Abstract

The relativistic trajectory of a charged particle driven by the Lorentz force is different from the classical one, by velocity-dependent relativistic acceleration term. Here we show that the evolution of optical polarization states near the polarization singularity can be described in analogy to the relativistic dynamics of charged particles. A phase transition in parity-time symmetric potentials is then interpreted in terms of the competition between electric and magnetic ‘pseudo’-fields applied to polarization states. Based on this Lorentz pseudo-force representation, we reveal that zero Lorentz pseudo-force is the origin of recently reported strong polarization convergence to the singular state at the exceptional point. We also demonstrate the deterministic design of achiral and directional eigenstates at the exceptional point, allowing an anomalous linear polarizer which operates orthogonal to forward and backward waves. Our results linking parity-time symmetry and relativistic electrodynamics show that previous PT-symmetric potentials for the polarization singularity with a chiral eigenstate are the subset of optical potentials for the E×B “polarization” drift.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the universal existence of open systems1,2 of non-equilibrium and time-dependent3,4,5 potential energy, the concept of parity-time (PT) symmetry6,7 has become a multidisciplinary topic8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. PT symmetry successfully offers the special form of potentials V(x) = V*(−x), providing physical observables even for non-equilibrium systems. The existence of real observables in PT-symmetric complex potentials has opened the field of non-Hermitian quantum mechanics6,8, which exhibits the phase transition6,16,17 between real and complex eigenspectra in stark contrast to a purely real eigenspectrum observed in Hermitian potentials. By utilizing optical gain- and loss- materials in the refractive index form n(x) = n*(−x), the physics of PT-symmetric potentials has been applied to the exotic control of light flows17,18. The effective realization of PT symmetry has also been extended to acoustics9,13,19, optomechanics10, electronics11, gyrotropic systems20,21, and population genetics12. For all of these fields, critical traits of PT symmetry, e.g. unidirectionality22,23,24, non-Hermitian degeneracy18, and chirality25,26, impose intriguing features on wave dynamics in terms of the ‘singularity’27,28: the coalescence of eigenstates with a chiral form25,26,29,30,31,32 at the exceptional point (EP, or phase transition point)33.

Meanwhile, it is known that relativistic electrodynamics34 for charged particles also exhibits the inherent feature of open systems. The famous relativistic energy expression35, Ẽ = mc2/[1 − (v/c)2]1/2, shows that observers in different frames will see different values of total energy for moving charged particles of velocity v. We note that this non-equilibrium condition results in non-Hermitian form of Hamiltonians, the necessary condition for the achievement of PT symmetry. In the context of the multidisciplinary realization of PT symmetry8,9,10,11,12, therefore, the link between relativistic behaviors of charged particles in electromagnetic fields and wave dynamics in PT-symmetric potentials could offer different viewpoints on the physics of EP singularity in PT-symmetric potentials.

Inspired by the polarization equation of motion from the Schrödinger-like form of Maxwell’s equations36, here we interpret the evolution of optical states of polarizations (SOP) near the EP singularity in direct analogy to the relativistic E×B drift (the movement under orthogonal E and B fields) of charged particles34, which we call the relativistic E×B “polarization” drift of light. The phase transition in PT-symmetric potentials6,16,17 is then understood in view of the competition between electric- and magnetic- ‘pseudo’-fields, and we prove that strong chiral conversion of optical SOP at the EP15,16 corresponds to the accidental cancellation of the Lorentz pseudo-force on the Poincaré hemisphere. By employing this “Lorentz-force picture” in the analysis of the polarization singularity, we then extend the class of the polarization singularity in vector wave equations25,26,37,38,39, revealing the existence of achiral and directional eigenstates at the EP. Our approach paves the way for the unconventional control of optical polarizations, such as anomalous directional polarizers.

Results

Lorentz pseudo-forces for optical polarizations

Consider the planewave propagating along the z-axis of the electrically anisotropic material, with the unity permeability (μ = 1). For the later discussion, we express the arbitrary permittivity tensor in the x-y plane, in terms of Pauli matrices26,31 σ1–3 as ε = (ε2σ1 + ε3σ2 + ε1σ3), or

where εo(z) and ε1−3(z) have slowly-varying complex values, σ1 = [0, 1; 1, 0], σ2 = [0, −i; i, 0], and σ3 = [1, 0; 0, −1]. By applying the spin (x ± iy)/21/2 bases36, Maxwell’s equations become the vector Schrödinger-like equation dψe/dz = Hs·ψe with the temporal-like z-axis40, where the spinor representation of ψe = [ψe+, ψe−]T is the electric field amplitude of (±) optical spin waves ((+) for right-circular polarization (RCP) (x + iy)/21/2, and (−) for left-circular polarization (LCP) (x − iy)/21/2), and Hs is the traceless Hamiltonian expressed with Pauli matrices36,41 as Hs = (ε1σ1 + ε2σ2 + ε3σ3)/(iλ) for λ = 2εo1/2/k0 and the free-space wavenumber k0. If we assign the symmetry axis between x and y axes, the condition of PT-symmetric potentials15,16 requires real-valued εo, ε2, and ε3, and imaginary-valued ε1. Note that imaginary-valued ε1 corresponds to the linear dichroism42,43, the different dissipation for each linear polarization, while real-valued ε2 represents the birefringence. ε3 represents the magneto-optical change of plasma permittivity induced by an external static magnetic field34, and for now, we assume the nonmagnetic case of ε3 = 0.

In this representation, the SOP of light is described by the Stokes parameters44 Sj = ψe†·σj·ψe (j = 0, 1, 2, 3). The change of the SOP can then be expressed in view of light-matter interactions36 by applying the governing equation dψe/dz = Hs·ψe and its conjugate form dψe†/dz = ψe†·Hs†, which leads to the Lorentz pseudo-force equation of motion for the SOP36 (also see Supplementary Note 1)

where Sn = [S1, S2, S3]T/S0 is the pseudo-velocity of the ‘hypothetical’ charged particle corresponding to the SOP of light, and E = 2·Im[ε1, ε2, ε3]T/λ and B = −2·Re[ε1, ε2, ε3]T/λ are the electric and magnetic pseudo-field in relation to imaginary- and real-parts of the permittivity, respectively. Note that Eq. (2) provides direct analogy to the relativistic dynamics of massless charged particles with the motion equation20,22 of ∂tβ = E + β×B −(β·E)β. In this representation of optical polarization states, the acceleration of optical SOP comes from the Lorentz pseudo-force, F ~ dSn/dz (Fig. 1). The first two terms of Eq. (2) are the counterparts of the classical electromagnetic Lorentz force E + β×B, and the 3rd term – (Sn·E)Sn corresponds to the Joule effect34 – (β·E)β in the relativistic equation of motion.

Lorentz pseudo-forces for the acceleration of optical SOP.

Classical (a) magnetic (Sn×B) and (b) electric accelerations (E) on the Poincaré sphere. (c) The acceleration from the relativistic energy variation (−Sn(Sn·E)), originating from the PT-symmetric pseudo-Hermiticity of the Hamiltonian Hs. The corresponding forces F (red arrows) for accelerating positively-charged pseudo-particles (orange spheres) with different pseudo-velocities (or different SOPs, black arrows of Sn) are also shown in (a–c), for Sn = e1, e3, and −e3.

Figure 1a–c shows the effect of each component of the Lorentz pseudo-force on the SOP of propagating light, induced by nonmagnetic PT-symmetric materials (imaginary ε1, real ε2, and zero ε3). While ε2 of the birefringence derives the circulating acceleration on the Poincaré sphere (B = −2ε2·e2/λ, Fig. 1a, Hermitian case), ε1 of the amplification or dissipation results in the linear drift of the SOP (E = 2·Im[ε1]·e1/λ, Fig. 1b, non-Hermitian case). We also note that the energy variation from gain and loss materials Sn·E (Fig. 1c) provides the relativistic nonlinear acceleration of the SOP with respect to E. Consequently, with the orthogonality between pseudo-fields (E⊥B), PT-symmetric potentials naturally satisfy the ideal E×B drift34,45 condition to optical polarization states.

Lorentz force picture on PT symmetry

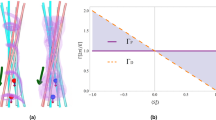

Based on the Lorentz pseudo-force equation of Eq. (2), a phase transition6,16,17 between real and complex eigenspectra in PT-symmetric potentials can be interpreted in terms of the E×B drift34,45: the competition between electric and magnetic pseudo-forces. Figure 2a,b shows the evolution of real and imaginary eigenvalues Δεeig for the Hamiltonian equation dψe/dz = Hs·ψe, as a function of the imaginary potential (εi = Im[ε1], εc = ε2). First, before the EP where eigenvalues are real and non-degenerate (Fig. 2a, εi < εc), the magnetic pseudo-field is larger than the electric pseudo-field, resulting in the counter-directive acceleration of SOP (lower panels in Fig. 2c) to northern-/southern-hemispheres. At the EP with the coalescence (d point in Fig. 2a,b, εi = εc), the equal magnitude of E = 2·εi·e1/λ and B = −2εc·e2/λ fields derives the suppression of total Lorentz pseudo-force on the southern Poincaré sphere, especially with the zero net force at the south pole (Sn = −e3, dSn/dz = E + Sn × B − (Sn·E)Sn = 2·εi·e1/λ + e3 × 2εc·e2/λ = 0, Fig. 2d). It is emphasized that this force cancellation impedes the acceleration near the south pole of the stationary polarization, deriving the SOP convergence to perfect LCP chirality26. After the EP with amplifying and dissipative states (Fig. 2b, εi > εc), the strong electric pseudo-field dominates the motion equation of the SOP, with the co-directive force (lower panels in Fig. 2e) to opposite hemispheres. In the context of electrodynamics analogy, the phase of eigenvalues in PT-symmetric potentials can thus be divided by the (i) B-dominant (before the EP), (ii) B = E (at the EP) and (iii) E-dominant regime (after the EP). It is worth mentioning that the stable point with the stationary polarization can also be obtained at the north pole by changing the sign of εc (converting the fast and slow axes for the birefringence) or εi (converting the gain and loss axes for the linear dichroism), allowing perfect RCP chirality. In terms of this Lorentz pseudo-force representation of SOP, we also note that PT-symmetric potentials15,16 with real-valued ε2 and imaginary-valued ε1 are the special case of the E×B drift with specific field vectors E = 2·εi·e1/λ and B = −2εc·e2/λ, implying the existence of unconventional polarization singularity at other SOPs (e.g. without optical spin) which will be discussed later.

Phases of PT symmetry in terms of the E×B drift.

The evolution of the eigenvalues Δεeig is shown in (a) for their real parts (Re[Δεeig]), and in (b) for imaginary parts (Im[Δεeig]). The Lorentz pseudo-force acceleration for each phase of PT symmetry is shown: (c) before the EP with |B| > |E|, (d) at the EP with |B| = |E|, and (e) after the EP with |B| < |E|. The enlarged plots in (c–e) show the distribution of accelerations near the north and south poles.

E×B polarization drift in PT-symmetric potentials

We then investigate the “evolution” of the SOP, for different pseudo-forces shown in Fig. 2. Figure 3a–c shows the change of the initial SOP of (+, RCP) and (−LCP) spins under different phases of PT symmetry, in relation to the charged particle movement at different phases45 of the relativistic E×B drift (Fig. 3d–f). Because the magnetic pseudo-field dominates the dynamics of SOP before the EP (Fig. 3a,d, |B| > |E|), the SOP for each spin simply rotates around the B field following the Sn×B of Eq. (2). Yet, with different magnitudes of the forces in northern and southern hemispheres (Fig. 2c), the ‘speed’ of the SOP rotation near each pole is different, analogous to different magnetically-gyrating arcs of charged particles in the E×B drift34,45. The directional drift of relativistic particles along the E×B axis (Fig. 3d, toward −S3 axis) is thus reproduced by the slow evolution of SOPs near the Sn = −e3 on the Poincaré sphere (Fig. 3a).

Evolutions of optical SOP in PT-symmetric potentials.

(a–c) The change of the SOP at different phases of PT symmetry: (a) before the EP with |B| > |E|, (b) at the EP with |B| = |E|, and (c) after the EP with |B| < |E|. The corresponding movements of charged particles by the E×B drift are shown in (d–f), respectively. While circles and triangles each denote the incident and final (after 10εo1/2·λo/π) state, orange color is for the initial RCP (or positive spin, Sn = e3), and blue color is for the initial LCP (or negative spin, Sn = −e3). The dotted lines in (a–c) represent the non-relativistic movements of the SOP, without the third term in Eq. (2). The dotted arrows for the LCP and RCP in (d–f) denote the initial movement of each spin.

The extraordinary case of the relativistic E×B polarization drift is achieved at the singular state of EP (Fig. 3b,e), for the case of |B| = |E|. Because of the force cancellation near the perfectly stable south pole (Sn = −e3 for dSn/dz = 0), the (+) spin state converges to the (−) spin when the state approaches the south pole through the gyration by the magnetic pseudo-field (orange line in Fig. 3b), similar to the convergence of the velocity in the motion of relativistic particles (orange line in Fig. 3e). Because the (−) spin state is stationary, we note that the entire SOP, which can be represented in terms of the linear combination of the LCP (−spin) and RCP (+spin), is thus converted to the LCP chiral wave. After the EP (|B| < |E|, Fig. 3c,f), the electric force is dominant, resulting in the linear acceleration mostly towards the direction of E. For all cases, it is noted that the relativistic correction from non-Hermitian Hamiltonians retains the evolution of SOP Sn = [S1, S2, S3]T/S0 on the Poincaré sphere, in contrast to the classical evolutions (dotted lines in Fig. 3a–c) which do not include the third term of Eq. (2).

Realization of achiral and directional singularity

Extending the special case of the E×B polarization drift derived from E = 2·εi·e1/λ and B = −2εc·e2/λ, we now work on other types of E×B polarization drift which allow unconventional polarization singularity without optical spin, by manipulating the direction of electromagnetic pseudo-fields. The vector form of the Lorentz pseudo-force equation provides larger degrees of freedom for the intuitive control of the eigenstate at the singularity, in contrast to the fixed chiral form25,26,29,30,31,32 of scalar PT-symmetric equation. Although the magnetic transition of PT symmetry can also be utilized to achieve the achiral (spin-less) eigenstate at the EP (ε3 ≠ 0, Supplementary Note 2), here we investigate the realization of achiral and directional singularity with the use of nonmagnetic chiral materials. From the constitutive relation including optical chirality46 (or bi-isotropy) D = εE − iχH and B = μH + iχE, the condition of μ = μ0 and diagonal ε with εx ≠ εy represents the nonmagnetic chiral material with general electrical anisotropy, including both birefringence (Re[εx] ≠ Re[εy] for different x- and y-wavevector) and linear dichroism42,43 (Im[εx] ≠ Im[εy] for different x- and y-dissipation). The spin-based Hamiltonian equation dψe/dz = Hs·ψe, for slowly-varying εx = εo + Δε(z) and εy = εo − Δε(z) and constant χ = χo with real-valued εo and χo, derives the Hamiltonian Hs for general chiral materials, in the form of

and k2 = ω2·(μ0εo + χo2) (see Supplementary Note 3 for the general case of spatially-varying χ(z)). The Pauli expression41 of Hs = a1σ1 + a2σ2 + a3σ3 has the coefficients of a1 = −(ik/2)·(Δε/εo), a2 = −(ωχ/2)·(Δε/εo), and a3 = iωχ. The electric and magnetic pseudo-fields for Eq. (2) are then defined as

with the degree of electrical anisotropy ρ = Δε/εo.

Equation (4) proves that the pseudo-field components E(ρ, χ) and B(ρ, χ) driving the SOP are strongly dependent on the type of the anisotropy: birefringence (real ρ) or linear dichroism (imaginary ρ) both satisfying the condition of the E×B drift (E⊥B). For the case of birefringence with E(ρ, χ) = −ωχoρ·e2 and B(ρ, χ) = −kρ·e1 + 2ωχo·e3, the pseudo-field satisfies |E| < |B| in most cases and the condition of |E| ≥ |B| enforces εo < −4χo2/(μ0·ρ2) and thus prohibits the existence of propagating waves at the EP. It is interesting to note that this restriction proves the necessity of complex potentials for obtaining the singularity; therefore we employ linear dichroism for achieving the EP for the propagating wave, by fulfilling the condition of |B| = |E|.

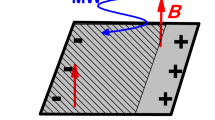

Figure 4 shows the case of linearly-dichroic (ρ = i·ρi) chiral materials, which derive pseudo-fields of E(ρ, χ) = kρi·e1 and B(ρ, χ) = −ωχoρi·e2 + 2ωχo·e3 with the EP condition of ρi2 = 4χo2/(μ0εo) for |B| = |E|. The PT-symmetry-like phase transition (Fig. 4b–d) around the EP (marked with red dots in Fig. 4c,f) occurs in linearly-dichroic chiral materials from the competition between E and B (Fig. 4a), and the direction of the E×B drift is controlled by changing ρi for the pseudo-magnetic field B, allowing the realization of the achiral singularity (Sn ~ −e2 in Fig. 4c); in sharp contrast to the case of PT-symmetric potentials. Furthermore, the obtained EP state has the directionality in its propagation due to the wavevector-dependency of Eq. (4) (Fig. 4b–d vs Fig. 4e–g, Sn ~ e2 in Fig. 4f), which originates from the broken mirror symmetry of chiral materials for forward and backward waves.

Directional EP with the achiral eigenstate in linearly-dichroic chiral materials.

(a) The relative magnitude of electric and magnetic pseudo-fields as a function of material parameters. The Lorentz pseudo-force acceleration for each phase is shown: (b,e) before the EP with |B| > |E|, (c,f) at the EP with |B| = |E|, and (d,g) after the EP with |B| < |E|, for (b–d) forward and (e–g) backward waves. (h) The operation schematic of an anomalous linear polarizer for randomly-polarized incidences: red and blue arrows denote the anisotropic permittivity with the linear dichroism and dotted arrows represent the coupling through optical chirality.

This directionality with achiral designer eigenstate at the EP allows the implementation of unconventional polarizers based on the polarization convergence at the EP. Figure 4h shows an example of the anomalous linear polarizer, operating ‘orthogonal’ to forward and backward waves. While the SOP of forward waves are converged to the +45° linear polarization (Fig. 4c), the SOP of backward waves becomes −45° linear polarization. Moreover, in contrast to the case of classical linear polarizers which perfectly reflect the orthogonally polarized waves (e.g. the y-polarized incidence to the x-polarizer), the linear-polarizing functionality in the structure of Fig. 4h operates for the ‘entire’ SOP due to the non-orthogonality between eigenstates.

Discussion

In summary, we found the link between the seemingly unrelated fields of PT symmetry optics and relativistic electrodynamics. This reinterpretation of PT symmetry brings insight to the singularity in polarization space, broadening the class of parity-time symmetric Hamiltonians in vector wave equations39. The counterintuitive achievement of the achiral and directional EP eigenstate is also demonstrated, which allows the realization of anomalous linear polarizers for randomly polarized incidences. The comprehensible understanding of the EP in terms of the dynamics of charged particles will provide a novel design methodology near the singularity: the generation of chiral waves47,48,49, topological photonics which has focused only on chiral states38, coherent wave dynamics50, PT-symmetry-like potentials based on causality51,52 or supersymmetric optics53,54, and optical analogy of spintronics. At the same time, this classical viewpoint on relativistic electrodynamics also enables the analogy of EP dynamics in charged particle movements, the linear E×B drift toward a single direction for every initial velocity vectors.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yu, S. et al. Acceleration toward polarization singularity inspired by relativistic E×B drift. Sci. Rep. 6, 37754; doi: 10.1038/srep37754 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Weiss, U. Quantum dissipative systems. (World Scientific, 1999).

Demirel, Y. Nonequilibrium thermodynamics: transport and rate processes in physical, chemical and biological systems. (Newnes, 2013).

Hayrapetyan, A. G., Klevansky, S. & Goette, J. B. Instantaneous amplitude and angular frequency modulation of light in time-dependent PT-symmetric optical potentials. arXiv preprint arXiv:1503.04720 (2015).

Nerukh, A., Sakhnenko, N., Benson, T. & Sewell, P. Non-stationary electromagnetics. (CRC Press, 2012).

Hayrapetyan, A. G., Götte, J. B., Grigoryan, K. K., Fritzsche, S. & Petrosyan, R. G. Electromagnetic wave propagation in spatially homogeneous yet smoothly time-varying dielectric media. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 178, 158–166 (2016).

Bender, C. M. & Boettcher, S. Real spectra in non-Hermitian Hamiltonians having PT symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 5243 (1998).

Bender, C. M. Making sense of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians. Rep. Prog. Phys. 70, 947 (2007).

Bender, C. M., Brody, D. C. & Jones, H. F. Complex Extension of Quantum Mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 270401 (2002).

Fleury, R., Sounas, D. & Alù, A. An invisible acoustic sensor based on parity-time symmetry. Nat. Commun. 6, 5905, doi: 10.1038/ncomms6905 (2015).

Lü, X.-Y., Jing, H., Ma, J.-Y. & Wu, Y. PT-Symmetry-Breaking Chaos in Optomechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 253601 (2015).

Ramezani, H., Schindler, J., Ellis, F., Günther, U. & Kottos, T. Bypassing the bandwidth theorem with PT symmetry. Phys. Rev. A 85, 062122 (2012).

Waxman, D. A model of population genetics and its mathematical relation to quantum theory. Contemp. Phys. 43, 13–20 (2002).

Zhu, X., Ramezani, H., Shi, C., Zhu, J. & Zhang, X. PT-symmetric acoustics. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031042 (2014).

Jones-Smith, K. & Mathur, H. Non-Hermitian quantum Hamiltonians with P T symmetry. Phys. Rev. A 82, 042101 (2010).

Bender, C. M. & Klevansky, S. PT-symmetric representations of fermionic algebras. Phys. Rev. A 84, 024102 (2011).

Klaiman, S., Günther, U. & Moiseyev, N. Visualization of branch points in p t-symmetric waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 080402 (2008).

Rüter, C. E. et al. Observation of parity–time symmetry in optics. Nat. Phys. 6, 192–195 (2010).

Zhen, B. et al. Spawning rings of exceptional points out of Dirac cones. Nature 525, 354–358 (2015).

Hayrapetyan, A., Grigoryan, K., Petrosyan, R. & Fritzsche, S. Propagation of sound waves through a spatially homogeneous but smoothly time-dependent medium. Ann. Phys. 333, 47–65 (2013).

Lee, J. et al. Reconfigurable Directional Lasing Modes in Cavities with Generalized PT Symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 253902 (2014).

Li, H., Thomas, R., Ellis, F. & Kottos, T. Four-port photonic structures with mirror-time reversal symmetries. New J. Phys. 18, 075010 (2016).

Lin, Z. et al. Unidirectional invisibility induced by PT-symmetric periodic structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 213901 (2011).

Yu, S., Mason, D. R., Piao, X. & Park, N. Phase-dependent reversible nonreciprocity in complex metamolecules. Phys. Rev. B 87, 125143 (2013).

Yu, S., Piao, X. & Mason, D. R., In, S. & Park, N. Spatiospectral separation of exceptional points in PT-symmetric optical potentials. Phys. Rev. A 86, 031802 (2012).

Lawrence, M. et al. Manifestation of PT Symmetry Breaking in Polarization Space with Terahertz Metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 093901 (2014).

Yu, S., Park, H. S., Piao, X., Min, B. & Park, N. Low-dimensional optical chirality in complex potentials. Optica 3, 1025, doi: 10.1364/OPTICA.3.001025 (2016).

Bendix, O., Fleischmann, R., Kottos, T. & Shapiro, B. Exponentially Fragile PT Symmetry in Lattices with Localized Eigenmodes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 030402 (2009).

Schindler, J., Li, A., Zheng, M. C., Ellis, F. M. & Kottos, T. Experimental study of active LRC circuits with PT symmetries. Phys. Rev. A 84, 040101 (2011).

Dembowski, C. et al. Observation of a chiral state in a microwave cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 034101 (2003).

Heiss, W. & Harney, H. The chirality of exceptional points. Eur. Phys. J. D 17, 149–151 (2001).

Mandal, I. Exceptional points for chiral Majorana fermions in arbitrary dimensions. Europhys. Lett. 110, 67005 (2015).

Mandal, I. & Tewari, S. Exceptional point description of one-dimensional chiral topological superconductors/superfluids in BDI class. Physica E 79, 180–187 (2016).

Heiss, W. D. The physics of exceptional points. Jour. Phys. A 45, 444016 (2012).

Jackson, J. D. Classical electrodynamics. (Wiley, 1998).

Stephani, H. Relativity: An introduction to special and general relativity. (Cambridge university press, 2004).

Kuratsuji, H. & Kakigi, S. Maxwell-Schrödinger equation for polarized light and evolution of the Stokes parameters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1888 (1998).

Kang, M., Liu, F. & Li, J. Effective spontaneous PT-symmetry breaking in hybridized metamaterials. Phys. Rev. A 87, 053824 (2013).

Lu, L., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Topological photonics. Nat. Photon. (2014).

Gear, J., Liu, F., Chu, S., Rotter, S. & Li, J. Parity-time symmetry from stacking purely dielectric and magnetic slabs. Phys. Rev. A 91, 033825 (2015).

Longhi, S. Quantum‐optical analogies using photonic structures. Laser Photon. Rev. 3, 243–261 (2009).

Bandyopadhyay, S. & Cahay, M. Introduction to spintronics. (CRC press, 2008).

Nordén, B. Circular dichroism and linear dichroism. (Oxford University Press, USA, 1997).

Ren, M., Plum, E., Xu, J. & Zheludev, N. I. Giant nonlinear optical activity in a plasmonic metamaterial. Nat. Commun. 3, 833, doi: 10.1038/ncomms1805 (2012).

Teich, M. C. & Saleh, B. Fundamentals of photonics. (Wiley Interscience, 2007).

Takeuchi, S. Relativistic E×B acceleration. Phys. Rev. E 66, 037402 (2002).

Lindell, I. V., Sihvola, A., Tretyakov, S. & Viitanen, A. Electromagnetic waves in chiral and bi-isotropic media. (Artech House Antenna Library, 1994).

Piao, X., Yu, S., Hong, J. & Park, N. Spectral separation of optical spin based on antisymmetric Fano resonances. Sci. Rep. 5, 16585, doi: 10.1038/srep16585 (2015).

Furumi, S. & Tamaoki, N. Glass‐Forming Cholesteric Liquid Crystal Oligomers for New Tunable Solid‐State Laser. Adv. Mater. 22, 886–891 (2010).

Yu, S., Piao, X., Hong, J. & Park, N. Metadisorder for designer light in random systems. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501851, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501851 (2016).

Mrejen, M. et al. Adiabatic elimination-based coupling control in densely packed subwavelength waveguides. Nat. Commun. 6, 7565, doi: 10.1038/ncomms8565 (2015).

Horsley, S., Artoni, M. & La Rocca, G. Spatial Kramers–Kronig relations and the reflection of waves. Nat. Photon. 9, 436–439 (2015).

Yu, S., Piao, X., Yoo, K., Shin, J. & Park, N. One-way optical modal transition based on causality in momentum space. Opt. Express 23, 24997–25008, doi: 10.1364/OE.23.024997 (2015).

Yu, S., Piao, X., Hong, J. & Park, N. Bloch-like waves in random-walk potentials based on supersymmetry. Nat. Commun. 6, 8269, doi: 10.1038/ncomms9269 (2015).

Miri, M.-A., Heinrich, M. & Christodoulides, D. N. Supersymmetry-generated complex optical potentials with real spectra. Phys. Rev. A 87 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) through the Global Frontier Program (GFP, 2014M3A6B3063708) and the Global Research Laboratory Program (GRL, K20815000003), all funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning of the Korean government. S. Yu was also supported by the Basic Science Research Program (2016R1A6A3A04009723), and X. Piao and N. Park were also supported by the Korea Research Fellowship Program (KRF, 2016H1D3A1938069) through the NRF, all funded by the Ministry of Education of the Korean government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. conceived the presented idea. S.Y. and X.P. developed the theory and performed the computations. N.P. encouraged S.Y. to investigate the link between relativistic electrodynamics and non-Hermitian physics while supervising the findings of this work. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, S., Piao, X. & Park, N. Acceleration toward polarization singularity inspired by relativistic E×B drift. Sci Rep 6, 37754 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37754

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37754

This article is cited by

-

Dual-band Circular Polarizer Based on Simultaneous Anisotropy and Chirality in Planar Metamaterial

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.