Abstract

One-pot hydrothermal synthesis of MoS2 nanoplatelet arrays on various substrates is perhaps the most promising approach to fabricate efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. However, the main challenges in this synthesis remain the purity and crystallinity of MoS2. In this study, we show for the first time that irradiation of amorphous, defect-rich MoS2 nanoplatelets with a green nanosecond laser at a proper irradiation dose, ca ≤0.35 J cm−2, can significantly improve the crystallinity and purity of MoS2 nanoplatelets. The effect was confirmed by Raman spectroscopy investigations demonstrating a surprising intensity increase of the A1g and  modes after the laser irradiation. Further increase of irradiation energy, however, resulted in the photocorrosion and destruction of MoS2 nanoplatelets. The variation of A1g and

modes after the laser irradiation. Further increase of irradiation energy, however, resulted in the photocorrosion and destruction of MoS2 nanoplatelets. The variation of A1g and  Raman mode intensities ratio depending on the green light irradiation dose was also presented and is discussed below.

Raman mode intensities ratio depending on the green light irradiation dose was also presented and is discussed below.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single and few-layered dichalcogenides of transition metal, such as MoS2, MoSe2, TiSe2, WS2, NbS2, recently are among research topics due versatile their properties. Compared with other dichalcogenides, 2D MoS2 architectures have attracted more attention and have been intensively investigated over the past several years. The increased interest in this semiconducting material is due to graphitic-type morphology with exciting electronic1,2, optical3,4,5 and catalytical6,7 properties. Besides, few-layered MoSx lamellar structures in the form of crystalline7,8,9 or amorphous10,11 states are attributed to prospective electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) from acidic solutions. However, 2D MoS2 has poor conductivity owing to semi-conductive nature and hence, poor HER efficiency. During the past few years, several methods have been reported on the formation of low charge-transfer resistant hybride12,13 and 2D defect-rich9 MoS2 materials. For example, the oxygen-incorporated MoS2, possessing a narrower band gap of 1.30 eV compared to that of the pristine 2H-MoS2 (1.75 eV) and better conductivity was proposed14. 2D MoO3 also showed excellent electrocatalytic activity for HER with the onset potential of −0.04 V vs. reference hydrogen electrode (RHE)15. It has been demonstrated that the defect-rich nanosheets possess additional exposure of active edge sites for HER generating more unsaturated sulphur atoms in the more disordered structure9. Besides that, inter-domain structure possesses a higher conductivity9.

The thickness of individual S-Mo-S layer in the pristine crystalline MoS2 was approximated to be equal to ≈0.63 nm16. In pristine crystals, the hexagonal 2H-type arrangement of atoms is more stable and dominant. As a result, rhombohedral 3R-type MoS2 phase transforms into 2H-type upon heating17. A pure 2 H phase can transform to a metastable metallic 1T phase upon Li-intercalation and exfoliation of S-Mo-S layers weakly interacting with each other by van der Walls forces18. In contrast to the 2 H structure, the MoS2 nanocrystals often exhibit a triangular morphology19. As reported, the triangular and hexagonal forms can be changed by varying the sulphiding and MoS2 formation conditions20. In the case of amorphous MoS2 materials, they usually have many defect sites and coordinately unsaturated S atoms21. As reported by Xie group9, the basal planes of MoS2 containing abundant defects can readily crack exposing additional active edge sites.

Except of mechanical and chemical exfoliation of pristine MoS2 crystals, nanocrystalline MoS2 can be synthesized by several methods including chemical vapour deposition22, thermal decomposition23, and hydrothermal/solvothermal treatment using different Mo and S- containing precursors24,25,26.

It is worth noticing, that MoSx-based single and few-layered materials possess a good visible light absorption27 and, in contrast to inert graphene, possesses versatile chemistry including various phase and compositional transformations upon annealing, storage, doping and photo-excitation. For example, it has been recently reported that edge sites of MoS2 monolayer are more resistant to photocatalytic degradation compared to few-layered MoS2 edges27. As a result, MoS2 was oxidized to MoOx in an aqua solution with photoexcited electrons.

In this study, we report for the first time the compositional and structural transformations of few-layered MoS2-based nanoplatelets induced by irradiation with the continuous wave (CW) or nanosecond-pulse lasers (ns) using the wavelength of 532 nm in air demonstrating that absorbed photons can induce drastic modifications towards the increase of purity and crystallinity of MoS2. These processes were studied as a function of the irradiation dose of monochromatic laser light in the ambient conditions as well as the initial purity of nanoplatelet arrays formed on the Ti substrate under adapted herein hydrothermal treatment conditions. X-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy were used to reveal the compositional and structural transformations of MoSx-based nanoplatelets.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and characterization by SEM and XRD

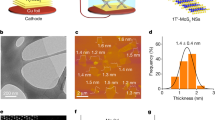

In this study, the synthesis of densely packed molybdenum sulphide nanoplatelet arrays on the Ti substrate was undertaken by one-pot hydrothermal synthesis way from ammonium heptamolybdate and thiourea solution under modified conditions, reported previously28. Briefly, 15 mL of 5 mmol L−1 (NH4)6Mo7O24 4H2O and 90 mmol L−1 thiourea solution were transformed in the Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, 25 mL in volume, and heated at 225 °C for 5 h or 15 h using 10 °C min−1 ramp, then cooled down naturally to the room temperature. Upon this procedure after 5 h autoclaving, the surface of Ti sample placed vertically in the autoclave solution was covered with a black- coloured nanoplatelet array with a quite uniform thickness of ≅400 nm (Fig. 1a). More detailed SEM and HRTEM investigations revealed the formation of quite uniformly sized and densely packed nanoplatelets with the thickness of 3–6 nm at their edge sites. An increase of the synthesis time up to 15 h resulted in the formation of a film composed of nanoplatelet and nano-flowered species with approximately twice smaller width of leaflets (Fig. 1b). Besides it, significantly thicker and uneven in thickness films usually were formed.

According to glancing angle XRD pattern, presented in Fig. 2, the crystallinity of MoS2 films fabricated on the Ti substrate in the adapted herein solution at 225 °C depended largely on the synthesis time. Figure 2 depicts the glancing angle XRD patterns taken from the films synthesized during 5 h (a) and 15 h (b). These specimens were labelled as S5 and S15, respectively. The array of nanoplatelets S5 possesses just low crystallinity since the observed clear diffraction peaks at 2θ = 35.18, 38.42, 40.18 and 53.08 deg, according to PDF card no 00-044-1294, should be ascribed to the Ti planes coming from the substrate. Increase in the synthesis time up to 15 h resulted in formation of the films excelling in good crystallinity and purity of MoS2 because all labelled diffraction peaks can be indexed to those of the pure rhombohedral phase of 3R-MoS2 with the lattice constants of a = 3.145, b = 3.145, c = 18.71 Å (Fig. 2b), which are consistent with the values of standard PDF card no. 04-004-4330.

(a) Glancing angle XRD patterns of the specimen S5 composed of nanoplatelet film fabricated on Ti substrate by hydrothermal synthesis in the solution containing 5 mmol L−1 (NH4)6Mo7O24 and 90 mmol L−1 thiourea at 225 °C for 5 h (a) before (1) and after (2) green light (λexc = 532 nm) irradiation with nanosecond laser beam of average irradiation dose of 12.74 J cm−2. In (b) the same XRD plot for as-grown specimen S15 without any laser irradiation.

Laser irradiation effects probed by Raman spectroscopy

In the next setup, the composition of nanoplatelets formed under conditions of this study was investigated by Raman spectroscopy. Raman spectroscopy is extremely sensitive to bonding strength and coordination symmetry; thus, different phases could be recognized from their distinct Raman spectra. The most studied 2H-MoS2 exhibits four first-order Raman bands located at 32 ( ), 286 (E1g), 383 (

), 286 (E1g), 383 ( ), and 408 cm−1 (A1g)29. The intensity of 286-cm−1 is very low, and usually two well-resolved bands near 383 and 408 cm−1 are used to recognize the 2H-MoS2 phase29,30. Note that A1g (408 cm−1) and

), and 408 cm−1 (A1g)29. The intensity of 286-cm−1 is very low, and usually two well-resolved bands near 383 and 408 cm−1 are used to recognize the 2H-MoS2 phase29,30. Note that A1g (408 cm−1) and  (383 cm−1) Raman modes are due to out-of-plane vibrations of only S atoms and opposite vibration of two S atoms with regard to Mo atom, respectively29,30,31. For a 1T-MoS2 structure, the theoretical analysis suggests the presence of two Raman active modes located at the lower frequencies, ca. 258.1 (Eg) and 356.5 cm−1 (A1g), differing from the corresponding modes of 2H phase31. Because of distorted structure the 1 T′-MoS2 polymorph, it is expected to observe many characteristic low frequency vibrational modes located at 139.2 (Ag), 146.3 (Bg), 209.0 (Bg), 216.3 (Ag), 317.9 (Ag), 336.0 (Ag), and 399.8 cm−1 (Ag)32. Considering the observed spectrum of the sample S5, taken after the green (532 nm) CW laser excitation with a low average power, namely 0.06 mW (2 kW cm−2), (Fig. 3a), the bands at 157 cm−1 and 313 cm−1 can be assigned to J1 and J3, modes of 1 T′-MoS2 structure, while the bands peaked near 351 and 414 cm−1 probably have some contribution from the 2H-MoS2 phase. Therefore, the Raman spectra of highly defected MoS2 specimen S5 demonstrate a low purity and amorphous structure of MoS2.

(383 cm−1) Raman modes are due to out-of-plane vibrations of only S atoms and opposite vibration of two S atoms with regard to Mo atom, respectively29,30,31. For a 1T-MoS2 structure, the theoretical analysis suggests the presence of two Raman active modes located at the lower frequencies, ca. 258.1 (Eg) and 356.5 cm−1 (A1g), differing from the corresponding modes of 2H phase31. Because of distorted structure the 1 T′-MoS2 polymorph, it is expected to observe many characteristic low frequency vibrational modes located at 139.2 (Ag), 146.3 (Bg), 209.0 (Bg), 216.3 (Ag), 317.9 (Ag), 336.0 (Ag), and 399.8 cm−1 (Ag)32. Considering the observed spectrum of the sample S5, taken after the green (532 nm) CW laser excitation with a low average power, namely 0.06 mW (2 kW cm−2), (Fig. 3a), the bands at 157 cm−1 and 313 cm−1 can be assigned to J1 and J3, modes of 1 T′-MoS2 structure, while the bands peaked near 351 and 414 cm−1 probably have some contribution from the 2H-MoS2 phase. Therefore, the Raman spectra of highly defected MoS2 specimen S5 demonstrate a low purity and amorphous structure of MoS2.

We found, however, that the green CW light excitation with larger power, ca 0.3 mW (10 kW cm−2), resulted in significant changes of the Raman response from the same sample (Fig. 3a) due to the formation of the 2H-MoS2 phase, clearly visible from the intense characteristic Raman bands peaked at 377 and 406 cm−1 29,30. The further increase in the green light excitation power up to 3.0 mW (100 kW cm−2), however, resulted in the photo-degradation of MoS2 viewed from the appearance of Raman bands peaked at 780, 826 and 846 cm−1 presumably due to formation of molybdenum oxides33,34,35. For comparison, the same effect was studied for pure MoS2 nanoplatelet/nanoflowered specimen S15 synthesized in the same solution via increase of the synthesis time up to 15 h (Fig. 3b). In this case, no changes in the MoS2 structure was observed for laser irradiation power up to 0.6 mW (20 kW cm−2); the presence of highly crystalline 2H-MoS2 structure was spectroscopically evident because of the appearance of intense characteristic bands at 382 ( ), and 408 cm−1 (A1g) in the Raman spectra. Thus, the observed Raman spectra of as-grown sample S15 evidence the presence of highly crystalline and pure MoS2. However, at higher excitation laser power, namely 3 mW (100 kW cm−2), drastic changes took place in the Raman spectrum evidencing the appearance of strong peaks at 819 and 993 cm−1, characteristic to molybdenum oxides33,34. The strong band ascribed to the Mo–O–Mo stretching vibration serves as a useful marker for discrimination of orthorhombic (820 cm−1) and monoclinic (848 cm−1) crystal phases. The clearly defined peaks at 127, 151, 285, 337, 662, 819, and 993 cm−1 evidence a laser-induced formation of orthorhombic MoO333,34,35. We hypothesized that observed laser-induced chemical transformation of MoS2 to α-MoO3 opens the possibility for simple laser writing on the MoS2 substrate creating the sites differing in their photo-resistance. At the same time, multiple peaks appear in a vicinity of 110 to 337 cm−1 instead of the typical 382 and 408 cm−1 bands of 2H-MoS2 implying on the photodecomposition of MoS2 and formation of non-stoichiometric molybdenum sulphides.

), and 408 cm−1 (A1g) in the Raman spectra. Thus, the observed Raman spectra of as-grown sample S15 evidence the presence of highly crystalline and pure MoS2. However, at higher excitation laser power, namely 3 mW (100 kW cm−2), drastic changes took place in the Raman spectrum evidencing the appearance of strong peaks at 819 and 993 cm−1, characteristic to molybdenum oxides33,34. The strong band ascribed to the Mo–O–Mo stretching vibration serves as a useful marker for discrimination of orthorhombic (820 cm−1) and monoclinic (848 cm−1) crystal phases. The clearly defined peaks at 127, 151, 285, 337, 662, 819, and 993 cm−1 evidence a laser-induced formation of orthorhombic MoO333,34,35. We hypothesized that observed laser-induced chemical transformation of MoS2 to α-MoO3 opens the possibility for simple laser writing on the MoS2 substrate creating the sites differing in their photo-resistance. At the same time, multiple peaks appear in a vicinity of 110 to 337 cm−1 instead of the typical 382 and 408 cm−1 bands of 2H-MoS2 implying on the photodecomposition of MoS2 and formation of non-stoichiometric molybdenum sulphides.

Processing of material it is easier to conduct by using pulsed laser systems. Therefore, more detailed analysis of the effect of laser processing parameters on the irradiation-induced transformation of MoS2 was performed by employing the nanosecond 532-nm laser setup. Before Raman spectroscopy analysis the S5 sample was treated by ns laser irradiation; the matrix of 1 × 1 mm2 areas with different laser irradiation dose were fabricated. Figure 4 shows that no changes in the spectrum of amorphous MoS2 took place until the irradiation dose reached 0.32 J cm−2. Further increase in the irradiation dose resulted in typical Raman spectrum of a highly crystalline MoS2 with two strong bands located at 408 and 377 cm−1; no bands characteristic to molybdenum oxides were detected even at the highest utilised irradiation dose (12.74 J cm−2). This might be associated with the different irradiation effect to the material in the case of CW and pulse laser. Intensity of CW laser is quite low (3 mW corresponds to 100 kW cm−2) and irradiation dose is proportional to irradiation time. We can expect photo-excitation and steady elevated temperatures of the specimen. In the case of pulse nanosecond laser, intensity is in the range of MW cm−2, however it affects the material for a short time (during the pulse) with relaxation between pulses. Therefore, photo-excited processes should dominate in this case. Oxidation is more related to permanent heating, and it is exhibited in Raman spectra (MoO3 bands) only after CW laser radiation. We could expect oxidation using ns-laser but with higher pulse energy or irradiation dose.

To determine quantitatively the laser irradiation dose required to induce transformation of amorphous structure to crystalline 2H-MoS2 phase, we have analyzed the dependence of relative intensity ratio of Raman bands I(313)/I(408) on the irradiation dose (Fig. 5). One can see that characteristic Raman feature of the amorphous phase is located near 313 cm−1, while the crystalline structure shows the intense band at 408 cm−1 (Fig. 3). Thus, a decrease in the intensity ratio I(313)/I(408) manifests transformation of amorphous to the crystalline phase. Experimental data were fitted by a sigmoidal form curve assuming a two-state mechanism forthe changes in Raman spectra. The transition point of the irradiation dose was found to be equal to 0.35 ± 0.007 J/cm2.

Laser irradiation effects probed by XRD

XRD studies revealed (Fig. 2a (curve 2)) that illumination of nanoplatelet specimen S5 with the 532 nm nanosecond laser beam of the average irradiation dose 12.7 J cm−2 resulted in an increase of MoS2 crystallinity evident from the new diffraction peaks observed at 2θ = 14.40, 35.78, 39.60 and 44.16 deg (Fig. 2a). Besides that, several shoulders peaked at 2θ = 34.14, 44.68 and 59.26 deg, according to the PDF card no 01-089-5566, belongs to the formation of non-stoichiometric molybdenum sulphide Mo1.18Mo6S2.

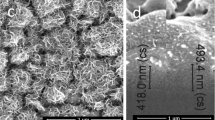

SEM observations of irradiated zones

Figure 6 depicts the top-side SEM images of nanoplatelet MoS2-based specimen S5 before and after the green nanosecond laser irradiation with the doses of 8.92 and 12.74 J cm−2. As seen, in the case of irradiation with the 8.92 J cm−2 dose, the design of nanoplatelets array remained the same. In the case of the 12.74 J cm−2 irradiation dose, obvious changes are observed. In this case, the distortion of nice nanoplatelets carpet becomes evident, although, some part of nanoplatelets edges are still visible.

Top-side SEM view of nonstoichiometric MoS2 nanoplatelets formed at the Ti substrate as in Fig. 1a, before (a) and after (b,c) 532 nm nanosecond laser treatment with 8.92 (b) and 12.74 J cm−2 (c) irradiation dose.

XPS Investigations of irradiated zones

To determine the state and elemental composition of nanoplatelet film on the surface before and after the green light irradiation, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy investigations were further performed. In the case of the as-grown sample S5, the XPS survey spectrum showed the presence of the Mo, S, O and C elements. The carbon peak was mainly ascribed to the adventitious hydrocarbon from the XPS spectrometer itself and was not further analysed. The high-resolution XPS spectra of Mo 3d and S 2p core level regions are shown in Fig. 7. In the case of Mo 3d spectrum of as-grown sample S5 (Fig. 7a), it can be well deconvoluted with three doublets identified according to NIST XPS database36 as MoS2 (Mo3d5/2 BE = 228.64 eV and 3d3/2 BE = 231.69 eV), MoO2 (Mo3d5/2 BE = 229.80 eV) and MoO3 (Mo3d5/2 BE = 232.94 eV). The S 2p core level XPS spectrum of the same S5 sample is fitted by three BE components peaked mainly at 161.49 eV and 162.70 eV attributable to S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 binding energies of the sulphur in MoS2. The third component with a BE = 163.89 eV and FWHM of 1.14 eV according to36 should be ascribed to the elemental sulphur inclusions. Judging from the BE peaks area ratio, the composition of as-grown S5 specimen nanoplatelets at the surface side should comprise of 53.20% MoS2, 15.5% MoO3, 23.7% MoO2 and 7.6% S0, indicating the dominant amount of MoS2.

The irradiation of the same S5 sample with the with 532 nm nanosecond laser with 8.92 J cm−2 irradiation dose resulted in obvious changes of the Mo 3d (Fig. 7c) and S 2p (Fig. 7d) core level spectra counterparts. First of all, the content of MoO2, MoO3 and S0 inclusions decreased down to 12.2%, 6.15% and 3.9%, whereas the content of MoS2 increased up to 77.7% correlating well with the Raman spectra changes. Secondly, from the deconvolution of the S 2p core level spectrum of the irradiated S5 specimen (Fig. 7d) two additional BE peaks, in addition to those attributable to MoS2 (BE = 161.96 eV and BE = 163.96 eV) and S0 (BE = 164.54 eV) (FWHM 0.90 eV) and BE = 168.84 eV (FWHM 1.07 eV) appeared which, according to36,37, should be ascribed to the formation of Mo(VI) sulphides and SO4−2 group, respectively.

Conclusions

This work reported the extraordinary effect induced by the green (532 nm) CW and ns-laser light induced of the compositional and phase transformations of 2D MoSx-based nanoplatelets containing some amount of MoO2 and MoO3 and elemental sulphur towards significantly more crystalline and pure MoS2 without obvious morphological changes. Consequently, this study established a novel method to increase the purity of MoS2 nanoplatelet arrays formed by the one-pot hydrothermal synthesis approach without additional annealing and sulphidation procedures. The effect was seen for visible green (λexc = 532 nm) laser light irradiation when the suitable irradiation dose was applied. An apparent decrease in the intensity ratio of I(313)/I(408) manifested transformation of amorphous to crystalline MoS2 phase. From the XPS observation, these findings seem to be ascribed to the formation of molybdenum disulphide by reaction of elemental sulphur in the oxygen vacancy sites formed throughout the decomposition of MoO2, as thermodynamically less stable, upon absorption of incoming photons energy.

Methods

Synthesis

Pure MoS2 nano-flowered species were synthesized as follows. At first, 15 mL of aqueous solution containing 15 mmol L−1 ammonium heptamolybdate, (NH4)6Mo7O24 4H2O, and 270 mmol L−1 thiourea was poured in a Teflon lined stainless steel autoclave in the volume of 25 mL. The synthesis was conducted at 225 °C for 15 h using 10 °C min−1 ramp. The synthesized products were collected by centrifugation, rinsed carefully with pure water and dried. To obtain the carpet of densely packed MoS2 nanoplatelets on the Ti substrate, the sample was inserted into a same but three times less concentrated solution and kept at optimized 225 °C for 5 h or 20 h using 10 °C min−1 ramp. The black coloured sample was carefully rinsed and dried naturally in the air.

Structure Characterization

For TEM sample preparation, a drop of the solution with the synthesized product was placed onto a 300 mesh copper grid covered with a carbon film. After removing an excess of the solution with an adsorbent paper, the sample was dried and investigated using a high-resolution transmission electron microscope HRTEM model FEI TECNAI F20 at an accelerating voltage of 120 keV. The morphology and elemental composition of the products obtained were investigated using a scanning electron microscope (FEI Quanta 200 F) and a Cross Beam Workstation Auriga equipped with a field emission gun and EDX spectrometer. The glancing angle XRD spectra were collected on a D8 diffractometer (Bruker AXS, Germany), equipped with a Göbel mirror as a primary beam monochromator for CuKα radiation.

X-ray photo electron spectroscopy

XPS measurements were carried out using an ESCALAB MKII spectrometer equipped with a new XR4 twin anode. The non-monochromatised MgKα X-ray source was operated at hν = 1253.6 eV with 300 W power (20 mA/15 kV) and the pressure in the analysis chamber was lower than 5 × 10−7 Pa during spectral acquisition. The spectra were acquired with an electron analyser pass energy of 20 eV for narrow scans and resolution of 0.05 eV and with a pass energy of 100 eV for survey spectra. All spectra were recorded at a 90° take-off angle and calibrated using the C 1 s peak at 284.6 eV. The spectra calibration, processing, and fitting routines were done using the Avantage software (5.918) provided by Thermo VG Scientific. Core level peaks of Mo 3d, O 1 s, Pt 4 f and S 2p were analysed using a nonlinear Shirley-type background, and the calculation of the elemental composition was performed on the basis of Scofield’s relative sensitivity factors.

Laser-Induced Selective Phase Transition Procedure (LISPTP)

The LISPTP procedure was performed in order to investigate the influence of a green (λ = 532 nm) nanosecond laser irradiation on the structural and compositional transformations of the films composed of MoS2-based nanoplatelets. Experimental setup (Fig. 8) consisted of the nanosecond laser Baltic HP (irradiation wavelength – 532 nm, pulse duration - 10 ns, pulse repetition rate - 100 kHz) beam expander and galvoscanner with an f -theta lens focusing objective (focal distance of 80 mm for 532 nm). Areas of 1 × 1 mm2 were scanned in the line stacks patterns with the laser beam. Distances between adjacent lines and scanning speed (100–500 mm/s) were adjusted to ensure the same pulse overlap in both directions. The distance between adjacent laser pulses d - was varied between 1 and 5 μm. The beam diameter measured on stainless steel according to described methodology38 at the focus was 22 μm. The irradiation dose was evaluated by multiplying laser fluence by a number of pulses per focused beam spot. The irradiation dose was varied between 0.05 to 12.74 J cm−2.

Raman

The 532-nm excited Raman spectra were recorded using inVia (Renishaw) spectrometer equipped with thermoelectrically cooled (−70 °C) CCD camera, 1800 lines/mm grating, and a microscope. The 532 nm beam of the CW solid state laser was used as an excitation source. Position of Raman spectra bands on the wavenumber axis was calibrated by the silicon peak at 520.7 nm. The 50x/0.75 NA objective was used during the measurements. The beam was focused to a 2 μm diameter spot size on the sample surface. The integration time was 100 s. Spectra are not smoothed. Parameters of the bands were estimated by fitting the experimental spectra with Gaussian-Lorentzian shape components using GRAMS/A1 8.0 (Thermo Scientific) software.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Jagminas, A. et al. Laser Light Induced Transformation of Molybdenum Disulphide-Based Nanoplatelet Arrays. Sci. Rep. 6, 37514; doi: 10.1038/srep37514 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Radislavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J. & Kis, A. Single-Layer MoS2 Transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis. A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and Optoelectronics of Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Mak, K. F., Lee, J., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically Thin MoS2: A New Direct-Gap Semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Splendiani, A. et al. Emerging Photoluminescence in Monolayer MoS2 . Nano Lett. 10, 1271–1275 (2010).

Ye, M., Winslow, D., Zhang, D., Pandey, R. & Yap, Y. K. Recent Advancement on the Optical Properties of Two-Dimensional Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2) Thin Films. Photonics 2, 288–307 (2015).

Chhowalla, M. et al. The Chemistry of Two-Dimensional Layered Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 5, 263–275 (2013).

Yan, Y., Xia, B. Y., Hu, Z. & Wang, X. Recent Development of Molybdenum Sulphides as Advanced Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Catal. 4, 1693–1705 (2014).

Jaramillo, T. F. et al. Identification of Active Edge Sites for Electrochemical H2 Evolution from MoS2 Nanocatalysts. Science 317, 100–102 (2007).

Xie, J. et al. Defect-Rich MoS2 Ultrathin Nanosheets with Additional Active Edge Sites for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Mater. 25, 5807–5813 (2013).

Chang, Y.-H. et al. Highly Efficient Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Production by MoSx Grown on Graphene-Protected 3D Ni Foams. Adv. Mater. 25, 756–760 (2013).

Lauersen, A. B., Vesborg, P. C. K. & Chorkendorff, I. A high-porosity carbon molybdenum sulphide composite with enhanced electrochemical hydrogen evolution and stability. Chem. Commun. 49, 4965–4967 (2013).

Mocatta, D. et al. Heavily Doped Semiconductor Nanocrystal Quantum Dots. Science 332, 77–81 (2011).

Wu, C. et al. Hydrogen-Incorporation Stabilization of Metallic VO2(R) Phase to Room Temperature, Displaying Promising Low-Temperature Thermoelectric Effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13798–13801 (2011).

Xie, J. et al. Controllable disorder engineering in oxygen-incorporated MoS2 ultrathin nanosheets for efficient hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 17881–17888 (2013).

Liu, Y.-R. et al. Facile synthesis of one-dimensional MoOx-based nanostructure for electrolytic hydrogen evolution. ECS Electrochem. Lett. 4, H5–H9 (2015).

Late, D. J., Liu, B., Matte, H. S. S. R., Dravid, V. P. & Rao, C. N. R. Hysteresis in Single-Layer MoS2 Field Effect Transistors. ACS Nano 6, 5635–5641 (2012).

Wypych, F. & Schöllhorn, R. 1T-MoS2, a new metallic modification of molybdenum disulphide. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1386–1388 (1992).

Huang, X., Zeng, Z. & Zhang, H. Metal dichalcogenide nanosheets: preparation, properties and application. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 1934–1948 (2013).

Helveg, S. et al. Atomic-Scale Structure of Single-Layer MoS2 Nanoclusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 951–954 (2000).

Lauritsen, J. V. et al. Atomic-scale insight into structure and morphology changes of MoS2 nanoclusters in hydrotreating catalysts. J. Catal. 221, 510–522 (2004).

Benck, J. D., Chen, Z., Kuritzky, L. Y., Forman, A. J. & Jaramillo, T. F. Amorphous Molybdenum Sulfide Catalysts for Electrochemical Hydrogen Production: Insights into the Origin of their Catalytic Activity. ACS Catal. 2, 1916–1923 (2012).

Liu, K.-K. et al. Growth of Large-Area and Highly Crystalline MoS2 Thin Layers on Insulating Substrates. Nano Lett. 12, 1538–1544 (2012).

Wang, H. W., Skeldon, P., Thompson, G. E. & Wood, G. C. Synthesis and Characterization of Molybdenum Disulphide Formed from Ammonium Tetrathiomolybdate. J. Mater. Sci. 32, 497–502 (1997).

Li, W. J. et al. Hydrothermal synthesis of MoS2 Nanowires. J. Cryst. Growth 250, 418–422 (2003).

Zhou, W. J. et al. Synthesis of Few-Layer MoS2 Nanosheet-Coated TiO2 Nanobelt Heterostructures for Enhanced Photocatalytic Activities. Small 9, 140–147 (2013).

Zhang, H., Liu, H., Zheng, Y., Hu, Y. & MacLennan, A. Understanding of the Effect of Synthesis Temperature on the Crystalization and Activity of Nanbo-MoS2 Catalyst. Appl. Catal. B. Environm. 165, 537–546 (2015).

Parzinger, E. et al. Photocatalytic Stability of Single- and Few-Layer MoS2 . ACS Nano 9, 11302–11309 (2015).

Yan, Y., Ge, X. M., Liu, Z. L., Lee, J. M. & Wang, X. Facile synthesis of low crystalline MoS2 nanosheet-coated CNTs for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanoscale 5, 7768–7771 (2013).

Rao, C. N. R., Maitra, U. & Waghmare, U. V. Extraordinary attributes of 2-dimensional MoS2 nanosheets, Chem. Phys. Lett. 609, 172–183 (2014).

Late, D. J., Lin B., Matte, H. S. S. R., Rao, C. N. R. & Dravid, V. P. Rapid Characterization of Ultrathin Layers of Chalcogenides on SiO2/Si Substrates. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 1894–1905 (2012).

Lv, R. et al. Transition metal dichalcogenides and beyond: Synthesis, properties, and applications of single- and few-layer nanosheets. ACS Chem. Res. 48, 56–64 (2015).

Hu, T., Li, R. & Dong, J. A new (2x1) dimerized structure of monolayer 1T-molybdenum disulfide, studied from first principles calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 174702 (2013).

Seguin, L., Figlarz, M., Cavagnat, R. & Lassegues, J.-C. Infrared and Raman spectra of MoO3 molybdenum trioxides and MoO3 xH2O molybdenum trioxide hydrates. Spectrochim. Acta A 51, 1323–1344 (1995).

Ou, J. Z., Campbell, J. L., Yao, D., Wlodarski, W. & Kalantar-Zadeh, K. In situ Raman spectroscopy of H2 gas interaction with layered MoO3, J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 10757–10763 (2011).

Wang, T., Li, J. & Zhao, G. Synthesis of MoS2 and MoO3 hierarchical nanostructures using a single-source molecular precursor, Powder Technol. 253, 347–351 (2014).

Wagner, C. D., Naumkin, A. V., Kraut-Vass, J. W., Allison, C. J., Powell, J. R. & Rumble, J. NIST Standard Reference Database 20, Version 3.4 http://srdata.nist.gov/xps/Default.aspx (2003).

Moulder, J. F., Chastain, J. & King, R. C. Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. A Reference Book of Standard Spectra for Identification and Interpretation of XPS Data, Physical Electronics, Eden Prine, MN, (1995).

Bauerle, D. Laser Processing and Chemistry 3rd edition, Springer, (2000).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the help of Dr. V. Pakštas for the collection of XRD patterns and Arnas Naujokaitis for SEM observations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J. and G.N. guided the research and prepared manuscript. G.R. and R.T. co-designed the laser light experiments. R.Ž. fabricated nanoplatelet MoS2 films. V.J. conducted the XPS measurements. All of the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Jagminas, A., Niaura, G., Žalnėravičius, R. et al. Laser Light Induced Transformation of Molybdenum Disulphide-Based Nanoplatelet Arrays. Sci Rep 6, 37514 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37514

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37514

This article is cited by

-

Oxygen reduction reaction kinetics of 2H-MoS2 and mixed-phase 1T/2H-MoS2 as a metal-free cathodic catalyst for PEM fuel cells

Journal of Applied Electrochemistry (2024)

-

Synthetic 3D flower-like 1T/2H MoS2@CoFe2O4 composites with enhanced microwave absorption performances

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

-

Raman spectral studies on phonon softening, surface temperature, fano resonance, and phase change in MoS2 nanoflakes

Applied Physics A (2023)

-

MoS2 with Organic Fragment - a New Hybrid Material for Laser Writing

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Exfoliation of Transition Metal Dichalcogenides by a High-Power Femtosecond Laser

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.