Abstract

The two histone deacetylases (Hdacs), Hdac1 and Hdac2, are erasers of acetylation marks on histone tails, and are important regulators of gene expression that were shown to play important roles in hematological malignancies. However, several recent studies reported opposing tumor-suppressive or tumor-promoting roles for Hdac1 and Hdac2. Here, we investigated the functional role of Hdac1 and Hdac2 using the Eμ-myc mouse model of B cell lymphoma. We demonstrate that Hdac1 and Hdac2 have a pro-oncogenic role in both Eμ-myc tumorigenesis and tumor maintenance. Hdac1 and Hdac2 promote tumorigenesis in a gene dose-dependent manner, with a predominant function of Hdac1. Our data show that Hdac1 and Hdac2 impact on Eμ-myc B cell proliferation and apoptosis and suggest that a critical level of Hdac activity may be required for Eμ-myc tumorigenesis and proper B cell development. This provides the rationale for utilization of selective Hdac1 and Hdac2 inhibitors in the treatment of hematological malignancies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Histone deacetylases (Hdacs) belong to a family of 18 enzymes that remove acetylation marks on lysine residues of histone and non-histone proteins1. Hdacs modify the epigenome through deacetylation of histone proteins, thereby inducing chromatin condensation leading to transcriptional repression2,3. They also act on an increasing number of non-histone substrates, nuclear or cytoplasmic, and therefore impact on multiple cellular functions4,5. Human Hdacs (HDACs) have been reported to have altered function and expression (usually overexpressed) in a wide range of human cancers6,7,8,9 and have been considered attractive pharmacological targets for cancer therapy. HDAC inhibitors (HDACis) have potent antitumor activity in hematological and solid malignancies, mainly by inducing apoptosis, inhibiting cell cycle progression and cellular differentiation10,11. Currently, four pan-HDACis, (targeting class I and/or class II HDACs12) are approved for the treatment of T cell lymphoma and multiple myeloma13,14,15,16 and several others are in clinical trials for various cancers, including B cell malignancies (reviewed by9). However, it is unclear which HDAC isoforms are crucial for tumor cell growth and/or survival, and whether selective HDAC inhibition might have comparable therapeutic benefit with less toxicity compared with broad-spectrum HDACis2,17.

Although the two class I Hdacs, Hdac1 and Hdac2, have been shown to be implicated in proliferation of cancer cells and to play an important role in hematological malignancies9,18,19,20,21,22,23, their exact functions in the different cancer types remains elusive. Hdac1 has been shown to have opposing tumor-suppressive as well as tumor-promoting functions in tumorigenesis and in tumor maintenance, respectively24. Numerous studies in different cell types, including B cells, demonstrated that these two enzymes have largely redundant functions during normal development and malignant transformation25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Some studies reported a dose-dependent function of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in some cell types, including T cells and epidermal cells33,34.

In view of these observations, we assessed the functional role of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in the development and progression of Eμ-myc driven B cell lymphomas. Eμ-myc transgenic (tg) mice overexpress the c-myc oncogene in B lymphocytes and develop multicentric lymphomas associated with leukemia35,36,37. We investigated the impact of B lymphocyte-specific deletions of combination of Hdac1 and Hdac2 alleles using targeted conditional deletion with the mb1-cre recombinase30 in Eμ-myc mice. Here, we show that Hdac1 and Hdac2 have tumor-promoting roles in both Eμ-myc tumorigenesis and tumor maintenance. This study reveals that Hdac1 and Hdac2 have a gene dose-dependent pro-oncogenic role in Eμ-myc tumorigenesis, with a predominant role of Hdac1.

Results

Hdac1 and 2 have no tumor suppressor functions in B cells

Previous studies reported that T cell-32,33 and epidermal cell-34 specific ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 alleles unexpectedly leads to spontaneous tumor formation. Therefore, we first investigated whether ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in B cells also induces tumor development. For this we generated B cell-specific deletions of different combinations of Hdac1 and Hdac2 alleles in vivo (Supplementary Figure 1A) and monitored mice for tumor development over a period of 300 days by the Kaplan-Meyer (KPLM) method. Interestingly, in contrast to previous observations in T cells, ablation of Hdac1 and/or Hdac2 in B cells did not lead to spontaneous tumor development (Fig. 1A). Eμ-myc tg mice were used as controls and developed tumors as expected (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Figure 2D). We then performed histopathological analysis from the mice lacking Hdac1 and/or Hdac2 to verify the absence of malignant phenotypes. Consistent with the absence of visible and palpable tumors in the KPLM analysis, we did not detect any pathological signs in Hdac1 and/or Hdac2 KO mice at 8, 20, and even 40 weeks in the spleen, lymph nodes, or thymus (Fig. 1B). Taken together, our results indicate that Hdac1 and Hdac2 do not have a tumor suppressor function in B cells.

Hdac1 and Hdac2 have no tumor suppressor function in B cells.

(A) KPLM tumor-free survival curves for 15 age-matched mice are shown with indicated genotypes. Eμ-myc tg mice are shown as control. Mice were monitored over a period of 300 days for tumor onset and sacrificed when they reached termination criteria (see Material and Methods). (B) Table summarizing histopathological analysis from spleen and lymph nodes of Hdac1 and/or Hdac2 KO mice with indicated genotypes at 8, 20, and 40 weeks. n = 4–10 as indicated, N.A. for not analyzed.

Eμ-myc tumorigenesis is Hdac1 and Hdac2 gene dose-dependent

We next investigated the effect of Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation in the Eμ-myc cancer background, and in particular whether they have tumor suppressive or tumor promoting functions during Eμ-myc tumorigenesis. We previously reported that concomitant ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in non-transformed B cells induced a cell cycle block and apoptosis30. We therefore hypothesized that similar ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 might also have this effect in malignant Eμ-myc tg B cells which overexpress the strong c-myc oncogene. We crossed mice with B cell-specific deletions of different combinations of Hdac1 and Hdac2 alleles with Eμ-myc mice in order to obtain mice having the Eμ-myc tg in different backgrounds with respect to Hdac1 and Hdac2 (Supplementary Figure 2A). Eμ-myc mice overexpressed the c-myc oncogene in all B lymphocytes, as expected (Supplementary Figure 2B,C), and developed multicentric lymphomas (Supplementary Figure 2D), as previously reported35,36,37. We then monitored tumor-free survival by KPLM analysis in mice having different combinations of Hdac1 and Hdac2 alleles. Interestingly, we observed that mono-allelic expression of Hdac2 in Hdac1-deficient Eμ-myc B cells (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+) resulted in delayed tumor development, whereas complete Hdac1 and Hdac2 deletion (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ) prevented tumorigenesis altogether (Fig. 2A). We observed a gradual decrease in tumor incidence and concomitant gradual increase in mean overall survival upon deletion of combinations of Hdac1 and Hdac2 alleles (Fig. 2B). Importantly, these findings demonstrate that Hdac1 and Hdac2 have pro-oncogenic roles in tumorigenesis of Eμ-myc mice, in contrast to other cancer models such as acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL)24. These findings further indicate that Eμ-myc tumorigenesis is Hdac1 and Hdac2 gene dose-dependent. We observed that a critical level of Hdac1 and Hdac2 is required for tumorigenesis. Moreover, Hdac1 and Hdac2 are not completely redundant; we observed that Hdac1 functions as the dominant protein (Fig. 2A,B).

Eμ-myc tumorigenesis is Hdac1 and Hdac2 gene dose-dependent.

(A) Kaplan-Meier tumor-free survival curves are shown for 15 age-matched mice with indicated genotypes. The log-rank test was used to determine the level of significance between curves in the KPLM plots. Significant differences between genotypes are indicated, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. N.S., not statistically significant. (B) Tumor incidence (%; upper panel), and mean overall survival (days; lower panel), according to indicated Hdac1 and Hdac2 genotypes. Bar plots show values extracted from panel A.

Complete Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation prevents Eμ-myc tumorigenesis

The foregoing findings demonstrate that complete Hdac1 and Hdac2 deletion (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ) prevents tumorigenesis (Fig. 2). To determine how the lack of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in B cells impacts Eμ-myc tumorigenesis, we analysed 8-week old mice by first measuring spleen weight, since Eμ-myc mice typically have splenomegaly. We found that only complete ablation of both enzymes (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ), but not ablation of either Hdac1 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2+/+) or Hdac2 (Hdac1+/+; Hdac2Δ/Δ) alone, prevented spleen enlargement (Fig. 3A). We next performed histopathological analysis from spleen (Fig. 3B). As expected, some Eμ-myc mice displayed high grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (HG-NHL, roughly corresponding to Burkitt’s lymphoma in humans), as described previously35,38. Importantly, no Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ Eμ-myc mice had HG-NHL in spleen and lymph nodes, whereas ablation of either Hdac1 or Hdac2 alone did not prevent HG-NHL development (Fig. 3B, table). We next measured circulating peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) using an automated blood cell analyzer. Eμ-myc mice had significantly elevated PBL compared to control wild-type mice (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, we observed that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ Eμ-myc mice had significantly lower PBL counts, compared to control Hdac1+/+; Hdac2+/+ Eμ-myc mice, and hence reduced leukemia burdens (Fig. 3C). Ablation of Hdac1 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2+/+), but not Hdac2 (Hdac1+/+; Hdac2Δ/Δ) in Eμ-myc mice, significantly reduced PBL counts at 8 weeks (Fig. 3C). However, this phenotype is transient, since we did not see any effect in PBL counts in older (10 and 20 week old) Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2+/+ Eμ-myc mice (Supplementary Figure 4). Hence, we conclude that ablation of Hdac1 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2+/+) alone has no major impact on Eμ-myc tumorigenesis. Finally, we performed an analysis of the bone marrow (BM) of Eμ-myc mice by flow cytometry. We performed immunofluorescence stainings with B cell-surface-marker-specific antibodies including B220, IgM, CD19 and CD25 to identify the different B cell populations in the BM (Fig. 3D). Eμ-myc mice displayed blasts at the Pro/PreB cell stage that dominates the BM, as previously reported39. Consistent with the data outlined above, ablation of Hdac1 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2+/+) or Hdac2 (Hdac1+/+; Hdac2Δ/Δ) alone had no effect (Fig. 3E,F). However, ablation of both Hdac1 and Hdac2 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ) prevented the appearance of such Eμ-myc-induced B cell blasts at the Pro/PreB stage (B220+; IgM−; Fig. 3E), more specifically at the PreBII cell stage (B220+;CD19+;CD25+; Fig. 3F). Altogether, these results indicate that ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ) prevents Eμ-myc tumorigenesis. However, quantification of flow cytometric analysis revealed that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ Eμ-myc mice had significantly reduced B cell numbers and almost no PreBII cells (Fig. 3G). These findings suggest that the effect of complete Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation on tumorigenesis could be due to a B cell developmental defect at the PreBII cell stage.

Complete Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation prevents Eμ-myc tumorigenesis.

All experiments were performed in 8-week-old mice. (A) Boxplot shows relative spleen weight (% of body weight) of mice with indicated genotypes. p-values were generated using Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test (n = 11). (B) Representative pictures from histopathological analysis of hematoxylin and eosin stained spleen sections of Eμ-myc mice with indicated genotypes and healthy Hdac1+/+; Hdac2+/+ control. Original magnification of 4X and 10X as indicated (left panel). Pathological findings of HG-NHL were scored in spleen and lymph nodes and summarized (table, right panel, n = 10). p-value was calculated using Student unpaired 2-tailed t test. (C) Blood analysis with automated blood analyzer. Percentage (%) of PBL of indicated genotypes (n ≥ 10). p-value calculated with Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test. (D–F) Eμ-myc BM cells from mice with indicated genotypes were stained with B cell surface marker-specific antibodies, including B220, IgM, CD19 and CD25, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Schematic representation of wild-type BM profile: B220/IgM to distinguish between Pro/preB (B220+; IgM−), immatureB (B220low; IgM+), transitional B (B220+; IgM+) and mature B (B220high; IgM+) cells (upper panels). CD19/CD25 to identify PreBII cell subset (B220+;CD19+; CD25+; lover panels). (E) Representative flow cytometry dot plots of B220/IgM staining gated on total BM lymphocytes. Gated regions indicate B cell subsets of interest with frequency in percent. (F) Representative flow cytometry dot plots showing PreBII lymphocytes subsets. (G) Quantification of flow cytometry analysis from (E,F; n = 4–6 biological replicates). Average percentage of B cells (B220+) and PreBII cells represented with s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed with Student unpaired 2-tailed t test. Significant differences in means between genotypes are indicated, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. N.S., not statistically significant.

Conditional ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in Eμ-myc tumor cells delays tumor appearance in vivo

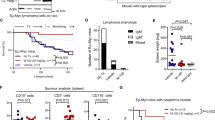

In order to discriminate between indirect B cell developmental defects and direct effects of Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation, we investigating the role of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in existing tumor cells. Therefore, we performed conditional targeted deletion of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in Eμ-myc tumor cells using an in vivo transplantation approach (Fig. 4A). Briefly, syngeneic recipient mice were injected with Eμ-myc lymphoma cells carrying floxed Hdac1 and Hdac2 alleles as well as hormone-inducible cre (Hdac1F/F; Hdac2F/F; Actin-cre ER tg; Eμ-myc tg) and subsequently treated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) to induce deletion of Hdac1 and Hdac2 specifically in transplanted tumor cells. We then performed KPLM tumor-free survival analysis and observed that mice treated with 4-OHT had significantly delayed tumor appearance compared to control mice treated with vehicle (Fig. 4B). Thus, Hdac1 and Hdac2 have a pro-oncogenic role in the Eμ-myc dependent tumor progression. This transplantation assay clearly demonstrates that conditional ablation of both Hdac1 and Hdac2 directly impacts on existing tumor cells and delays tumor appearance.

Conditional ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in Eμ-myc tumor cells delays tumor appearance in vivo.

(A) Experimental workflow scheme for transplantation experiments. Wild-type syngeneic recipient mice were sub-lethally irradiated (350 cGy of whole-body γ-irradiation) and transplanted intra-venously with lymph node-derived tumor cells from Hdac1F/F; Hdac2F/F; Actin-creER tg; Eμ-myc tg mice after development of overt malignancy. Recipient mice were treated with neomycin-supplemented drinking water 1 week before transplantation and up to 2 weeks post transplantation. At two weeks post transplantation, conditional KO was induced in one group of mice by intraperitoneal injection of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT, 5 × 2 mg). Control mice were injected with vehicle. Mice were monitored for tumor onset and sacrificed when they reached termination criteria (see Material and Methods). (B) KPLM tumor-free survival curves of mice transplanted with tumor cells and treated with 4-OHT (n = 6) or vehicle (Ctr, n = 4) are shown. Survival is plotted as days post transplantation. The log-rank test was used to determine the level of significance between curves in the two groups.

Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ delays Eμ-myc tumorigenesis

As shown above, Eμ-myc tumor development was significantly delayed in mice having a single allele of Hdac2 and no Hdac1 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+), while this was not the case in mice with a single allele of Hdac1 and no Hdac2 (Hdac1Δ/+; Hdac2Δ/Δ; Fig. 2). We analysed 8-week old lymphoma-free Eμ-myc mice and first performed flow cytometry analysis of the BM. Interestingly, Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+; Eμ-myc mice had significantly reduced blasts at Pro/PreB cell stages (Fig. 5A, upper panels) and displayed a strongly reduced number of B cells and Pro/PreB cells in the BM (Fig. 5B, upper panels). Furthermore, we found that these mice had several fold increased PreBI cell numbers and similarly decreased PreBII cell numbers (Fig. 5A, lower panels). Quantification revealed significant changes (Fig. 5B, lower panels). We next measured circulating PBL, and observed that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ Eμ-myc mice had significantly lowered PBL counts compared to control Eμ-myc mice with normal levels of Hdac1 and Hdac2 (Fig. 5C). Hence, Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ Eμ-myc mice have reduced leukemia. Taken together, these results indicate that reduction of Hdac2 in absence of Hdac1 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+) impacts Eμ-myc tumorigenesis by reducing the Eμ-myc-induced blasts in the BM, resulting in reduced circulating tumor cells and eventually delays Eμ-myc tumorigenesis (Fig. 2).

Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ Eμ-myc mice have delayed tumorigenesis.

All experiments were performed in 8-week-old lymphoma-free mice. (A,B) BM cells obtained from 8-week old Eμ-myc mice with indicated genotypes were stained with B cell surface marker-specific antibodies, including B220, IgM, CD19 and c-kit, and analyzed by flow cytometry (representative dot plots are shown). (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots gated on total BM lymphocytes. Gated regions indicate B cell subsets of interest with frequency in percent. Pro/preB cell subset (B220+; IgM−) is indicated (red gate, upper panels). Gated PreBI (B220+; c-kit+; CD19+) and PreBII (B220+; CD19+; c-kit−) cell populations are indicated (lower panels). (B) Quantification of flow cytometry analysis with s.e.m. (n = 3 biological replicates). Average percentage of B cells (B220+) and Pro/PreB cells (upper plots), and PreBI and PreBII (lower plots). Statistical analysis was performed with Student unpaired 2-tailed t test. (C) Blood was analyzed with automated blood analyzer. Shown are box plots with frequency (%) of PBL from indicated genotypes (n = 10). p-value calculated with the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test. Significant differences are indicated, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. N.S., not statistically significant.

Hdac1 has a predominant role in non-malignant B cells

In order to test whether the impact of Hdac1 and Hdac2 on B cells is restricted to the Eμ-myc background, we examined mice with B cell-specific deletions of different combinations of Hdac1 and Hdac2 alleles but no Eμ-myc tg (Supplementary Figure 1A). We first examined the effect of Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation in the BM by flow cytometry. We observed that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ but not Hdac1Δ/+; Hdac2Δ/Δ mice had less B cells, whereas Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δmice had a complete block in B cell development (Fig. 6A). Quantification of the flow cytometry analysis revealed that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+, but not Hdac1Δ/+; Hdac2Δ/Δ mice, have higher numbers of PreBI cells and reduced PreBII cell numbers compared to control Hdac1+/+; Hdac2+/+ mice (Fig. 6B). Of note, B cells development was not blocked in Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ mice since these mice still had PreBII cells (Fig. 6C) that could develop throughout all B cells stages and eventually fill the complete pool of mature B cells in the spleen (Supplementary Figure 6). In comparison, mice lacking both Hdac1 and Hdac2 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ) had almost no PreBII cells (Fig. 6C), as shown previously30.

Hdac1 has a predominant role in non-malignant B cells.

All experiments were performed in 8-week-old animals. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots of B220/IgM staining, gated on B220+ lymphocytes derived from BM of mice with indicated genotypes. Gated regions in dot plots indicate B cell subsets of interest with frequency in percent: Pro/preB (B220+; IgM−), ImmatureB (B220low; IgM+), Transitional B (B220+; IgM+) and mature B (B220high; IgM+) cells. (B) Quantification of flow cytometry analysis shown in (A). Bar plots represent average numbers of cells (gated 50,000 lymphocytes) from the different B lymphocyte subsets in the BM. (C) Quantification of flow cytometry analysis shown in (A). Average numbers of absolute PreBII cells. (D) Global Hdac-activity assay performed in CD19+ MACS sorted B cells from BM of mice with indicated genotypes. Values are shown in Relative Fluorescence Units (RFU) relative to control Hdac1+/+; Hdac2+/+ cells. (E) Immunoblot analysis of Hdac1 and Hdac2 expression, and actin as loading control from CD19+ MACS sorted splenic B cells derived from mice with indicated genotypes. The cropped blots originate from a single blot for each protein. The full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Figure 7. All graphs represent mean ± s.e.m. from 3 mice of each genotype. Statistical analysis with Student unpaired 2-tailed t test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. N.S., not statistically significant.

We next determined the effect of Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation on the global Hdac-activity in BM B cells. Interestingly, we observed that progressive ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 alleles generated a B cell-specific gradient of Hdac-activity, with Hdac1 having a greater contribution: Hdac1+/+; Hdac2+/+ = Hdac1+/+; Hdac2Δ/Δ > Hdac1+/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ ≥ Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2+/+ ≥ Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2+/Δ (Fig. 6D). Further assessment by immunoblotting of Hdac1 and Hdac2 protein levels in isolated B cells confirmed that these mice had efficient deletion of Hdac1 and Hdac2 (Fig. 6E). Ablation of Hdac1 resulted in increased Hdac2 protein levels, as shown previously30, while ablation of Hdac2 did not result in increased Hdac1 proteins levels. These results suggest compensatory regulation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 protein levels in B cells, with a predominant compensation of Hdac2 upon loss of the other paralog (Fig. 6E). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Hdac1 also has a predominant role in non-malignant B cells.

Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ impact on proliferation and apoptosis

We previously showed that simultaneous ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ) in non-transformed B cells induced cell cycle arrest and subsequent apoptosis30. These findings prompted us to hypothesize that proliferation and apoptosis might also be affected in Eμ-myc B cells lacking Hdac1 and Hdac2. Therefore, we first investigated the impact of Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation on proliferation of Eμ-myc B cells, by in vivo BrdU labelling experiments. We found that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ Eμ-myc mice had decreased B cell proliferation, as evidenced by reduced BrdU incorporation (Fig. 7A). Quantification of B220+; BrdU+ cells revealed a significant decrease (Fig. 7B). We next investigated whether apoptosis was induced in Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ Eμ-myc B cells, using AnnexinV apoptosis assay by flow cytometry, and indeed observed that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ Eμ-myc B cells underwent apoptosis at higher frequencies than control Hdac1+/+; Hdac2+/+ Eμ-myc B cells (Fig. 7C). Quantification of these data revealed a significant decrease in viable cells (AnnV−;DAPI−), concomitant with a significant increase in apoptotic (AnnV+;DAPI−) and dead cells (AnnV+;DAPI+; Fig. 7D). In summary, B cells with only one allele of Hdac2 have decreased proliferation and undergo apoptosis more frequently. Taken together, our data demonstrate that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ reduces Eμ-myc tumorigenesis by decreasing proliferation and inducing apoptosis.

Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ impact on proliferation and apoptosis.

Experiments were performed in 8-week-old lymphoma-free mice. (A,B) Proliferation analysis by flow cytometry from BM B cells of mice with indicated genotypes injected with BrdU. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots from indicated genotypes. Gated regions indicate B220+; BrdU+ cycling B cells with frequency in percent. (B) Quantification from flow cytometry analysis with mean and s.e.m. of BrdU-positive B cells is shown. (C,D) BM cells isolated from Hdac1+/+; Hdac2+/+ and Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ Eμ-myc mice and stained with Annexin V, DAPI and B cell surface markers for flow cytometry analysis. (C) Representative flow cytometry dot plots from apoptosis assay: viable B cells (P5; annexinV− DAPI−), apoptotic B cells (P6; annexinV+ DAPI−) cells, and dead cells (P7; annexinV+ DAPI+). (D) Quantification of figure (C). Mean percentages and standard deviations are shown. All statistical analysis were performed with the Student unpaired 2-tailed t test. Significant differences in means between genotypes are indicated, *p < 0.05.

Discussion

In this study, we used targeted conditional deletion of Hdac1 and Hdac2, to investigate the functional role of these enzymes in the Eμ-myc murine B cell lymphoma model. Our data reveal a predominant role of Hdac1 in both Eμ-myc tg B cells and non-malignant B cells. We demonstrate that Hdac1 and Hdac2 have a gene dose-dependent pro-oncogenic role in Eμ-myc tumorigenesis with a predominant role of Hdac1. Our results highlight the tumor-promoting role of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in both Eμ-myc tumorigenesis and tumor maintenance.

In accordance with our previous study with young B cell-specific Hdac1 and/or Hdac2 KO mice30, we show here that Hdac1 and Hdac2 do not have a tumor suppressor function in B lymphocytes of old mice (Fig. 1). Indeed, we found that ablation of Hdac1 and/or Hdac2 in non-malignant B cells did not lead to spontaneous tumor development, in contrast to T cells32,33, and epidermal cells34, in which Hdac1 and Hdac2 were reported to act as tumor suppressors. One plausible interpretation of this apparent discrepancy between our data and these previous studies could be a cell type-specific role of Hdac1 and Hdac2.

We further investigated the function of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in the Eμ-myc murine B cell lymphoma model. In accordance with previous reports using HDACis in B lymphoid cancer models9,10,11, we demonstrated using genetic ablation that Hdac1 and Hdac2 have pro-oncogenic roles during Eμ-myc tumorigenesis (Fig. 2). Interestingly, these findings differ from previous studies using a skin tumor model34, or APL24, in which Hdac1 (but not Hdac2) was reported to act as a tumor suppressor during tumorigenesis. This divergence supports the idea that tumor type- or oncogene-specific effects may be decisive. Moreover, we previously observed that Hdac1 and Hdac2 have partly different target preferences30, suggesting that they might regulate different set of genes in a cell type-specific manner.

We further show that complete deletion of both Hdac1 and Hdac2 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ) prevents Eμ-myc tumorigenesis, whereas ablation of either Hdac1 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2+/+) or Hdac2 (Hdac1+/+; Hdac2Δ/Δ) had no effect (Fig. 2). In line with this, we found that absence of these two Hdacs prevents Eμ-myc splenomegaly, HG-NHL occurrence, reduces leukemia, and stops B cell blasts accumulation, which otherwise dominates the BM of Eμ-myc mice (Fig. 3). Thus, ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 prevents tumorigenesis already in the BM by preventing Eμ-myc-induced blasts at early B cell stage. This is in agreement with our earlier report in non-transformed B cells, where ablation of Hdac1 and Hdac2 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ) using Mb1-cre induced a cell cycle block and apoptosis at the PreBII cell stage30. However, the non-inducible Mb1-Cre system does not allow proper discrimination between indirect B cell developmental defects and direct effects of Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation in Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ Eμ-myc mice. We therefore used two different approaches to investigate the direct effect of Hdac1 and Hdac2: i) the use of mice with only one allele of Hdac2 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+), which do not have this block in B cell development to study the tumorigenesis and ii) a transplantation approach allowing conditional deletion of Hdac1 and Hdac2 (using inducible CreERT) in existing tumor cells and test the effect of Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation on tumor maintenance. Our transplantation experiment (Fig. 4) clearly demonstrates that conditional ablation of both Hdac1 and Hdac2 has a direct impact on existing tumor cells, since we observed significantly delayed tumor appearance. Interestingly, we observed that Hdac1 and Hdac2 are not deleted in tumors arising in 4-OHT treated transplanted mice (Supplementary Figure 5), suggesting that the delayed tumor growth observed represents cells that have escaped deletion of Hdac1 and Hdac2. From these findings we conclude that the partial effect we observed after 4-OHT treatment of transplanted recipient mice (Fig. 4) can be explained by incomplete elimination of Hdac1 and Hdac2 using the tamoxifen inducible CreERT system. Our findings demonstrate that loss of Hdac1 and Hdac2 has a direct impact on Eμ-myc tg B cells and demonstrate a critical pro-oncogenic role of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in Eμ-myc tumor progression.

Eμ-myc mice with a single allele of Hdac2 and no Hdac1 (Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+), but not with a single allele of Hdac1 in absence of Hdac2 (Hdac1+/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ), exhibited delayed tumor development (Fig. 2). This demonstrates that Eμ-myc tumorigenesis is Hdac1 and Hdac2 gene dose-dependent, and identifies a predominant role of Hdac1. We further observed that Hdac1 has a predominant role also in non-malignant B cells (Fig. 6). Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ mice, but not Hdac1+/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ mice, had a reduction in PreBII cell numbers (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, ablation of Hdac1 resulted in a strong increase of Hdac2 protein levels, as previously observed30. Interestingly, this increase in Hdac2 levels was not sufficient to compensate for the absence of Hdac1, indicating partially redundant functions and highlighting the predominant role of Hdac1. Furthermore, we observed that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ B cells had significantly reduced Hdac activity compared to Hdac1+/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ B cells. These data demonstrate the predominant role of Hdac1, and suggest that a critical level of Hdac activity may be required for Eμ-myc tumorigenesis.

Similar to Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/Δ, we found that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ impacted Eμ-myc tumorigenesis by reducing the Eμ-myc-induced blasts at the early preBII cell stage in the BM, resulting in reduced circulating tumor cells (Fig. 5). We further investigated whether the impact of Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ in Eμ-myc B cells could be due to proliferation defects and/or apoptosis. Strikingly, we found that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis in Eμ-myc B cells (Fig. 7). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that Hdac1Δ/Δ; Hdac2Δ/+ reduces Eμ-myc-induced blasts in the BM and delays tumorigenesis by decreasing proliferation and inducing apoptosis. Hence, we conclude that Hdac1 and Hdac2 have pro-oncogenic roles in Eμ-myc tumorigenesis. These findings are consistent with earlier studies reporting that complete loss of Hdac1 and Hdac2 induces cell death in proliferating cells, including B and T cells30,32,33. In line with this, Hdac1 and Hdac2 were shown to be the major targets for HDACi-mediated apoptosis induction in leukemic cell lines40. Furthermore, a recent study also showed that ablation of both Hdac1 and Hdac2 decreases proliferation and induces apoptosis in Eμ-myc tumor cells23. Hence, an effect on proliferation and apoptosis upon Hdac1 and Hdac2 ablation could likely explain the delayed tumor appearance in our transplantation experiment (Fig. 4).

Our results describe the pro-oncogenic roles of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in Eμ-myc tumorigenesis and tumor maintenance and support the clinical use of HDACis. Previous studies clearly demonstrated the therapeutic efficacy of pan-HDACis in Eμ-myc lymphomas41,42,43,44,45. Interestingly, we found that human HDAC1, but not human HDAC2, mRNA expression is increased in some Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cancer cell lines and human lymphoma samples, when compared to other cancer cell lines or other human cancer samples, respectively (Supplementary Figure 3). Hence, these data are consistent with our findings outlined above, revealing a predominant role of Hdac1. Our findings demonstrate that Hdac1 can be considered an important factor in Eμ-myc tumorigenesis, and suggest that selective HDAC1 (and HDAC2) inhibitors could be effective for the treatment of BL, as modeled by our preclinical Eμ-myc system, and possibly other hematological malignancies, including some DLBCL. Accordingly, several HDAC1 and HDAC2 isoform-selective inhibitors were recently shown to have in vitro and/or in vivo therapeutic efficacy in pre-clinical models such as Eμ-myc23,42.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that Hdac1 and Hdac2 promote tumor initiation and progression in Eμ-myc mice and that they impact on proliferation and apoptosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing a gene dose-dependent pro-oncogenic role of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in tumorigenesis, with a predominant role of Hdac1. Future research will focus on elucidating the underlying molecular mechanisms by which Hdac1 and Hdac2 regulate proliferation and apoptosis in malignant and non-malignant cells. Our study raises the prospect of using selective HDAC1 and HDAC2 inhibitors for the treatment of BL and other B cell lymphomas with Myc deregulation, with possibly less side effects than pan-HDACis currently used.

Material and Methods

Experimental mice

All experiments were performed in accordance with Swiss federal guidelines for animal experimentation (Art.13a TSchG; Art. 60–62 TSchV) and approved by the FMI Animal committee and the local veterinary authorities (Kantonales Veterinäramt of Kanton Basel-Stadt, permit no. 2384–03). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animal used.

Hdac1F/F; Hdac2F/F conditional knockout (KO) mice have been previously described and characterized30. B lymphocyte-specific deletion of Hdac1 and/or Hdac2 was obtained by crossing Hdac1F/F and Hdac2F/F mice with heterozygote Mb1-cre transgenic (tg) mice30. For transplantation, Actin-Cre ER mice (The Jackson Laboratory; B6.Cg-Tg(CAG-cre/Esr1)5Amc/J) were used to conditionally delete Hdac1 and Hdac2 using tamoxifen. Hdac1 and Hdac2 conditional KO mice were interbred to congenic C57BL/6 heterozygote Eμ-myc tg mice (The Jackson Laboratory; B6.Cg-Tg (IghMyc)22Bri/J)35. All mice were in C57BL/6 genetic backgrounds (backcrossing at least 11 generations). The mice were housed in groups of one to five at 25 °C with a 12:12 h light-dark cycle and received a standard laboratory diet containing 0.8% phosphorus and 1.1% calcium (NAFAG 890, Kliba, Basel, Switzerland) and water ad libitum.

Genotyping PCR

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based genotyping was performed on tail-derived DNA. Mice were genotyped for Hdac1 and Hdac2 conditional alleles as described previously30. The following primer sets were used: Hdac1 flox or WT (forward; 5′-CCTGTGTCATTAGAATCTACTT, and reverse; 5′-GGTAGTTCACAGCATAGTACTT); Hdac1 KO (forward; 5′-GTTACGTCAATGACATCGTCCT, and reverse; 5′-GGTAGTTCACAGCATAGTACTT); Hdac2 flox or WT (forward; 5′-CCCTTTAGGTGTGAGTACAT, and reverse; 5′-rev: AACCTGGAGAGGACAGCAAA); Hdac2 KO (forward; 5′-CCACAGGGAAAAGGAAACAA, and reverse; 5′-AACCTGGAGAGGACAGCAAA). Eμ-myc tg (forward; 5′-TCCAGGGTACATGGCGTATT; and reverse; 5′-TCGGCTGAACTGTGTTCTTG), based on previously published insertion site of c-myc46. Mb1-cre tg (forward; 5′-GGGAAGAAAGAGGCCATAGG; and reverse, 5′-TCCCTCACATCCTCAGGTTC). Actin-Cre tg (forward; 5′-GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC; and reverse, 5′-CAGAGACGGAAATCCATCGCTC). PCRs were performed using the GoTaq Flexi DNA Polymerase Kit (Promega, Cat.M8306) and MJ Mini Thermal Cyclers (BioRad).

RNA isolation and qRT–PCR

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) followed by cDNA synthesis using Improm Reverse Transcriptase (RT) Kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 5–10 ng of cDNA were used to perform Semiquantitative real-time PCR using MESA GREEN qPCR MasterMix Plus for SYBR Assay (Eurogentec) on an ABI PRISM7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosytems). Each reported value is an average of three independent experiments. Relative expression levels were determined by normalizing to gapdh expression using the ΔΔCt method. The following primers were used: for c-myc (forward; 5′-TTTGTCTATTTGGGGACAGTGTT; and reverse; 5′-CATCGTCGTGGCTGTCTG); for Gapdh (forward; 5′-GCCTCGTCCCGTAGACAAAAT; and reverse; 5′-TTCCCATTCTCGGCCTTGA).

Kaplan-Meyer (KPLM) tumor-free survival analysis

Tumor development was monitored every 2–3 days by palpation of cervical, axillary, and inguinal regions for characteristic “water wing” appearance described for Eμ-myc tg mice37. Typically, moribund mice presented with several of the following visible features: enlarged lymph nodes, hunched posture, dyspnea, weight loss, ruffled coats, paralysis, and immobility. Mice were monitored over a period of 300 days for tumor onset and sacrificed when moribund, or reaching tumor-specific endpoints (lymph nodes>1 cm). For moribund mice without tumors, the date of euthanasia was used as the date of death in survival studies. Tumors were isolated, weighted, and prepared for histopathology or protein and RNA extraction. The survival rate was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, using R (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Blood sampling and analysis

Mice were bled at 4 and 8 weeks and blood was collected in EDTA pre-coated tubes. Samples were analyzed utilizing a fully automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex XT-2000i).

Histopathological analysis

Biopsies were formalin-fixed (Shandon Formal-Fixx, Thermo Scientific) for 24 h, dehydrated, paraffin-embedded, cut into 3-μm-thick sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Merck). Pathological analysis was performed according to the Bethesda proposals for classification of lymphoid neoplasms in mice38.

Cell preparation

Single cell suspensions were prepared from BMs by flushing tibia and femur with PBS supplemented with 3% fetal bovine serum. Single-cell suspensions from spleen and lymph nodes were prepared by squeezing splenocytes and lymphocytes from their capsule through a 40-μm nylon mesh of the cell strainer. Peripheral blood was obtained by venous puncture or at autopsy by cardiac puncture. Red blood cells were depleted by lysis in Gey’s solution prior to staining.

Immunofluorescent staining and flow cytometric analysis

Flow cytometry was done according to standard procedures30. The following directly conjugated antibodies were used: anti-CD45R/B220-FITC (clone RA3-6B2), anti-CD25-PE (clone PC61), anti-IgM-APC (clone II/41), anti-IgD-BV605 (clone 11–26 c.2a), were all purchase from BD Biosciences; anti-CD117/c-kit-APC (clone 2B8, eBioscience); and anti-CD19-PE-Cy7 (clone 6D5, Biolegend). All flow cytometry analyses were performed using a multicolor BD LSRII Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Data were analyzed using Flow-Jo (Tree Star) software.

B cell isolation by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS)

Separation of B cells was performed using positive selection with CD19 monoclonal antibodies coupled to magnetic microbeads (anti-CD19 MicroBeads) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (MACS, Miltenyi Biotec). Control flow cytometry from MACS separated cells revealed 95% purity.

In vivo cell cycle analysis by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation

For in vivo BrdU incorporation, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1.5 mg of BrdU solution (10 mg/mL; BD Bioscience) and sacrificed 24 hours later. BrdU staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Bioscience). BM cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of cells in G0/G1-, S-, and G2/M-phases of the cell cycle were determined by manual gating.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptotic lymphocytes were determined using an antibody against AnnexinV conjugated to FITC (AnnexinV apoptosis detection kit, BD Biosciences) and DAPI (Sigma) counterstain, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Percentages of apoptotic cell (FITC+, DAPI−) were determined by manual gating.

Protein extracts and Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested in cold RIPA buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS and protease inhibitors (Roche). Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay, and equal amounts of protein (20 ug) were loaded on 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris Mini Gels (life technologies) separated on SDS–PAGE followed by transfer onto a PVDF transfer membrane (Immobilon-P, Milipore). The following antibodies were used: anti-mouse actin (ab5, Neo Markers), anti-mouse Hdac1 and anti-mouse Hdac2 (provided by Dr. Christian Seiser, Biocenter, Vienna)47. Antibodies were diluted 1:1,000.

In vitro Hdac-activity assay

Global Hdac activity was measured with the Fluor-de-Lys Hdac assay kit (Enzo; BML-KI104-0050) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Fluorescence intensity was detected with Spectromax Gemini plate reader (Molecular Devices).

Eμ-myc lymphoma transplantation

Syngeneic C57BL/6 recipient mice (The Jackson Laboratory; B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) were sub-lethally irradiated (350 cGy whole-body γ-irradiation) using a Rad-source RS2000 irradiator (1.2 Gy/min) and transplanted intra-venously with 2.5 × 105 thawed cryopreserved lymph node-derived tumor cells from Hdac1F/F; Hdac2F/F, Actin-creER tg, Eμ-myc tg donor mice, as previously described36,48. Recipient mice were treated with neomycin-supplemented drinking water (2 mg/ml; sigma) 1 week before, and 2 weeks post transplantation. 14 days post transplantation, conditional KO was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT; 5 × 2 mg). Control mice were injected with vehicle control (ethanol). Mice were monitored for tumor onset and sacrificed when they reached termination criteria as described above.

Oncomine and CCLE database analysis

Human Hdac1 (HDAC1) and human Hdac2 (HDAC2) mRNA expression levels were compared in human tumor samples and human cancer cell lines using the publicly available databases Oncomine (http://www.oncomine.org) and Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE), respectively49,50,51.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (standart error measurement of mean). For all analyses, several independent experiments (N ≥ 3) were carried out. Student’s unpaired 2-tailed t-tests were performed for all analyses using Microsoft Excel. Statistical significance was determined by p values: N.S. p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Statistical analysis of the KPLM survival curves was done using the log-rank test in R (www.r-project.org).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Pillonel, V. et al. Histone deacetylase 1 plays a predominant pro-oncogenic role in Eµ-myc driven B cell lymphoma. Sci. Rep. 6, 37772; doi: 10.1038/srep37772 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Reichert, N., Choukrallah, M. A. & Matthias, P. Multiple roles of class I HDACs in proliferation, differentiation, and development. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS 69, 2173–2187, doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0921-9 (2012).

Dawson, M. A. & Kouzarides, T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell 150, 12–27, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.013 (2012).

Jenuwein, T. & Allis, C. D. Translating the histone code. Science (New York, N.Y.) 293, 1074–1080, doi: 10.1126/science.1063127 (2001).

Choudhary, C. et al. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science (New York, N.Y.) 325, 834–840, doi: 10.1126/science.1175371 (2009).

Glozak, M. A., Sengupta, N., Zhang, X. & Seto, E. Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins. Gene 363, 15–23, doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010 (2005).

Olzscha, H., Sheikh, S. & La Thangue, N. B. Deacetylation of chromatin and gene expression regulation: a new target for epigenetic therapy. Critical reviews in oncogenesis 20, 1–17 (2015).

Mercurio, C., Minucci, S. & Pelicci, P. G. Histone deacetylases and epigenetic therapies of hematological malignancies. Pharmacological research 62, 18–34, doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.02.010 (2010).

Hagelkruys, A., Sawicka, A., Rennmayr, M. & Seiser, C. The biology of HDAC in cancer: the nuclear and epigenetic components. Handbook of experimental pharmacology 206, 13–37, doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-21631-2_2 (2011).

Haery, L., Thompson, R. C. & Gilmore, T. D. Histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases in B- and T-cell development, physiology and malignancy. Genes & cancer 6, 184–213 (2015).

Falkenberg, K. J. & Johnstone, R. W. Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors in cancer, neurological diseases and immune disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov 13, 673–691, doi: 10.1038/nrd4360 (2014).

West, A. C. & Johnstone, R. W. New and emerging HDAC inhibitors for cancer treatment. The Journal of clinical investigation 124, 30–39, doi: 10.1172/jci69738 (2014).

Bantscheff, M. et al. Chemoproteomics profiling of HDAC inhibitors reveals selective targeting of HDAC complexes. Nat Biotech 29, 255–265 (2011).

Ghobrial, I. M. et al. Results of a phase 2 trial of the single-agent histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat in patients with relapsed/refractory Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood 121, 1296–1303, doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-439307 (2013).

Richardson, P. G. et al. PANORAMA 2: panobinostat in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed and bortezomib-refractory myeloma. Blood 122, 2331–2337, doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-481325 (2013).

San-Miguel, J. F. et al. Phase Ib study of panobinostat and bortezomib in relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 31, 3696–3703, doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.7068 (2013).

Rasheed, W., Bishton, M., Johnstone, R. W. & Prince, H. M. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in lymphoma and solid malignancies. Expert review of anticancer therapy 8, 413–432, doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.3.413 (2008).

Ononye, S. N., van Heyst, M., Falcone, E. M., Anderson, A. C. & Wright, D. L. Toward isozyme-selective inhibitors of histone deacetylase as therapeutic agents for the treatment of cancer. Pharmaceutical patent analyst 1, 207–221, doi: 10.4155/ppa.12.21 (2012).

Glaser, K. B. et al. Role of class I and class II histone deacetylases in carcinoma cells using siRNA. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 310, 529–536 (2003).

Haberland, M., Johnson, A., Mokalled, M. H., Montgomery, R. L. & Olson, E. N. Genetic dissection of histone deacetylase requirement in tumor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106, 7751–7755, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903139106 (2009).

Mottet, D. et al. HDAC4 represses p21(WAF1/Cip1) expression in human cancer cells through a Sp1-dependent, p53-independent mechanism. Oncogene 28, 243–256, doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.371 (2009).

Senese, S. et al. Role for histone deacetylase 1 in human tumor cell proliferation. Molecular and cellular biology 27, 4784–4795, doi: 10.1128/mcb.00494-07 (2007).

Wilson, A. J. et al. HDAC4 promotes growth of colon cancer cells via repression of p21. Molecular biology of the cell 19, 4062–4075, doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0139 (2008).

Matthews, G. M. et al. Functional-genetic dissection of HDAC dependencies in mouse lymphoid and myeloid malignancies. Blood 126, 2392–2403, doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-632984 (2015).

Santoro, F. et al. A dual role for Hdac1: oncosuppressor in tumorigenesis, oncogene in tumor maintenance. Blood 121, 3459–3468, doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-461988 (2013).

Montgomery, R. L. et al. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 redundantly regulate cardiac morphogenesis, growth, and contractility. Genes & development 21, 1790–1802, doi: 10.1101/gad.1563807 (2007).

LeBoeuf, M. et al. Hdac1 and Hdac2 act redundantly to control p63 and p53 functions in epidermal progenitor cells. Developmental cell 19, 807–818, doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.015 (2010).

Haberland, M., Carrer, M., Mokalled, M. H., Montgomery, R. L. & Olson, E. N. Redundant control of adipogenesis by histone deacetylases 1 and 2. The Journal of biological chemistry 285, 14663–14670, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081679 (2010).

Ma, P., Pan, H., Montgomery, R. L., Olson, E. N. & Schultz, R. M. Compensatory functions of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC2 regulate transcription and apoptosis during mouse oocyte development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, E481–489, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118403109 (2012).

Montgomery, R. L., Hsieh, J., Barbosa, A. C., Richardson, J. A. & Olson, E. N. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 control the progression of neural precursors to neurons during brain development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106, 7876–7881, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902750106 (2009).

Yamaguchi, T. et al. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 act in concert to promote the G1-to-S progression. Genes & development 24, 455–469, doi: 10.1101/gad.552310 (2010).

Wilting, R. H. et al. Overlapping functions of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in cell cycle regulation and haematopoiesis. The EMBO journal 29, 2586–2597, doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.136 (2010).

Dovey, O. M. et al. Histone deacetylase 1 and 2 are essential for normal T-cell development and genomic stability in mice. Blood 121, 1335–1344, doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-441949 (2013).

Heideman, M. R. et al. Dosage-dependent tumor suppression by histone deacetylases 1 and 2 through regulation of c-Myc collaborating genes and p53 function. Blood 121, 2038–2050, doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-450916 (2013).

Winter, M. et al. Divergent roles of HDAC1 and HDAC2 in the regulation of epidermal development and tumorigenesis. The EMBO journal 32, 3176–3191, doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.243 (2013).

Adams, J. M. et al. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature 318, 533–538 (1985).

Langdon, W. Y., Harris, A. W., Cory, S. & Adams, J. M. The c-myc oncogene perturbs B lymphocyte development in E-mu-myc transgenic mice. Cell 47, 11–18 (1986).

Harris, A. W. et al. The E mu-myc transgenic mouse. A model for high-incidence spontaneous lymphoma and leukemia of early B cells. The Journal of experimental medicine 167, 353–371 (1988).

Morse, H. C. 3rd. et al. Bethesda proposals for classification of lymphoid neoplasms in mice. Blood 100, 246–258 (2002).

Sidman, C. L., Shaffer, D. J., Jacobsen, K., Vargas, S. R. & Osmond, D. G. Cell populations during tumorigenesis in Eu-myc transgenic mice. Leukemia 7, 887–895 (1993).

Inoue, S., Mai, A., Dyer, M. J. & Cohen, G. M. Inhibition of histone deacetylase class I but not class II is critical for the sensitization of leukemic cells to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis. Cancer research 66, 6785–6792, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-05-4563 (2006).

Lindemann, R. K. et al. Analysis of the apoptotic and therapeutic activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors by using a mouse model of B cell lymphoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104, 8071–8076, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702294104 (2007).

Newbold, A. et al. Molecular and biologic analysis of histone deacetylase inhibitors with diverse specificities. Molecular cancer therapeutics 12, 2709–2721, doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-13-0626 (2013).

Newbold, A., Salmon, J. M., Martin, B. P., Stanley, K. & Johnstone, R. W. The role of p21(waf1/cip1) and p27(Kip1) in HDACi-mediated tumor cell death and cell cycle arrest in the Emu-myc model of B-cell lymphoma. Oncogene 33, 5415–5423, doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.482 (2014).

Newbold, A. et al. Characterisation of the novel apoptotic and therapeutic activities of the histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin. Molecular cancer therapeutics 7, 1066–1079, doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-07-2256 (2008).

Ellis, L. et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitors LAQ824 and LBH589 do not require death receptor signaling or a functional apoptosome to mediate tumor cell death or therapeutic efficacy. Blood 114, 380–393, doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-182758 (2009).

Corcoran, L. M., Cory, S. & Adams, J. M. Transposition of the immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer to the myc oncogene in a murine plasmacytoma. Cell 40, 71–79 (1985).

Zupkovitz, G. et al. Negative and positive regulation of gene expression by mouse histone deacetylase 1. Molecular and cellular biology 26, 7913–7928, doi: 10.1128/mcb.01220-06 (2006).

Wall, M. et al. The mTORC1 inhibitor everolimus prevents and treats Emu-Myc lymphoma by restoring oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer discovery 3, 82–95, doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-12-0404 (2013).

Rhodes, D. R. et al. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia (New York, N.Y.) 9, 166–180 (2007).

Rhodes, D. R. et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia (New York, N.Y.) 6, 1–6 (2004).

Barretina, J. et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 483, 603–607, doi: 10.1038/nature11003 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Kohler for help with flow cytometry and cell sorting; S. Bichet for IHC; and C. Seiser for Hdac1 and Hdac2 antibodies. We also thank R.G. Clerc, and M.A. Choukrallah for suggestions on the manuscript. This study was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (no. 31003A-122480 to P.M.) and by the Novartis Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.P. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; N.R. designed and performed experiments at the inception of the project; C.C. provided reagents and technical assistance; M.R.H. and T.Y. contributed to flow cytometry with non-Eμ-myc samples; G.M. contributed technical assistance; A.T. performed histopathological analysis, provided suggestions for experiments and reviewed the manuscript; P.M. supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Pillonel, V., Reichert, N., Cao, C. et al. Histone deacetylase 1 plays a predominant pro-oncogenic role in Eμ-myc driven B cell lymphoma. Sci Rep 6, 37772 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37772

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37772

This article is cited by

-

Epigenetic regulation in hematopoiesis and its implications in the targeted therapy of hematologic malignancies

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2023)

-

Role of HDACs in normal and malignant hematopoiesis

Molecular Cancer (2020)

-

Advances in histone deacetylase inhibitors in targeting glioblastoma stem cells

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2020)

-

Angelica gigas Nakai and Decursin Downregulate Myc Expression to Promote Cell Death in B-cell Lymphoma

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.