Abstract

NR5A1 is essential for the development and for the function of steroid producing glands of the reproductive system. Moreover, its misregulation is associated with endometriosis, which is the first cause of infertility in women. Hr39, the Drosophila ortholog of NR5A1, is expressed and required in the secretory cells of the spermatheca, the female exocrine gland that ensures fertility by secreting substances that attract and capacitate the spermatozoids. We here identify a direct regulator of Hr39 in the spermatheca: the Gcm transcription factor. Furthermore, lack of Gcm prevents the production of the secretory cells and leads to female sterility in Drosophila. Hr39 regulation by Gcm seems conserved in mammals and involves the modification of the DNA methylation profile of mNr5a1. This study identifies a new molecular pathway in female reproductive system development and suggests a role for hGCM in the progression of reproductive tract diseases in humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In mammals and insects, the process of spermatozoid maturation occurs first in the male before copulation and second after copulation where molecules secreted by the female reproductive tract epithelium preserve and capacitate the spermatozoids1,2,3,4. Capacitation is primordial for fertilisation and spermatozoids are viable in the female reproductive tract for several days in human5, several years in honey bees6,7 and several decades in ants8. In both mammals and insects, the inability to capacitate/store the spermatozoids has a strong impact on female fertility9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

Several insect species have developed specific structures called spermathecae that preserve the spermatozoids well after copulation in the female reproductive tract. The molecules that attract, store and capacitate the spermatozoids in the spermatheca are produced by a layer of secretory cells (SC)12. The hormone receptor Hr39 allows the generation of the SC, hence ensuring female fertility. Two mammalian orthologs of Hr39 have been described. The nuclear receptor 5A2 (NR5A2 also known as LRH-1) was associated with pre-eclampsia in humans and is involved in cell proliferation, bile acid metabolism and steroidogenesis16,17. The nuclear receptor 5A1 (NR5A1 also known as SF-1) (human NR5A1 gene is hNR5A1 and mouse ortholog is mNr5a1 throughout the text)14,15 is involved in the development and in the function of the pituitary gland, of the adrenal gland and of the gonads18,19. Its mutation leads to severe defects in sexual organ formation and its misexpression is associated with changes in its DNA methylation profile and with endometriosis, the major cause of infertility in women20,21,22,23.

In this study, we identify the zinc finger transcription factor Glial cells missing (Gcm also known as Glial cell deficient or Glide) as a major transcriptional regulator of Hr39 during Drosophila spermatheca development. While the complete lack of Gcm leads to embryonic lethality due to the loss of glia24, we show that its partial lack is compatible with life and leads to almost complete sterility in females. In addition, clones of cells completely lacking Gcm in the spermatheca are devoid of SC. We show that Gcm controls the differentiation of the SC by controlling the expression of Hr39 directly. Such transcriptional control seems evolutionarily conserved, as the Gcm murine orthologs (mGCM1 and mGCM2), which were described for their expression in placenta, parathyroid, thymus, kidney and nervous system25,26,27,28,29, are also expressed in the uterus. Finally, assays in cells indicate that the Gcm family promotes the expression of mNR5A1/hNR5A1 and that the mGCM proteins induce the same changes in the DNA methylation of the hNR5a1 locus as those observed in endometriosis.

Collectively, our data reveal the regulatory pathway underlying SC differentiation in the Drosophila spermatheca and the conserved regulation of Hr39 and NR5A1, which represents the first evidence of the functional conservation of the Gcm transcription factors. Understanding the regulation of Hr39 expression may shed light on the physiopathological mechanisms of the major cause of infertility in women.

Results

Gcm is required for female fertility and is expressed in the Drosophila spermatheca

In Drosophila, the complete lack of the Gcm protein leads to embryonic lethality due to the transformation of glial cells into neurons24,30,31. Viable hypomorphic mutations, however, allow the analysis of gcm mutant animals at later stage24,31,32,33: the gcmrA87 allele is due to the insertion of a P-element containing the LacZ gene in the promoter of gcm and the gcmGal4 allele has been produced upon replacement of the LacZ by the Gal4 gene24,31,32,33. The gcmGal4 homozygous and the transheterozygous gcmGal4/gcmrA87 animals reach adulthood and display fertility defects. To assess whether the defects are sex specific, we crossed wild type (WT, Oregon-R) males with gcmGal4 homozygous or with transheterozygous females and found a significantly reduced number of offspring compared to that obtained in control crosses (<1% and 20% of the progeny, respectively, Fig. 1a). In contrast, fertility assays on transheterozygous males showed no fertility defects (data not shown). Thus, Gcm is required in reproduction in females, in addition to its well-known role in glia and blood development24,30,31,34,35,36,37,38.

Gcm is expressed in the spermatheca and controls fertility.

(a) Fertility assays carried out on gcm hypomorphs. The histogram shows the average number of progenies per female of the following genotypes: wild type (WT), gcmGal4/+ and gcmrA87/+, which represent the control strains, as well as gcmGal4/gcmrA87 and gcmGal4/gcmGal4, which represent gcm hypomorphic conditions. Ten crosses were made per genotype (n = 10). The error bars represent standard errors of the mean (s.e.m.). Student test was used to calculate the p-values: >0.05 = ns; <0.05–0.01 <= *; <0.01–0.001 <= **; <0.001 = ***. (b) Reproductive system of an adult control female (gcmGal4/+;UAS-RFP). Overlay of the images taken with white light and by epifluorescence (561nm). The scale bar represents 500 μm. (c) GO-term enrichment analysis of the genes directly targeted by Gcm according to a DamID screen39. The histogram represents the fold enrichments obtained for GO-terms linked to reproduction (enrichment >1.5, FDR <2%, p-value < 10−3), n = number of genes. (d) Overlap between the direct targets of Gcm according to a DamID screen (blue) and the genes expressed in spermatheca according to a spermatheca transcriptome13.

To clarify the role of Gcm on fertility, we crossed the gcmGal4 driver, which faithfully mimics the expression of Gcm32,33, with a UAS-RFP reporter. RFP expression was detected in the adult spermatheca, while no labelling was observed in the ovaries nor in the oviduct (Fig. 1b). Gcm expression in the adult spermatheca was confirmed by qPCR assays (Supplemental Figure S1).

Finally, a GO-term analysis on a genome-wide screen aiming at identifying the direct targets of Gcm39 specifically highlighted the genes involved in the reproductive system development as the most enriched class of genes after those involved in nervous system development, in line with the known role of Gcm at the glial determinant24,30,31 (Fig. 1c). Comparison between this screen and the published transcriptome of the spermatheca13 revealed that 387 direct targets of Gcm are expressed in this organ (Fig. 1d, list in Supplemental Table S1).

This data indicate that Gcm is necessary for female fertility and that it is expressed in the spermatheca.

The gcm mutation affects the secretory cells of the spermathecae

Two elegant studies14,40 showed that the spermatheca of Drosophila contains a layer of lumen epithelial cells (LEC) expressing the Runt-domain transcription factor Lozenge (Lz), which is essential for the development of the whole spermatheca14 (Fig. 2a). Surrounding the LEC is the layer of SC that express and require the transcription factor Hindsight (Hnt)15. Accessory cells are located basal (basal cells, BC) to the SC and apical (apical cells, AC) to the LEC. The AC are thought to secrete a cuticular canal that connects the secretory unit to the lumen of the spermatheca, which contains the spermatozoids. AC and BC undergo apoptosis during pupal spermatheca development, with some BC being still present in young adult females14.

Gcm is involved in the development of the secretory cells of the spermatheca.

(a) Schematic representation of an adult spermatheca cross-section. The SC express Hindsight (Hnt) and the LEC Lozenge (Lz). (b–d) Spermathecae analysed by bright-field microscopy. The spermathecae were dissected from adult females (1 to 3-day-old) gcmGal4/+ (control) (b), gcmGal4 (c), and gcmGal4/+;UAS-gcm/+ (gcm > gcm GOF) (d). Unless otherwise specified, all scale bars here and in the following figures represent 20 μm. (e–g) Single optical sections of spermathecae analysed by confocal microscopy from adult females of the following genotypes: gcmGal4/+ (e,e’), gcmGal4 (f) and gcmGal4/+;UAS-gcmRNAi/+ (gcm > gcm KD) (g) labelled with anti-Hnt (Hnt, in red) and DAPI (blue). (e) and (e’) represent the DAPI and the overlap of DAPI and anti-Hnt labelling of the gcmGal4/+ spermatheca, respectively. (h) Average number of secretory cells counted in cross-sections of adult spermathecae of the indicated genotypes (see materials and methods). At least 6 spermathecae were analysed per genotype, the error bars and p-values are as described for Fig. 1a. (i) Number of eggs laid per female and per day for the indicated genotypes. At least five replicates were made per genotype. (j–k”’) MARCM clonal analysis in a gcm mutant background. The images represent full projections of spermathecae analysed by confocal microscopy from adult females showing WT (j–j”’) or gcm34 mutant (k–k”’) clones. The spermathecae were labelled with anti-GFP (the clones express GFP, in green), anti-Hnt (Hnt, in red) and DAPI (blue) (j,k), the clones are indicated by dashed lines. Each marker is shown individually in (j’ and k’) for anti-GFP, (j” and k”) for anti-Hnt and (j”’ and k”’) for DAPI. The insets in (j”’ and k”’) show a higher magnification of the nuclei with the DAPI in grey. See also Supplemental Figures S2 and S4.

To assess the mode of action of Gcm, we analysed the morphology of the spermathecae in animals carrying altered levels of Gcm. The WT SC appear as a translucent layer of cells surrounding a dark cuticular structure that is produced by the LEC (Fig. 2b). In hypomorphic gcm conditions (gcmGal4 homozygous animals), the SC layer is completely absent, leaving the dark cuticular structure relatively unaffected (Fig. 2c). Accordingly, immunolabelling assays show a complete lack of SC in homozygous gcmGal4 females (Fig. 2f,h), which leads to the absence of spermatozoids in the spermathecae (Supplemental Figures S2a–d). The lack of SC in gcm homozygous females is also observed in other hypomorphic gcm conditions such as transheterozygous gcmGal4/gcmrA87 animals and can be rescued by overexpressing Gcm (Supplemental Figures S2e–g). Of note, some spermathecae from transheterozygous gcmGal4/gcmrA87 animals show few remaining SC (Supplemental Figure S2h’), explaining why this strain is not completely sterile. In addition, the number of SC significantly decreases when Gcm is knocked-down by RNAi (gcm KD) using the gcmGal4 as a driver (Fig. 2g,h). The egg laying rate is in agreement with this data. A positive correlation was previously made between the number of SC of the spermathecae and the number of eggs laid15 and indeed the number of SC as well as the egg laying rate decrease in gcm hypomorphs (Fig. 2h,i). The reduction in SC number no longer persists in gcm KD spermathecae that also carry the UAS-gcm transgene. Indeed, these spermathecae carry supernumerary SC (Fig. 2h), suggesting that Gcm expression may be sufficient to induce the differentiation of the SC.

Finally, to analyse the phenotype of a null gcm allele, MARCM clones were produced using the Df(2L)132 strain in which the gcm gene is completely deleted33,41 (Supplemental Figure S2i). Similar clonal analyses were also performed using a gcm hypomorphic but lethal mutation induced by P-element mutagenesis, gcm34 24 (Fig. 2j–k”’). Recombination was induced at the 3rd instar larval stage prior to spermatheca differentiation. WT clones contain both cell types (SC and LEC), whereas Df(2L)132 and gcm34 mutant clones contain LEC but completely lack SC. Thus, Gcm is necessary for the differentiation of SC. Given the strong phenotype observed in loss of function gcm alleles, we assessed the consequences of overexpressing Gcm in its own territory of expression in WT animals (gcm > gcm GOF). In these gain of function (GOF) animals, the dark cuticular structure and the LEC are present but the morphology of the spermatheca is altered (Fig. 2d, Supplemental Figures S2j-j”). In addition, these spermathecae display a very high number of SC (Fig. 2h).

Altogether, this data clearly indicate that Gcm is expressed and required in the spermatheca to control SC differentiation.

Gcm is expressed in the precursors of the secretory cells

The mutant phenotype prompted us to assess the role and the mode of action of Gcm. Given the early and transient expression of Gcm in glial cells24,30,31, we analysed the mutant spermathecae and the profile of Gcm expression during development. Spermathecae develop during the pupal stage and the different cell types arise from multipotent precursors (MP) that express Lz and divide to produce the lumen epithelium precursors (LEP) also expressing Lz as well as the secondary precursors called Secretory Unit Precursors (SUP), which do not express Lz14. Each SUP divides and produces the AC and a tertiary precursor, which in turn divides and produces the SC as well as the BC that undergoes apoptosis at the adult stage (Fig. 3h)14.

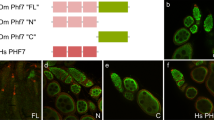

Gcm is expressed early in the secretory cell precursor to initiate the differentiation of the secretory cell.

(a–c) Single confocal sections of spermathecae from adult females (1 to 3-day-old) lzGal4,UAS-mCD8GFP/+ (control) (a), lzGal4,UAS-mCD8GFP/+;UAS-gcmRNAi (lz > gcm KD) (b) and lzGal4,UAS-mCD8GFP/+;UAS-gcm (lz > gcm GOF) (c) labelled with anti-GFP (lz > GFP, in green), anti-Hnt (Hnt, in red) and DAPI (blue). The region indicated by the white square in (b) is magnified in (b’) and (b”), in which the LEC are indicated by a dashed line. DAPI is in grey in (b”). (c’) Bright-field image of a lz > gcm GOF spermatheca. (d–d”’) Confocal projection of a gcmGal4/+;g-trace/+ (gcm > g-trace) adult spermatheca labelled with anti-Hnt (Hnt, in red), anti-GFP (gcm > g-trace, in green) and DAPI (blue). (d) represents the overlay of anti-Hnt, anti-GFP and DAPI, (d’) shows the DAPI labelling, (d”) Gcm lineage and Hnt and (d”’) anti-Hnt. The white asterisks indicate the SC and the LEC are indicated by a dashed line. (e–g”’) Confocal projections of lzGal4,UAS-mCD8GFP/+;gcmrA87/+ pupal spermathecae labelled with anti-βgal (gcm-lacZ, in grey), anti-Hnt (Hnt, in red), anti-GFP (lz > GFP, in green) and DAPI (blue). The images were taken at 28 hrs after puparium formation (APF) (e–e”’), 48 hrs APF (f–f”’) and 72 hrs APF (g–g”’). Each marker is shown individually in (e–g) for anti-GFP, (e’,f’,g’) for anti-Hnt, (e”,f”,g”) for anti-βgal and the overlay of the three channels and DAPI is shown in (e”’,f”’,g”’). The white arrowheads indicate cells expressing Gcm and Hnt, which correspond to the SUP, the empty arrowheads indicate cells expressing Lz and Gcm, which correspond to the MP (e–e”’). The inset (in f”’) shows SC expressing Hnt and low levels of Gcm, BC expressing high levels of Gcm, an AC expressing Hnt only and an LEC expressing Lz. (h) Schematic representation of spermatheca development (modified from ref. 15). The time scale is indicated above the schematic in hours APF. The yellow circles indicate Lz expression, the red circles Hnt and the green circles Gcm expression. The skull pictograms indicate the cells undergoing apoptosis. See also Figure S3.

First, we knocked down Gcm expression using the lzGal4 driver (lz > gcm KD), which is active in the MP. Like in hypomorphic conditions and in gcm > gcm KD animals, RNAi-mediated down-regulation of Gcm in the MP leads to the decrease of the number of SC in the adult spermatheca (Fig. 3a,b) and the LEC are not impacted (Fig. 3b–b”). The similar phenotypes obtained with gcm> and lz>, a driver that is not active in the SUP14, suggest that the gcm promoter is already active in the MP that generates all cell types of the spermatheca (including SC and LEC). We then proceeded to overexpress Gcm under the control of the lzGal4 driver (lz > gcm GOF) and found that this leads to severe spermatheca defects including a deformed and almost absent cuticular structure. This phenotype is stronger than the overexpression of Gcm using the gcmGal4 driver (gcm > gcm GOF) in which the cuticular structure can still be observed (compare Fig. 3c’ and Supplemental Figures S2j–j”). This indicates that premature Gcm expression prevents LEC development and suggests that Gcm is expressed below threshold levels in the MP.

Following this, we tracked the lineage of the Gcm expressing cells by crossing the g-trace flies42 with the gcmGal4 flies and found that both SC and LEC originate from cells expressing Gcm (white asterisks and dashed line, respectively, in Fig. 3d–d”’). In addition, we tracked Gcm expression during spermatheca development using the gcmrA87 βGal reporter in heterozygous conditions. By 24hrs after puparium formation (APF), after the division of the MP, the SUP co-expresses Gcm and Hnt (full arrowheads in Fig. 3e–e”’)15 and some MP can still be seen co-expressing Lz and βGal (empty arrowheads in Fig. 3e–e”’). At 48 hrs and 72 hrs APF, three types of cells can be identified: the LEC expressing exclusively Lz, the cells expressing Hnt and low levels of Gcm, which comprise the SC (Fig. 3f”’), and the BC expressing Gcm and almost no Hnt (Fig. 3f,g). Few apoptotic AC can also be detected, expressing Hnt (Fig. 3f”’). This confirms that Gcm and Lz are transcribed in the MP and that Gcm remains expressed in the SUP and its offspring.

Finally, in the adult spermatheca, cell-specific immunolabelling on animals carrying the gcmGal4 driver and the UAS-mCD8GFP reporter (gcm > GFP, Supplemental Figures S3a, S3c–c”) and anti-βgal labelling on the enhancer trap line gcmrA87 in heterozygous conditions (Supplemental Figure S3b) indicate that Gcm is expressed exclusively in the adult BC. These are the cells that undergo apoptosis14 (Supplemental Figures S3c–c”), as shown by the decreased number of labelled cells in old gcm > GFP spermathecae compared to young ones (Supplemental Figures S3d–e’). Of note, the number of BC decreases in the gcm > gcm GOF spermathecae that instead present a very high number of SC (Fig. 2h, Supplemental Figure S3f), suggesting that the BC may convert into SC in gcm > gcm GOF spermathecae.

Collectively, our data show that Gcm starts to be expressed in the MP, specifies SUP differentiation and triggers the differentiation of the SC.

Gcm induces the expression of Hr39 and triggers secretory cell differentiation

Hr39 and Hnt are two transcription factors involved in the development of the spermatheca: knock out as well as KD of hnt and Hr39 lead to defective production of SC in the spermatheca13,14,15. In addition, they both contain canonical Gcm binding sites (GBS)43,44 and were identified as direct targets of Gcm by the genome-wide screen using the DNA adenine methyltransferase identification (DamID) procedure39,45 (Fig. 4a,d). To validate our data functionally, we analysed the regulation of Hnt and Hr39 by Gcm in S2 cells transfected with a Gcm expression vector. The levels of Hr39 transcripts are significantly induced by Gcm (Fig. 4b). Next, we built luciferase reporters carrying the two GBS present in the Hr39 locus where Gcm is binding according to the DamID screen and reporters carrying the mutated GBS. Upon co-transfection with the Gcm expression vector, both GBS present in the Hr39 locus induce luciferase activity and mutations of either GBS reduces the luciferase expression levels (Fig. 4c), indicating that Gcm induces Hr39 expression through these two GBS (Fig. 4a–c). The endogenous levels of Hnt are not significantly induced by Gcm in S2 cells (Fig. 4e), however, the hnt locus possesses one GBS in the promoter region (Fig. 4d) and a luciferase assay similar to that performed on Hr39 indicates a significant induction of hnt reporter expression by Gcm, which decreases upon GBS mutagenesis (Fig. 4f). Thus, Gcm is also able to induce the expression of Hnt through the GBS. The lack of induction of the endogenous Hnt in S2 cells is likely due to the absence of cofactors or to the unavailability of the enhancer region targeted by Gcm. In all cases, the mutation of the GBS does not abolish the induction of the luciferase activity completely. This may be due to an indirect effect of Gcm on these promoters or to the presence of non-canonical GBS. Overall, this data indicate that Gcm promotes Hr39 expression and likely contributes to the induction of Hnt expression as well.

Gcm induces the expression of Hr39 and Hnt.

(a,d) Hr39 (a) and hnt (d) loci in the Drosophila genome (blue rectangles for exons, blue lines for the introns, the arrowheads indicate the orientation). The canonical Gcm binding sites (GBS) are indicated in red and the black histograms indicate the regions targeted by Gcm39. (b,e) Expression levels of Hr39 (b) and hnt (e) measured by qPCR assays in S2 cells transfected with an empty vector (ppacEmpty) or with a vector expressing Gcm (ppacGcm). The levels are relative to those observed upon transfecting the ppacEmpty vector. (c,f) Luciferase assays carried out in S2 cells transfected with ppacEmpty or with ppacGcm and with luciferase vectors carrying the regions covering WT (GBS1 WT and GBS2 WT) or mutated GBS (GBS1 Mut and GBS2 Mut) at the Hr39 locus (c) and the WT or mutated GBS present at the hnt locus (f). (g) Single confocal section of lzGal4,UAS-mCD8GFP/+;UAS-gcmRNAi,UAS-Hr39 (lz > gcm KD,Hr39 GOF) spermatheca from adult female labelled with anti-GFP (lz > GFP, green), anti-Hnt (Hnt, in red) and DAPI (blue). (h) Average number of SC counted in cross-sections of spermathecae of the indicated genotypes. The gcm KD and the gcm KD,Hr39 GOF were driven by lzGal4. The error bars and p-values (b,c,e,f and h) are as described for Fig. 1a. n indicates the number of assays.

Finally, we complemented this data by assessing the biological relevance of the interaction between Gcm and Hr39. Since gcm KD in the MP (lzGal4 driver) leads to a decrease in SC number at adult stage (Fig. 3a,b), we overexpressed Hr39 in lz > gcm KD spermathecae and found rescue of the mutant phenotype (Fig. 4g,h). The increased number of SC in the adult compared to that observed in animals that only express low levels of Gcm strongly suggests that Hr39 is indeed a major target of Gcm in the development of the female reproductive system. Of note, Hr39 is already detected in the genital discs of the late 3rd instar larvae13,14 suggesting that the role of Gcm is not to initiate Hr39 expression but to maintain or increase Hr39 expression during the first division of the MP after pupal formation.

The orthologs of Gcm regulate mNR5A1 expression and are expressed in the mouse uterus

The closest mammalian orthologs of the Hr39 gene are Nr5a1 and Nr5a2, which code respectively for SF-113 and LRH-114 and are both involved in the formation and function of mammalian reproductive tissues46,47,48. We hence assessed whether the functional conservation includes the regulation of Nr5a1 and Nr5a2 by the orthologs of Gcm: mGCM1 and mGCM2. First, we measured the endogenous levels of hNR5A1 and hNR5A2 in HeLa cells (human) and those of mNR5A1 and mNR5A2 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) upon transfection of mGCM1 and mGCM2 expression vectors. While the levels of expression of hNR5A2/mNr5a2 are not modulated by the mGCM proteins, the expression levels of the hNR5A1/mNr5a1 transcripts significantly increase when either mGCM proteins are expressed (Fig. 5a–e). In HeLa cells, both mGCM1 and mGCM2 induce hNR5A1 expression at similar levels (Fig. 5a) and in MEF, mGCM2 induces mNR5A1 expression at higher levels than mGCM1 (9-fold increase compared to WT with mGCM1 versus 6E5-fold increase with mGCM2) (Fig. 5b,c). Then, quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses indicate that mGcm1, mGcm2 and mNr5a1 are expressed in the adult mouse uterus and that their levels of expression in this tissue are higher than those found in liver and testes (Fig. 5f). It is important to note, however, that their levels are one order of magnitude lower than the transcription factor Msx1, which is known to be strongly active in the uterus49 (Fig. 5f). In situ hybridisation assays confirm the expression of mGcm2 mostly in the stroma of the endometrium (Fig. 5g). No signal could be detected using the mGcm1 probe, likely due to the low levels of mGcm1 expression it that tissue. This suggests that the regulation of Hr39 expression by Gcm observed in Drosophila is conserved in evolution and that mGCM proteins might regulate the expression of mNR5A1 in the mouse uterus.

The mGCM proteins induce the expression of the Hr39 ortholog in mammals.

(a,d) Expression levels of hNR5A1 (in black (a)) and hNR5A2 (in grey (d)) in HeLa cells transfected with an empty vector (Control), an expression vector for mGCM1 (+mGCM1) or an expression vector for mGCM2 (+mGCM2), measured by qPCR. (b,c,e) Expression levels of mNr5a1 (in black, (b,c) and mNr5a2 (in grey, (e)) in MEF cells transfected with an empty vector (Control) or with an expression vectors for mGCM1 or mGCM2, measured by qPCR. The y-axis is in log10 scale in (c) and the error bars and p-values are as described for Fig. 1a. n indicates the number of assays. (f) Expression levels of mGcm1, mGcm2, mNr5a1 and that of the transcription factor Msx1 in mouse liver, testes and uterus measured by qPCR. The levels are relative to the house-keeping genes Actb and Gapdh. Each experiment was carried out on three mice. The error bars represent s.e.m. and the y-axis is in log10 scale. (g,g’) In situ hybridisation on adult mouse uterus section targeting mGcm2 using anti-sense mGcm2 probe (g) and negative control using the sense mGcm2 probe (g’). Scale bar represents 50 μm, the stroma (St) of the endometrium corresponds to the area indicated by a dashed line and Ep indicates the columnar epithelium.

Mammalian GCM proteins have been associated with DNA demethylation at the promoter of their target genes: hGCM1 affects Syncytin 2 demethylation in human placenta50 and mGCM1 and mGCM2 affect Hes5 demethylation in the mouse embryo29. For this reason, it was proposed that mGCM proteins trigger DNA demethylation, even though the molecular mode of action was not understood. To further characterize the impact of the mGcm genes, we asked whether mNR5A1 regulation by mGCM1 and mGCM2 is associated with changes in the DNA methylation profile of the mNr5a1 gene using transfected cells. In human and mouse, the Nr5a1 genes contain a CpG island that covers the transcription start site (TSS) until the 3rd exon (Fig. 6a). The methylation rate of each CpG within the regions covering the 2nd exon and the TSS was estimated by bisulfite sequencing in MEF transfected with an empty vector (Control) or with expression vectors of mGCM1 or mGCM2. The three CpG located around the TSS are demethylated in the presence of mGCM1 or mGCM2 proteins compared to that observed upon transfecting the control plasmid (Fig. 6b). In addition, a significant increase in CpG methylation is observed in the exon 2 region upon mGCM1 or mGCM2 transfection (Fig. 6c). The highest levels of methylation are observed when the cells are transfected with mGCM2 (Fig. 6c), in agreement with the strong increase in mNr5a1 expression levels observed in MEF cells overexpressing mGCM2 (Fig. 5e). These data show that the mGCM proteins are not specifically involved in DNA demethylation and fit with the emerging view that gene expression is linked to DNA demethylation at the promoter and to DNA hypermethylation in the gene body51 (Fig. 6d). Our data are also in line with the recent hypothesis that transcription factors can bind demethylated as well as methylated DNA52. Finally, the high levels of expression of hNR5A1/mNR5A1 observed in endometriotic tissues are also linked to high levels of CpG methylation around exon 2 and low levels around the TSS53,54,55,56.

mGCM1 and mGCM2 regulate the methylation profile of mNr5a1.

(a) Schematic representation of the mNr5a1 locus in the mouse genome. The gene is represented as in Fig. 4a. The genomic coordinates of the locus (genome version mm10) are indicated above the gene. The CpG island is highlighted in green, the rectangles within the CpG island indicate the analysed regions in exon 2 and at TSS. (b) Methylation rate for each CpG 30 nucleotides before the TSS and 10 nucleotides after the TSS. The methylation rate in MEF transfected with an empty vector (Control) is indicated in grey, the methylation rate in MEF transfected with an expression vector for mGCM1 is in red and for mGCM2 in blue. Dots above the grey line indicate CpG hypermethylation and dots below indicate CpG hypo-methylation compared to the control cells. (c) Box plot representing the distribution of the methylation rate in the CpG island of mNr5a1 in MEF cells transfected with an empty vector (Control), an expression vector for mGCM1 (+mGCM1) or for mGCM2 (+mGCM2)). The methylation rates were measured for the 51 CpG contained in the exon 2 area highlighted in (a) using bisulfite sequencing. The p-values were estimated using paired student test (see materials and methods) and are represented as described in Fig. 1a. (d) Schematic representation of the impact of the mGCM protein family on the DNA methylation profile of mNr5a1.

Overall, this data suggest that the mGcm genes induce the transcription of mNr5a1 and this is associated with important changes in the DNA methylation profile at the mNr5a1 locus.

Discussion

In this study, we discover a molecular cascade required in the Drosophila female reproductive system that may be conserved in mammals. The Drosophila transcription factor Gcm is expressed during the development of the SC of the spermatheca and mutations or knock-down of Gcm inhibit the development of these cells, leading to female sterility. Gcm acts by targeting the ortholog of the hNR5A1/mNR5A1 hormone receptor Hr39. Finally, the orthologous genes mGcm1 and mGcm2 are expressed in the mouse uterus, induce the expression of hNR5A1/mNR5A1 in human and murine cell lines, respectively and modify the DNA methylation profile of mNr5a1. This suggest that defects in the hGCM pathway may be associated with pathologies affecting women reproductive system.

Common and tissue-specific features of the Gcm pathways

Gcm is required in the nervous, in the immune and in the reproductive systems. These Gcm dependent pathways display a common feature as, in all cases, a multipotent precursor gives rise to cells with different identities. In the nervous system, the neuroblast can produce glia or neurons, in the immune system the prohemocyte can produce plasmatocytes or crystal cells and in the spermatheca the MP can produce SC or LEC. Gcm is absolutely required to induce one fate over the other as gcm mutant animals lack glia and display supernumerary neurons24,30,31 and the number of plasmatocyte decreases whereas that of the crystal cells increases36,38. In the spermatheca, the absence of SC in homozygous gcmGal4 animals is accompanied by an increase in LEC number (Fig. 2h, Supplemental Figure S4), suggesting that Gcm induces the differentiation of the SC at the expense of the LEC.

A second common feature between the three developmental events is the transient and early expression of Gcm. In the spermatheca, Gcm is expressed during the differentiation of the SC but no longer present in the adult SC. Similarly, Gcm is expressed early in the glial and in the hemocyte lineages but its transcripts are not detected in the mature cells34,36,57,58. Thus, the Gcm fate determinant provides a trigger that needs to be erased to allow terminal differentiation. In the nervous system, Gcm activates the transcription of its target gene repo, which remains expressed in glial cells until adulthood59. The Repo homeobox containing protein constitutes the pan-glial specific transcription factor that induces the expression of late glial genes, maintains the glial fate and actually contributes to Gcm degradation57,59 (Trebuchet, unpublished results). In the spermatheca, Gcm induces the expression of the Hr39 transcription factor that is required for SC formation and that remains expressed in those cells until adulthood13,14,15, Hr39 may hence play a maintenance role similar to that played by Repo in the glial cells. Recent data suggest that early and transient expression of fate determinants may be a general rule that allows stable and terminal cell differentiation. Interestingly, the Drosophila proneural transcription factor Atonal (Ato) is expressed early during photoreceptor differentiation but needs to be switched off for normal eye development60.

A third common feature between the three systems is the participation of the Notch pathway. In the spermatheca, the production of the SC from the initial MP encompasses three cells divisions. The first and third divisions involve the Notch pathway and trigger the differentiation of the LEP and the SC respectively14,15. In these two divisions, Notch is activate only in the cells that do not express Gcm suggesting that Notch and Gcm may interact negatively. Such negative interaction was previously reported during the differentiation of the adult sensory organ precursors (SOP). Constitutive activation of the Notch pathway in the SOP represses gcm expression and prevents the production of glial cells; accordingly, lack of Notch induces gcm expression and the production of glia at the expense of neurons61,62. Finally, during the development of the embryonic hemocytes, there is no report of interaction between Gcm and the Notch pathway, however Gcm is involved in plasmatocyte development and Notch in crystal cell development34,36,63. Importantly, several members of the Notch pathway are directly regulated by Gcm including the two ligands Serrate and Delta39, which suggests a strong interaction between Gcm and Notch that remains to be investigated.

Our work also highlights the cell-specific nature of the Gcm differentiation pathways: while the Gcm transcription factor is required to induce several cell identities, its downstream factors are cell-specific. Repo expression is absent in the spermatheca and Hr39 expression is absent in glial cells. Moreover, the overexpression of Gcm in the spermatheca does not activate Repo expression in those cells nor does Gcm overexpression in the embryonic nervous system activate Hr39 expression in that territory (data not shown). Thus, although ‘master regulators’ are considered as simple molecular switches, this represents an oversimplified view of cell differentiation. The activity of such potent transcription factors rather relies on the history of a given cell, that is, its specific transcriptional and epigenetic asset. For example, the ectopic expression of the famous eyeless master gene induces the formation of ectopic eyes on wings, legs and antennae64, while in the embryonic nervous system its ectopic expression alters the axonal wiring of the ventral nerve cord65.

Finally, the expression profile of Gcm gives an important insight on spermatheca differentiation. Our study shows that Gcm and Lz are co-expressed in the MP and that Gcm remains expressed exclusively in the SUP following the asymmetrical division of the MP whereas Lz is repressed in the SUP14. A comparable interaction between Gcm and Lz was observed during the differentiation of the embryonic hemocytes. Gcm is required for the differentiation of the plasmatocytes and Lz for the differentiation of the crystal cells38. Initially, Gcm is expressed in all prohemocytes but subsequently its expression fades away in the precursors of the crystal cells, which allows for the expression of Lz34,37,38. Thus, Gcm induces the plasmatocyte fate and inhibits the crystal cell fate through inhibition of Lz: as mentioned above, gcm mutant animals display supernumerary crystal cells and in addition ectopic Gcm expression in the crystal cell precursors using the lzGal4 driver prevents the expression of Lz and converts cells into plasmatocytes36,38. We propose that in the spermatheca, Gcm is expressed at low levels in the MP where it cohabits with Lz, then its expression progressively rises in the SUP until its levels become sufficient to repress Lz expression in this cell. SUP cells that express low levels of Gcm adopt the LEC fate. The absence of Gcm binding sites at the lz locus and the known role of Gcm as an activator of transcription prompt us to speculate that Gcm represses Lz expression indirectly. The transcriptional repressor Tramtrack (Ttk)66,67 was already described as an inhibitor of Lz expression in the larval eye disc68, is a downstream target of Gcm39,69,70,71 and is expressed in the spermatheca72. Future studies will determine whether Ttk could act as the intermediary protein between Gcm and Lz inhibition.

A conserved role for the Gcm family of proteins in the regulation of Hr39/Nr5a1 and fertility

Hr39 and NR5A1 transcription factors were proposed to share similar functions and to target similar genes for the development of specific secretory glands of the reproductive system (steroidogenic glands in mammals and spermathecae in Drosophila)13,14,73. Our study suggests that the control of Hr39 and NR5A1 by the GCM protein family is also conserved. Gcm controls female fertility due to its effects on the SC in the spermathecae, and the lack of SC is explained by the lack of induction of Hr39. This regulation is conserved in mammals with the mGcm1 and mGcm2 genes inducing mNR5A1 expression in MEF cells and being expressed in the reproductive system. This represents the first evidence of functional conservation for GCM proteins in similar biological systems of Drosophila and mammals.

Endometriosis20,21,22,23,54,74 is an oestrogen-dependent disorder defined by the ectopic growth of endometrium-like tissue (reviewed in ref. 75), which represents the leading cause of women infertility76,77,78. A major feature of endometriotic tissues is the overexpression of hNR5A1 and the modification of the hNR5A1 DNA methylation profile in that tissue: the hNR5A1 TSS is demethylated and the CpG island covering exon 2 is hypermethylated22,53,54,55; the present study shows that mNr5a1 expression and its DNA methylation profile are regulated by the two mGCM proteins (Fig. 6d). This suggests that the GCM protein family could be involved in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Over the past ten years, several studies aimed at identifying the molecular basis of endometriosis by comparing the transcriptomes of healthy endometrium to endometriotic tissue56,79,80,81,82,83,84. hGCM1 and hGCM2 did not come out in any of these studies. The large majority of these reports used micro-array to profile gene expression and both hGCM1 and hGCM2 were below the detection range in all studies even in healthy tissues whereas we detected mGcm1 expression by qPCR and mGcm2 expression by qPCR and in situ hybridisation. Several factors may explain the difficulty to identify the hGCM genes in those analyses, among them the known instability of their RNA and their potential transient expression (reviewed in ref. 85). This indicates that the study of GCM1 and GCM2 in endometriosis should be carried out using highly sensitive methods and possibly during the development of the disease to catch the transient presence of their transcripts.

Overall, our study suggests that the GCM regulatory network is robustly conserved and that Drosophila represents a model of choice to decipher this pathway in the reproductive system. Finally, this study indicates that the Gcm transcription factor has a much broader role than initially thought. We foresee that the deep analysis of its regulatory network will allow us to understand pleiotropic differentiation pathways and hence the role and mode of action of potent fate determinants.

Materials and Methods

Fly strain

Flies were raised on standard medium at 25 °C. The genotype and provenance of the strains are detailed in Supplemental experimental procedures.

Fertility and egg laying assays

Fertility and egg laying assays are detailed in Supplemental experimental procedures. For fertility assays, the progeny produced in 12 days by 3 virgins of the indicated genotypes crossed with one male WT were counted and reported to number of progeny/female. For the egg laying assays, the number of eggs laid in 48 hrs by five females of the indicated genotypes crossed with ten males WT were counted and reported to number of eggs/females/days. The p-values were estimated after variance analysis using bilateral student test with equal variance.

Immunolabelling

The spermathecae were labelled using standard immunolabelling protocol as described in ref. 39. The list of antibodies and the labelling protocol are detailed in in Supplemental experimental procedures.

Secretory cell and basal cell counts

For each spermatheca, the Hnt/DAPI positive cells (SC) were counted from the stack of six focal plans taken at 3 μm interval in the middle of the spermatheca (the plan giving the largest cross-section of the spermatheca). This was repeated in at least six independent spermathecae for each genotype. The average number of SC and the s.e.m. are represented in Figs 2h and 4h. The p-values were estimated as described for the fertility assays.

qPCR and luciferase assay in S2 cells

The transfection of S2 cells, the quantitative PCR (qPCR) and the luciferase assay were performed as described in Cattenoz et al.39 and detailed in Supplemental experimental procedures. Each experiment was carried out in triplicates.

In situ hybridisation and RNA extraction from mouse uterus

RNA in situ hybridisation with digoxigenin-labelled probes for mGcm2 transcripts was performed as described in Vernet et al.86 with slight modifications detailed in Supplemental experimental procedures. The qPCR were carried out on C57BL/6 mouse uterus RNA extracted from 3 different animals with TRI reagent.

Transfection and qPCR in mammalian cells

HeLa cells transfection was performed as described in Cattenoz et al.39 and MEF cells transfection was performed as detailed in Supplemental experimental procedures. 48 hrs after transfection, the cells were sorted according to GFP expression before RNA extraction. Reverse transcription and qPCR were carried out as described for the S2 cells with the primer pairs listed in Supplemental experimental procedures.

Bisulfite sequencing in MEF cells

MEF cells transfected and sorted as described above were used to analyse the methylation profile of mNr5a1 locus. The procedure is detailed in Supplemental experimental procedures. The loci of interest were then amplified by PCR, cloned and sequenced. At least 10 clones were sequenced per condition. The p-values were estimated after variance analysis using bilateral student test for paired samples.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Cattenoz, P. B. et al. An evolutionary conserved interaction between the Gcm transcription factor and the SF1 nuclear receptor in the female reproductive system. Sci. Rep. 6, 37792; doi: 10.1038/srep37792 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Suarez, S. S. & Pacey, A. A. Sperm transport in the female reproductive tract. Hum Reprod Update 12, 23–37, doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi047 (2006).

Scott, M. A. A glimpse at sperm function in vivo: sperm transport and epithelial interaction in the female reproductive tract. Anim Reprod Sci 60, 337–348, doi: 10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00130-5 (2000).

Varner, D. D. Odyssey of the spermatozoon. Asian J Androl 17, 522–528, doi: 10.4103/1008-682x.153544 (2015).

Suarez, S. S. Mammalian sperm interactions with the female reproductive tract. Cell Tissue Res 363, 185–194, doi: 10.1007/s00441-015-2244-2 (2016).

Wilcox, A. J., Weinberg, C. R. & Baird, D. D. Timing of sexual intercourse in relation to ovulation. Effects on the probability of conception, survival of the pregnancy, and sex of the baby. N Engl J Med 333, 1517–1521, doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332301 (1995).

Al-Lawati, H., Kamp, G. & Bienefeld, K. Characteristics of the spermathecal contents of old and young honeybee queens. J Insect Physiol 55, 116–121, doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.10.010 (2009).

Locke, S. J. & Peng, Y. S. The Effects of Drone Age, Semen Storage and Contamination on Semen Quality in the Honey-Bee (Apis-Mellifera). Physiol Entomol 18, 144–148, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3032.1993.tb00461.x (1993).

Pamilo, P. Life-Span of Queens in the Ant Formica-Exsecta. Insect Soc 38, 111–119, doi: 10.1007/Bf01240961 (1991).

Ashrafzadeh, A., Karsani, S. A. & Nathan, S. Mammalian sperm fertility related proteins. Int J Med Sci 10, 1649–1657, doi: 10.7150/ijms.6395 (2013).

O’Flaherty, C. Redox regulation of mammalian sperm capacitation. Asian J Androl 17, 583–590, doi: 10.4103/1008-682x.153303 (2015).

Wolfner, M. F. “S.P.E.R.M.” (seminal proteins (are) essential reproductive modulators): the view from Drosophila. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl 65, 183–199 (2007).

Wolfner, M. F. Precious essences: female secretions promote sperm storage in Drosophila. PLoS Biol 9, e1001191, doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001191 (2011).

Allen, A. K. & Spradling, A. C. The Sf1-related nuclear hormone receptor Hr39 regulates Drosophila female reproductive tract development and function. Development 135, 311–321, doi: 10.1242/dev.015156 (2008).

Sun, J. & Spradling, A. C. NR5A nuclear receptor Hr39 controls three-cell secretory unit formation in Drosophila female reproductive glands. Curr Biol 22, 862–871, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.059 (2012).

Sun, J. & Spradling, A. C. Ovulation in Drosophila is controlled by secretory cells of the female reproductive tract. Elife 2, e00415, doi: 10.7554/eLife.00415 (2013).

Lee, Y. K. & Moore, D. D. Liver receptor homolog-1, an emerging metabolic modulator. Front Biosci 13, 5950–5958 (2008).

Zhang, D. et al. Dysfunction of Liver Receptor Homolog-1 in Decidua: Possible Relevance to the Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia. PLoS One 10, e0145968, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145968 (2015).

El-Khairi, R. & Achermann, J. C. Steroidogenic factor-1 and human disease. Semin Reprod Med 30, 374–381, doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1324720 (2012).

Parker, K. L. & Schimmer, B. P. Steroidogenic factor 1: a key determinant of endocrine development and function. Endocr Rev 18, 361–377, doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0301 (1997).

Attar, E. et al. Prostaglandin E2 via steroidogenic factor-1 coordinately regulates transcription of steroidogenic genes necessary for estrogen synthesis in endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94, 623–631, doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1180 (2009).

Noel, J. C. et al. Steroidogenic factor-1 expression in ovarian endometriosis. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 18, 258–261, doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181c06948 (2010).

Xue, Q. et al. Transcriptional activation of steroidogenic factor-1 by hypomethylation of the 5′ CpG island in endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92, 3261–3267, doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0494 (2007).

Zeitoun, K., Takayama, K., Michael, M. D. & Bulun, S. E. Stimulation of aromatase P450 promoter (II) activity in endometriosis and its inhibition in endometrium are regulated by competitive binding of steroidogenic factor-1 and chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor to the same cis-acting element. Mol Endocrinol 13, 239–253, doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0229 (1999).

Vincent, S., Vonesch, J. L. & Giangrande, A. Glide directs glial fate commitment and cell fate switch between neurones and glia. Development 122, 131–139 (1996).

Hashemothosseini, S. & Wegner, M. Impacts of a new transcription factor family: mammalian GCM proteins in health and disease. J Cell Biol 166, 765–768, doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406097 (2004).

Schreiber, J. et al. Placental failure in mice lacking the mammalian homolog of glial cells missing, GCMa. Molecular and Cellular Biology 20, 2466–2474, doi: 10.1128/Mcb.20.7.2466-2474.2000 (2000).

Thomee, C. et al. GCMB mutation in familial isolated hypoparathyroidism with residual secretion of parathyroid hormone. J Clin Endocr Metab 90, 2487–2492, doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2450 (2005).

Hashemolhosseini, S. et al. Restricted expression of mouse GCMa/Gcm1 in kidney and thymus. Mech Develop 118, 175–178, doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00239-3 (2002).

Hitoshi, S. et al. Mammalian Gcm genes induce Hes5 expression by active DNA demethylation and induce neural stem cells. Nat Neurosci 14, 957–964, doi: 10.1038/nn.2875 (2011).

Hosoya, T., Takizawa, K., Nitta, K. & Hotta, Y. glial cells missing: a binary switch between neuronal and glial determination in Drosophila. Cell 82, 1025–1036 (1995).

Jones, B. W., Fetter, R. D., Tear, G. & Goodman, C. S. glial cells missing: a genetic switch that controls glial versus neuronal fate. Cell 82, 1013–1023 (1995).

Paladi, M. & Tepass, U. Function of Rho GTPases in embryonic blood cell migration in Drosophila. J Cell Sci 117, 6313–6326, doi: 10.1242/jcs.01552 (2004).

Soustelle, L. & Giangrande, A. Novel gcm-dependent lineages in the postembryonic nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 236, 2101–2108, doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21232 (2007).

Bernardoni, R., Vivancos, V. & Giangrande, A. glide/gcm is expressed and required in the scavenger cell lineage. Dev Biol 191, 118–130 (1997).

Jacques, C., Soustelle, L., Nagy, I., Diebold, C. & Giangrande, A. A novel role of the glial fate determinant glial cells missing in hematopoiesis. Int J Dev Biol 53, 1013–1022, doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082726cj (2009).

Bataille, L., Auge, B., Ferjoux, G., Haenlin, M. & Waltzer, L. Resolving embryonic blood cell fate choice in Drosophila: interplay of GCM and RUNX factors. Development 132, 4635–4644, doi: 10.1242/dev.02034 (2005).

Alfonso, T. B. & Jones, B. W. gcm2 promotes glial cell differentiation and is required with glial cells missing for macrophage development in Drosophila. Developmental Biology 248, 369–383, doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0740 (2002).

Lebestky, T., Chang, T., Hartenstein, V. & Banerjee, U. Specification of Drosophila hematopoietic lineage by conserved transcription factors. Science 288, 146–149 (2000).

Cattenoz, P. B. et al. Functional Conservation of the Glide/Gcm Regulatory Network Controlling Glia, Hemocyte, and Tendon Cell Differentiation in Drosophila. Genetics 202, 191–219, doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.182154 (2016).

Mayhew, M. L. & Merritt, D. J. The morphogenesis of spermathecae and spermathecal glands in Drosophila melanogaster. Arthropod Struct Dev 42, 385–393, doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2013.07.002 (2013).

Lane, M. E. & Kalderon, D. Genetic investigation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase function in Drosophila development. Genes Dev 7, 1229–1243 (1993).

Evans, C. J. et al. G-TRACE: rapid Gal4-based cell lineage analysis in Drosophila. Nat Methods 6, 603–605, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1356 (2009).

Miller, A. A., Bernardoni, R. & Giangrande, A. Positive autoregulation of the glial promoting factor glide/gcm. The EMBO journal 17, 6316–6326, doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6316 (1998).

Ragone, G. et al. Transcriptional regulation of glial cell specification. Dev Biol 255, 138–150 (2003).

van Steensel, B. & Henikoff, S. Identification of in vivo DNA targets of chromatin proteins using tethered dam methyltransferase. Nature biotechnology 18, 424–428, doi: 10.1038/74487 (2000).

Luo, X. R., Ikeda, Y. Y. & Parker, K. L. A Cell-Specific Nuclear Receptor Is Essential for Adrenal and Gonadal Development and Sexual-Differentiation. Cell 77, 481–490, doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90211-9 (1994).

Ozisik, G., Achermann, J. C. & Jameson, J. L. The role of SF1 in adrenal and reproductive function: insight from naturally occurring mutations in humans. Mol Genet Metab 76, 85–91, doi: 10.1016/S1096-7192(02)00032-X (2002).

Duggavathi, R. et al. Liver receptor homolog 1 is essential for ovulation. Gene Dev 22, 1871–1876, doi: 10.1101/gad.472008 (2008).

Pavlova, A., Boutin, E., Cunha, G. & Sassoon, D. Msx1 (Hox-7.1) in the adult mouse uterus: cellular interactions underlying regulation of expression. Development 120, 335–345 (1994).

Liang, C. Y. et al. GCM1 Regulation of the Expression of Syncytin 2 and Its Cognate Receptor MFSD2A in Human Placenta. Biol Reprod 83, 387–395, doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.083915 (2010).

Jones, P. A. The DNA methylation paradox. Trends Genet 15, 34–37, doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(98)01636-9 (1999).

Zhu, H., Wang, G. & Qian, J. Transcription factors as readers and effectors of DNA methylation. Nature reviews. Genetics, doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.83 (2016).

Xue, Q., Zhou, Y. F., Zhu, S. N. & Bulun, S. E. Hypermethylation of the CpG Island Spanning From Exon II to Intron III is Associated With Steroidogenic Factor 1 Expression in Stromal Cells of Endometriosis. Reprod Sci 18, 1080–1084, doi: 10.1177/1933719111404614 (2011).

Dyson, M. T. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis predicts an epigenetic switch for GATA factor expression in endometriosis. PLoS Genet 10, e1004158, doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004158 (2014).

Xue, Q. et al. Methylation of a Novel CpG Island of Intron 1 Is Associated With Steroidogenic Factor 1 Expression in Endometriotic Stromal Cells. Reprod Sci 21, 395–400, doi: 10.1177/1933719113497283 (2014).

Yamagata, Y. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling in cultured eutopic and ectopic endometrial stromal cells. PLoS One 9, e83612, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083612 (2014).

Flici, H. et al. Interlocked loops trigger lineage specification and stable fates in the Drosophila nervous system. Nat Commun 5, 4484, doi: 10.1038/ncomms5484 (2014).

Laneve, P. et al. The Gcm/Glide molecular and cellular pathway: new actors and new lineages. Dev Biol 375, 65–78, doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.12.014 (2013).

Halter, D. A. et al. The Homeobox Gene Repo Is Required for the Differentiation and Maintenance of Glia Function in the Embryonic Nervous-System of Drosophila-Melanogaster. Development 121, 317–332 (1995).

Quan, X. J. et al. Post-translational Control of the Temporal Dynamics of Transcription Factor Activity Regulates Neurogenesis. Cell 164, 460–475, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.048 (2016).

Umesono, Y., Hiromi, Y. & Hotta, Y. Context-dependent utilization of Notch activity in Drosophila glial determination. Development 129, 2391–2399 (2002).

Van de Bor, V. & Giangrande, A. Notch signaling represses the glial fate in fly PNS. Development 128, 1381–1390 (2001).

Lebestky, T., Jung, S. H. & Banerjee, U. A Serrate-expressing signaling center controls Drosophila hematopoiesis. Genes Dev 17, 348–353, doi: 10.1101/gad.1052803 (2003).

Halder, G., Callaerts, P. & Gehring, W. J. Induction of ectopic eyes by targeted expression of the eyeless gene in Drosophila. Science 267, 1788–1792 (1995).

Kammermeier, L. et al. Differential expression and function of the Drosophila Pax6 genes eyeless and twin of eyeless in embryonic central nervous system development. Mech Dev 103, 71–78 (2001).

Read, D. & Manley, J. L. Alternatively spliced transcripts of the Drosophila tramtrack gene encode zinc finger proteins with distinct DNA binding specificities. The EMBO journal 11, 1035–1044 (1992).

Tang, A. H., Neufeld, T. P., Kwan, E. & Rubin, G. M. PHYL acts to down-regulate TTK88, a transcriptional repressor of neuronal cell fates, by a SINA-dependent mechanism. Cell 90, 459–467 (1997).

Siddall, N. A., Hime, G. R., Pollock, J. A. & Batterham, P. Ttk69-dependent repression of lozenge prevents the ectopic development of R7 cells in the Drosophila larval eye disc. BMC Dev Biol 9, 64, doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-64 (2009).

Egger, B. et al. Gliogenesis in Drosophila: genome-wide analysis of downstream genes of glial cells missing in the embryonic nervous system. Development 129, 3295–3309 (2002).

Freeman, M. R., Delrow, J., Kim, J., Johnson, E. & Doe, C. Q. Unwrapping glial biology: Gcm target genes regulating glial development, diversification, and function. Neuron 38, 567–580 (2003).

Altenhein, B. et al. Expression profiling of glial genes during Drosophila embryogenesis. Dev Biol 296, 545–560 (2006).

Chintapalli, V. R., Wang, J. & Dow, J. A. T. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nature genetics 39, 715–720, doi: 10.1038/ng2049 (2007).

Val, P., Lefrancois-Martinez, A. M., Veyssiere, G. & Martinez, A. SF-1 a key player in the development and differentiation of steroidogenic tissues. Nucl Recept 1, 8, doi: 10.1186/1478-1336-1-8 (2003).

Chen, P., Wang, D. B. & Liang, Y. M. Evaluation of estrogen in endometriosis patients: Regulation of GATA-3 in endometrial cells and effects on Th2 cytokines. J Obstet Gynaecol Res, doi: 10.1111/jog.12957 (2016).

Bulun, S. E. Mechanisms of Disease Endometriosis. New Engl J Med 360, 268–279, doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804690 (2009).

Lessey, B. A., Lebovic, D. I. & Taylor, R. N. Eutopic endometrium in women with endometriosis: ground zero for the study of implantation defects. Semin Reprod Med 31, 109–124, doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1333476 (2013).

Missmer, S. A. et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol 160, 784–796, doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh275 (2004).

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive, M. Endometriosis and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 98, 591–598, doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.031 (2012).

Kopelman, A. et al. Analysis of Gene Expression in the Endocervical Epithelium of Women With Deep Endometriosis. Reprod Sci, doi: 10.1177/1933719116638179 (2016).

Yamagata, Y. et al. Retinoic acid has the potential to suppress endometriosis development. J Ovarian Res 8, 49, doi: 10.1186/s13048-015-0179-6 (2015).

Aghajanova, L. & Giudice, L. C. Molecular evidence for differences in endometrium in severe versus mild endometriosis. Reprod Sci 18, 229–251, doi: 10.1177/1933719110386241 (2011).

Borghese, B. et al. Gene expression profile for ectopic versus eutopic endometrium provides new insights into endometriosis oncogenic potential. Mol Endocrinol 22, 2557–2562, doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0322 (2008).

Sherwin, J. R. et al. Global gene analysis of late secretory phase, eutopic endometrium does not provide the basis for a minimally invasive test of endometriosis. Hum Reprod 23, 1063–1068, doi: 10.1093/humrep/den078 (2008).

Burney, R. O. et al. Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology 148, 3814–3826, doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1692 (2007).

Cattenoz, P. B. & Giangrande, A. New Insights in the Clockwork Mechanism Regulating Lineage Specification: Lessons From the Drosophila Nervous System. Dev Dynam 244, 332–341, doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24228 (2015).

Vernet, N. et al. Retinoic acid metabolism and signaling pathways in the adult and developing mouse testis. Endocrinology 147, 96–110, doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0953 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Papin, I. Stoll, N. Vernet, Y. Yuasa, G. Aiello, R. Sakr, C. Albrecht, N. Di Iacovo and the Imaging Center of the IGBMC for technical assistance and Y. Yuasa, V. Dasari and N. Di Iacovo for critical reading of the manuscript. Stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) and FlyORF as well as antibodies obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank were used in this study. This work was supported by INSERM, CNRS, UDS, Hôpital de Strasbourg, ARC, INCA and ANR grants. P. Cattenoz was funded by the ANR and W. Bazzi by the USIAS and FRM (FDT20160435111). The IGBMC was also supported by a French state fund through the ANR labex. This study was supported by the grant ANR-10-LABX-0030-INRT, a French State fund managed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche under the frame program Investissements d'Avenir ANR-10-IDEX-0002-02.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G. and P.B.C. conceived and designed the experiments. P.B.C., C.D. and W.B. performed the experiments. A.G. and P.B.C. analysed the data. A.G. and P.B.C. wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cattenoz, P., Delaporte, C., Bazzi, W. et al. An evolutionary conserved interaction between the Gcm transcription factor and the SF1 nuclear receptor in the female reproductive system. Sci Rep 6, 37792 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37792

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37792

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.