Abstract

Orderly arrayed granular crystals exhibit extraordinary capability to tune stress wave propagation. Granular system of higher dimension renders many more stress wave patterns, showing its great potential for physical and engineering applications. At nanoscale, one-dimensionally arranged buckyball (C60) system has shown the ability to support solitary wave. In this paper, stress wave behaviors of two-dimensional buckyball (C60) lattice are investigated based on square close packing and hexagonal close packing. We show that the square close packed system supports highly directional Nesterenko solitary waves along initially excited chains and hexagonal close packed system tends to distribute the impulse and dissipates impact exponentially. Results of numerical calculations based on a two-dimensional nonlinear spring model are in a good agreement with the results of molecular dynamics simulations. This work enhances the understanding of wave properties and allows manipulations of nanoscale lattice and novel design of shock mitigation and nanoscale energy harvesting devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Granular materials, due to their intrinsic discreteness, randomness and interaction diversity, exhibit a wide range of distinguished physical phenomena in mechanics, electromagnetism as well as quantum mechanics from macroscale to nanoscale1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The concept of force chain or force network acts as a powerful tool to visualize force (or stress, strain) distribution in solid granular media and bridges granular materials to complex network analysis with the aid of experimental methods such as photoelasticity and computer simulations, inspiring the novel design of stress wave controlling and energy absorption system8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Once orderly arranged, granular materials are able to exhibit unique wave behaviors and extraordinary (sometimes even counterintuitive) ability to tune stress wave thanks to tunable contact nonlinearity18. One-dimensional (1D) homogeneous chain of spherical granules, as the simplest arrangement, has been theoretically, numerically and experimentally proved to be capable of supporting the propagation of strongly nonlinear translational solitary wave19,20,21,22,23 governed by highly nonlinear Hertzian contact24. A solitary wave is a nonlinear dispersionless wave without any temporal evolution in shape and its phase speed is amplitude-dependent. Mathematically, weakly nonlinear solitary waves are the solutions of a class of nonlinear equations such as the Korteweg-de Vries (KdV) equation, sine-Gordon equation as well as the nonlinear Schrödinger equation23,25 and strongly nonlinear Nesterenko solitary wave is a solution of highly nonlinear wave equation first introduced for Hertzian chain by Nesterenko in ref. 19 and for general interaction law in ref. 22. In addition, desired wave behaviors can be obtained by purposely manipulating physical properties of the components of the above-mentioned strongly nonlinear system such as material, shape and size of grains. It makes granular materials a promising candidate for shock disintegration, energy harvesting, nondestructive testing, etc26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Wave properties of coherent tightly packed granular systems in 2D and 3D have also been investigated, for example, 2D square packing, curved channel, Y-shaped packing and ordered granular network43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. Recently, inspired by these macroscopic studies, we have carried out investigations of the counterpart system at nanoscale, and were able to show that 1D arrayed buckyball (C60) system, resembling macroscale spheres, also supports strongly nonlinear Nesterenko solitary wave60. However, this solitary wave is both qualitatively and quantitatively different from that of macroscale system. On one hand, waves in nanoscale system is very sensitive to ambient temperature, which directly determines the level of thermal vibration that is harmful to nanoscale solitary wave propagation. On the other hand, governed by van der Waals interactions instead of the Hertz law in contact mechanics, the force-overlap distance relation of adjacent interacting nanoscale granules exhibits no linear term with a stronger nonlinearity than Hertzian law61, thus leading to a different amplitude-wave speed relation of the strongly nonlinear waves. We have established a semi-empirical nonlinear spring (NS) model to accurately describe nanoscale solitary waves at low temperature (10 K), as a simplification of intermolecular interaction as well as an analogue to Nesterenko solitary wave. Substituting buckyballs with carbon nanotubes (resembling cylindrical or tubal particles), we have demonstrated that 1D single-walled carbon nanotube (SWNT) system serves as a highly effective and reusable energy absorber62. Further, we studied a C60-SWNT hybrid system, having achieved a quantitative tuning of nanoscale solitary waves with good precision63.

In this study, we investigate stress wave behaviors in 2D buckyball system via molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, as an extension of our previous work on 1D nanoscale lattice. As coherent macroscale studies suggest, 2D constructions render more types of wave patterns, suggesting a very promising potential for stress wave-related applications. The presentation of our work is structured as follows. In Sec. 2, we first introduce the setup of investigated system, including the square close packing (scp) and the hexagonal close packing (hcp) system. In Sec. 3, we put forward a theoretical model to describe 2D problem. In Sec. 4, we present the results of MD simulations and numerical calculations based on the 2D NS model of the two packing modes. Finally, in Sec. 5, we present some concluding remarks and possibilities for future investigations.

System descriptions

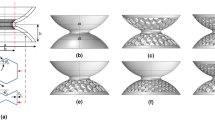

In this study, we investigate two basic 2D uniform packing modes, i.e. scp and hcp, whose coordination numbers64 (or contact numbers) are 4 and 6 respectively and hcp is the densest packing mode possible (with a packing density of ~0.9609), as is illustrated in Fig. 1. In this paper, the size of investigated systems is chosen as 10-order. The shortest distance between two C60 molecules equals to the equilibrium spacing d0 = 10.05Ǻ65, corresponding to the close packing modes. A C60 molecule on one edge away from the corners is selected as an impactor to generate a stress wave with an initial velocity of 2000 m/s, a moderate impacting velocity for studying nanoscale impact dynamics. The impacting direction is determined by an impacting angle θ, defined as the angle between the velocity and the y axis (see Fig. 1). The MD investigation of stress wave behaviors of the system is carried out based on the open-source program LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator)66 and visualized using molecular visualization program VMD (Visual Molecular Dynamics)67. To minimize the disturbance of thermal vibration, the initial temperature is set as T = 10 K and the systems are run for equilibrium in the canonical ensemble (NVT) for 3 ps, which is a sufficient time duration in this study (see Figure S1). Major investigations of wave behaviors are in the micro-canonical ensemble (NVE). More detailed simulation descriptions are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Theoretical modeling

The dynamics of the 2D system is modeled by a 2D NS model, as a dimensional extension of 1D NS model. In this study, the values of both stiffness parameter k and nonlinearity index n are identical to the 1D NS model, whose theoretical background is briefly reviewed in the Supplementary Information. The Hamiltonian of the whole C60 system can be given as follows

where V(r) is the potential function of two interacting C60 molecule with respect to distance r; ui is the displacement vector from the initial position of ith C60 molecule; eij is the unit vector pointing from ith C60 molecule to jth C60 molecule.

In numerical calculations of scp and hcp arrangements all interactions of a C60 molecule with 8 surrounding molecules are taken into consideration (see the regions surrounded by dashed lines in Fig. 1) without any symmetrical or collision mode-related simplifications. It is advantageous over previous numerical methods with respect to calculation precision46,47,48,49,55. The 2D equation of motion of ith C60 can be given as

The numerical calculations are performed using a forth order Runge-Kutta algorithm to integrate the nonlinear ordinary differential equations68. As an initial condition, the displacement vector ui of each C60 equals to zero vector and the velocity vector ui is also zero vector except for the impactor, whose initial velocity is nonzero. The numerical calculation lasts 3000 fs each time.

Results

We choose two impacting angles to study the impact responses of nanoscale lattice, i.e. θ = 0° and θ = 30°. The magnitude of particle velocity is extracted to characterize stress wave propagation. The investigation of wave behaviors in scp and hcp configurations is organized as follows: (a) particle velocity magnitude vM distributions at given instants; (b) particle velocity amplitude vAmp distributions; (c) comparison between MD simulation results and numerical calculation results, i.e. solutions of Eq. (2); (d) Discussions on the unique wave properties in scp and hcp configurations.

Square close packing

Particle velocity magnitude distributions at given instants and particle velocity amplitude distributions of scp configuration under two different impacting angles are presented in Fig. 2.

As is illustrated in Fig. 2, stress wave in scp system is highly directional where the major portion of wave energy transmits through initially excited chains. In fact, waves traveling in initially excited chains are solitary waves, whose shape and wave speed remain constant as they travel (see Figure S2). Later we will show that these solitary waves are in good agreement with Nesterenko’s well-known 1D solitary wave in many aspects. Because of the highly directionality of scp packing modes and the dispersionless characteristics of translational solitary waves, there is potential for scp granular configuration to be applied to stress wave guidance and energy focusing etc.

The comparison between MD simulations and numerical calculations of scp system is shown in Fig. 3, where the time histories of particle velocity magnitude and acceleration on certain direction of 3 representative C60s are compared.

Comparison of particle velocity magnitude vM and acceleration ax(y) between MD simulations and numerical calculations in scp granular configuration for different impacting angles. vM and ax(y) of the C60s in squares are extracted and the colors of the curves and the squares are corresponding. The vertical scale is 5 × 1015 m/s2 and the horizontal scale is 500 fs. (a), (b) and (c) θ = 0°. (d), (e) and (f) θ = 30°. The results of MD simulations and numerical calculations based on the 2D NS model are plotted in solid lines and dashed lines respectively.

According to the comparison in Fig. 3, the results of MD simulations and numerical calculations are in excellent agreement. To confirm that the prediction accuracy of NS model is not sensitive to the position of impactor C60 molecule, another comparison is made where the impactor is chosen as the C60 molecule at the bottom left, as is shown in Figure S3.

A further exploration to the properties of excited solitary waves in 2D scp system is as follows. A set of MD simulations are conducted where the impacting angles range from 0 deg to 75 deg, resulting in a series of solitary waves of various force amplitudes (presented in Table S1) propagating along the C60 chain in the dashed square in Fig. 4. With the theory of 1D NS model (see the Supplementary Information), wave speed can by predicted by inputting wave amplitude and the predicted values match well with simulation results (see Fig. 4). The scaling relation between particle velocity amplitude and wave speed of Nesterenko solitary wave is

where  and thus

and thus  . Fit of the simulation results with Eq. (3) is illustrated in Fig. 4, demonstrating that the investigated system satisfies Eq. (3) very well. In this strongly nonlinear system, the width of the wave (characteristic spatial length) Ln, according to Nesterenko’s theory, can be given as

. Fit of the simulation results with Eq. (3) is illustrated in Fig. 4, demonstrating that the investigated system satisfies Eq. (3) very well. In this strongly nonlinear system, the width of the wave (characteristic spatial length) Ln, according to Nesterenko’s theory, can be given as

where a is the distance between adjacent particles (in our case a = d0). For buckyball system, Eq. (4) outputs Ln≈3a, consistent with the simulation results. It is smaller than 5a in Hertzian chains with very small initial compression due to higher nonlinearity. Above analysis further confirms that this solitary wave obeys Nesterenko’s theory.

Hexagonal close packing

Particle velocity magnitude distributions at given instants and particle velocity amplitude distributions of hcp configuration under two different impacting angles are presented in Fig. 5.

As can be seen, although stress wave propagation in hcp configuration tends to be directional, the amplitude decays as the wave travels and the input energy tends to be distributed. The reason is that in hcp system adjacent row and column will be affected by moving particles regardless of their velocity directions and thus energy is distributed to two or more surrounding particles. This pattern will continue spreading to more and more particles and energy or particle velocity amplitude is gradually decreasing. Therefore, hcp configuration of C60 molecules can serve as a nanoscale protective device.

The comparison between MD simulations and numerical calculations of scp system is shown in Fig. 6.

Comparison of particle velocity magnitude vM and acceleration ax(y) between MD simulations and numerical calculations in hcp granular configuration for different impacting angles.

vM and ax(y) of the C60s in squares are extracted and the colors of the curves and the squares are corresponding. The vertical scale is 5 × 1015 m/s2 and the horizontal scale is 500 fs. (a), (b) and (c) θ = 0°. (d), (e) and (f) θ = 30°. The results of MD simulations and numerical calculations based on the 2D NS model are plotted in solid lines and dashed lines respectively.

Although the agreement between the results of MD simulations and numerical calculations is generally good, it can be observed that there appears a little discrepancy between simulations and model predictions for the velocity and acceleration curves of some selected C60 molecules and it is not surprising due to the atoms vibrating about the equilibrium positions instead of being absolutely static after stress wave passes through. Therefore, the position or time of a C60 molecule when it interacts with other surrounding molecules is actually random. In addition, the parameters of NS model are obtained in 1D system where two degrees of freedom are eliminated, which may not be utterly suitable for 2D situation in this study. Due to error accumulation, the precision of model prediction decreases as the length of the force chain increases, and therefore, precisely predicting the velocity or acceleration of C60 molecule with a complex stress wave path can be fairly difficult. This also explains why the predictions on scp configurations are usually more accurate than hcp configuration on the condition that traveling distances of the stress waves are similar.

To further investigate the wave spreading behavior of nanoscale hcp configuration, a 30° observation line is defined (see the right panel of Fig. 7), along which stress wave propagation is studied. For a θ = 0° impact, the time histories of particle velocity magnitude of C60 molecules on the observation line is extracted and amplitudes of each molecule are marked, as is shown in the left panel of Fig. 7. Previous research on high dimensional-structured granular system tends to model the spreading of wave energy partition as exponentially decay55,56,57. In this study, we fit the particle velocity amplitude in the same manner and the fitting results are satisfactory (see the dashed line in Fig. 7). Moreover, the pulse duration tp on each C60 molecule is subplotted in Fig. 7, showing that as the amplitude decreases, stress wave stays longer on a single C60 molecule.

Concluding Remarks

At macroscale, orderly arranged granular materials have demonstrated its power to tune stress waves. At nanoscale, however, stress wave tuning and manipulations based on discrete granular configurations is a rather unexplored topic. In this work, we studied the 2D problem of nanoscale stress wave propagation as an extension of 1D propagation in buckyball system via MD simulation. We show that scp supports highly directional Nesterenko solitary waves along initially excited chain while hcp attenuates impact exponentially by continuously spreading wave energy to adjacent particles. We are able to describe the wave behaviors of both configurations in a good agreement with a 2D NS model. This work further validates the NS model as a feasible simplification of complicated van der Waals interaction in modeling the stress wave behaviors in nanoscale lattice of higher dimension and suggests the possibilities of 2D nanoscale system acting as energy harvesting, guiding or shock mitigating devices. More types of nanoscale granular configurations and their potential applications will be covered in our future work.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Xu, J. and Zheng, B. Stress Wave Propagation in Two-dimensional Buckyball Lattice. Sci. Rep. 6, 37692; doi: 10.1038/srep37692 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Hinrichsen, H. & Wolf, D. E. The physics of granular media. (Wiley-VCH, 2004).

Aranson, I. S. & Tsimring, L. S. Patterns and collective behavior in granular media: Theoretical concepts. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 641–692, doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.78.641 (2006).

Jop, P., Forterre, Y. & Pouliquen, O. A constitutive law for dense granular flows. Nature 441, 727–730, doi: 10.1038/nature04801 (2006).

Beloborodov, I. S., Lopatin, A. V., Vinokur, V. M. & Efetov, K. B. Granular electronic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 469–518, doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.79.469 (2007).

Xu, K., Qin, L. & Heath, J. R. The crossover from two dimensions to one dimension in granular electronic materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 368–372, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.81 (2009).

Folli, V., Ghofraniha, N., Puglisi, A., Leuzzi, L. & Conti, C. Time-resolved dynamics of granular matter by random laser emission. Sci. Rep. 3, 2251, doi: 10.1038/srep02251 (2013).

Kumar, D. et al. Spreading of triboelectrically charged granular matter. Sci. Rep. 4, 5275, doi: 10.1038/srep05275 (2014).

Liu, C., Nagel, S. R., Schecter, D., Coppersmith, S. & Majumdar, S. Force fluctuations in bead packs. Science 269, 513 (1995).

Coppersmith, S., Liu, C.-h., Majumdar, S., Narayan, O. & Witten, T. Model for force fluctuations in bead packs. Phys. Rev. E 53, 4673 (1996).

Mueth, D. M., Jaeger, H. M. & Nagel, S. R. Force distribution in a granular medium. Phys. Rev. E 57, 3164 (1998).

Makse, H. A., Johnson, D. L. & Schwartz, L. M. Packing of compressible granular materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4160 (2000).

Majmudar, T. S. & Behringer, R. P. Contact force measurements and stress-induced anisotropy in granular materials. Nature 435, 1079–1082, doi: 10.1038/nature03805 (2005).

Peters, J. F., Muthuswamy, M., Wibowo, J. & Tordesillas, A. Characterization of force chains in granular material. Phys. Rev. E 72, 041307, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.041307 (2005).

Vallejo, L. E., Lobo-Guerrero, S. & Chik, Z. In Fractals in Engineering 67–80 (Springer, 2005).

Bassett, D. S., Owens, E. T., Daniels, K. E. & Porter, M. A. Influence of etwork topology on sound propagation in granular materials. Phys. Rev. E 86, 041306, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.041306 (2012).

Kondic, L. et al. Topology of force networks in compressed granular media. Europhys. Lett. 97, 54001, doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/97/54001 (2012).

Wood, D. M. & Leśniewska, D. Stresses in granular materials. Granul. Matter 13, 395–415 (2011).

Porter, M. A., Kevrekidis, P. G. & Daraio, C. Granular Crystals. Phys. Today 68, 44 (2015).

Nesterenko, V. F. Propagation of nonlinear compression pulses in granular media. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 24, 733–743, doi: 10.1007/bf00905892 (1983).

Lazaridi, A. & Nesterenko, V. Observation of a new type of solitary waves in a one-dimensional granular medium. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 26, 405–408 (1985).

Coste, C., Falcon, E. & Fauve, S. Solitary waves in a chain of beads under Hertz contact. Phys. Rev. E 56, 6104–6117 (1997).

Nesterenko, V. F. Dynamics of Heterogeneous Materials. (Springer New York, 2001).

Sen, S., Hong, J., Bang, J., Avalos, E. & Doney, R. Solitary waves in the granular chain. Phys. Rep. -Rev. Sec. Phys. Lett. 462, 21–66, doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2007.10.007 (2008).

Johnson, K. L. Contact mechanics. (Cambridge University Press, 1987).

Drazin, P. G. & Johnson, R. S. Solitons: an introduction. (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

Hong, J. & Xu, A. Nondestructive identification of impurities in granular medium. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 4868–4870, doi: doi: 10.1063/1.1522829 (2002).

Hong, J. Universal Power-Law Decay of the Impulse Energy in Granular Protectors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 108001 (2005).

Doney, R. & Sen, S. Decorated, Tapered, and Highly Nonlinear Granular Chain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 155502 (2006).

Daraio, C., Nesterenko, V. F., Herbold, E. B. & Jin, S. Strongly nonlinear waves in a chain of Teflon beads. Phys. Rev. E 72, 016603 (2005).

Daraio, C., Nesterenko, V. F., Herbold, E. B. & Jin, S. Energy Trapping and Shock Disintegration in a Composite Granular Medium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 058002 (2006).

Daraio, C. & Nesterenko, V. F. Strongly nonlinear wave dynamics in a chain of polymer coated beads. Phys. Rev. E 73, 026612 (2006).

Daraio, C., Nesterenko, V. F., Herbold, E. B. & Jin, S. Tunability of solitary wave properties in one-dimensional strongly nonlinear phononic crystals. Phys. Rev. E 73, 026610 (2006).

Porter, M., Daraio, C., Herbold, E., Szelengowicz, I. & Kevrekidis, P. Highly nonlinear solitary waves in phononic crystal dimers. Phys. Rev. E 77, 1–4 (2008).

Harbola, U., Rosas, A., Romero, A. H., Esposito, M. & Lindenberg, K. Pulse propagation in decorated granular chains: An analytical approach. Phys. Rev. E 80, 051302 (2009).

Fraternali, F., Porter, M. A. & Daraio, C. Optimal Design of Composite Granular Protectors. Mech. Adv. Mat. Struct. 17, 1–19, doi: 10.1080/15376490802710779 (2009).

Carretero-González, R., Khatri, D., Porter, M. A., Kevrekidis, P. G. & Daraio, C. Dissipative Solitary Waves in Granular Crystals. Phys.Rev. Lett. 102, 024102 (2009).

Spadoni, A. & Daraio, C. Generation and control of sound bullets with a nonlinear acoustic lens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 7230–7234 (2010).

Ngo, D., Khatri, D. & Daraio, C. Highly nonlinear solitary waves in chains of ellipsoidal particles. Phys. Rev. E 84, 026610 (2011).

Khatri, D., Ngo, D. & Daraio, C. Highly nonlinear solitary waves in chains of cylindrical particles. Granul. Matter 14, 63–69 (2012).

Ngo, D., Griffiths, S., Khatri, D. & Daraio, C. Highly nonlinear solitary waves in chains of hollow spherical particles. Granular Matter 15, 149–155, doi: 10.1007/s10035-012-0377-5 (2013).

Molerón, M., Leonard, A. & Daraio, C. Solitary waves in a chain of repelling magnets. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 184901, doi: 10.1063/1.4872252 (2014).

Wang, E. et al. High-amplitude elastic solitary wave propagation in 1-D granular chains with preconditioned beads: Experiments and theoretical analysis. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 72, 161–173, doi: 10.1016/j.jmps.2014.08.002 (2014).

Zhu, Y., Shukla, A. & Sadd, M. H. The effect of microstructural fabric on dynamic load transfer in two dimensional assemblies of elliptical particles. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 44, 1283–1303, doi: 10.1016/0022-5096(96)00036-1 (1996).

Matthies, K. & Friesecke, G. Geometric solitary waves in a 2D mass-spring lattice. Discrete and Cont. Dyn. Syst. B 3, 105–144, doi: 10.3934/dcdsb.2003.3.105 (2002).

Nishida, M. & Tanaka, Y. DEM simulations and experiments for projectile impacting two-dimensional particle packings including dissimilar material layers. Granul. Matter 12, 357–368, doi: 10.1007/s10035-010-0173-z (2010).

Leonard, A., Fraternali, F. & Daraio, C. Directional Wave Propagation in a Highly Nonlinear Square Packing of Spheres. Exp. Mech. 53, 327–337, doi: 10.1007/s11340-011-9544-6 (2011).

Leonard, A. & Daraio, C. Stress wave anisotropy in centered square highly nonlinear granular systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 214301, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.214301 (2012).

Leonard, A., Daraio, C., Awasthi, A. & Geubelle, P. Effects of weak disorder on stress-wave anisotropy in centered square nonlinear granular crystals. Phys. Rev. E 86, 031305, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.031305 (2012).

Szelengowicz, I., Kevrekidis, P. G. & Daraio, C. Wave propagation in square granular crystals with spherical interstitial intruders. Phys. Rev. E 86, 061306, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.061306 (2012).

Awasthi, A. P., Smith, K. J., Geubelle, P. H. & Lambros, J. Propagation of solitary waves in 2D granular media: A numerical study. Mech. Mater. 54, 100–112, doi: 10.1016/j.mechmat.2012.07.005 (2012).

O’Donovan, J., O’Sullivan, C. & Marketos, G. Two-dimensional discrete element modelling of bender element tests on an idealised granular material. Granul. Matter 14, 733–747, doi: 10.1007/s10035-012-0373-9 (2012).

Cai, L., Yang, J., Rizzo, P., Ni, X. & Daraio, C. Propagation of highly nonlinear solitary waves in a curved granular chain. Granul. Matter 15, 357–366 (2013).

Szelengowicz, I., Hasan, M. A., Starosvetsky, Y., Vakakis, A. & Daraio, C. Energy equipartition in two-dimensional granular systems with spherical intruders. Phys. Rev. E 87, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.87.032204 (2013).

Yang, J. & Daraio, C. Frequency- and Amplitude-Dependent Transmission of Stress Waves in Curved One-Dimensional Granular Crystals Composed of Diatomic Particles. Exp. Mech. 53, 469–483, doi: 10.1007/s11340-012-9652-y (2013).

Leonard, A., Chong, C., Kevrekidis, P. G. & Daraio, C. Traveling waves in 2D hexagonal granular crystal lattices. Granul. Matter 16, 531–542, doi: 10.1007/s10035-014-0487-3 (2014).

Leonard, A., Ponson, L. & Daraio, C. Wave mitigation in ordered networks of granular chains. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 73, 103–117, doi: 10.1016/j.jmps.2014.08.004 (2014).

Leonard, A., Ponson, L. & Daraio, C. Exponential stress mitigation in structured granular composites. Extreme Mechanics Letters 1, 23–28, doi: 10.1016/j.eml.2014.12.005 (2014).

Manjunath, M., Awasthi, A. P. & Geubelle, P. H. Wave propagation in 2D random granular media. Physica D 266, 42–48, doi: 10.1016/j.physd.2013.10.004 (2014).

Schonberg, W. P., Burgoyne, H. A., Newman, J. A., Jackson, W. C. & Daraio, C. Proceedings of the 2015 Hypervelocity Impact Symposium (HVIS 2015) Guided Impact Mitigation in 2D and 3D Granular Crystals. Procedia Engineering 103, 52–59, doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2015.04.008 (2015).

Xu, J., Zheng, B. & Liu, Y. Solitary Wave in One-dimensional Buckyball System at Nanoscale. Sci. Rep. 6, 21052, doi: 10.1038/srep21052 (2016).

Parsegian, V. A. Van der Waals forces: a handbook for biologists, chemists, engineers, and physicists. (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Xu, J. & Zheng, B. Highly effective energy dissipation system based on one-dimensionally arrayed short single-walled carbon nanotubes. Extreme Mech. Lett., doi: 10.1016/j.eml.2016.09.009 (2016).

Xu, J. & Zheng, B. Quantitative tuning nanoscale solitary waves. Carbon 111, 62–66, doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2016.09.056 (2017).

Conway, J. H. & Sloane, N. J. A. Sphere packings, lattices and groups. Vol. 290, (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Girifalco, L. A., Hodak, M. & Lee, R. S. Carbon nanotubes, buckyballs, ropes, and a universal graphitic potential. Phys. Rev. B 62, 13104–13110 (2000).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Molec. Graphics 14, 33–38, doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 (1996).

DeVries, P. L. & Hasbun, J. E. A first course in computational physics. (Taylor & Francis, 1994).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Beihang University, Startup fund for “Zhuoyue 100” titled professorship, Beihang University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.X. and B.Z. conducted the research and wrote the main manuscript text. B.Z. contributed to the MD simulations and the figure preparation.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, J., Zheng, B. Stress Wave Propagation in Two-dimensional Buckyball Lattice. Sci Rep 6, 37692 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37692

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37692

This article is cited by

-

Influence of interactions between multiple point defects on wave scattering in granular media

Granular Matter (2022)

-

A micromechanics-based micromorphic model for granular materials and prediction on dispersion behaviors

Granular Matter (2020)

-

Reflection and transmission of the incident wave due to impurities in the bead chain

Indian Journal of Physics (2020)

-

Universal design law of equivalent systems for Nesterenko solitary waves transmission

Granular Matter (2020)

-

Wave propagation and pattern formation in two-dimensional hexagonally-packed granular crystals under various configurations

Granular Matter (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.