Abstract

We study magneto-transport properties of several amorphous Indium oxide nanowires of different widths. The wires show superconducting transition at zero magnetic field, but, there exist a finite resistance at the lowest temperature. The R(T) broadening was explained by available phase slip models. At low field, and far below the superconducting critical temperature, the wires with diameter equal to or less than 100 nm, show negative magnetoresistance (nMR). The magnitude of nMR and the crossover field are found to be dependent on both temperature and the cross-sectional area. We find that this intriguing behavior originates from the interplay between two field dependent contributions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Superconducting materials, due to their multiple characteristic length scales, viz.; penetration depth, coherence length and Fermi wavelength, show richer phenomena than other non-superconducting materials, in nanoscale dimension1. The onset of superconductivity is accounted for by nucleation of the superconducting phase shunting the normal current. This effect as observed in superconducting systems, is determined by the temperature dependent coherence length (ξ), irrespective of their dimensionality2. At the low temperature part of the transition, dimensionality plays a crucial role. As soon as, if nothing else, one channel of supercurrent nucleates, in 2D and 3D systems, spots of normal phase do not contribute to zero DC resistance and temperature dependence of resistance has an abrupt bottom part. However, in 1D, where the cross-sectional area, σ ≤ ξ2, there exists only one parallel channel of supercurrent2, phase fluctuations (known as phase slips) lead to a preterm suppression of the superconducting properties. As a consequence, superconducting nanowires are nonlinear elements and are dual to Josephson junctions3 where, the roles of phase and charge, and simultaneously current and voltage, are interchanged. Disorder is also capable to tune and induce new correlated electron physics in low-dimensional materials as observed in a recent work on quasi 1D superconductors4. The study of quasi-one dimensional (1D) superconductors deals with the fundamental question, pointed out by Little5, of whether there exist a superconducting state, or enhanced fluctuations in low-dimension suppress the phase coherence. As the temperature (T) drops below a critical value, TC, the resistance (R) in 1D superconductors drops, but it ceased to go to zero like its bulk counterpart, and a finite R persists6 to the lowest T. The low energy excitations, leading to this residual R, represent a local disturbance of superconductivity for a short period of time. These fluctuations represents activation process which are triggered by either thermal, where the population is strongly T dependent7,8, or through quantum mechanical tunneling, which have a weak T dependence9,10.

Thermal phase slip was accounted well within the theory developed by Langer, Ambegaokar, McCumber, Halperin (LAMH)7,8, and was confirmed by experiments on 0.5 μm tin whiskers6. The interpretation of quantum phase slip was rather complex. Study of such dissipative superconductivity has been a difficult task as the non-equilibrium quasiparticles are massively generated by phase slip process11. If not removed effectively, they tend to overheat the nanowire, driving it into the normal state. Thin MoGe12,13 and Al wires14,15 seem to be switched into the normal state by a single phase slip. In an inhomogeneous superconductor, reentrance16 (switching to insulating state again as T → 0) may occur if the Josephson energy rises with respect to the thermal energy (or the Coulomb energy in granular materials). Thermal and quantum phase slips were also observed in narrow junction of Al, fabricated by controlled electromigration17. Quantum phase slip phenomenon was also observed in ultranarrow superconducting nanorings18 and Josephson junction ring19. In superconductor nanoring18, the phenomenon is responsible for suppression of persistent current, another basic attribute of superconductivity. It has been shown that QPS significantly affect their magnitude, the period and the shape of the current-phase relation. There have also been some ambiguities in T-dependence of R for superconducting wires. Long R tail was absent in Pb wires as narrow as 15 nm20 and the system went to a ‘true superconducting state’ however, narrow Al wires exhibit the long R tail21. Alternatively, in case of previously studied amorphous Indium oxide nanowires22, some wires showed vanishing R at low- T, and some saturated at a non-zero value. For titanium nanowires of effective diameter of the order of 50 nm, QPS has significantly broaden the R(T)23. Similar type of broadened transition and R plateau was previously observed in MoGe nanowires and attributed to quantum phase slips24. Also a recent work on indium oxide nanowires25 showed flattening of R as T is decreased and attributed it’s occurrence to a possible macroscopic quantum mechanical tunneling of vortices between pinning sites. While going from a 2D to a quasi- 1D system, TC is found to be decreased in case of amorphous MoGe films as the width is reduced and superconductivity was completely destroyed in the 1D limit26. A recent work suggested that decrease in TC follows exponential variation with the inverse of the wires’ cross-sectional area27.

In superconductors, application of B enhance the superconducting fluctuations through two effects, by aligning electron spins and by increasing the kinetic energy of the electrons via Meissner screening current28 and as a result R increase with B. Nonetheless, in narrow superconducting strips of Pb29 and Al21, at small magnetic fields, negative magnetoresistance (nMR) is observed. Out of several non-mutually-exclusive theoretical pictures of nMR30,31,32, no commonly accepted model for this phenomenon has been found yet and has been an open question in 1D superconductivity33.

In this paper, we present the results of low- T magneto transport measurements on a series of amorphous Indium oxide (a:InO) nanowires. Pronounced nMR in nanowires of width less than or equal to 100 nm, irrespective of length, has been observed. The magnitude of nMR is found to have a size and T dependence.

Results and Discussions

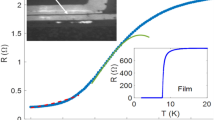

We begin to present our findings by showing the variation of R with T, measured at B = 0. The respective R(T) plots, for 1 μm long wires with 3 different w, 24, 48, 100 nm, are shown in Fig. 1. The co-fabricated reference film has also been measured and the zero field R(T) for it is shown in the inset of Fig. 1 for comparison. It is seen that all the wires exhibited exponential (linear in semi-log scale) drop, signifying superconducting transition at B = 0. Nonetheless, they saturated at non-zero values and a residual R persist at low- T. The approach of 1D regime is herald by the higher value of the transition width (Δ(T)) in wires (ΔTwire ≈ 2 K) than that of the film (ΔTFilm ≈ 1.10 K)20,34.

The T variation of R (in semi-log scale) at B = 0 for 1 μm long wires with different [24(blue), 48(green) and 100(red) nm] widths.

The wires show superconducting transition at TC around 1.8 K. Below TC, at lowest T, R saturate at finite values. (Inset:) R-T for the simultaneously prepared film, measured at B = 0 shows a sharp drop at TC = 1.76 K and R appeared to go to zero.

The presence of residual R in the wires, far below TC, and broadening of R(T) might be related to the phase slip process due to quantum fluctuations. There can obviously be other source of R(T) broadening that one can consider. The widening could result from the fact that a too high current has been used during the measurements. To rule out this possibility, we acquired R(T) curves for small current value (see Methods). It is also recognized that inhomogeneities may give rise to broad transition21,35. Although our system, a:InO is disordered by default, the film showed a sudden drop at TC signifies that this thickness of evaporated a:InO leads to continuous films and the morphology is not granular25.

A more convincing and plausible way to explain the R(T) broadening and non-zero R at lowest T, is the excitation of phase slips. When the activation of phase slips is thermally driven, the formula for R is obtained from a model, originally described by Langer–Ambegaokar–McCumber–Halperin (LAMH). Within this model, phase slip formation necessitates overcoming an energy barrier (ΔF). A characteristic timescale for the fluctuations is fixed by a pre-factor Ω, related to the attempt frequency of random excursions in the superconducting order parameter. The resultant fluctuation-dominated resistance of a 1D superconducting wire can be expressed as follows

where,  is the attempt frequency,

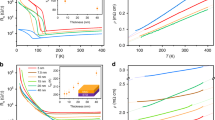

is the attempt frequency,  is the Ginzburg-Landau characteristic relaxation time and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The experimental data with the LAMH fitting in dashed line is shown in Fig. 2. This model can only describe the experimental data near TC and clearly fails as T is lowered. It is worth noting here that the peak as obtained from eq. 1, has no physical meaning and is a mathematical artifact16.

is the Ginzburg-Landau characteristic relaxation time and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The experimental data with the LAMH fitting in dashed line is shown in Fig. 2. This model can only describe the experimental data near TC and clearly fails as T is lowered. It is worth noting here that the peak as obtained from eq. 1, has no physical meaning and is a mathematical artifact16.

RvsT for the 3 wires of different widths as in Fig. 1.

The dashed lines are the fitting of the experimental data with TAPS model, whereas the solid lines are the fitting with the simplified short wire model.

The failure of TAPS model at lower Ts, allowed us to consider QPS phenomenon to be present at that side of the data. Because of the high normal state resistance in our sample it is advantageous for us to use QPS23. Following the simplified short wire model36,37, the QPS contribution to the effective resistance of a superconducting wire with length L and cross section σ can be written as,

where Δ(T) and ξ(T) are temperature dependent superconducting energy gap and coherence length, respectively.  is the QPS action and RQ = h/4e2 is the quantum resistance of Cooper pairs, where h is Plank’s constant and e is the electronic charge. The fitting to this form, using A and (L/ξ) as parameter, has also been shown in Fig. 2 as solid lines. The onset temperature and the normal-state resistance can be obtained from experimental RT dependences. For all wires the best fitted values of A is in the range of 0.13 to 0.16. We found that the correspondence between the simplified short-wire model37 and the experiment can be considered as good.

is the QPS action and RQ = h/4e2 is the quantum resistance of Cooper pairs, where h is Plank’s constant and e is the electronic charge. The fitting to this form, using A and (L/ξ) as parameter, has also been shown in Fig. 2 as solid lines. The onset temperature and the normal-state resistance can be obtained from experimental RT dependences. For all wires the best fitted values of A is in the range of 0.13 to 0.16. We found that the correspondence between the simplified short-wire model37 and the experiment can be considered as good.

We also explore that at certain limits, this renormalization model37 predicts a functional dependence of the effective R on T. In the high-temperature limit, R ~ T 2γ−2, where  is the dimensionless conductance related to the effective quasiparticle resistance Rqp, and associated with dissipation provided by the quasiparticle channel21. The results of fitting on our R(T) data with this form has been shown in Fig. 3. The value of Rqp came out from the fitting is 2.5 kΩ, which is significantly smaller than RN.

is the dimensionless conductance related to the effective quasiparticle resistance Rqp, and associated with dissipation provided by the quasiparticle channel21. The results of fitting on our R(T) data with this form has been shown in Fig. 3. The value of Rqp came out from the fitting is 2.5 kΩ, which is significantly smaller than RN.

Resistance vs temperature for three samples of the same length but different width as in Fig. 2.

Black solid lines are fittings to power dependence R ~ T 2γ−2.

The saturation in R at the low- T is not understood, but it might be due to isolated barriers such as microcracks and twin boundaries separating macroscopic phase-coherent superconducting regions16. It is interesting to note that Rsat increases as decrease in wire width, although at normal state (T = 4 K), all of them had almost same R. This might indicate the increase of phase slip centers as the width of wires decreases.

For the rest, we will focus on the B dependence of R of the devices. We begin the presentation of our B-dependent data by plotting, in Fig. 4(a), the R(B) isotherms (in semi-log scale) obtained for the film, over our entire B range. The isotherms crossed each other at a particular B, (Bc ≅ 4.05 T), signifying SIT. At Bc, the sheet R (R□) is equal to 6.5 kΩ which is close to R [=6.47 kΩ], and is in accordance with the bosonic description of SIT38. The high- B phenomenology exhibited by this film was similar to our previously studied a:InO films25,39,40,41,42. In Fig. 4(b) the R vs B isotherms for the 48 nm wide wire is shown. Although B is expected to increase R, we find, near zero B, the residual R was actually suppressed by the application of B, leading to nMR over a certain B range. After that, R increased with B. The B-driven SIT occurs as the isotherms crossed at 10 T. It is interesting to see that, although at zero B the wire has a higher R than the film, its R changed much slowly with B in comparison and did not reach to as high R as the film at low- T25. The appearance of low- B nMR in sub-100 nm wide wires is the main focus here.

(a) The R vs B isotherms (in semi-log scale) for the film, showing B-driven SIT (Bc ≈ 4.05 T). At Bc, R is 6.5 kΩ, which is close to quantum resistance of Cooper pair. (b) The R(B) isotherms for w = 48 nm wire at the same Ts as of the film (see the color palette). The low-field magnetoresistance peak at B = 0 is clearly visible. The isotherms cross each other at B = 10 T, signifying SIT.

In order to establish that the observed nMR appeared in wires of width less than or equal to 100 nm, irrespective of length, we show in Fig. 5 the R vs B isotherms for 200 and 100 nm wide and 10 μm long wire. The left axis shows the R value for the 200 nm wide wire, whereas, the right axis is for the 100 nm wide wire. Negative magnetoresistance near B = 0 is observed in 100 nm wire whereas it is absent in 200 nm wire. For 1 μm long wire with 100 nm width, pronounced nMR was also observed and will be discussed later.

We believe that the nMR is a genuine effect and not an artifact of the contacts, if it was so, the wider wires along with the film would also show this behavior. In order to get more insight of this effect, we studied its detail T and w dependence for L = 1 μm long wires.

In Fig. 6(a–c), the variation of change in R with B near zero- B, measured at 3 different Ts, viz; 0.05, 0.70 and 1.10 K for w = 24, 48 and 100 nm wires are shown. For the ease of comparison, we prefer to present our data in a normalized scale, where R(0) is the zero B resistance and ΔR = [R − R(0)] is the change in R from the zero B value. The wire resistance decreased by 20–30% from their respective zero- B values, before R started to increase. It can be seen from Fig. 6(d) that magnitude of nMR increased with T up to 1.10 K in all the wires. The TC of the wires are around 1.8 K, and unfortunately we were unable to measure the MR very close to TC, where this nMR might disappear. The change in magnitude of nMR with T is more prominent in the wider wires whereas for the narrowest of them (w = 24 nm) it is fairly constant around 20%.

The variation of change in R with B measured at 3 different Ts; 0.05 K (blue), 0.70 K (green) and 1.10 K (red) for w = (a) 24 nm (b) 48 nm and (c) 100 nm wire. The data are normalized with respect to zero B resistance [R(0)]. ΔR = [R − R(0)] is the change in R from R(0). The lines joining the data points are to guide the eye. (d) The variation of percentage change of MR  with T for wires of w = 24 nm (blue), 48 nm (green) and 100 nm (red). The lines are to guide the eye.

with T for wires of w = 24 nm (blue), 48 nm (green) and 100 nm (red). The lines are to guide the eye.

To look at the effect of wire width on the nMR, we plot in Fig. 7(a–c) the nMR measured for 3 different widths; 24, 48 and 100 nm at 0.05 K, 0.70 K and 1.0 K respectively. At low- T the narrower wire has more change than the wider wires, whereas the scenario changes as T is increased. It is also seen that at low- T, all the wires have, almost same broadening and as T was increased, the wider wires changed more sharply than the narrower one. In order to represent this observation quantitatively, we followed a prescription described hereinafter. Since near B = 0, R changes linearly with B, we calculate the slope to measure how fast R changed with B. The T variation of this slope (q) for wires with different w is shown in Fig. 7(d). The slope for all the wires stayed fairly constant up to 0.5 K and changed above that. The magnitude of nMR for different wires [Fig. 6(d)] crossed around the same T. The crossover field, the magnetic field after which the positive MR took over, was decreased with increase in T for all the wires, which also came out of this analysis independently. This also suggests that although up to 0.5 K, the crossover field does not depend on size, but it decreased with the increase in wire width above that.

The variation of change in R with B measured for 3 different w; 24 (blue), 48 (green) and 100 nm (red) at T = (a) 0.05 K (b) 0.70 K and (c) 1.0 K. The data are normalized with respect to zero B resistance [R(0)]. ΔR = [R − R(0)] is the change in R from R(0). The lines joining the data points are to guide the eye. (d) The variation of the slope (q) (see text) with T suggests that in the nMR regime the rate of change of R with B increases as T is increased. For wires of different w, q stays fairly constant up to 0.5 K. The lines are to guide the eye.

It is inferred from Figs 6 and 7 that T and wire’s w have a close correlation in the evolution of this low- B nMR in ultra-narrow wires.

One of the plausible explanations of this nMR is related to presence of magnetic impurities and subsequent Kondo mechanism. We rule out this possibility based on couple of features. First, a:InO was evaporated with ultra-pure In2O3 pellets, in an HV chamber, where magnetic materials have never been processed. Second, there is a pronounced diameter dependence, as discussed earlier, making nMR observable only in sub-100 nm wide nanowires. Since the presence of magnetic impurities is not obvious, the model43 for the enhancement of critical current under B as observed in MoGe and Nb nanowires44 do not hold here, where deliberate magnetic impurities were introduced to get nMR.

Though nMR has also been predicted in disordered superconducting wires45, the contribution responsible for nMR within this model is exponentially small, which is not the case in our experiment. It can also be thought of that the low- B nMR is due to the suppression of weak localization46,47 by magnetic field. But a closer look at our nMR results reveals some facts which are contradictory to the weak localization proposition48. First, the change in R within the weak localization picture is only 2–3%46,47,48, whereas we observed more than 20% change of nMR over the B range. Second, the T variation of the phase coherence length, Lϕ. It is determined from the broadening (ΔB) of nMR peak width around B = 0. It is expected within weak localization model, that ΔB will increase with T, leading a decrease in Lϕ48. We observe, on the other hand, the peak gets sharper (see Figs 6 or 7(d)) as T is increased. Because of the above stated features, weak localization correction to the conduction failed to explain our results, suggesting some other mechanism being operated here.

Another explanation of this nMR at low B in sub 100 nm wide wires might be related to suppression of the non-equilibrium charge imbalance process at normal-superconducting (N-S) boundaries, as previously observed in Sn stripes49 and narrow Al loops50. In narrower samples, due to high current density phase-slip centers created and works as N-S boundaries. At N-S interface the superconducting energy gap Δ(T) retrieve itself fully over the coherence length ξ(T) of the superconductor. In presence of an external bias current for  , the excitations from N propagate into S result a quasi-particle current in the superconductor. The length scale of the quasi particle current is known as charge-imbalance relaxation length, λQ. This gives rise to finite boundary resistance corresponding to length λQ, for each such boundary. In presence of B, λQ decreases with increase in B, hence, the corresponding boundary resistance also decreased, lead to nMR in the system. The observation of nMR in sub 100 nm wide wires showed that suppression of non-equilibrium charge-imbalance processes by B, might play a key role in electronic transport below TC, and on the contrary its effect on wider wires and the 2D film is negligible. Although the dimensions of tin micro bridges49 is significantly larger than our wires, the Al loops50 are of the same dimensions. But these results were obtained and explained with charge imbalance theory at much higher T (≥0.3 K) than ours (50 mK). The TC for Al is 1 K whereas in our case it is 1.8 K. Initially, the validity of charge imbalance mechanism is questionable for T ≪ Tc, but later, of late, a low temperature limit for the charge imbalance process was proposed51 and experimentally observed52.

, the excitations from N propagate into S result a quasi-particle current in the superconductor. The length scale of the quasi particle current is known as charge-imbalance relaxation length, λQ. This gives rise to finite boundary resistance corresponding to length λQ, for each such boundary. In presence of B, λQ decreases with increase in B, hence, the corresponding boundary resistance also decreased, lead to nMR in the system. The observation of nMR in sub 100 nm wide wires showed that suppression of non-equilibrium charge-imbalance processes by B, might play a key role in electronic transport below TC, and on the contrary its effect on wider wires and the 2D film is negligible. Although the dimensions of tin micro bridges49 is significantly larger than our wires, the Al loops50 are of the same dimensions. But these results were obtained and explained with charge imbalance theory at much higher T (≥0.3 K) than ours (50 mK). The TC for Al is 1 K whereas in our case it is 1.8 K. Initially, the validity of charge imbalance mechanism is questionable for T ≪ Tc, but later, of late, a low temperature limit for the charge imbalance process was proposed51 and experimentally observed52.

Although the phenomena of nMR is not totally understood yet, but it might be related to reduction or suppression of phase slip barrier (Δ0) or rate of activated phase slips as a aftermath of suppression of the charge imbalance length with B. In the beginning, it appears contradictory, since the reduction of Δ0 will prompt the increase in R. It was argued in ref. 36 that at low- T, reduction of Δ0 may lead to an increase in number of quasi-particles, which in turn reduce R. Hence, the observed MR is related to the interplay between these two B dependent contributions. It is quite feasible indeed, that over a certain region of parameter, the second mechanism wins over the first and R decreases with increasing B. At high B, Δ0 is suppressed and R increased with B as expected. However, it is very difficult to make any quantitative comparison with our experiments from this qualitative argument and a strong theoretical modeling is still required.

Summary and Conclusions

We perform magneto transport measurements at low- T environment in quasi- 1D structures of a:InO. The nanowires were fabricated by e-beam lithography, followed by e-gun evaporation of high purity In2O3. The T-dependence of R was explained in terms of available phase slip models. Nanowires of width equal to or less than 100 nm, irrespective of length, show nMR near zero B. This nMR was found to depend closely on both T and width of the nanowire. This phenomena was qualitatively attributed due to an interplay between two field dependent contributions.

Methods

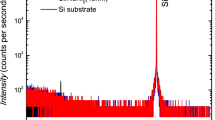

Our data were obtained from studies of several nanowires of different widths (w) and lengths (L), but, we will mainly focus on the results for L = 1 μm long wires of 3 different w. These were initially defined by e-beam lithography on a Si/SiO2 wafer. a:InO was deposited by e-gun evaporation of ultra-pure (99.999%) In2O3 pellets in an O2 atmosphere ( = 1.05e-5 Torr). The thickness of deposition was 25 nm as measured in-situ by a quartz crystal monitor. Since a:InO has been extensively used to investigate superconductor to insulator transition (SIT) in 2D39,40,41,53,54, we simultaneously prepared one reference film of size 50 × 165 μm, for comparative study. The electrically continuous a:InO films of this thickness are not granular in morphology. The gold contacts were patterned via optical lithography, followed by metal evaporation and lift off. The zero field measurements were performed in a He-3 cryostat and the magnetoresistance data were obtained by cooling the devices in a dilution refrigerator. To ensure the reliability of measurements, the cryostat with well filtered coax lines were used. Experiment lines were twisted and fed through low-pass filters to eliminate the effect of external EM noise on measurements. The transport measurements were conducted in a two-terminal configuration by low frequency (7.147 Hz) ac lock-in techniques under current biased condition. The signal from the sample was amplified by a homemade differential preamplifier prior to be detected in lock-in amplifiers. The lock-in frequency was also chosen such that none of its higher order harmonics matches with the line frequency. All the instruments and the refrigerators were connected properly to a single ground to ensure that there exists no ground loop(s). While measuring in current biased condition, a standard requirement is to keep the bias current much smaller than the critical current to avoid hysteresis effects due to overheating. Additionally, in order to stay within the linear response regime, the measuring current should remain smaller than the characteristic scale I0 = kBTC/ϕ0 equal to few tens of nA for the majority of materials33. We used 1 nA biasing current in all our measurements. The details of fabrication and measurements can be found in ref. 25. Contact R was subtracted prior to any comparison.

= 1.05e-5 Torr). The thickness of deposition was 25 nm as measured in-situ by a quartz crystal monitor. Since a:InO has been extensively used to investigate superconductor to insulator transition (SIT) in 2D39,40,41,53,54, we simultaneously prepared one reference film of size 50 × 165 μm, for comparative study. The electrically continuous a:InO films of this thickness are not granular in morphology. The gold contacts were patterned via optical lithography, followed by metal evaporation and lift off. The zero field measurements were performed in a He-3 cryostat and the magnetoresistance data were obtained by cooling the devices in a dilution refrigerator. To ensure the reliability of measurements, the cryostat with well filtered coax lines were used. Experiment lines were twisted and fed through low-pass filters to eliminate the effect of external EM noise on measurements. The transport measurements were conducted in a two-terminal configuration by low frequency (7.147 Hz) ac lock-in techniques under current biased condition. The signal from the sample was amplified by a homemade differential preamplifier prior to be detected in lock-in amplifiers. The lock-in frequency was also chosen such that none of its higher order harmonics matches with the line frequency. All the instruments and the refrigerators were connected properly to a single ground to ensure that there exists no ground loop(s). While measuring in current biased condition, a standard requirement is to keep the bias current much smaller than the critical current to avoid hysteresis effects due to overheating. Additionally, in order to stay within the linear response regime, the measuring current should remain smaller than the characteristic scale I0 = kBTC/ϕ0 equal to few tens of nA for the majority of materials33. We used 1 nA biasing current in all our measurements. The details of fabrication and measurements can be found in ref. 25. Contact R was subtracted prior to any comparison.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mitra, S. et al. Negative Magnetoresistance in Amorphous Indium Oxide Wires. Sci. Rep. 6, 37687; doi: 10.1038/srep37687 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Zhang, L.-F., Covaci, L., Milošević, M. V., Berdiyorov, G. R. & Peeters, F. M. Unconventional vortex states in nanoscale superconductors due to shape-induced resonances in the inhomogeneous cooper-pair condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett 109, 107001 (2012).

Arutyunov, K. Negative magnetoresistance of ultra-narrow superconducting nanowires in the resistive state. Physica C: Superconductivity 468, 272 (2008).

Mooij, J. E. et al. Superconductor–insulator transition in nanowires and nanowire arrays. New Journal of Physics 17, 033006 (2015).

Petrovic, A. P. et al. Individual topological tunnelling events of a quantum field probed through their macroscopic consequences. Nat. Communications 7, 12262 (2016).

Little, W. A. Decay of persistent currents in small superconductors. Phys. Rev. 156, 396 (1967).

Newbower, R. S., Beasley, M. R. & Tinkham, M. Fluctuation effects on the superconducting transition of tin whisker crystals. Phys. Rev. B 5, 864 (1972).

Langer, J. S. & Ambegaokar, V. Intrinsic resistive transition in narrow superconducting channels. Phys. Rev. 164, 498 (1967).

McCumber, D. E. & Halperin, B. I. Time scale of intrinsic resistive fluctuations in thin superconducting wires. Phys. Rev. B 1, 1054 (1970).

Giordano, N. Evidence for macroscopic quantum tunneling in one-dimensional superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett 61, 2137 (1988).

Giodano, N. Superconducting fluctuations in one dimension. Physica B: Condensed Matter 203, 460–466 (1994).

Yu Chen & Yen-Hsiang Lin & Stephen D. Snyder & Allen M. Goldman & Alex Kamenev . Dissipative superconducting state of non-equilibrium nanowires. Nat. Phys 10, 567 (2014).

Sahu, M. et al. Individual topological tunnelling events of a quantum field probed through their macroscopic consequences. Nat. Phys. 5, 503 (2009).

Shah, N., Pekker, D. & Goldbart, P. M. Inherent stochasticity of superconductor-resistor switching behavior in nanowires. Phys. Rev. Lett 101, 207001 (2008).

Li, P. et al. Switching currents limited by single phase slips in one-dimensional superconducting al nanowires. Phys. Rev. Lett 107, 137004 (2011).

Singh, M. & Chan, M. H. W. Observation of individual macroscopic quantum tunneling events in superconducting nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 88, 064511 (2013).

Ansermet, D. et al. Reentrant phase coherence in superconducting nanowire composites. ACS Nano 10, 515 (2016).

Baumans, Xavier D. A. et al. Thermal and quantum depletion of superconductivity in narrow junctions created by controlled electromigration. Nat. Communications 7, 10560 (2016).

Arutyunov, K. Y., Hongisto, T. T., Lehtinen, J. S., Leino, L. I. & Vasiliev, A. L. Quantum phase slip phenomenon in ultra-narrow superconducting nanorings. Scientific Reports 2, 293 (2012).

Garanin, D. A. & Chudnovsky, E. M. Quantum decay of the persistent current in a josephson junction ring. Phys. Rev. B 93, 094506 (2016).

Sharifi, F., Herzog, A. V. & Dynes, R. C. Crossover from two to one dimension in in situ grown wires of pb. Phys. Rev. Lett 71, 428 (1993).

Zgirski, M., Riikonen, K.-P., Touboltsev, V. & Arutyunov, K. Y. Quantum fluctuations in ultranarrow superconducting aluminum nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 77, 054508 (2008).

Johansson, A., Sambandamurthy, G., Shahar, D., Jacobson, N. & Tenne, R. Nanowire acting as a superconducting quantum interference device. Phys. Rev. Lett 95, 116805 (2005).

Lehtinen, J. S., Sajavaara, T., Arutyunov, K. Y., Presnjakov, M. Y. & Vasiliev, A. L. Evidence of quantum phase slip effect in titanium nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 85, 094508 (2012).

Lau, C. N., Markovic, N., Bockrath, M., Bezryadin, A. & Tinkham, M. Quantum phase slips in superconducting nanowires. Phys. Rev. Lett 87, 217003 (2001).

Mitra, S., Tewari, G. C., Mahalu, D. & Shahar, D. Finite-size effects in amorphous indium oxide. Phys. Rev. B 93, 155408 (2016).

Graybeal, J. M., Mankiewich, P. M., Dynes, R. C. & Beasley, M. R. Apparent destruction of superconductivity in the disordered one-dimensional limit. Phys. Rev. Lett 59, 2697 (1987).

Kim, H., Jamali, S. & Rogachev, A. Superconductor-insulator transition in long moge nanowires. Phys. Rev. Lett 109, 027002 (2012).

Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity (McGraw Hill), second edn, (1996).

Xiong, P., Herzog, A. V. & Dynes, R. C. Negative magnetoresistance in homogeneous amorphous superconducting pb wires. Phys. Rev. Lett 78, 927 (1997).

Fu, H. C., Seidel, A., Clarke, J. & Lee, D.-H. Stabilizing superconductivity in nanowires by coupling to dissipative environments. Phys. Rev. Lett 96, 157005 (2006).

Kivelson, S. A. & Spivak, B. Z. Aharonov-bohm oscillations with period hc /4 e and negative magnetoresistance in dirty superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 45, 10490 (1992).

Kharitonov, M. Y. & Feigelman, M. V. Enhancement of superconductivity in disordered films by parallel magnetic field. JTEP Lett. 82, 421 (2005).

Arutyunov, K., Golubev, D. & Zaikin, A. Superconductivity in one dimension. Phys. Rep. 464, 1 (2008).

Giordano, N. Dissipation in a one-dimensional superconductor: Evidence for macroscopic quantum tunneling. Phys. Rev. B 41, 6350 (1990).

Zgirski, M. & Arutyunov, K. Y. Experimental limits of the observation of thermally activated phase-slip mechanism in superconducting nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 75, 172509 (2007).

Zaikin, A. D., Golubev, D. S., van Otterlo, A. & Zimanyi, G. T. Quantum fluctuations and dissipation in thin superconducting wires. Physics-Uspekhi 41, 226 (1998).

Zaikin, A. D., Golubev, D. S., van Otterlo, A. & Zimányi, G. T. Quantum phase slips and transport in ultrathin superconducting wires. Phys. Rev. Lett 78, 1552 (1997).

Fisher, M. P. A. Quantum phase transitions in disordered two-dimensional superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett 65, 923 (1990).

Sambandamurthy, G., Engel, L. W., Johansson, A. & Shahar, D. Superconductivity-related insulating behavior. Phys. Rev. Lett 92, 107005 (2004).

Sambandamurthy, G., Engel, L. W., Johansson, A., Peled, E. & Shahar, D. Experimental evidence for a collective insulating state in two-dimensional superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett 94, 017003 (2005).

Ovadia, M., Kalok, D., Sacepe, B. & Shahar, D. Duality symmetry and its breakdown in the vicinity of the superconductor-insulator transition. Nat Phys. 9, 415 (2013).

Shammass, I., Cohen, O., Ovadia, M., Gutman, I. & Shahar, D. Superconducting correlations in thin films of amorphous indium oxide on the insulating side of the disorder-tuned superconductor-insulator transition. Phys. Rev. B (R) 85, 140507 (2012).

Wei, T.-C., Pekker, D., Rogachev, A., Bezryadin, A. & Goldbart, P. M. Enhancing superconductivity: Magnetic impurities and their quenching by magnetic fields. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 75, 943 (2006).

Rogachev, A. et al. Magnetic-field enhancement of superconductivity in ultranarrow wires. Phys. Rev. Lett 97, 137001 (2006).

Pesin, D. A. & Andreev, A. V. Suppression of superconductivity in disordered interacting wires. Phys. Rev. Lett 97, 117001 (2006).

Bergmann, G. Weak localization in thin films: a time-of-flight experiment with conduction electrons. Physics Reports 107, 1 (1984).

Altshuler, B. L., Aronov, A. G. & Khmelnitsky, D. E. Effects of electron-electron collisions with small energy transfers on quantum localisation. Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics 15, 7367 (1982).

Chiquito, A. J., Lanfredi, A. J. C., de Oliveira, R. F. M., Pozzi, L. P. & Leite, E. R. Electron dephasing and weak localization in sn doped in2o3 nanowires. Nano Letters 7, 1439 (2007).

Kadin, A., Skocpol, W. & Tinkham, M. Magnetic field dependence of relaxation times in nonequilibrium superconductors. Journal of Low Temperature Physics 33, 481 (1978).

Santhanam, P., Umbach, C. P. & Chi, C. C. Negative magnetoresistance in small superconducting loops and wires. Phys. Rev. B 40, 11392 (1989).

Hübler, F., Lemyre, J. C., Beckmann, D. & v. Löhneysen, H. Charge imbalance in superconductors in the low-temperature limit. Phys. Rev. B 81, 184524 (2010).

Arutyunov, K. Y., Auraneva, H.-P. & Vasenko, A. S. Spatially resolved measurement of nonequilibrium quasiparticle relaxation in superconducting al. Phys. Rev. B 83, 104509 (2011).

Ovadia, M. et al. Evidence for a finite-temperature insulator. Sci. Rep. 5, 13503 (2015).

Doron, A. et al. Nonequilibrium second-order phase transition in a cooper-pair insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett 116, 057001 (2016).

Acknowledgements

S.M. and G.C.T. thank Karen Michaeli, Sumilan Banerjee and Arjun Joshua for fruitful discussions and department’s submicron center for providing necessary support in device fabrication. S.M. thanks VATAT program for post-doctoral fellowship support. This work was supported by the Minerva Foundation with funding from Federal German Ministry for Education and Research, and by a grant from the Israel Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S. conceived the experiment, S.M. and D.M. design the devices in e-beam lithography, S.M. fabricated the samples, S.M. and G.C.T. conducted the experiments in dilution refrigerator, S.M., G.C.T. and D.S. analyzed the results and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mitra, S., Tewari, G., Mahalu, D. et al. Negative Magnetoresistance in Amorphous Indium Oxide Wires. Sci Rep 6, 37687 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37687

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37687

This article is cited by

-

Granularity mediated multiple reentrances with negative magnetoresistance in disordered TiN thin films

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Quantum phase transition from superconducting to insulating-like state in a pressurized cuprate superconductor

Nature Physics (2022)

-

Current dependence of the negative magnetoresistance in superconducting NbN nanowires

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Survival of Topological Surface States in Cobalt Doped Sb2Te3

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.