500 μm) for 24 h. Cells were labelled with MitoSOX for 30 min and analysed for mitochondrial ROS levels by flow cytometry. A shift in the cell population to the right indicates the amount of ROS generation. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

Mitochondrial ROS generation causes ΔΨm disruption and apoptotic cell death38,39. We determined whether treatment of macrophages with MAV2054 induced mitochondrial ROS generation. The MitoSOX dye selectively binds to superoxide in the mitochondria. Flow cytometry analysis revealed a significant shift to a high intensity of this dye in RAW264.7 cells treated with MAV2054 compared to in untreated controls or Ag85 (Fig. 6E). These results demonstrated that ROS production in macrophages treated with MAV2054 was mainly increased through the mitochondria.

To determine whether the apoptotic activity of MAV2054 protein was dependent on the putative mitochondrial localization sequence (MLS), we wanted to identify the presence of MLS in the MAV2054 protein using the MitoProt II v1.101 (https://ihg.gsf.de/ihg/mitoprot.html). It was predicted that the MLS was located in the N-terminal of the MAV2054 protein. Three truncated forms of the recombinant protein with or without these target sequences were purified (Supplementary Figure 7b), and their activity was analyzed. FACS and DNA fragmentation assay revealed that the apoptotic response in macrophages treated with the truncated form lacking the putative mitochondrial target sequences was decreased (Supplementary Figure 7c and 7d). In addition, ROS production, caspase activation, and the decreased ΔΨm of MAV2054 correlated with the mitochondrial target sequences (Supplementary Figure 7e to 7g).

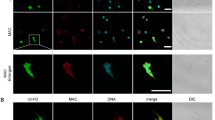

Mycobacterium smegmatis expressing MAV2054 increases apoptotic response of infected macrophages

To confirm the effects of MAV2054 during infection, M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 was generated and the protein expression in this bacteria was confirmed by western blotting (Supplementary Figure 8). First, we confirmed whether MAV2054 was also localized to the mitochondria in BMDMs infected with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054. Confocal microscopy and western blotting results revealed that some MAV2054 colocalised with the mitochondria (Fig. 7A and B). However, MAV2054 was not detected in cells infected with M. smegmatis expressing an empty plasmid (mock). Next, we analysed the effect of MAV2054 on macrophages in the context of the bacterium. A significant increase in the number of apoptotic cells and increased ROS production were observed in BMDMs infected with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 compared to in BMDMs infected with the M. smegmatis mock strain (Fig. 7C and D). Furthermore, more significant ΔΨm collapse was detected in cells infected with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 (Fig. 7E). These findings suggest that MAV2054 affects macrophage apoptosis during bacterial infection through mitochondrial targeting of this protein.

MAV2054 localization and increased apoptosis in macrophages infected with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054.

BMDMs were infected with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 or empty plasmid (mock) at an MOI of 5 for 20 h. (A) Representative confocal images of BMDM infected with mock strain and M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054. DNA visualized with DAPI (blue), MAV2054 (green), and Mitotracker (Red). Yellow in merged images indicates co-localization. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were separated from the cell lysates and examined by western blotting using specific antibodies against MAV2054, VDAC, and α-tubulin. (C) Apoptosis of the infected cells was analysed by flow cytometry using Annexin V/PI staining. (D) The infected cells were labelled with DCFDA (10 μm) for 30 min and analysed for ROS production. A shift in the cell population to the right indicates ROS generation. (E) The fluorescence activity of DiOC6 was determined by flow cytometry using DiOC6 (10 nM) staining. A shift in the cell population to the left indicates a loss of ΔΨm. Flow cytometric histograms are representative mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 for infected cells compared to uninfected cells. MC, medium control.

MAV2054 expression increases the survival rate of mice infected with M. smegmatis

It has been reported that more virulent strains of M. tuberculosis grow rapidly inside macrophages40, indicating that the intracellular survival rate of mycobacteria in macrophages can be used to indirectly assess their virulence. Therefore, to confirm the role of MAV2054-induced apoptosis, we measured the intracellular growth of M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 in macrophages. Intracellular growth of M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 at 24 h after infection was significantly decreased compared to the M. smegmatis mock strain (Fig. 8A). The reduced survival rate of M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 was recovered by pre-treatment with NAC (Fig. 8B). In contrast, there was no significant difference in LDH release between cells infected with M. smegmatis and M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 regardless of pre-treatment with NAC (Fig. 8C,D). Next, we confirmed the effect of MAV2054 expression in M. smegmatis in vivo. Mycobacterium smegmatis is generally considered a non-pathogenic organism. However, high-dose intravenous infection was fatal in C57BL/6 mice41. The survival rates of mice after intravenous M. smegmatis infection (1 × 107 CFU) were determined. All mice infected with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 survived for >10 days, whereas all mice inoculated with the M. smegmatis strain died by 5 days post-infection (Fig. 8E). FACS analysis of alveolar macrophages collected at 3 days post-infection revealed that M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 induced significant higher apoptosis of macrophages than in the mock strain. These results suggest that MAV2054-induced macrophage apoptosis is related to attenuation of M. smegmatis virulence.

MAV2054 expression suppresses M. smegmatis intracellular growth and increases survival rate of mouse infected with M. smegmatis.

BMDMs were infected with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 or M. smegmatis at an MOI of 5 for 24 h without (A,C) or with NAC (B,D). (A,B) At 0 h and 24, intracellular growth was determined by serial dilution of cell lysate and plating on 7H10 agar. **P < 0.01 for the comparison of infected cells with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 and M. smegmatis. (C,D) After 24 h, LDH release from the culture supernatants was measured using a Cytotoxicity Detection Kit. Positive controls were generated by treating cells with 1% Triton X-100 (TX-100) for 1 h prior to the assay. The results are the mean ± SD from three experiments. (E) Survival of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 per group) infected with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 or M. smegmatis strain intravenously at a high dose (1 × 107 CFU per mouse). Representative data from two experiments are shown. (F) Apoptotic population of alveolar macrophages from mouse (n = 3 per group) infected with the bacteria was analysed by flow cytometry using CD11b and F4/80, and Annexin V/PI staining at 3 days post-infection. The results are the mean ± SD of three mouse experiments. **P < 0.01 for infected mouse compared to non-infected mice.

Discussion

MAC live within macrophages, and infection of macrophages by MAC can lead to their apoptotic death; the induction of macrophage apoptosis is strain-specific13,14,15,42. Several components of M. tuberculosis that are involved in triggering apoptosis and their inducing mechanisms have been determined. However, the MAC components that evoke apoptotic response have not been identified. MAV2054 is a major membrane protein that plays a role in the invasion of bovine epithelial cells in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis37. In this study, we demonstrated that intracellular MAV2054 targets the mitochondria in macrophages, leading to ΔΨm dissipation, and eventual apoptosis. Our results show that MAC also contains a specific component that triggers host apoptotic responses via a mitochondria-dependent pathway during M. avium infection.

ROS molecules are involved in a variety of cellular signalling pathways, such as promoting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines43,44. Increased intracellular ROS levels can trigger apoptosis by activating the mitochondrial-dependent cell death pathway43. Our data suggest that increased ROS is essential for MAV2054-mediated macrophage apoptosis and MAV2054-induced TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 production. Other reports also showed that ROS are involved in M. avium- and its sonic extracts-induced macrophage apoptosis13,21. We also demonstrated that ROS production is required for macrophage apoptosis induced by M. avium MAV205222.

It is well-known that mycobacteria induce apoptosis via extrinsic and intrinsic pathways or a caspase independent pathway. M. avium-induced apoptosis is mediated by TNF and Fas14, indicating that an extrinsic pathway is involved. The Fas-associated death domain-mediated caspase 8 activation through ASK1/p38 MAPK signalling, as well as caspase 9 activation via the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway, appear to be involved in the signalling of apoptosis induced by M. avium13. As expected, we also observed the activation of caspase-3, caspase-9, and subsequent cleavage of PARP after incubation of macrophages with MAV2054. Activation of JNK, but not p38, was involved in MAV2054-mediated apoptosis. In fact, M. avium-mediated ASK1/p38 activation is triggers subsequent Fas-associated, death domain-mediated caspase 8 activation, which is involved in the extrinsic pathway13. Although JNK and p38 were strongly phosphorylated in MAV2054-induced macrophages, p38 may not be required for MAV2054-mediated apoptosis because MAV2054 induced apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway. Increasing evidence indicates a crucial role of JNK in mitochondria dysfunction and the subsequent initiation of apoptosis45. Particularly, it has been reported that various stimulants such as a natural derivative compound induce apoptosis with ROS-dependent JNK activation in target cells46,47,48. Our results additionally showed that NAC inhibited MAV2054-induced JNK activation, which was required for MAV2054-mediated apoptosis, suggesting that ROS/JNK signalling is involved in MAV2054-mediated apoptosis. In addition, MAV2054 induced activation of caspase 8, which results from ROS accumulation. ROS generation has been reported to activate ASK1, and increase the activity of caspase 849,50.

Mitochondria are central organelles in which a variety of key events in intrinsic apoptosis occur, including the release of cytochrome c, changes in electron transport, and pro- and anti-apoptotic molecule activity43. Mitochondrial damage and cytochrome c release are considered to be critical causes of macrophage apoptosis mediated by M. tuberculosis51,52 or M. avium14. Recently, we demonstrated that the M. tuberculosis HBHA protein is targeted to the mitochondria of macrophages, which leads to apoptosis through ROS production, mitochondrial translocation of Bax, ΔΨm collapse, and cytochrome c release9. Here, we found that the M. avium MAV2054 protein was targeted to the mitochondrial compartment of macrophages treated with MAV2054 and infected with M. avium. Dissipation of ΔΨm and depletion of cytochrome c also occurred in the mitochondria of MAV2054-treated macrophages. Furthermore, MAV2054 was transported to the mitochondria of BMDMs infected with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054. However, we found no evidence of mitochondrial translocation of Bax induced by MAV2054, indicating that molecules are not involved in MAV2054-induced cell death. ROS are predominantly produced in the mitochondria and lead to the modulation of ΔΨm, which finally results in apoptosis39. Our data indicate that ROS generated in macrophages treated with MAV2054 were mainly produced in the mitochondria. Therefore, mitochondrial localization of MAV2054 may lead to ROS generation, subsequently affecting ΔΨm loss and cytochrome c release; these processes play an essential role in MAV2054-induced apoptosis. Another possibility is that MAV2054 induces mitochondrial dysfunction via ROS-dependent JNK activation, because significant evidence has shown that JNK activation leads to mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis45. However, we could not identify which host molecules physically and functionally interacted with intracellular MAV2054 or the molecular mechanism related to mitochondrial dysfunction. Several mitochondria-targeted proteins expressed by pathogens interact with voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs)53,54. Recombinant MAV2054 used in this study was a His-tagged fusion protein. In fact, we tested whether MAV2054 interacts with VDAC or the Bcl-2 family of pro-apoptotic members by immunoprecipitation, using an anti-His antibody or anti-MAV2054 antibody. However, MAV2054 showed no direct interaction with VDAC or Bcl-2 family members.

The induction of host cell apoptosis in response to a bacterial pathogen can be considered from two perspectives: as a virulence mechanism of the pathogen or as a defence mechanism of the host55. Most research indicates that the apoptosis of macrophages infected with mycobacteria functions as a host defence mechanism to eliminate the bacteria. However, the induction of apoptosis as a virulence strategy to establish and spread mycobacterial infection has been reported56,57,58. In this study, BMDMs infected with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 showed a significantly increased apoptotic response and more significant ROS production and ΔΨm collapse compared to in the mock strain. Surprisingly, the intracellular growth of M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 within macrophages was significantly decreased. All mice infected with high doses of M. smegmatis died within 5 days, but mice with M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054 all survived. Collectively, our data suggest that the apoptosis of macrophages infected with M. avium represents a host defence mechanism against mycobacteria. To confirm this, however, precise molecular and cellular mechanisms by which MAV2054 decreases the intracellular survival rate of the bacteria via the mitochondrial apoptotic death pathway should be investigated.

In summary, the present study provides insights into the mechanisms by which MAV2054 induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway in macrophages. Importantly, it increases the understanding of the pathogenic mechanism of M. avium, as indicated by the fact that MAV2054 expression in the bacteria suppressed its intracellular growth in macrophages and increased the survival rate of infected mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Specific pathogen-free, 5–6 week-old, female C57BL/6 (H-2Kb and I-Ab) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA), and were maintained under barrier conditions in a biohazard animal room at the Medical Research Center of Chungnam National University (Daejeon, Korea). The animals were fed sterile, commercial mouse diet and were provided water ad libitum. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee at Chungnam National University (permission number: CNU-00517). All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Korean Food and Drug Administration.

Reagents and antibodies

Anti-PARP, anti-β-actin, anti-caspase-3, anti-caspase-9, VDAC, anti-phosphorylated ERK1/2, anti-phosphorylated p38, anti-phosphorylated JNK, anti-phosphorylated IκBα, anti-ERK1/2, anti-p38, anti-JNK, anti-Bcl-2, and anti-IκBα were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA). α-Tubulin, anti-Bax (6A7) and His-probe were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibodies against cytochrome c (for immunofluorescence, clone 6H2.B4; for western blot analysis, clone 7H8.2C12) were acquired from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA), and the anti-cytochrome oxidase subunit IV (COX IV) antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA), MitoSOX, DAPI, and DiOC6 were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA) and z-VAD-fmk, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG, and specific inhibitors of ERK (U0126), p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK; SB203580), JNK (SP600125), and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB; BAY 11-7082) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-F4/80 and anti-CD11b were performed as recommended by the manufacturer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA).

Recombinant MAV2054 protein, native Ag85 protein, and anti-MAV2054 antibody

Recombinant MAV2054 protein from Escherichia coli was produced and prepared as described previously26. Ag85 was purified from the culture filtrate protein of M. tuberculosis H37Rv as previously described by Lim et al.28. Prepared proteins were incubated overnight at 4 °C with polymyxin B-agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to remove endotoxin. The endotoxin content of the final prepared proteins was very low (<0.05 U/mL). To obtain antiserum against MAV2054, BALB/c mice were immunised intraperitoneally with 25 μg of purified recombinant MAV2054 emulsified in incomplete Freund’s adjuvants. The mice were injected with the antigen three times at intervals of 2 weeks, and the serum was collected 1 week after the final immunisation.

Cell culture

Murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), 1% HEPES, and 1% l-glutamine at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were isolated from femurs and tibias of C57BL/6 mice (6–8-week old) and then differentiated by growth for 3–5 days in medium containing M-CSF (25 μg/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

ELISA for cytokines

The culture supernatants were collected from RAW264.7 cell and BMDMs stimulated with various concentrations of MAV2054, LPS, or Ag85. Sandwich ELISAs for detecting the cytokines and chemokines in the culture supernatants were performed as recommended by the manufacturer (eBioscience). Plates were read on a Vmax kinetic microplate reader (Molecular Devices Co., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 450 mm.

MTT assay

RAW264.7 macrophages were seeded and stimulated with different concentrations of the recombinant protein in a final volume of 250 μL RPMI per well. The cell culture was incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cell cytotoxicity was tested by MTT assay by adding 10 μL of 5 mg/mL MTT. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 3–4 h, and then, 100 μL of DMSO was added, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm.

DNA fragmentation assay (apoptosis ELISA)

Cells were seeded in 96-well flat-bottom culture plates. After incubation with recombinant MAV2054 proteins, cells were collected, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and processed for quantification of cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments formed during apoptosis, using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay Cell Death Detection ELISA PLUS kit (Roche Diagnostic Corporation, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Annexin V/PI staining

To confirm the results of morphological analysis, Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining was performed. For Annexin V/PI assays, cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI and then monitored for apoptosis by flow cytometry in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Briefly, 0.5 × 106 cells were washed twice with PBS and stained with 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC and 10 μL of PI (5 μg/mL) in 1 × binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaOH, 2.5 mM CaCl2) for 15 min in the dark. Apoptotic cells were quantified using the FACS Canto II cytometer (BD Biosciences). Both early apoptotic (Annexin V-positive, PI-negative) and late apoptotic (double-positive for Annexin V and PI) cells were detected. Data were processed using Flow Jo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

Subcellular fractionation

Cells were harvested with PBS. The cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were purified using the Subcellular Protein Fraction Kit for Cultured Cells (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Immunoblotting

The cells were harvested at the indicated time points and then incubated in lysis buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor cocktail) for 30 min on ice. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay, and equal amounts of proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE, electroblotted onto polyvinylidine difluoride membranes, blocked, and incubated overnight with primary antibodies. The blots were probed with primary antibodies at optimised concentrations followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL; Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) was used, followed by exposure to chemiluminescence film to visualize proteins.

Subcellular fractionation of M. avium

Generally, the M. avium was grown to an OD600 ~0.8. Next, the cells were harvested, resuspended in 10 mL lysis buffer (PBS, 1 mM PMSF, protein cocktail inhibitor) and lysed by sonication. The lysates were centrifuged at 3,000 g for 30 min to separate whole cell lysates (WCL) from the supernatant. WCL was ultra-centrifuged at 27,000 g for 30 min to obtain the cell wall pellet (CW). The supernatant from the WCL fraction was further ultra-centrifuged at 100,000 g for two hours to separate the cell membrane fraction and obtain the pellet fraction(CM) and supernatant (cytoplasmic, Cyto). The CW and CM fraction were washed once with lysis buffer, re-centrifuged, and subsequently, re-suspended in 0.5 mL of lysis buffer. All centrifugation steps were performed at 4 °C.

Measurement of ROS

Intracellular ROS were evaluated by staining cells with H2DCFDA (to measure total cellular H2O2) and/or MitoSOX (to measure the mitochondrial ROS superoxide). Cells were harvested with PBS. For ROS staining, 10 μM H2DCFDA and/or MitoSOX were added to cells for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark, and then the cells were washed with PBS. Samples were immediately analysed on a FACS Canto II cytometer (BD Biosciences) and the data were processed using Flow Jo software.

Assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)

Mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed by measuring the retention of the lipophilic cationic dye DiOC6 in the mitochondria. Cells were harvested and incubated in DiOC6 solution (10 nM in fresh medium) for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark. The cells were then washed and resuspended in PBS. Immediately after PBS washing, ΔΨm was measured by sorting the cells using the FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were excluded by forward and side-scatter gating. Data were analysed using Flow Jo software.

Confocal microscopy

Cells were seeded onto glass coverslips in 12-well plates. The subcellular localization of MAV2054 was analysed using a confocal microscope (LSM510 META; Carl Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany). The cells were incubated with Mitotracker Red (Molecular Probes). After washing, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, permeabilised with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, blocked with PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin for 1 h, stained with primary anti-MAV2054 antibody for 1 h, and then stained with secondary antibody (anti-mouse IgG FITC; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) for 1 h. DAPI staining was conducted for 10 min. Cells were washed with PBS between each step. The cytosol localization of MAV2054 was analysed using a confocal microscope. The cells were fixed, permeabilised, and stained with an anti-MAV2054 antibody followed by an anti-mouse IgG FITC (DAKO). After DAPI staining with Texas Red®-X phalloidin (Molecular Probes) for 20 min, the cells were imaged under a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Transformation and isolation of recombinant M. smegmatis strains

Preparation of M. smegmatis competent cells and electroporation procedures were performed following standard procedures59. Briefly, M. smegmatis stain mc2155 was grown in 7H9/ADC/Tw (7H9 containing 10% ADC (Microbiol, Cagliari, Italy) and 0.05% Tween 80 (Sigma)) until mid-log phase. Cells were then harvested and washed twice with cold 10% glycerol and resuspended in the same buffer. Next, 0.2 mL of competent cells was electroporated using standard settings: 1.5 kV, 1000 Ω, and 25 μF, using the Cene Pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The cells were harvested with 1 mL of warm 7H9/ADC/Tw, incubated for 4 h at 37 °C with gentle shaking, and differential dilutions of the culture were plated into 7H11/OADC plates containing 50 μg/mL hygromycin (Sigma). Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 3–4 days to obtain the recombinant strains.

Intracellular survival assay

BMDMs were infected with M. smegmatis at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 for 2 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Amikacin (200 μg/mL; Sigma) was added to each well and incubated for 2 h. After incubation, the supernatant was collected and the cells were lysed with sterile distilled water for 20 min. Cell lysates and collected supernatants were serially diluted and plated onto 7H10 agar plates to determine the “input” bacterial numbers.

Mouse infection and lung cell preparation

The mice C57BL/6 were divided into two groups: M. smegmatis, and M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054, with each group containing five mice. Mice in the two groups were inoculated intravenously with 1 × 107 CFU of either M. smegmatis or M. smegmatis expressing MAV2054, diluted with 200 μL of PBS. Mouse lungs were cut into pieces and agitated in 5 mL of cellular dissociation buffer (RPMI medium containing 0.1% collagenase type IV (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ, USA), 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2) for 15 min at 37 °C. Then lungs were homogenized and aggregates were filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer. Alveolar macrophages were analysed by flow cytometry using CD11b+ and F4/80+, and Annexin V/PI staining.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed independently and repeated at least three times. A P-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant in Student’s t-tests. Data are presented as the mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lee, K.-I. et al. Mycobacterium avium MAV2054 protein induces macrophage apoptosis by targeting mitochondria and reduces intracellular bacterial growth. Sci. Rep. 6, 37804; doi: 10.1038/srep37804 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Field, S. K., Fisher, D. & Cowie, R. L. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease in patients without HIV infection. Chest 126, 566–581 (2004).

Simons, S. et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in respiratory tract infections, eastern Asia. Emerging infectious diseases 17, 343–349 (2011).

Triccas, J. A. et al. Molecular and immunological analyses of the Mycobacterium avium homolog of the immunodominant Mycobacterium leprae 35-kilodalton protein. Infection and immunity 66, 2684–2690 (1998).

Lagrange, P. H., Wargnier, A. & Herrmann, J. L. Mycobacteriosis in the compromised host. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 95 Suppl 1, 163–170 (2000).

Vankayalapati, R. et al. Cytokine profiles in immunocompetent persons infected with Mycobacterium avium complex. The Journal of infectious diseases 183, 478–484 (2001).

Arend, S. M., van Soolingen, D. & Ottenhoff, T. H. Diagnosis and treatment of lung infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine 15, 201–208 (2009).

Sakamoto, K. The pathology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Veterinary pathology 49, 423–439 (2012).

Carvalho, R. V., Kleijn, J., Meijer, A. H. & Verbeek, F. J. Modeling innate immune response to early Mycobacterium infection. Computational and mathematical methods in medicine 2012, 790482 (2012).

Sohn, H. et al. Targeting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis heparin-binding hemagglutinin to mitochondria in macrophages. PLoS pathogens 7, e1002435 (2011).

Smith, I. Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis and molecular determinants of virulence. Clinical microbiology reviews 16, 463–496 (2003).

Fernandez-Prada, C. M. et al. Interactions between Brucella melitensis and human phagocytes: bacterial surface O-Polysaccharide inhibits phagocytosis, bacterial killing, and subsequent host cell apoptosis. Infection and immunity 71, 2110–2119 (2003).

Lopez, M. et al. The 19-kDa Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein induces macrophage apoptosis through Toll-like receptor-2. Journal of immunology 170, 2409–2416 (2003).

Bhattacharyya, A. et al. Execution of macrophage apoptosis by Mycobacterium avium through apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and caspase 8 activation. The Journal of biological chemistry 278, 26517–26525 (2003).

Bermudez, L. E., Parker, A. & Petrofsky, M. Apoptosis of Mycobacterium avium-infected macrophages is mediated by both tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and Fas, and involves the activation of caspases. Clinical and experimental immunology 116, 94–99 (1999).

Fratazzi, C., Arbeit, R. D., Carini, C. & Remold, H. G. Programmed cell death of Mycobacterium avium serovar 4-infected human macrophages prevents the mycobacteria from spreading and induces mycobacterial growth inhibition by freshly added, uninfected macrophages. Journal of immunology 158, 4320–4327 (1997).

Early, J., Fischer, K. & Bermudez, L. E. Mycobacterium avium uses apoptotic macrophages as tools for spreading. Microbial pathogenesis 50, 132–139 (2011).

Sanchez, A., Espinosa, P., Garcia, T. & Mancilla, R. The 19 kDa Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoprotein (LpqH) induces macrophage apoptosis through extrinsic and intrinsic pathways: a role for the mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Clinical & developmental immunology 2012, 950503 (2012).

Dao, D. N. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipomannan induces apoptosis and interleukin-12 production in macrophages. Infection and immunity 72, 2067–2074 (2004).

Basu, S. et al. Execution of macrophage apoptosis by PE_PGRS33 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by Toll-like receptor 2-dependent release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. The Journal of biological chemistry 282, 1039–1050 (2007).

Sanchez, A. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis 38-kDa lipoprotein is apoptogenic for human monocyte-derived macrophages. Scandinavian journal of immunology 69, 20–28 (2009).

Hayashi, T., Catanzaro, A. & Rao, S. P. Apoptosis of human monocytes and macrophages by Mycobacterium avium sonicate. Infection and immunity 65, 5262–5271 (1997).

Lee, K. I. et al. Mycobacterium avium MAV2052 protein induces apoptosis in murine macrophage cells through Toll-like receptor 4. Apoptosis: an international journal on programmed cell death 21, 459–472 (2016).

Byun, E. H. et al. Rv0315, a novel immunostimulatory antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, activates dendritic cells and drives Th1 immune responses. Journal of molecular medicine 90, 285–298 (2012).

Kim, K. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv0652 stimulates production of tumour necrosis factor and monocytes chemoattractant protein-1 in macrophages through the Toll-like receptor 4 pathway. Immunology 136, 231–240 (2012).

Byun, E. H. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv0577, a novel TLR2 agonist, induces maturation of dendritic cells and drives Th1 immune response. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 26, 2695–2711 (2012).

Shin, A. R. et al. Serodiagnostic potential of Mycobacterium avium MAV2054 and MAV5183 proteins. Clinical and vaccine immunology: CVI 20, 295–301 (2013).

Marques, M. A., Chitale, S., Brennan, P. J. & Pessolani, M. C. Mapping and identification of the major cell wall-associated components of Mycobacterium leprae. Infection and immunity 66, 2625–2631 (1998).

Lim, J. H. et al. Purification and immunoreactivity of three components from the 30/32-kilodalton antigen 85 complex in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infection and immunity 67, 6187–6190 (1999).

Giri, P. K., Verma, I. & Khuller, G. K. Enhanced immunoprotective potential of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ag85 complex protein based vaccine against airway Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge following intranasal administration. FEMS immunology and medical microbiology 47, 233–241 (2006).

Chang, S. C. & Ding, J. L. Ubiquitination by SAG regulates macrophage survival/death and immune response during infection. Cell death and differentiation (2014).

Chen, F. et al. Proinflammatory caspase-2-mediated macrophage cell death induced by a rough attenuated Brucella suis strain. Infection and immunity 79, 2460–2469 (2011).

Bidzhekov, K., Zernecke, A. & Weber, C. MCP-1 induces a novel transcription factor with proapoptotic activity. Circulation research 98, 1107–1109 (2006).

Choi, J. A. et al. Mycobacterial HBHA induces endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis through the generation of reactive oxygen species and cytosolic Ca2+ in murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cells. Cell death & disease 4, e957 (2013).

Lim, Y. J. et al. Mycobacterium kansasii-induced death of murine macrophages involves endoplasmic reticulum stress responses mediated by reactive oxygen species generation or calpain activation. Apoptosis: an international journal on programmed cell death 18, 150–159 (2013).

Seo, S. K. et al. Sulindac-derived reactive oxygen species induce apoptosis of human multiple myeloma cells via p38 mitogen activated protein kinase-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Apoptosis: an international journal on programmed cell death 12, 195–209 (2007).

Kroemer, G. Mitochondrial control of apoptosis: an overview. Biochemical Society symposium 66, 1–15 (1999).

Bannantine, J. P., Huntley, J. F., Miltner, E., Stabel, J. R. & Bermudez, L. E. The Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis 35 kDa protein plays a role in invasion of bovine epithelial cells. Microbiology 149, 2061–2069 (2003).

Wang, C. C., Fang, K. M., Yang, C. S. & Tzeng, S. F. Reactive oxygen species-induced cell death of rat primary astrocytes through mitochondria-mediated mechanism. Journal of cellular biochemistry 107, 933–943 (2009).

Gupta, S. et al. Arsenic trioxide induces apoptosis in peripheral blood T lymphocyte subsets by inducing oxidative stress: a role of Bcl-2. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2, 711–719 (2003).

Park, J. S., Tamayo, M. H., Gonzalez-Juarrero, M., Orme, I. M. & Ordway, D. J. Virulent clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis grow rapidly and induce cellular necrosis but minimal apoptosis in murine macrophages. Journal of leukocyte biology 79, 80–86 (2006).

Sweeney, K. A. et al. A recombinant Mycobacterium smegmatis induces potent bactericidal immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature medicine 17, 1261–1268 (2011).

Gan, H., Newman, G. W. & Remold, H. G. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2 prevents programmed cell death of human macrophages infected with Mycobacterium avium, serovar 4. Journal of immunology 155, 1304–1315 (1995).

Green, D. R. & Reed, J. C. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 281, 1309–1312 (1998).

Bulua, A. C. et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species promote production of proinflammatory cytokines and are elevated in TNFR1-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). The Journal of experimental medicine 208, 519–533 (2011).

Tournier, C. et al. Requirement of JNK for stress-induced activation of the cytochrome c-mediated death pathway. Science 288, 870–874 (2000).

Zeng, F. et al. Induction of apoptosis by casticin in cervical cancer cells: reactive oxygen species-dependent sustained activation of Jun N-terminal kinase. Acta biochimica et biophysica Sinica 44, 442–449 (2012).

Mao, X., Yu, C. R., Li, W. H. & Li, W. X. Induction of apoptosis by shikonin through a ROS/JNK-mediated process in Bcr/Abl-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cells. Cell research 18, 879–888 (2008).

Shi, Y. et al. ROS-dependent activation of JNK converts p53 into an efficient inhibitor of oncogenes leading to robust apoptosis. Cell death and differentiation 21, 612–623 (2014).

Kang, N. et al. Inhibition of caspase-9 by oridonin, a diterpenoid isolated from Rabdosia rubescens, augments apoptosis in human laryngeal cancer cells. International journal of oncology 47, 2045–2056 (2015).

Chen, L. et al. The marine fungal metabolite, dicitrinone B, induces A375 cell apoptosis through the ROS-related caspase pathway. Marine drugs 12, 1939–1958 (2014).

Duan, L., Gan, H., Golan, D. E. & Remold, H. G. Critical role of mitochondrial damage in determining outcome of macrophage infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of immunology 169, 5181–5187 (2002).

Chen, M., Gan, H. & Remold, H. G. A mechanism of virulence: virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv, but not attenuated H37Ra, causes significant mitochondrial inner membrane disruption in macrophages leading to necrosis. Journal of immunology 176, 3707–3716 (2006).

Rahmani, Z., Huh, K. W., Lasher, R. & Siddiqui, A. Hepatitis B virus X protein colocalizes to mitochondria with a human voltage-dependent anion channel, HVDAC3, and alters its transmembrane potential. Journal of virology 74, 2840–2846 (2000).

Massari, P., Ho, Y. & Wetzler, L. M. Neisseria meningitidis porin PorB interacts with mitochondria and protects cells from apoptosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97, 9070–9075 (2000).

Barry, D. P. & Beaman, B. L. Modulation of eukaryotic cell apoptosis by members of the bacterial order Actinomycetales. Apoptosis: an international journal on programmed cell death 11, 1695–1707 (2006).

Aporta, A. et al. Attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis SO2 vaccine candidate is unable to induce cell death. PloS one 7, e45213 (2012).

Gao, L. Y. et al. A mycobacterial virulence gene cluster extending RD1 is required for cytolysis, bacterial spreading and ESAT-6 secretion. Molecular microbiology 53, 1677–1693 (2004).

Davis, J. M. & Ramakrishnan, L. The role of the granuloma in expansion and dissemination of early tuberculous infection. Cell 136, 37–49 (2009).

Bardarov, S. et al. Conditionally replicating mycobacteriophages: a system for transposon delivery to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94, 10961–10966 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and future Planning (2013R1A2A1A03069903).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.I.L. and H.J.K. designed the research. K.I.L., J.W., H.G.C., Y.J.S., H.S.J., Y.W.B., H.S.P. and S.P. performed the experiments. K.I.L., C.H.C., J.K.P. and H.J.K. analysed the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, KI., Whang, J., Choi, HG. et al. Mycobacterium avium MAV2054 protein induces macrophage apoptosis by targeting mitochondria and reduces intracellular bacterial growth. Sci Rep 6, 37804 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37804

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37804

This article is cited by

-

Effect and Mechanism of Mycobacterium avium MAV-5183 on Apoptosis of Mouse Ana-1 Macrophages

Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics (2024)

-

Meeting the challenges of NTM-PD from the perspective of the organism and the disease process: innovations in drug development and delivery

Respiratory Research (2022)

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3463 induces mycobactericidal activity in macrophages by enhancing phagolysosomal fusion and exhibits therapeutic potential

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Phagocytosis influences the intracellular survival of Mycobacterium smegmatis via the endoplasmic reticulum stress response

Cell & Bioscience (2018)

-

Mycobacterium fortuitum-induced ER-Mitochondrial calcium dynamics promotes calpain/caspase-12/caspase-9 mediated apoptosis in fish macrophages

Cell Death Discovery (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.