Abstract

RSM is a powerful tool for optimizing photocatalytic processes. The BWO-GO photocatalysts have been successfully synthesized via inorganic-salt-assisted hydrothermal method. XRD, TEM, FESEM, HRTEM and STEM are used to characterize BWO-GO heterojunction. UV-vis, PL, ESR and radical scavenger experiments are used to explore the photocatalysis mechanism. The photocatalysts are evaluated by TC photodegradation under visible light irradiation. And the main active species in TC photodegradation is ·O2−. Response surface methodology is used to optimize three key independent operating parameters, namely photocatalyst dosage (X1), percentages of GO (X2) and reaction time (X3), for TC photodegradation. The central composite design (CCD) is used to conduct experiments. The results showed that TC removal is significantly affected by the synergistic effect of linear term of X1 and X3. However, the quadratic terms of X12 and X32 had an antagonistic effect on T removal. The obtained RSM model (R2 = 0.9206) shows a satisfactory correlation between experimental and predicted values of TC removal. The optimized conditions is of 0.3 g photocatalyst dosage, 1.49 wt% GO loaded percentage and 90 min reaction time. Under this condition, theoretical prediction removal is 80.22% and the actual removal is 78.43%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tetracycline (TC) is one of the most used antibiotic chemicals, which used in human and veterinary medicine. Traditionally, it was not regarded as environmental pollutants; however, its occurrence in aquatic systems has attracted more and more attention as biological impacts and potential risks to the environment, as well as to human health, have been reported1,2,3,4. Recently, photocatalytic TC degradation has attracted more and more concentration, as the photocatalysis technology is economic, environmental and nontoxic and owns considerable application. Various photocatalysts have been developed and applied into TC degradation, such as TiO25, V2O56, NaNbO37 and g-C3N48.

Recently, much attention has been given to a series of visible light active bismuth-based photocatalysts. Many Bi3+- and Bi5+-containing compounds have been found to possess a narrow band gap and exhibit visible light photocatalytic activity because of the hybridized O2p and Bi6s2 valence bands9,10,11,12, such as Bi2MoO613, BiOI14, Bi2WO615, Bi2O2CO316. However, all these Bi-based photocatalysts don’t show great photocatalytic performance. In the Bi-based photocatalysts, there is a special one-Bi3.84W0.16O6.24 (BWO). It owns nonintegral atomic ratio and its formation is attributed to the different solubility of WO42− and (Bi2O2)2+ in precursor suspensions with various pH17. Though BWO is a promising photocatalyst in environmental application and owns great optimized prospect. In our previous work, the pure BWO octahedral-like nanostructures could been obtained via a simple, quick and eco-friendly microwave-assisted synthetic method18. They exhibited the very highly photocatalytic activities for the tetracycline degradation under visible light irradiation. GO, potential as a reaction platform (large specific surface area and outstanding electronic properties), particularly for catalysis, has also been broadly described in numerous reports19,20,21. GO can be regarded as graphene functionalized by carboxylic acid, hydroxyl and epoxide groups22,23,24. And it is favorable for tunable optical, conductive and chemical properties25,26. Though, GO has been widely used in photocatalysis for contaminant removal, such as GO/TiO227,28, GO/ZnO29, GO/Ag30, GO/N-TiO231 and so on. To our best knowledge, there are no reports about Bi3.84W0.16O6.24-GO (BWO-GO) and it’s a good candidate for contaminant removal.

Nowadays, the efforts in photocatalysis are almost in changing material properties to improve the photocatalytic activity. And few efforts in optimizing the photocatalytic conditions to improve the photocatalytic activity. The RSM has been proved to be a powerful statistical technique for obtaining optimum conditions for advanced oxidation processes and evaluating the interactions of mutually influencing parameters with a limited number of experiments32,33,34. Compared to the classical approach for the same number of estimated parameters, RSM cannot only evaluate the interactions effects among tested operating variables but also reduce the number of experiments to be undertaken35,36,37. In this article, for the first time, a BWO-GO composite photocatalyst is synthesized and its photocatalytic activity is studied. In the photoactivity evaluation via the photocatalytic degradation of TC under visible-light irradiation. The parameters varied are the photocatalyst concentration, loaded percentages of GO and reaction time. Three factor central composite design (CCD) combined with RSM is applied to optimize the response as the photodegradation percentage of TC using BWO-GO (photocatalyst concentration, percentages of GO and reaction time is varied during the degradation).

Results and Discussion

Characterization of BWO-GO

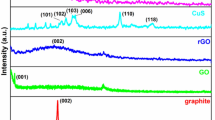

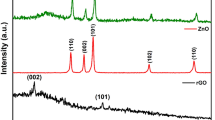

The XRD patterns of GO, BWO and BWO-GO nanocomposites are shown in Fig.1. The peaks in BWO could be readily indexed as JCPDS No. 00–043–0047. The lattice constants of BWO are a = 5.57 Å, b = 5.57 Å, and c = 5.56 Å. The characteristic peaks are sharp, implying the obtained nanostructures are well-crystallized. The XRD pattern of BWO-GO shows similar peak to pure BWO. Notably, no characteristics peaks of graphene or GO are observed in the composites. This is possibly due to two reasons: destruction of the regular stacking of GO due to microwave hydrothermal conditions38 and at relatively low graphene oxide loading in the nanocomposites, covering up of peaks of GO by the diffraction signals of BWO39.

The morphology and size of the products prepared by the procedure described in the experimental section are visualized by FESEM, HRTEM and STEM, as shown in Figs 2 and 3. As shown in low magnification (Fig. 2a), the FESEM results clearly indicate that the main component of the as-obtained BWO particle of about 200 nm, is uniform octahedral structure. As shown in TEM images (Fig. 2b), the BWO nanoparticles are deposited onto the graphene oxide sheets. This is due to the interaction between the hydrophilic functional groups of GO and BWO40.

To further investigate the micro-morphology and structure, HRTEM and STEM is employed. Figure 3 shows the STEM and HRTEM images of BWO-GO. In the mapping of W (Fig. 3b), O (Fig. 3c), Bi (Fig. 3d), C (Fig. 3e), it can be seen the homogeneous distribution of elements within the selected area. From analysis of high-resolution images as shown in Fig. 3f, the edge area of the octahedral nanoparticles exhibits well-resolved 2D lattice fringes. And it is possible to measure the lattice fringe spacing as being 3.19 Å, corresponding to the (111) planes of BWO.

To check the elemental composition of the BWO-GO composite, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed. Figure 4(a) shows the full XPS spectrum of BWO-GO, W, Bi, O and C elements. As shown in Fig. 4(b), the binding energies of 34.7 and 36.97 eV for W 4f5/2 peaks are attributed to W6+ in Bi3.84W0.16O6.2441. As displayed in Fig. 4(c), the characteristic binding energy values of 158.69 and 164.02 eV for Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2 reveal a trivalent oxidation state for bismuth in Bi3.84W0.16O6.2442. The O 1 s binding energy 529.68 eV (crystal lattice oxygen) and C 1 s binding energies 284.4 eV in GO are also identified in the spectra (Fig. 4(d) and (e)). These results show evidence for the presence of GO in the ternary heterostructured BWO-GO composite.

As the loaded percentage of GO very low, the GO vibration signals are very low. The FTIR spectrum in Fig. 5 displays vibration modes which corresponds to O=C-O (1330 cm−1), C-O-C (1236 cm−1), sp2 hybridized C=C (1610 cm−1), ketonic species C=O (1820 cm−1), carboxyl COOH (1722 cm−1) and hydroxyl (water) (1048 cm−1). The spectrum indicates the prepared graphite oxide consists of both hydrophobic (C=C) and hydrophilic (C-C, C-OH, COOH) species which makes GO amphiphilic43,44.

Optical absorbance spectrum of a semiconductor is affected by its electronic structure feature and then determines the photocatalytic activity. As is shown in Fig. 6(a), the absorption shoulder of precipitation of the precursor is found at ca. 440 nm. And a blue-shift of the optical absorption edge is observed from the UV-Vis transmission spectra, while the GO is loaded. The UV-vis spectra of the synthesis products show important features: the high absorption of the GO-loaded products in the visible range of the optical spectrum, in comparison to the previously observed GO-free nanostructured BWO.

To investigate the structural properties of the BWO-GO composites and electronic coupling between GO and BWO, we have employed Raman spectroscopy that has been established as a powerful method for the characterization of carbon nanomaterials45. Figure 6(b) displays the Raman spectra of the BWO-GO composites compared with the bare GO suspension and BWO at 532 nm excitations. The pristine GO exhibits the graphitic Raman G band at 1580 cm−1 arising from the bond stretching of sp2 carbon atoms and the defect activated D band at 1350 cm−1. The Raman spectra of BWO-GO shows that the two bands have similar intensity (ID/IG = 1.06) this implies a high quantity of structural defects due to the oxidation of graphite46. The pristine BWO exhibits two absorption peaks at 850 cm−1 and 325 cm−1. Above absorption peaks all exist in the spectra of BWO-GO composites. The clear identification of the BWO-GO heterojunction is allowed by the Raman spectroscopy.

Photocatalytic activity test

The photocatalytic activities are tested by TC removal and TC mineralization. Figure 7 displays TC removal and mineralization by 2 wt% BWO-GO in 60 min. As is shown in Fig. 7(a), the obviously improved TC removal comes from the synergistic effect of BWO and GO. Uniformly, the obviously improved TC mineralization also comes from the synergistic effect of BWO and GO (Fig. 7b).

Response surface methodology model analysis

The CCD design combined with the experimental and predicted data of TC photocatalytic degradation under visible light irradiation using BWO-GO nanocomposites are listed in Table 1. A second-order polynomial expression shown in Eq. (1) consisting of 10 coefficients was attained from the analysis of variance (ANOVA) at 95% confidence level (p < 0.05).

where y refers to removal efficiency expressed in % and x1, x2, and x3 represent the uncoded values of photocatalyst concentration, percentages of GO and reaction time, respectively.

The sum of squares, mean squares, estimated coefficient, standard error, and the corresponding F-value and p-values are also tested using ANOVA, and the results are summarized in Table 2. In statistics, a model with a large F-value (Fmodel = 23.46, much greater than unity) and a small p-value (<0.05) is considered to be significant. Furthermore, the fit of the model is verified by the coefficient of determination R2. In this study, the value of the determination coefficient (R2 = 0.9679) shown in Table 2 indicated that 96.79% of the variability in the response could be explained by the model. Also, the adjusted determination coefficient R2 = 0.9266 is also high indicating that the obtained model is significant.

It is observed in the ANOVA test that for the first-order main effects, x1 and x3 are more highly significant than x2. In contrast, for the second-order main effects, x22 is more highly significant than x12 and x32. Moreover, in terms of interactive effects, x2 x3 is more significant than x1 x2 and x1 x3.

The ANOVA reveals that Eq. (1) (R2 = 0.9679) suitably explains the actual relationship between the response and the variables, which can be seen in Fig. 8(a) by comparing the experimentally measured values against the predicted responses for the TC removal efficiency. Moreover, the normal probability plot of the residuals is illustrated in Fig. 8(b), and it shows that there is almost no violation of the assumptions: errors are normally distributed and independent, while the error variance is homogeneous.

After performing all the experiments which are suggested by CCD, the response surface analysis is carried out, in order to investigate of effects of the variables and find optimal conditions for E. coli disinfection. Response surface analysis helps in identification of the type of interactions between the selected variables. In Fig. 9, response surface plots of TC concentration are displayed for the three pairs of the factors. According to the Fig. 8(a) and (b), the TC removal efficiency steadily improved with the increased photocatalyst dosage of the photocatalyst dosage from 0.1 to 0.3 g. The main reason is that the number of active sites in the solution increased with catalyst dosage. Furthermore, as it can be concluded from these figures, TC removal is extremely more sensitive to changes in catalyst dosage compared with other parameters. This is in agreement with the P-values obtained for each parameter from ANOVA.

According to the Fig. 9(b) and (c), the TC removal efficiency improved with the increased reaction time of the reaction time from 30 to 90 min. Furthermore, according to P-values obtained from ANOVA, TC removal is slightly sensitive to changes in reaction time from 30 to 90 min.

According to the Fig. 9(b) and (c), the TC removal doesn’t have linear relationship with GO percentages, and the optimized GO percentage is of 1.49 wt%. The proper explanation can be that 1.49 wt% is the best percentage for photoinduced hole-electron separation between GO and BWO.

The optimal values of the selected variables are obtained using numerical optimization method provided by the Design-Expert 9.0.3 software. The goal of the optimization is to minimize the final concentration of TC in the solution. The point at which the final concentration of TC is predicted to be in its lowest value is found to be 0.3 g, 1.49 wt%, and 90 min for photocatalyst dosage, GO percentage and reaction time, respectively. Based on the suggested model (Equation (1)), final TC removal under the optimal condition should be 80.22%. To confirm the accuracy of the optimization, duplicate verification experiments are carried out. The average final TC removal in these experiments is found to be 78.43%, which is reasonably close to the predicted value. Therefore, the optimum point determined by RSM is successfully verified and suggests that RSM can be a powerful tool for optimizing photocatalytic purification processes.

Mechanism of photocatalysis

For the better application of BWO-GO photocatalyst in pollutants photocatalytic degradation, it is imperative to understand the mechanism of photocatalysis of TC under visible light irradiation. To explore the mechanism of photocatalytic degradation of TC by BWO-GO heterostructure photocatalysts, ESR spectrum and radical scavenger experiments are employed to ascertain the active species. ESR spectrums are used for the detection of the production of OH· and ·O2−. Benzoquinone (BQ) as a scavenger for ·O2−, EDTA for h+ and tertiary butanol (TBA) for OH· are employed to observe the direct influence on the degradation rates of each radicals. The addition of quenchers to the TC solution are all prior to the addition of photocatalysts. As a consequence of capture, photocatalytic degradation of TC will be influenced and photocatalytic efficiency is changed. The effects of a series of scavengers on the photodegradation efficiency are shown in Fig. 10. As is shown in Fig. 10(a), the degradation efficiency of TC decreases rapidly from 79.04% to 13.43% after the addition of BQ, indicating that ·O2− is the main active species in the photodegradation process. While TBA is added, the photodegradation efficiency of TC decrease from 79.04% to 77.65%. It is indicated that ·OH is not main active species. However, while the EDTA is adding, the degradation efficiency increases a little from 79.04% to 81.54%. It may be due to the quenching of h+, which promotes the separation of photoinduced holes and electrons. Then the degradation efficiency is improved. The ESR spectra also reveals the proof of these phenomenon, as is shown in Fig. 10(b). In these ESR detection, 10 mg samples and 50 μL DMPO are dissolved in 0.5 mL deionized water and stirred for 10 min, which is used in the detection of hydroxyl radicals (DMPO-·OH). 10 mg samples and 50 μL DMPO are dissolved in 0.5 mL CH3OH and stirred for 10 min, which is used in the detection of superoxide radicals (DMPO-·O2−). Before the irradiation, there are no characteristic peak of ·OH and ·O2−. After the irradiation (60 s), the characteristic peak intensity of ·O2− is much larger than that of OH·. It is also accord with the consequence of radical scavenger experiments, that the ·O2− is the main active species.

Combining the ESR spectrum and radical scavenger experiments, a possible electron transfer behavior is proposed (Fig.11(a)). According to our previous work, the CB and VB of BWO is +0.36 and +3.26 eV, separately47. In the photocatalytic process, electron-hole pairs are formed when BWO is irradiated by visible light, and electrons at the VB are excited to the CB, inducing the separation with holes in the VB. The existence of GO in the composite promoted the photocatalytic activity and stability. First, the high surface area of GO provides more active adsorption sites and photocatalytic reaction sites, which has the benefit of improving the photocatalytic activity. Second, GO acts as an effective acceptor of the photoexcited electrons, making ·O2− radicals produced by the reduction of O2 molecules adsorbed on catalyst surface48.

In order to prove above-proposed mechanism, electron-hole pairs’ recombination for BWO and BWO-GO is detected by photoluminescence (PL) technique. PL is an effective approach for obtaining information about the migration and separation efficiency of the photo-generated charge carriers. The room temperature PL emission spectra of BWO and BWO-GO nanocomposites with the excitation wavelength of 320 nm are compared and illustrated in Fig. 11(b). The photoluminescence spectra are recorded over the wavelength range 420–520 nm; both samples exhibited the usual band-edge emission with a peak at 470 nm, the strongest emitting peaks around 470 nm can be attributed to the intrinsic luminescence of BWO. The peaks centered at 449, 481 and 492 nm can be attributed to the intrinsic transition of Bi3+, defects of metal atoms and oxygen vacancies during the crystal growing process49,50, which is become defect centers and thus affects the optical properties of BWO. It can be seen from the photoluminescence spectra that there is a significant decrease in intensity in the PL spectrum of the BWO-GO composite photocatalyst. The weaker PL intensity, the bigger possibility of photoexcited charge carrier separation51. Consequently, a lower PL emission intensity of the BWO-GO nano-octahedron suggests that GO can easily capture the photoexcited electrons from BWO-GO and promote the interfacial charge transfer, resulting in a lower recombination rate of the e−-h+ pairs.

Conclusion

The BWO-GO photocatalysts have been successfully synthesized by a facile inorganic salt-assisted hydrothermal method. The octahedral BWO nanoparticles have been successfully anchored on the GO sheet. The BWO-GO heterojunction is in favor of photocatalytic activity enhancement and the main active species in TC photodegradation is ·O2−.

The optimization and the modeling of photocatalytic degradation of TC are evaluated by using a central composite design. The second order polynomials are useful in determining the optimum parameters for TC removal. The obtained optimum condition for TC removal is to achieve 80.22% with 0.3 g photocatalyst dosage, 1.49% GO loaded percentage and 90 min reaction time. This study will provide new insights for application of GO sensitized BWO photocatalytic nanocomposites for micropollutants removal from drinking water.

Materials and Methods

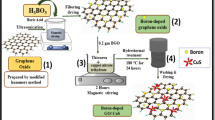

Synthesis of BWO-GO

GO was synthesized by the modified Hummers’ method and the detailed procedures could be found elsewhere52. In addition, a mixture of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O (1.0 mmol), GO and Na2WO4·2H2O (0.5 mmol) was dissolved in 50 mL of deionized water, followed by the addition of 2 ml of ethylenediamine (En, 99%). After being stirred for 30 min, the mixture was transferred into a 250 mL roundbottom flask in a microwave system (XH-300UL, Beijing Xiang Hu Technology Development Co. Ltd) equipped with in-situ magnetic stirring. After treating the mixture at 100 °C for 5 min under microwave radiation, the final products were collected using centrifugation, washed several times with deionized water and ethanol, and dried in air at 60 °C for 12 h.

Characterization

The crystal structures of the samples are determined with the X-ray diffraction (XRD) method using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images are collected on an S-4800 field emission scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) images are collected on an F20STWIN electron microscope (Tecnai G2, FEI Co.), using a 200 kV accelerating voltage. UV-vis diffused reflectance spectra of the samples are obtained with a UV-vis spectrophotometer (UV2550, Shimadzu, Japan); BaSO4 is used as the reflectance standard. The photoluminescence properties of the obtained samples are measured on a Perkin-Elmer LS 55 luminescence spectrometer, at room temperature. ESR analysis is conducted with a Bruker EPR A300-10/12 spectrometer.

Photocatalytic degradation of TC

The photodegradation reaction for TC is carried out under simulated sunlight irradiation using a 150 W Xe lamp with a cut off filter (λ ≥ 400 nm) in a photochemical reactor under visible light. The initial TC concentration is 10 mg/L. 0.10 g of the photocatalyst is put into 100 mL of a TC solution. Before the photodegradation experiment is initiated, the suspension is magnetically stirred in the dark for 30 min to reach the absorption equilibrium. The sampling analysis is conducted in 10 min intervals. The photocatalytic degradation ratio (DR) is calculated using the following formula:

where C0 is the initial absorbance of TC at the absorption equilibrium, while Ci is the absorbance after the sampling analysis. The absorbance of TC is measured using a UV-vis spectrophotometer with the maximum absorption wavelength at 357 nm.

Central composite design (CCD)

The central composite design (CCD) is applied to investigate the effects of the three independent variables on the response functions. The independent variables are photocatalyst concentration (X1), percentages of GO (X2) and reaction time (X3). The levels of the three major factors identified are summarized in Table 3. The notations (−1) and (+1) refer to the low level and the high level of the two-level-factorial design, respectively. In developing the regression equation developed by Box-Hunter, the test factors are coded according to the following equation:

where Xi is the dimensionless value of an independent variable, xi represents the real value of the independent variable, x0 is the real value of the independent variable at the center point, and Δxi is the step change53.

where Y is the predicted response, b0 and the offset term, bi the linear effect, bij the squared effect and bii is the interaction effect.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Song, C. et al. Fabrication, Characterization and Response Surface Method (RSM) Optimization for Tetracycline Photodegration by Bi3.84W0.16O6.24- graphene oxide (BWO-GO). Sci. Rep. 6, 37466; doi: 10.1038/srep37466 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Boxall, A. B. A., Kolpin, D. W., Halling-Sorensen, B. & Tolls, J. Are veterinary medicines causing environmental risks? Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 286A–294A (2003).

Fares, M., Abedi-Valugerdi, M., Hassan, M. & Potacova, Z. DNA damage, lysosomal degradation and Bcl-xL deamidation in doxycycline- and minocycline-induced cell death in the K562 leukemic cell line. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 463, 268–274 (2015).

Yang, X., Flowers, R. C., Weinberg, H. S. & Singer, P. C. Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in an advanced wastewater reclamation plant. Water Res. 45, 5218–5228 (2011).

Du, E. D., Cao, P. R., Sun, Y., Gao, N. Y. & Wang, L. P. Application Of Fluorescence Excitation-Emission Matrices And Parafac Analysis For Indicating The Organic Matter Removal From Micro-Polluted Raw Water In Water Treatment Plant. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 21, 4030–4039 (2012).

Liu, Y. B. et al. Photoelectrocatalytic degradation of tetracycline by highly effective TiO2 nanopore arrays electrode. J. Hazard. Mater. 171, 678–683 (2009).

Hong, Y. Z. et al. In-situ synthesis of direct solid-state Z-scheme V2O5/g-C3N4 heterojunctions with enhanced visible light efficiency in photocatalytic degradation of pollutants. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 180, 663–673 (2016).

Song, C. J. et al. Synthesis of a g-C3N4-sensitized and NaNbO3-substrated II-type heterojunction with enhanced photocatalytic degradation activity. Crystengcomm 17, 4575–4583 (2015).

Hong, Y. Z. et al. Efficient and stable Nb2O5 modified g-C3N4 photocatalyst for removal of antibiotic pollutant. Chem. Eng. J. 299, 74–84 (2016).

Ke, D. N., Peng, T. Y., Ma, L., Cai, P. & Jiang, P. Photocatalytic water splitting for O-2 production under visible-light irradiation on BiVO4 nanoparticles in different sacrificial reagent solutions. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 350, 111–117 (2008).

Li, E. J., Chen, L., Zhang, Q. A., Li, W. H. & Yin, S. F. Bismuth-Containing Semiconductor Photocatalysts. Prog. Chem. 22, 2282–2289 (2010).

Zhang, Z. J., Wang, W. Z., Shang, M. & Yin, W. Z. Low-temperature combustion synthesis of Bi2WO6 nanoparticles as a visible-light-driven photocatalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 177, 1013–1018 (2010).

Jiang, L., Wang, L. Z. & Zhang, J. L. A direct route for the synthesis of nanometer-sized Bi2WO6 particles loaded on a spherical MCM-48 mesoporous molecular sieve. Chem. Commun. 46, 8067–8069 (2010).

Li, X. X. et al. Synthesis of flower-like Ag/AgCl-Bi2MoO6 plasmonic photocatalysts with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 176, 62–69 (2015).

Park, Y., Na, Y., Pradhan, D., Min, B. K. & Sohn, Y. Adsorption and UV/Visible photocatalytic performance of BiOI for methyl orange, Rhodamine B and methylene blue: Ag and Ti-loading effects. Crystengcomm 16, 3155–3167 (2014).

Wang, H. L. et al. Surface decoration of Bi2WO6 superstructures with Bi2O3 nanoparticles: an efficient method to improve visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity. Crystengcomm 15, 9011–9019 (2013).

Hu, R. P., Xiao, X., Tu, S. H., Zuo, X. X. & Nan, J. M. Synthesis of flower-like heterostructured beta-Bi2O3/Bi2O2CO3 microspheres using Bi2O2CO3 self-sacrifice precursor and its visible-light-induced photocatalytic degradation of o-phenylphenol. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 163, 510–519 (2015).

Yao, S. et al. Morphology modulated growth of bismuth tungsten oxide nanocrystals. J. Solid State Chem. 182, 236–239 (2009).

Li, X. Y. et al. Morphological evolution and visible light driven degradation of tetracycline by Bi3.84W0.16O6.24 nanostructures. RSC Advances 5, 66940–66946 (2015).

Jiang, Y., Wang, W.-N., Biswas, P. & Fortner, J. D. Facile Aerosol Synthesis and Characterization of Ternary Crumpled Graphene-TiO2-Magnetite Nanocomposites for Advanced Water Treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 11766–11774 (2014).

Zhang, H., Lv, X., Li, Y., Wang, Y. & Li, J. P25-Graphene Composite as a High Performance Photocatalyst. ACS Nano 4, 380–386 (2010).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. A roadmap for graphene. Nature 490, 192–200 (2012).

Lim, S. P., Pandikumar, A., Huang, N. M. & Lim, H. N. Reduced graphene oxide-titania nanocomposite-modified photoanode for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Int. J. Energy Res. 39, 812–824 (2015).

Peik-See, T., Pandikumar, A., Ngee, L. H., Ming, H. N. & Hua, C. C. Magnetically separable reduced graphene oxide/iron oxide nanocomposite materials for environmental remediation. Catal. Sci. & Technol. 4, 4396–4405 (2014).

Jing, J., Zhang, Y., Li, W. & Yu, W. W. Visible light driven photodegradation of quinoline over TiO2/graphene oxide nanocomposites. J. Catal. 316, 174–181 (2014).

Gilje, S., Han, S., Wang, M., Wang, K. L. & Kaner, R. B. A chemical route to graphene for device applications. Nano Lett. 7, 3394–3398 (2007).

Boukhvalov, D. W. & Katsnelson, M. I. Modeling of graphite oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 10697–10701 (2008).

Jeong, H. J. et al. One-Step Transfer and Integration of Multifunctionality in CVD Graphene by TiO2/Graphene Oxide Hybrid Layer. Small 10, 2057–2066 (2014).

Chen, C. et al. Synthesis of Visible-Light Responsive Graphene Oxide/TiO2 Composites with p/n Heterojunction. ACS Nano 4, 6425–6432 (2010).

Zhang, Z. et al. Solution-processed anchoring zinc oxide quantum dots on covalently modified graphene oxide. J. Nanopart. Res. 16 (2014).

Huang, Q. et al. A facile and green method for synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/Ag hybrids as efficient surface enhanced Raman scattering platforms. J. Hazard. Mater. 283, 123–130 (2015).

Bhirud, A. P. et al. In-situ preparation of N-TiO2/graphene nanocomposite and its enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production by H2S splitting under solar light. Nanoscale 7, 5023–5034 (2015).

Arslan-Alaton, I., Ayten, N. & Olmez-Hanci, T. Photo-Fenton-like treatment of the commercially important H-acid: Process optimization by factorial design and effects of photocatalytic treatment on activated sludge inhibition. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 96, 208–217 (2010).

Olmez-Hanci, T., Arslan-Alaton, I. & Basar, G. Multivariate analysis of anionic, cationic and nonionic textile surfactant degradation with the H2O2/UV-C process by using the capabilities of response surface methodology. J. Hazard. Mater. 185, 193–203 (2011).

Hou, D., Goei, R., Wang, X., Wang, P. & Lim, T.-T. Preparation of carbon-sensitized and Fe-Er codoped TiO2 with response surface methodology for bisphenol A photocatalytic degradation under visible-light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 126, 121–133 (2012).

Zhang, Z. & Zheng, H. Optimization for decolorization of azo dye acid green 20 by ultrasound and H2O2 using response surface methodology. J. Hazard. Mater. 172, 1388–1393 (2009).

Karacan, F., Ozden, U. & Karacan, S. Optimization of manufacturing conditions for activated carbon from Turkish lignite by chemical activation using response surface methodology. Appl. Therm. Eng. 27, 1212–1218 (2007).

Du, E. D., Zhang, Y. X. & Zheng, L. Photocatalytic degradation of dimethyl phthalate in aqueous TiO2 suspension: a modified Langmuir-Hinshelwood model. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 97, 83–90 (2009).

Liu, J. et al. Self-Assembling TiO2 Nanorods on Large Graphene Oxide Sheets at a Two-Phase Interface and Their Anti-Recombination in Photocatalytic Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 4175–4181 (2010).

Xu, C. & Wang, X. Fabrication of Flexible Metal-Nanoparticte Film Using Graphene Oxide Sheets as Substrates. Small 5, 2212–2217 (2009).

Appavoo, I. A., Hu, J., Huang, Y., Li, S. F. Y. & Ong, S. L. Response surface modeling of Carbamazepine (CBZ) removal by Graphene-P25 nanocomposites/UVA process using central composite design. Water Res. 57, 270–279 (2014).

Zou, J. P. et al. Fabrication of novel heterostructured few layered WS2-Bi2WO6/Bi3.84W0.16O6.24 composites with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 179, 220–228 (2015).

Gopalakrishnan, D., Damien, D. & Shaijumon, M. M. MoS2 Quantum Dot-Interspersed Exfoliated MoS2 Nanosheets. ACS Nano 8, 5297–5303 (2014).

Chandra, V. et al. Water-Dispersible Magnetite-Reduced Graphene Oxide Composites for Arsenic Removal. ACS Nano 4, 3979–3986 (2010).

Chen, X. X. & Chen, B. L. Macroscopic and Spectroscopic Investigations of the Adsorption of Nitroaromatic Compounds on Graphene Oxide, Reduced Graphene Oxide, and Graphene Nanosheets. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 6181–6189 (2015).

Dresselhaus, M. S., Jorio, A., Hofmann, M., Dresselhaus, G. & Saito, R. Perspectives on Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene Raman Spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 10, 751–758 (2010).

Zhang, D. C. et al. Enhanced capacitance and rate capability of graphene/polypyrrole composite as electrode material for supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 196, 5990–5996 (2011).

Li, X. et al. Morphological evolution and visible light driven degradation of tetracycline by Bi3.84W0.16O6.24 nanostructures. RSC Advances 5, 66940–66946 (2015).

Chen, X.-j. et al. Synthesis and characterization of Ag3PO4 immobilized with graphene oxide (GO) for enhanced photocatalytic activity and stability over 2,4-dichlorophenol under visible light irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 292, 9–18 (2015).

Alfaro, S. O. & Martinez-de la Cruz, A. Synthesis, characterization and visible-light photocatalytic properties of Bi2WO6 and Bi2W2O9 obtained by co-precipitation method. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 383, 128–133 (2010).

Wang, D. J. et al. AgBr quantum dots decorated mesoporous Bi2WO6 architectures with enhanced photocatalytic activities for methylene blue. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 11716–11727 (2014).

Liang, Q., Shi, Y., Ma, W., Li, Z. & Yang, X. Enhanced photocatalytic activity and structural stability by hybridizing Ag3PO4 nanospheres with graphene oxide sheets. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 15657–15665 (2012).

Gao, P., Liu, J., Lee, S., Zhang, T. & Sun, D. D. High quality graphene oxide-CdS-Pt nanocomposites for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 2292–2298 (2012).

Li, H., Gong, Y., Huang, Q. & Zhang, H. Degradation of Orange II by UV-Assisted Advanced Fenton Process: Response Surface Approach, Degradation Pathway, and Biodegradability. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 15560–15567 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (2127611 6, 21477050, 21301076, 21303074, 21522603 and 21576121), the Chinese-German Cooperation Research Project (GZ1091), the Excellent Youth Foundation of Jiangsu Scientific Committee (BK20140011), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-13-0835), the Henry Fok Education Foundation (141068) and Six Talents Peak Project in Jiangsu Province (XCL-025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weidong Shi & Liping Wang contributed to design the study and experiments analysis. Xinying Li contributed to sample synthesis. Chengjie Song contributed to structure characterization and write manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Song, C., Li, X., Wang, L. et al. Fabrication, Characterization and Response Surface Method (RSM) Optimization for Tetracycline Photodegration by Bi3.84W0.16O6.24- graphene oxide (BWO-GO). Sci Rep 6, 37466 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37466

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37466

This article is cited by

-

Enhancing uric acid electrochemical detection with copper ion-activated mini protein mimicking uricase within ZIF-8: response surface methodology (RSM) optimization

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2024)

-

On the influence of hydrothermal treatment pH on the performance of Bi2WO6 as photocatalyst in the glycerol photoreforming

Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences (2022)

-

Response Surface Modeling and Optimization of Gelcast Fused Silica Micro Hybrid Ceramic Composites

Silicon (2020)

-

In situ hydrothermal fabrication of visible light-driven g-C3N4/SrTiO3 composite for photocatalytic degradation of TC

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2020)

-

Photocatalytic degradation of ketoconazole by Z-scheme Ag3PO4/graphene oxide: response surface modeling and optimization

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.